The audience dispersed after the entertainments in the Rotunda, free to amuse themselves until reconvening for the evening ball. New arrivals filled the town, met by unceasing rain, including many of London’s literary set “testifying their reverence for the great Father of the English Drama.” Many of them were guests whom Garrick would be pleased to see, including George Colman, the manager of Covent Garden; John Hoole, a translator and civil servant; and Hugh Kelly. Others he was less sure about. Among them was his future biographer, Arthur Murphy, currently an enemy with whom he feuded often, usually over Garrick’s refusals to stage Murphy’s plays.

Neither would Garrick look favorably upon the unwholesome frame of William Kenrick, who, despite being so devoted to Shakespeare that he had named his eldest son William Shakespeare Kenrick, was considered an oily blot on the literary landscape. A disagreeable degenerate and failed poet, Kenrick set his hand to various forms of literary jobbing, including an English translation of Rousseau’s Julie, in which he arbitrarily changed Julie’s name, and a moralizing guide to female etiquette entitled The Whole Duty of a Woman; or, A Guide to the Female Sex, from the Age of Sixteen to Sixty. These days he courted infamy by sniping at authors of note—among them Samuel Johnson, whose edition of Shakespeare he had attacked noisily in the Monthly Review as ignorant and inattentive, characterizing Johnson’s relationship to Shakespeare as that of “a fungus attached to an oak.”

Garrick’s worst nightmare, however, was lodged at the Bear Inn, Bridgetown, the hostelry a mile outside of town that had taken in thirty beds to handle the Stratford overspill and whose cellar stored Domenico Angelo’s gunpowder. The Bear hosted two men who had traveled to Stratford purely for the pleasure of watching Garrick fail, as so many predicted he would. They were Charles Macklin, Garrick’s former acting tutor, and a fellow theatre manager named Samuel Foote.

After nurturing Garrick’s talent and being so quickly overshadowed, Macklin had resorted to ridiculing what his protégé had become. “The whole art of acting,” he said of Garrick, “is comprized in—bustle! ‘Give me a Horse! —Bind up my wounds! —Have mercy Jesu!’ —all bustle! —every thing is turned into bustle!” Worse still, he believed that Garrick had conspired to have him fired from Drury Lane in 1743 after Garrick had joined the company at a salary of £500 a year just as the other actors were refusing to work until the then manager, Charles Fleetwood, increased their pay. Under Garrick’s leadership, the actors presented a united front, refusing to sign new contracts unless improved terms were agreed for all. An understanding was reached, but only on condition that Macklin, a source of “intractable, unreasonable Obstinacy” (according to Fleetwood), was dismissed. With some reason, Macklin believed that his expulsion had been orchestrated by Garrick and sought to avenge himself by organizing hissing and catcalls from the pit, a ploy that failed when Fleetwood hired “banditti” to menace the protestors. Defeated, Macklin declared himself Garrick’s “bitterest enemy” and, reduced to teaching oratory and elocution to tyrannized schoolboys, clung to his resentment for more than two decades. Hungry for any humiliation or embarrassment that he could use to attack his adversary, he kept his pencil ever sharpened.

While Macklin might be yesterday’s man, his companion, Samuel Foote, was very much a man of the moment. At the height of his powers as one of the most popular and feared impresarios of the age, Foote was instantly recognizable for his broad belly, wooden leg, and a verbal tic that went “hey-hey-what.” He was a ruthless and uncompromising satirist, unafraid to be cruel or break friendships rather than miss the chance to make a good joke. Garrick knew this better than anyone, and while the two had been uneasy friends for years, they regularly exchanged barbs from the stage, although it was no secret that Garrick lived in fear of Foote’s ridicule and would timidly try to appease his antagonist before the stakes rose too high. Samuel Johnson considered Foote not only to possess “extraordinary powers of entertainment” but to have an almost feral wit. “Foote is the most incompressible fellow that I ever knew,” he told Boswell. “When you have driven him into a corner, and think you are sure of him, he runs through between your legs, or jumps over your head, and makes his escape.” Foote was a risk taker who had spent his career skirting the law, expertly evading the 1737 Licensing Act by charging people for a dish of chocolate or advertising his performances as if they were pictures at an exhibition, or dispensing with actors altogether and employing life-size puppets.

