Damp guests tried their hardest to amuse themselves until the dinner at four o’clock prepared by Mr. Gill, a cook of Bath, who had come to assist his brother, a drunk of Stratford, along with half a dozen other local cooks. The menu was venison and turtle, the latter an exotic, festive dish, offered on special occasions only. Edmund Burke had treated Garrick to one in 1768, writing to him that it was “an entertainment at least as good for the palate, as the other for the nose. Your true epicureans are of opinion, you know, that it contains in itself all kinds of flesh, fish, and fowl. It is therefore a dish fit for one who can represent all the solidity of flesh, the volatility of fowl, and the oddity of fish.” Certainly it presented the diner with options. Three separate dishes could be made from a single animal. Once the head and fins were removed and the guts and belly meat (known as the collops) had been cut from the shell, the collops were stewed with sweet herbs and Madeira and served like veal cutlets, the fins descaled and baked, while the guts were stewed with quince butter and served up in the shell. The taste was reminiscent of neck of beef.

Boswell forwent the chance to feast on turtle, dining alone with the bookseller Richard Baldwin. Baldwin was a literary businessman with shares in a number of newspapers, including the Public Advertiser, and spoke enthusiastically of growing its circulation and boosting its value to £2000 a year. Boswell himself was looking to buy shares in The London Magazine, a monthly to which he made regular contributions. They ate and discussed business, before Boswell excused himself and returned to the matronly Mrs. Harris’s to prepare for the evening’s masked ball.

