1676

Speed of Light

Ole Christensen Røemer (1644–1710), Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695)

The nature of light has been debated throughout history. The Greek philosophers Aristotle, Euclid, and Ptolemy believed light was emitted from the eyes; because we see distant objects like stars instantly when we open our eyes, they believed that light must travel at an infinite speed. Eleventh-century scientists like the Muslim physicist al-Haytham and the Persian scholar al-Bīrūnī proposed that light had a finite speed, however, based on some early experiments in optics. The debate continued into the seventeenth century, with luminaries like Kepler favoring an infinite speed and Galileo favoring a finite speed. What was needed was a definitive measurement.

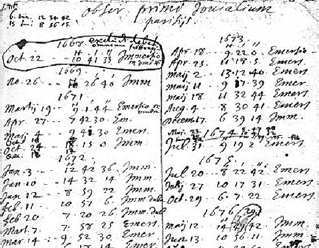

The first good estimate of the speed of light was made by the Danish astronomer Ole Christensen Røemer, who expanded on Galileo’s original idea of using the moons of Jupiter as astronomical clocks of sorts, not for measuring longitude but for measuring light time. Røemer observed hundreds of eclipses of Jupiter’s moon Io, carefully timing its disappearance into or reappearance from Jupiter’s shadow. He noticed that the predicted eclipse times differed from the observed times in a systematic way: they occurred about 11 minutes earlier when Earth was closest to Jupiter, and 11 minutes later when Earth was farthest away. Røemer deduced that the difference was because of the finite speed of light. With the help of his Dutch colleague Christiaan Huygens, the speed of light from Røemer’s eclipse data was estimated to be about 137,000 miles (220,000 kilometers) per second. While the actual value was later determined to be about 35 percent greater, based on the more definitive eighteenth-century stellar aberration measurements by the English astronomer James Bradley and the nineteenth-century Michelson-Morely Experiment, Røemer’s insight and years of careful observing enabled the first good estimate of the speed of light.

Part of Ole Røemer’s observation log book with recorded times for some of the Io eclipses that he used to estimate the speed of light.

SEE ALSO Galileo’s Starry Messenger (1610), End of the Ether (1887).

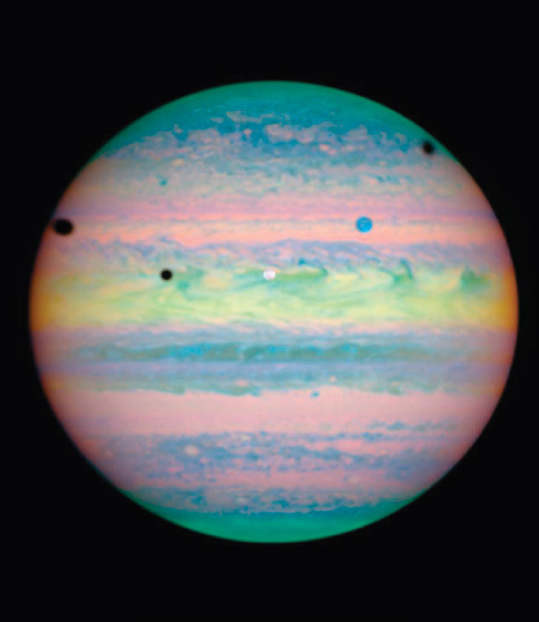

Hubble Space Telescope false-color infrared photo from March 2004 showing Io (center) and Ganymede (right) transiting across Jupiter’s disk. The shadows of Ganymede and Io are at left and the shadow of Callisto (itself not in the image) is at upper right.