The recent loss of his leg had only made Foote more powerful. The accident had occurred during a hunting party with his friends Lord and Lady Mexborough at Methley Hall, their house in Yorkshire. The party was composed of boisterous aristocrats, most of them a decade younger than Foote, including Boswell’s loathed Duke of York, who had bet the actor that he could not ride a particularly querulous horse. Foote, out of his element but profoundly competitive, took the bet and was thrown, suffering a severe concussion and fractured leg that had to be amputated above the knee. To compensate, the Duke arranged for Foote to receive a patent to run the Haymarket theatre during the summer months. With his talent for showmanship suddenly legitimized, Foote became quickly rich, although this did nothing to diminish the delight he took in baiting Garrick. As he had already told the papers, he cared little for Shakespeare and had come to Stratford purely for the purpose of amassing research for a production he intended to call Drugger’s Jubilee (after Able Drugger, a character in Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist and one of Garrick’s best-known roles), a mocking dismantling of Garrick’s pretensions that he intended to have on stage even before Garrick had returned from Stratford. This was the reason, he told anyone who would listen, that Garrick had conspired to make sure he lodged at the Bear Inn atop Angelo’s gunpowder—David Garrick was plotting to have Samuel Foote blown up.

The rain fell hard as Foote and Macklin joined the crowds about town to experience the full extent of the profiteering taking place in the name of Shakespeare. “It has cost me above fourteen pounds since I left London, for the pleasure of being grossly affronted, and the satisfaction of being half starved,” wrote a correspondent for the Whitehall Evening Post. “I love Shakespeare’s memory very well, but I cannot bear to be famished out of deference for his character: nor do I see why, because the good people of Stratford are his townsmen, they should be allowed to plunder their well-meaning fellow subjects with impunity.”

One guesthouse was charging its patrons eighteen pence each time they used the privy. Nonresidents were required to pay a shilling. The price to tie a horse was half a guinea, the same amount it cost to borrow a coat. One guest was charged a shilling for bringing his dog and nine pence for washing his handkerchief. Foote asked one man the time, only to be told that the answer would cost him two shillings. He readily handed over the money “for nothing more than having it to say that I have paid two shillings for such a commodity.” The timekeeper obliged him with the hour but not the minute, informing him that minutes cost extra. With the rain setting a premium on keeping dry and clean, the operators of sedan chairs were able to name their price. A chairman named Larry O’Brien, claiming descent from the ancient kings of Munster, was asking half a guinea for a journey of one hundred yards: “I’ll give you a crown, you unconscionable rogue,” said his passenger, who was also Irish. The account, published in the Whitehall Evening Post, continued:

“Long life to your honour, you know it is Jubilee time,” replied O’Brien.

“I’ll give you six shillings,” said the man.

“The sweet Jasus bless you honour, don’t be so hard on your own countryman,” said O’Brien.

“I won’t give a farthing more than the three half crowns.”

“What time shall I call for your honour?”

Despite the extortion, Jubilee favors continued to sell well, as did Jubilee handkerchiefs in white and red, and the gold, silver, and copper medals styled after the one worn by Garrick. Sales of ribbons were accounted at “a thousand pounds,” and of medals “it is conjectured treble that sum, even upon a moderate computation,” which some in this time of economic depression and national unrest found excessive: “Yet we are distressed all this time our trade is utterly gone, and we are taxed up to the very verge of destruction.” At least Musidorus could record one touching “instance of conscience,” when the cook in his lodgings sent out the intestines of the chicken he had ordered arranged next to the meat, “and told us, that as her Mistress charged enough for every thing, it was but reasonable we should have our property entire.”

Commemorative handkerchief. © Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

Of all the souvenirs, none were as profitable as relics from the mulberry tree. Following the Reverend Gastrell’s felling of the tree in 1756, much of the timber had been sold to the Corporation of Stratford while another section had been purchased for firewood by Thomas Sharp. Sharp retained a portion in his shop in Chapel Street for parceling out into knickknacks “of Stand-dishes, Tea-chests, Inkhorns, Tobacco Stoppers, etc.” He had begun to sell mulberry relics as early as 1756, earning at least three hundred pounds by turning out chairs, toothpick and needle cases, ladles, nutmeg graters, and other kinds of Birmingham-inspired toy work. A third parcel of wood had gone to a carpenter named George Willes, who had sold four raw lumps of it, along with a letter proclaiming its authenticity signed by William Hunt and John Payton, to David Garrick in 1762; Garrick used it to decorate an ornate chair designed by his friend, the artist William Hogarth. Given the amount of trade that had already taken place since Gastrell’s act of vandalism, it seems unlikely that much of Shakespeare’s original tree was left by 1769, yet a remarkable amount of it was still offered up for sale. As Domenico Angelo’s son, Henry, reflected in later life, “It is asserted that there are ten or a dozen skulls, at least, of the same holy saint to be seen at different convents in various parts of Spain; and it is supposed, that as many mulberry trees, within the last half century, have been converted into ink-stands, tobacco-stoppers, and various turnery ware, all as veritably relics of this identical stump.”

