Benjamin Kosses, 1942

In the years before the war, I used to bike about nine miles to school every day with around thirty other children. There were three other Jewish children in the group and a few boys from NSB families. We ate our lunch at school. Our mothers used to wrap up our sandwiches in old newspapers. One day, one of the boys unwrapped his lunch from Volk en Vaderland, the NSB newspaper. He spread out the paper on the table and pointed at a cartoon of a rich Jew with a beard who was being deported. He looked at me and said, “That’s what they should do to all of the Jews.”

“If you start going on about Jews again,” I said, “I’m going to beat the living daylights out of you.” The others fired us up. I gave him a whack. He hit back. Then I picked up a meter ruler and I lashed out at him. He ducked, and it slipped out of my fingers and flew straight through an old map on the wall. Everyone fell silent. I walked right out of that room and headed for the house of Mr. Jonker, the school principal. He opened the door with a sour expression on his face. Jonker hated being disturbed at lunchtime. I told him what had happened. “Just go back to school,” he said. “I’ll be there soon.”

That afternoon at half past three, there was still no sign of the principal. I started biking home with the whole group. About halfway there, a bunch of boys, friends of the one I’d been fighting with, jumped out from behind some trees and pulled me off my bike. I dished out as many blows as I could, but there was no way I could take on eight of them. Finally we all landed in the ditch. The boys and girls I biked to school with every day didn’t lift a finger to help me, and they didn’t even say anything either. I arrived home, covered in bruises, dirty and soaking wet, to find a bicycle propped up outside the house. Mr. Jonker was inside, talking to my parents. He was very much against the NSB, but felt that it was better not to speak out about it at school.

When I left school in 1936, I went to work for my father at first. He was a cattle dealer and butcher. He worked mainly with sheep and calves, and he often used to bring large herds over from Germany, just across the border. We slaughtered the animals ritually and kept to the Jewish traditions. My father used to get home by four every Friday evening, before Shabbat began and the work would stop.

After six months, my father said, “You should spend some time with someone else as an apprentice and see how things are done elsewhere.” That’s how I ended up with an aunt and uncle in Nieuwe Pekela who also had a slaughterhouse. I worked there until shortly after the war broke out. Then the Germans seized their business. That meant: cows gone, money confiscated, end of the slaughterhouse. My father also lost his cows. So a Christian colleague of my uncle’s, Abraham Buzeman, offered me work. In 1941, it was still permitted for Jews to work with non-Jewish people.

When we were working in the slaughterhouse in Oude Pekela one day, a man called Koene came by. He was a butcher and he also belonged to an organization called Landwacht Nederland, which was a sort of special police force set up by the Germans and made up mainly of NSB members. With me standing right there, he said, “Bram, you need to get rid of that Jew assistant. He’ll ruin your business.”

“Koene, I’m the boss here, not you. Now clear off before I kick you out onto the street.”

Koene left, but he came back later, in a black uniform and with two friends. They stood in the doorway and one of the men said, “Bram, you heard what Koene told you: You have to stop letting that Jew boy work in the slaughterhouse. Get someone else to do the work.”

“I’ll decide that for myself,” said Buzeman.

There were six of us working that day, and there were three of them. But they were carrying shotguns. When one of them took his gun from his shoulder, we jumped on them and gave them hell. They stank of jenever.35 They’d obviously helped themselves to a little Dutch courage before they came to see us.

After that I didn’t go back to the slaughterhouse, but I continued to work for Buzeman at home, where we made sausages and other things. Koene must have heard about it, because he came to have another word with Buzeman. “Now you’ve got that Jew boy working at your own place. He’s got to go. If you don’t sort it out, I’ll make sure you’re carted off.”

After Koene had left, I said, “I’m going. I can’t stay here.”

“You don’t have to leave. I’ll never let them have their way.”

I left anyway. It was December 1941 and I went to work for a farmer in Nieuwe Pekela. They picked up Buzeman all the same and sent him to a concentration camp. He came back, but he caught a disease in the camp, which killed him soon after the war.

Six months later, my uncle came to see me. The local policeman had been to talk to him. “I’ve been told to arrest you and Bennie before Wednesday morning,” he had said, “and take you to Winschoten and hand you over to the Germans at the station. I’m not going to arrest you now, but if you’re at home on Wednesday morning and you haven’t taken the tram to Winschoten yourselves, I’ll have to take the two of you in.” We understood his warning.

“I’m not getting on that tram,” I told my uncle.

“Me neither,” he replied. “But where are you going to go?”

“I don’t know.”

