As I moved the tired and aching man away from his latest admirers of the moment at the golf club and toward his spot in the middle of the room for the CNN filming, I had several thoughts in rapid fashion.

First, somehow we made it. That was despite everything:

- The phone call I received out of nowhere earlier that morning from Hank Aaron, saying he was ready to do the CNN interview, but he said he only felt good enough to do it right then.

- The need to search my home in a rush for stuff that might fit Henry Louis Aaron, especially after he said he had nothing to wear due to his lengthy stay in mostly a bed away from home.

- The horror to discover upon my arrival at the “rehabilitation center” that it really was a nursing home.

- The sight of the tired and aching man sitting on the edge of a bed in the body of Henry Louis Aaron.

- The messages I kept getting from CNN folks—Hurry!—as I tried to maneuver the tired and aching man down the hallway in John Wooden style. (Be quick, but don’t hurry.)

- The rain, the endless rain.

- The struggle to move the tired and aching man out of the wheelchair and into the front passenger seat of the massive SUV.

- The starstruck SUV driver (or rather, the Henry Louis Aaron-struck SUV driver) who wouldn’t stop talking.

- The need to maneuver through the hidden areas of the golf club with the tired and aching man in a wheelchair as further proof that Hank Aaron fans were everywhere.

That other thing also sprinted into my mind: from the time Hank called me a couple of hours earlier to right then, I hadn’t spent a millisecond preparing questions for baseball’s greatest player ever for a one-on-one interview I was about to do on national television.

I told the producer I needed 10 minutes. He said I had about five. Afghanistan was waiting, you know.

While the makeup woman dusted the shine from my face, I scribbled a few key points into my reporter’s notebook and then I prayed. It was a simple one because I hadn’t a choice: Lord, help me, please! Then, after the producer urged me to hustle into one of the two chairs facing each other in the middle of the room—with the bright lights glaring, and with the cameras preparing to roll, and with more people in the room than was needed for such a thing, I noticed something.

Across the way, I didn’t see the tired and aching man. The wheelchair was nowhere in sight. It was vintage Henry Louis Aaron, looking fresh and vibrant even beyond what the makeup woman did with her spraying, rubbing, and patting around his 80-year-old face of fame. He sat in a chair, a regular chair, the kind that was perfect for the setting. Imagine a large family room complete with classy pictures, crown molding, a fireplace in the corner, and the kind of furniture your Aunt Flossie would purchase to make everything cozy.

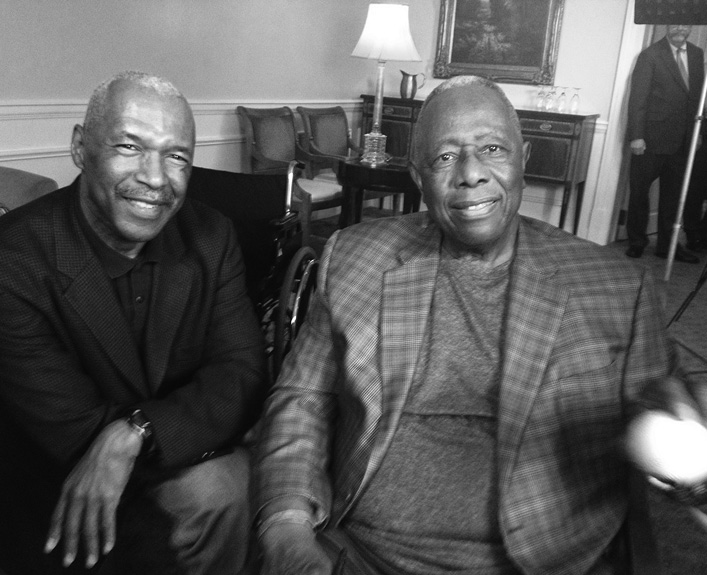

Courtesy: Aric Thompson/Dream Multimedia Group Inc.

Then there was Hank, smiling his smile, donning mostly his clothes and some of the ones I brought. Casual was the theme. We both wore sports jackets, jeans, and sneakers. He was so relaxed. By the time the producer said the cameras were rolling for this interview that was “live-to-tape” (meaning no do-overs, not with Afghanistan always waiting in the background), it felt familiar. It felt like nobody else was there. It felt like all of those other times Hank and I spoke privately about everything you could name.

It felt spiritual.

