THREE

“LIKE A

BANKED

FIRE

. . . HOT

AND

FIERY

WITHIN

”

COLUMBIA

DURING

RECONSTRUCTION

, 1865–1877

Columbia’s post–Civil War recovery held different meanings depending on what a person stood to gain or lose. For most whites, the first step was chronicling what had been (and in many respects would continue to be) the greatest transformative event in the relatively young city’s history. For editor Julian Selby and writer William Gilmore Simms, wielding the pen proved a more successful defense for their vanquished city than any sword or firearm had during the last months of the war. Their accounts in the Columbia Phoenix

granted local Democrats the moral high ground by portraying the war solely as a conflict of Northern aggression and the precursor to years of Federal oppression.

A parallel narrative addressing the aspirations of both local Republicans, black and white, and newcomers to the area fell largely silent, squelched in the aftermath of Reconstruction’s demise in 1877. All citizens, new and old, historically free and most recently emancipated, strove to work out the implications of a Columbia without slavery in which generations-old social boundaries were no longer the law of the land. Meanwhile, new buildings reshaped the cityscape, trains reconnected Columbia to towns and cities near and far, and residents looked toward an uncertain future.

Nearly three decades later, Thomas Woodrow Wilson, a Columbia resident during Reconstruction and the future 28th president of the United States, offered an arguably accurate assessment of the postwar era. “It was like a banked fire . . . hot and fiery within.” With little agitation, the passions embroiled in the South’s social, economic, and physical rebuilding often burst into an angry fire of rhetoric, mutual blame, and ill will.

