9.

UP FROM PARTISANSHIP

“I would unite with anybody to do right; and with nobody to do wrong.”

FREDERICK DOUGLASS1

What does injustice look like? For Weldon Angelos, that was a question he thought he’d be contemplating for 55 years.2 Weldon had a bright future in music. He started a hip-hop label, Extravagant Records, and caught the attention of some of the biggest names in the industry, including Snoop Dogg and Tupac Shakur. Weldon was on track to do well for himself.

Unfortunately, Weldon made a poor decision to finance his music career: selling drugs. In the early 2000s, as the War on Drugs was raging, he sold a small amount of marijuana to a confidential informant on three occasions, allegedly carrying but not brandishing a gun for one of them. The local police swooped in to catch their criminal.

Weldon Angelos made a mistake. He broke the law. But if we want laws to be respected, then laws must be respectable. And the law in this case was anything but.

The prosecutor convinced a grand jury to indict Weldon on 20 counts. More important than the number of charges was the length of prison sentence they required. The indictments dealt with crimes covered by “mandatory minimums,” which set minimum prison terms. This lets ambitious prosecutors “stack” penalties, ensuring that a possible sentence skyrockets as charges are added.

At the trial’s end, Weldon Angelos was convicted of 13 of the 20 charges. Even though he was a first-time, nonviolent offender, he was handed a non-negotiable prison sentence of 55 to 63 years.

Before the sentencing, nearly 30 former prosecutors and judges wrote a letter condemning Weldon’s treatment. The judge who handed down the sentence called it “unjust, cruel, and irrational”—a demonstrably true statement, given that Weldon would have spent less time in prison for committing rape or an act of terrorism. But the law tied the judge’s hands and forced him to bind Weldon’s hands for more than half a century.

Fortunately, Weldon’s story didn’t end there. A growing chorus of voices, including mine, spoke out against his treatment, leading the same prosecutor who originally went after Weldon to have a change of heart. He helped persuade the federal courts to release Weldon from prison in 2016, just in time for his eldest son’s high school graduation. His sons were only six and four years old when he went to prison. His daughter was an infant. They spent 12 long years without their father in their lives. Now they have him back.

Weldon’s reprieve was more than overdue. Yet his case is the exception. The criminal justice system is still rife with barriers that injure those in prison, their families, and, ultimately, society. It exemplifies the kind of injustice that arises when government policy goes awry.

GOVERNMENT’S VITAL ROLE

One of government’s responsibilities is keeping us safe from crime. The police and the military are responsible for protecting us from violent threats. Criminal justice is such an important part of government’s role that fully five of the 10 amendments in the Bill of Rights deal with police powers and the criminal justice system.

This makes sense. Government, at its best, fosters the rules of just conduct that enable individual success and societal well-being. As the institution with the legal monopoly on the use of force in a given geographic area, it is the only institution in a position to protect equal rights, set and enforce laws, and restrain those who threaten our person and property.

The Declaration of Independence articulates the vision of a just government: one that secures to all the inalienable rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Insofar as America has pursued this vision, our country has made incredible progress.

To realize this vision, government upholds the rule of law and uses force only in those areas where force works better than voluntary cooperation and competition. It gives the other institutions the space they need to fulfill their roles while fostering a system of mutual benefit. This provides people with an environment in which to flourish, enabling everyone to discover, develop, and apply their gifts. Without a beneficial government, individual and societal success is impossible.

Yet beneficial government is not what most Americans believe our country has. A mere 17 percent trust government to do what’s right.3 Overwhelming majorities of Republicans, Democrats, and Independents hold these views. How did we get to a place where close to everyone agrees that government is broken?

I submit that the problem isn’t government by itself. As with all our institutions, the source of the problem is what we as a society expect it to accomplish, and how we use it. Too often when we see a problem, our first impulse is to look to government to solve it. Rather than finding cooperative solutions grounded in individual empowerment, we separate into camps to fight over how government can best address our problems. Instead of starting from a point of unity, we start from a place of division.

TWO TRIBES

Welcome to the crisis of partisanship.

More than two hundred years ago, George Washington declared that political parties are likely “to become potent engines by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government.”4 Time has proven our first president correct.

Whether at the local, state, or federal level, politics is almost always divided between two warring sides, both of which constantly try to damage and defeat the other. They try to arrange policy and politics to their maximum advantage, and to their opponents’ maximum disadvantage. The focus is not on public policies that empower people and improve their lives; it’s on political victory at any cost.

Partisanship is a form of tribalism, which is exactly what it sounds like: different tribes duking it out for supremacy. Where once the tribes used weapons of war, now they use television ads and microtargeting. The motivation remains the same, however: to ensure that your tribe comes out on top—and, equally important, that the other comes out on the bottom. This isn’t just zero-sum, it’s negative-sum.