I had those points of emphasis, sitting on my lap inside of that reporter’s notebook, but I didn’t refer to them. It wasn’t necessary. With Hank right there, replacing the tired and aching man, this was the kind, eloquent, wise, humble, funny, reflective, charitable, enjoyable man—who just happened to be the greatest baseball player ever as well as one of the biggest civil rights icons in American history—right there. This was the man I spent more than 30 years huddling with at that point either on the phone or in person.

I spoke to Hank Aaron during that CNN interview the way I normally spoke to Hank Aaron, and he did the same with me. Hank provided more insight than he ever had before regarding both his kinship with Jackie Robinson and everything surrounding April 8, 1974, when he surpassed Babe Ruth’s record of 714 career home runs in Atlanta. Afterward, things got personal during the interview as I provided just one of the many reasons I was born to become The Hank Aaron Whisperer.

“I can remember clearly that Monday, the night you hit the home run. The parents, the two brothers, and I gathered around the television set,” I said. “It was very similar—it had to be—to where, back when you and others back on April 15, 1947, gathered around the radio for Jackie Robinson. I mean, you were our Jackie Robinson. Did you get the sensation of how important you were to the Black community in what you were doing, in what you were going through?”

“Yes, I did,” Hank said. “In some ways, I felt the importance of what I was doing was really sending a signal to the world, was telling people that, ‘Hey, yeah, all we wanted to do was have the playing field level. Just give me an opportunity.’ Yes. I felt that way. I felt that way that not only did I have the world on my shoulders as far as baseball was concerned, but I also had the world on my shoulder to demonstrate that, hey, just give me the opportunity. But at that same time, if you think about it, Dr. King was marching, and civil rights was at its peak, and we were just telling people to just give us a chance to drink water out of a fountain,” he said, laughing, “or to go to the bathroom or to go anywhere really. And [trying to improve] all those things had something to do with what I was doing as far as playing baseball.”

“Then came that moment…when you were running around the bases. I’ll never forget this because you could hear this bang, bang! There were fireworks, but were you thinking about something else?”

“No, not really. I wasn’t thinking about much of anything. But speaking of that, a very good friend of mine, he was on the [Atlanta] police department at that time. I don’t know if you or anybody would notice, but any picture you would see of him, you would see he would have a little briefcase, just a little thing around his neck. And on the inside of that little thing was a snub nose .32. He told me, ‘Hank, I didn’t know what to do when you started running around those bases [after hitting No. 715]. Then you had those guys running behind you [as fans from the stands].’ I told him, ‘I’m glad you didn’t shoot because those two guys were having nothing but fun.”

Hank could rejoice as well because the chase was over.

We continued to talk as the cameras rolled and then we talked some more. We talked about Hank’s calling in October 1972 to take the place of the late Jackie Robinson as an outspoken former sports star on social injustice and we talked about how the likes of Willie Mays and Ernie Banks wanted no part of it. We talked about the plunging number of African Americans involved with baseball.

We talked about Barry Lamar Bonds.

“Barry Bonds—to me—is not the legitimate home run king. You are the legitimate home run king,” I told Hank.

“Why, thank you,” he said.

“Yes, and for various reasons. But throughout that entire run, you never said anything negative about Barry Bonds, and that’s something a lot of people couldn’t do during that stretch. You were able to hold it in.”

“Well…and it wasn’t trying to hold anything in. That’s just the way I am. I felt like I had been through an awful lot, chasing Babe Ruth’s record. I know exactly…Some guy wrote me a letter, and he asked me and he said, ‘Hank, if you can—without calling his name—if you can come and follow Barry for the next four or five days before he hits the [record-breaking] home run, we’ll give you $300,000 for each game.’ You know, for each game.”

“I think I would take that,” I said, laughing.

“I told him, ‘I don’t think I want it. I don’t need it.’ I don’t want it because I didn’t want to get involved in it. This was Barry’s time to shine. It was his time for people to look at him being who he was, and I was not going to take anything away from him and I said, no. So, I decided I wasn’t going to take it. But no, I refused to get involved with that and for a lot of reasons really and for one reason I just mentioned. And for another reason: I know that Barry—and not only Barry—some of the other players were involved in doing some shady things [referring to steroids], but I had no concrete evidence about it and I wasn’t going to get involved in it. I was waiting for [other] people to make that judgement.”

A few Hank stories later, the interview ended.