“Let’s go together. It’ll be easier.”

We left that same evening, at around ten o’clock. My uncle knew a man a few miles away who would help us. When we got there, we knocked on the doors, on the windows. No one came. I was so tired that I fell asleep in the garden, in the children’s sandbox. My uncle sat waiting all night, worrying about the wife and three children he’d left behind.

In the morning, he hammered on the door again. This time someone answered. “Oh, you’re here. Come on in.” We spent the day in one of the bedrooms. At the end of the afternoon, the man came upstairs with a nervous look on his face. “My wife thinks you should leave, before the children get home. Our house is too small for us to hide people.”

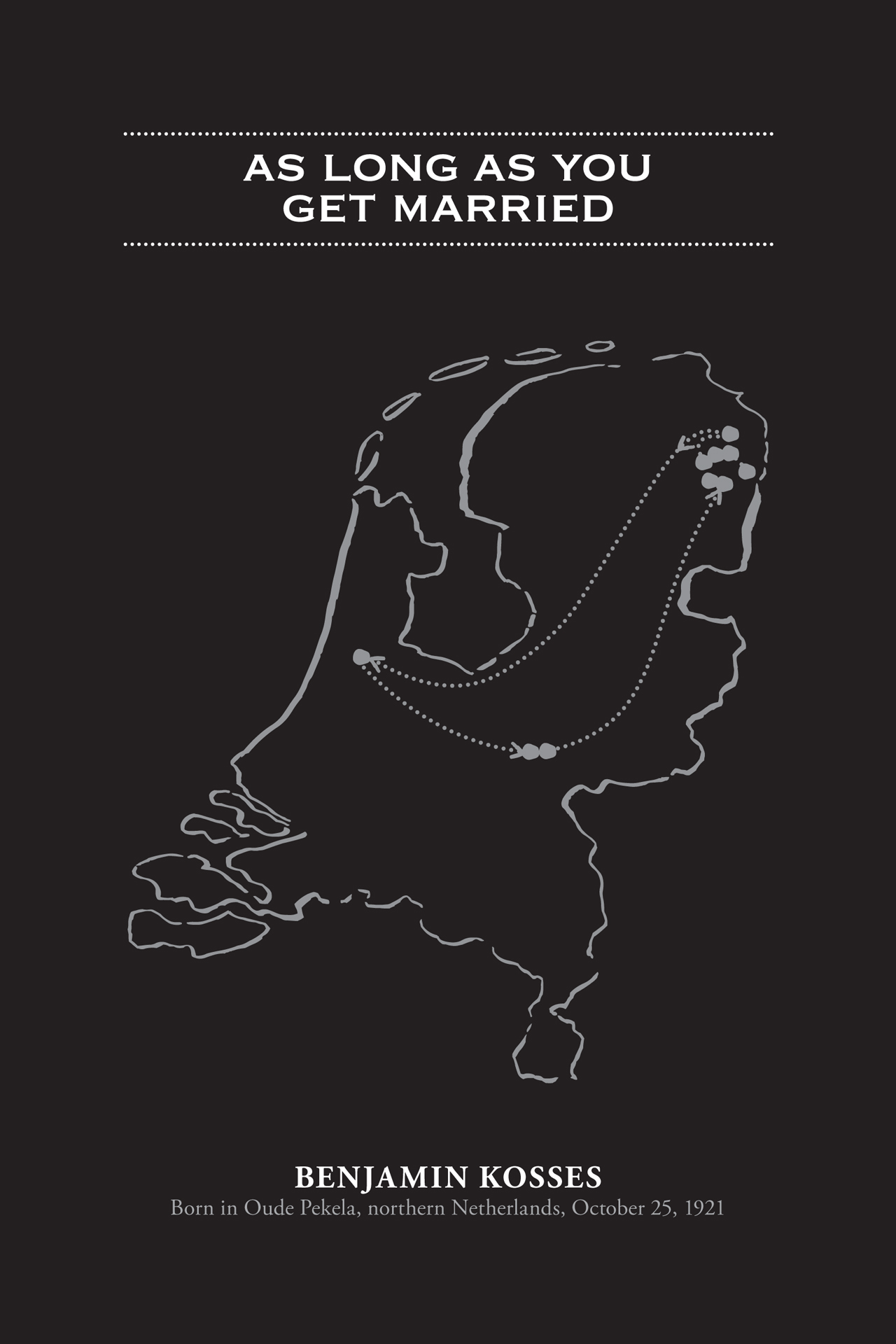

And that was our hiding place gone. It was a difficult time. I stayed at forty-two different addresses in three months. At first, I was still with my uncle, but after his wife and children had to go into hiding as well, that didn’t work. It was November 1942 by then, a bitter winter, and it was freezing cold. I remember walking through the fields, with no idea where to go. I knew there was a cattle shed nearby and they’re always warm. I found the shed, went inside, and lay down with the cows in the straw and fell asleep. The farmer found me in the morning, when he came to look after his cows. He knew who I was. “Fancy finding you in here!” he said. “How did you get in?”