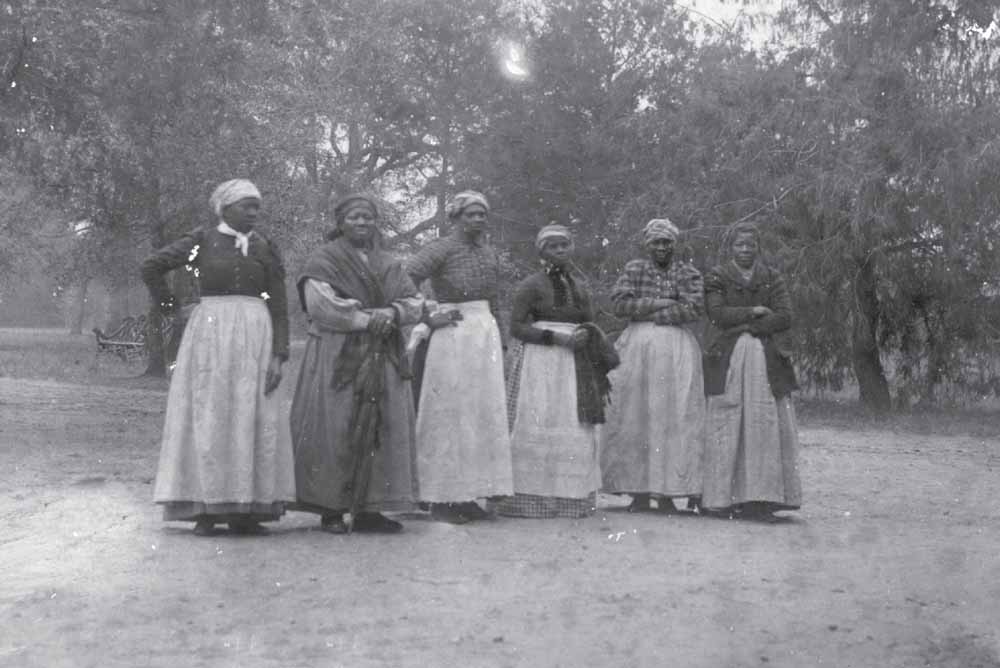

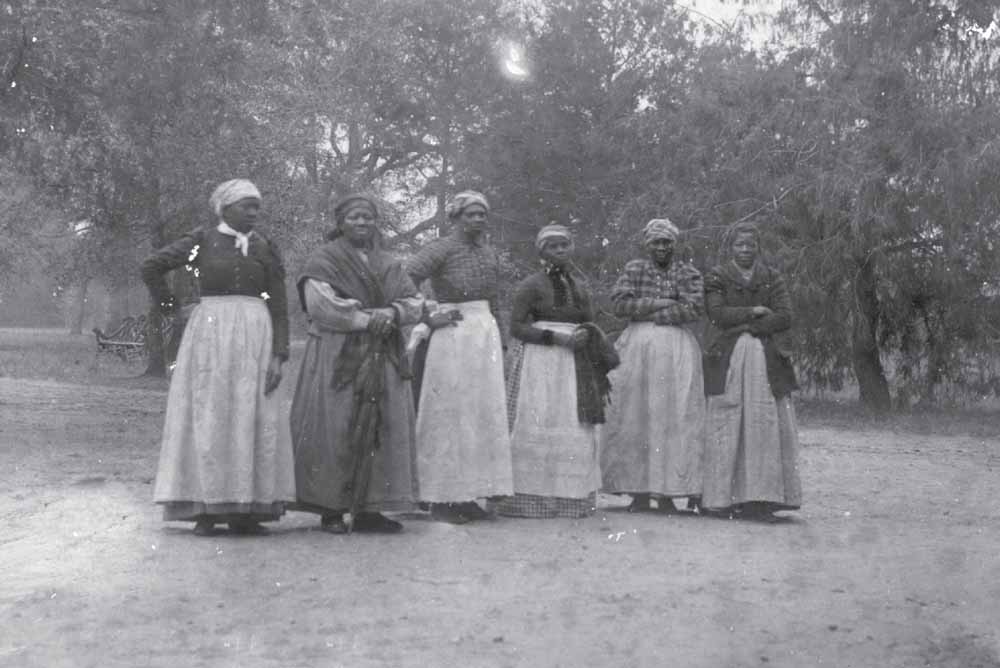

DOMESTIC

WORKERS, C

. 1865.

This photograph was among materials identified as having come from Columbia’s Hampton family, which was among the largest of the area’s planter-class slave-holders. Nothing else is known about these women. Neither their names nor the jobs they performed were recorded. However, based on their clothing, these women most likely were among the many domestic workers needed in running a large household. Demographically, during the antebellum and post–Civil War periods, African American women made up the largest percentage of people who cooked, cleaned, and cared for children. Upon gaining freedom, some formerly enslaved citizens left Columbia to forge a new life elsewhere, often performing, albeit for wages, the skilled and semiskilled jobs they held previously. Many of those who stayed to become tenant farmers found themselves living under conditions that bore a striking resemblance to slavery. (Historic Columbia archives.)