Tribalism makes it very difficult to get good things done in government. It shifts attention from policy to politics, from empowering people to beating up the other side. Instead of working together, people and parties focus on staying in control, propping up allies, and punishing or scapegoating opponents.

Tribalism also makes it harder for Social Entrepreneurs to break down barriers. The way that politics works means that before attempting to solve problems, people must first try to hamstring their opponents. Mutual benefit is a foreign concept. Pitting people against each other is the name of the game. And I use the word “game” because that’s how so many treat it, as a contest to win by any means.

DUMB ON CRIME: A CASE STUDY

What does this have to do with Weldon Angelos? Everything.

Tribalism led politicians on both sides of the aisle to misuse government power for their advantage. On criminal justice, they found that bad public policy made good party politics.

Have you ever heard the phrase “tough on crime”? Politicians of both parties have used this phrase to sell dangerous and destructive policies for many decades. They come out looking like the defenders of public safety while casting their opponents as “soft on crime.” Yet their victory comes as a loss, not only for their political adversaries but also for people like Weldon and their communities (more on that later).

It has worked this way since at least the late 1960s. Perhaps the most infamous example of this style of politics was the “Willie Horton” ad that ran in the 1988 election. George H. W. Bush was able to convince voters that Michael Dukakis was weak because a man committed a heinous crime when he was released from prison through a weekend furlough program.

Tribalism led politicians on both sides of the aisle to misuse government power for their advantage.

The lesson for politicians: you’ll get blamed for the bad things that happen as a result of the policies you pass, overshadowing any credit you get for the good things that happen from those same policies—even if the good far outweighs the bad.

From that moment on, any politician who considered reforming the criminal justice system was warned by political consultants, “If you do that, you’ll get Willie Hortoned.”5 And instead of focusing on public safety and making the criminal justice system more just, politicians have made it more unjust in the rush to seem tough on crime.

Hence we have a criminal justice system that defies logic and ruins lives. Incarceration has exploded in recent decades. More than two million people are now behind bars in this country—four times more than in 1980.6 While the United States contains 5 percent of the world’s population, the fact that it has 20 percent of the world’s prison population is a national disgrace.7 Moreover, the fact that justice is not applied equally, with communities of color suffering disproportionately from the system’s inequities, is a national tragedy.8

In the early 1980s, the federal criminal code contained 3,000 offenses.9 Nearly 40 years later, after endless partisan one-upmanship, a definitive count can no longer be determined.10 The best guess is that the number of federal criminal laws is somewhere north of 4,400.11 Additionally, there are now more than 300,000 federal regulations with criminal penalties.12

Legal expert Harvey Silverglate wrote a book titled Three Felonies a Day, which refers to the number of felony crimes committed daily and unwittingly by the average person.13 In their zeal to be tough on crime and defeat their opponents, partisans on both sides of the aisle have criminalized a vast swath of regular life.

Many of these laws contain the sort of mandatory minimum requirements that nearly destroyed Weldon Angelos’s life. Most mandatory minimums were instituted in the 1980s and 1990s, and many were created even after violent crime rates had already started falling.14 Far from being a needed policy tool, they were more a political tool to show that lawmakers were “doing something.”15

Whatever the reason, currently around 90,000 federal inmates—more than half the federal prison population—are serving sentences controlled by mandatory minimums.16 States have enacted mandatory minimums of their own, which helps explain why state prison populations soared by more than 220 percent between 1980 and 2010.17

Prosecutors like mandatory minimums because they get more leverage. If someone feels like they are destined to spend a long time behind bars, then a plea bargain that admits guilt for a lighter sentence is much more appealing. Even an innocent person may be inclined to take that deal, given the possible alternative of a lifetime in prison. This explains why 97 percent of federal criminal cases (and 94 percent of state cases) end in plea bargains rather than a trial and a chance to defend oneself in court.18 It’s not how the system is supposed to work.

By imprisoning so many people for so long, we’ve made it harder for them to develop skills and find employment after their release—controlling, rather than empowering, or at least rehabilitating, them.

About 95 percent of those who are incarcerated will be released, and it’s in everyone’s interest that they be able to succeed, rather than blocked from contributing.19 But various laws and policies limit their post-release options in at least 44,000 ways, more than two-thirds of which make it harder to find a job.20 Within a year of obtaining freedom, more than half still lack any employment, often because businesses won’t or can’t hire people with criminal records.21 Those who find jobs make an average income of only $9,000—well below the poverty line.22

This creates a new cycle of despair and crime. Cut off from the ladder of opportunity, many feel that they have no good option but to break the law again. More than three-quarters of those who leave state prisons will be arrested again; the same is true for almost half of federal inmates.23 This removes people, especially men, from their neighborhoods and families.24 A staggering 2.7 million children have a parent behind bars, devastating a generation of kids during their most formative years.25 The consequences will be felt for the rest of their lives and across all of society.