“It wasn’t difficult,” I said. “The door was open.”

“Yes, we don’t lock that shed. You can stay in the house with us today, but make sure the farm workers don’t see you. You’ll have to leave when it gets dark.” I understood that he didn’t have the courage to take a Jew into his home, and at least I had a chance to sleep that day. I was able to warm up, and he gave me some food to take with me.

Then I went back to Nieuwe Pekela, to Hayo Kampion. He was a Jewish man, but he was married to a non-Jew, and so he was left alone. I knocked on the door, and Hayo answered. “Ah, come on in, son. Everyone’s been saying you’re in England.”

“If only! No, I’m still here.”

Kampion gave me some new clothes, which had belonged to his unmarried brothers who had already been taken away.

Another series of addresses followed. Finally I found myself with the Beuker family in Stadskanaal, a town just south of Nieuwe Pekela. They made me very welcome.

“You can milk and feed the cows, and work with the machines during the daytime.” They gave me a decent place to sleep. I hadn’t had it so good for ages.

A week later, the residential part of the farm buildings was requisitioned.36 It wasn’t so that Germans could live there but for NSB members who had come back from Germany. They’d hoped that the Germans would welcome them, but no one wanted them. “We’ll board up a corner of the attic for you,” said Beuker. “It may be for just another three weeks. By then the Germans will have lost the war.”

I was up in that attic for fourteen days, in a wooden box that they’d built along the slope of the roof. It was dark up there, and I had a bucket to do my business in. One evening they came to fetch me. The NSB people were out for the evening, so I could have a wash and eat with the family. At dinner I said to them, “I can’t stand it up there any longer. I want to leave.”

“If you really want to go, I know an address for you. I’ll go ask right now.”

Fifteen minutes later, he returned, “Get your bike and your things. I’m taking you to the Drenth family. There’s already a Jewish family there: a man, a woman, two children. You know them.”

The Drenth family’s house

The Jewish family staying with the Drenths turned out to be another uncle of mine, who was there with his wife and two children. I knew them well. But it wasn’t a warm family reunion. They immediately made it clear that I wasn’t welcome, that I was an intruder in their world, a room of just over two hundred square feet, which they would now have to share with me, night and day. After only a few days, we had an argument about the lessons he was teaching his children. It was nonsense. He was teaching them half German, half Dutch. We were both really angry, but then his wife said, “Nico, just let him do it instead.” So I started teaching the children math, Dutch, geography, and history, using schoolbooks that one of the Drenths’ daughters brought home from her school.

One evening, Mr. Beuker came to the house. He showed me a letter about the children of the uncle I’d been on the run with at first. They had to leave the place they were staying in Amsterdam. The money had run out. It was almost impossible for them to get hold of food and drink. “What should I do?” Beuker said.

“You’ll have to ask Drenth,” I said. “He’ll know how to handle it.”

Beuker went into the back room to discuss it with Drenth. I followed him, because I wanted to see what would happen. Father and Mother Drenth looked at each other and nodded. “You just bring them here.”

Well, that really upset the uncle who was already there. He said there wasn’t enough room for so many people, it was too dangerous, etcetera, etcetera. Until Mother Drenth looked at him and said, “These are your brother’s children we’re talking about.” That shut him up.

Other people came to stay at the Drenths’, including my sister, who had been hiding in henhouses with my parents, out in the countryside. But there was a raid and my parents were picked up. We never saw them again. My sister had been able to make a run for it just in time. She had a very good set of false papers that said she was a maid. She soon found it too cramped in that small space with us. She didn’t look very Jewish, and so she was used to going wherever she pleased. She left us and went out to work for various families instead.

Bennie’s parents with his sister Rebekka in the town of Voorthuizen, where they hid in a henhouse. They were betrayed in August 1943.

At one point, there were fourteen of us sharing those two hundred square feet. There were only two beds in the room, so at night we put sacks of straw and blankets on the floor. We got up early and kept to a strict schedule for washing and dressing, and we tidied the room before we went to bed so that it wouldn’t become a complete chaos.