An example of the ubiquitous trade in mulberry souvenirs—a tobacco stopper, used to pack a pipe. © Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

For the Jubilee’s detractors, the mulberry offered a perfect metaphor for the overheated absurdity of Shakespeare mania. Over the summer, the Public Advertiser published a series of pieces, very possibly the work of George Steevens, that were written from the perspective of the tree itself and recorded the many and repeated humiliations it had endured. “Had the keepers of my dungeon been contented only with giving me away to others,” complained the tree,

I should have found in some place of my soul a drop of patience; but to be prostituted to their own convenience, to be converted into tobacco-stoppers, handles to knives and forks, and nutmeg-graters, is more than I can bear without expostulation. Not a girl in our town but carries about her a tooth-pick, knitting-sheath, or comb-case fabricated out of my ravaged entrails. Some of the principal wool-combers have cards composed out of my very heart; and one of the most luxurious of my townsmen (an apothecary by professions) to prove his fundamental regard to Shakespeare, has had a branch of me hollowed into a pipe for the most degrading services of the human body.

(One pauses to wonder whether Shakespeare, whose teeming mind engendered worlds, might ever have imagined that a strip of his sapling would be one day used to administer enemas.)

Steevens’s pieces not only gave voice to the tree, they animated it too. One of his possible pseudonyms, “Speculator,” offered “a very summary Account of the many Hoppings, Hobblings, Jumpings, Skippings, Caperings, Frisks, Curverts and Vagaries, which this sensitive plant is obliged to exhibit every Day,” having claimed to have witnessed as much in London’s Spitalfields, where the much maligned poet George Keate owned a number of properties. Ever since Keate “first drew the Mulberry tree of Stratford hither,” he wrote,

the whole Place has been an absolute Fair. All Trade is in a Manner suspended and the Efforts of industrious Labour are postponed till the Violence of eager Curiosity has been gratified to the full. The Carpenter’s Yard in which this venerable Relic is preserved, is a very large one, and capable of holding a thousand People at once; yet such is the general Impatience that many have absolutely attempted to untile the Shed where it has taken Shelter, by getting upon the Wall that they may enjoy a Peep at it a few Minutes before it comes to their Turn.

The crowds, he reported, had started to grow, “especially since a Discovery has been made that the old Trunk will put itself into Motion at the bare Recital of a few of Mr. Keate’s Verses, from any Mouth as well as his own.” Once this miracle had been revealed, no one would leave it alone:

The Tree is sometimes most cruelly harassed as half a Score People surround it, reciting all at once. The Wood itself appears, during the Ceremony, in the most uneasy Situation possible, as it can hardly move in Obedience to a Couplet before it is summoned another Way by a Stanza. The Strength of a well-conducted Metaphor jerks it seven or eight Yards Westward, from which Place it is no less violently borne back by the Current of a Simile. At a Compound Epithet, however, it seems ready to jump out of it’s Bark, and the slightest Allusion to Shakespeare himself has sufficient Power over it to make it follow the Reciter round the whole World.

In a similar vein, “Desqueeze-Oh!” described the tree’s reaction as Garrick rehearsed his ode in Stratford’s Town Hall, telling the readers how, as he came to the end of the first stanza, “the withered Mulberry began to move. Before the Conclusion of the Ode, the venerable Tree was dancing upon one End thro’ the dedicated Hall.”

