FIVE

“MOVING

FORWARD AND

GATHERING

MOMENTUM

”

A MODERN

CITY FOR A

NEW

CENTURY

, 1900–1930

At the dawn of the 20th century, The State

newspaper asserted that Columbia was on the cusp of a building boom that would propel the city in ways previously unimagined. Soon thereafter, real estate brokers decried a “Famine of Stores and Houses for Rent,” meanwhile imploring property owners to erect new residences and commercial buildings to keep up with demand. Others noted that all of the city’s “knockers” had died off, replaced by citizens who championed the capital city’s advantages.

The next decade witnessed tremendous municipal improvements and private ventures that created the infrastructure necessary for Columbia to grow further. The population swelled thanks to a healthy economy, the expansion of the mill communities, and the creation of Camp Jackson in 1917. Existing suburbs burgeoned. New ones, platted out where fields had stood previously, soon bustled with new bungalows, cottages, and four squares.

This progress resulted in new landmarks, new neighborhoods, and new Columbians with a heady excitement for what the future could and should hold for a city whose citizens had shaken off the fetters of a previously sleepy town. Hand-in-hand with progress, concern arose over the cost of modernity, voiced by those keenly aware of substandard working-class housing, sanitation, and municipal appearances. At the onset of the Great Depression, triggered by the stock-market crash of October 1929, Columbia, with its 51,000 residents, was far removed in so many ways from its former self just three decades earlier.

W.B. SMITH

WHALEY

RESIDENCE

, 1904.

Builder Clark Waring erected this grand Queen Anne–style building in 1893 as a residence for Charleston native William Burrows Smith Whaley. The quality and size of the property at 1527 Gervais Street reflected Whaley’s success as a mechanical engineer and designer of multiple mills throughout Columbia (he would design 21 cotton mills during his career). While in partnership with architect Gadsden E. Shand, Whaley codesigned the city’s Olympia, Granby, and Richland Mills. Whaley was also the president of the Mill Stable Company and the Columbia Electric Street Railway, the latter of which played an essential role in the capital city’s development and suburbanization. Whaley and his family remained at their fashionable home until 1903, at which point they moved to Boston. Most Columbians associate the local landmark with Dunbar Funeral Home, which operated at the property from March 1924 until 2008. (Phelps Bultman.)

MILLS

AVENUE

DEPARTMENT

STORE

, 1904.

Central to the concept of mill communities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the ability of commercial, educational, spiritual, and recreational needs being met without workers having to leave their own neighborhoods. This arrangement worked well for large companies that sought to control much of their employees’ lives. Some people living outside the mill communities found this arrangement desirable, too, as they felt buffered by the insularity of such miniature towns, which often were perceived as breeding social and health problems for the larger urban context. Central to life in the Olympia-Granby community was the company store at 701 Whaley Street, which, three years after its construction, was used as a community meeting space and recreational facility. By 1909, the venue served as a YMCA, featuring one of the area’s nicest swimming pools as well as a gymnasium, bowling alley, theater, kitchen, and reading rooms. Later, the site was called the Pacific Community Association Building. (Phelps Bultman.)

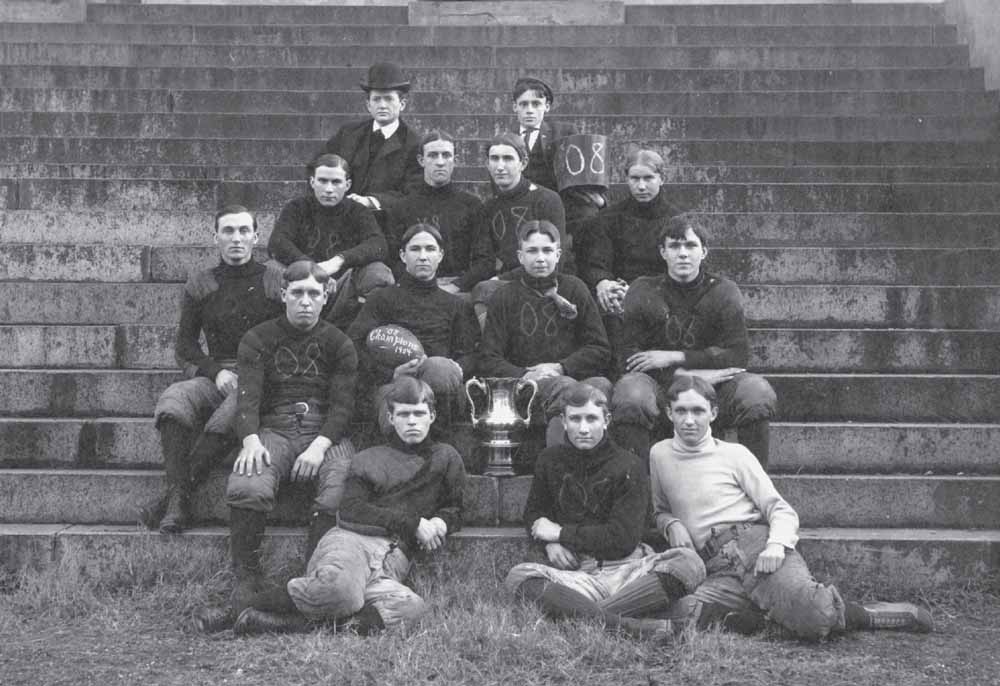

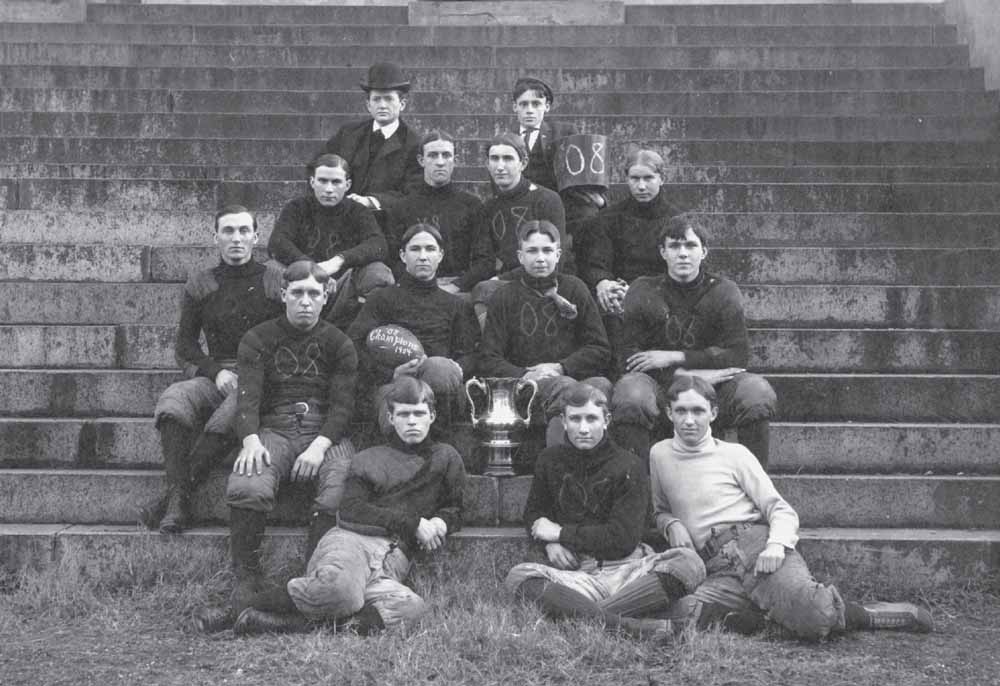

LEATHERHEADS

, 1904.

Sporting fashionable haircuts and much of the latest in safety equipment (their leather helmets are not shown), members of South Carolina College’s football team gather on the steps of Sumter Street’s Longstreet Theater during the early years of the sport’s history in Columbia. Little more than a decade separated this championship trophy–bearing squad from the first team fielded by the school in 1892. Far smaller in number and physical size than modern teams, early gridiron contestants were divided into varsity, class, and scrub teams. Schedules featured fewer intercollegiate games. Most matches resulted in rather low scores, though at times the stronger club hung considerable points on their less talented opponent. Carolina’s teams sometimes challenged athletic clubs and even high schools in addition to their college matches. (Martha Fowler.)

LAUNDRESS AND

CHILD

, FEBRUARY

4, 1904.

Following the Civil War, Columbia’s landscape changed in ways that reflected an increasingly greater division between blacks and whites. Far more integrated prior to emancipation, both races delineated space in ways that reflected aspirations of community. Working-class African Americans often lived on the periphery of more established white communities or within the center of blocks where white-owned residences faced the streets. (AMNH 48042, American Museum of Natural History Library.)

1900 BLOCK OF

MAIN

STREET

, MARCH

4, 1904.

During the winter of 1904, photographer Julian Dimock predominantly trained his lens on working-class African Americans, many of whom were either formerly enslaved or were one or two generations removed from bondage. Though focused on an elderly man plodding through downtown, Dimock also captured landmarks such as J.E. Dent’s Meat Market and Grocery Store, which stood at 1901 Main Street, and a number of residences that once lined the thoroughfare. In a role atypical of the era, the well-dressed Caucasian woman appears in the frame almost as an afterthought. (AMNH 47920, American Museum of Natural History Library.)

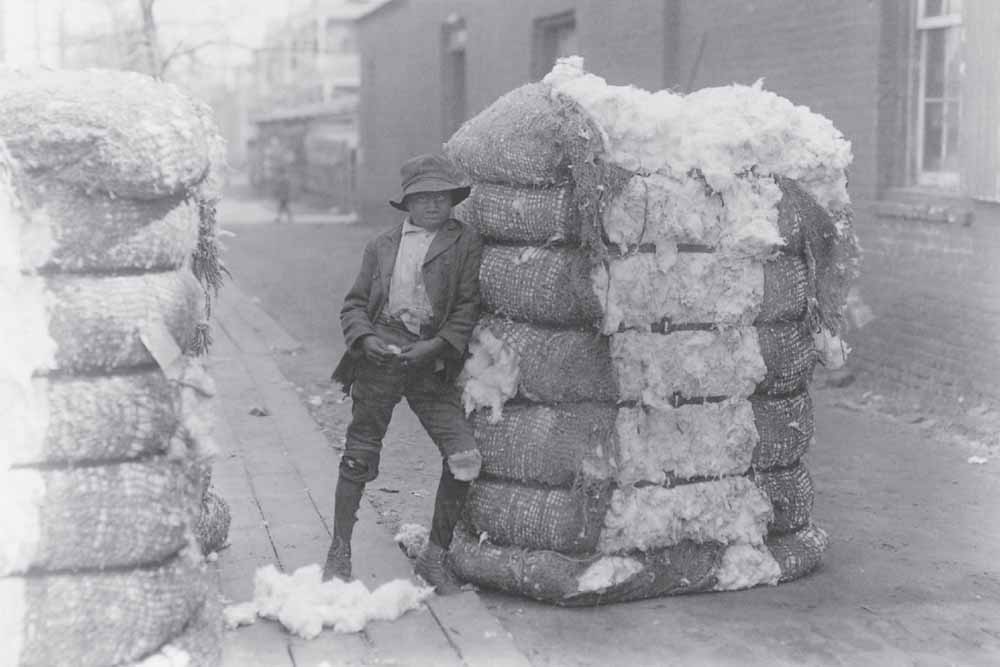

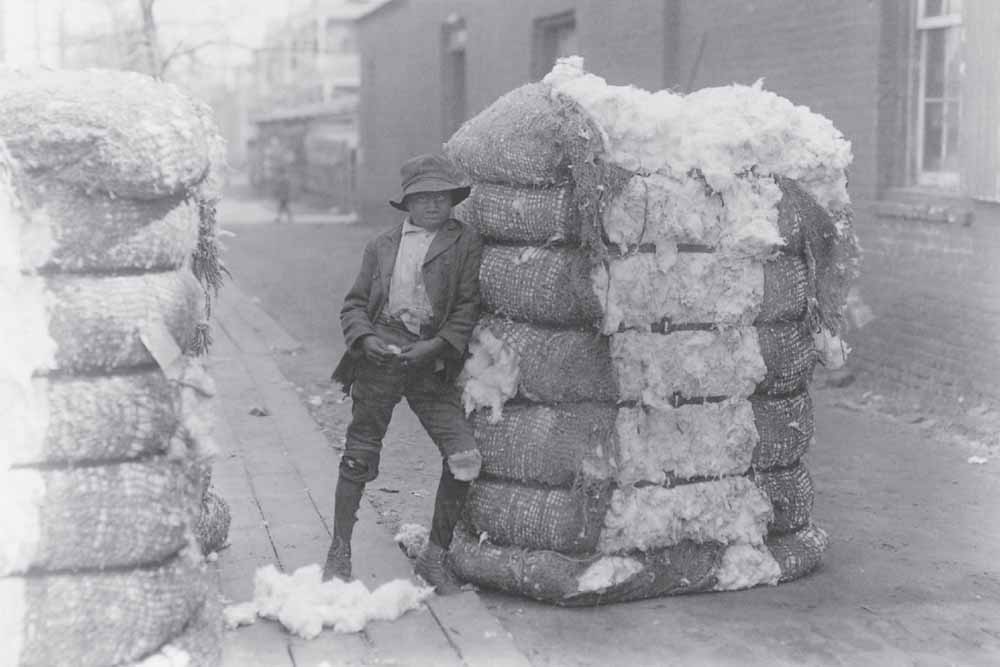

WAREHOUSE

WORKER

, COTTONTOWN

, MARCH

19, 1904.

