1.

BUSY BEING BORN

“He not busy being born is busy dying.”

BOB DYLAN1

For me, Bob Dylan deserved the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature. He has a special way of expressing some of the most important facets of human life. The quote at left—from Dylan’s song “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)”—gets at the heart of one of my guiding beliefs: success in life mostly depends on discovering your particular talents, then developing and applying them. The moment you stop moving forward, for whatever reason, you start falling behind.

That’s something I know from personal experience. Now, let me tell you what I don’t know.

I have no clue what your unique talents are. Nor can I tell you which path to follow—that’s unique too. In the pages ahead, I don’t have all the answers, or even most of them. But I do believe that everyone has a special gift that can be used to bring them fulfillment by helping others.

This idea has animated the better part of my life, now more than eight and a half decades long. My hope is that my journey—and the lessons I’ve learned along the way—may awaken you to the joy that comes from understanding yourself and contributing to the world around you.

Every journey must start somewhere, and that somewhere is self-discovery. Mozart began composing music when he was only five years old, but for the rest of us, unearthing our gifts usually happens much later and takes far longer. It certainly did for me.

I was fortunate to grow up in a family that gave me every opportunity to succeed. I recognize that I won the birth lottery, for which I will always be grateful. My parents did their best to give my three brothers and me a head start.

My mother, Mary, was a talented silversmith, enamelist, and artist dedicated to helping struggling artists and performers get started. She felt a deep obligation to assist everyone who reached out to her. She was the best possible exemplar of the biblical idea that “for unto whomsoever much is given, of him shall be much required.”2 I’m sure that’s one reason I came to demand so much of myself.

Every journey must start somewhere, and that somewhere is self-discovery.

My father, on the other hand, could be summarized by a different verse: “Spare the rod, spoil the child.”3

Fred Koch was a successful businessman, and he had no intention of letting his kids become “country club bums.” He was, for good reason, especially focused on me. When I was six, he started putting me to work doing all kinds of manual labor around our farm. It involved digging up dandelions and feeding animals, graduating to milking cows, shoveling manure, baling hay, digging postholes, and mending fences. I was often doing my farm chores within earshot of my friends, who were across the street yelling and splashing at the local swimming pool.

So went my afternoons after school, weekends, and summer vacations, year after year.

When I was 15, I spent the summer working at a line camp on a Montana ranch. My bunkmate was Bitterroot Bob, a volatile cowboy. Bitterroot bragged about his dishonorable discharge from the military during World War II for running from the line of fire. Some nights he would fire his revolver through the roof of our log cabin. When it rained, he’d get wet, but that didn’t seem to deter him.

Most mornings, Bitterroot and I would ride out to fix fences and bring back bulls that had hoof rot. We started out at sunrise and usually put in at least a 14-hour day. It was one of the grittiest, most challenging work experiences I had as a teenager. It was also one of the most memorable.

When my father died, I discovered a letter in his safety deposit box, in which he told his sons that “adversity is a blessing in disguise and is certainly the greatest character builder.” In retrospect, my father gave me many opportunities for character building. I now know that my father did me a hell of a favor. He wanted to keep me from having a feeling of entitlement and help me gain an understanding of what it means to be productive. As far as he was concerned, the earlier I learned this lesson, the better.

Research backs him up. Studies show that after age 30, your character and work habits are very hard to change.4 Fred Koch would have argued that 30 is 24 years too late.

His manual labor regimen helped instill in me a strong work ethic—an essential element of my later success. My parents also made a point of teaching their sons the values of integrity, humility, courage, perseverance, and treating others with respect. Crucially, Fred and Mary Koch practiced these values in their own lives, showing us more by their example than their words.

Although that’s not to say I actually learned the lessons at the time. Whether it was about a lecture over the dinner table or a day of digging postholes in a pasture, mostly I just grumbled—and rebelled. It didn’t matter whether I was ignoring his instructions or—when I was older—sneaking out to bars with a fake ID. My father’s answer was the same: get up early and work.