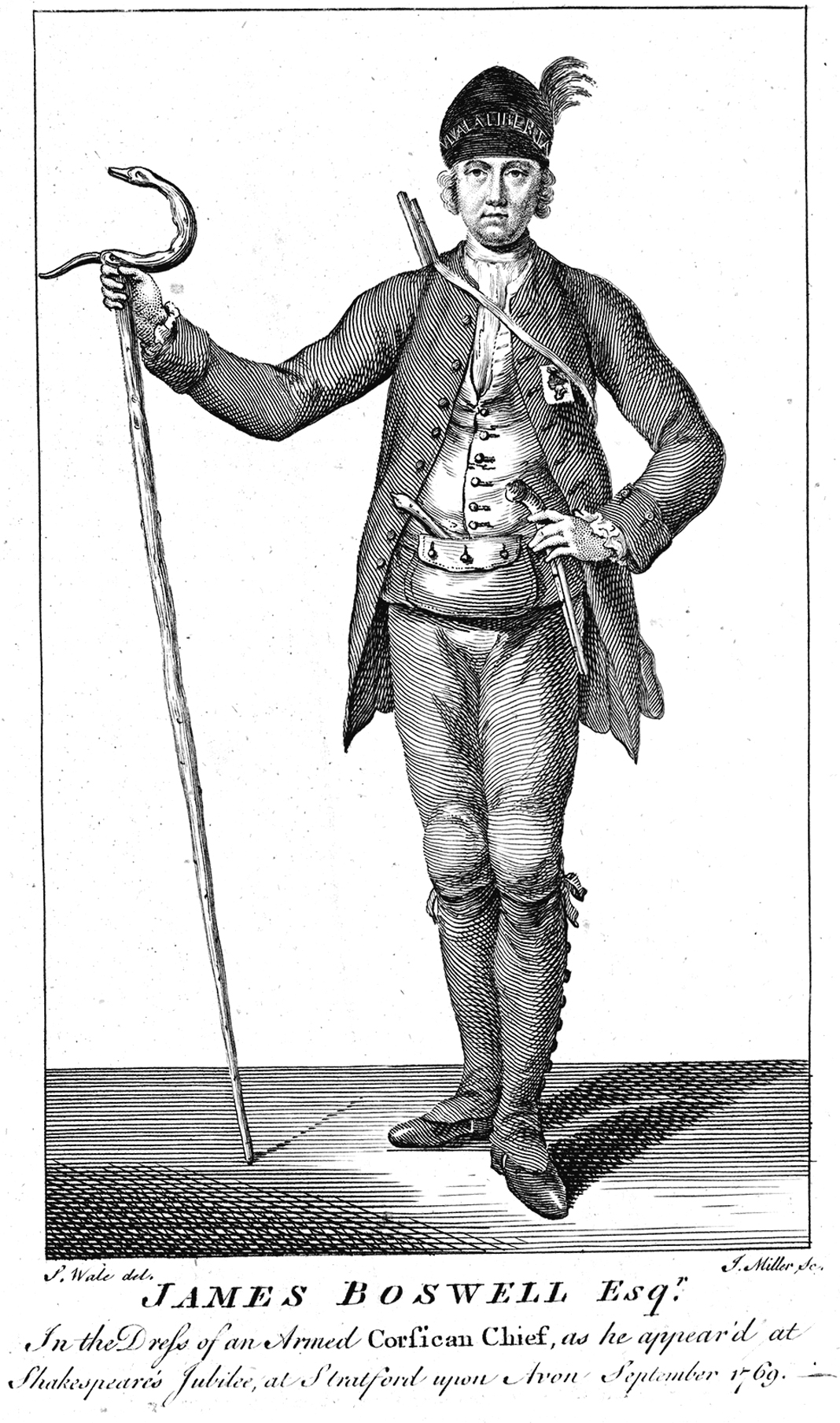

The ball was yet another component of the Jubilee that had nothing to do with Shakespeare, “well enough calculated for vacant minds,” wrote George Steevens, Garrick’s enemy, in Lloyd’s Evening Post, “to gratify ostentatious pride juvenile vanity, and luxurious opulence; and, in short, such as policy directed, in compliance with the vitiated taste of these times.” It was also a prime opportunity for Boswell to excel in the business of promoting his person, enlarging his notoriety as a writer among the cream of society and making the world more broadly aware of An Account of Corsica. This he would do by attending the ball dressed as a Corsican freedom fighter, although his last-minute decision to attend the Jubilee meant that he had left his authentic Corsican attire in Edinburgh. The costume he brought had been patched together in London and took the form of a scarlet waistcoat and breeches worn beneath a coarse coat of dark cloth, onto which he had sewn the Moor’s head crest of Corsica. A tall mitred hat had been commissioned in haste from Mr. Dalemaine, the Covent Garden tailor, and embroidered with the words “Viva la Libertà” in gold letters and decorated with a blue feather and cockade, “so that it had an elegant, as well as a war-like appearance.” Black splatterdashes, a kind of legging, were laced up to his knees. Around his waist, he tied a cartridge pouch, into which he shoved a pistol and stiletto, while a musket was slung across his shoulder. He wore no wig, but rather had his hair plaited into a single strand tied with a blue ribbon. In his hand, he carried the bird-headed staff he had come across in Cheapside. Admiring his reflection, he felt certain that dashing figure would reflect just as well on his fiancée as it did on himself. “When I looked at myself in the glass last night in my Corsican dress,” he told Margaret,

I have that kind of weakness that, I could not help thinking your opinion of yourself might be still more raised: “She has secured the constant affection and admiration of so fine a fellow.” Do you know, I cannot think there is any harm in such a kind of weakness or vanity, when a man is sensible of it and it has no great effect upon him. It enlivens me and increases my good humour.

So satisfied was Boswell feeling that he broke his promise to his friend Dempster that he would not write anything about himself at the Jubilee for the papers. Not only was he mentally composing the paragraph he would place in The London Magazine even as he dressed, he subsequently sat down and wrote some verses to commemorate his visit, sending them out to a printer who had advertised the bold claim that during the Jubilee all printing jobs could be turned around in an hour. Boswell hoped to hand these out as he entered the ball, a live prosodic commentary on the moment, but the printer, distracted by the promise of a fireworks display, had deserted his station. Instead, Boswell sent to the regular printer and found there an adept Scots boy who promised to bring him proofs as soon as they were done.

The distracting fireworks were being prepared by Domenico Angelo, hard at work behind his ornamental screen on the far side of the river in the hopes of delivering a display grand enough to mark the end of this special day. It would begin with another transparency lit by hundreds of colored lamps; this one showed Time leading Shakespeare to immortality, flanked on one side by Tragedy and by Comedy on the other—an idea, which while copied again from Sir Joshua Reynolds, was a perfect illustration of the logic of the ode. The fireworks that followed had been planned in three parts. The first began with a large line of rockets, each discharging three times, followed by twelve half-pound sky rockets and four “tourbillons,” fireworks that rose and spun like a whirlwind. Next came four balloons, two vertical wheels, two cascades with loud reports, and one fire tree in “Chinese fire.” The final section comprised two large pieces that underwent three transformations, from sun to porcupine quills and eight-pointed stars, two “pigeon wheels” with seven pigeons each, and two horizontal tables with six vertical wheels and illuminated globes. The bridge across the Avon had been rigged so that blazing serpents would appear along its span.

Unfortunately, for all the care Angelo had given his spectacle, he couldn’t control the rain or stop the dark night from growing increasingly chill. Everything was so permeated with damp that not even the first round of fireworks would go off. “The rockets would not ascend for fear of catching cold,” recalled his son, Henry, “and the surly crackers went out at a single pop.” Meanwhile, the Avon continued to rise, submerging the meadow in inches of water. Of the many eyeing the rain with trepidation, only Hugo Meynell, the MP for Lymington, was wise enough to evacuate, arranging a relay of horses he offered to anyone who wished to leave before it was too late.

