Lowina de Levie, 1937

I was always a nervous child. I wasn’t really teased or anything, but I never joined in with the other children in the school yard. I just used to stand and watch. My parents were always fighting, so I was too scared to take my friends home too.

We weren’t poor but we weren’t rich either. For lunch we had one slice of bread with some sort of topping, and the rest with plain margarine. My sister and I got a new dress twice a year. We thought that was plenty. I never minded that others in my class were better off. What I did mind was the bad atmosphere at home.

When war broke out, I was fourteen. I remember standing with my father and my eldest brother on the porch at about four or five in the morning. It was a beautiful night, a beautiful morning, but we could hear the drone of airplanes in the distance. I didn’t understand what was really happening for a long time — not when the war started and not even when we went into hiding in 1943.

One day my eldest brother was picked up. Fortunately he came back home, but it gave my parents a terrible scare. That fear infected me, and it only became worse as the war went on, particularly after we were made to move to a small apartment in the Rivierenbuurt neighborhood of Amsterdam. The Germans housed the Jews in two or three areas of the city to make it easier for them to carry out raids. During that same period we were made to leave school. I didn’t mind that so much. I’d just been held back a grade because I never did anything in school. All I did was draw. I used to draw pictures of happy families.

I had to walk half an hour every day to the Jewish School with my brother. I had a boyfriend at school, Jacques. We went skating together just once. He brought me home on his bike, and it was so windy that my eyes filled with tears. Oh God, I thought, why am I crying now, at this moment, when I’m so happy to be on the back of Jacques’s bike?

Then we were no longer allowed on bikes, or into shops, and we had to wear a star — but none of that made much of an impression on me. The worst thing was the fear. I was particularly scared in bed at night. If I heard any noise at all, I thought it meant Jacques was going to be taken in a raid.

Then, one day, the Gestapo appeared in the doorway of our classroom at school. They read out his name: Jacques B. He stood up and said, “I’m young and I’m strong. I’ll survive.” He was wearing a good pair of walking boots and he had a backpack with him.

I knew at the start of the war that I was Jewish and that it was mainly Jews who were being taken away, but I still felt safe at that time. I was more scared that other people would be arrested. That made sense, as my father had secured a job for me with the Jewish Council. Anyone who managed to get a job with the Jewish Council was temporarily exempt from deportation.

The job my father got for me, as a housemaid, is what saved me. One day I was working at the house of an old lady who lived in the Rivierenbuurt district. Suddenly I heard the doorbell. And then the men from the Gestapo came storming up the stairs in their gray uniforms. My papers were in order, so I didn’t have to go with them. The old woman did, though. They dragged her out of her bed and threw her into the back of an open truck. I have no idea if I slipped her anything to take along. Clothes or food. I can’t even remember if I said anything to her.

At home we had a suitcase full of clothes ready for if we suddenly had to go into hiding. It wasn’t meant for us to take if we were deported to the East — that was something we wanted to avoid at all costs. When I turned sixteen, I was no longer under my father’s protection. As far as the Germans were concerned, I was now an adult and at any moment I could be called for deportation separately from my parents. At that point, we all went into hiding. Non-Jewish colleagues of my father’s arranged the addresses for us. How they found them and how much it cost were subjects that no one mentioned, not even after the war. One thing was clear though: Money was necessary, and it was almost impossible for people without any money to go into hiding.