TRIAL AND ERROR—AND ERROR

Working at such manual labor also helped me understand where I don’t excel, which is pretty much in anything that involves using my hands. Realizations like this are crucial for every person. As you try to develop skills, you’re going to find a lot of areas where you just don’t have the necessary aptitude. Trial and error is a principle on its own, and in my decades of experience, there’s no such thing as too much error. Every dead end gives you a better sense of your best path.

REMEMBERING MY FATHER

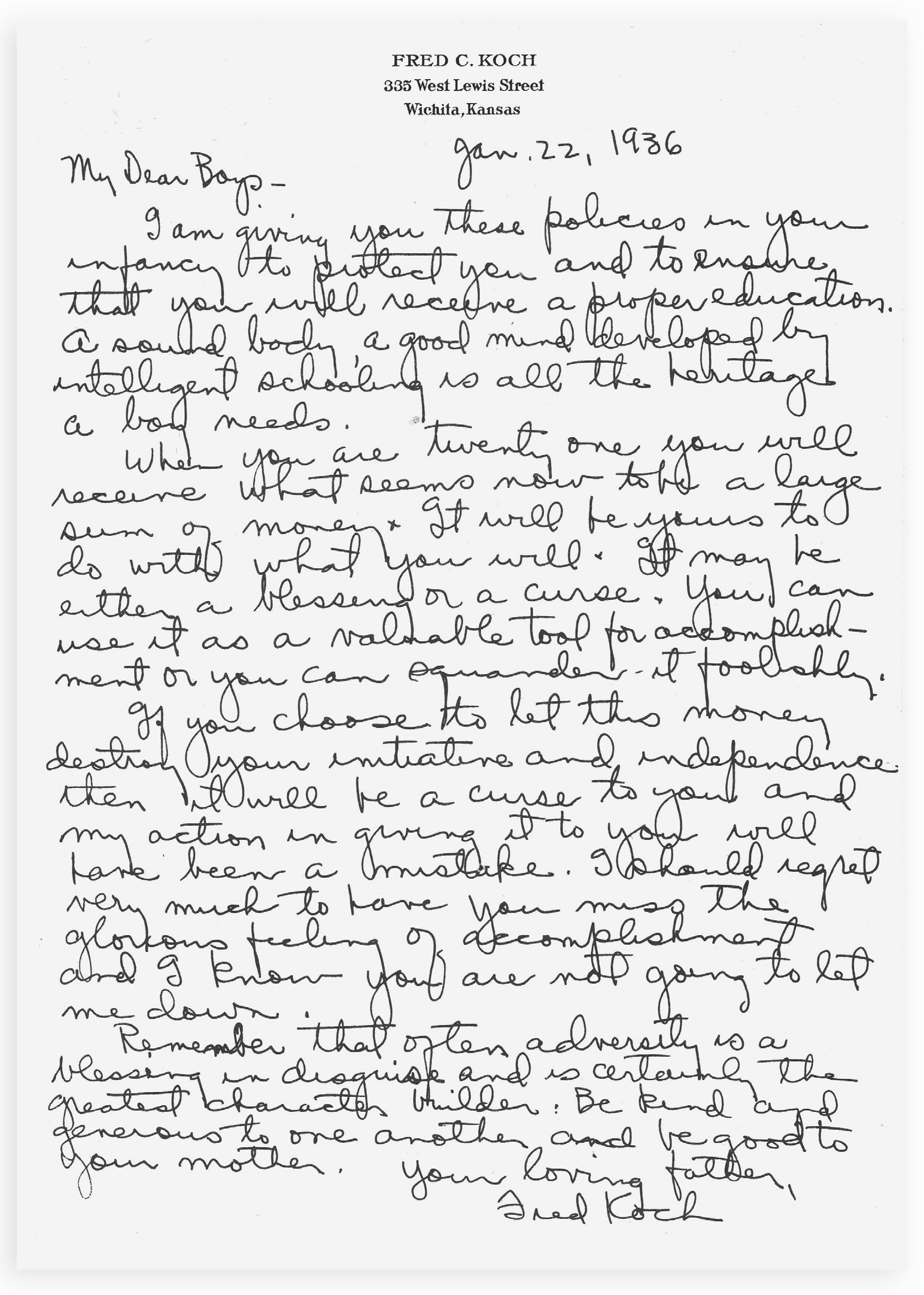

AFTER MY FATHER DIED, one of my responsibilities was to inventory his personal items, including those in his safety-deposit box. Not knowing what was in it, I drove to the bank and, with the area manager, opened the box, wondering what would be there.

What I found, along with a copy of his will and several valuables, was a letter. It was addressed to me and my older brother, my father having written it in 1936, shortly after I was born and well before our twin brothers came along. While the letter was more than 30 years old, in a way it contained my father’s parting words.

Although I’ve frequently referenced the part about the “glorious feeling of accomplishment,” that is far from the only line that has stuck with me.

Papa, as we called him, wrote that a “sound body” and a “good mind” are all the heritage a child needs. To that end, he left insurance policies, worth about $100,000 each, to help pay for our education.

He advised that we could use the money as a “valuable tool for accomplishment” or “squander it foolishly.” As he put it, “If you choose to let this money destroy your independence and initiative, it will be a curse.”

The letter ended by urging us to “be generous to one another and be good to your mother”—a piece of advice we could all hope to live up to.

Reading the letter touched me deeply. This was about as emotionally open as Fred Koch got. He came from a different generation that was very reserved. This was compounded by his stern upbringing without much outward affection in his first-generation Dutch immigrant family.

Of course, I never doubted for a moment that he loved us. He showed his love mainly by teaching values and through strict discipline. For him, raising us right was the most important thing.

