2001

Genesis Catches Solar Wind

The Sun, like all stars, is powered by a dynamic balance between the gravitational contraction of an enormous concentration of mass and the outward pressure of intense nuclear fusion reactions occurring in the deep interior. Radiation escapes from the Sun, providing heat and light to the planets, but highly energetic particles also emerge from the Sun’s photosphere (effectively, its “surface”) and chromosphere (atmosphere) and are spewed out at high speeds into interplanetary space. This stream of particles is called the solar wind.

In 1995 the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA teamed up to launch a satellite called the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), which was specifically designed to study the dynamic environment of the Sun, including the solar wind, using high-resolution ultraviolet images and spectroscopy. SOHO continues to provide spectacular time-lapse views of our dynamic star.

Solar astronomers’ discoveries about the solar wind from SOHO and other studies generated substantial interest in a dedicated space mission to try to collect some of these far-flung pieces of the Sun. Planetary scientists, too, are keenly interested in the Sun’s composition, as it represents about 99.9 percent of the mass of the solar system and is the starting composition from which the planets formed. This interest ultimately led to a NASA mission called Genesis, which was designed to collect and return samples of the solar wind. The mission was launched in 2001 on a looping orbit around one of Earth’s gravitational Lagrange Points (L1), where a specially designed sample-return canister was exposed to solar wind particles until early 2004.

Despite the 2004 crash of the canister in the Utah desert because of a failed reentry parachute, many of the Genesis samples survived intact and have been intensely studied by geochemists and solar astronomers. Particles from the three types of solar wind (fast, slow, and coronal mass ejections) were collected and analyzed, and the results are providing important new data—some of it surprising—about the Sun’s composition, helping to refine our understanding of processes at work inside the Sun and other stars.

SEE ALSO Birth of the Sun (c. 4.6 Billion BCE), Lagrange Points (1772), Eddington’s Mass-Luminosity Relation (1924), Nuclear Fusion (1939).

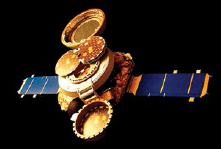

A giant coronal mass ejection from the Sun, photographed by the SOHO satellite in January 2002. Billions of tons of material are ejected by solar events such as this, creating a “solar wind” that interacts with the planets as it passes by. Samples of the solar wind were collected by the Genesis spacecraft (left).