FOUR

“BUSINESS, HEALTH,

AND

PLEASURE

”

CRAFTING

IDENTITY AND

LAYING

NEW

FOUNDATIONS

, 1877–1900

Growing in ways previously unknown, Columbia had taken increasingly greater steps toward becoming a modern city during the final years of the 19th century. Numbering 21,108 citizens by the end of the century, its population had grown by 127 percent since Reconstruction. New industry had developed, and mass transportation stretched beyond the city limits. At 12 stories, the first skyscraper dwarfed its neighbors and pierced an otherwise low skyline. Successful businessmen erected handsome sprawling residences downtown and in recently established suburbs to the north and southeast. For those who could afford them, creature comforts were plentiful with a host of stores—including some boasting telephone service—offering fine clothes, food, and specialty services.

Touting a healthful climate, inexpensive land, and an eager workforce, boosters represented Columbia as progressive, a city with “possibilities . . . practically unbounded.” Frequently, they noted its successful resurrection from war and devastation. Indeed, the symbolic phoenix was rarely missing, whether in private conversation or public endorsement, at least by those who were in power.

At the same time, others saw Columbia’s limitations and the undesirable by-products that modernization brought. Jim Crow laws codified and exacerbated generations-old racial, social, and political divisions between black and white citizens. Poor living conditions, particularly within the mill communities, raised health concerns. Streetscapes scarred by unkempt trees and refuse prompted activists to champion civic improvements, promote parks, maintain gardens, and take greater steps to preserve the city’s legacy of natural beauty.

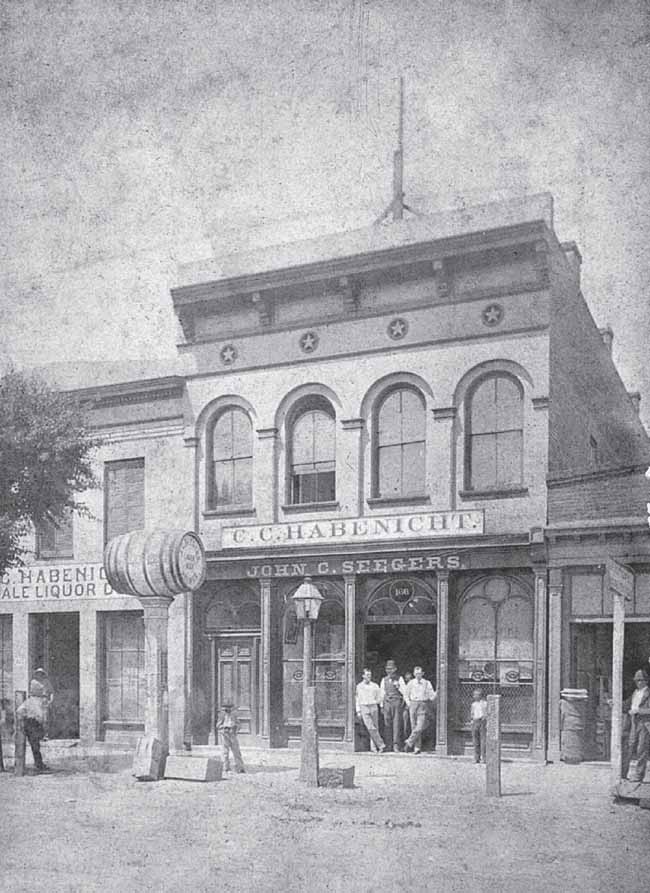

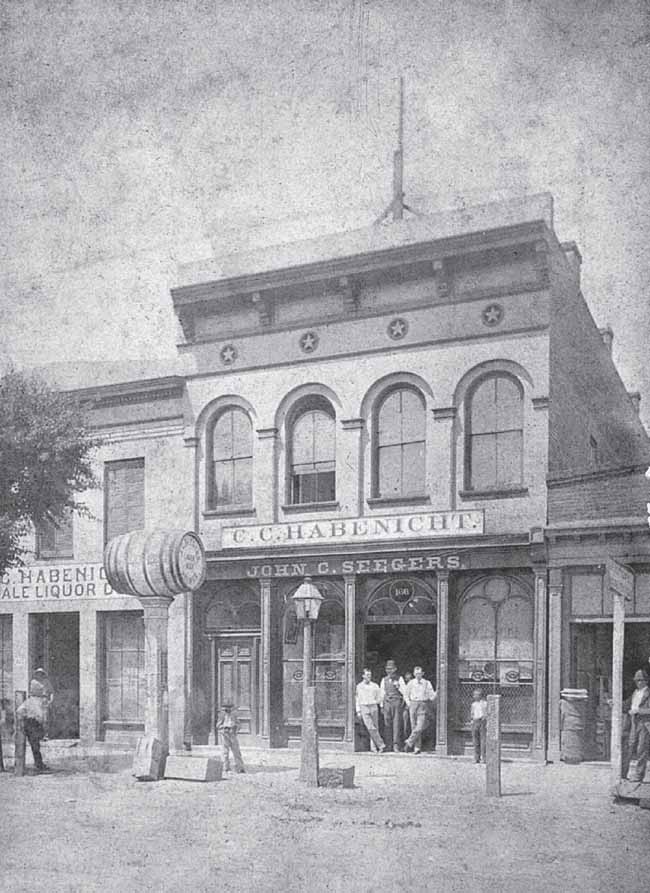

SEEGERS

-HABENICHT

BUILDING, C

. 1880.

John C. Seegers’s and Christopher C. Habenicht’s former saloon and brewery survives as quite possibly the earliest example of Columbia’s post–Civil War rebuilding. Completed by September 1865, the structure became an instant landmark among Richardson (Main) Street’s businesses. During the 1870s through the 1880s, it served as a meeting place for various organizations, including the Schuetzen Verein and Freundschaftsbund, German shooting and friendship societies. Later, the property, which became 1631 Main Street, was put to different uses, including as a sporting goods store. In 1937, the building’s original Italianate appearance received an Art Deco–inspired renovation similar to that seen today. (Lynn Boyd.)

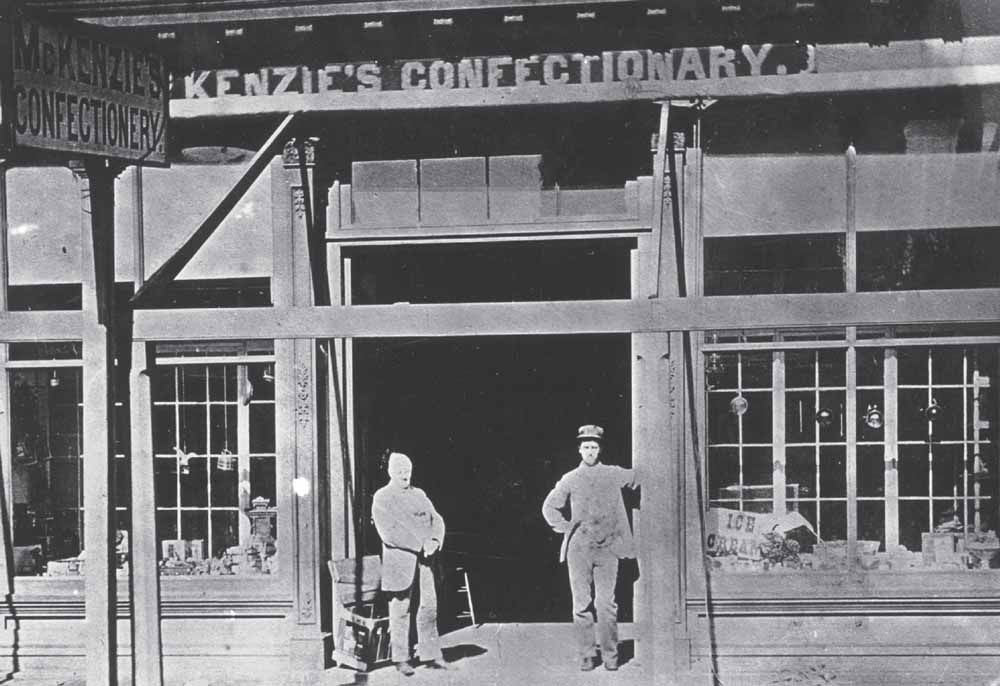

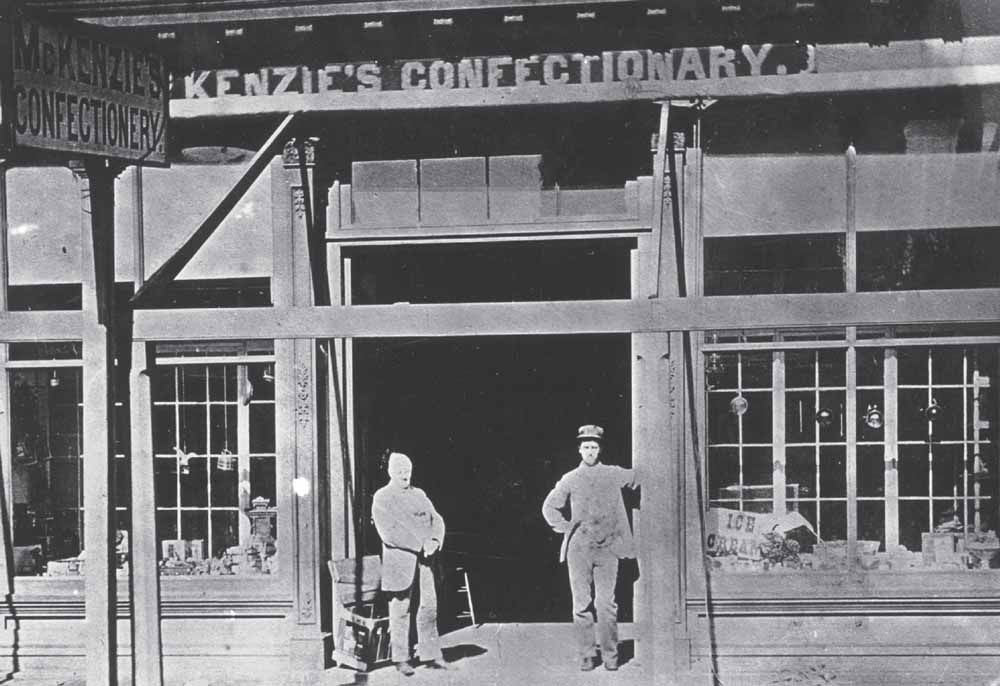

MC

KENZIE

’S

CONFECTIONERY, C

. 1880.