To his credit, my father never prescribed a set path for his sons. Instead, he sought to instill in us the character and principles that would enable us to succeed no matter what we chose to do.

The messages in the letter I found after my father’s death are with me always.

He also practiced what he preached. For a young man trying to find my way in the world, few things impressed me more than his integrity, treatment of others, and commitment to learning. And, of course, his courage, which he expressed in one of his favorite sayings: “Don’t take counsel of your fears.”

While my wife, Liz, and I didn’t agree with many aspects of his particular method of parenting, we did agree with his emphasis on values. We worked hard to instill them in our children, Elizabeth and Chase, and whatever our shortcomings, we were successful in that. We couldn’t be more proud of our children, who they have become, and our relationships with them.

Raising my own children was well in the future when I first read my father’s letter in 1967. Standing there, I realized I was holding in my hands something I would always treasure. My father’s letter has been framed in my office ever since. Its message is with me always.

—CHARLES KOCH

My grandfather, Harry Koch, immigrated from the Netherlands in 1888. The three of us were at my father’s Kansas ranch in 1942.

Although my father could be stern, he had a great sense of humor. (Wichita office, 1958)

My father didn’t want his sons to become “country club bums,” so he put me to work starting at age six.

My father embodied that principle better than most. We lived on an experimental farm—not a commercial one—on the outskirts of Wichita, where my father kept cows, horses, dogs, and chickens. He liked to refer to himself as a “half-baked chemist,” and he loved to try his hand at finding new and improved ways to do things. “I figured out that we can live on $100 worth of food a year,” he announced one day. “There are mixes of beans that provide all the nutrients we need, so that’s all we’re going to eat.” Mercifully, that experiment didn’t last long.

Another time, he created a concoction called “Tiger’s Milk,” made of buttermilk, orange juice, yeast, and worse, which he forced me to drink. It tasted even more disgusting than it sounds. Aside from enjoying a good laugh about my father’s experiments now, the main thing I learned from them was that to find out what works, you first have to discover what doesn’t.