For all this, the criminal justice system leaves many people less safe. While crime rates overall have been declining for decades, some well-meaning policies have led to more crime.26

This is true for low- and moderate-risk defendants who are jailed for a time before trial. Their time behind bars often causes them to lose jobs and harms their families, pushing them toward crime to make up for whatever they lost.27 More broadly, multiple studies have found that incarceration doesn’t deter crime and may increase it, compared to alternative punishments.28 To put it simply, the criminal justice system creates repeat offenders and at least as many problems as it prevents.

Partisan tribalism helped build these barriers. It also makes them harder to knock down. The problems with the criminal justice system have become obvious to many, yet partisan and ideological divides have made people hesitant to collaborate and hostile toward each other. Social Entrepreneurs have struggled to make progress.

Small-government conservatives generally look at the justice system and see all the hallmarks of the failure of “big government.” They criticize the massive increase in the criminal code, as well as the rise of offenses that don’t require the lawbreaker to have criminal intent. These two developments have correctly convinced many right-of-center reformers that criminal law is out of control and needs to be scaled back.

While conservatives look at injustice in the laws, liberals look at injustice in their application. They see gross racial disparities, such as how African Americans comprise 13 percent of the U.S. population but 33 percent of the prison population.29 They also see different standards for the rich and the poor. The former can afford well-connected attorneys and often get off easy, while the latter typically get hit hard. They too rightly demand a better, fairer system.

I’ve always felt that both sides were right. Starting in the 1970s, I supported work that pointed out the inequities in criminal law enforcement. I began to ramp up my support for groups like the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, typically thought of as a left-of-center group, in the early 2000s. I also backed groups like Right on Crime that urged right-of-center organizations to get engaged on this issue.

But rather than work together, the left and right often attacked each other’s motives—conservatives saying liberals hate the police, liberals saying conservatives only want to help corporations. Such tribal sniping stood in the way of progress. The criminal justice system, meanwhile, kept ruining lives, creating new problems for communities and holding many people back.

Tribalism also held back progress in politics. I doubt that any politician set out to ruin lives, but a shocking number don’t seem to mind what’s happening. Republicans and Democrats usually don’t see how better policies would help them win the next election. So they let the problem fester, despite its terrible human cost. The parties allow the continuation of a criminal justice system that doesn’t deserve the name.

BIG PROBLEMS GET WORSE

The same sad story plays out across politics. On issue after issue, partisanship prevents the two parties from working together to do the right thing. They define themselves in tribal opposition to each other, and the very concept of cooperation cuts against that paradigm. The political incentive is to let injustices worsen, lest a solution hurt them or help their opponent.

Is it any wonder that America’s biggest problems keep getting worse?

On foreign policy, the country is embroiled in endless war, costing thousands of promising young lives, wasting trillions of dollars, and making America less safe and the world more chaotic.

On healthcare, people are getting priced out of the treatments they need, while quality care keeps getting harder to find, despite decades of policies meant to solve these problems.30

Government spending continues to set records, year after year, even though the country can’t pay for it. Thanks to spending sprees by both parties, the national debt is already more than $26 trillion and will, on present course, add significantly more than a trillion dollars every year until kingdom come—an unsustainable trajectory.31

ALICE JOHNSON

I AM BUT ONE PERSON

ALICE MARIE JOHNSON WAS SENTENCED TO LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE IN 1996 FOR PASSING ALONG MESSAGES TO COCAINE DEALERS—A NONVIOLENT FIRST-TIME OFFENSE. AFTER HER SENTENCE WAS COMMUTED IN 2018, SHE PARTNERED WITH STAND TOGETHER TO SUPPORT CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM.

When I entered prison, my paperwork reflected that my projected release date would be death. I was told that the only way I would ever be reunited with my family would be as a corpse.

No parole board would ever hear of my remorse for being involved in criminal activities. In federal prison, life means life. There would be absolutely no opportunity for redemption.

These were all the ingredients of a hopeless situation. But my faith in God allowed me to see beyond bars, to hear beyond words, to dream beyond doubt.

My incarceration affected more than just my freedom. It had a domino effect. Because when a person goes to prison, their entire family goes with them. Their entire community goes with them. There is no measure or analysis of the true effect that incarceration has on society. Yet we see it and feel it.

I’ve been asked how I was able to find purpose in prison. But actually, my purpose found and embraced me.

When I looked around and saw so many hurting and dejected people, it awakened in me a passion to make a difference.