Perhaps no older than 10, this young Columbian so firmly leans into a bulging bale that he seems inseparable from the commodity he may have helped process. Cotton, the backbone of South Carolina’s economy for generations, was processed and stored in two key locations within the city—in what is known today as the Congaree Vista, located between the Congaree River and Assembly Street, and Cottontown, a neighborhood of residences, stores, and warehouses situated near Upper Street (Elmwood Avenue). This young laborer is standing next to the fire-resistant two-story brick building of grocer E.K. McQuatters, located on the southeast corner of Main Street and Elmwood Avenue. Easily distinguishable in the background are the front porches of four residences that stretched east toward Sumter Street. (AMNH 47793, American Museum of Natural History Library.)

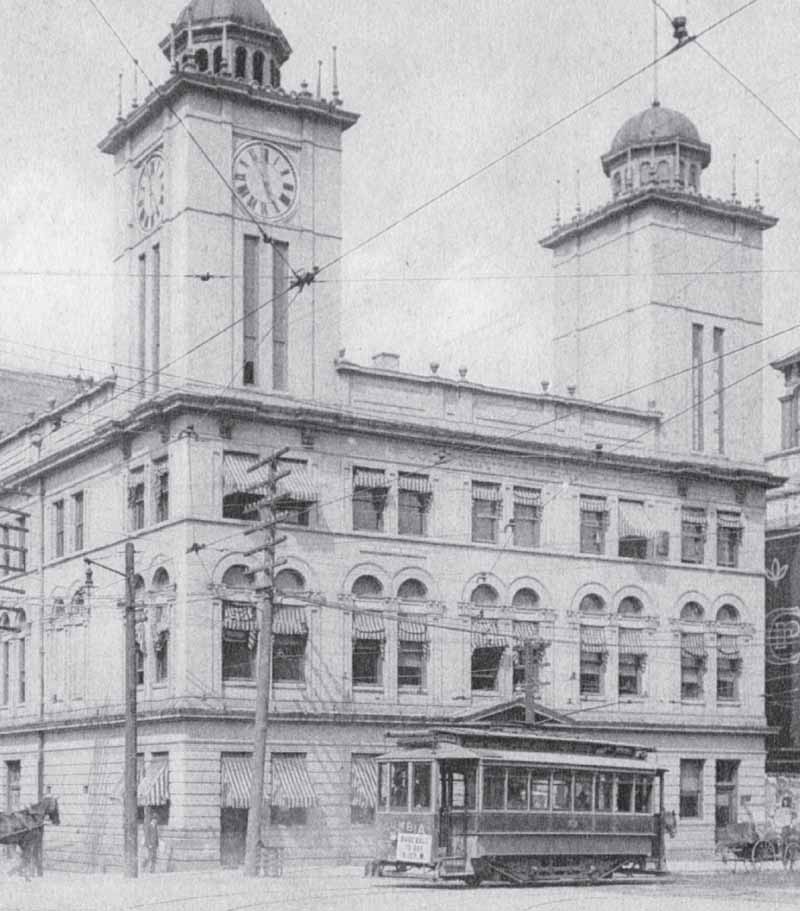

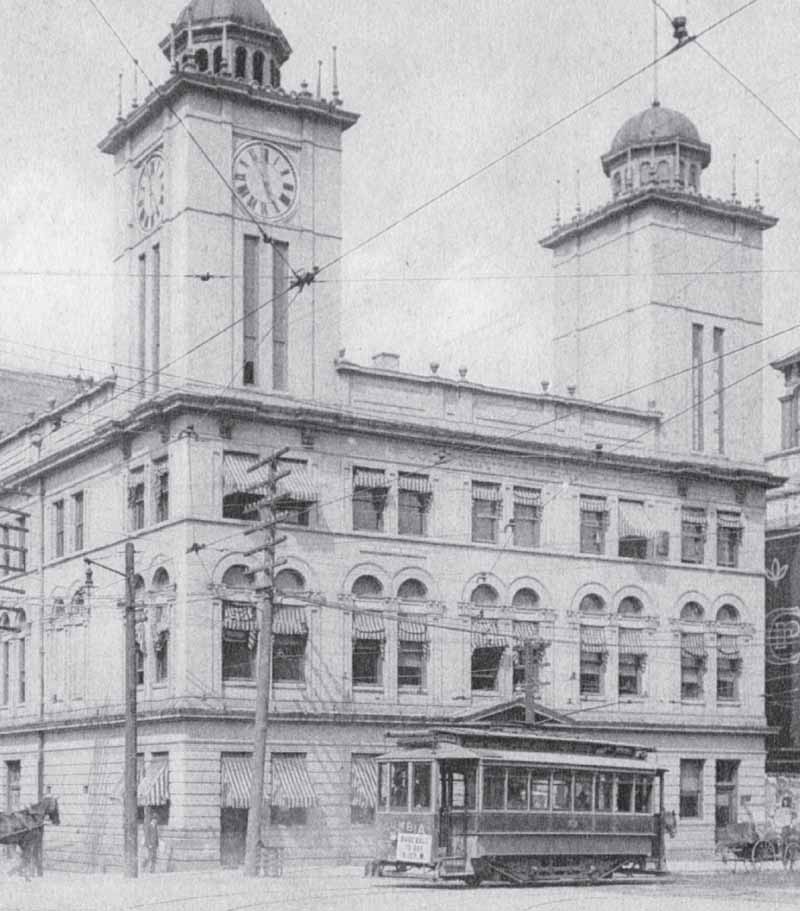

CITY

HALL AND

OPERA

HOUSE, C

. 1905.

One of Columbia’s grandest landmarks opened on December 1, 1900. Hailed by The State

as a “Thespian temple,” the Second Renaissance Revival–style structure at 1201 Main Street replaced an impressive, though less advanced, predecessor from about 1874 that burned in 1899. While mimicking Broadway’s Wallack’s Theatre in arriving at his design, Charlotte architect Frank P. Milburn bested Columbia’s northern inspiration in certain amenities, including fire-safety measures, capacity, and arrangement of seating. At three stories and sporting twin towers, one holding an oversized clock and the other a bell, the joint entertainment venue/government building made for an impressive gateway onto Main Street. After years of notable live performances, the opera house closed in 1932, having yielded to the realities of the Depression era. Retrofitted with a silver screen and rebranded as the Carolina Theater, the site offered less costly and increasingly popular moving pictures in place of the expensive live entertainment for which it was once renowned. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2007.6.81.)

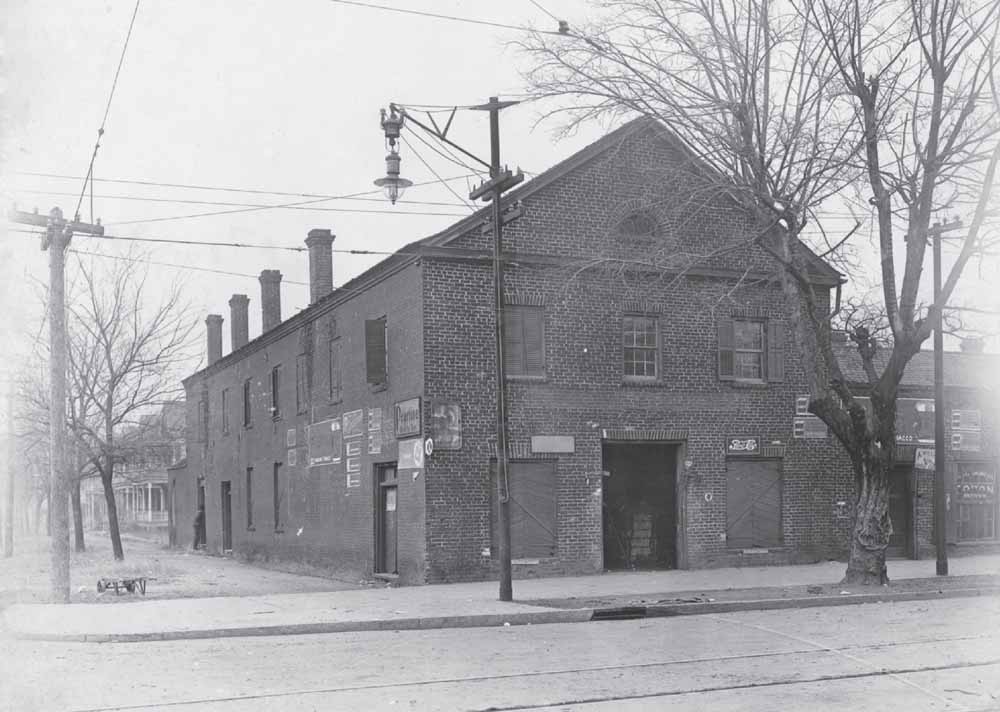

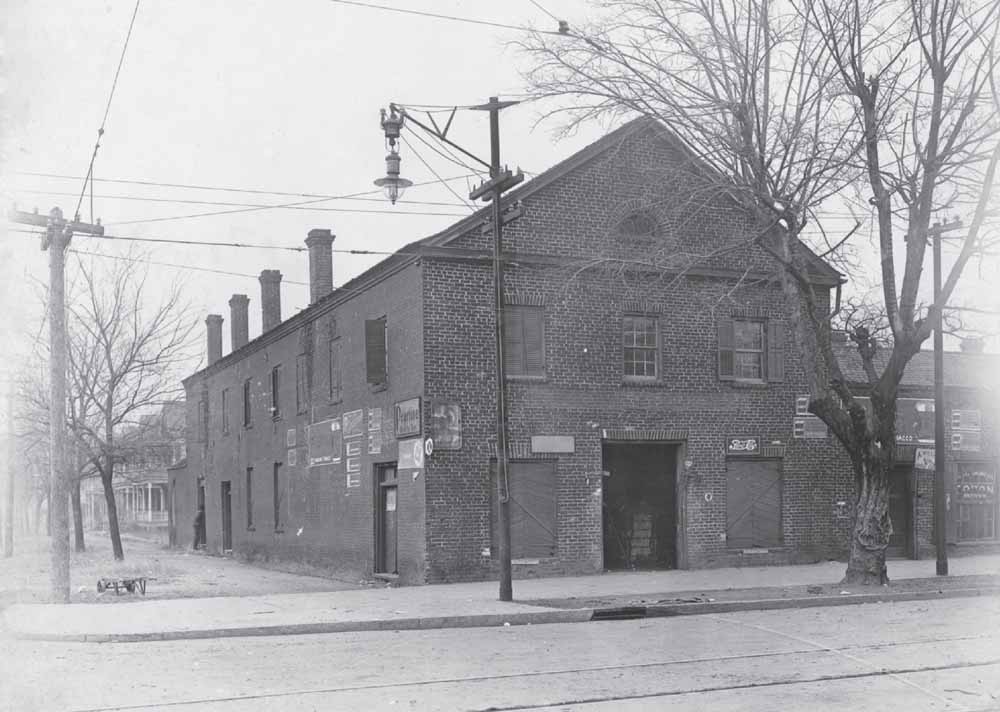

COTTONTOWN, C

. 1910.