Independent Fire Company commander, city alderman, and confectioner John McKenzie and his wife, Adeline, rebuilt their destroyed business following its fiery demise during the Civil War. This decision proved popular with patrons who had enjoyed the wholesale and retail store’s fine candies, ice cream, toys, and “fancy articles.” The address of the couple’s Reconstruction-era building was 62 North Richardson Street, which once stood on the west side of Main Street between Plain (Hampton) and Taylor Streets. One of the store’s loyal customers was named Thomas Woodrow Wilson, a teenager who would become the 28th president of the United States. Here, bathed in midday sun, two men, the elder of whom is likely owner John McKenzie, pose for an unidentified photographer. (South Carolina State Museum.)

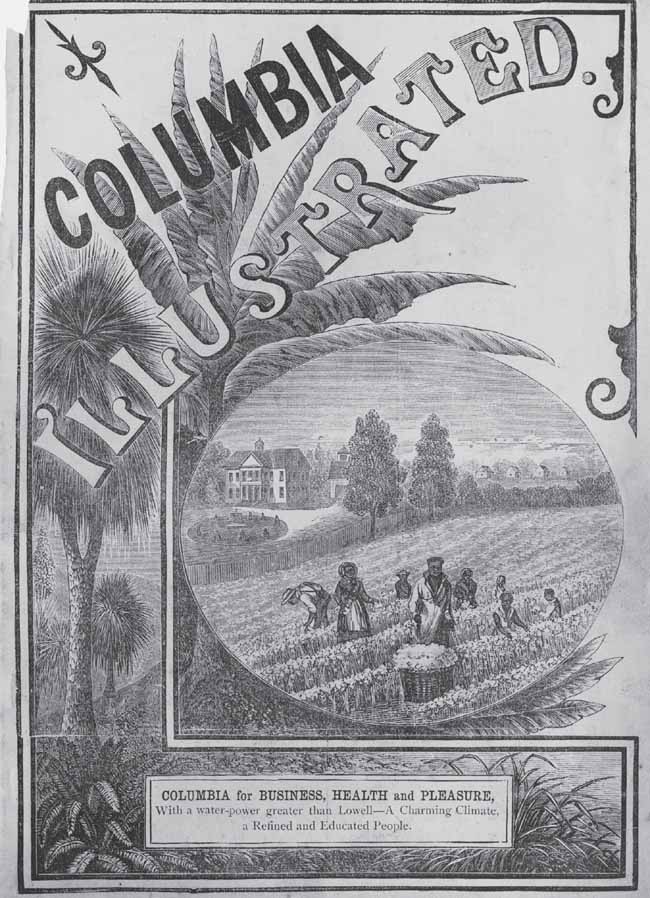

SELLING

SOUTH

CAROLINA

’S

CAPITAL

CITY

, 1881.

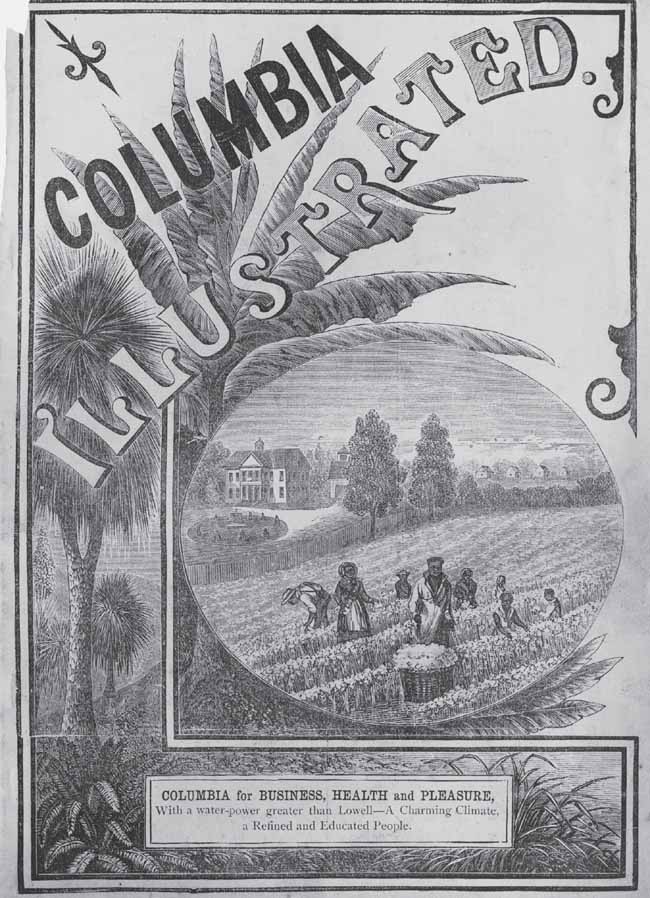

Boosters intent on luring potential investors to the capital city after the Reconstruction era shaped public perception in a variety of ways, particularly through publications. One, Columbia Illustrated Magazine

, flooded readers with statistics and background information about the state and city in addition to opportunities that awaited people interested in “Business, Health and Pleasure.” Most striking, however, was the disparity presented by the cover’s boxed-out text, which touted the city’s water power, “charming” climate, and “refined and educated people” and its lavish graphics, which spotlighted black men, women, and children picking cotton in front of a plantation house. This visual reference to a return to an antebellum status quo would have a lasting effect on how the entire nation viewed not only Columbia, but the South in general for generations to come. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2008.12.1.)

