5.1 Participatory Culture and Remix

Stanley Grenz (1996) argues that the postmodern view of life can be conceptualised as a theatre production, ‘an assemblage of intersecting narratives’ (loc. 555). What at first may appear to be disconnected stories become a summarisation of globally historical events. This is distinctly evident throughout life within webworking culture. Instantaneously spread messages create surges of ripple-effects. People respond predominantly through their written comments, but as technology and the ways to utilise it continue to improve, the written word is giving way to other modes of representation. As a result of user-friendly digital media, people now can embed their individual thoughts into images by remixing widely known content and if they choose, adding their own personal representations, thus, extending and inserting themselves into an embodied larger whole.

[…] relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement, strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations, and some type of information mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices. A participatory culture is also one in which members believe their contribution matter, and feel some degree of social connection with one another. (Jenkins et al. 2006, p. 3)

The participatory culture is thus a melting ‘pond’ where an ongoing bubbling and rippling mix together cultural, physical, professional, educational collective and individual hierarchies and disintegrate high-low social extremes. The participatory compass is guided by either our desire to resist or our passion to support something. Driven by these inclinations, people actively jump into the shared pond, remixing the collective with the personal and believing that what they are doing is their right and is important.

[…] the far-reaching spread of post-production tools (available to almost anyone who has at least a computer) that allow for sampling and the overlapping of sources at a rate that would be simply unthinkable just 30 years ago. (p. 72)

The digitalisation of culture (the tendency to bring all analogically produced human culture into the digital domain) is one of the dynamics that has most encouraged the emergence of remix culture, to the extent that it is today possible to say that ‘humans have never had so many materials in their hands’ which is to say: so many materials to remix. (p. 73)

In other words, a pervasive remix, as ‘we are now encountering,’ became possible through the introduction of digital technologies (p. 71). One of the fundamental characteristics along which new digital media operates, with numerical representation and automation, is modularity—the ‘fractal structure of new media’ as it has been identified by Manovich (2002, p. 30). Manifested through primary discrete elements such as ‘pixels, polygons, voxels, characters, scripts’ (p. 30), modularity allows the structural independence of the parts in the digital objects and assemblages, the construction of numerous variables and the transcoding of digital compositions.

[…] the simplicity of remix operations, the movement toward digital media, and, above all, media modularity , as noted by Manovich, prelude a progressive hybridisation of visual languages and, therefore, a state of ‘deep remixability’ (or total remixability), a condition in which everything (not just the content of different media but also languages, techniques, metaphors, interfaces, etc.) can be remixed with everything. (p. 73)

For cinematic writing, it is important to identify three types of hybridisation in contemporary cultural practices.

First is the cinematic writing association with the remix of DJ applications of music, which originated in the late 1960s and 1970s, and then spread in the 1970s and 1980s as a subculture in the United States and Europe. From the mid 1980s to mid 1990s, it became a popular music style (Navas 2012, p. 20).

Second is meme that was invented ‘by Richard Dawkins in 1976 to describe small units of culture that spread from person to person by copying or imitation’ (Limor 2014, p. 1). At the present time, memes are generated by netizens who remix images found mainly on the Internet. Two fundamental attributes of memes are that they are applied to express jokes, satire or rumours and that they portray a complex intertextuality, remixing concepts, ideas and images in smart, surprising and novel ways.

The third type of popular remix is expressed through vidding . This is a craft of remixing, mainly YouTube videos. Fan vids, as Henry Jenkins (2012) observes, ‘are more apt to be melodramatic or romantic than comic: vidders want to get closer to the characters rather than to hold the text at a distance’ (loc. 622). Another trait in vidding that Jenkins identifies is that is becoming increasingly political, tackling such issues as gender, race, and inequality.

In identifying the type of remix proposed for cinematic writing, we re-examine Manovich’s concepts of modularity (2002) and deep remixability (2013). The term deep remixability term emphasises ‘complex forms of interactions’ that include remixes among techniques within a specific media content as well as a ‘crossover effect’ (p. 272); that is, remixing between various types of media. From this point of view, all three categories of remix described above—remix, meme and vidding—can be subjects for being remixed in cinematic writing. Deep remixability shows that ‘new media follows, or actually runs ahead of, a quite different logic of post-industrial society—that of individual customisation’ (Manovich 2002, p. 29).