A photograph taken about six years after Julian Dimock’s work offers greater details of the Cottontown neighborhood. Easily distinguishable is the one-story facility adjoining the Main Street store on its south elevation, operated by cotton buyer Edward Talley Tarrer. Though the exact dates of construction remain unclear, both buildings at 2028–2030 Main Street were standing on the property by 1872, when cartographer Camille Drie rendered his bird’s-eye-view map of the city during Reconstruction. Interestingly, the presence of a bale in the open doorway suggests that the McQuatters’ grocery business may have grown by this time to include some provision for storing cotton. (South Carolina State Museum.)

THE

COLONIA

HOTEL, C

. 1910.

A comprehensive renovation transformed the former Columbia Female College at 1614 Hampton Street into a fashionable Spanish Colonial–style resort hotel. Opened in January 1907, the Colonia was, according to The State

newspaper, “situated in the best residence section of South Carolina’s beautiful capital city” and promised premium treatment for guests with a discriminating taste for leisure. The posh destination featured the latest creature comforts, including an electric elevator, steam heat, long-distance telephone service in every one of its 116 guest rooms, a 200-person dining room, and first-class service and equipment. The hotel closed in 1914. After use by Columbia Bible College from 1925 until 1958, the building, by then dilapidated, was demolished in 1963. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 2007.6.49.)

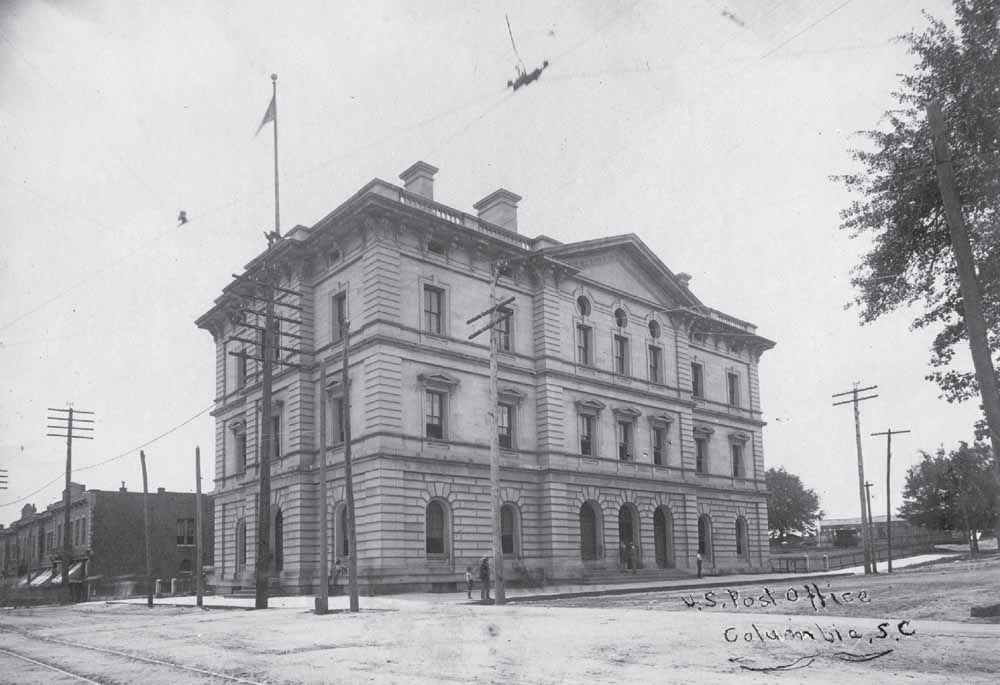

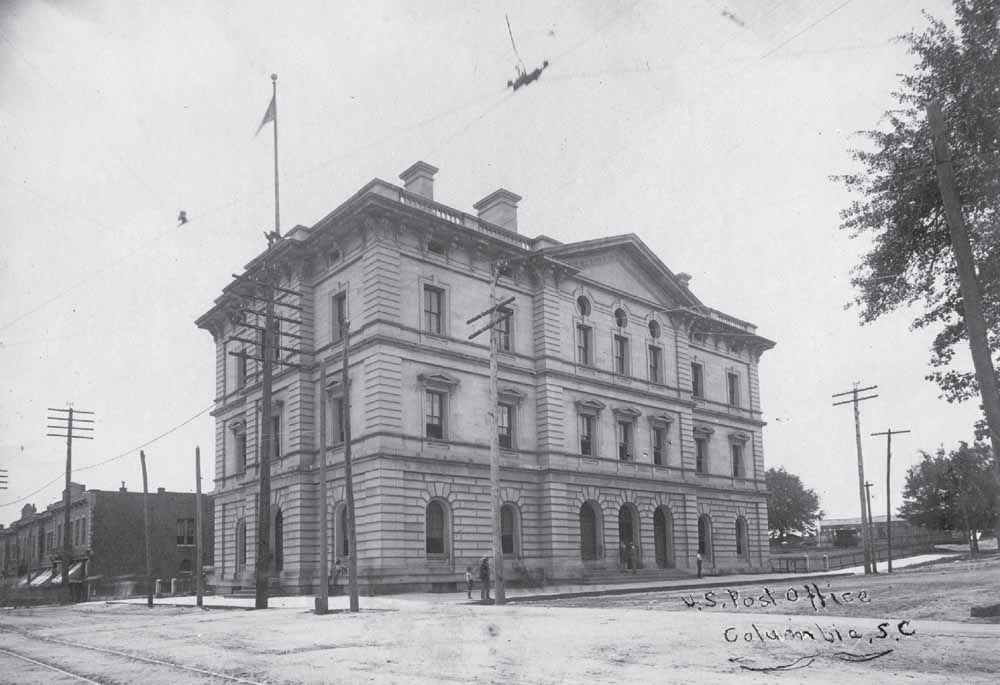

US POST

OFFICE, C

. 1910.

Alfred B. Mullet, the United States’ supervising architect during much of the Reconstruction period, designed a US Post Office and federal courthouse for Columbia in 1870. Built between 1874 and 1876, the $400,000 Italian Renaissance Revival–style facility at 1737 Laurel Street represented the federal government’s authority in and commitment to the capital city following the Civil War. This photograph offers a unique perspective on buildings that stood on Main and Laurel Streets in the first decade of the 20th century. Roughly 20 years later, in 1932, the City of Columbia acquired the property for use as city hall when it gave the federal government the parcel to the west (seen at right, on which, in this image, stands a blacksmithing and woodworking shop) for construction of a new courthouse. (South Carolina State Museum.)

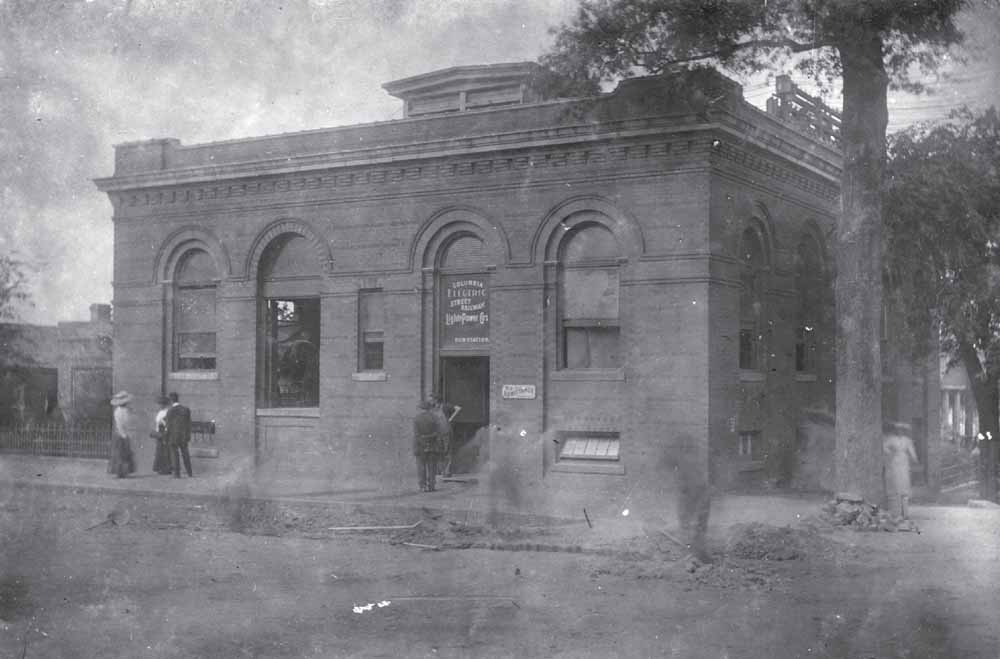

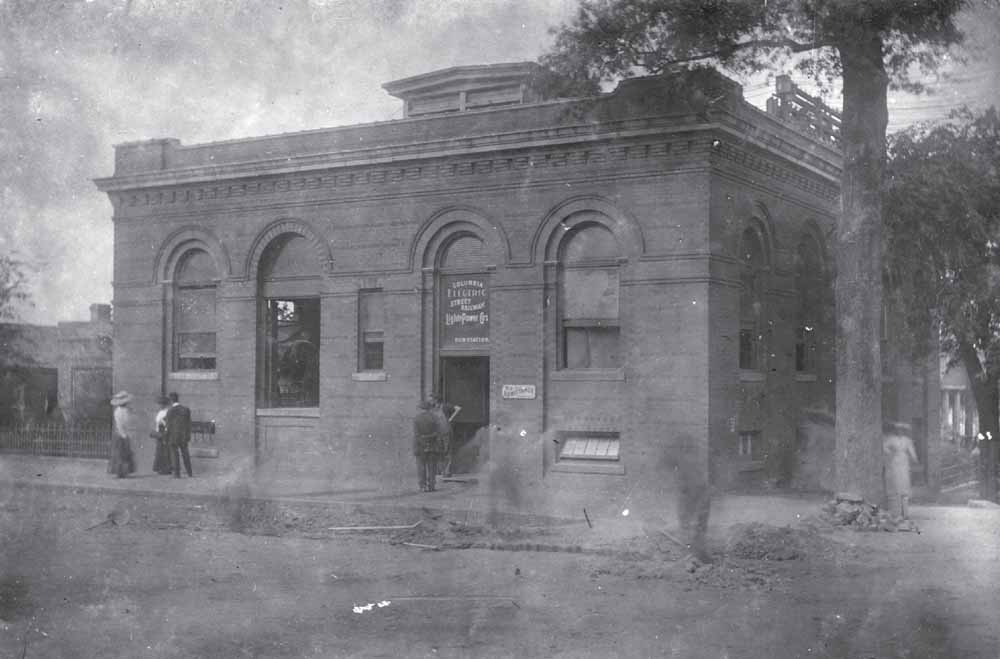

COLUMBIA

ELECTRIC

STREET

RAILWAY

, LIGHT

& POWER

COMPANY

BUILDING

, 1911.

Built about 1901 for the corporation that provided power for Columbia’s businesses, homes, and streetcar service, this architecturally distinct structure at 1337 Assembly Street originally held offices and a substation that switched electricity generated by the Columbia Canal and Olympia Cotton Mill from alternating to direct current. Major improvements to and expansion of streetcar lines led to the enlargement in 1911 of the Romanesque Revival–style facility for heightened electrical output. At the same time, the company changed its name to the Columbia Railway, Gas & Electric Company. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

MUNICIPAL

IMPROVEMENTS

, MAY

1911.

