After such a late night, the next morning’s cannon blasts were met with less enthusiasm, as were the trilling of the fife and thumping of the drums. The ladies were again serenaded, but not so many roused themselves from their beds. One grand dame, peering out at the drab sky and immiserating rain, proclaimed, “What an absurd climate!” before retiring again. “It appeared,” remembered Henry Angelo, “as if the clouds, in an ill humour with these magnificent doings, had sucked up a super-abundance of water, to shower down upon the finery of the mimic host, and that the river gods had opened all the sluices of the Avon, to drown the devotees of her boasted bard.”

Rain threatened the ruination of the Jubilee, although anyone who cared to consult an almanac would have known that September was not ideal for outside pursuits in the weeping climate of England. The past two Septembers had been a washout. “Cloudy, churlish morning” and “smart rain from 6 to 3,” read the weather reports, “flying clouds, misty afternoon.” It had, however, been a remarkable year for farmers, “the greatest Plenty of Apples,” wrote the St. James Chronicle, “and other Fruit, ever known in the Memory of Man.” Water formed bronze pools in the muddy streets while the fringes of the Bankcroft meadow, on which the Rotunda stood, were seeped in rising river water. “What do you make of that?” Garrick asked Samuel Foote, pointing to a violently running drain. “I think,” said Foote, “’tis God’s revenge against Vanity!”

The first event planned for the day was a pageant of Shakespearean characters that was to process through the town from George Garrick’s base at the College before filing into the Rotunda, where they would line up in anticipation of the Dedication Ode. One hundred and seventy actors and local volunteers assembled to dress as directed, milling about in costume as their voices bounced off the high ceilings or they ran outside to shoo the children away from the puddles. Among them was the young Henry Angelo, representing the spirit Ariel, and Francis Wheler, the lawyer who had presented Garrick with the mulberry box, excited to be a part of the procession despite suffering an attack of hemorrhoids that had almost prevented him from reaching Stratford at all.

George called everyone outside and hurried about marshaling the group, placing them in the order his brother had ordained. At their head was a large triumphal car carrying actors representing the muses of Comedy and Tragedy—in essence, a cart that had been clad in pasteboard and decorated to befit the occasion, pulled along by six hairy-legged satyrs. Dancers dressed as the remaining seven muses and women playing tambourines and representing the three Graces were to skip alongside. Only nineteen of Shakespeare’s thirty-seven plays were included, those plays most commonly performed in Garrick’s theatre, with As You Like It taking the front and Antony and Cleopatra bringing up the rear. Each play was represented by a group of four or five processioners who bore a banner before them while performing in dumb show a scene that presented, in Garrick’s words, “some capital part of it in Action.” The result was a line of people who together formed the most memorable highlights of Shakespeare’s canon as understood by eighteenth-century audiences—Lear in the throes of madness, Macbeth holding a bloody dagger, Malvolio waving a forged love note, and Fluellen forcing Pistol to eat a leek.

As always, getting organized took time, and the props and costumes, creations of wire and tinsel that looked fabulous under Drury Lane candlelight, began to blister and crease in Stratford’s squalling rain. This horrified Garrick’s business partner James Lacy, who went immediately over to Garrick’s rooms to call the procession to a halt. Lacy had been opposed to the Jubilee from the start, condemning it as an “idle pageant,” and was adamant that the weather would ruin the silks and satins of his costumes and all the expensive properties that were needed for the upcoming season.

“See—who the devil, Davy, would venture upon the procession under such lowering aspects?” Lacy said. “Sir, all the ostrich feathers will be spoiled, and the property will be damnified five thousand pounds.”