Every morning Drenth used to fetch two big buckets of water from the canal that ran past the house. The farm had no electricity, no running water, and no indoor toilet. We washed ourselves with water from the canal in a bedroom with a washbasin and an old-fashioned jug. During the daytime you couldn’t go to the bathroom because you had to go through the whole house. We used a bucket instead. When the chairs were arranged around the table and everyone had washed, then we would each have a slice of bread for breakfast.

The Germans never raided the farm. They didn’t become suspicious because Father Drenth had come up with a clever plan. He saw an advertisement in the newspaper one morning from a NSB office that was looking for a junior clerk.

“You’re going to apply for that job tomorrow,” he said to Lammie, his eldest daughter. Then he went to see an old friend of his, an NSB member with whom he still got along well. “Listen,” he said, “could you explain to the people at the NSB office that my daughter has to have that job? She doesn’t have any work, and we’re not going to be able to manage at home for much longer.”

She got the job, and the wages too. That office was where they planned the raids. And that’s why we never had a raid at our house. Everyone in the village knew where Lammie worked. That made them suspect that the Drenths were Nazi sympathizers, and they would never have imagined that Jews were hiding at the farm. Their suspicions must have grown stronger after the director’s wife, Mrs. Vuurboom, said to Lammie, “Your mother must often be alone at home when your father’s out at work. I’d like to go over and have a cup of tea with her. It’d be nice to chat with someone for a while.”

“Then let her come,” said Mother Drenth to her daughter. “Invite her for the day after tomorrow.”

So Mrs. Vuurboom came to visit. She was sitting no more than ten feet away from our hiding place, drinking tea. And she just kept on chattering away, even after Mother Drenth should have started preparing the food. The local farmers had seen that woman come into our house, so now everyone was sure to think that the Drenth family were Nazi sympathizers.

Everyone except for one neighbor. One sunny day she saw Mother Drenth hanging out the washing. She came over and said, “You mustn’t do that. All of those things you’re hanging up there don’t belong to just your family. There’s no need to tell me what’s going on in your house, but you need to take that washing down, because if I can see it, other people can see it too.”

Around that time, in the middle of 1943, I started getting to know Lammie better. She used to run errands for us sometimes. Once in a while she would take a list to Groningen to do shopping. We would give her some money, and she would set off with a suitcase. She brought all kinds of things back to the house.

From half past eight in the morning until midday, I kept the children occupied with schoolwork, but you had to entertain them somehow after that was finished. One day Father Drenth and I made a mouse cage out of glass and wood. But we didn’t have any mice, so Lammie went to Groningen to get some. The mice went in the suitcase, together with all the other shopping she’d done that day, including some cake. The journey from Stadskanaal to Groningen was a long one, as it was an old-fashioned slow train. And on the way back, the mice nibbled away inside the suitcase. There wasn’t a crumb left of the cake!

On her trips to Groningen, Lammie’s old school friends beat her up a few times, as they couldn’t stand her going around with an NSB badge on her coat. When she got home, she was covered with bruises and her clothes were crumpled and torn. Her parents were too busy to worry too much about her. So we spent time together and we comforted each other. In that small space I shared, there were three married couples, two of them with children, but, like Lammie, I was on my own. I gave her a shoulder to cry on. When you’re comforting someone, you touch, and sometimes things happen. We fell in love and then we had a new problem: Lammie was pregnant. Mother Drenth thought it was dreadful, absolutely terrible. Her father had a more practical attitude. “As long as you get married later, when this is all over, it’s fine by me.”

We could hardly buy any things for the baby. Everyone knew Lammie was working for the NSB, so shopkeepers refused to sell anything to her. Finally we found one company, where the Drenth family had never spent a penny before, that was prepared to sell things to them. They bought diapers, baby clothes, a crib, and all the necessary bits and pieces, for not too much money.

The birth, on December 10, happened in the living room. The doctor, Father and Mother Drenth, and I were all there with Lammie. When our daughter came into the world, she immediately started screaming so loudly that it woke up all the children in the house. Of course they knew what was going on; they’d noticed Lammie getting rounder. We fetched them out of bed that night to show them the baby. That set their minds at rest and all five of them went back to sleep.

After the war, we got married, just as Father Drenth wanted. Our eldest daughter is now sixty-five.

May 8, 1945, Bennie and Lammie’s wedding day. Mr. and Mrs. Drenth (sitting on either side of Bennie and Lammie) with all of the Jews hiding in their home, and Mr. and Mrs. Brouwer, resistance workers who provided money and ration cards, back row, fourth and fifth from the right.