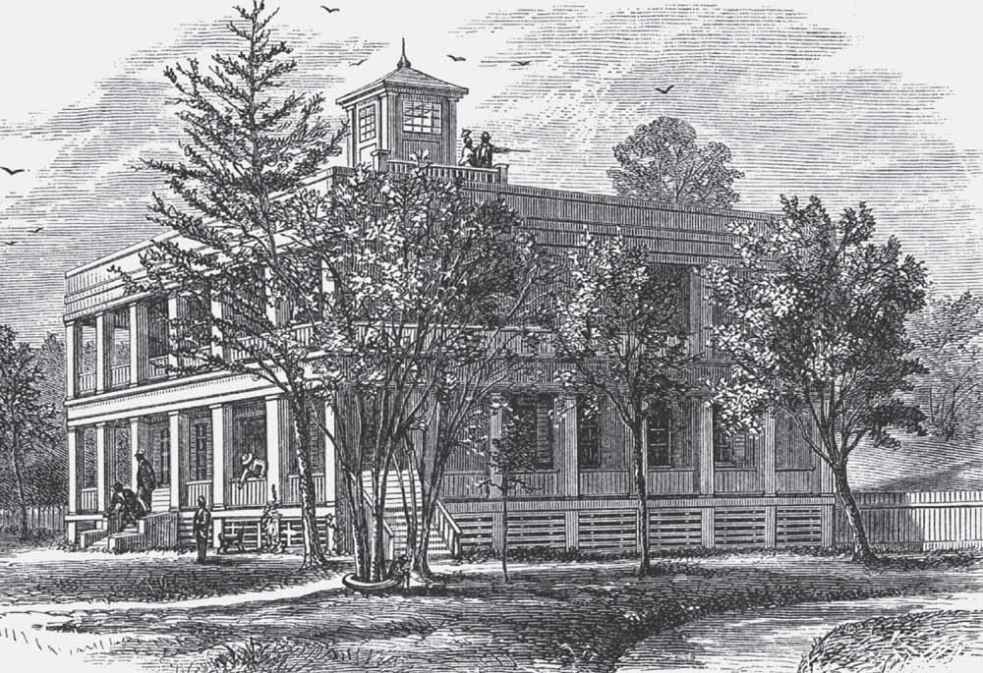

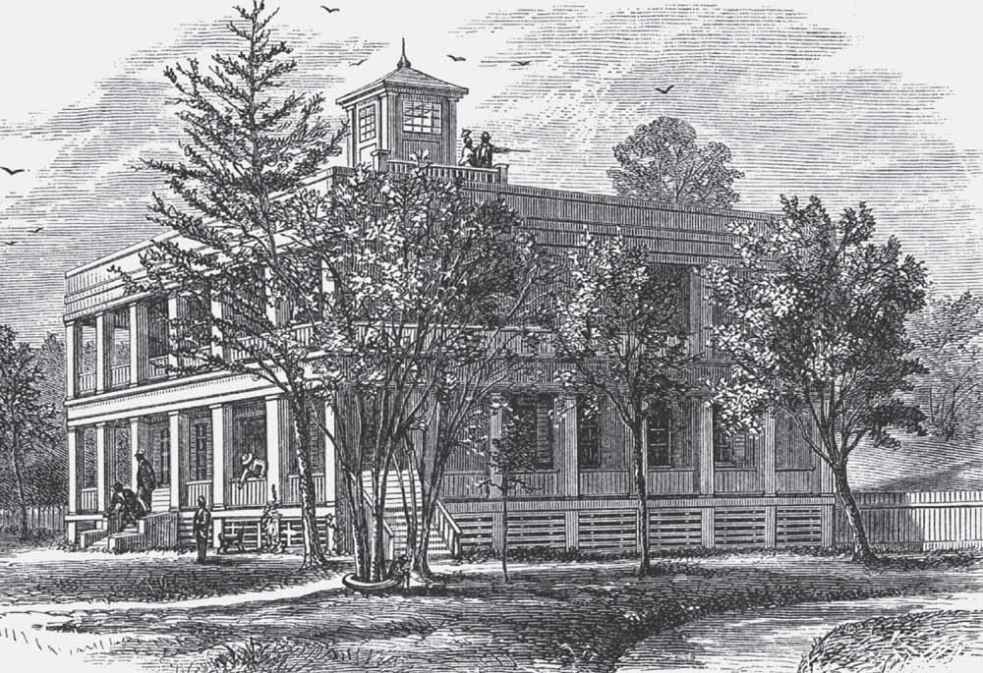

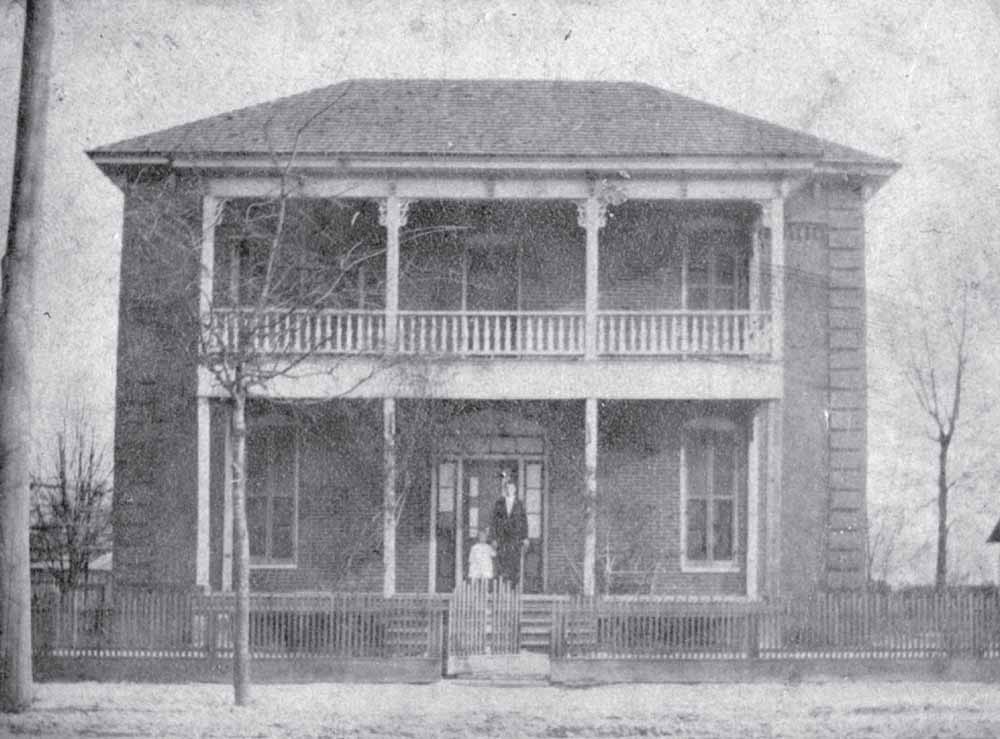

BENEDICT

INSTITUTE

, 1883.

Established shortly after the Civil War on plantation land initially owned by Robert Latta, Waverly is recognized as one of Columbia’s first suburbs and home to two historically black colleges—Allen and Benedict. Founded in 1870 by the American Baptist Home Mission Society to educate freedmen and their descendants, Benedict College was named after Stephen and Bathsheba Benedict, abolitionists from Rhode Island who helped fund the school. Initially offering primary, secondary, and college-level courses, the institution later focused solely on college students, offering blacks access to higher education during segregation. Benedict pressed Latta’s former residence into service during the school’s earliest years. Featuring wraparound porches and a cupola, the two-story mansion stood to the east of the intersection of Blanding and Harden Streets. (Historic Columbia archives.)

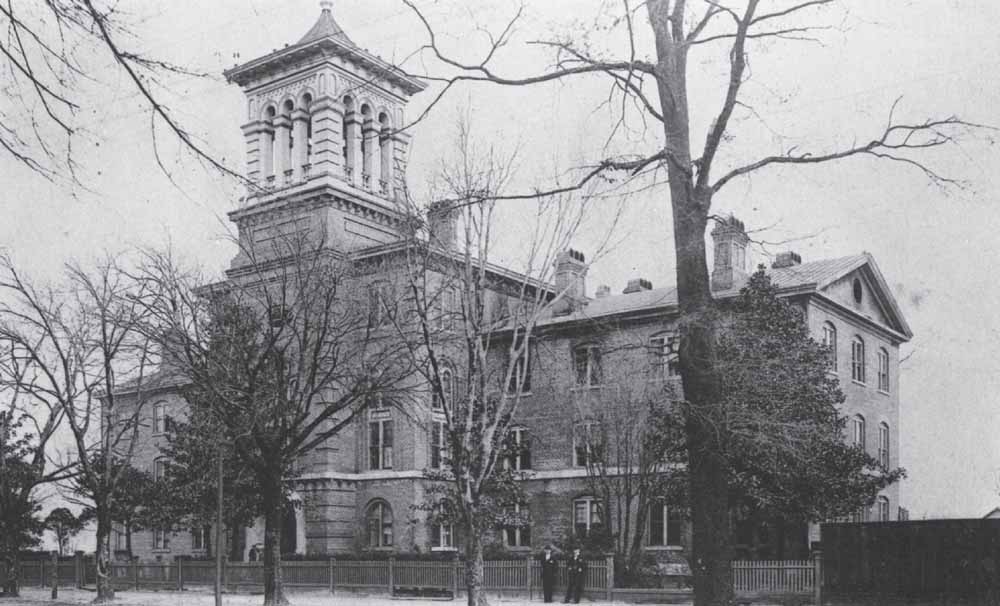

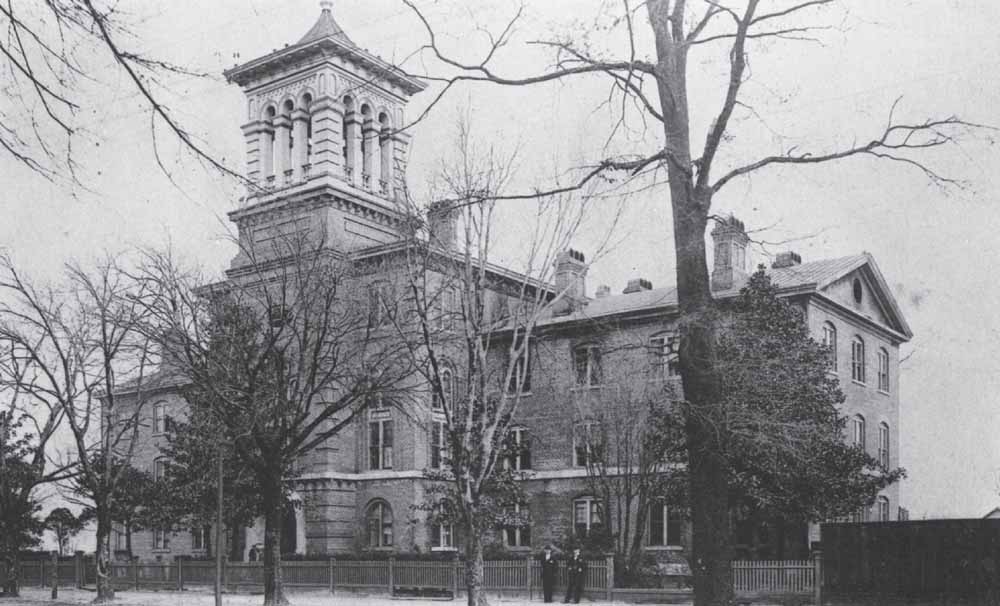

COLUMBIA

FEMALE

COLLEGE, C

. 1890.

The capital city’s skyline received a massive addition in 1858 with the completion of Columbia Female College, the precursor to today’s Columbia College. Situated on the south side of Plain (Hampton) Street’s 1600 block, the Methodist church–based school featured an iconic tower whose detailing rivaled that of most public buildings and churches. With the college closed temporarily following the Civil War, the site operated during Reconstruction as the Nickerson Hotel, a use well suited to the structure’s layout. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2008.4.1C.)