It is so heartbreaking to see women who are in hospice care in prison, dying alone in a lonely place. It somehow takes away the last bit of dignity a person has. I became a hospice certified volunteer so I could care for and offer companionship to women so they would not die alone. I could make a difference in someone’s life.

Alice Johnson transformed her life while serving a life sentence in prison for a nonviolent first-time offense. Just months after her sentence was commuted, she was advocating for criminal justice reform at a Stand Together summit. (Palm Springs, 2019)

While in prison, I met a woman whose legs had been amputated from the knees down. She told me the thing she missed most was the ability to dance. So I helped coordinate the first Special Olympics in prison for women with mental and physical challenges. For this work, I received a Special Events Coordinator of the Year award in 2011. At the awards ceremony, the woman with no legs was able to dance to a song that I choreographed for her called “Never Give Up.”

I found women who were hungry for someone to believe in them and see that there was something they could do. So I started mentoring women in theatrical productions. One of my good friends, Christie, was under my mentorship for four years. When I met her, she was a shy woman who couldn’t even look you in the eyes and kept her head down. She later produced an original play that had four productions in a single year.

The day I left prison will forever be etched in my mind. When the announcement came across the loudspeaker—“Alice Marie Johnson, report to Receiving and Discharge with all of your properties”—there was a deafening cry that went up in the building.

As I walked out of the door, women were in every single window, beating on the bars and screaming my name. As I left the prison, I passed by a low-security camp. Every one of the 250 women, and all the officers and guards, were standing outside waving and crying and rejoicing to see me released from my life sentence.

Now I’m fighting for those women and men who have been left behind in our country’s prisons. I promised I would not forget about them. I have not. I never will.

I am but one person. You are but one person. But together, we are many. And we can make a difference.

— ALICE JOHNSON

Watch Alice’s presentation to the Stand Together community at BelieveInPeopleBook.com/stories

Corporate welfare, including protectionism, is growing in size and destructiveness.32 The economy is more rigged by the day.

And on immigration, a broken system stays broken, condemning people who want to come to America and contribute. The plight of the Dreamers—the million-plus undocumented immigrants who were brought here as children—is especially urgent. Those who are, or will be, contributing are held back by the fact that they could be deported at any time.

More than 80 percent of Americans want the Dreamers to stay.33 Leaders of both parties say they want the same. And yet both sides see the Dreamers as a rallying point for their political base and so are content to do nothing but demonize the other side. Meanwhile, good people who are already making our country better are suffering. It’s unjust and counterproductive.

There are many other pressing issues I could name that Americans want and need solved. The us-versus-them mentality dominating politics all but assures that nothing positive will happen. The incentive with partisanship is to use problems as weapons to beat the opposing team instead of empowering people. In many cases, our leaders use people’s suffering to score political points. What’s good for the parties today is usually the opposite of what’s good for Americans.

Can America survive as a country if our citizens despise each other?

Worse, partisanship is pushing the parties toward extremes, including ideologies and policies that are demonstrably destructive. It is also convincing people to hate their fellow Americans. About half of the members of each party already think the members of the other party are “ignorant” and “spiteful.” More than a fifth of each party views the other as “evil.”34 Can America survive as a country if our citizens despise each other?

PARTISANSHIP DOESN’T WORK. I SHOULD KNOW.

For me, this question is far from academic. In my own work as a Social Entrepreneur, I have tested the proposition that partisan politics can cure what ails society. My conclusion: partisanship doesn’t work.

I avoided partisan politics like the plague from the 1960s to the 2010 election cycle. The “Congress Critters” and presidential candidates who often came calling seemed like nice enough people—some of the time—but I didn’t see the point of engaging with them. Koch Industries has never been in the business of asking for favors, and outside of the company, my focus was mostly on education.

With time, however, it became clear that helping people required more than educational efforts in schools, universities, and think tanks. We also needed to change the policies holding millions back. So the philanthropic community that I founded got involved in electoral politics. We bet on the “team” that seemed to have more policies that would enable people to improve their lives. You only get two choices in our system, so we chose the red team.

We should have recognized right from the start that this was far too limiting. The “team approach” means that to get the policies that you think will help the country, you have to take all the other policies your team is offering, even if you disagree with many (or most) of them.

Your options winnow further once your team tries to make the other team look bad. You oppose the other party’s policies, no matter how good or bad they are, simply on the grounds that they’re the other party’s policies.

Even if your team wins the election and gains power, it’s usually not a victory from a policy perspective. You’ve already narrowed the list of things that are possible. With the other team still fighting you at every step, many of those policies are pushed out of reach. By that point, you’ve spent so long fighting the other team that the idea of collaboration seems like a sick joke.

Meaningful achievements—policies that enable more people to flourish—become difficult and rare in this environment. Your team has an incentive to build barriers instead of knocking them down. The whole system pushes beneficial government out of reach.