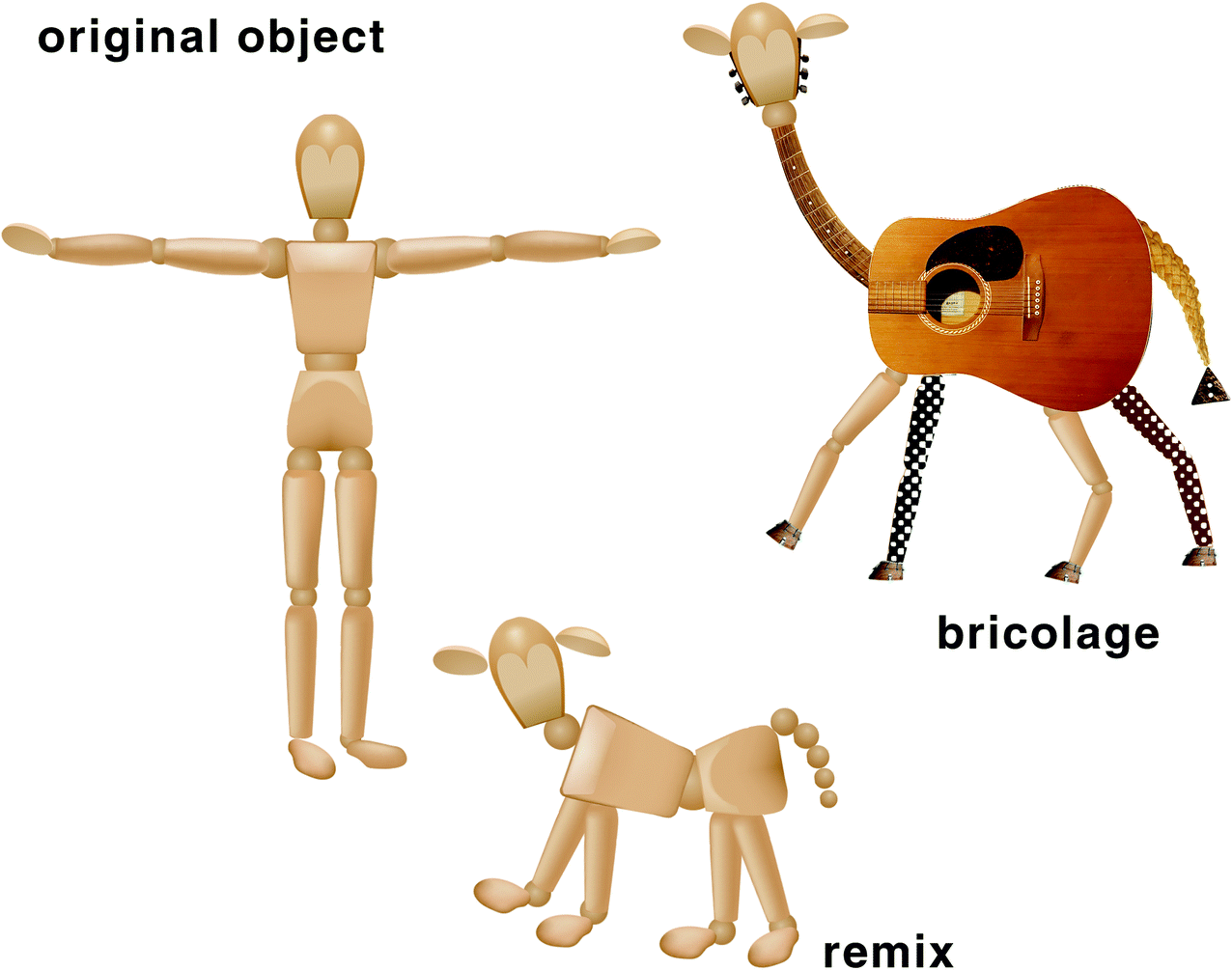

Visualisation of remix and deep remixability —bricolage outcomes

By means of digital modularity , the original object, for instance, a wooden model of a human, can be reassembled into a new configuration – a wooden model of a dog. This is an example of remix.

In the knowledge-production approach discussed in this text, deep remixability is associated with bricolage . It manifests itself through remixing the elements from disparate fields of knowledge or representations. To the image-example shown above and labelled as bricolage can be added audio and animated elements.