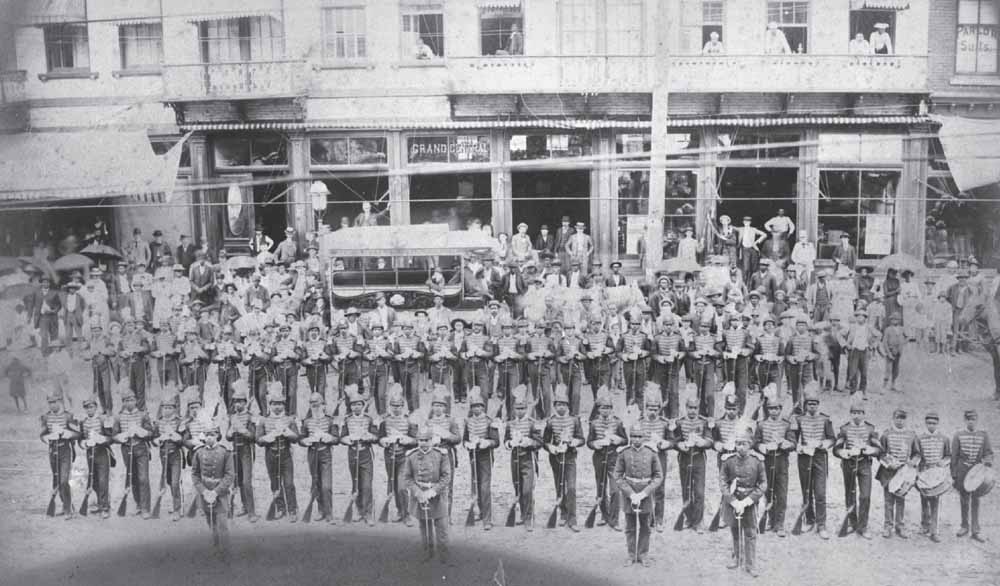

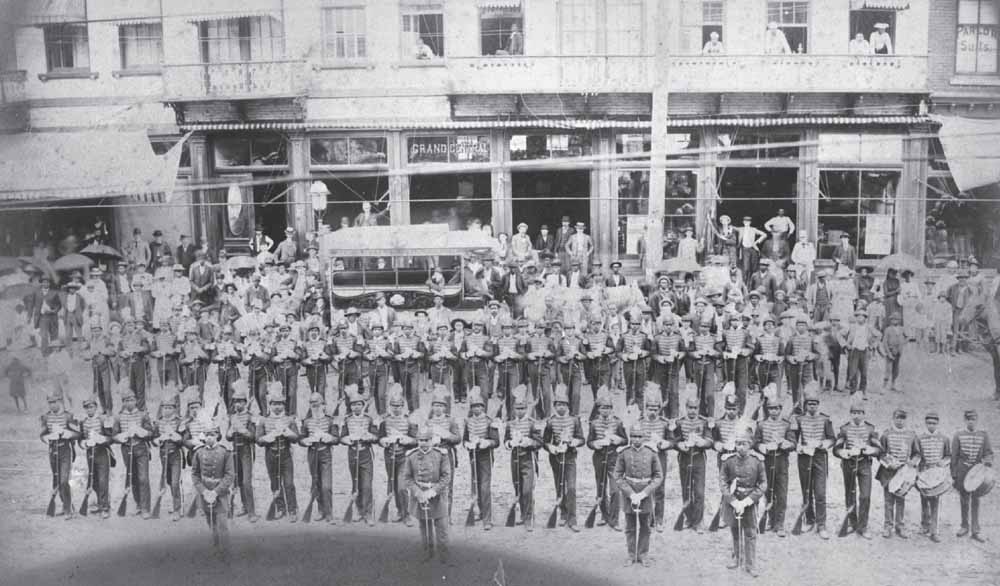

CAPITAL

CITY

GUARDS, C

. 1891.

Members of the Capital City Guards pause during one of the many parades in which they participated during the 1890s. With the Grand Central Hotel at 1444 Main Street and an elaborately decorated “bus” from Jones P. McCartha’s livery company as a backdrop, proud black men, women, and children and a handful of white men pose with what The State

newspaper called the state’s “crack colored military corps.” A Labor Day incident in 1900 involving members of the unit and white civilians led Governor McSweeney to disband the African American militia unit, known for holding orderly shooting contests, military banquets, memorial services, and benefit parties. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2011.4.1.)

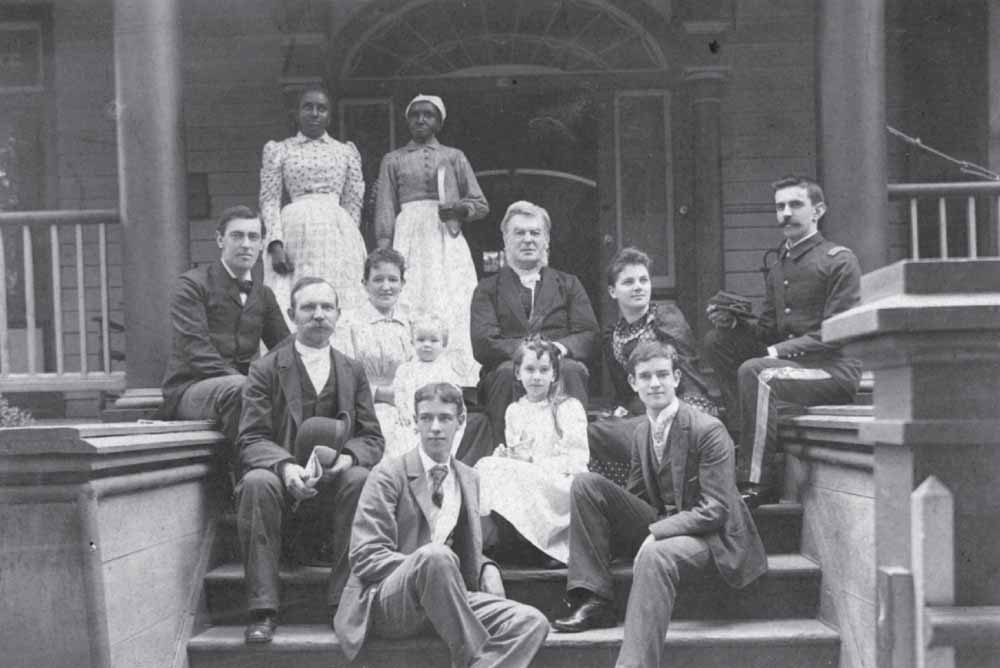

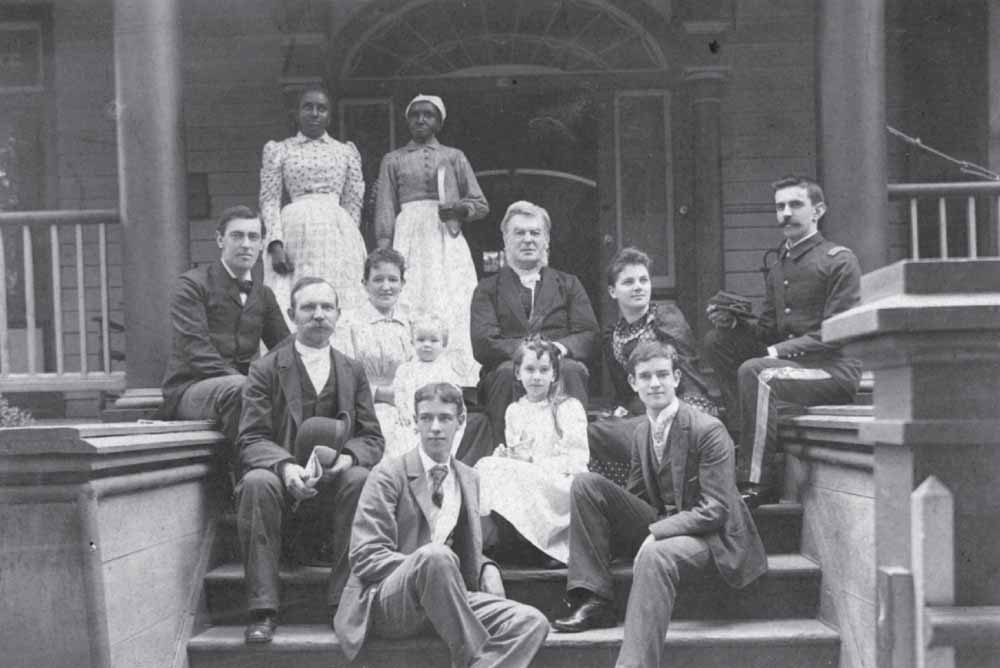

A FAMILY

GATHERING, C

. 1892.

Two decades before this photograph was taken, a teenage boy named Tommy lived two blocks away. A little more than 20 years after this family gathering, that same person lived states away, in a far larger house with far greater responsibilities. Thomas Woodrow Wilson (third row, far left) would become the United States’ 28th president, the first Southerner to hold that office since the Civil War. While his father, Dr. Joseph Wilson (third row, center), and his mother, Josephine (not pictured, deceased), left Columbia in 1874, one of his older sisters, Annie (third row, second from left), stayed in the capital city with her husband, George Howe Jr. (second row, far left). Woodrow Wilson retained ties to the capital city, occasionally visiting these and other relatives, including his uncle Dr. James Woodrow, a prominent theologian, and other members of the Woodrow family. (Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library.)

COLUMBIA

HOTEL, C

. 1895.

English architect and builder Thomas Roots Davis was among the businessmen who rebuilt Columbia following the Civil War. By 1868, he had spent $80,000 in erecting the Columbia Hotel, one of Richardson (Main) Street’s largest structures, whose prime location between Taylor and Plain (Hampton) Streets ensured its success for generations. Though updated in 1897, the inn was, by some people’s standards 15 years later, “time worn and weather beaten.” Ultimately, fires in April and September 1913 led its owner, the Lorick and Lowrance Company, to abandon the hotel business and replace it with two new structures designed solely for its hardware and grocery interests. (South Carolina State Museum.)

1500 BLOCK OF

MAIN

STREET

, EAST

SIDE, C

. 1895.

Upper Richardson (Main) Street’s complete destruction during the final months of the Civil War presented property owners with a clean slate on which to erect new buildings. Most built from 1865 through the late 1870s reflected prewar construction techniques, though almost all were masonry, to help retard fires. Many buildings incorporated cast-iron architectural elements such as balconies, decorative pilasters, cornices, circular vents, and window treatments. Durable and attractive, the majority of these Reconstruction-era structures remained largely unchanged until the early 20th century, as this image of Main Street from about 1895 attests. (South Carolina State Museum.)