Sporting a smart bow tie and bib overalls, an unidentified drayman engages the brake of his Model 1909 Packard three-ton truck as African American laborers fill its bed with pipe recently unloaded from the nearby railroad flatcar. Priced at roughly $2,800, the Packard truck was an advanced vehicle boasting a top speed of 12 miles per hour with a body style that could be customized according to its owner’s needs. This image chronicles improvements to the city’s gas, electrical, and streetcar service lines that were made between 1911 and 1912. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

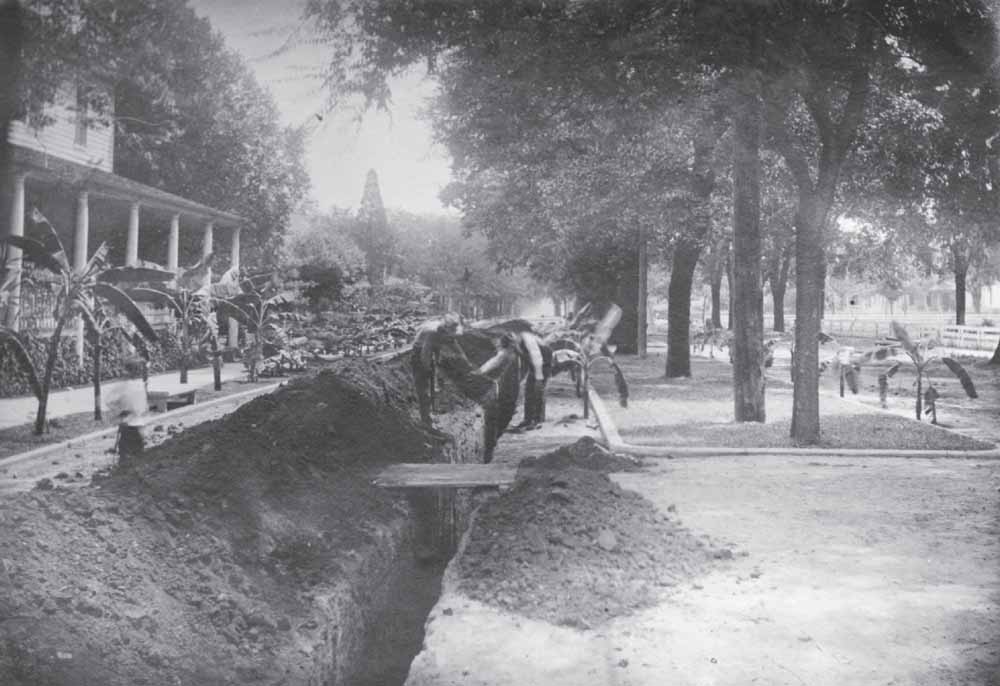

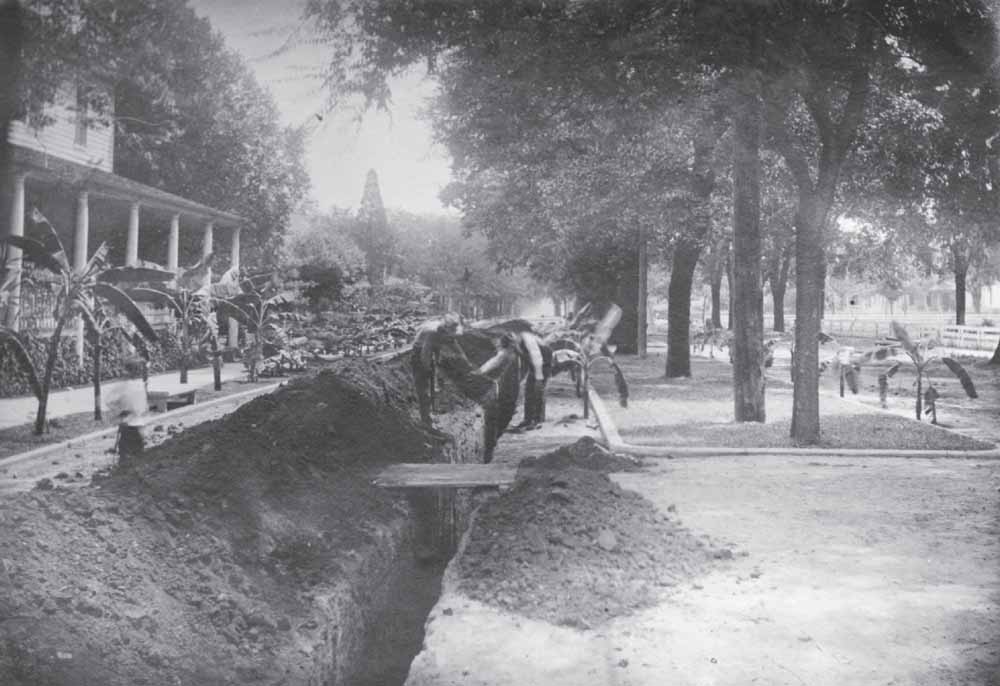

JOHN

J. SEIBELS

RESIDENCE

, JULY

1911.

Excavation for improvements in the city’s gas lines during the midsummer of 1911 disrupted sections of Richland Street, including the 1600 block, as seen in this photograph taken from Pickens Street looking east. Unlike in later years, this stretch at that time featured extensive banana plants and mature street trees, amenities doubtlessly maintained by the Seibels family, whose members owned more than half of the city block. Later, the family would plant a stand of coco palm trees within the median and throughout their yard. Behind the white rail fence to the right, out of view, stands Taylor Elementary School, erected in 1905 as a successor to the Columbia Male Academy. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

MODERNIZING THE

CAPITAL

CITY

, JULY

14, 1911.

Facing east from Assembly Street, an unidentified photographer records gas-service improvements made during the summer of 1911 along the 1100 block of Blanding Street. At right stand Sidney Park CME Church and the Marlboro Apartments, both accessible from the dirt road by a wood walkway spanning an open gutter. In the background, Edwin T. Hendrix’s grocery store, located at 1649 Main Street, faces James Tapp’s Department Store at 1644 Main Street. To the left of the frame, workers mill around a horse-drawn hardtop wagon near a stack of wooden barrels, perhaps belonging to the County Beer Bottling Works that once operated from 1117 Blanding Street at that time. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

FORGING A

NEW

PATH

, SEPTEMBER

23, 1911.

Choked with steel and cross ties, sections of Gervais Street near the State House and west of Assembly Street posed a nightmare for pedestrians and motorists alike for much of 1911 and 1912 while extensive work was performed on the Columbia Electric Railway. Here, a young Columbian poses with his bicycle in front of Susan L. DesPortes’s residence, which then stood on the north side of Gervais Street’s 1300 block. The vehicle parked to his right appears to be a model 1910 Hudson runabout, a make known to have been sold in Columbia at the time by the Gibbes Machinery Company. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

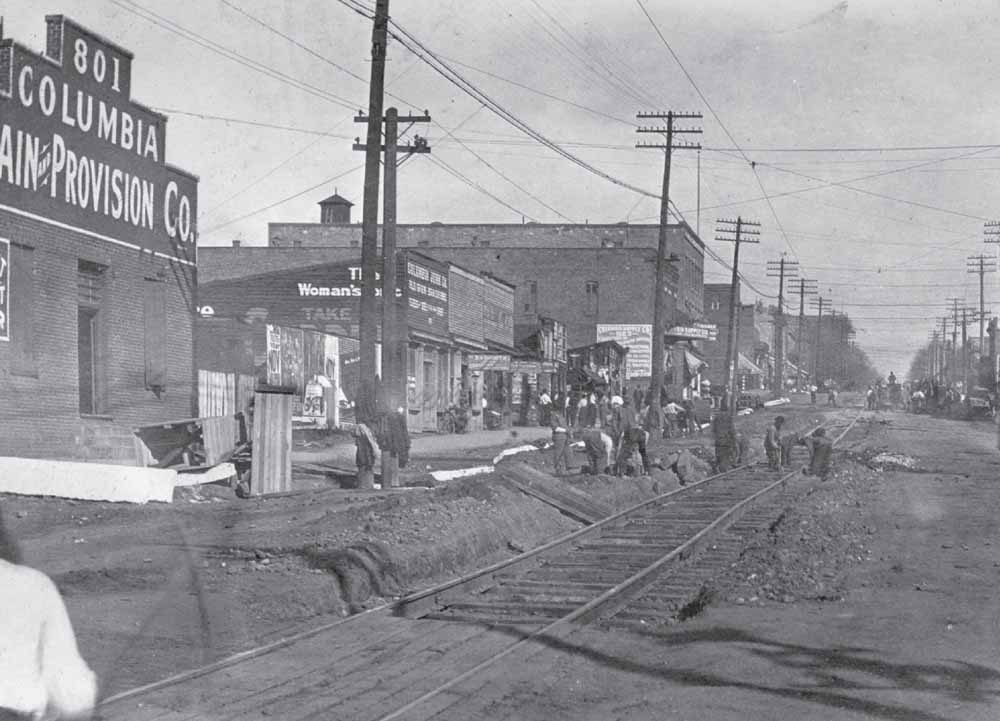

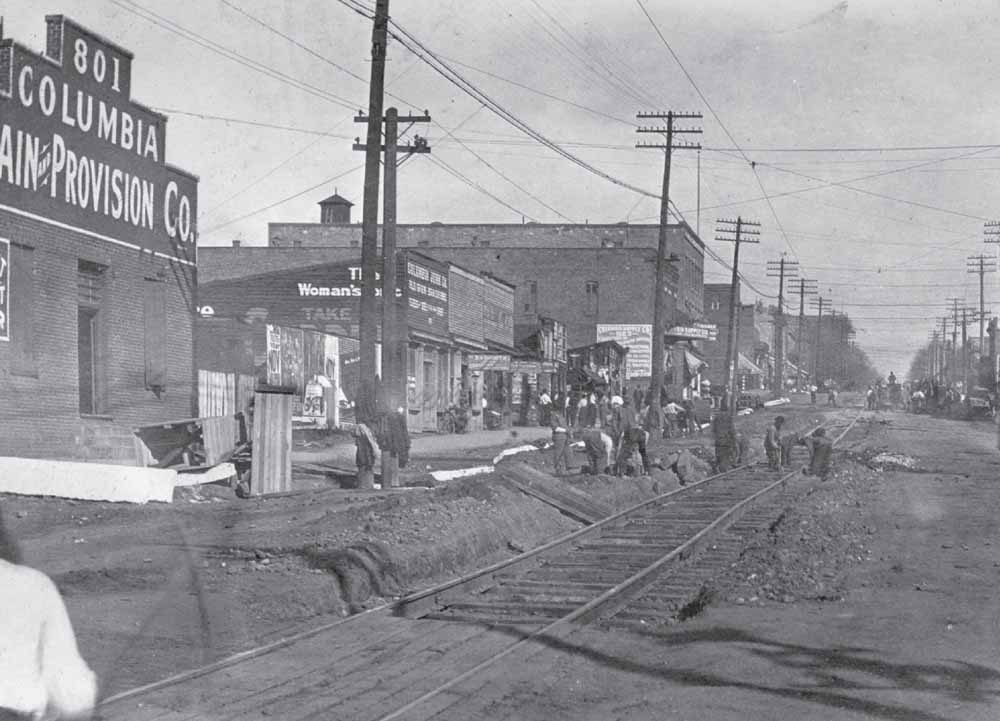

STREET

PAVING

, 800 BLOCK OF

GERVAIS

STREET

, NOVEMBER

11, 1911.