Bricolage in the case of the knowledge-production process is characterised as a methodology of mapping across diverse domains and making new meaningful reconfigurations.

[…] in order to survive the rat race, one has to become active, inventive and resourceful, to develop ideas of one’s own, to be faster, nimbler and more creative – not just on one occasion, but constantly, day after day. Individuals become actors, builders, jugglers, stage managers of their own biographies and identities and also of their social links and networks […] Living a life of one’s own therefore means that standard biographies become elective biographies, do-it-yourself biographies … (loc. 748)

Individualisation […] means de-traditionalisation but also the opposite: a life lived in conflict between different cultures, the invention of hybrid traditions. (loc. 787)

The privatisation of post-production tools engenders a ‘do-it-yourself’ type of hybridisation. The media hybrids are no longer cultivated by ‘cross-breeding’ inside professional companies. They are generated every day and everywhere to assert individuality and to make personal biography important in the global scheme of things.

5.2 Remix and Do-It-Yourself (DIY)

The new hybrid aesthetics exist in endless variations but its basic principle is the same: juxtaposing previously distinct visual aesthetics of different media within the same image. This is an example of how the logic of media hybridity restructures a large part of culture as a whole. (loc. 4416)

Hybridisation is an outcome of recombinational activity that spread globally, affecting both the content and form of circulating information and establishing a new cultural movement that has been termed ‘remix culture’ (Navas 2012, p. 14). The appropriation of existing materials in ways that are more often amateur than professional in nature has brought an atmosphere of casualness and sketch-like performance to the digital landscape. In images, such examples can be often observed in rusty and paint-splattered backgrounds, sponge and spray effects and eroded texts, misaligned objects and unbalanced compositions, as if they are in transition, in ‘renovational’ exploration—a disintegration achieved with new media tools before a more refined solution will be found.

Artists have always, as McLeod (2015) asserts, ‘borrowed from each other and have been directly inspired by the world that surrounds them’ (p. 84). The widespread use of digital technologies and the prevalence of the Internet as a social medium of communication from the late nineties, however, opened an absolutely new era for creative practices. Navas, Gallagher and burrough (2015) write that the idea of remix is closely linked to do-it-yourself (DIY) practices (p. 1). The concept of widespread DIY is important to cinematic writing in the sense that it is considered ‘as a mass phenomenon; that is, the masses participate rather than only artists’, when people perform ‘a series of activities […] without the aid of professionals, and often without any specialist knowledge’ (Campanelli 2015, p. 74).

In this regard, the specifics of DIY, ‘which denotes a way of thinking and working halfway between the concrete and the abstract’ (p. 74), are aligned with the ontology of cinematic writing where creativity is manifested by DIY aesthetics. The new meaning emerges through what McLuhan saw as the ‘fruitful meeting of senses’, or cross-fertilisation of senses where taste can be explained with colours, typography can sing a song expressed through rhythm and various typefaces and movements of objects can interpret time and the character of the story. In other words, cinematic writing suggests the appropriation of digital media in a full and precise meaning of the concept of deep remixability, which allows the knowledge-maker to collect and remix what was previously incompatible. The representation of reality in cinematic writing is built on examining producer’s own mind and meaning is developed from interpreting an individual mind-movie projector.

5.3 DIY and Multimodal Bricolage

As discussed, deep remixability is defined by remixing a wide range of elements from various digital modes of representations, techniques and styles and other categories of popular remix genres. Such a reconfiguration of elements drawn from heterogeneous resources is distinctive of a traditional activity practised in France called bricolage. The term bricolage is borrowed from the French anthropologist Lévi-Strauss (Maxwell 2013, loc. 971). Referring to Lévi-Strauss, Maxwell portrays a bricoleur ‘as someone who uses whatever tools and materials they have at hand to complete a project’ (loc. 971).

According to Grenz, art purists find bricolage, an assemblage of elements from eclectic resources, distasteful ‘on the grounds that it violates the integrity of historical styles for the sake of making impression in the present’ (loc. 448). Nevertheless, postmodern expressions seek exactly that: to frustrate the canonical artistic approaches that breed static definitions of the world and instead attempt to create dynamic representations of the complex and forever changing reality.