There were “wows” around the room, along with a few wet eyes from members of the CNN production crew. They were moved by Hank’s distinctive voice delivering captivating thoughts for nearly an hour. They all said the same: it was as if Hank Aaron was sitting in your living room, just chatting in private about all sorts of things with somebody he knew for decades, which was the case since I was The Hank Aaron Whisperer.

As the camera folks scrambled in the background to stuff pieces of this and that into various containers for their Afghanistan dash to the airport, others in the room gathered around Henry Louis Aaron for an autograph or for a handshake or for a personal message of thanks not only for Hank doing the interview, but also for Hank being Hank over the years.

I gave the CNN folks and others time for some of that. Then I had to become The Hank Aaron Enforcer again. Even though I still saw Henry Louis Aaron in the chair across the way with the vintage smile and the “Why, thank you” responses, I suspected it was a combination of adrenaline and his eternal graciousness toward others. The makeup woman rubbed the powder from his face, and I rushed to the other side of the room to grab the wheelchair. Some members from the CNN crew helped me slide Hank from his interview chair into the one that had become his home away from home over the previous weeks.

I thanked everybody on my way through the door while pushing the wheelchair with John Wooden in my head again. Be quick but don’t hurry. I knew Henry Louis Aaron was on the verge of evolving back into the tired and aching man, which he did. He tried to hide it, but as I moved through the back hallways of the golf club, I could tell he was exhausted. “Hey, we’ll get you back to the place in no time,” I said, as he looked up and gave me a smile and a nod.

I kept thinking to myself, Please, stop raining. And if we get the same SUV driver CNN sent before, I hope he has run out of stories and questions for Henry Louis Aaron.

It was still raining and it was the same driver.

He had even more stories and questions.

Even so, while the driver juggled his large umbrella in one hand to battle the pounding rain, he did do a better job this time of using his other hand to help me raise Hank out of the wheelchair and into the top of the skyscraper, which described the distance from the sidewalk of the golf club to the floor of the gigantic vehicle on the front passenger’s side.

The ride back seemed quicker probably because my phone wasn’t buzzing anymore about ETAs and Afghanistan. There also was this: the closer we got to the nursing home disguised as a rehabilitation center, the more I saw the return of the tired and aching man. In my mind he was sitting there, dreaming of replacing his hodgepodge collection of clothes with a soft pair of pajamas.

After we arrived the driver performed his circus act again. He maneuvered his umbrella against the raindrops and he used his other hand in conjunction with both of mine to proceed with caution as we transferred the tired and aching man from the front passenger’s seat into his wheelchair while keeping him dry. I thanked the driver, but Hank thanked him more because that was Henry Louis Aaron being Henry Louis Aaron. Then I rolled the tired and aching man back into the facility right by many of the same faces who greeted us on the way to the golf club, and the messages were similar.

“Hey, Hank.”

“How you doin,’ Mr. Aaron?”

“I see ya, I see ya.”

“There goes Hammer.”

Just like before, the tired and aching man acknowledged every one of them in his easygoing way. Sometimes he motioned for me to pause, so he could deliver an extra sentence or three to those speaking either across the way from their beds or from nearby in wheelchairs of their own. We finally arrived at his room filled with quiet, and as I steered the tired and aching man over to his bed, it hit me again: I’m pushing the greatest baseball player of all time around a nursing home in a wheelchair!

I wanted to cry…again.

I probably did but only on the inside.

Outwardly, I remained upbeat for the tired and the aching man who had done so much for me. There was the present, when he called me that day to do a CNN interview he probably shouldn’t have done. He helped me survive my Dixiecrats for nearly 25 years at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution while we compared notes about his. He gave me an even deeper appreciation for Jack Roosevelt Robinson since he was the same guy in spirit. He made me laugh and he mostly wasn’t trying. He reminded me so much of uncles, of cousins, of neighbors, and of Samuel Moore, my father who was nearly the same age. He was a pretty good baseball player, too. I still had my Hank Aaron poster—the one I bought at 12 years old, the huge one, matted and signed by the man himself, inside of a glass frame, and hanging prominently in my home.

“Anything else you need?” I asked after I thanked the tired and aching man for everything as he sat on the edge of his bed.

“No, Terence, thank you,” he said before he turned into Henry Louis Aaron with one of those smiles that hinted something else was coming. “I’ll tell you what I need. I need some sleep.”

We laughed, as I headed for the door.

I looked back, then I looked back again. I thought that might be the last time I would see Henry Louis Aaron, but as Hank would say, “the Good Lord” gave me, along with everybody else, another seven years. Hallelujah.