RICHARD

& MIXSON

’S

BICYCLE

PARLOR, C

. 1896.

Reported by The State

newspaper to be one of the capital city’s “most enterprising and hustling” firms, the partnership of John E. Richard and William T. Mixson plied Columbians with locally made bicycles during the late 19th century. Among the models offered was the “Palmetto,” which the gas fitters and plumbers-turned-cyclists sold for $85. Operating from 1342A Main Street, the business featured stylish decor and the latest conveniences, including electricity and gas lighting. The couple pictured here is believed to be John E. Richard and his wife, Emilie. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2014.14.1.)

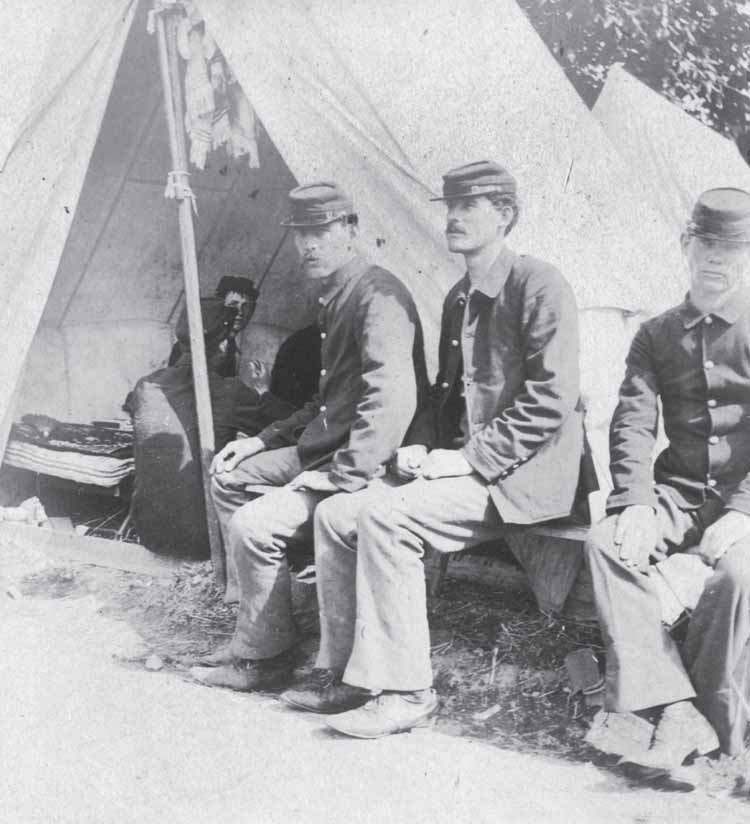

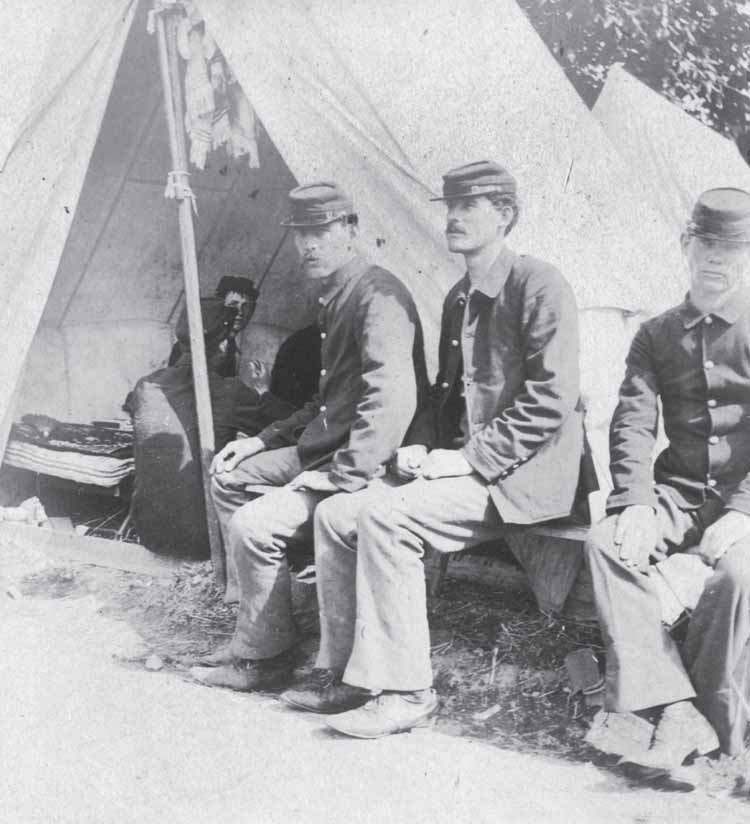

CAMP

ELLERBE

, 1898.

Based on their headgear and two-tone uniforms, these men could be mistaken for Union soldiers. However, as Spanish-American War volunteers, they were a generation removed from their Civil War counterparts. In May 1898, Greater Columbia briefly hosted four training camps, including Camp Ellerbe, established three miles north of downtown in the Hyatt Park suburb. Few men saw combat, and many were released from service four months later. Despite the brevity of their stay, a far larger contingent of soldiers, comprised of 2,500 troops from Rhode Island and Tennessee, were stationed in Columbia from November 1898 until February 1899 at Camp Fornance, located in today’s Earlewood suburb, one mile north of the original city limits. (Ensor Collection, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

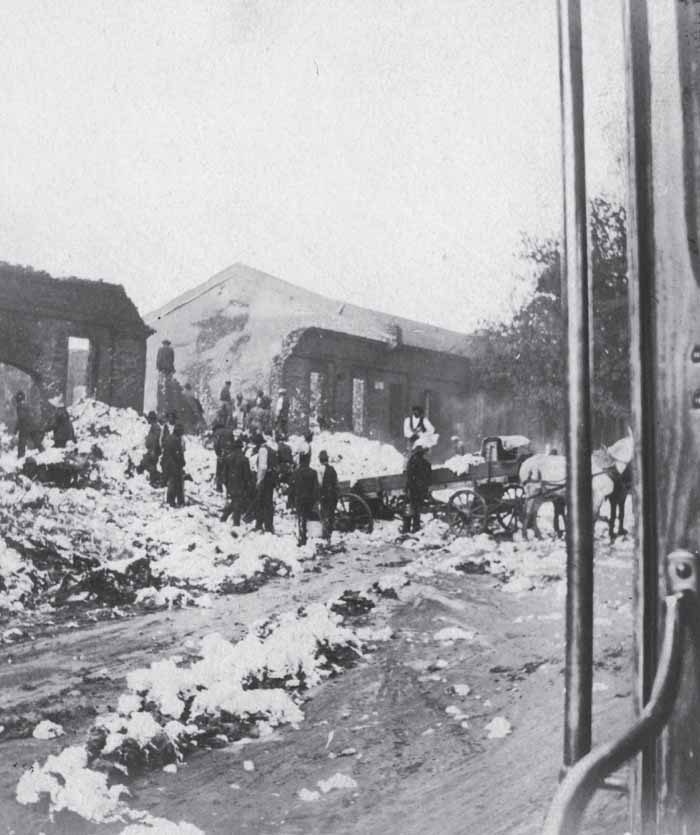

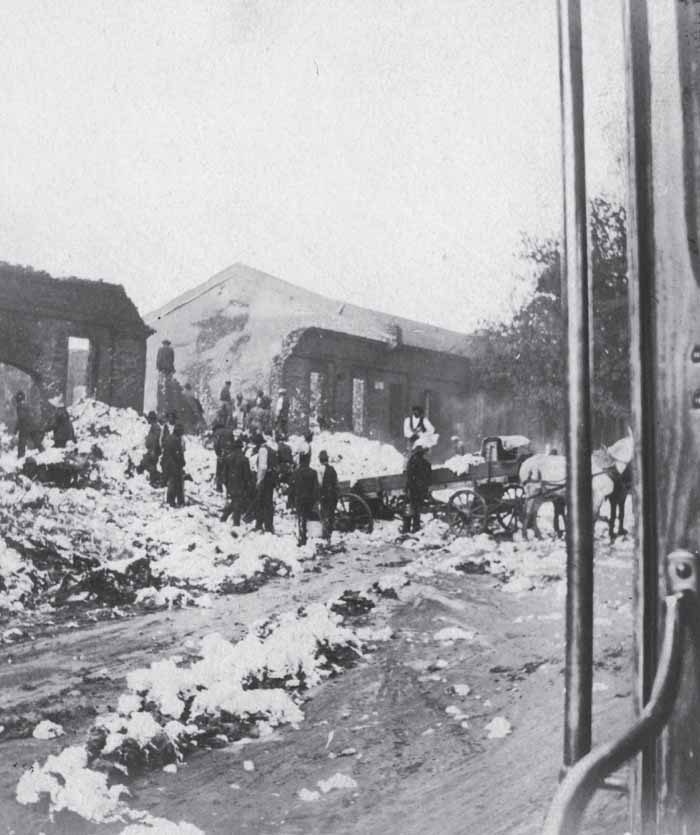

STANDARD

COTTON

WAREHOUSE

, APRIL

12, 1898.

Working amid piles that look like sullied snow, African American laborers separate singed from salvageable cotton outside section B of the Standard Warehouse at 501 Gervais Street. Shortly afterward, the facility was repaired and put to use by the South Carolina State Dispensary System, which managed the production and sale of alcohol from 1898 until 1907. Fire was no stranger to the landmark standing on the corner of Gervais and Huger Streets. More than 30 years earlier, in February 1865, Union soldiers had torched the former Evans and Cogswell Printing Plant during their occupation of Columbia. (Ensor Collection, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

AN

AFTERNOON

RIDE

, AUGUST

1898.