The same can be said in relation to bricolage as a system for knowledge-making. Rogers (2012) denotes bricolage as ‘methodological practice(s) explicitly based on notions of eclecticism, emergent design, flexibility and plurality’ (p. 1). Rogers, Denzin and Lincoln (2013) see bricolage as an eclectic and political approach to inquiry. Kincheloe and Berry (2004) articulate bricolage as a critical constructivist praxis (p. 2). With respect to ‘the complexity of meaning-making processes and contradictions of the lived world’ (Rogers 2012, p. 4), bricolage embraces the eclecticism of the individual, reflexive approach ‘to pursue the realisation of themselves (self) through diverse means chosen on the basis of unique, subjective experiences’ (Altglas 2014, p. 4).

Framed as an approach to knowledge-production, multimodal bricolage is therefore an analytical patchwork compiled from heterogeneous resources, where documentation of the process and the construction of knowledge is achieved with cinematic writing. In relation to the cultural practice of deep remixability, multimodal bricolage extends its remixability beyond the digital and into the physical domain. This is one of the central tenets of multimodal bricolage methodology. It proposes that the producer of knowledge, who is historically privileged with possessing personal tools of knowledge production, moves into a domain of complexity and learns from the full spectrum of the world around them, including natural, sociocultural and digital environments. The task of the bricoleur is to foster his/her natural curiosity for, and appreciation of, the air he/she breathes, the water he/she drinks, the sun he/she enjoys, the people he/she lives and communicates with, the traditions that tell him/her who he/she is, the unlimited catalogue of information supplied by the Internet, and the extraordinary smart tools that no one in the history of the world before the digital age had and could utilise the way he/she can at present. This grants the younger generations an incredible authority that also comes with responsibility: responsibility for the air, water and people who live on earth, as well as the use of the Internet data and tools that no one before them has had at their disposal. They have the responsibility of addressing these issues in full awareness of their biological, social, physical, intellectual and technological unity and have to develop a genuine concern for their sustainability.

In relation to deep remixability, multimodal bricolage addresses one of these concerns by imposing restrictions on its miscellaneous repertoire. The limitation is established out of respect for international copyright law that grants the producer of an original artwork or intellectual body of work the absolute right to its possession and use. This means that as easily as one can access an abundance of images, audio and video resources on the Internet to create remixes, memes or vids, the bricoleur generates his/her own database of resources by drawing on the surrounding world. If the bricoleur uses the information, ideas, conceptual constructions or facts borrowed from other people, this must be properly acknowledged.

The rule of bricolage, that is, of an amateur tinkering with ideas and objects, working with hands and using ‘devious means compared to those of craftsman’ (Lèvi-Strauss 1962, p. 16), reinforces the notion of the privately atypical rather than standardised nature of ideational practice. Managing ‘to make do with whatever is at hand, materials and tools that have not been designed and manufactured for a specific task but rather come from a bricoleur’s private stock and collections, means that they are saturated with certain meaning associated with the personal story of the producer. ‘They each represent a set of actual and possible relations; they are “operators” …’ (p. 18) that enhance the possibilities of realising self-expression with multimodal bricolage. The personalisation is advocated here not for the sake of sheer self-assertion but as a prerequisite for a rigorous knowledge production.

In contemporary culture, DIY is linked to the concept of home improvement. In other words, a bricoleur is a dilettante who fiddles with whatever is at hand in order to improve that which is meaningful to his/her direct surroundings. Through recursive loops, from doing to examining, the bricoleur explores personal choices, experimenting with ideas and tools in existence and those connected to the suitability of the intended purpose. The process of re-assembling that which already exists in ‘a private universe’ is a process of reflecting on what it means for the knower, and the process of putting together new assemblages for private use is a process of acquiring new knowledge about the world through learning about yourself.

This circularity, this connection between action and experience, this inseparability between a particular way of being and how the world appears to us, tells us that every act of knowing brings forth a world […]

All doing is knowing, and all knowing is doing. (p. 26)

Working with digital media, Barbatsis (2005) describes bricolage as a process of doing

knowing through organising new compositions ‘where the sense-making activity is patterned by working with bits and pieces … building them up, sculpturing a whole’ (loc. 8253). In elaborating on the bricolage principle of insight generation, Barbatsis draws an analogy with the principle of mosaic construction that results in ‘complex seeing’, the ‘collision of fragments and layers’ (loc. 8265). According to Barbatsis, bricolage is conceptualised as a ‘new media’ method of digital assemblages of ‘video, film, and computer screens, as well as multidimensional imaging’ (loc. 8253).

knowing through organising new compositions ‘where the sense-making activity is patterned by working with bits and pieces … building them up, sculpturing a whole’ (loc. 8253). In elaborating on the bricolage principle of insight generation, Barbatsis draws an analogy with the principle of mosaic construction that results in ‘complex seeing’, the ‘collision of fragments and layers’ (loc. 8265). According to Barbatsis, bricolage is conceptualised as a ‘new media’ method of digital assemblages of ‘video, film, and computer screens, as well as multidimensional imaging’ (loc. 8253).