Garrick had a strong aversion to Lacy and hated to be challenged by him. The two men quarreled often, with Garrick calling Lacy “the deepest of all politicians” and accusing him of constantly seeking to undermine his authority through “spies, deep researches, and anonymous letters.” Furthermore, Garrick complained, “There is a rank viciousness in his Disposition that can only be kept under by ye Whip & curb,” aggrieved that Lacy was sticking his nose in artistic decisions, a domain Garrick believed to be solely his, by hiring actors and superintending the rehearsals while being “insensible of my Merit and Services”—that is, being insufficiently grateful for the vast profits Garrick brought to the house through his acting and the plays and pantomimes he wrote at no additional fee. Even worse, Lacy mistreated George. “I am quite Sick of his Conduct towards Every body that love Me,” said Garrick. “He will never forgive my being the means of his making a figure in the world.”

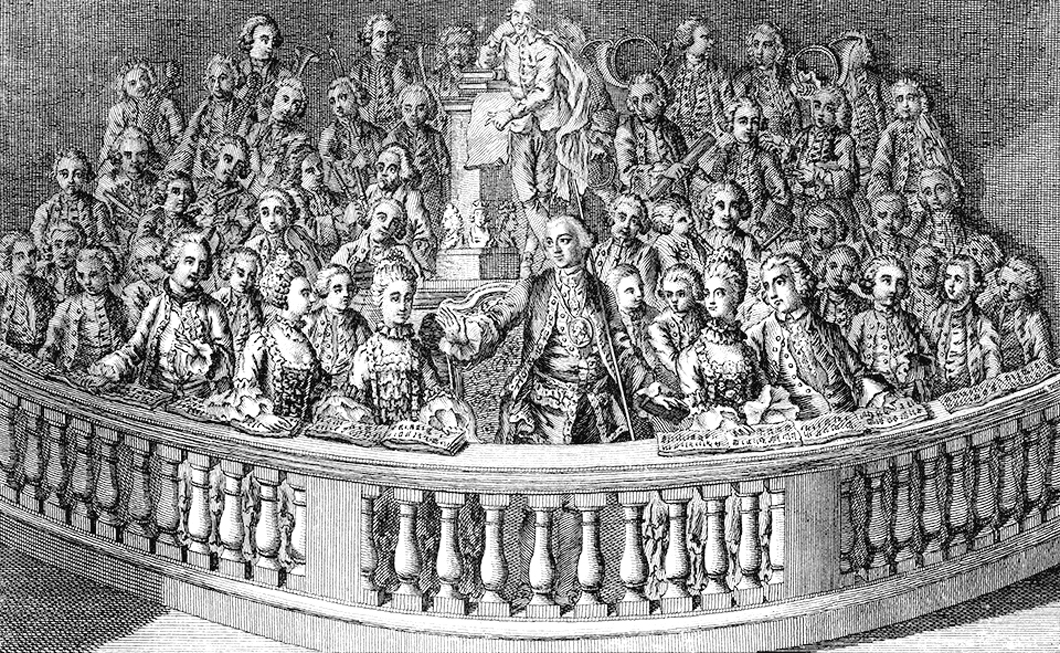

Announced in the bills as “A PAGEANT of the principal Characters in the inimitable Plays wrote by the Immortal Shakespeare,” these promotional images were produced before the parade was cancelled by James Lacy. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library

But the rain persisted and Lacy prevailed. Word was sent to the College for the performers to disperse and handbills were printed to announce the change:

To the

Ladies and Gentlemen

at the

Jubilee

Thursday Sep. 7th 1769

As the weather proves so unfavourable for the

PAGEANT

The Steward begs leave to inform them that it is

oblig’d to be deferr’d.

THE ODE

will be peform’d at 12 in the Amphitheatre,

The Doors to be open’d at 11

Garrick was humiliated. When Lacy left, he sat down to be shaved, only for the barber (who had been up late and was not yet sober) to cut him “from the corner of his mouth to his chin.” Eva applied styptics to stop the bleeding, but the wound was such that it delayed his getting dressed. The absence of the pageant placed even more pressure on the ode to be successful, the fundamental statement and cultural keynote of the occasion. Having controlled the bleeding, and now dressed in a freshly tailored suit of deep brown cloth embroidered with gold lace and a lining of ivory taffeta finished with thirteen gold buttons, Garrick reached for a slim packet of waxed paper that contained a pair of ivory-white gloves. These had been presented to him at the end of May by an old actor named John Ward, who had himself received them twenty-three years earlier following a performance of Othello he had put up to raise money to restore the Shakespeare memorial in Holy Trinity Church. The man who gave the gloves to Ward was a Stratford glazier named William Shakespeare, yet another person claiming descent. “These are the only property that remains of our famous relation,” he had said.