Fred Koch was also living proof that learning is a lifelong pursuit. He regularly reminded me, “Learn all you can, son, because you never know when it will come in handy.” I belatedly internalized that philosophy. I’m 85 and still trying to learn everything I can, every day and every hour.

Through all my early experiences, I was striving (sometimes unintentionally) to better understand my gift and how to apply it in a way that enabled me to contribute and succeed. It was a long struggle because I was mainly engaged in things I couldn’t do well and disliked doing.

One of the earliest clues about my aptitudes came in third grade. The subject was something that many struggle with: math. One day, as my teacher wrote problems on the blackboard, I noticed that, while the answers were obvious to me, they weren’t to any of my classmates. Although I didn’t end up becoming a mathematician, it gave me some confidence and a sense of direction.

At that time, my intellectual curiosity still lay dormant. My nonconformist tendencies dominated, leading my parents to send me to eight different schools before college. My adolescent contrarianism peaked as a junior in high school at Culver Military Academy in Indiana. My parents sent me there for discipline, which I proved I needed after getting caught drinking with other cadets on the train back to school after spring break. We were all expelled the next day.

I vividly remember the fear I felt as I faced my father after an all-night train ride back to Wichita. His first words were, “Well, I see you made it, boy.” His disappointment was obvious and penetrating. His next words terrified me: “I’ve been trying to decide what to do with you.”

The punishment made it even clearer just how unhappy he was. He shipped me off to live with my uncle Anton, to complete my junior year in Quanah, Texas.

I’ll say this much for Quanah: it was during my time there that I had a mind-set shift about school. The contrast between my aptitude for math and abstract concepts versus other subjects was becoming more apparent. In addition, as I was grounded for most of my stay and had few distractions beyond my job shoveling wheat in a grain elevator, I actually became diligent about doing homework. After finishing the school year in Texas, I was readmitted to Culver by agreeing to repeat the spring semester at summer school.

My experiences and unhappiness helped me begin to realize that I needed to change my life. I was learning that fulfillment doesn’t come from instant gratification. I tried plenty of that, including, but not limited to, sneaking out with my friends to get drunk starting at age 14. Sure, it gave me a temporary mental reprieve from the things I didn’t like—my father’s tasks, bullies at school, boredom and confusion—but it didn’t give me lasting pleasure. Aristotle wrote that “one swallow does not make a spring,” and so it was with the passing fun I got from making dumb decisions.5

Finally, by the end of adolescence, I grasped that fulfillment comes from a much broader horizon. I could either do the hard work of applying myself and reach long-term success, or continue to pursue destructive instant gratification. This is the principle of “time preference.” The higher your time preference, the more willing you are to sacrifice the future to get what you want now. The lower your time preference, the more you are willing to forgo gratification now in order to bring about a better future.

As this realization took root, I picked up an interest in reading—thanks to William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, and George Orwell—and began to have some academic success. It was just enough to get me admitted to a good university: the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Both my parents and I were relieved: me, because I finally felt a sense of freedom; them, because I hadn’t completely squandered the future they had worked so hard to give me.

A FULL-TIME NERD

I liked MIT because it spoke my language: math. It had been a full decade since my first inkling in third grade, but gaining a little maturity and success in school convinced me to keep at it. I still had little idea where I could succeed, so I followed my father’s example and began to experiment, taking as many math and other abstract-concept-focused courses as possible.

At first I thought I wanted to major in chemical engineering. I quickly quit that track because it involved too much memorization. Next I settled on geology, which involved even more memory work—too many rocks. So I dropped that and signed up for courses I thought I would enjoy and do well in, such as the full range of physics, math, and thermodynamics. I was turning into a real nerd.

It became apparent to me that many scientific principles can be more broadly applied, including to individuals, organizations, and society. I was especially fascinated by the second law of thermodynamics, which holds that entropy virtually always increases in a closed system. Entropy is a measure of disorder or uselessness. In lay terms, this means that progress stalls or declines when something is walled off from the outside world.