Having called off the pageant, Garrick refused to concede the ball, which he insisted would begin at eleven as advertised. The first to arrive was the industrialist Matthew Boulton, dressed in the character of a Turk wearing an outsized turban decorated with artificial jewels made by workers at his factory. He stood alone for a while, as it was another hour before the larger body of people began to drift in. This became a steady stream by midnight, among them Garrick, who came dressed only in the suit that had become his unofficial steward’s uniform, lest the partygoers expect him to spend the whole night playing a role. He opened the ball with an oration on the qualities of Shakespeare that amounted to a summary of eighteenth-century literary theory. After a long day of speeches, it required every fiber of goodwill on the part of his audience to struggle through.

Soon enough, the ball was “packed to extravagance,” with various estimates placing the number of guests between one and two thousand. Many of them were notable members of society, including three ladies dressed as the weird sisters from Macbeth who also happened to be three of the reigning beauties of the day—Lady Pembroke, Harriet Bouverie (wife of the MP for Salisbury), and Mrs. Crewe. “The astonishing contrast between the deformity of the feigned and the beauty of the real appeared was every where observed,” remarked one paper. Beyond the Jubilee, Pembroke, Bouverie, and Crewe were also known as members of the “anti-patriotic Coterie” for their loyalty to the king and fierce opposition to John Wilkes.

The theatrical couple Mr. and Mrs. Yates came as a French fop and a wagoner respectively. Lord Grosvenor, who had the same idea as Matthew Boulton and came dressed as an eastern plenipotentiary with a large turban and white feather, began immediately to tuck into a plate of ham. The daughters of Sir Robert Ladbroke, the former mayor of London, came as a shepherdess and Dame Quickly from The Merry Wives of Windsor, respectively, while other costumes included a gentleman dressed as Lord Ogleby from The Clandestine Marriage (a play by Garrick and George Colman), a jockey, a man dressed to perform the “Dutch skipper” (a country dance), a trio of female Quakers, a Wilksite patriot, a druid, several milkmaids, a Chinese mandarin, two highlanders, Merlin, a fat Spanish courier, and a man wearing only his regular clothes and a pair of cuckold’s horns. Also spotted in multiples were assorted sailors, Oxford dons in scholarly gowns, conjurers, farmers, and harlequins. Many costumes consisted of mismatched garments or were simply confused. Others put in no effort at all, the men either wearing dominos—the large, checkered, sacklike gowns traditionally worn at Venetian masquerades—or coming entirely unmasked. The problem was not demand but supply; the shocking profiteering in fancy dress was exposed by Town and Country Magazine, which revealed that “Dresses of the meanest sort were hired at four guineas each, and the person who carried them down from London made above four hundred on the occasion; those, however, who could not be accommodated to their minds or did not chuse to pay such a sum, were admitted with masques only, and there were many present even without masks.” A rumor circulated that Samuel Foote was going to appear dressed as the Devil upon Two Sticks, the central character from one of his most successful productions, but Foote had already vacated Stratford in order to work on his Jubilee satire, complaining as he went that he had spent six guineas for nine hours’ sleep. As always, a strand of erotic play ran through the night as classical goddesses passed through the crowd handing out favors: “An ear of wheat from a sweet Ceres, and a honey suckle from a beautiful Flora,” wrote the correspondent from The Gentleman’s Magazine, who “kissed each of their hands in testimony of my devotion.”

As the Rotunda filled, a crowd of curious people hung by the entrance enjoying the costumes and hoping to peer in. Others sought entry despite arriving ticketless. One man from London, “made pot valiant with liquor,” tried to push his way in, shouting, “Do you know who I am?” but failed in his attempt. Inside, the overall impression was that the event was not going very well. “So completely was the ‘wet blanket’ spread over the masqueraders,” wrote Henry Angelo, “that each, taking off the mask, appeared in true English character, verily grumblers.” Nocturnal rheum had dulled the edge of wit. “It was remarked,” wrote a correspondent for The British Chronicle, “that though so many of the Belle Espirits were present, very few attempts at wit were made during the evening, nor did our Correspondent recollect a single Bon Mot that was worth transmitting to us.” One attempt at a joke was recorded on behalf of Cook, a clergyman of Powick in Worcestershire who had come dressed as a chimney sweep. Crying “Soot O! Soot O!” he was accosted by Lady Craven (then only nineteen years old but destined for a glamorous life as the Margravine of Anspach), who asked “Well, Mr. Sweep, why do you not come and sweep my chimney?” “Why, an’ please your Ladyship,” replied the Reverend Cook, “the last time I swept it, I burnt my Brush.” Cook later found himself in an argument with a man dressed as a devil who had been making impertinent remarks to the ladies. The reverend struck him with his brush. The devil retaliated by punching Cook in the face.