Irritated and anxious, Garrick straightened his coat, examined his wound, and stepped out in time for breakfast at the Town Hall at nine. The wind was blowing and the rain came down hard. He ate a meal that ended shortly before eleven and made his way over to the Rotunda. The river, which had been rising steadily for the past two days, sloshed at its banks and seeped deeper into the meadow’s long grass.

Close to a thousand people awaited him inside the amphitheatre. The space was beautiful in spite of the torrent outside, hung with crimson curtains and lit with eight hundred lights, which reflected off the gilding on the cornices and pilasters. Some slight adjustments had to be made now that Garrick wouldn’t be entering at the head of the pageant, so instead he made his way alone to the front of the rostrum that enclosed the orchestra in a crescent of balusters and sat looking over the audience as they continued to settle in. Behind him sat the entire orchestra and chorus of Drury Lane, more than one hundred performers, banked in a semicircle. Thomas Arne, dressed also in a brown velvet suit, stood to one side, while in pride of place at the orchestra’s highest point, stood John Cheere’s statue of Shakespeare, commissioned for the Town Hall’s empty nook.

Garrick looked nervous as the overture began, some even said “confused or intimidated.” He stood, and giving a respectful bow that was received with warm applause, began. “To what blest genius of the isle,” he asked his audience, “Shall Gratitude her tribute pay,” before presenting them with a verbal image of Shakespeare—“that demi-god”—attended by fey spirits and literary godkins:

Who Avon’s flow’ry margin trod,

While sportive Fancy round him flew,

Where Nature led him by the hand,

Instructed him in all she knew,

And gave him absolute command!

’Tis he! ’Tis he!

“The god of our idolatry!”

This last line, paraphrasing Juliet’s “swear by thy gracious self, / Which is the god of my idolatry” from Romeo and Juliet, was one that Garrick had been using for years, adopting it as a motto for his own Shakespeare mania. However, given the worship of the mulberry tree and the deep ritualistic reverence he was attempting to convey, opening the ode with such an admission made some listeners uncomfortable. “Pious ears were offended by the boldness of the expression,” remarked Lloyd’s Evening Post, “and others took occasion to compare the whole to the canonization of a Romish Saint.” Certainly, it was as if addressing a holy relic that Garrick turned at this point to the statue. “To him the song, the Edifice we raise,” he continued,

He merits all our wonder, all our praise!

Yet ere impatient joy break forth,

In sounds that lift the soul from earth;

And to our spell-bound minds impart

Some faint idea of his magic art;

Let awful silence still the air!

From the dark cloud, the hidden light

Bursts tenfold bright!

Prepare! prepare! prepare!

Now swell at once the choral song,

Roll the full tide of harmony along;

Let Rapture sweep the trembling strings,

And Fame expanding all her wings,

With all her trumpet-tongues proclaim,

The lov’d, rever’d, immortal name!

SHAKESPEARE! SHAKESPEARE! SHAKESPEARE!

Let th’inchanting sound,

From Avon’s shores rebound:

Thro’ the Air,

Let it bear,

The precious freight the envious nations round!