Dressed in a high-neck blouse, long skirt, and bolero hat, this unidentified woman exudes an air of confidence while pausing during an afternoon ride in what is believed to be the Bellevue area, north of the city limits. By the late 19th century, cycling had become popular in Columbia among both men and women. Featuring tassels, white tires, a leather seat, and tool kit, this rider’s choice in bicycles complemented fashionable clothes protected by rear fender and an elaborate chain guard. (Ensor Collection, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

MAIN

STREET, C

. 1898.

Taken from the State House looking north, this photograph offers an unparalleled perspective on Columbia’s Main Street just before the 20th century. Thanks to the largest of buildings standing little more than four stories tall, the city’s visual appeal was, arguably, at its evolutionary peak during this era. Soon, far taller buildings would follow, joining other symbols of modernity found in the electric streetcar tracks and power poles. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2008.4.1.)

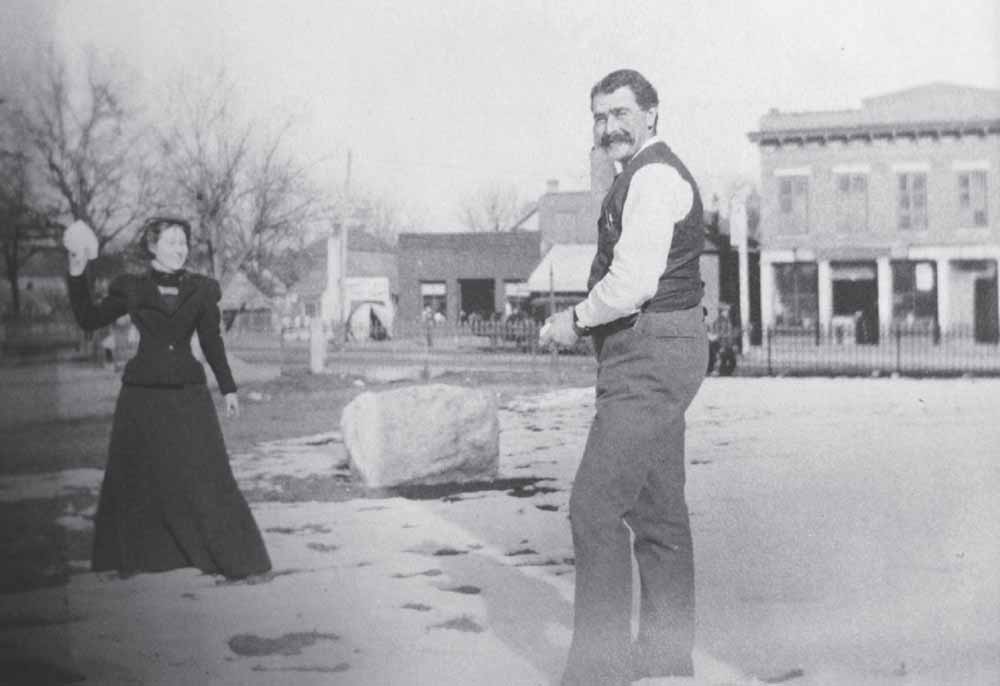

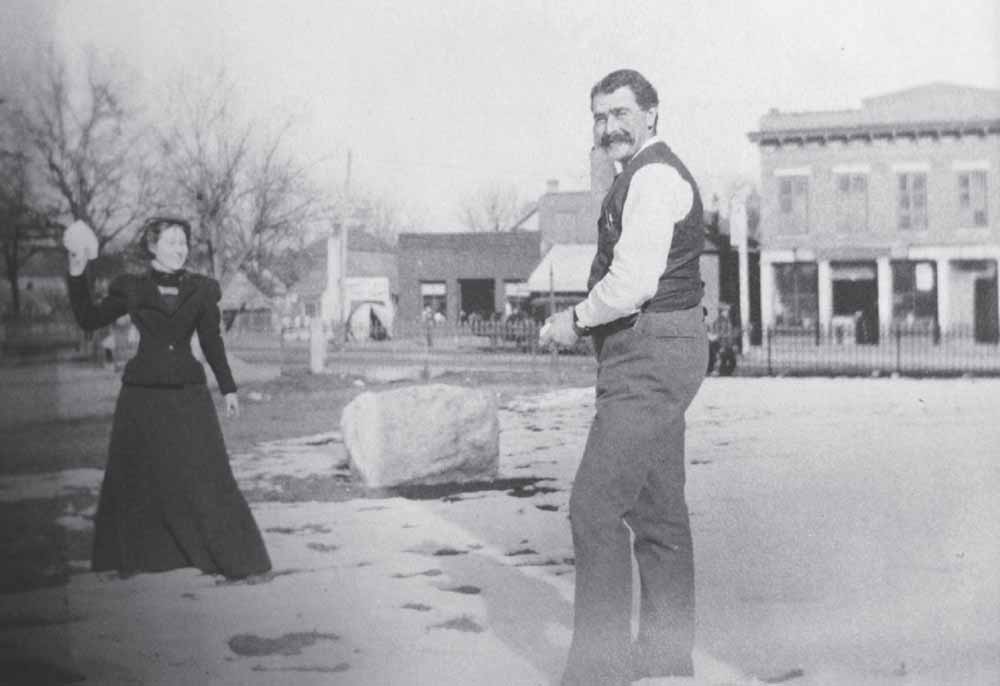

WINTER

MISCHIEF

, FEBRUARY

1899.

An unidentified couple makes the most of a thaw in the capital city, which endured zero-degree weather and about a foot of snow during the previous days. Their playground is an empty lot in the 1700 block of Main Street adjacent to what was at the time the federal post office and courthouse, which later became city hall. In the background stand Thomas Sprowl’s marble yard, on the corner of Main and Laurel Streets, and one- and two-story commercial buildings that held J.S. Dent’s meat market, R.F. Martin’s grocery store, and C.O. Brown & Company’s hardware and paint store. It is tempting to wonder whether the smartly dressed woman got the better of the well-coiffured man who appears more interested in posing for the camera than in defending himself from imminent attack. (Ensor Collection, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

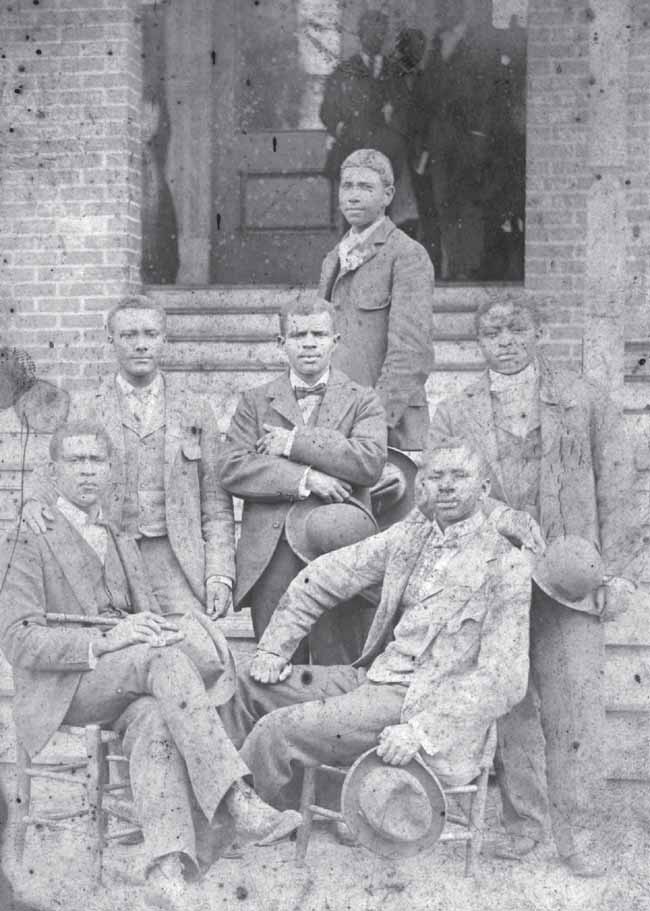

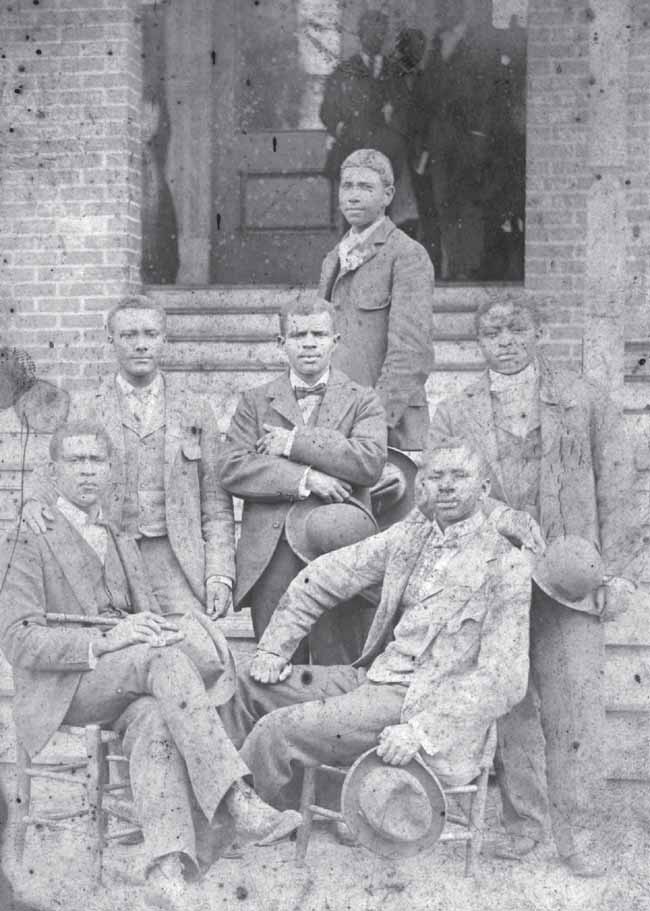

ALLEN

UNIVERSITY

STUDENTS

, MAY

11, 1899.