Usually you hear this concept in discussion of technology, but it applies to every facet of life. People, as well as organizations, stagnate when they aren’t open to new ideas or fail to experiment or learn new skills. Countries crumble when they shut the door to trade, immigration, and innovation. It was partially in the second law of thermodynamics that I came to see the principles of openness and exchange and their importance to progress.

People, as well as organizations, stagnate when they aren’t open to new ideas or fail to experiment or learn new skills.

Such realizations, while interesting to me, did not constitute a path to graduation. My scattershot academic approach kept me from satisfying the requirements for a degree in a specific field, so I defaulted to general engineering. In the first two years, my performance was less than stellar, given the temptations of Boston and the freedom MIT offered. But that radically changed after my sophomore year, when my father threatened to stop paying my tuition unless I fully applied myself. That reality finally got through my thick skull, causing my grades to improve a full point.

During the summer, outside the classroom, I had some of my most valuable educational experiences. I worked on a geophysical crew for an oil exploration entrepreneur in Oklahoma, in the engineering department at Chrysler in Detroit, and for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (now Exxon) at their Bayway, New Jersey, refinery.

While working in Oklahoma, I was driving a water truck when its injection pump got low on oil. My response to the situation backfired: I accidentally added too much oil, creating an even bigger problem. It was one of the many signs that I’m better at understanding engineering concepts than operating things.

At long last, my abilities (and lack thereof) were becoming clear to me. It wasn’t exactly engineering. And it definitely wasn’t motor repair. I was best at—and found the most fulfillment in—understanding and applying abstract principles. It wasn’t wrestling with abstract theories, like a philosopher or a professor. It was grasping them in a way that would enable me to productively apply them, with the goal being to solve concrete problems.

I wish there had been an “aha!” moment when all this became apparent to me. In fact, it took me a long time to articulate my skill-set, and I’m still refining that understanding—it’s a lifelong journey. Years later, I discovered the work of psychologist Howard Gardner, who developed the theory of “multiple intelligences.”6 I fall into the category of people he described as having “logical-mathematical intelligence.”

The more important lesson I took from Gardner—as well as from his critics—is that people, by and large, are neither smart nor stupid. We are all both, at the same time: smart in some ways, stupid in others. We are smartest when we discover, develop, and apply our unique strengths—whatever they may be—and dumbest when we don’t. There’s an old joke that says you’re unique … just like everyone else. And it’s true: everyone has something special to contribute to the world around them.

This points to another important truth I slowly learned: partnership is essential to progress. One person’s strengths compensate for another person’s weaknesses, and vice versa. As you join with others who share your vision and values, you will accomplish much more, much faster. The possibilities are limitless in a community where people work together to realize their unique potential and help others do the same.

At the end of my undergraduate years, that discovery was still a long way off for me. I only knew that I wanted to use my aptitude for complex concepts to achieve something positive in the real world. So I took a master’s degree in nuclear engineering because it seemed ripe with opportunity.

Nuclear engineering also appealed to my interest in abstract ideas: few engineering fields are more conceptual. In the 1950s, nuclear energy was in its early stages, so it seemed that it would offer plenty of entrepreneurial opportunities. It didn’t take me long to see it offered little of the sort. Nuclear energy is so regulated that entrepreneurship and innovation are all but impossible. (Witness the decades-long construction of new plants, the massive cost overruns making them uneconomic, and the resulting dearth of new projects—which is tragic given the technology’s potential, especially today, when zero-emissions energy is in high demand.)

Given that nuclear appeared to be a dead end, I thought chemical engineering might better meet my abilities and entrepreneurial interests. While pursuing that master’s degree, I considered going even further and getting a doctorate in chemical engineering, since I was handling its abstract concepts well.