5.4 Eclectic Personal Choices

According to Manovich (2002), the avant-garde aesthetic strategies of the beginning of the twentieth century have been instantiated through computer logic (loc. 283). Artistic styles such as collage and photo or movie montages have been crafted with cut and paste, layered elements and remix techniques. The digitisation of these techniques from manual to computer based is a demonstration of ‘transporting’ the creative experience from ‘real’ studios into virtual studios. The screen in this case is an interface: a portal through which the mind travels back and forth constructing and embodying meaning. On top of the cut and paste, layered production and remix techniques, there are many other new techniques that have been added as affordances of new media. For example, ‘the new ability to combine multiple levels of imagery with varying degrees of transparency via digital composing’ (Manovich 2013, loc. 4868). With the adjusted transparency of the layers, the objects’ appearances are modified in accordance with a wide-range of manipulation options offered by creative software, which leads to unpredictable effects that can kindle various emotional responses and result in an imaginative method of interpretation. The notion of imaginative knowing is epitomised in Lévi Strauss’ understanding of the technical plane in research, which he calls ‘prior’ rather than ‘primitive’ (p. 16). He sees it as a space where ‘mystical thought’ meets with ‘intellectual reasoning’. To Lévi-Strauss, the nature of bricolage is mytho-poetical such as ‘raw’ or ‘naive art’, ‘originally inspired by observation’. This is the ontological essence of bricolage, where aesthetics is a channel for an intuitive thought to become evident and then be intellectually refined to the emergent pattern of meaning. The bricoleur is therefore a scholar dabbling in the dilettante aesthetic producing an intellectual body of work.

Lévi Strauss’ further discussion illustrates the difference between the work of a bricoleur and an engineer in the way that the engineer first ‘questions the universe’ and then, in order to find a solution, ‘cross-examines his resources’ (p. 12). In contrast; the bricoleur’s first ‘practical step is retrospective’. He/she collects ‘the oddments left over from the previous endeavours’ and examines his/her resources as if looking ‘for messages’ ‘which have been transmitted in advance’ (p. 13). By assembling and re-assembling the motley of collected items, the bricoleur begins to recognise and finally interpret the message ‘according to their blueprints […] in making sense of their own experience’ (Jenkins 2012, p. 26).

Altglas (2014) distinguishes bricolage as a platform for making eclectic personal choices that results in ‘individuals’ liberation from collective norms and values’ (p. 4). With the use of bricolage as a methodology for knowing, people can ‘pursue the realisation of themselves through diverse means chosen on the basis of unique, subjective experiences’ (p. 4). Bricolage allows people to be guided through ‘an increasingly important quest for self-fulfilment’ through self-reflective approaches that are free from ‘the dictates of various institutions’ (p. 4).

In this context, multimodal bricolage follows the principle that ‘knowledge is strictly tied to the individual knower […] The observer is the point of fixation for all the divergent interests’, as Poerksen (2004) states (loc. 83). Therefore, cinematic bricolage was explored through the process of self-reflection. Based on the premise that the generated knowledge is the embodiment of the bricoleur’s mind-cinema running through the ripplework of life (loc. 83), cinematic bricolage follows two aphorisms:

Anything said, is said by an observer (Maturana and Varela 1980, p. xix); and

There is no knowledge without a knower (Kincheloe 2003, p. 48).

5.5 The Methodology of Collecting and Reassembling

We need only recall what importance a particular collector attaches not only to his object but also to its entire past […] All of these – the ‘objective’ data together with the other – come together; for the true collector, in every single one of his possessions, to form a whole magic encyclopedia, a world order, whose outline is the fate of his object. Here, therefore, within this circumscribed field, he appears inspired by them and seems to look through them into their distance, like an augur. (p. 207)

Upon pondering this quote, I borrow from Sirc (2004), who envisions collected objects being put in ‘a collector’s box’. Sirc writes: ‘so, text as box = author as collector’ (p. 116). If the collected objects represent the chaos of memories, then Sirc continues: ‘The challenge for the composer is to capture that memory-laden thrill for the viewer, inventing a uniquely visionary world from carefully chosen fragments of the existing one’ (p. 116).