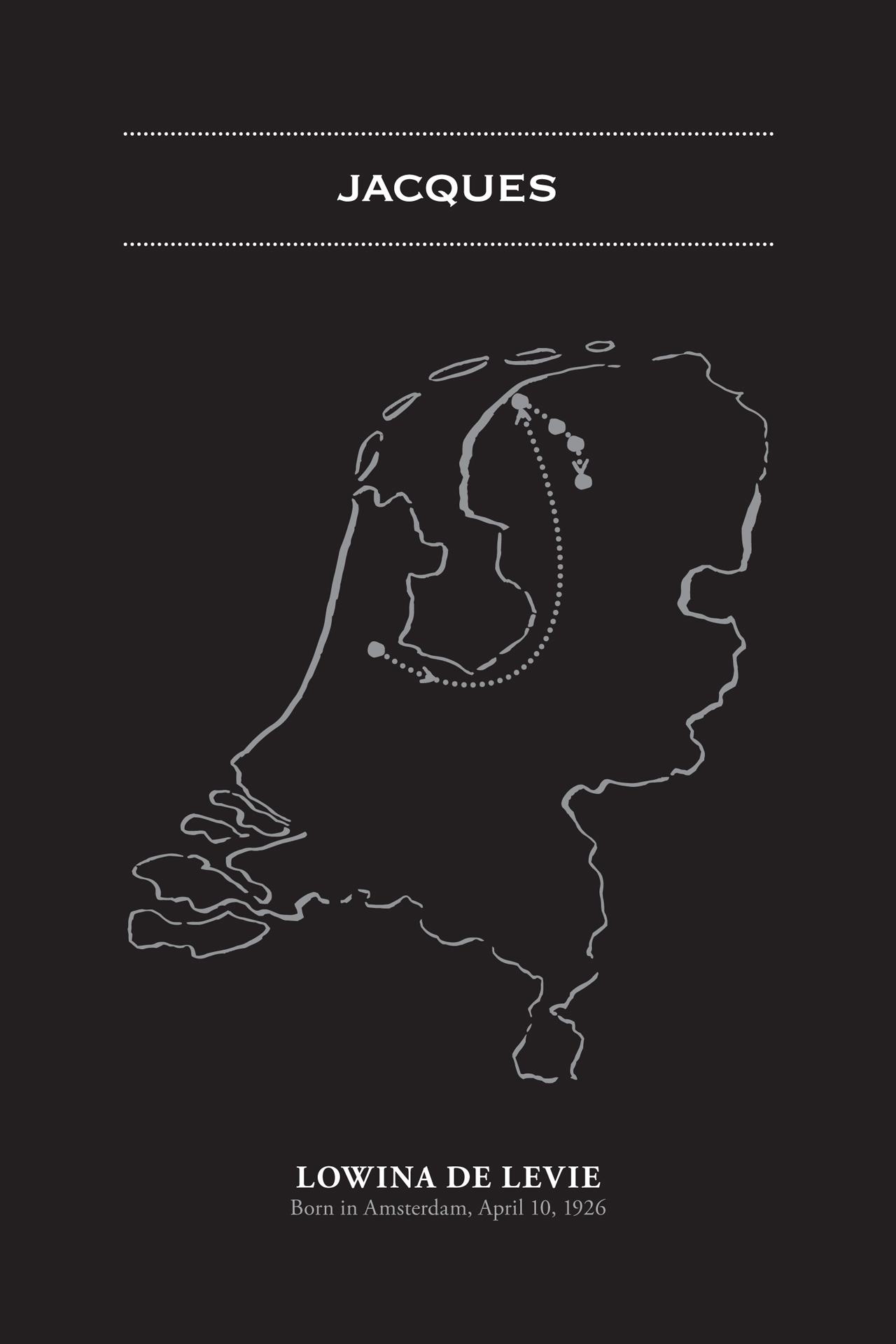

A woman who worked with my father took me to stay with a farmer just outside the village of Sint Jacobiparochie in Friesland. The farmer and his family had been living for years in a disused station on an old railroad line. They kept some pigs and a cow in a large room, which had probably once been the waiting room. I had a small room of my own up in the attic, where I could be alone.

I had no idea what living in hiding was going to be like. What I found most surprising was that there were places outside Amsterdam where a Jewish person could still have a nice life and people would treat you kindly.

The family had three children, a son who was a year younger than me, a daughter who was ten years younger, and a baby. I was really clumsy but, when the mother was ill, I still managed to look after the baby, cook the food, and run the household. They really needed me. I felt more at home there than anywhere else.

In Sint Jacobiparochie, where I did the shopping like any regular person, I was known as Loekie de Lange. The story we had to tell was that my sister and I had left Amsterdam because our mother was too sick to look after us. It was a strange story, because if our mother had been sick, we’d have been kept at home, since it was usual for girls of around ten years and older to take care of their mothers when they were sick. But the villagers were good people, not collaborators, and they never betrayed us.