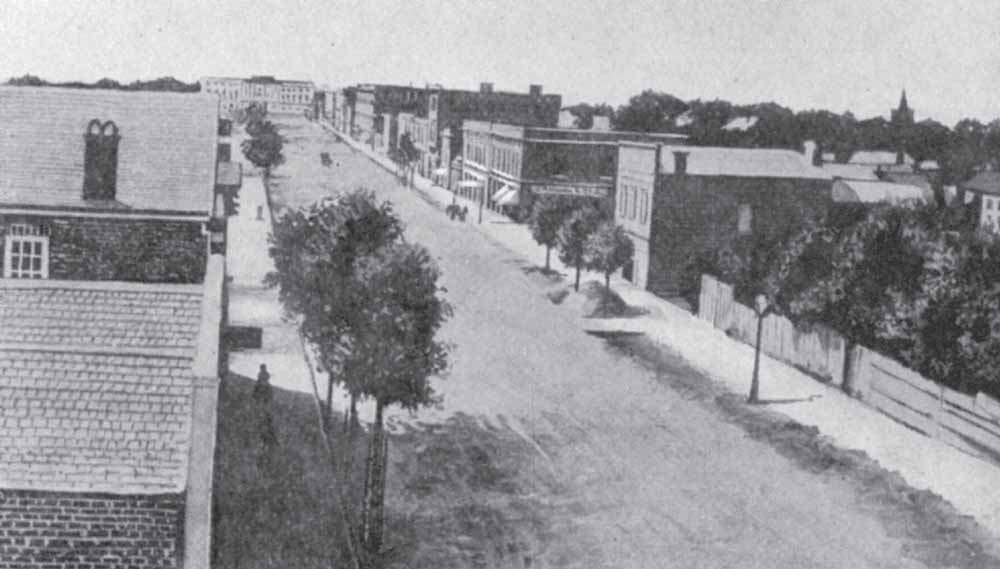

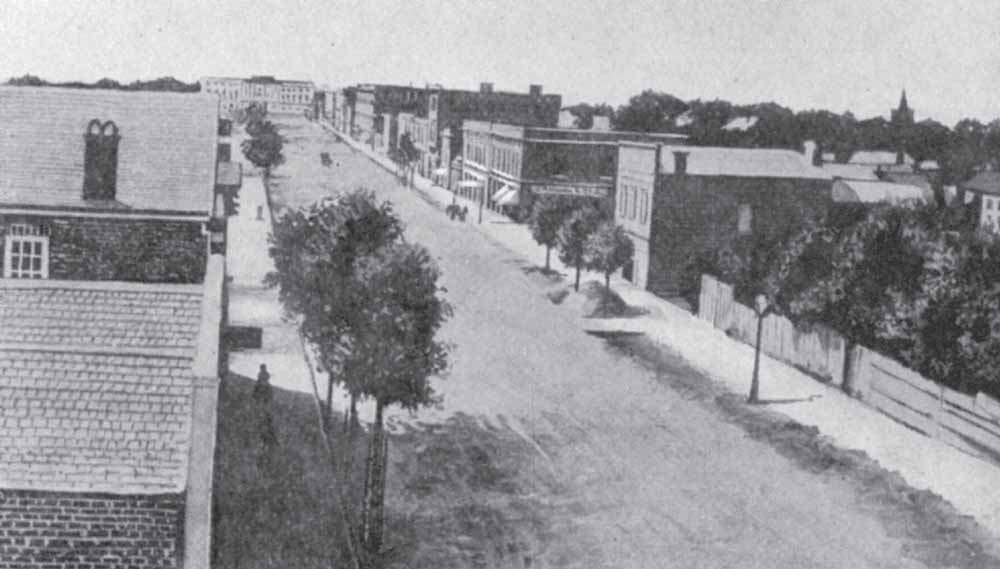

RICHARDSON

STREET

LOOKING

SOUTH

, 1869.

Four years after Columbia’s burning during the latter of months of the Civil War, South Carolina’s capital city had made reasonable progress rebuilding from the physical destruction it had suffered. Among the first areas to recover was Richardson (Main) Street, where many of the city’s stores, services, and offices were reestablished. The earliest photographic documentation of this transformation was included among images featured in a foldout postcard book created nearly 50 years later. Shot most likely from Plain (Hampton) Street looking south, this perspective shows freshly planted street trees, new masonry buildings, and the State House, still under construction. (South Carolina State Museum.)