The quick version is that partisan politics prevented us from achieving the thing that motivated us to get involved in politics in the first place—helping people by removing barriers. I was slow to react to this fact, letting us head down the wrong road for the better part of a decade.

Boy, did we screw up. What a mess!

Once this became clear, we changed our approach. Far from withdrawing from politics, we decided to get more involved. But instead of picking a team and figuring out who would work with us to get good policy passed, we decided to skip the first step and do a better job of the second. We now work with people on the red team, the blue team, or no team at all! We now go issue by issue and work with anyone, regardless of political party.

In short, we abandoned partisanship and chose partnership instead. This simple distinction has made all the difference. It is key to transforming government, so it is key to helping every person rise. In matters of public policy, partnership is a better way.

In short, we abandoned partisanship and chose partnership instead. This simple distinction has made all the difference.

GRATITUDE, ALWAYS

ONE OF THE MOST painful periods of my life was also one of the longest. It ripped our family apart and nearly destroyed the family business.

It all started in 1980, when two of my brothers and another stockholder tried to take over the company and steer it in an entirely different direction. My brother David, I, and a sixth shareholder disagreed and blocked the attempt. They sued, which led to our buying their stock. It looked like a win-win—they’d get the money they wanted, and we’d continue to run the business the way we believed was right.

Unfortunately, they filed many more lawsuits, the story of which has already been told many times. Mercifully, the onslaught finally ended in 2001—21 years after it started.

For many years, I took the lawsuits in stride, but that got more difficult as their main suit approached trial in Topeka in 1998. I became completely absorbed with preparing for it. So did a growing number of our executives, leading to increasingly bad business decisions in the company.

By the time of the trial, I was in a deep depression. I could barely function. Although we were confident we did nothing wrong, I could see that there was a risk they could spin these complicated events in a way that might convince a jury. Ultimately, the jury ruled in our favor—we won. After the trial, the judge wrote that if he had known earlier how little the other side had, he would’ve thrown the whole case out. But my depression continued for at least another six months.

Recovery from this kind of depression is never easy. It required refocusing my mind by working hard to get the company back on track, daily exercise, and a supportive community, especially Liz and our children.

It also helped to reflect on what I’d learned from the Stoics years before. Those Greek and Roman philosophers believed that we should be grateful for everything—our mistakes, our struggles, even our adversaries.

The difficulties we face ultimately make us who we are. Even the most painful parts of our life can cause us to realize what matters and recognize where to go next. That helped me realize that my brothers had done us an enormous favor. We didn’t share vision and values, so if they had stayed in, the company could have been forever crippled. We never would have been able to accomplish a fraction of what we have.

I look at my experience with partisan politics through the same prism.

As far as mistakes go, it was a big one. And the vitriol that came with it is hard to describe. But without the pain of that experience, without the benefit of the lessons learned, I wouldn’t be as passionate as I am now about our current path. I wouldn’t have the same appreciation for the need to partner with such a wide diversity of truly inspiring people.

As with the rest of my life, I’m grateful for everything and everyone who enabled me to get where I am today, whatever part they played.

— CHARLES KOCH

This concept applies to every Social Entrepreneur. At its most basic level, partnership is what Frederick Douglass meant when he said, “I would unite with anybody to do right; and with nobody to do wrong.” It means adopting an attitude of mutual benefit and working with others to achieve policies that will empower people. You may disagree with someone on 99 percent of issues, but that 1 percent offers you the chance to join forces. Instead of demanding all or nothing, partnership treats people with the respect they deserve and recognizes that, whatever our differences, we always have things in common.

The hardcore partisan will tell you that partnership is impossible—a feel-good, naïve pipe dream. Their argument boils down to a simple assertion: help their preferred party win, and society’s problems can be fixed. No cooperation necessary. Yet decades of evidence prove this doesn’t work. Einstein had a word for this: insanity! You should ask those who advocate for business as usual in politics: Why should we expect things to be different after the next election?

THE PEOPLE KNOW BETTER

Here, as in many cases that we’ll see in the next chapter, the American people are way ahead of the political class. A growing number of Americans are rejecting what they’re selling.

The data show that partisanship no longer appeals to the American people. Over the past three decades, both Republicans and Democrats have gone from net favorable views to net unfavorable views among the wider population. Three in five Americans feel that neither party represents them. A whopping 83 percent of Americans say tribal divisiveness is a “big problem.” More than 90 percent want to stop it and find some way to bring people together.35

For that matter, many politicians are sick of the partisan B.S. This may sound crazy, but I don’t think politicians are bad people—with perhaps some notable exceptions. I think most of them ran for office because they wanted to help others. They’re just as beat down by pressure to get reelected and bickering brawls as the rest of us. I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve heard a politician say, “This isn’t why I ran for office” or “This isn’t why I came to Washington.”