When Boswell entered, he came unmasked to represent, he said, “that the enemies to tyranny and oppression should wear no disguise.” (It also helped, of course, to let people see who he was.) According to the anonymous account he would send to The London Magazine, he made quite the impression, writing that “one of the most remarkable masks upon this occasion was James Boswell Esq.” He chatted first with Eva Garrick and then Lord Grosvenor, the two of them discussing the relative merits of the countries they represented “so opposite to each other—despotism and liberty,” before reacquainting himself with the lovely Mrs. Sheldon and asking her to dance, confident that his pistols and dagger (items he prophylactically referred to as “armour”) protected him. By this time, the swelling river that had previously confined itself to the meadow had begun to seep into the Rotunda, creeping across the dance floor and splashing over Boswell’s shoes and splatterdashes as he danced. As the minuets concluded, the eight hundred guests who had purchased additional tickets sat down to an ingenious supper, served in ambigu in which “not one thing appeared as it really was.” Once the tables were cleared, country dances began. At this point, William Kenrick, who had been waiting all night to make his entrance as the ghost of Shakespeare, came in so wet and frozen that it rendered superfluous his white makeup. He already looked like he’d died of exposure.

James Boswell in his masquerade dress. Though hastily put together in London, it was striking enough to warrant a “fine Whole Length” in the September 1769 issue of The London Magazine. © The Trustees of the British Museum

At two o’clock in the morning the small Scots boy Boswell had entrusted with his verses arrived with a single proof copy. Instead of distributing copies of this treasure as originally planned, Boswell decided to recite it. Trying but failing to capture the attention of all those within earshot, he managed at least to collar Garrick, who stood patiently by as Boswell began to rhapsodize in the voice of a Corsican patriot driven from his home to soothe his soul “on Avon’s sacred stream.” Addressing Shakespeare’s global relevance, and lamenting that the bard was not alive to dramatize the Corsican struggles, he turned to heralding Garrick as Shakespeare’s heir “who Dame Nature’s pencil stole, / Just where Old Shakespeare drop it.” Boswell’s Corsican came, he insisted, not to pity his country for their want of a Shakespeare or a Garrick but merely to ask that a portion of the enthusiasm on display might used to liberate his own island. “Let me plead for Liberty distrest,” he read:

And warm for her each sympathetick breast:

Amidst the splendid honours which you bear,

To save a sister island! be your care:

With generous ardour make us also free,

And give to CORSICA, a noble JUBILEE!

It was not a terrible effort given the time constraints, a thoroughly Boswellian ode, professing a Boswellian logic that united Shakespeare, Garrick, and Corsica and placed Boswell at the center of it all. And why not? This was exactly the kind of improvised meaning-making that the open structure of the Jubilee, with its muddled iconography and layered non sequiturs, encouraged. Garrick, listening patiently, noticed that the water was spilling into his shoes.

At five in the morning, with the water now up to the shins, a general call went up to abandon the Rotunda before the entire building floated away. “No delay could be admitted,” wrote Joseph Cradock. Planks were laid across the meadow and used as ramps up to the steps of the carriages, the wheels of which were sunk as much as two feet deep in waterlogged grass. Men volunteered to carry women on their backs, including the impudent devil who gallantly took up a young woman only for a gust of wind to reveal a pair of leather breeches hidden beneath her skirts, at which point this man in drag was dumped unceremoniously into the water. Treacherous hidden ditches concealed themselves beneath the surface, as was discovered by “A Young Gentleman of London,” according to Berrow’s Worcester Journal, who slipped into “a very deep mirey Dyke, but fortunately being within Reach of a Stump, supported himself by it, and called out for Help.” A rescuer went to his aid, “but in his hurry and eagerness likewise slipped in Lanthorn and all, and both of them must have been smother’d,” had not others pulled them out. As the evacuees splashed away, the Rotunda creaked and groaned, loosening its hinges as its foundations imperceptibly rose and began to float.

“We did not get home,” wrote Boswell, recalling that sodden evening, “till past six in the morning.” After three hours of shallow sleep, he rose and called again upon Richard Baldwin, with whom he ate breakfast. “The true nature of human life began now to appear,” he said. “After the joy of the Jubilee came the uneasy reflection that I was in a little village in wet weather and know not how to get away.”