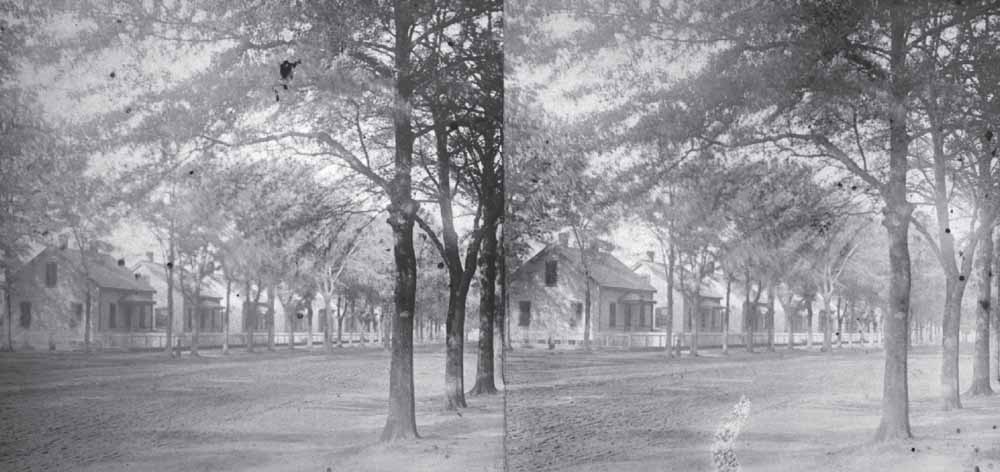

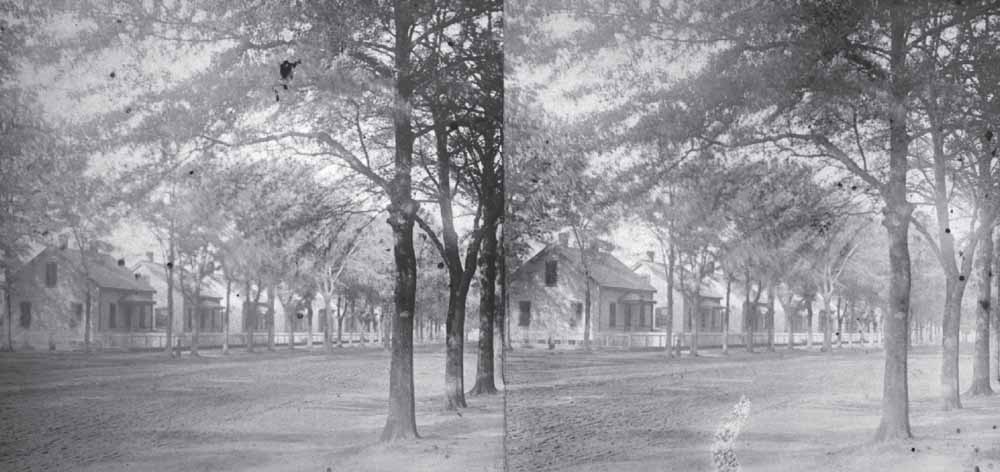

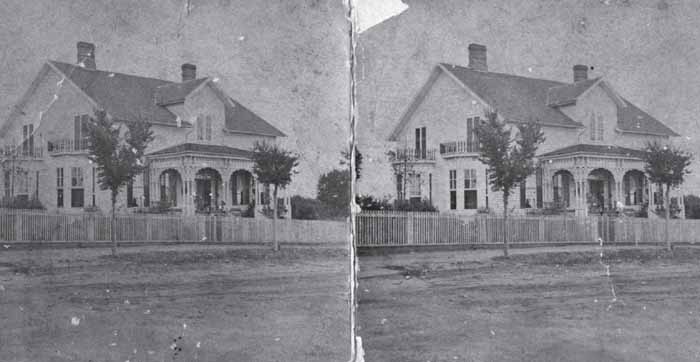

HURLEYVILLE

, 1873.

During the Reconstruction era, Columbia experienced unprecedented social and economic change as it shifted from a slavery-based to a wage labor–based society. Physical changes occurred, too, with new buildings replacing destroyed ones and supporting business and residential needs. Recognizing an opportunity to provide rental housing for laborers unable to buy property, state legislator Timothy Hurley built 24 modest cottages on land formerly part of the Hampton-Preston estate. Bounded by Laurel, Henderson, Blanding, and Barnwell Streets, “Hurleyville” was a whites-only community for blue-collar employees of the Charlotte and South Carolina Rail Road Company, located one block to the east. Local “photographist” Richard Wearn included the community in stereograph cards he produced in 1873 with partner William P. Hix. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2005.5.1.)