About once every six months, my father’s work colleague used to visit. She brought letters from my parents, who were in hiding separately from each other. First she came to see me and then my sister, who was with a different family in Sint Jacobiparochie. Then she went to Limburg, where my brothers were in hiding. She stayed only one night, so I had to write like crazy to answer their letters. I told my parents that I was doing the housekeeping, and later I wrote to them about cooking on an electric stove for the first time, and the way the milk boiled over if you left it alone for just a moment.

It’s possible that the messenger also used to take care of the finances, because we had to pay for being in hiding. My father had already made preparations before the war. He had sold everything: furniture, piano, silver. I’ve always thought it was very clever of him to see what was coming and to take appropriate precautions.

In Friesland, the man who organized the addresses for people to go into hiding was a minister. One day, he came to the station. “I’ve been assigned to a parish in Bergum,” he said. “It’s some way from here, to the east of Leeuwarden. You and your sister can come and live with us.” It soon became clear that he needed help around the house. He had four children, the eldest of whom was four, and there was another on the way.

My sister was staying with a grocer and his family. She wasn’t allowed to do anything, so the move might be a good thing for her. But what about me? “Well,” I said to the minister, “I like being here, and they like having me. Perhaps you can find another girl.”

“But your sister can go to school if you come with us to Bergum.” That argument swayed me. My sister was twelve at the time, and it’s important to go to school at that age. I hardly even thought about my own education. I was just happy that I’d been taken in by a fairly relaxed family, where I didn’t have to be scared all the time of being caught and taken away.

I continued to resist, and he said, “If you don’t come, the family won’t get any more money or ration coupons.” That’s how it worked: With my fake identity card I got coupons that the family could use to buy food. Without those coupons, they could only buy food for their own family. And that wasn’t very much. That didn’t really matter to them, though. “You’re welcome even without any coupons,” they said. “If there’s food for five, there’s food for six.”

But finally I agreed to go anyway. The house in Bergum was large, and so was the family. They put me to work immediately. My sister was allowed to go to school, which was good. We had to tell that unlikely story about our sick mother in Bergum too, as it was the minister who had come up with it, but once again no one betrayed us.

Lowina with one of her brothers and her sister, 1935

The minister often used to get so furious that he would throw his children from one end of the room to the other. His wife had no say in anything. She had a baby every year — and that was it. When he sat in his study on Saturday writing his sermon, we all had to be as quiet as mice, even the really little ones. I was used to discipline at home, but it was really extreme. I ran the household and, although I disliked the family, and I wasn’t free to be myself, I still managed to fit in. I’d learned how to adapt by then. It had become second nature.

My sister was so nervous that she often used to wet the bed. Then the minister would shake her and hit her. And when he saw me watching, he used to lash out: “Oh yes, you’re the queen, aren’t you?” There was obviously something about my attitude or the look in my eyes that showed how much I loathed him. When she was in her fifties, my sister committed suicide. It must have been connected to all of the stress of our childhood.

At one point, some Germans were housed in the minister’s home. They were there to build bunkers, not to track down Jewish people, but I was still terrified. They often used to come into the kitchen with some chickens or a rabbit. The maid and I would prepare it for them. But I refused to eat any of it: I didn’t want to eat anything the Germans had caught or shot. The minister thought that was ridiculous. He couldn’t stand my attitude. He said it would be dangerous for everyone if I refused to eat the food the Germans had brought. That was nonsense, of course. The Germans didn’t eat with us, so there was no way they could see I wasn’t eating their food.

I was so scared when we were living with the minister that I went to see a local doctor. I assumed that, like everyone else in Bergum, he was a good man, not a collaborator. I explained that my sister and I were sleeping in a garden room at the minister’s house. “If the Germans ever raid the house,” I said, “can we try to escape through the garden and come to you?” He said that would be fine. I was looking for a refuge, even though we still didn’t have a clue what was happening to Jewish people in Germany and Poland. We thought you had to work very hard and they didn’t give you enough to eat, so that if you died it was of natural causes. I wrote and told my father how scared I was in that house. Six months later he replied to say that I shouldn’t be scared, but also that it made no sense not to eat their chickens. He said I shouldn’t worry so much. That was a big disappointment. I wasn’t able to talk to my sister about my visit to the doctor or about my fears. She was four years younger than me, after all. I felt so lonely.