[…] making new meanings from found physical objects and texts by placing them alongside things that you make yourself in order to “echo concerns and styles,” find some markers of identity, and communicate them. If we map this practice with real physical objects onto virtual, we can think about how meanings are made in digital media using, sounds, text, images, and clips. (loc. 158)

Potter sees this ‘emergent literacy practice’ as active curatorship, an approach that utilises the affordances of new media to make meanings through the intertextuality of different resources (loc. 167). ‘The concept of “intertextuality”, therefore, becomes an important additional frame through which to view media texts […]. There are echoes of the “mosaic of quotations” invoked by the semiotician Julie Kristeva to account for and define intertextuality ’ (1941, pp. 26–27).

In bricolage, intertextuality is expressed in a rich enmeshment of digital bricole s. Like for Benjamin’s ‘true collector’, the bricoleur’s task is to become inspired by the objects, the frames, the concepts in the collections, to learn to see ‘through them’ beyond time and space and pick up the quintessence of possible associations or clues, to reach an intended purpose and create a meaning that was not seen before.

For a knower engaged in traditional learning, attention to hints or possibilities may appear unnecessary interruptions of rationality. But perhaps, it should be seen not as an interruption of rationality, but as an interruption of the traditionally imposed linearity of thought. This is as if walking through an unknown landscape and seeing a rock indicating a detour. If the detour is taken with curiosity (instead of frustration), the circuit may offer an unexpected finding, a new perspective from which the whole area could be best seen or some original insight on how the landscape could be explored. Even asking a simple question, Why is the rock there? may lead to a fascinating discovery. Accepting that the environment not as a flat surface filled with obstacles, but is a rich habitat offering endless possibilities for discovery —only if the offers are accepted—provides the knower with guidance and resources in rendering their quest more engaging and rewarding. Curiosity, intuition and reliance on the individual abilities become extensions of mind, conduits through which knowledge is being generated and produced.

In view of this, Gregory Bateson’s (1972) analogy of a blind man with a stick comes to mind. The stick is an extension of the man’s mind; it is ‘a pathway along with differences [that] are transmitted […] a part of the systemic circuit which determines the blind man’s locomotion’ (p. 318). The man does not walk in absolute obscurity. He operates on the continuous evaluation of the touches of his stick on the pathway. The signals he receives ‘are not just impulses but information. The network of pathways is not bounded with consciousness but extends to include the pathways of all unconscious mentation’ (p. 319).

The stick, similar to McLuhan’s concept of typography, becomes a mind-cinema projector. Every touch on the path provokes mental grasps through a gestalt of sensory perception: hearing, the feel of a surface, sensing a distance, gaps between the moments of touch, and so on. Each is grasped and framed in accordance with the previous frame. One after another the frames roll in the man’s mind, converting sensations into an abstract system of signs personal to him that he uses to sketch the topography of the path in his mind. The cinematic bricolage’s knower may enjoy twenty-twenty vision, but to produce knowledge, visual acuity is not sufficient. One must transcode what he/she sees into the mind-cinema to give it an abstract form by organising it inside a conceptual frame constructed in accordance with personal associations and existing knowledge.

This analogy is helpful to better understand the process of the circularities between the events of physical activity

abstract constructions. In cinematic bricolage, the dynamics of this circularity are constructed with the agentic qualities such as curiosity, intuition and self-reliance as well as the material component of the activity, such as digital media. The material constituents of bricolage are also databases of elements: bricoles. Together, they constitute the matter and energy of the feedback loops, the flow which is determined by the affordances of digital tools.

abstract constructions. In cinematic bricolage, the dynamics of this circularity are constructed with the agentic qualities such as curiosity, intuition and self-reliance as well as the material component of the activity, such as digital media. The material constituents of bricolage are also databases of elements: bricoles. Together, they constitute the matter and energy of the feedback loops, the flow which is determined by the affordances of digital tools.