Thousands of vitrified bricks, manufactured by the Augusta Block Company in Georgia, were installed in select areas of the city during work on electric rail and gas service from May 1911 through June 1912. Other road improvements approved by city council a few years later involved Chattanooga’s West Construction Company applying a different, less expensive, paving method to the streets. To accommodate this project, the Columbia Railway, Gas & Electric Company relocated its power lines from the center of each street. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

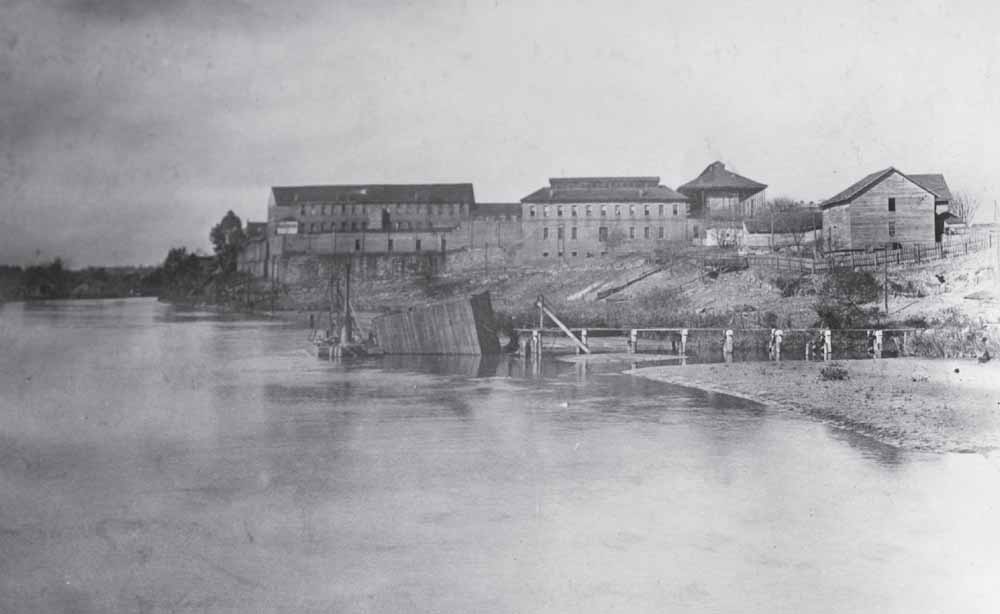

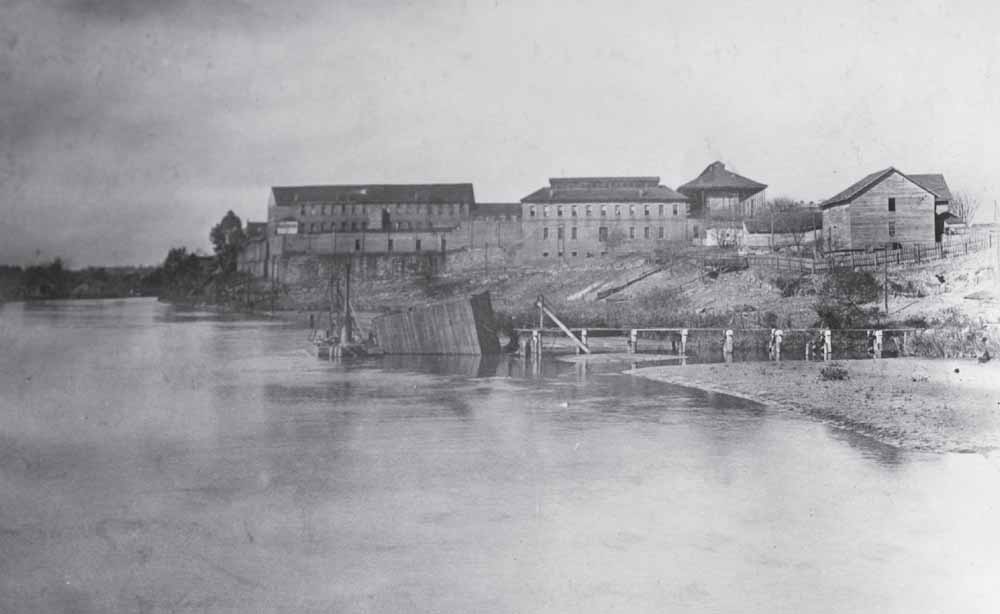

SOUTH

CAROLINA

STATE

PENITENTIARY

, NOVEMBER

18, 1911.

As Columbia developed during the late 18th and 19th centuries, activities that produced waste, noise, or conditions deemed undesirable for downtown were pushed to the periphery of the city limits, where land was less valued. This custom included locating the state prison along the Columbia canal, a move that illustrated planners’ interest in removing criminals from law-abiding citizens while creating a physical barrier as a deterrent to escaping. Established in 1867 during the Reconstruction period, by 1911 the penitentiary consisted of several buildings, including a main cellblock with 250 rooms that each measured five feet wide, eight feet long, and seven feet tall. Other facilities included a hospital, dining hall, workshops, and an area for cultivating vegetables. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

COLUMBIA

WATERWORKS

, DECEMBER

28, 1911.

Busier than Santa’s elves were a few days earlier, workers wrangle a General Electric dynamo from a railroad flatcar with the help of a soot-belching Bucyrus Company wrecking crane. Once unloaded, the power-generating device would be jockeyed into its final location using the log rollers and bridge. These activities were part of improvements being carried out on the canal and at Columbia’s waterworks. The outline of one of the penitentiary’s two-story cell houses, faintly visible behind the leafless trees, indicates this photograph was taken facing south. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

STATE

PENITENTIARY

, JANUARY

11, 1912.

Sharing architectural elements with Charleston’s Citadel campus and the castle-like Parker Building, then standing on the grounds of the State Hospital, the South Carolina State Penitentiary looms over Gist Street during the winter of 1912. The weight and statue of the prison’s crenellated towers contrast sharply with the diminutive wood-frame shotgun-style dwellings lining Blanding Street two blocks to the north. The deep trench in the foreground has been cut in preparation for extending the city’s electric railway up to Irwin Park, a popular green space, which stood adjacent to the city waterworks and featured a zoo. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

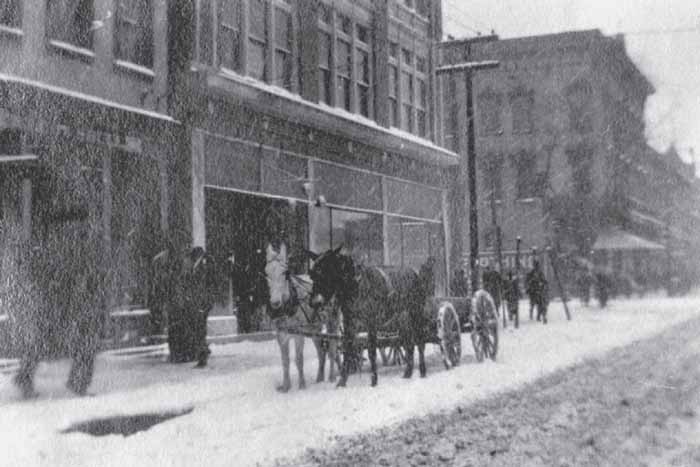

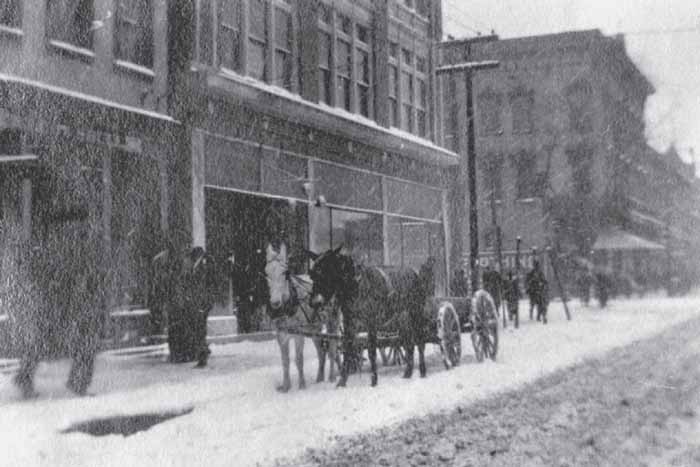

A WINTER

WONDERLAND

, JANUARY

13, 1912.

Despite a daunting 5.9 inches of snowfall and temperatures registering a little above 10 degrees Fahrenheit, intrepid Columbians venture out on foot, by horse-drawn wagon, and aboard the city’s electric railway to conduct business and sightsee at the intersection of Main and Taylor Streets. In the background stand the Columbia Hotel (constructed around 1868, demolished in 1913) and the Bank of Columbia (constructed about 1900). The structure at far right, home to C.H. Girardeau and Company, would be heavily remodeled seven years later as Efird’s department store. (Jeannine Callahan.)

MANSON

BUILDING

, JANUARY

13, 1912.

Taken from the vantage point of Main Street looking southeast toward its intersection with Taylor Street, this photograph illustrates the original appearance of the Manson building, which would, five years later, become the venue where city leaders successfully petitioned for the establishment of Camp Jackson in Columbia in preparation for American involvement in World War I. In the background stands 1556 Main Street, a mixed-use structure from about 1876 that would become a vastly different looking building following a Mid-Century Modern remodeling based on a plan by architect Heyward Singley in 1951. (Jeannine Callahan.)

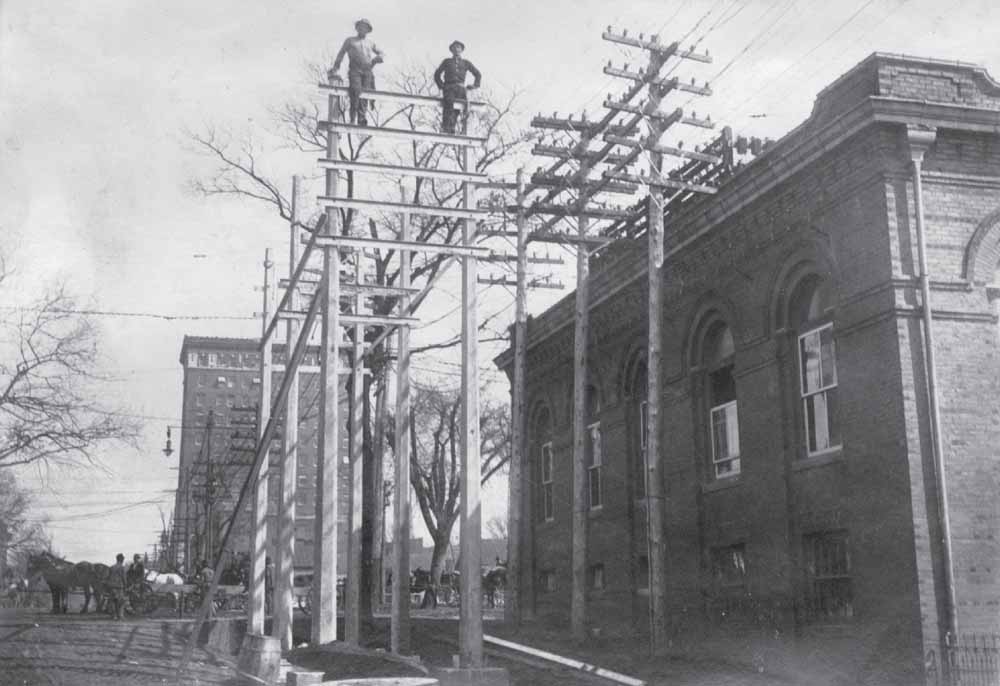

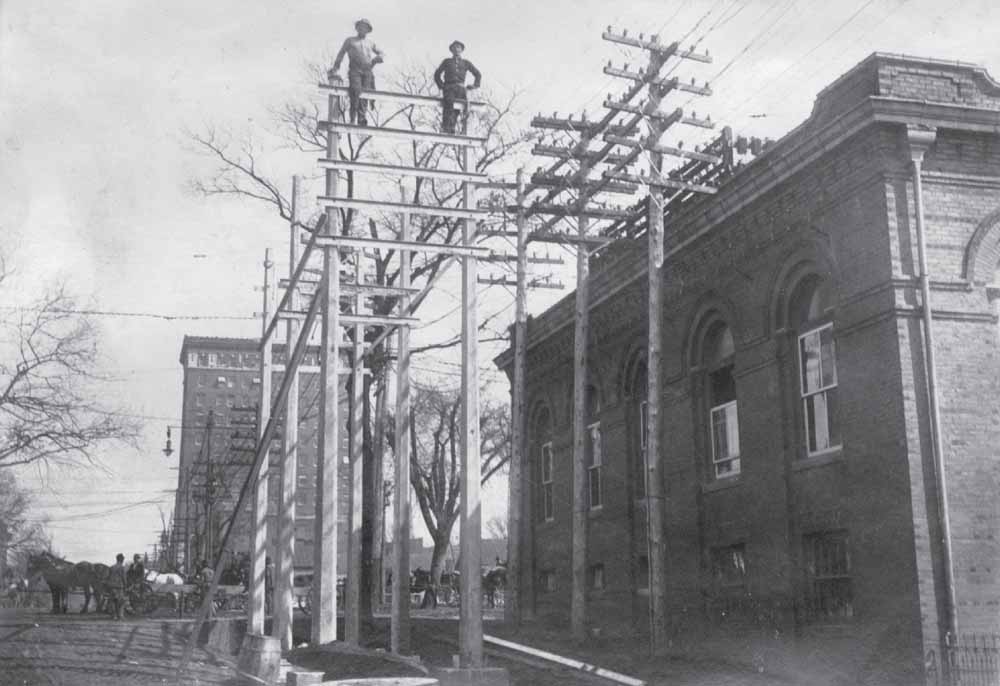

ELECTRIC

RAILWAY

EXPANSION

, FEBRUARY

21, 1912.