Such barbs sought to place Garrick’s celebration on a par with the vulgar fairground sideshows that sprang up around the fringes of the Jubilee, and highlighted the way in which the veneration of relics replaced any sensible discussion of literary merit with slack-jawed wonder. They were also a joke about the power of poetry to “move” its audience, aimed both at Keate’s inexpert verse and the scale of presumption implied by Garrick’s ode. Another article added the specter of religious heterodoxy to the list of complaints, claiming that part of the timber had been graffitied and left in a lumber room in the old town hall “among mice-gnawn records, mouldy buckets, and tattered ensigns,” and an “old figure of the Pope” that had been rescued from a Protestant bonfire by a former mayor who practiced Catholicism. This was a pointed detail, as not only was Stratford known as a center for recusant Catholics in the sixteenth century—including, potentially, Shakespeare’s own family—but by associating the mulberry with the remnants of Romish religion, it implied again that Garrick was guilty of the idolatrous worship of false gods. It did not help that since Garrick’s announcement of the Jubilee in May, Clement XIV, the newly crowned pope, had declared that a religious jubilee for all Catholics would begin in March of the following year. The coincidence did not pass unremarked, and certainly no one present at the Rotunda as Lord Grosvenor reverentially raised a mulberry cup, treating the “blest relic” as if it were a chalice filled with communion wine, would have failed to appreciate the parallel between this and Catholic rituals, especially Mass. It was also well-known that Eva Garrick was a practicing Catholic who attended Mass her entire life, and for those who sought to ridicule her “mitred” husband as “Saint Mulberry’s Priest,” serious questions remained.

As the sun began to set, bonfires were lit and Domenico Angelo and the sulfurous Clitherow set to work illuminating the transparencies that had been placed in the windows of the birthplace and of Town Hall. These transparencies were paintings on gauzy canvas whose large frames covered the windows; when lit from behind, they shone through with brilliant colors. Hanging over the window in which Garrick had decided that Shakespeare had been born was a painted device showing the sun struggling through the clouds “in which was figuratively delineated the low Circumstances of Shakespeare, from which his Strength of Genius rais’d him, to become Glory of his Country!” The illuminations covering the five front windows of the Town Hall were even more ambitious. In the center was a full-length figure of Shakespeare capturing a Pegasus in flight above the inscription “Oh! For a muse of fire.” To his left were Falstaff and Pistol from The Merry Wives of Windsor, while to his right was Lear in the act of execrating his daughters, and Caliban drinking from Trinculo’s keg from The Tempest. A hundred colored lamps shone through these canvases, which Garrick had modeled on ones created by the Royal Academy to illuminate its buildings two months earlier in honor of the king’s birthday. Those transparencies, representing painting, sculpture, and architecture, were by the artists Giovanni Cipriani, Benjamin West, and Nathaniel Dance, respectively. Garrick admired the effect and, hoping to save money, asked his friend Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first president of the recently founded academy, whether he could borrow them. Reynolds insisted he “could not part with them,” so Garrick turned to the scene makers French and Porter to build some of their own. As they were being built, it dawned on him how usefully these might be used onstage to effect instantaneous scene changes, in which the image seen by the audience would miraculously transform depending on whether the gauze was lit from the back or the front, an effect that would come to be used often at Drury Lane.

