1859

Solar Flares

Richard Carrington (1826–1875)

The Sun is the most massive, energetic, and important (to us, at least) object in the solar system, and so it should not be surprising that many nineteenth-century astronomers chose to train their increasingly powerful telescopes on our nearby star in order to study its inner workings. By using proper filters or projecting the solar disk onto a wall or screen, astronomers could measure and monitor features like sunspots on the Sun’s visible “surface,” the photosphere. Sunspots had been studied for centuries, with systematic observations going back to the early seventeenth century revealing an eleven-year cycle of repeating solar activity. Improvements in telescopes and observing methods allowed them to be studied in ever-more exquisite detail.

One of the most noted and prolific observers of sunspots was the English amateur astronomer Richard Carrington. On September 1, 1859, Carrington observed an intense brightening near a particularly dense cluster of sunspots. The event lasted only a few minutes. The next day, however, saw reports worldwide of intense auroral activity and major disruptions to telegraphs and other electrical systems.

What Carrington had witnessed was the first recorded example of a solar flare—an enormous explosion in the Sun’s atmosphere that can hurl high-energy particles at enormous speeds out into the solar system. The dramatic effects from this solar “wind” crashing into the Earth’s protective magnetic field is known as a solar storm. Many such flares and storms have been observed since then, but visual records and ice core data indicate that the 1859 event was not only the first but also the largest in recorded history—perhaps a once-in-a-millennium mega flare.

Carrington’s scientific observations established a connection between the Sun’s activity and the Earth’s environment, and led to intense interest in the study of space weather—the interaction of the solar wind with all the planets. Today’s armada of Earth-orbiting satellites, in particular, represents billions of dollars of technology and infrastructure that is highly vulnerable to disruption by solar flares and their ensuing storms, especially during times when sunspot activity is high. This is just one reason why NASA and other space agencies are highly motivated to continue Carrington’s important work of predicting, monitoring, and understanding the effects of space weather.

SEE ALSO Birth of the Sun (c. 4.5 Billion BCE), Astronomy in China (c. 2100 BCE), Mira Variables (1596).

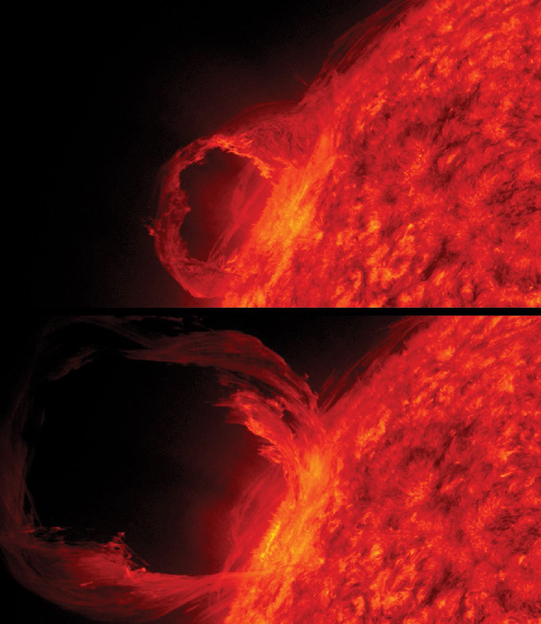

A spectacular solar prominence eruption captured in time-lapse frames on March 30, 2010, in the extreme ultraviolet light of ionized helium by the NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory satellite. For scale, hundreds of Earths would fit into the loop in the top frame.