Although set to music, the ode was spoken, not sung. This was an innovation in itself, as audiences were used to hearing this kind of thing as operatic recitative. Garrick, however, thought that “the dullest part of Musick” and had decided to deploy instead his famous gift for oratory and expression. “It is an experiment,” he had told the Earl of Hardwicke, “but I think it worth ye Tryal.” It worked. Within the space of only a few stanzas, according to Benjamin Victor, it “had so great Effect, that, perhaps, in all the Characters he ever played, he never shewed more Powers, more Judgment, or ever made a stronger Impression on the Minds of his Auditors.” Garrick’s nerves began to fall away, and he felt himself approaching the height of his powers. “His eyes sparkled with joy,” wrote Boswell, who was thrilled to be part of such a defining moment of public spectacle, “and the triumph of his countenance at some parts of the ode, it’s tenderness at others, and inimitable sly humour at others, cannot be described.” His sentiment was not shared by the Warwickshire Journal, who felt that Garrick’s “Powers and Tone of Voice” were “much inferior to what they were in his meridian perfection,” while quoting a line from the Roman poet Horace, “Solve senescentem mature sanus equum,” which advises wise men to rid themselves of aging horses.

After each recited passage, Garrick sat down to make way for the chorus, who belted out a verse in support of the principal argument. “Swell the choral song,” they sang,

Roll the tide of harmony along,

Let Rapture sweep the strings,

Fame expand her wings,

With her trumpet-tongues proclaim,

The lov’d, rever’d, immortal name!

SHAKESPEARE! SHAKESPEARE! SHAKESPEARE!

Next Robert Baddeley rose, singing a song that described Shakespeare being garlanded by the muses (as depicted on the mulberry box that had initiated the entire Jubilee). Garrick then spoke again, declaring that Shakespeare’s achievement was superior to that of Alexander the Great, as while Alexander conquered earthly realms, Shakespeare could draw on the limitless resources of his “wonder-teeming” mind and raise “other worlds, and beings of his own!” By now, the audience was rapt, applauding every stanza and every song. After another song from Joseph Vernon, Garrick continued, paraphrasing the opening chorus of Henry V. “O from his muse of fire,” he said:

Could but one spark be caught,

That might the humble strains aspire

To tell the wonders he has wrought,

To tell, —how sitting on his magic throne,

Unaided and alone,

In dreadful state,

The subject passions round him wait;

Who tho’ unchain’d, and raging there,

He checks, inflames, or turns their mad career;

With that superior skill,

Which winds the fiery steed at will,

He gives the aweful word—

And they, all foaming, trembling, own him for their Lord.

With each passage, Garrick built on the image he presented of Shakespeare as the commander of the passions, a man who had not only understood the complexities of human nature but tamed them and bound them to his will. “Such is ye Power of Shakespeare,” Garrick had written, “that he can turn and wind the Passions as he pleases, and they are so Subjected to him, that tho raging about, and unchain’d they wait upon his Commands, and Obey them, when he gives ye Word.” This powerful ability to represent humanity, he argued, not only enriched the humanity of others, it forced them to confront themselves, even to the extent that the guilty would confess their crimes:

With these his slaves he can control,

Or charm the soul;

So realized are all his golden dreams,

Of terror, pity, love, and grief,

Tho’ conscious that the vision only seems,

The woe-struck mind finds no relief:

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Ye guilty, lawless tribe,

Escap’d from punishment, by art or bribe,

At Shakespeare’s bar appear!

No bribing, shuffling there—

His genius, like a rushing flood,

Cannot be withstood,

Out bursts the penitential tear!

The look appall’d, the crime reveals,

The marble-hearted monster feels,

Whose hand is stain’d with blood.

Just as Garrick was asking his audience to examine their consciences, an enormous crack was heard within the Rotunda, as an ill-timbered bench split under the weight of the audience and sent a row of people tumbling to the floor. At the same time, a gust of wind blew a door off its hinges—it fell on a number of guests, including Francis Wheler and the sixteen-year-old Lord Carlisle, who was knocked senseless and had to be carried outside by friends who feared for his life.