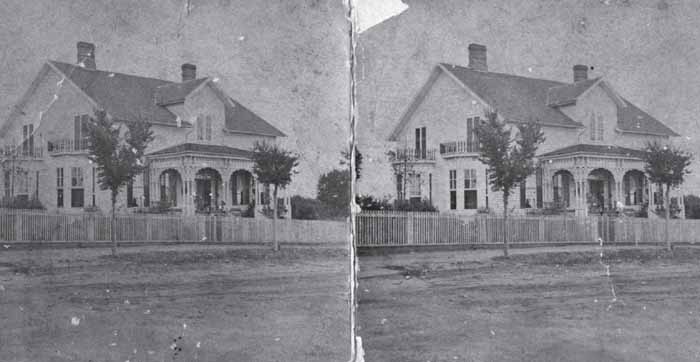

NASH

RESIDENCE

, 1873.

Reconstruction afforded African American men the unprecedented opportunity to be part of the political process, both by voting and holding public office. Political representation in South Carolina changed dramatically, with black men holding 75 of the 124 house of representatives seats and 10 of the 31 senate seats. Among those newly empowered black leaders was William Beverly Nash, a Virginia native formerly enslaved by Columbia’s Preston family. An entrepreneur with business interests in real estate, farming, and a brickyard, Nash represented Richland County from 1868 until 1877 and maintained a residence north of the federal courthouse and post office, within Laurel Street’s 1100 block. (South Carolina State Museum.)

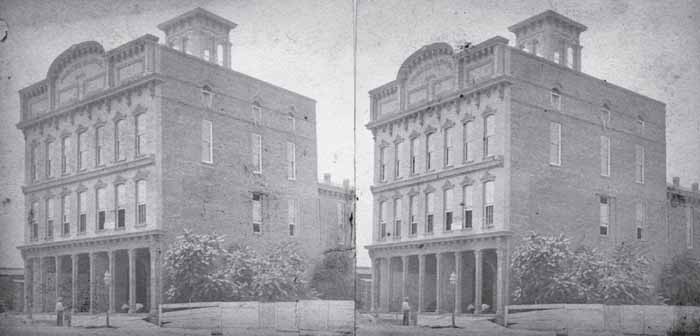

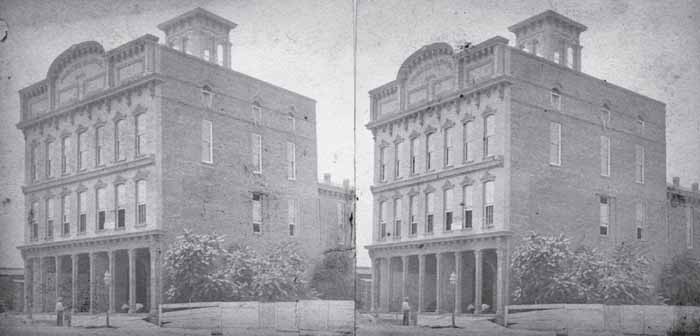

PARKER

BLOCK

, 1873.

One of the city’s more conspicuous additions during Reconstruction involved a three-story building erected for Niles G. Parker. Located immediately north of the State House grounds, in the 1200 block of Richardson (Main) Street, the Italianate-style structure drew criticism from Parker’s detractors, who asserted that the former state treasurer became wealthy by renting out rooms for committee meetings while drawing rent from its commercial offices and spaces for performances and meetings. Occasionally bearing the moniker of “Parker’s Haul” for these excesses, the building later became the administrative headquarters for the state’s agricultural affairs and dispensary system. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2005.8.3.)