My first step was to get my department head’s opinion on the subject. Fortunately, he had a clear-eyed view on the matter and asked me, “What do you want to do?” I told him I wanted to be an entrepreneur. His response was blunt: “Then get the hell out of here. We’ll just make your life miserable for nothing.” I didn’t need another nudge.

My next step was to find a job that would enable me to experiment. I wanted to find the kind of work that fit my aptitudes and would give me the best chance of finding success through entrepreneurship. I landed one at the consulting firm Arthur D. Little, which was in Boston and covered a wide range of disciplines.

I approached the job as one giant experiment, starting in product development, which wasn’t a great match. I moved to a job in process development, where I could make a better contribution. This became a stepping-stone into management services, where I consulted on innovation and business strategy. This was by far the best fit, and it helped prepare me for a career as an entrepreneur.

The final confirmation that I was on the right path came via a graduate course in finance that the firm allowed me to take at MIT during the 1961 spring semester. The coursework came easily to me, and I found it enjoyable and fulfilling. Combined with the hands-on experience I was gaining at Arthur D. Little, the course helped me begin to understand that success in business depends on empowering employees to succeed by contributing.

I would later come to see that thriving communities and nations depend on the same principles—just replace “business” with “society” and “employees” with “everyone.” That is, success in society depends on empowering everyone to contribute.

At this point I was consumed by the desire to become an entrepreneur. I hounded friends and professors at MIT about start-ups that I could get involved with. In fact, after moving back to Wichita to work in the family business, we did invest in several such opportunities. One was an innovative communications system developed by a former roommate. Another was with Ray Baddour, the chairman of the chemical engineering department, who had started what is now Koch Separation Solutions.

A SUDDEN SHIFT

What changed my direction and my life was two phone calls in 1961.

The first was in the summer. My father called and asked me to come back to Wichita to work with him. I turned him down. Given how tough he had been on me growing up, I didn’t think I would have the opportunity to experiment and try new things. One of his favorite sayings, having strong Dutch ancestry, was, “You can tell the Dutch, but you can’t tell them much.” For Fred Koch, this was less of a joke than a statement of fact, especially in dealing with me.

A month later he called again, saying, “Son, my health is poor, and I don’t have much longer to live. Either you come back to run the company, or I’ll have to sell it.” His blood pressure was nearly twice as high as it should have been, even with medication. He assured me that I could run Koch Engineering—a small, struggling equipment company—however I wanted. He also indicated that he wanted me to run our main business once I was ready. For a 25-year-old wanting an entrepreneurial opportunity, this was as good as it was going to get.

I accepted. I’ve been here ever since.

Whatever I’ve achieved in the intervening years is the result of what preceded it. For the previous 20 years, I had been on the long journey to discover, develop, and apply my talents, as well as develop the values required for long-term success. It happened in fits and starts, sometimes despite my best efforts to undermine it. But it happened nevertheless.

I was starting to see that personal success and fulfillment—in any field or endeavor—comes from helping others in a way that is mutually beneficial. Alexis de Tocqueville called this acting out of an “enlightened regard for [oneself],” which “constantly prompts [people] to assist one another.”7

Tocqueville’s wisdom points to one of the most important principles I ever learned: being “contribution motivated.” This is a concept derived from the psychologist Abraham Maslow, one of the biggest influences on my life. He argued that individuals are motivated by the desire to meet our most basic needs: food, shelter, sleep, and so on.8 Beyond that, we crave emotional security, friendship, community, and intimacy, as well as a sense of worth and self-esteem, among other things.

When we seriously lack any of these, we tend to be driven by the deficiency. (I call this being “negatively motivated.”) In this state, people tend to act in unhelpful, even dangerous, ways—often understandably so. But when we satisfy these needs, we can begin to realize our potential and find fulfillment in our lives. Something remarkable then begins to occur.