The audience reconstituted themselves as Samuel Champness sang before Garrick returned to compare Shakespeare to The Tempest’s Prospero, a “magician” and “Monarch of th’inchanted land.” Waves of repeating applause rang through the Rotunda as Eleanor Radley now stood to sing of Shakespeare as “the treasure of joy.” A young Drury Lane actress, fittingly known as a “songstress of nature,” Radley was a close friend of Sophia Baddeley, who gifted her her old clothes and jewels whenever she received a new set. The song marked a shift in gears as Garrick moved from considering Shakespeare’s tragic heroes to a long section reflecting on the genius of Falstaff, a “huge, misshapen heap” and “a comic world in ONE.”

Garrick delivers the Dedication Ode to a packed audience in the Rotunda, the statue of Shakespeare taking pride of place at the center of the orchestra. Used by permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library

Another song from Vernon, called “A World Where All Pleasures Abound,” “deserved the thunder of applause which was bestowed upon it” and set up a passage in which Garrick lamented the fact that the poets of Oxford and Cambridge universities had not taken up their pens in praise of Shakespeare’s genius, with the clear (and disingenuous) implication that it was a shame that a humble actor had been left to pick up the intellectual slack. This was followed by more of the now familiar mythologizing of the Warwickshire countryside, spiced with some local politics as the ode thanked the Duke of Dorset for permitting the removal of the willow trees to make way for the Rotunda, as well as his decision to forbid the surrounding fields from being enclosed for private farmland. These lines had clearly been inserted at the request of the Corporation of Stratford, “for which after the Performance,” Garrick told Hunt, “I expect yr thanks.” Robert Baddeley sang again before Garrick started to build toward the crescendo. “Can British gratitude delay,” he asked,

To him the glory of this isle,

To give the festive day

The song, the statue, and devoted pile?

To him the first of poets, best of men?

“We ne’er shall look upon his like again!”

This was the cue for the coronation and, as the music swelled, two actors moved toward the statue at the center of the orchestra to crown it with laurel garlands, singing,

Shall the hero laurels gain,

For ravag’d fields, and thousands slain?

And shall his brows no laurels bind,

Who charms to virtue humankind?

To which the entire Drury Lane chorus replied:

We will, —his brows with laurel bind,

Who charms to virtue human kind:

Raise the pile, the statue raise,

Sing immortal Shakespeare’s praise!

The song will cease, the stone decay,

But his Name,

And undiminish’d fame,

Shall never, never pass away.

As the final notes wavered and the spectators digested all they had seen, Lord Grosvenor rushed to the front, visibly trembling with emotion to tell “Mr. Garrick that he had affected his whole frame, shewing him his veins and nerves still quivering with agitation.” Wrote a correspondent for Lloyd’s Evening Post, “When I saw the Statue of Shakespeare, the greatest dramatic Poet, and the living person of Garrick, the greatest Actor that England ever produced; when I considered the Occasion, the Scene, and the Company which was drawn together by the Power of one Man, I was struck with a kind of Veneration and Enthusiasm.”

Boswell was equally in raptures. A lover of solemn ritual and believer in the power of communal artistic experiences to civilize society, he was the ode’s ideal auditor. Describing it as “noble,” he felt as if he had been exposed to genius, likening it to a performance one might have seen in ancient Athens or Rome. “The whole audience were fixed in the most earnest attention,” he wrote,

and I do believe, that if any one had attempted to disturb the performance, he would have been in danger of his life. Garrick, in the front of the orchestra, filled with the first musicians of the nation, with Dr. Arne at their head, and inspired with an aweful elevation of soul, while he looked from time to time at the venerable statue of Shakespeare, appeared more than himself. While he repeated the ode, and saw the various passions and feelings which it contains fully transfused into all around him, he seemed in extacy, and gave us the idea of a mortal transformed into a demi-god, as we read in the Pagan mythology.