Rain always depressed Boswell’s spirits, an affliction Samuel Johnson had mocked him for, but on reflection, he was happy with what he felt he had achieved. “I pleased myself with a variety of ideas with regard to the Jubilee, peculiar to my own mind,” he said. For him, the focus had not been on Shakespeare so much as the ways in which Shakespeare might be used as a means to draw together his own considerable talents for sociability, sensibility, sensuality, and self-promotion.

Like most in Stratford that Friday morning, Boswell’s first thought was to flee, but with the rain continuing to fall for a third consecutive day, the few coaches and sedan chairs that clogged the muddy streets were all spoken for “I don’t know how many times over, by different companies.” John Payton prepared the usual public breakfast at the Town Hall knowing, as the agent and dispatcher for nearly all of the public conveyances within a fifty-mile radius, that many of his guests would have to stay on at an additional guinea a night. “We were like a crowd in a theatre,” wrote Boswell. “It was impossible we could all go at a time.” Escape was futile—“Five, nay Fifty Guineas were unable to attain it.”

After several fruitless inquiries, Baldwin found Boswell a seat in a coach with an “honest Scott” that was due to leave the following morning. With nothing to do until that time, Boswell went to the White Lion and was introduced to two gentlemen from Lichfield who knew Johnson and Garrick and had heard of Boswell by repute—“It is fine to have such a character as I have,” he mused. “I enjoy it much.” After this, he went to Shakespeare’s tomb, observing with pleasure that Shakespeare’s wife, Anne Hathaway, had been older than him, just as Margaret was older than Boswell. While taking in the church, he began to have second thoughts about the carriage ride Baldwin had arranged for him, concerned that the “honest Scott” had a reputation for dissipation that might imperil the success he had had restraining himself so far. Instead, he sought out William Richardson and his friend Captain Johnston and persuaded them to give him a seat in their chaise.

With his money running low, Boswell next went to see Garrick and, presenting him with a packet of the previous night’s verses, asked for a loan of five guineas. Garrick moodily dismissed the request with the claim that George had taken all his money. Boswell persisted. “Come, come, that won’t do,” he said to Garrick with curt familiarity. “Five guineas I must have, and you must find them for me.” The exchange typified the way in which Boswell responded to Garrick’s fame now that he had a taste of his own. Where he had once been awestruck, he was now competitive and almost insolent, as if he felt it was necessary to take Garrick down a peg or two in order to assert his own identity, or be subsumed by his friend’s superior celebrity. But Garrick was exhausted and his mood was rapidly souring. With no patience to quarrel with Boswell, he called to Eva, who handed over her purse.

Garrick’s sincerest wish was that he could leave too. When news filtered through that the continued deluge meant that the pageant of characters had to be postponed again, and that the ruination of the Rotunda meant that it would be impossible to repeat the ode as had been requested, “the principal Part of the Company who had carriages of their own”—namely, aristocrats and wealthy businessmen—“went out of Town.” Other events went ahead as planned, including the horse race scheduled for Friday afternoon set on a beautiful meadow in Shottery less than two miles out of town, largely at the urging of Lord Grosvenor. The Jubilee Cup, as the race was called, had only five entrants, all running up to their knees in water. The winner was the colt Whirligig and his rider, Mr. Pratt, who was presented with a silver trophy engraved with Shakespeare’s arms and worth fifty pounds, before modestly declaring “his resolution never to part with it, though he honestly confessed—he knew very little about Plays, or Master SHAKESPEARE.”

Those who remained had to fend for themselves. Some braved the waterlogged ruins to be entertained with a performance of clarinets and French horns, and by nine o’clock that evening the skies had dried enough for Angelo to give a truncated firework display, before packing up and moving on to the Lichfield races, where he had been given an offer to perform his show the following day. At eleven, the Town Hall hosted a final assembly led by Mrs. Garrick, who danced minuets and country dances until four in the morning.

Boswell finally escaped at dawn, struggling through streets that looked as if had been turned over by an advancing army with a full baggage train, only for his coach to break down in Oxford, where he was once more disturbed with thoughts of the sirenian Miss Reynolds. It was a difficult journey home, but Boswell reflected on it with stoicism. “Taking the whole of this jubilee, said I, is like eating an artichoke entire. We have some fine mouthfuls, but also swallow the leaves and the hair, which are confoundedly difficult of digestion.” At least he made it home alive. Mr. James Henry Castle of St. Ives started sneezing and running a fever as a result of spending the night in damp sheets. He died, a martyr to the love of Shakespeare.