Up to that point, selfishness and unselfishness struggle to coexist. After all, if you are hungry or homeless, it’s highly unlikely you’ll give up food or shelter for the sake of someone else. Once such needs are met, however, your natural desire to help yourself becomes entwined with helping others, making it easier to become contribution motivated. Your success is tied to their success, and the more you contribute to the world around you, the more you tend to be rewarded, both internally and externally.

Maslow called this fusing of selfishness and unselfishness “synergy.” Once synergy happens, you become all that you are capable of becoming, using your gifts to help people in extraordinary ways. Maslow called it self-actualizing. While this looks different for everyone, it is the path by which anyone can find lasting, lifelong fulfillment.

I came to see this through my experiences as well as my studies, which took off once I was home. (More on this in the next chapter.) I also began to see that synergy is essential for the success of communities and countries. Maslow predicted it would be possible for a society to form in which people who pursue their own self-interest “automatically benefit everyone else, whether [they] mean to or not.”9 This means that creating a better society requires helping many more people to become contribution motivated.

The good news is that most everyone practices this concept in at least parts of their lives, even if the theory is foreign. An electrician who enjoys serving his customers is contribution motivated. So is a professor who likes teaching her students how to unlock their abilities, or an artist whose painting evokes a sense of wonder in those who see it. Someone who devotes time or treasure to a charitable cause also fits the bill—they gain fulfillment by helping others.

It’s even possible for people who lack their basic needs to become contribution motivated. No one illustrates this more powerfully than Viktor Frankl, whom I discovered many years ago. He developed an entire school of psychiatric thought—“logotherapy”—dedicated to helping people discover what gives them joy and fulfillment.10

Frankl has influenced me in several ways.

In terms of theory, Frankl reinforced my belief that every individual, no matter the obstacles, can find meaning in their lives by contributing to the lives of others.

What’s even more important to me than his powerful work are the lessons from his actual life—his actions during the series of tragic events that he endured while developing his theories.

You see, Frankl was Jewish and had the great misfortune of living in Austria during the 1930s and 1940s. After the Nazis annexed his country, Frankl found himself under the control of a regime that wanted to exterminate him because of who he was. The Nazis forced him into a ghetto and then shipped him and his family to Auschwitz. Yet even in a death camp, Frankl found a way to apply his unique abilities to help others.

The unspeakable suffering that surrounded him could not shake Frankl’s desire to contribute. He strived to help others in ways big and small, sharing what little he had with those in greater need. He used his psychiatric training to counsel people who had lost everything and everyone they loved. While some were turning on fellow victims to survive, Frankl did whatever he could to help. In doing so, he not only enabled others to discover meaning in their lives, he discovered meaning in his own.

By all accounts, having a purpose gave him the will to survive the most dire conditions, and his example did the same for a number of his fellow prisoners.11 In the darkness of Auschwitz, Viktor Frankl was a small yet blinding ray of light.

A VISION OF THE FUTURE

If everyone were contribution motivated, the result would be a society unrivaled by any in the history of the world. But the reverse is true as well: when people can’t contribute, society is significantly worse off.

If everyone were contribution motivated, the result would be a society unrivaled by any in the history of the world.

I was beginning to understand this by the time I came back to Wichita. My self-transformation was underway. The more I applied myself, the more success I found, and the more I wanted to contribute—a never-ending cycle that motivates me still. Ever since, a good day has been one in which I feel I have contributed. That drive is the main source of all the success and joy I’ve had, as it has resulted in my creating value for others, not just in business but more broadly as a Social Entrepreneur, helping others contribute.

Looking back, there’s no question that I started with big advantages. But as I hope to show in the pages ahead, even people who have nothing and face seemingly insurmountable obstacles can rise farther and faster than they ever dreamed.

The path for each of us is unique, but the elements are the same—discover and develop our unique gifts and use them to contribute to the betterment of others and ourselves. That’s the way I was heading when I came back to Wichita. I was trying to find a better path for my life and was about to discover one for business and society as well. And even now, at age 85, I’m still busy being born.