Neither Crosby Jackson nor the Palmetto Photo Company was listed in Columbia’s city directories for the late 1890s or 1900; however, this image, documenting six Allen University students, was printed on a card advertising both. Chartered in 1880 as an outgrowth of Payne Institute, which was founded in Cokesbury, South Carolina, in 1870, Allen initially offered primary through college-level and law school classes. From left to right are (first row) John J. Sultan and J.D. Thomas; (second row) C.L. Williams, P.Z. Arnold, and R.M. Perrin; (third row) L.F. Alston. Sultan was among Columbia’s “colored wheelmen,” who The State

newspaper reported three years earlier as having won cycling competitions held at the state fairgrounds. Williams was one of the bicycle meet’s official starters. (South Carolina State Museum.)

AN

ODD

COUPLE

, 1899.

While briefly quartered in Columbia during the Spanish-American War, soldiers often spent their off-duty hours interacting with locals. Members of the Ensor family, who assembled a scrapbook during these months, caught one of the more curious moments involving an incarcerated child and a serviceman playing prisoner. Standing in front of what appears to be temporary military housing erected in 1898, the pair is surrounded by a collection of nonmilitary creature comforts, including a spindle bedstead and bent-branch chair. The youth might have been a member of a labor gang assembled for road improvements in the suburbs that were growing north of the city at the time. (Ensor Collection, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

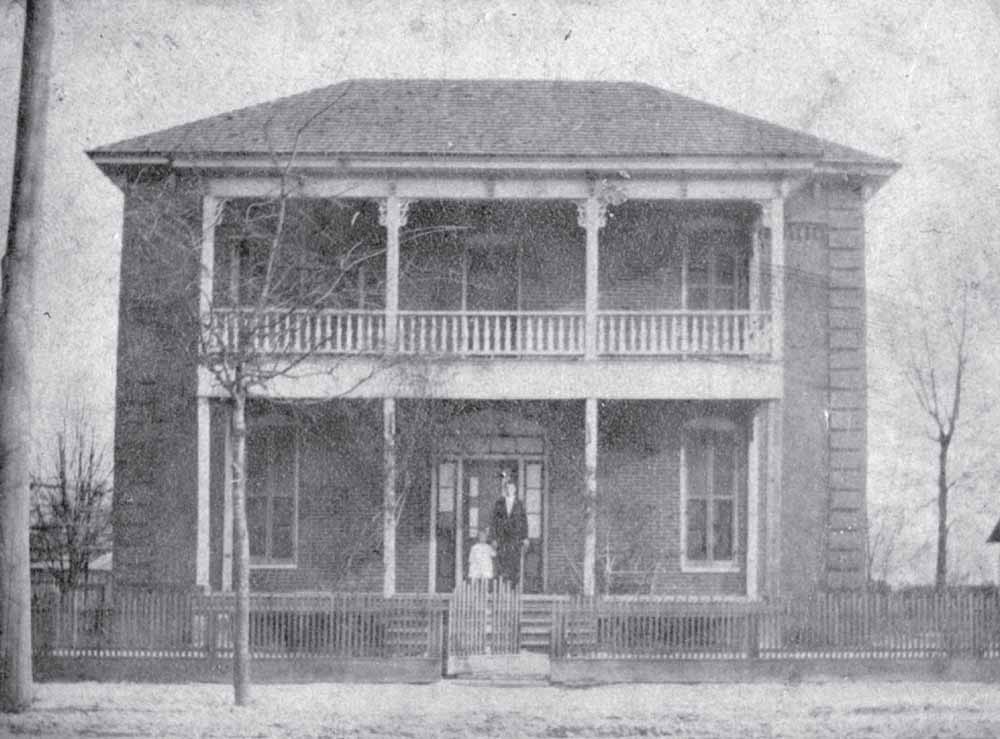

HORSFORD

RESIDENCE, C

. 1900.

Most likely built during the mid-1880s, this two-story Italianate-style residence carried the address of 622 Lumber (Calhoun) Street. Standing one block south of the original state fairgrounds that fronted Upper Street (Elmwood Avenue) and one block north of the governor’s mansion, this property was one of Arsenal Hill’s more fashionable late-19th-century dwellings. Despite its amenities, the building was demolished in 1918, following the death of its last resident, widow Mary Wood Smith, the previous year. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2014.12.1.)

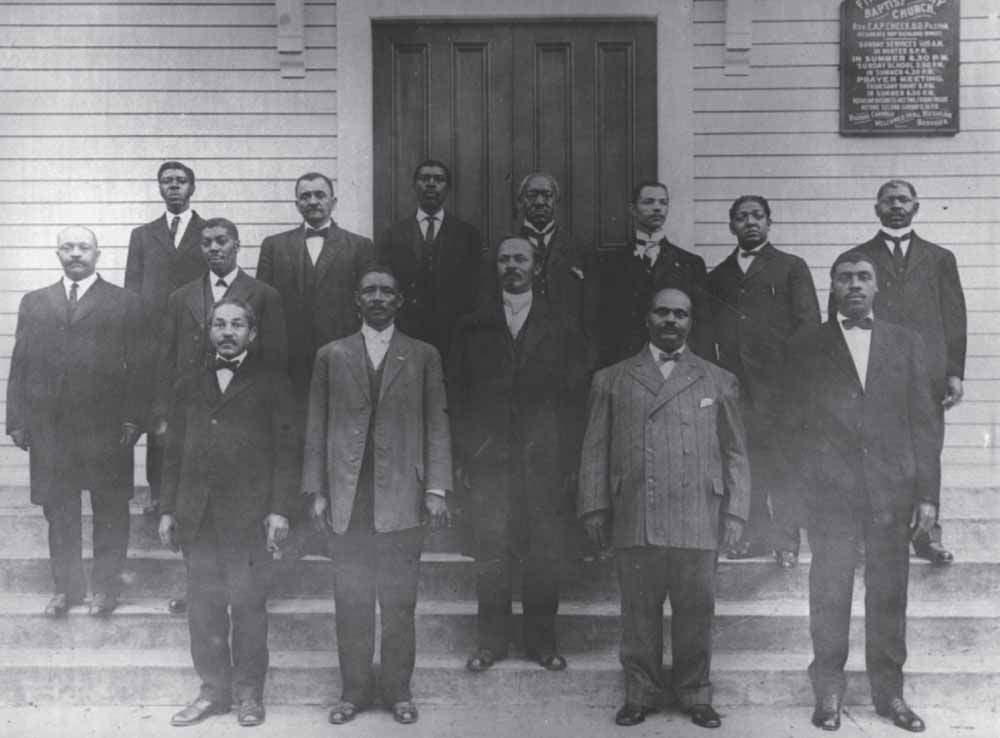

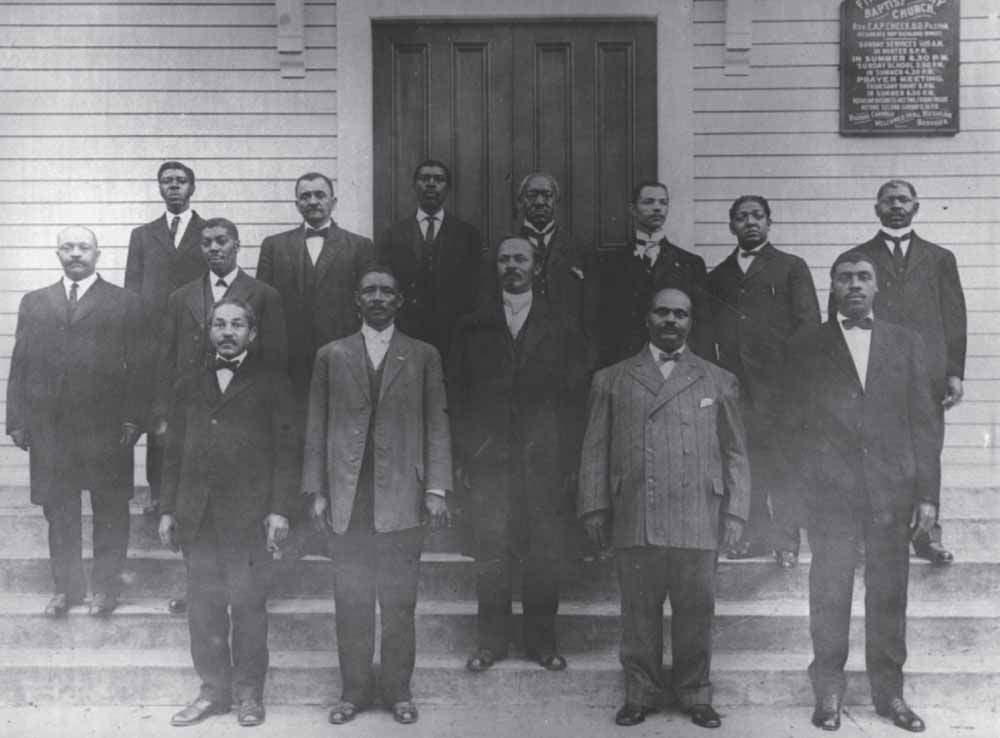

FIRST

CALVARY

BAPTIST

CHURCH, C

. 1900.