Expansion of the Columbia Railway, Gas & Electric Company rail service required enhancing its switching station at 1337 Assembly Street. Here, two construction workers comfortably perch atop a newly completed two-story concrete and steel frame erected for the installation of a more robust electrical system at the southwest corner of Assembly and Washington Streets. Work also involved extending the masonry building on its west elevation through an architecturally sympathetic addition. In the background to the east stands the National Loan and Exchange Bank, Columbia’s first skyscraper, erected almost a decade earlier, in 1903. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

CONVICT

LABOR

GANG

, FEBRUARY

22, 1912.

For decades during the later 19th and early 20th centuries, the State of South Carolina supplied convict labor to private businesses through government contracts. This arrangement was initially viewed as mutually beneficial to the state and those companies that received inexpensive laborers who performed a variety of jobs. The conditions were harsh and often mimicked the practice of hiring out slaves during the antebellum period. However, in this later arrangement, laborers included all prisoners, black or white. By the mid-1920s, arguments arose over the issue of the unfair competition convict leasing had over free labor. Ultimately, this practice was abolished following Progressive-era reforms. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

ARCADE

MALL

, MAY

1912.

Opened on May 9, 1912, less than a month after the Titanic

’s sinking on April 15, the Equitable Arcade at 1332–1334 Main Street was Columbia’s first open-air shopping mall. Designed in the Italian Renaissance style by architect James Brite, who also was responsible for planning the Edwin Wales Robertson residence and the city’s first skyscraper, this $150,000 addition to Main Street became an immediate success. The State

went so far as to call it the “handsomest and most artistic on the American continent.” In a classic example of function trumping form, the property’s architectural accomplishment was diminished by a poorly placed utility pole that bisected the structure’s Main Street facade, as seen in this early image depicting workers completing last-minute tasks at the landmark building. (Jeannine Callahan.)

EDWIN

G. SEIBELS

RESIDENCE

, JULY

28, 1912.

By the early 20th century, the 1600 block of Richland Street was well known for the extensive gardens maintained by the Seibels family. Five years after this photograph was taken, insurance executive Edwin Seibels moved his family out of their eight-room house, seen at right, in order to rent it to Abe J. Silver, the proprietor of Silver’s store, who had relocated to Columbia. After further rentals, the c. 1885 gambrel-roofed residence at 1615 Richland Street was demolished around 1929 to enlarge the gardens of John J. Seibels’s c. 1795 house, standing to the west. The teepee-like structure in the foreground is covering a manhole left open by laborers working in front of the house. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

HABENICHT

-MC

DOUGALL

COMPANY

“MOVING

BILLBOARD

,” C

. 1915.

Christopher Cord Habenicht, Fred Habenicht, and Alex McDougall ran a successful sporting goods store out of 1631 Main Street from 1913 until 1944. The brothers-in-law sold all types of sports equipment in addition to repairing bicycles and firearms. Here, one of the Habenicht family’s cars, “skinned” with advertisements, is parked behind the partners’ store. (Martha Fowler.)

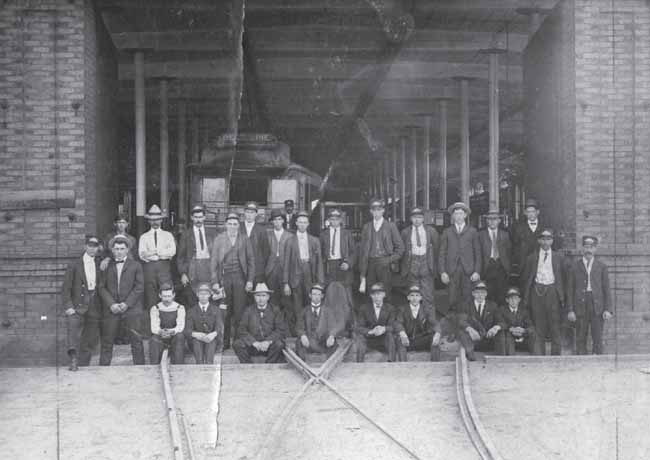

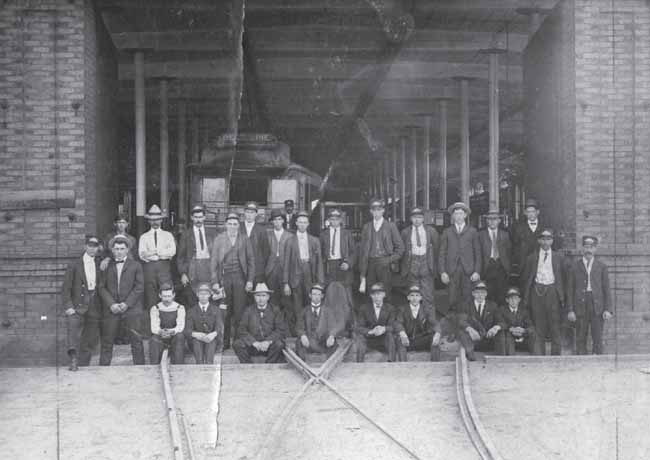

COLUMBIA

STREET

RAILWAY

CONDUCTORS

, MOTORMEN, AND

ADMINISTRATORS

, 1912.

Columbia was propelled into the modern age in 1893 with the establishment of an electric streetcar service that replaced an earlier horse-drawn system. Ultimately, following expansions, the electric railway connected downtown with destinations as far away as Eau Claire and Camp Jackson. Here, employees pose in front of the company’s carbarn, which stood where Main and Rice Streets formerly intersected. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

J.L. HOPKINS

DRY

GOODS

STORE

, 1616 MAIN

STREET, C

. 1912.

Carrying everything from table linens and window curtains to women’s clothing, handbags, and shoes, John Hopkins’s enterprise was one of the many clothing stores in operation along Main Street in the years before World War I. Here, a smartly dressed man, most likely the owner, and two women, one of whom may be his wife, Minnie, stand inside the store’s entrance. Outside, an African American man has rolled back the store’s awning so the display windows, brimming with merchandise, are highlighted for the photographer. By 1932, this structure had been replaced by the W.T. Grant Company’s Art Deco–style five-and-dime store. (Jeannine Callahan.)

SEEGERS

RESIDENCE, C

. 1915.

German immigrant and entrepreneur John Christopher Seegers became one of Columbia’s leading citizens during the 19th century. Seegers, a state legislator, penitentiary board chair, beer brewer, and farmer, moved his family from its Assembly Street home to a larger, finer residence in what is today the Waverly neighborhood. Also called “the Oak Street house” and “the Barhamville plantation,” Seegers’s new address became a favorite destination for family and friends alike. Here, descendants Willie Milne, Annie Alworden, and Bessie Milne (first row, from left to right) and William G. Alworden (standing) pose amid a lush backdrop of potted plants on the property’s porch, which overlooked their beautiful garden. (Frieda Milne.)

LA

MOTTE

RESIDENCE, C

. 1915.

Originally carrying an East Plain Street address, this landmark at 1632 Hampton Street remained a downtown fixture for eight decades. Nestled in a hill overlooking a natural depression to the south, the Neoclassical residence featured, according to The State

newspaper, a “practically private park,” two kitchens, breakfast and dining rooms, 10 bedrooms, a parlor, library, reception hall, servants’ house, laundry, and sleeping porches. As secretary for the State Prohibition Executive Committee, Thomas J. LaMotte and his activist wife campaigned against alcohol during an era in which the state was its only sanctioned distributor. At the Civil War veteran’s death in November 1911, one of his three children, A. Gamewell LaMotte, inherited the property. The younger LaMotte, the cocreator of a detailed map of Columbia for 1895, opened his parents’ home to boarders, offering “delightful fare and fully screened rooms at reasonable rates.” After a succession of two further owners between 1919 and 1924, the property was marketed as “one of the [city’s] best constructed residences . . . suitable for private residence or apartments.” (Paula LaMotte.)

SOUTHERN

RAILWAY

REPAIR

SHOP

, FEBRUARY

1917.

When viewed from its Barnwell Street perspective looking northeast, Southern Railway’s repair facilities looked like a complicated industrial manufactory. In the two-story building at far left, employees operated woodworking machines and upholstered seats. The large structure in the center of the block contained a blacksmith shop, machine shop, and wheel room. A smaller building out of view to the right was used for storage and offices. The site’s whitewashed perimeter wall contrasts sharply with the surrounding dirt roads and bare winter trees. (Montgomery Roads Digital Images, LLC.)

SOUTHERN

RAILWAY

REPAIR

SHOPS

, MARCH

1917.

On February 17, 1865, retreating Confederates destroyed the Charlotte, Columbia & Augusta Railroad facilities in a last act of defiance in the face of advancing Union soldiers. Two years later, in 1867, the facility had been rebuilt and enlarged to include a 12-stall roundhouse for the maintenance of locomotives and train cars. Five decades later, that building (pictured) and others on the eight-acre rail yard located in the 1800 and 1900 blocks of Blanding Street were in use by Southern Railway. By 1925, the company had reduced its number of workers, sending them to newer shops elsewhere. Within a decade, the building had been demolished and the site, formerly abuzz with activity and shrouded in smoke, stood abandoned. (Montgomery Roads Digital Images, LLC.)

A CITY IN THE

MAKING

, SUMMER

1917.

Months of successful lobbying by Columbia’s chamber of commerce led the US Army in May 1917 to announce that it would establish east of the capital city one of 32 proposed cantonment sites for training soldiers. Work on the facility, which signaled the country’s imminent involvement in World War I, began in June, with efforts accelerating each week in order to meet the project’s September 1 deadline. Columbia photographer Walter Blanchard documented the progress of the cantonment’s evolution during the summer. Here, a soldier on security duty stands in the blazing sun as a group of African American laborers gather near one of the site’s employment offices. Around them stand partially completed barracks and support structures, stacks of building supplies, and the means of getting to and from the new post—trucks, automobiles, horses, and railroad tracks. (South Carolina State Museum.)