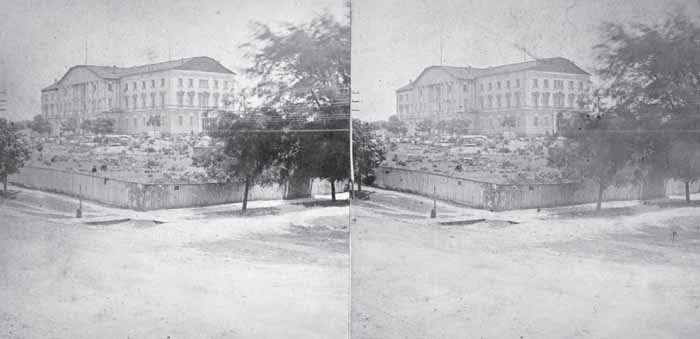

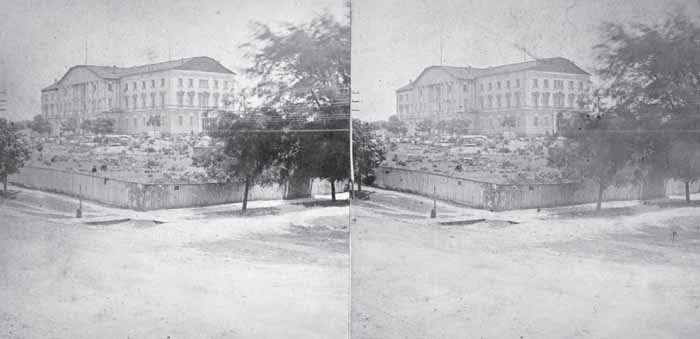

STATE

HOUSE

, 1873.

By the later years of the Reconstruction period, enough work had been performed on the South Carolina State House to render it usable by the government. Outfitted with a temporary roof, the building served its purpose, though it would be decades before the structure could be considered completed. Photographers Richard Wearn and William P. Hix produced a stereograph image of the site from its northwest perspective looking southeast toward the University of South Carolina. By that point, the grounds surrounding the State House were little more than untended acreage on which construction materials competed with grazing cows. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2005.8.2.)

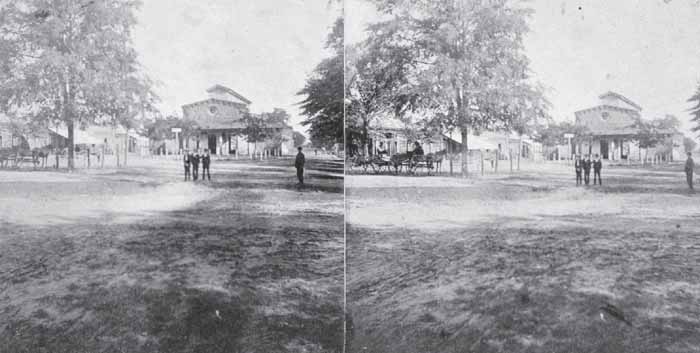

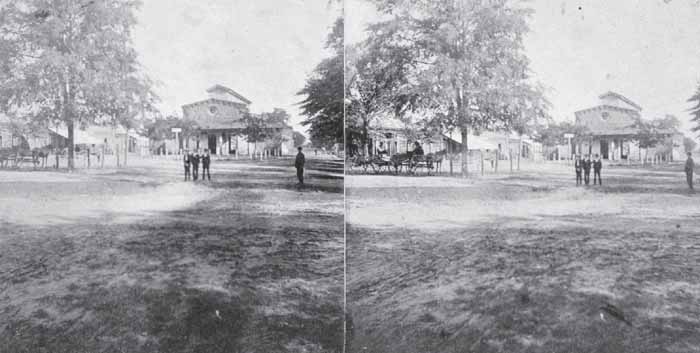

CITY

MARKET

, 1873.