Clearly, Americans want a better way. So do the leaders we elect. They continue to double down on partisanship because they think that’s all there is. Politicians honestly believe their only option is to beat the other side, and voters are left to decide which is the lesser of two evils. Yet if the recent past proves anything, more partisanship will only further divide people and turn them off while leading to less individual empowerment and societal progress. The only sure thing that happens when you fight fire with fire is that you burn the house to the ground.

So instead of constantly raising the tribal temperature, maybe it’s time to cool things down. Partnership does that, helping any Social Entrepreneur become more effective.

The lie of tribalism is that your gain must come at my political expense. It is inherently exclusionary, a project of division. Partnership, by contrast, is naturally inclusive, encompassing more and more people from different backgrounds. It’s a project of addition. It means we can all win together—and the bigger the “we,” the bigger the win.

This is the essence of bottom-up transformation. When people unite, they prove to each other that we can all be much more effective together. It makes people wonder why they fought in the first place.

Politicians react in turn. They’re nothing if not attuned to what their constituents are saying, and so their incentives shift under public pressure. When they see their constituents unite, they realize that they need to do the same. Instead of running toward the extremes and competing for who can propose the worst policies, they begin to see that good policy can make good politics—that empowerment is an electoral winner. Then they work with their supposed opponents to get things passed.

PARTNERSHIP IN ACTION

I know this is true because I’ve seen it happen. I have participated in these kinds of bottom-up movements, achieving policy victories that once seemed impossible.

In 2018, Republicans and Democrats worked together to pass a historic bill that eliminated some of the worst injustices in the federal criminal justice system. The First Step Act makes it possible for thousands of people with criminal records to rejoin society and start to realize their potential.36 Among other important reforms, it stops horrific practices like shackling pregnant women to the bed while they give birth and eliminates the possibility that prosecutors will “stack” mandatory minimums for first-time offenders, as happened to Weldon Angelos.37

How did this happen amid the partisan impasses I described earlier? Tribalism was overcome, replaced by partnership and mutual benefit.

The federal reform marked the culmination of a years-long process. It began when small groups of people realized they shared similar views, despite their differences on other issues. It started in the most unlikely of places (in this case, Texas) and spread from there. The beauty of bottom-up progress is that it can start anywhere, with anyone—and quickly gain steam.

The coalition that began to form included people who had no reason to work together under the tribal mentality—businesses and nonprofits, prosecutors and public defenders, small-government conservatives and progressive activists, religious groups from many faiths, and many others. They came from think tanks, academia, grassroots organizations, and communities that had suffered from the criminal justice system’s flaws. Together, we made the case for change.

Crucially, we also committed to watch each other’s backs when the politics of tribalism came after any one of us. And that’s what we did—we stuck together.

The first signs of progress occurred at the state level. Confronted with a movement grounded in mutual benefit, lawmakers (both Republican and Democrat) began to abandon the tribal mentality, making positive action possible.

With the help of this emerging coalition, from the mid-2000s to the mid-2010s, 35 states passed empowerment-based reforms of one kind or another.38 Some slashed the lengthy sentences (mandatory minimums) that locked people away for longer than appropriate. Some expanded judicial discretion on sentencing, rolling back the one-size-fits-all approach that failed to account for individual circumstances.

To tackle high levels of recidivism, some states implemented programs and partnered with private organizations to teach incarcerated individuals the values and skills necessary for success when they returned to society. These programs have been shown to reduce recidivism by an average of 13 percentage points. 39 One such effort, Hudson Link, has reported recidivism rates in the low single digits, compared to about 40 percent in New York State, where the group is based, and closer to 70 percent nationally.40 These state-based efforts relied on science and data, not the tribal politics and fear of the tough-on-crime mentality. The list goes on.

Over that same decade, state incarceration rates fell by 6.5 percent, and the federal rate by 8.3 percent.41 America experienced double-digit declines in both violent and property crime, demonstrating that less incarceration does not mean less public safety.42 Another benefit was the money it saved taxpayers. Best of all, people who had been locked away got second chances (or in some cases, the first chance they ever got), giving them a better shot at developing their skills and contributing to their communities.

As these numbers demonstrate, smart-on-crime is more effective than tough-on-crime.

The movement grew larger and louder, until Congress couldn’t ignore it. After decades of bad actions or inaction, the First Step Act passed in late 2018 by overwhelming majorities of both parties, with a vote of 87–12 in the U.S. Senate during a time that has been described as one of the most divisive in our country’s political history.43 People called the approach naïve and said it couldn’t be done just days before the law passed. They were wrong.