Organized under a brush arbor in 1865 as Cavalry Baptist Church, founding members of this congregation met in what today is the Mann-Simons Site before building their own sanctuary at 1412 Richland Street in 1875. Dissension among the members resulted in a split and the formation of the congregations of First Calvary, Second Calvary, and Zion Baptist. Among the elders pictured here are Charles Simons (first row, second from right) and Lucius Simons (second row, first from left). (First Calvary Baptist Church.)

SOUTH

CAROLINA

STATE

DISPENSARY, C

. 1900.

Damage from a cotton fire in April 1898 compelled the State of South Carolina to expand its existing plans to renovate J. Caldwell Robertson’s former Standard Warehouse at 501 Gervais Street, by enlarging the entire building through the addition of a second story. Following improvements, the Gervais Street landmark featured sections for bottling and storage, with six times as many compartments for liquor as for beer storage, a telling indication of citizens’ consumption habits. In 1907, after almost a decade of “spirited” debate over the merits of such a government-run system, the state abandoned its role as distiller and distributor. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

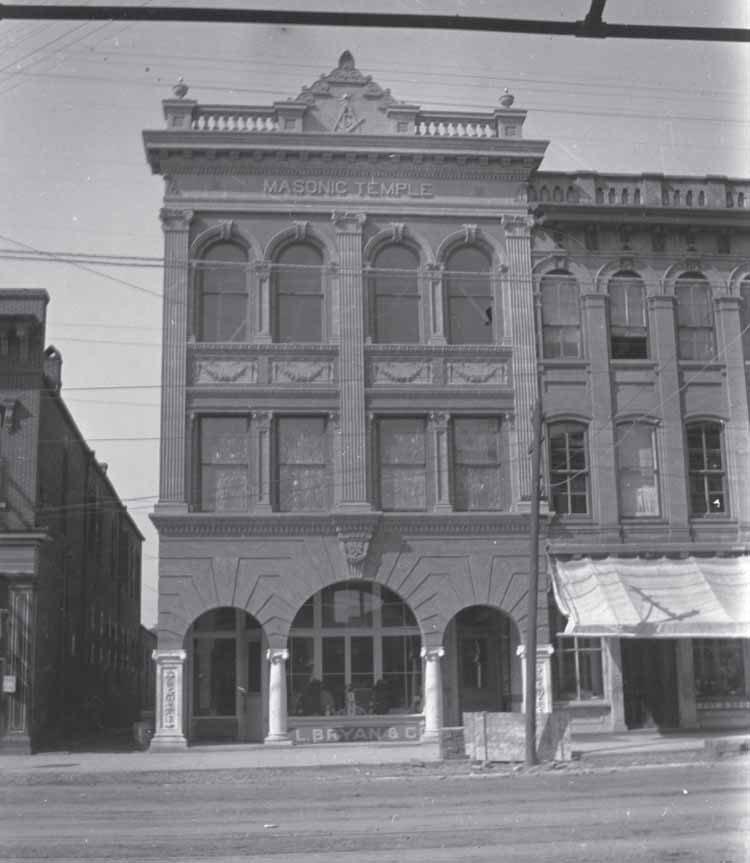

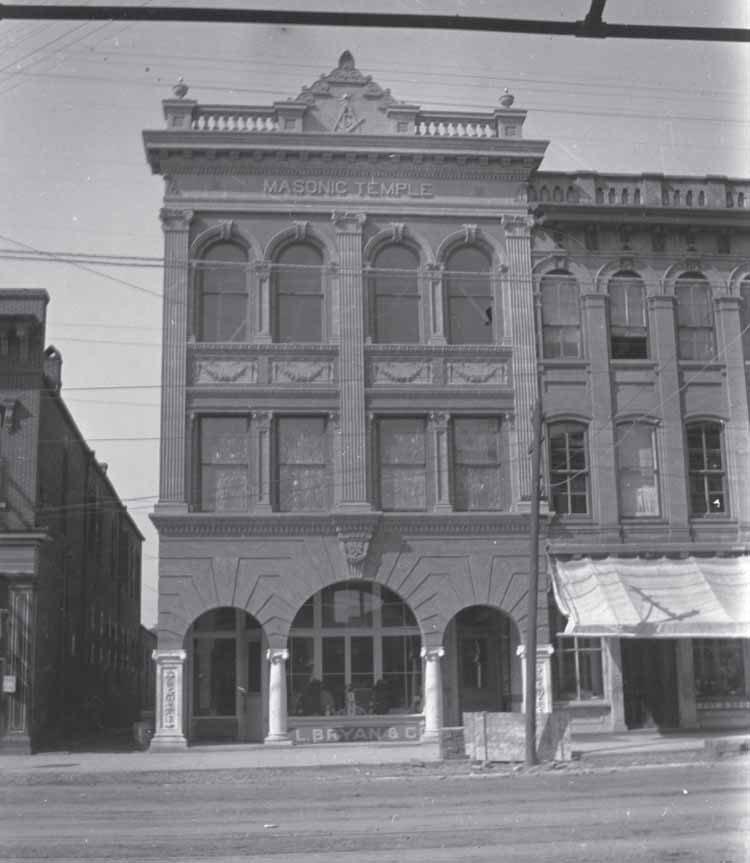

MASONIC

TEMPLE, C

. 1900.

By the late 19th century, Columbia featured a host of fraternal, social, and philanthropic organizations, some of which erected handsome buildings to accommodate their needs. Among them were the Masons, who, by the fall of 1899, built a modern three-story facility at 1425 Main Street featuring a facade of pressed brick, terra-cotta, tile, and plate glass. According to The State

newspaper, his “monument to the great order” also housed the printing and book business of R.L. Bryan Company and a dentist office. A devastating fire in March 1915 gutted the Neoclassical building, which ultimately was leveled to make way for a larger facility whose cornerstone was laid the following November. (South Carolina State Museum.)

YMCA BUILDING, C

. 1900.

From 1898 until 1911, the Young Men’s Christian Association operated from a notable landmark on the southeast corner of Main and Lady Streets. In rendering its design for the building, the Columbia firm of Lafaye and Shand embraced the tenets of Louis Sullivan, a prominent Chicago architect known for blending clean austere masses with Celtic Revival geometric and Art Nouveau floral motifs, often in terra-cotta, and incorporating large semicircular arches into his structures. Following the YMCA’s relocation in 1912 to Sumter Street, the property at 1250 Main Street remained in use by a variety of owners and tenants for over 50 years. In 1969, this architectural rarity for Columbia was demolished for the creation of a small park adjacent to a new bank. (South Carolina State Museum.)

1200 BLOCK OF

PLAIN

STREET, C

. 1900.

Two unidentified passengers wait in front of the Central National Bank on the northeast corner of Richardson (Main) and Plain (Hampton) Streets during an era in which carts and wagons were as often pulled by oxen as they were horses. Based on their clothing, the shadows, and the bank’s open windows, the photograph most likely was taken during a fall or late spring afternoon. Within five years, Swedish immigrant brothers Gustav and Johannes Sylvan would rehabilitate the French-inspired Second Empire–style building, erected in 1871, into a jewelry store by removing its corner staircase and adding a bay window for displaying merchandise. (South Carolina State Museum.)

OLD

MEETS

NEW, C

. 1900.

Shrouded in ivy evocative of an Old World dwelling, a derelict structure most likely built in the 1810s neighbors a Queen Anne–style residence from the 1880s or early 1890s. The exact location of these Columbia buildings remains debatable, as their addresses were not recorded. However, based on structural composition and the properties’ physical relationship to one another, the Sanborn Fire Insurance Company map of the city for 1898 suggests that the masonry building may be 1314 Sumter Street and the wood-frame house 1320 Sumter Street. Interesting details on the earlier building include two of its Federal-style elliptical archways enclosed and modified with windows, as well as a gambrel-like facade that does not match the gable roofline that runs the depth of the structure. (South Carolina State Museum.)

RICHLAND

COUNTY

COURTHOUSE, C

. 1900.

Columbians during the Reconstruction era witnessed the construction of several notable landmark buildings. Some were unprecedented; others were replacements for buildings lost during the fire of February 17, 1865. Among the latter structures was the Richland County Courthouse at 1237 Washington Street. Erected between 1873 and 1874, this facility, which stood at the northwest corner of Sumter and Washington Streets, remained a Columbia landmark until 1936, when it was demolished for construction of a larger facility on the same site through New Deal Public Works Administration funding. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2008.4.1D.)

A BYGONE

ERA, C

. 1900.

A trio of young ladies poses for an unidentified photographer around the close of the 19th century. The 1.5-story residence behind them is 1528 East Plain (Hampton) Street, owned in 1860 by Sarah Moore and demolished between 1915 and 1919. To the structure’s left lies Pickens Street, tree-lined and stretching to the south toward Washington Street. This area of Columbia was heavily residential for the better part of the 19th through the mid-20th centuries, until post–World War II redevelopment led to mass destruction of historic buildings. (Historic Columbia archives.)

OLYMPIA

MILL

, 1903.

Already a respected textile engineer, W.B. Smith Whaley distinguished himself further in 1900 at the debut of the world’s biggest cotton mill operating under a single roof. Olympia was powered by electricity of its own making, not from power drawn from the hydroelectric plant situated on the Columbia Canal, as was the case with Granby Mill, its smaller 1897 predecessor standing immediately east. With the addition of Whaley’s latest creation, the capital city boasted six textile mills employing nearly 3,500 workers, who left a lasting impact on the city’s footprint and culture. (Phelps Bultman.)