The task now is to search for ways in which ‘to open new media to writing’, as Wysocki (2004, p. 5) puts it; that is, to find explanations and strategies for the processes when ‘the human and non-human actors are involved in a medial relation to each other’ and the result of these interactions is ‘a human and machine cognition intermesh’ (Hayles 2012, p. 13).

The meshwork of multimodal bricolage with

cinematic writing

, in this matter of

cinematic bricolage

, becomes an epistemological platform for bringing to conscious reflection the foundations of human

agency

computer materiality enmeshment within the process of knowledge production.

computer materiality enmeshment within the process of knowledge production.

[…] is little or nothing that bridges those two categories to help composers of texts think usefully about effects of their particular decisions as they compose a new media […] to help composers see how agency and materiality are entwined as they compose. (p. 5)

In 2017, despite the widespread scholarly debates on how technology should be used to communicate learning, as far as my personal observation goes, there is still little discussed or written about the metacognitive mechanics of this circularity.

5.6 Cinematic Bricolage Mechanics

The epistemological orientation of cinematic bricolage (CB) develops as a consequence of complex systemic feedback loops cultivating a ripplework of human and digital media cognition. For example, the learning task starts with taking a photo with a mobile phone. Let us assume that this is a photo of the hands of a grandparent.

The photo is placed inside the digital page. Different students may be curious about different aspects of the image. Some can be interested in the story that the hands ‘can tell’ and within the story, they may be drawn to certain aspects they like to decipher linking the photo of the hands with life events. They may emphasise certain visual features of the hands by enhancing visual effects of the photo in Photoshop, cropping or distorting the image, or taking photos of other people’s hands for comparison. Technical manipulations of the photograph produce new questions and provoke new curiosity. Students may become interested in the questions of social relationships, cultural traditions, issues related to ageing, and so on. Every digital operation provokes a new mental grasp that in turn determines further movements in the progression of knowledge construction. Recording answers to their questions, hearing songs from the grandparent’s youth, taking photos of the things they have done by their hands, gathering more material about certain aspects of their interests from the Internet, interviewing experts, and initiating social media discussions become a heterogeneous repertoire of the resources that stimulate the production of an intertextual and multimodal knowledge outcome.

Two forms of cultural interpretation, database/paradigmatic (text, photos, sounds, moves, drawing and so on) and narrative

syntagmatic (images manipulations, fragments organisation, space/time coordination) become systematic feedback loop entanglement. It evolves through the dynamic circuity of stimulus

syntagmatic (images manipulations, fragments organisation, space/time coordination) become systematic feedback loop entanglement. It evolves through the dynamic circuity of stimulus

response dimension that, for example, the photo produces in relation to the information that was obtained via the Internet as well as flashes of memory that this relationship has evoked. This results in the framing of mind-grasps and the mind-cinema rolling.

response dimension that, for example, the photo produces in relation to the information that was obtained via the Internet as well as flashes of memory that this relationship has evoked. This results in the framing of mind-grasps and the mind-cinema rolling.

The producer represents the rolling of the mind-cinema as a series of overtonal montages, which are embodied as unified projections of the software layers. Even if the writing and objects are technically placed on the same layer within creative software, they are still organised by the principle of being either in the front or behind other objects, thus, layered. The unified projection is an ongoing transformation that results from the feedback loops as new elements are added and new ideas introduced.

experiencing cannot be realised within disembodied conditions. He writes:

experiencing cannot be realised within disembodied conditions. He writes:The centrality of human embodiment directly influences what and how things can be meaningful for us, the ways in which these meanings can be developed and articulated, the ways we are able to comprehend and reason about our experience, and the actions we take. Our reality is shaped by the patterns of our bodily movement, the contours of our spatial and temporal orientation, and the forms of our interaction with objects. It is never merely a matter of abstract conceptualisations and propositional judgements. (loc. 206)

In other words, CB takes a view of the mind similar to what Malafouris (2013) describes as ‘embodied, extended, and distributed rather than “brain-bound” and limited by skin’ (p. 6). The construction of knowledge takes place through the collection of bricoles, and their disintegration and reorganisation intertwined with written discussions. As these actions evolve through a choreography of feedback loops and rolling of the mind-cinema, they may bring into existence forgotten moments that are saturated with sensations and with understanding the knower’s place in the web of collective story. As Kalantzis and Cope (2012) put it: ‘Learning is the process of coming to know, not just in the conventional sense of getting knowledge into your head but also in the sense of learning to do and learning to be in the world’ (p. 219). Representation through multimodal metaphors allows further development ‘to retain, manipulate, and transform the world around us mentally using non-verbal code of mental images’ (Sadoski and Paivio 2013, p. 28).