Partnership and empowerment carried the day. Behind this victory was a diverse coalition that continually grew in size and effectiveness. Such partnerships—and there were countless—turned criminal justice reform from an impossibility to an inevitability.

A FLUKE? FAR FROM IT

Nor was criminal justice reform a one-off. At the time, critics said it couldn’t happen again. Yet that same year, the country saw similar progress on other important issues.

Veterans’ healthcare is one. In the mid-2010s, the Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare system was overrun with scandal. The government-run hospitals were found to have secret lists meant to cover up how long veterans waited for care. In 2015, more than two hundred veterans died on wait lists in Phoenix alone.44 Across the whole VA system, more than 100,000 veterans were forced to wait too long for treatment.45 It was later found that, between 2010 and 2014, as many as 49,000 veterans may have died before the VA processed their applications for medical treatment.46

Matt Bellina was diagnosed with ALS in 2014. At a Stand Together summit, Matt and his wife Caitlin gave a heartfelt testimonial about the difference one person can make. Their courage inspires us all. (Colorado Springs, 2018)

The crisis was real, but tribalism pushed a solution out of reach. Republicans and Democrats attacked each other instead of uniting to give veterans the care they had earned. But while the politicians did nothing, regular people and veterans demanded better. Folks from across the political spectrum began working together to make transformative change a reality.

It worked. As more people demanded change, politicians put aside their differences to make it happen. Two major pieces of legislation passed with bipartisan support. The first brought accountability to the VA, allowing for the quicker firing of staff who mistreat veterans.47 The second brought real choice to veterans’ healthcare.48 America’s veterans are now empowered to choose the healthcare provider that’s best for them, public or private. Partnership, not partisanship, made these achievements possible.

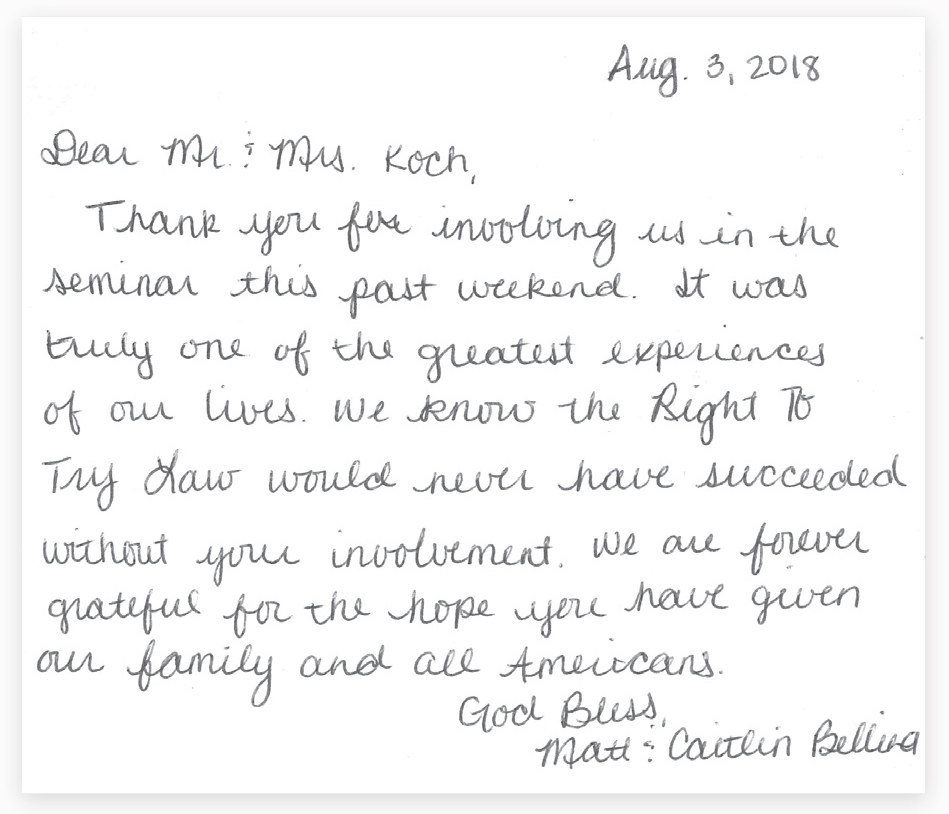

Matt and Caitlin sent me this note in 2018 thanking the Stand Together community for its role in passing the Right to Try law.

The same is true with another healthcare policy, what became known as the Right to Try.

Most people will never hear about this issue, but for some, it’s a matter of life and death. Imagine your spouse or, god forbid, one of your children is diagnosed with a terminal illness. A doctor looks you in the eye and says they only have a few months or a few years to live. Their disease has no known cure.