But what exactly was this thing, half sung, half spoken, filled with florid pieties and verbal curlicues yet able to move grown men to tears? Formally, it was a Pindaric ode in varying meters, with eight passages of recitative, seven songs, and two full choruses. Like Garrick’s other Jubilee texts, it referenced Shakespeare’s work only obliquely, through allusions and half quotations, supplementing those with echoes of other literary authorities, including John Milton and John Dryden, whose own ode “Alexander’s Feast” was a clear influence. Above all, it was an actor’s poem, a patchwork incantation pieced together from a commonplace book of half-remembered lines and bits of oratory that together conspired to sound important. Gauzy and indirect, it implied the presence of Shakespeare’s spirit without tackling the facts of his textual body and, as such, was a verbal companion to the abandoned pageant, inasmuch as it aimed to distill the substance of Shakespeare into a synoptic form. It was the theatrical adaptation par excellence, an apotheosis, the grand summation of a century of playing and thinking about Shakespeare that stripped him of the compromising realities of his work and set him on a marble-smooth throne of genius. Shakespeare had ascended, and it was not necessary to read a single page of his work to know this to be true.

Garrick was not only delighted by the ode’s reception, he was enormously relieved. He had been anxious as to whether his skills as an author were equal to the occasion, consulting with Thomas Warton, the Oxford professor of poetry, throughout its composition. “I must say that his ode greatly exceeded my expectations,” wrote Boswell, addressing now the quality of the poetry in the performance he had just witnessed, “I knew his talents for little sportive sallies, but I feared that a dedication ode for Shakespeare was above his powers.” Boswell was no doubt thinking of Samuel Johnson’s words, who had told him that “Little Davy is a very good actor but as to poetry, he never wrote but one line in his life.” Boswell continued, “What the critics may say of this performance I know not, but I shall never be induced to waver in my opinion of it. I am sensible of it’s defects; but, upon the whole, I think it a work of considerable merit, well suited to the occasion, by the variety of it’s subjects, and containing both poetical force and elegance.”

Critical opinion, in fact, reached a rather swift consensus as to the merits of the ode. “Impartiality,” wrote a correspondent for the Warwickshire Journal, “obliges me to say, that the Ode in itself will not bear reading to Advantage. . . . His images want magnitude for such an object, nor does he always apply them with propriety.” Horace Walpole, Garrick’s neighbor, who was then in Paris, was blunter. “I have blushed when the papers came over crammed . . . with Garrick’s insufferable nonsense about Shakespeare,” he wrote to a friend. “As that man’s writings will be preserved by his name, who will believe that he was a tolerable actor?” Back in the audience, meanwhile, the embittered Charles Macklin plotted a more public rebuke, scribbling notes that quibbled with every line. Outraged that Garrick should have the temerity to invite esteem as a poet, Macklin compiled his thoughts into a pedantic letter that accused the ode of imprecise language and botched imagery, deploying scoffing complaints such as saying that while he had heard of raising cabbages, it was preposterous to claim that Shakespeare had “rais’d other worlds.”

Garrick penned a long and patient reply, scrawling on the envelope of his copy, “I might have spent my time better than supporting a foolish business against a very foolish man.” Macklin’s quibbles reappeared, with further elaborations, in a series of four articles published six weeks after the Jubilee under the pen name “Longinus,” in reference to the first-century author of an aesthetic treatise that focused on good and bad effects in writing. That the objections are almost identical suggests that Macklin and Longinus were one and the same. “My indignation is at length raised to such a pitch, at the highest insult I have ever known offered to the public taste, that I can contain it no longer,” he wrote, before taking the reader through ten dyseptic and closely argued pages that condemned the ode for containing “almost every thing that is false in writing,” and being “defective in the small articles of genius, taste, sentiment, language, composition, numbers, (except in the many stolen lines) rhime, grammar, common sense, and common English.” It had taken many years, but Macklin had his revenge.