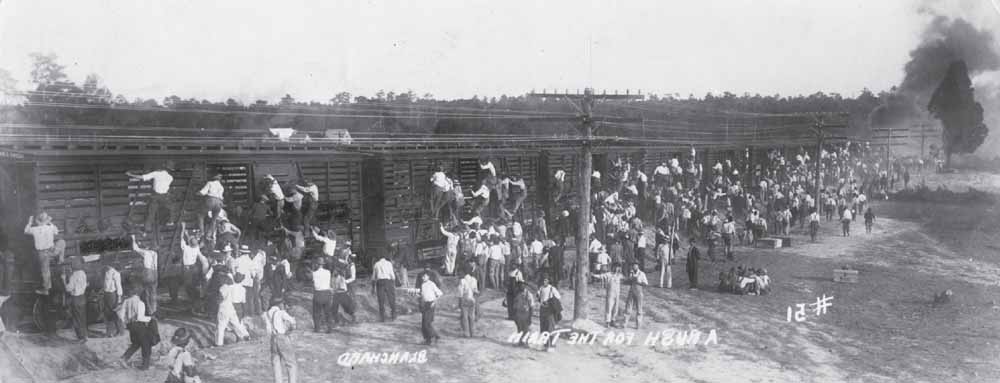

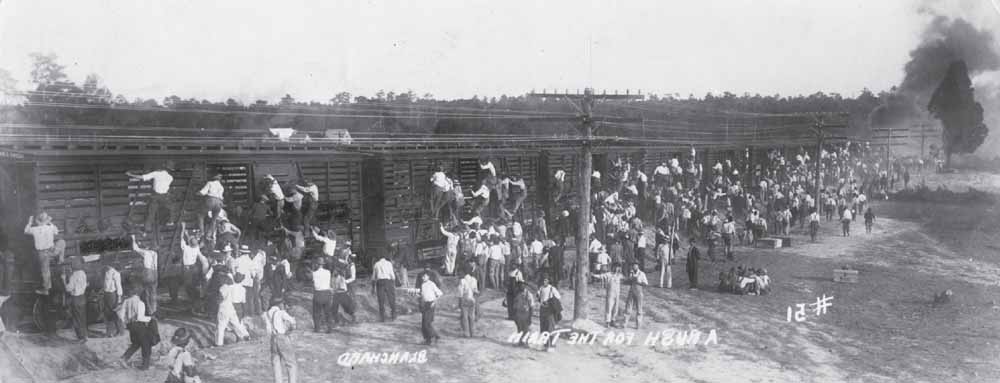

MAKING

TRACKS

, SUMMER

1917.

Following its successful contract bid on June 11, 1917, the Georgia-based firm of Hardaway Construction of Columbus ran help-wanted advertisements in The State

newspaper for the projected 4,000 to 6,000 laborers needed to implement the war department’s massive cantonment five miles east of Columbia. The prospect of erecting accommodations for nearly 30,000 troops led the company to draw workers from throughout the region, as Columbia could in no way supply the personnel necessary to complete the task by the September 1 deadline. Prospective workers were instructed to reply to the advertisements by simply showing up at the worksite and submitting their train ticket stub, the cost of which would be reimbursed following one week of labor. Here, black and white workers clambered into boxcars supplied by the Atlantic Coastline for transport to their worksites. Interestingly, Blanchard’s Studios transposed this image prior to writing its caption. (South Carolina State Museum.)

MANY

HANDS AND

MUCH

WORK

, SUMMER

1917.

Columbia burgeoned with increasingly greater numbers of workers brought in to erect the 120 barracks, complete with kitchens, dining halls, sleeping quarters, reception halls, and hundreds of ancillary buildings required for the Army’s new division. By midsummer, the project’s nearly 2,000 laborers received an unscheduled Fourth of July holiday due to lumber shortages, which, fortunately, were resolved almost immediately with supplies coming from Dorchester County. Here, hundreds of male workers, black and white, young and old, stride past a set of railroad tracks recently laid for the easy transport of personnel and materials to the cantonment work sites. Above them hang electrical lines, just one of the infrastructural improvements, which also included water service, offered by the City of Columbia in support of this unprecedented federal project. (South Carolina State Museum.)

PUTTING

FACES ON

NUMBERS

, SUMMER

1917.

While a sentry brandishing a bayonet-fitted rifle keeps order, a large group of workers pause from their various jobs at the cantonment site. Most carry either a slip of paper or wear a round disk featuring numbers, which presumably was a means of identification for each contracted laborer. By the time the military facility was opened officially, these men, and others, had toiled endless hours in the hot Carolina sun building a city where before little had stood. Their efforts set the foundation for what would become Camp Jackson and, after the advent of World War II a generation later, Fort Jackson, one of the nation’s largest Army training facilities and a major force that continues to shape Columbia. (South Carolina State Museum.)

HABENICHT

PARADE

ENTRY, C

. 1919.

Sporting whitewashed tires, the South Carolina state flag, and bunting and laurels, Bertha Howe Habenicht and Christopher Cord Habenicht Jr.’s stylish roadster makes for a festive entry in what may have been the Armistice parade of 1919, chronicled by a Blanchard Art Studios photographer. The exact location of this image remains uncertain. (Martha Fowler.)

HOME

SWEET

HOME

, 1921.

In 1913, Joel A. Smith Sr. and his wife, Beulah, built an impressive two-story residence at 720 Queen Street in the growing suburb of Shandon. There the couple and their six children maintained a small farm consisting of a barn, chicken coop, pigeon flyer, and stables where they kept a horse and carriage. In 1921, the property received a unique addition—a miniature bungalow playhouse with a Burriss metal shingle roof, screen door, and front porch. Built by Smith’s company, Palmetto Lumber, the diminutive wood structure, loaded onto the rear of a c. 1917 model Republic truck, was entered in a Columbia parade. The company’s handiwork was of such high quality that the playhouse still stands nearly a century later. (Smith family.)

COLUMBIA

POLICE

DEPARTMENT

, 1922.

With the barred windows of the Richland County jail visible in the far background, six members of Columbia’s 50-member police force pose in front of the city’s courthouse and jail, located in the 1400 block of Lincoln Street. Most of its members wielding wooden batons, this all-white force was charged with maintaining the peace in a city that had grown to 37,525 citizens by the time this image was taken by photographer John A. Sargeant. Trousers bloused in riding boots, the motorcycle officer at far right leans against what appears to be a 1920 model Harley Davidson motorcycle. (Historic Columbia archives.)

CHICORA

COLLEGE

STUDENTS, C

. 1923.

From 1890 until 1930, the former Hampton-Preston estate teemed with women, many of whom would be the first of their generation to receive college degrees. After 25 years as the College for Women, the four-acre campus, bounded by Blanding, Pickens, Laurel, and Henderson Streets, became home to Chicora College, which moved from Greenville to Columbia in 1915. Both Presbyterian schools offered a curriculum that included languages, fine art, various sciences, mathematics, music, religion, and business. When not studying, students engaged in extracurricular activities, including playing sports, participating in clubs, and spending time in their dormitory rooms and the surrounding gardens. (Historic Columbia archives.)

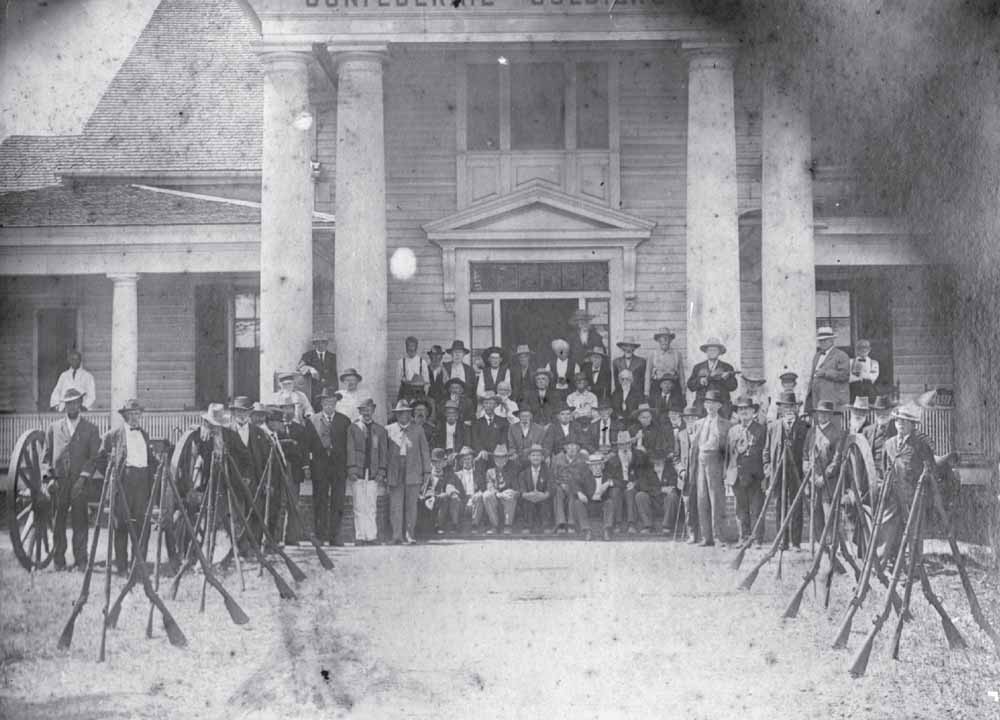

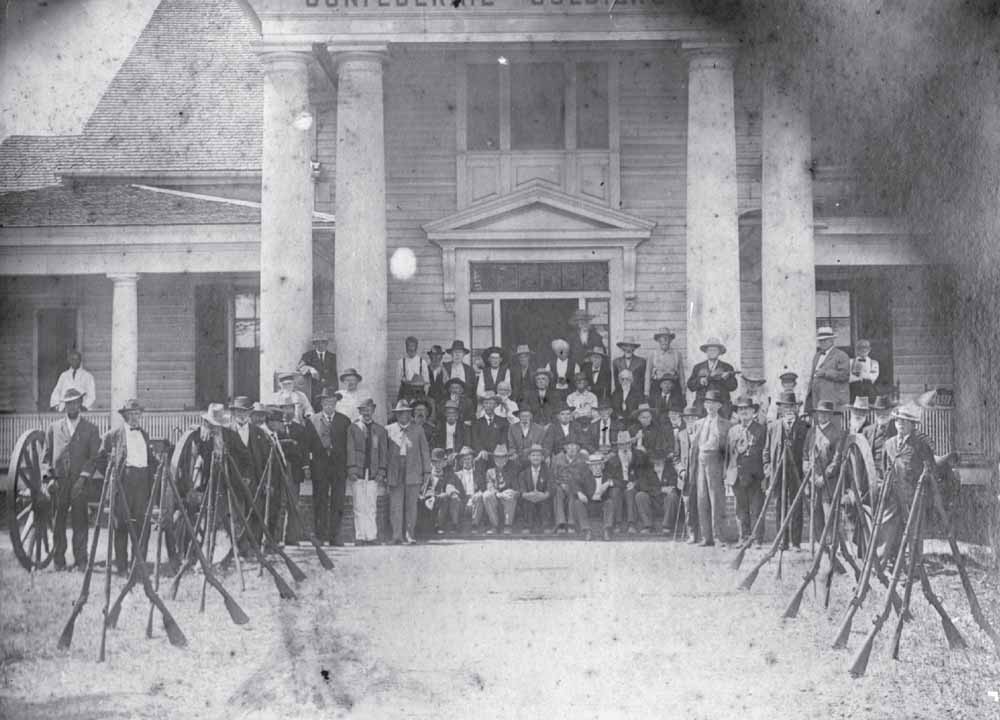

SOUTH

CAROLINA

CONFEDERATE

SOLDIERS

’ HOME, C

. 1925.

With rifles and muskets stacked and flanked by a cannon and its limber, a group of white-haired former rebel soldiers assembles in front of the state’s home for Confederate veterans at 1417 Confederate Avenue. Established in 1909, the retirement facility could accommodate 70 veterans at one time. The home later expanded its mission to accept veterans’ widows and daughters, the last of whom were relocated in June 1957 when the site was closed due to budgetary reasons. Deteriorated and considered unnecessary, the mansion was demolished six years later, in June 1963. (Historic Columbia collection, HCF 1969.70.1.)

PRESBYTERIAN

THEOLOGICAL

SEMINARY, C

. 1925.