While the fire of February 1865 consumed scores of buildings important to the daily lives of Columbians, destruction of the city hall and market within Richardson (Main) Street’s 1400 block proved especially poignant. By 1869, amid the city’s postwar rebuilding, a new public market was erected one block west. Here, a trio of boys poses for photographer Richard Wearn or William P. Hix, who documented the site in the 1400 block of Assembly Street a few years after its completion. Though destroyed in 1913, this downtown landmark set the precedent for further, far greater market construction on this main thoroughfare that lasted until 1951, when the state abandoned the then obsolete facilities for newer accommodations off Bluff Road. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2005.8.1.)

BERRY

FAMILY

RESIDENCE

, C. 1875.

Assembly Street’s 21st-century character bears little resemblance to its 18th- through mid-20th-century former self, where residences mixed with commercial, educational, and religious buildings on most blocks from Elmwood Avenue to well south of the State House. Perhaps no photograph better illustrates the corridor’s drastic transformation than one depicting cabinetmaker Milo Hoyt Berry and his family posing in front of their 1840s-era residence that overlooked St. Peter’s Catholic Church. Today, a parking deck looms where it and other houses once stood in the 1500 block of Assembly Street. (Berry descendants.)

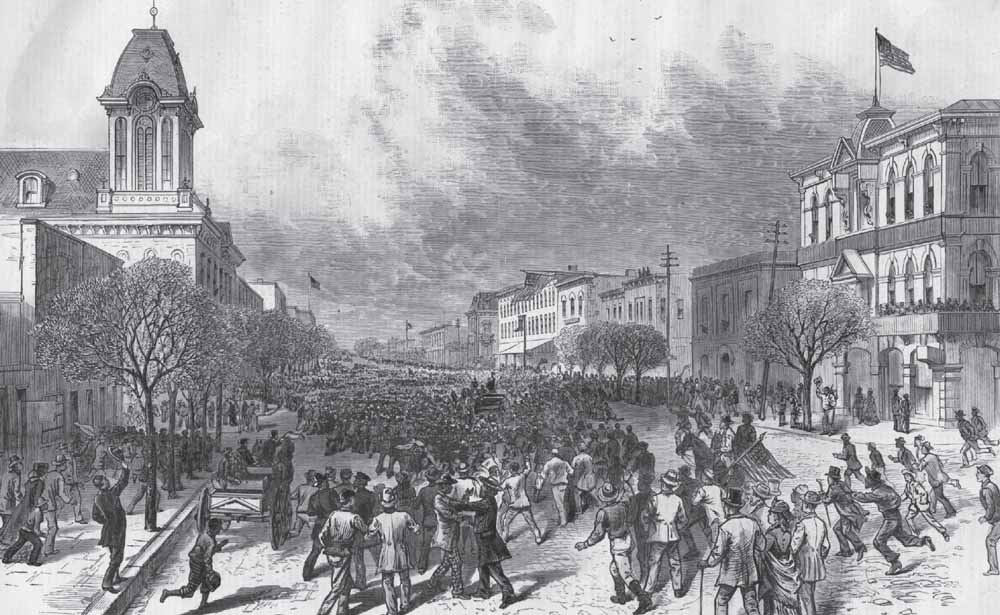

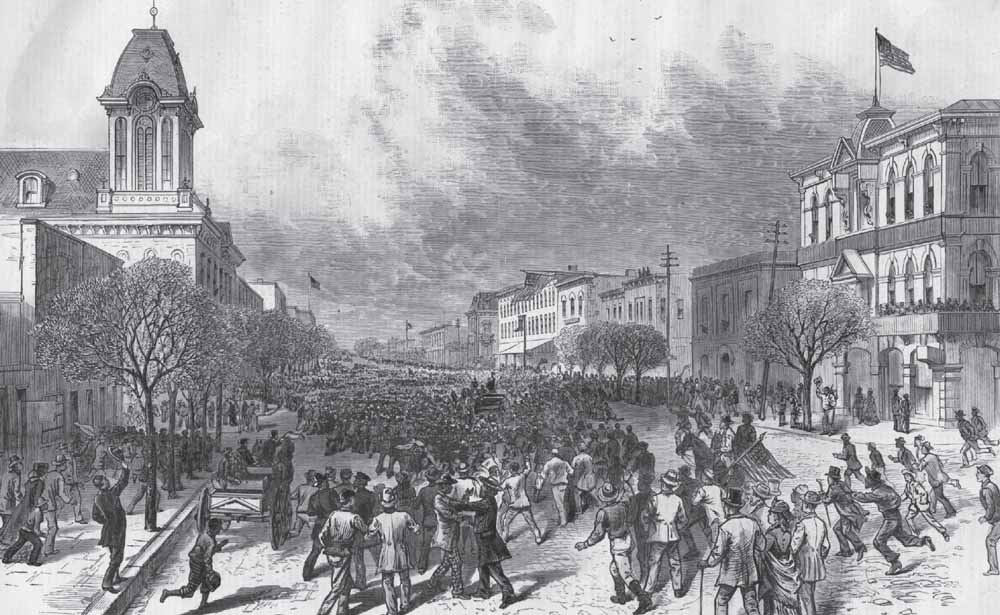

1400 BLOCK OF

MAIN

STREET

, 1877.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated

chronicled former Confederate general Wade Hampton III’s successful, though hotly contested, run for governor in 1877, an event that marked the end of Reconstruction in South Carolina. In doing so, the newspaper offered a rare glimpse of Columbia’s Richardson (Main) Street, as seen from its 1400 block looking north. Today, the only remaining landmark pictured in the illustration is what generations of citizens have known as Sylvan’s Jewelers, built in 1871 as the Central National Bank. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2005.15.3.)

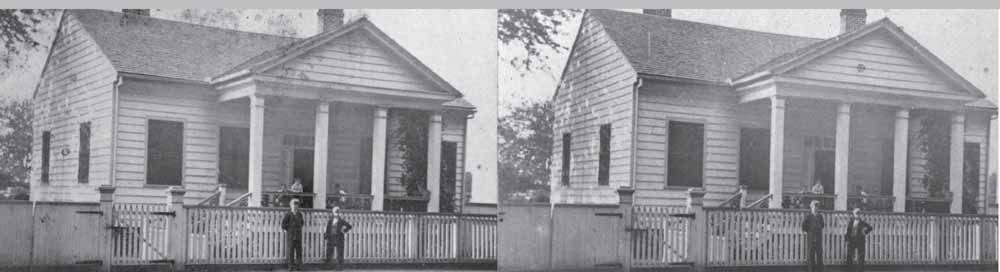

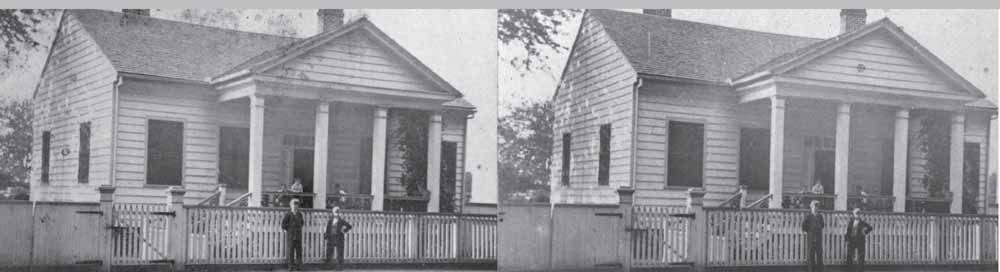

KING

RESIDENCE, C

. 1878.

Among the stereograph images published by photographer W.A. Reckling in his Popular Series of Southern Views

was this Greek Revival–style cottage that belonged to Robert King. Initially a master mechanic with the Charlotte, Columbia & Augusta Railroad Company, King was later a machinist with Shields Foundry, also known as the Palmetto Iron Works, located on Laurel Street, overlooking Sidney Park. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2014.13.1.)