Whatever Garrick’s enemies had to say, the general view was that the sense of occasion spared the ode and rendered it “superior to Criticism.” This was, after all, a performance, and not merely a man reading his work aloud. The London Museum wrote that, while the ode was “not only without sense or poetry, but full of the most displeasing and inapplicable images,” Garrick “robs nonsense of its dullness, and impropriety of its defects, merely to convince us of a feature in his character we were not before acquainted with, that whatever he repeats, requires no collateral assistance.” Garrick’s great skill, it argued, was in “making nonsense agreeable.”

After the lengthy applause had died away, a reflective hush fell about the Rotunda. Garrick then thanked Arne and the musicians, apologized for his deficiencies as poet and orator, and told the audience that if they still required a greater authority for the merits of Shakespeare, they should consult their own hearts. “I would not pay them so ill a compliment as to suppose, that he has not made a dear, valuable, and lasting impression upon them!” he said. “Your attendance here upon this occasion is a proof that you felt—powerfully felt his Genius, and that you love and revere him and his memory.” Like a preacher asking his congregation to offer testimonials of divine grace, Garrick looked across the many seated faces. “That only remaining honour to him now (and it is the greatest honour you can do him),” he said, “is to speak for him.” There was a pause and some embarrassed laughter among the crowd. Garrick continued: “Perhaps my proposition comes a little too abruptly upon you?” he said, and gesturing toward the orchestra, continued, “With your permission, we will desire these gentlemen to give you time, by a piece of music, to recollect and adjust your thoughts.”

As the music played, Garrick asked the crowd again: “Now, Ladies and Gentlemen, will you be pleased to say any thing for or against Shakespeare?” There was a small disturbance, at which point a man stood up and, taking off his great coat to reveal a blue suit embroidered with silver frogs (an audaciously Parisian style), he approached the orchestra and began to complain that Shakespeare was an ill-bred, vulgar author, who excited braying laughter and unseemly tears, “when it was the criterion of a gentleman,” he insisted, “to be moved at nothing—to feel nothing—to admire nothing!” This statement was merely a prologue to a fuller harangue, in which the man in the blue frog suit accused Shakespeare of being a debaucher of minds, when, he said, “the chief excellence of man, and the most refined sensation was to be devoured by ennui, and only live in a state of insensible vegetation!” The audience grew restless as he rambled on, slandering Garrick, the Corporation of Stratford, and the entire Jubilee, until eventually it began to dawn on many that the heckler was none other than Tom King, the Drury Lane comedian and one of Garrick’s most reliable performers. King was parodying Voltaire, playing devil’s advocate to such an absurd degree that any lingering opposition to Shakespeare’s claim as the greatest writer of all time would be shamed out of existence.

But the anti-masque fell flat, as King was too well-known to be taken seriously and there was no one in the audience who even remotely sympathized with Voltaire. “This Exhibition looked so like a Trap laid on Purpose, that it displeased me,” wrote Boswell, who feared the incident lowered the tone. Lloyd’s Evening Post also found it insipid, “and I could wish that that part of the entertainment had been left alone.” King returned to his seat, and Garrick delivered an epilogue addressed to the ladies of the Jubilee, thanking them specifically for the good sense and patriotism their sex had shown by sponsoring Shakespeare’s initial return to the stage in the 1730s through the auspices of the Shakespeare Ladies Club, and for helping to fund his monument in Westminster Abbey. And with that, the coronation of Shakespeare as the genius of Britain was complete.

The audience began to leave, no doubt confident that they had witnessed an event that had tilted irrevocably the axis of culture. Charles Dibdin was not so sure. “If GARRICK felt all this extacy, and imparted it to his auditors,” he wrote,

and fraught with nothing more than a noble ardour to lend tribute towards immortalizing his glorious bard, I know that it was called forth by a contemplation of the prodigious remuneration that would result to himself. It was acting; and, while he was infusing into the very souls of his hearers the merits of the incomparable SHAKESPEAR, the author of his own transcendent fame, and GARRICK’S ample fortune, his soul was fixed upon DRURY-LANE treasury.

Outside the Rotunda, the rain continued to fall, its fresh chill now mixed with the beefy aroma of roasting turtle.