Though intended to be a fashionable residence for English merchant Ainsley Hall and his lower Richland County wife, Sarah Goodwyn, the mansion designed by architect Robert Mills around 1823 has experienced only institutional use throughout its existence. Following Hall’s untimely death and a subsequent court battle by his wife over survivorship claims, the Presbyterian Synod of South Carolina and Georgia purchased the handsome columned structure and its four-acre tract for use as its theological seminary. Opened in 1830, the institution weathered economic downturns and war while producing many graduates who assumed national prominence in their field. Following the seminary’s move to Decatur, Georgia, in 1928, the property at 1616 Blanding Street hosted other religiously based schools, including Westerveldt Academy (1934–1937) and Columbia Bible College (1937–1958). (Both, Historic Columbia archives.)

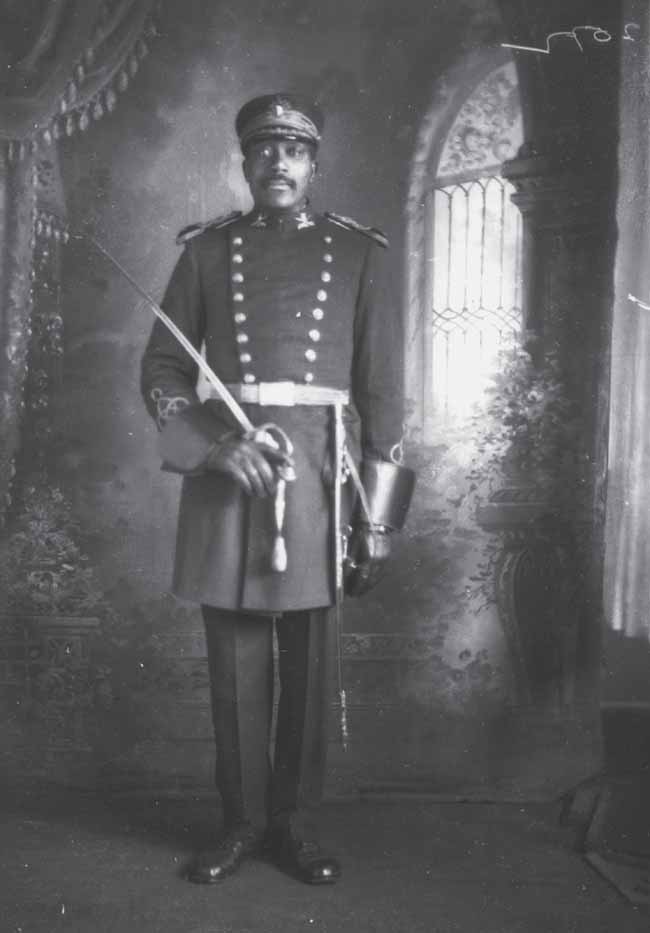

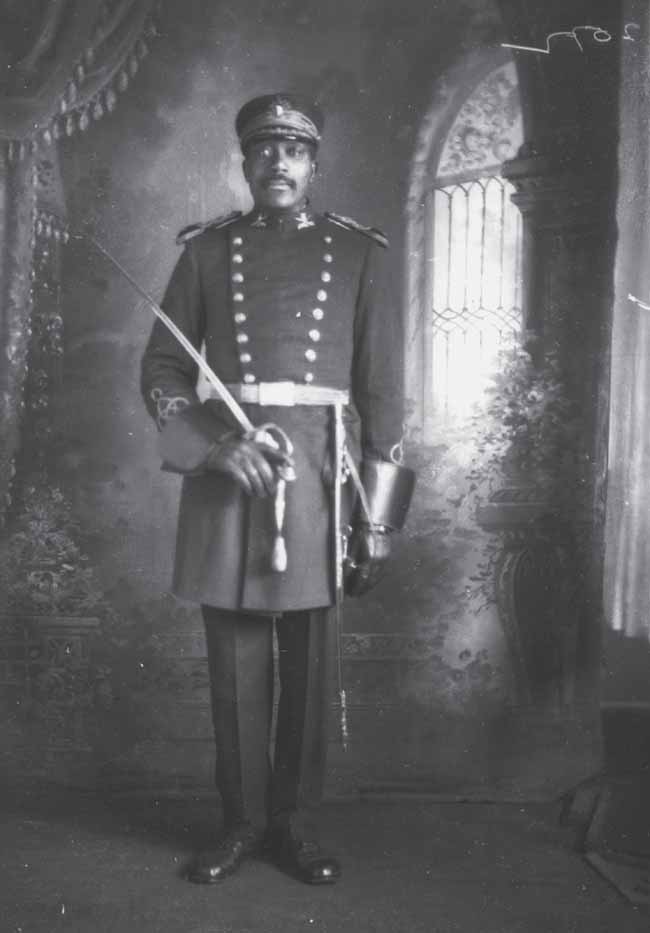

WILLIAM

M. ATKINSON, C

. 1925.

From his arrival in Columbia in 1920 until his death in 1936, photographer Richard Samuel Roberts chronicled members of the capital city’s African American community to an unprecedented extent. Roberts’s ability to capture the humanity of each person markedly contrasted with prevailing social norms that sidelined the individual character of black citizens in popular media. The photographer’s subjects ranged in age, gender, and profession. In this instance, W.M. Atkinson, a local Knights of Pythias lodge member also known as Colonel Atkinson, was photographed in his fraternal order’s military-inspired uniform. The order’s “Uniform Rank” attire bore a reasonable similarity to the uniform Atkinson wore decades earlier as a member of the Governor’s Guards, a distinguished African American militia unit disbanded in 1902. (South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia. From A True Likeness: The Black South of Richard Samuel Roberts: 1920–1936

; courtesy of the estate of Richard Samuel Roberts, by permission of Bruccoli Clark Layman, Inc.)

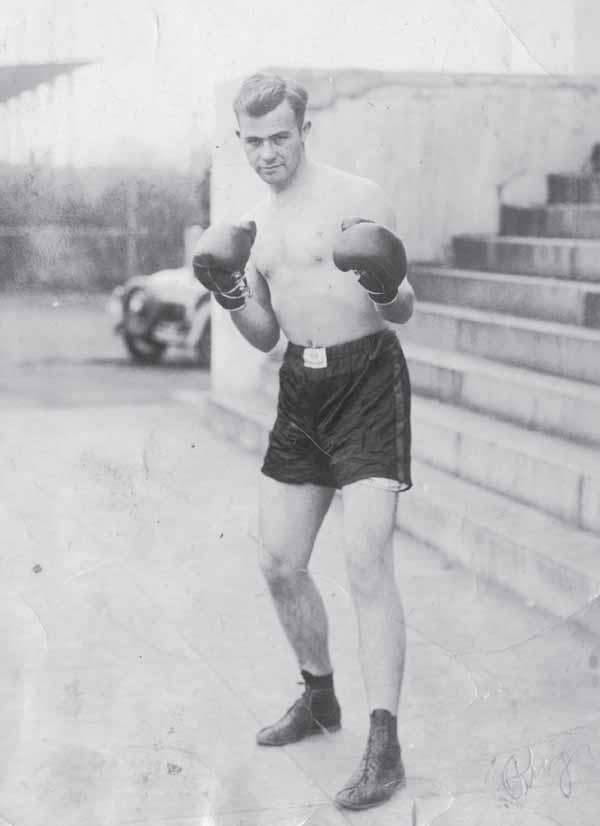

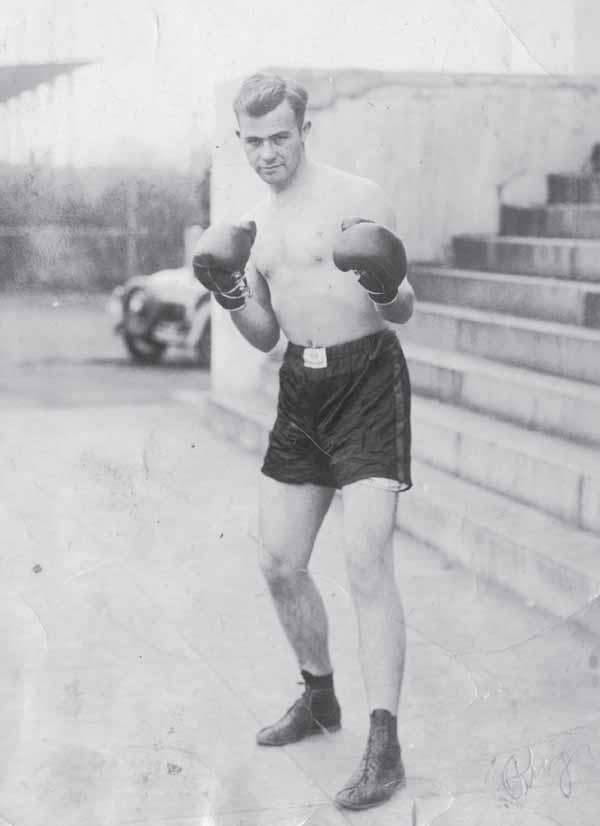

WILLIAM

OSCAR

CALLAHAN, C

. 1928.

Greenville native William “Bill” O. Callahan strikes a formidable pose while at the University of South Carolina. Behind the student boxer stand the front steps of Longstreet Theater, then used as a gymnasium, and the university’s athletic fields, today the location of Thomas Cooper Library. Following graduation, he married, remained in Columbia, and built a home at 2808 Forest Drive in 1936. A colonel in the Army Air Corps during World War II, Callahan was appointed Columbia’s postmaster in 1961, a position that allowed him to influence the construction of the city’s main post office building in 1965. (Jeannine Callahan.)

COTTONTOWN

, 1926.

From the 1890s through the end of the 1920s, Columbia experienced considerable growth through suburbanization. Eager developers established a host of new neighborhoods, including Elmwood, Waverly, Shandon, Melrose Heights, Oak Lawn, Wales Garden, Hollywood, Rose Hill, and Bellevue, popularly called Cottontown for the warehouses that formerly stood in the district just over the city’s northern limits. Among Bellevue’s residents was the Manini family. With Craftsman-style houses on Summerville Avenue and the family’s Buick sedan as a backdrop, Mary and Mose Manini (far left) pose with their daughters Peggy (infant) and Gloria, accompanied by Anastasia Manini (visiting from Italy) and an unidentified man in 1926. (Peggy Manini Janicki.)

AMERICAN

LEGION

PARADE

, JULY

24, 1930.

Columbia photographer John A. Sargeant took full advantage of his location in the official reviewing stand when he documented a midsummer celebration as it made its way through the 1600 block of Main Street. Among the five bands participating was the Parris Island Marine Corps marching band, shown here as it passed in front of Efird’s department store. Other attractions included National Guardsmen from South Carolina and Florida; veterans from World War I, the Spanish-American War, and the Civil War; and a float that featured a .30-caliber machine gun firing blanks. Flags, suspended from the electrical lines of the recently defunct electric railway service, added to the spectacle that attracted hundreds of interested onlookers. (Richland Library.)

SIMONS

BODY

WORKS, C

. 1930.

From 1929 until 1940, Robert Lunce Simons operated a workshop at the intersection of Washington and Gates (Park) Streets in Columbia’s “black downtown,” a thriving area west of Assembly Street featuring stores, professional offices, businesses, and residences. Applying his skills as a blacksmith and wheelwright to increasingly popular and numerous automobiles, Simons, a Tuskegee Institute graduate and disabled veteran, specialized in fabricating custom bodies and repairing damaged vehicles. In this image by well-known African American photographer Richard Samuel Roberts, four men pose beside a Dupre Motor Company truck featuring a body built in their shop at 928 Washington Street. In the background, to the left, stands the House of Peace Synagogue. (Richard Samuel Roberts Collection, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia.)

ANDREWS

GARAGE, C

. 1931.

With a Series 116 Dodge Tourer from about 1924 for a centerpiece, Andrews Garage employees pose in front of their Sumter Street location shortly after owner Robert C. Andrews moved his five-year-old business from its original location at 1315 Taylor Street. Well-situated downtown, the business now at 1513 Sumter Street later moved to two separate Harden Street sites, one near Benedict College and the other in Five Points, south of Gervais Street. (Matt Riley.)