After the federal Right to Try law, Matt was able to access an experimental treatment to extend his life, and, in 2019, it gave him a limited ability to stand again.

But there may be another option. Innovative companies are developing new treatments and potential cures all the time. They have passed safety tests, and some show promise during clinical trials but are still years or even decades away from final approval. For someone with only months to live, that’s too long. The treatments could literally save their life. And yet the law prevents them from accessing what could be their last hope.

About 70 percent of Americans agree that terminally ill patients should have the freedom to try these experimental treatments that could save their life.49 Even so, for many years, partisanship prevented action. Democrats didn’t want to give Republicans a policy win, and Republicans benefited from the gridlock.

That changed once the American people got involved. One way they did was through the story of a man named Matt Bellina, a U.S. Navy pilot with a young family.50 He was diagnosed with ALS, which gradually robbed him of his ability to move, eat, speak, and breathe. His only chance to survive and stay with his family beyond a few years was to get access to promising treatments still under development. Our philanthropic community helped tell Matt’s story—a clear example of the injustice that resulted from extreme partisanship.

As more Americans learned of the issue and spoke up, politicians took note. Where previously inaction was in their interest, this bottom-up pressure showed elected officials that they needed to act. The groundswell of support pushed long-stalled legislation across the finish line in mid-2018.51 It empowered people like Matt Bellina in a major way.

The final law bore Matt’s name. Matt and his wife, Caitlin, wrote me a note that I’ll never forget. They said, “We know the right to try law would never have succeeded without your involvement. We are forever grateful for the hope you have given our family and all Americans.” As I write this, he is undergoing experimental treatment that may yet extend his life.52

Kicking off Stand Together’s semi-annual summit. These events bring together hundreds of business leaders, philanthropists, and social entrepreneurs. (2017, Colorado)

TRANSFORMING GOVERNMENT

Look closely at these three examples—criminal justice reform, veterans’ healthcare reform, and Right to Try—and you’ll see a road map to bottom-up transformation. They are the same three steps you’ve encountered in the previous three chapters. If you’re a Social Entrepreneur who’s passionate about public policy, this is where you’ll find a better way.

First, find what works and support it.

In this context, that means finding people who share your passion and are willing to work with you, even if you disagree on other issues. Have their backs when the partisans attack and ask them to have yours. If you choose your partners based on the “R” or “D” next to their name, you’re limiting your chances of success. Remember Frederick Douglass’s wise advice to “unite with anybody to do right.”

Second, celebrate success.

Partnership unites people who, under a tribal mentality, would be enemies instead of allies. This is progress by itself. Highlighting how your differences don’t prevent you from uniting will inspire others to do the same. They see that they can work together even with those they greatly disagree with on other issues.

Remember Frederick Douglass’s wise advice to “unite with anybody to do right.”

Finally, topple the barriers.

The more people get involved, the more others will want to get involved, and the more politicians will rise to the occasion. Elected officials in both parties will realize that voters want results, not more partisan wrangling, and that doing the right thing will help them politically. Their electoral interests will finally align with the interests of the American people. When good policy becomes good politics, we can expect politicians to finally do the right thing and empower people instead of holding them back.

Transforming the institution of government isn’t that far off. Every policy victory that comes from partnership will help shift the parties themselves. Right now, the parties are inclined toward ever-worse extremism and control. They will continue down that path until enough people demand a different approach on more and more societal problems.

No problem is intractable. No injustice is impossible to end. Is there a destructive policy that motivates you? A wrong you want to right, people you want to help? You can try to do so by pulling others down in a tribal, partisan way, even though that approach is already tearing America apart. Or you can give partnership a go. You’ll be amazed at the allies you attract, what you accomplish, the people you empower. And, like me, you’ll wish you’d taken this path all along.

In the build-up to criminal justice reform, my philanthropic community worked with a man named Van Jones. A former political appointee under President Obama, Van once organized a protest outside a conference I hosted. He disagreed—and still does—with many of the causes I support. I’m critical of his point of view on a number of issues.

As we came to see, none of our disagreements were as important as the area where we agreed. We shared a desire to remove the injustices in the criminal justice system. Once we realized this, we began working together.

After the First Step Act passed, Van participated in a video with Mark Holden, Koch Industries’ longtime general counsel and a committed leader for criminal justice reform. Standing side-by-side with Mark, Van said, “You got awesome people, and beautiful people, on both sides who don’t know what to do together, and if we start working on that, a lot of this stuff is going to get better.”53

Then he said words I will never forget: “We started working together to get some other people free, but the reality is, those of us who worked on this, we got some freedom.” That freedom, he says, should enable us all “to see the country differently and do more good.” Van’s words ring true. I intend to keep following this wisdom. For the sake of America, I hope you do too.