2006

Demotion of Pluto

When Pluto was discovered in 1930, it was hailed as the solar system’s ninth planet, partially because it was estimated to be about the size of the Earth. Follow-up observations over the decades, and the discovery of Pluto’s moon Charon, eventually led to the realization that Pluto is a small world, only about 20 percent of the diameter and less than 1 percent of the mass of Earth. Still, with decades of inertia and countless textbooks touting Pluto as a cold and lonely outpost at the edge of the solar system, Pluto retained its status—and popularity—as a full-fledged planet.

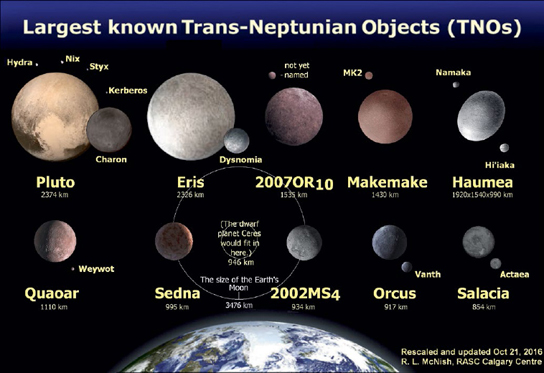

In the 1990s, however, it became clear that the solar system does not end at Pluto. In addition to the long-known population of long-period comets that likely originate from the Oort Cloud, more than a thousand Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) have now been discovered orbiting well past the orbit of Neptune, and the expectation is that many tens to hundreds of thousands yet remain to be discovered. Many of them are comparable in size to Pluto, or even larger.

If Pluto is a planet, then the potential proliferation of Pluto-size worlds would of course dramatically increase the number of planets in the solar system. This possibility caused consternation among some astronomers and compelled the world’s relevant governing agency, the International Astronomical Union (IAU), to reconsider the classification of Pluto-size worlds. In 2006 the IAU decided to formally “demote” Pluto and other large KBOs from planethood to a new class of object—dwarf planet—created to recognize the importance of this newly discovered class of small worlds but to distinguish them from the classical planets, which have significantly larger influences on their surroundings.

The demotion of Pluto caused significant public outcry, and even many astronomers and planetary scientists remain confused and deeply divided about the new formal definition of what it takes to be a planet. To many, any object that is large enough to have become roughly spherical under its own self-gravity, or that has had active internal processes that have differentiated it into core, mantle, and crust, could be considered a planet. And why not reclassify giant satellites such as Ganymede, Titan, and Europa (comparable to or larger than Mercury), as planets? Today, the debate continues to rage on about whether our solar system has 8 known planets, or perhaps 40 or more.

SEE ALSO Pluto and the Kuiper Belt (c. 4.5 Billion BCE), Discovery of Pluto (1930), Öpik-Oort Cloud (1932), Charon (1978), Kuiper Belt Objects (1992), Pluto Revealed! (2015).

Data (for the Pluto system) and artist’s renderings of the presently known largest small bodies in the Kuiper Belt, compared to the size of the Earth and the Moon. The largest asteroid, Ceres, is about the same size as 2002MS4.