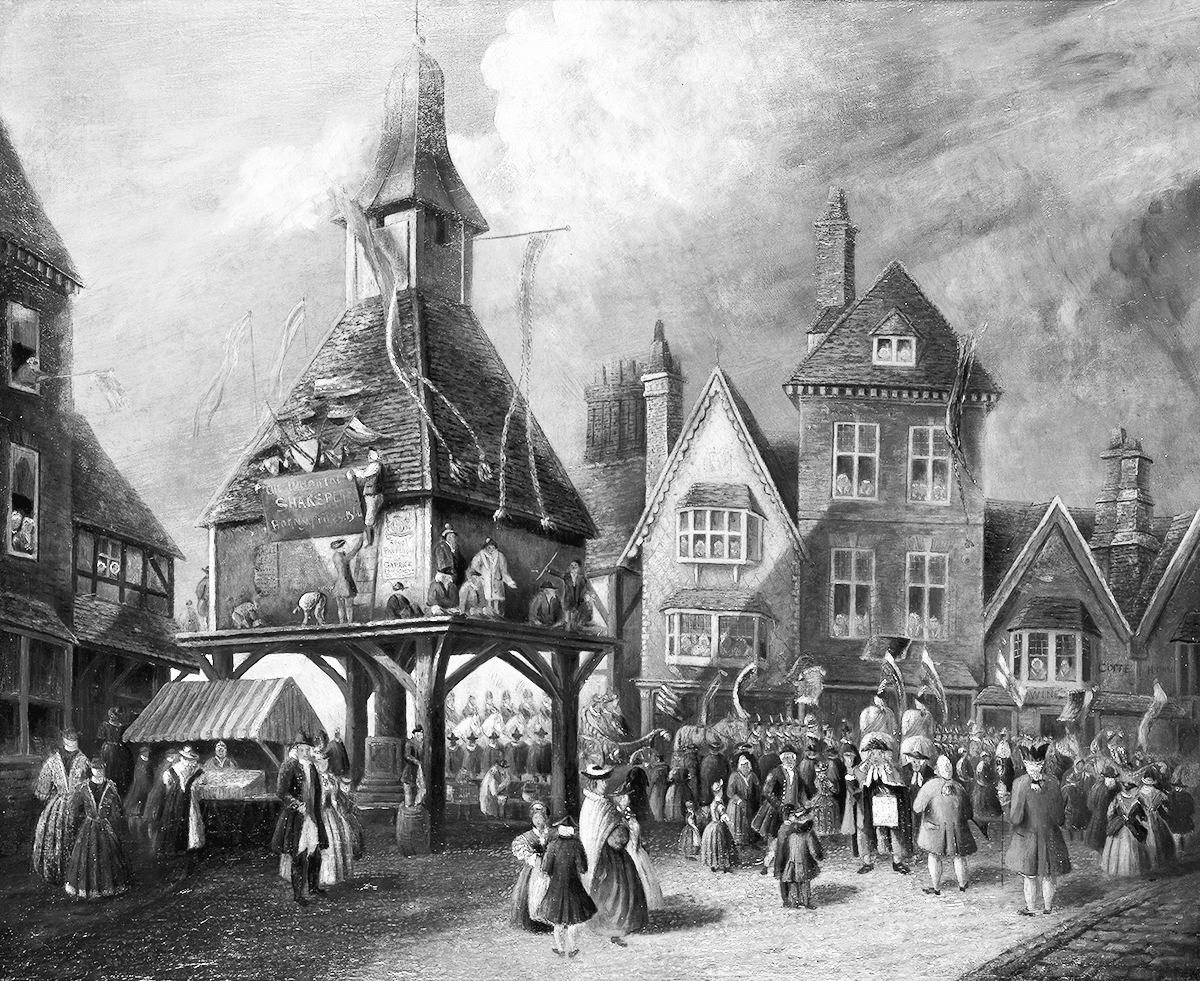

Stratford-upon-Avon’s High Cross marketplace at the height of the Jubilee. © Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

George Garrick had successfully persuaded enough Stratford residents to light their windows with candles and, with the musicians balladeering and visitors wandering through the glow in their ribbons and favors, the town took on a special aspect that even Charles Dibdin could not fail to appreciate, despite the rain. “It was magic,” he said. “It was fairyland . . . the effect was electrical, irresistible; every soul present felt it, cherished it, delighted in it, and considered that moment as the most endearing to sensibility that could possibly be experienced; when [a person] has said all this and ten times more, he would have given a faint idea of the real impression.” “All is Joy and Festivity here,” agreed the St. James Chronicle, “and what with the Rattling of Coaches, the Blazing and Cracking of Fireworks, the Number of People going and coming from the Mask Warehouse, where they repair to provide themselves with Dresses, my Head is almost turned and I think I may venture to say I shall never see such another Scene in all my Life.” Still some locals disagreed. “Notwithstanding the prodigious benefit evidently accruing to the inhabitants of Stratford from the Jubilee,” reported Musidorus,

it is inconceivable to think how many well-meaning people of the place were in a continual alarm for the safety of the town, which they actually imagined would undergo some signal mark of the Divine displeasure, for being the scene of so very prance a festival. In this opinion they were doubly confirmed . . . when the Town was illuminated for the Assembly, and some transparencies hung out at the window, for the amusement of the populace. . . . These devices struck a deep apprehension on the minds of the ignorantly religious; they looked upon them as peculiarly entitled to the vengeance of Providence, and wished the Londoners heartily at home, though they found our money so highly worth their acceptance.

The ball commenced at ten, with minuets danced until midnight. Refreshments were served and followed by country dances until three in the morning. Boswell, so tired he could hardly stand, made an appearance just long enough to ensure he had been seen. Still rattled from the threat to his chastity, to his great relief he went home alone, where his landlady, “a good, motherly woman,” came to him with a bowl of warm, sweetened wine called negus. It was terribly comforting. “I told her that perhaps I might retire from the world and just come and live in my room at Stratford.”