Looking back, my fear was understandable. It wasn’t my refusal to eat “German” food that put us at risk. The minister himself was the real danger. Every Sunday he preached from the pulpit about what had been said on Radio Oranje40 that week, even though it was strictly forbidden to have a radio, let alone listen to Radio Oranje. And he talked about us, about the girls who were living in his house because of their sick mother.

It’s hardly surprising that the minister and his family eventually had to go into hiding themselves. That meant that we had to leave too. My sister went with a teacher from Bergum to the island of Schiermonnikoog, where the woman had been born. She was going back to teach there. My sister had a good time on the island. The teacher, Aunt Martha, became a mother figure for her.

A woman from an organization that helped people to find hiding places took me on the back of her bike to a minister in Drachten. A month later, the same woman took me to stay with a young farming couple, where a Jewish boy was already in hiding. He was two or three years older than me, and his name was Bram. When the farmer went to bed, he would say, “Why don’t the two of you stay here for a while?” On one of those evenings, I was introduced to sex. It was terrible. I didn’t like the boy at all, but I did it anyway. I felt so guilty, particularly because I was still thinking about Jacques, the boy from the Jewish School. I knew he’d been deported and that it was by no means certain that he was still alive, but I was ashamed because I had betrayed my own feelings. When it became dangerous to live with the young couple, I went to stay with an older farming couple in Jubbega. They had five children. The youngest, an unmarried daughter, still lived at home. Before the war, they’d been so poor that the farmer worked in Germany on weekdays. His wife was a sweet little old lady with a bent back. Summer and winter, she did the washing at four o’clock on Monday mornings, outside, on an old-fashioned washboard. They had never had much food, they had no comforts, and they had to work like dogs, but during that last winter of the war, when people from the west came knocking at the door to ask if there was anything to eat, they always had something to spare. They would shake their heads in amazement and say, “How is it that those city folk have no food?” They had a cow and a pig by then, so they were no longer as poor as they had once been.

Someone might knock at the door at any moment, and they were terrified that I would be discovered. “Go! Get out of sight!” they would shout when they saw anyone approaching in the distance. So in the daytime, I was only allowed to sit in the barn. It was a big, tall barn that they used for hay. I sat at a table by the door and I read. I left the door to the barn slightly open, for the fresh air, and to let in some light. I was allowed to stretch my legs a little in the evening, and I used to go for walks along the canal.

At night I shared the daughter’s bed. She worked in a library and she brought home all kinds of books for me. So I sat there in that barn, reading books in German, English, and French. It seemed like a good idea, as I knew I’d have to go back to school at some point.

I stayed in Jubbega until the end of the war, and I even started putting on weight while I was there, because all I did was sit around. The place was never raided by the Germans, and I was able to control my fear. After the war though, it was so hard for me to cope that I didn’t even think to thank the family. I still feel really bad about that. They’re long dead by now of course, and their daughter’s most likely passed away too.

I celebrated liberation in Friesland, in the town of IJlst, with Bram (the boy hidden at the farm) and his parents. The Germans had gone, which was wonderful, but I didn’t have much to celebrate, and certainly not with Bram. I still went back to Amsterdam with him later though, to my old flat, which was empty. I was even engaged to him for a while, because our parents said we should.

I can’t remember anything about my reunion with my parents and my brothers. My father asked for a divorce immediately after the war. When I heard, it was as though the floor beneath me cracked right open, like an earthquake. During the war, I thought that everything would be better later, at home and all over the world, and that we would all work together to build a new society. The divorce dashed all of those hopes. I felt completely alone. That feeling lasted for years.

In the years after the war, I became curious about all of my old classmates, particularly Jacques, but I was always too scared to try to find out what had happened to him. It wasn’t until thirty years later that I went to the Hollandsche Schouwburg in Amsterdam, where the Jewish people who died in the war are commemorated on the walls. I discovered that Jacques had been gassed in Sobibor, almost immediately upon arrival.