The activity in this case is a mediator of knowing-how to do things and knowing-that we are in the world. Therefore, in promoting deep multimodal remixability, CB fosters the kind of human agency that is enmeshed with the physicality and materiality of the world.

5.7 Convergent Points

This chapter introduces the concept of multimodal bricolage, a system of knowledge-making based on an eclectic approach and a design that evolves through intermediary recursive circularities.

The feedback loops are a dynamic force that remixes and reassembles heterogeneous data, bricoles, into an expression of produced knowledge. This intention-guided intellectual multimodal manipulation of data, identified as bricolage, is congruent to an individual knower’s subjectivities. It is documented and negotiated within the digital pages of publishing software by means of cinematic writing. Due to the interdependent, circular dynamics between multimodal bricolage and cinematic writing, the terms are fused into cinematic bricolage.

CB is characterised by the deep remixability of the elements drawn from heterogeneous resources, domains of study, theoretical concepts, techniques, digital and analogue activities and artefacts, and visual, audio and motion components. Because it expresses meaning through the embodiments of symbolic components, CB can be seen as a do-it-yourself (DIY) activity. Rather than relying on experts’ knowledge and skills, which in the case of the mainstream education is ready-made and recognised as an authoritative set of recourses, the CB knower is positioned as an amateur agent of knowing.

compatibility with their personal intellectual abilities;

congruence with their natural, social and cultural circumstances;

conduciveness to the cultivation of their innate traits for inventiveness; and

understanding the best individual ways for intermeshing their logic with the digital media logic.

These personalised categories of learning are tightly linked to the notion of embodied mind and making meaning through circuity between rational thought, emotions and sensory-motor experiences. From this perspective, the aesthetics of CB are rooted in the subtext of embodied meaning, in the overtonal montage of the multimodal elements showing ‘how meaning grows out of our transactions with our environment’ (Johnson 2007, p. 16). Because emotions and sensory-motor experiences are highly private they influence the embodiment of meaning into an individually unique expressions.

Cinematic Bricolage system of knowledge production

Cinematic Bricolage —knowledge-production methodology | |

|---|---|

Data gathering resources | • Natural world • Social spheres • Cultural/subcultural groups • Internet (digital libraries, blogs, websites, social media) |

Data gathering tools | Digital • Mobile phones • Mobile tablets • Internet • Digital libraries • Scanners • Printers |

Analogue • Science equipment • Household objects • Outdoor objects • Art/craft tools • Field trips equipment | |

Data gathering methods (bricole s) | Video/Audio recording of: • Interviews • Experiments • Constructions • Plays/Performance/Music • Art projects • Social projects • Trips • Observations Photographs All above as well as scanning old photographs, old publicity items and artefacts |

Data Storage | Digital bricoles are stored in folders and sub-folders under various categories inside an ongoing project’s folder. They constitute a database of the knowledge-production resources |

Data analysis | Is performed in Adobe InDesign by means of cinematic writing—writing with images, sounds and movements Data analysis is carried out through recursive feedback loops that connect data gathering and data analysis into an intermeshed process Ongoing developmental stages of the data analysis are periodically negotiated in small groups (whether it is an individual or collective project) |

Data synthesis / Knowledge production | Is completed and presented within multiple pages of Adobe InDesign document. Every page of the document is an individually documented process of experimentation, analysis and knowledge constructions |

Key terms | |

|---|---|

Bricolage | – Something that is ‘patched’ together from a ‘whatever is at-hand’ repertoire |

Cinematic bricolage (CB) | – A system of knowledge production concerned with collecting data from heterogeneous resources, reconstructing, analysing and recombining data by means of deep remixability and digital embodiment through writing with images, sounds and motions |

Do-it-yourself (DIY) culture | – A counter movement to mainstream culture, looking for ways of living, thinking and doing without the assistance of the paid professionals |

DIY aesthetics | – Creative expressions focused on individual amateur rather than the skilled-developed production of meaning using a repertoire of resources available to a producer of meaning |

Embodiment | – Representing thought or meaning by means of a semiotic system |

Embodied mind | – The mind that is rooted in bodily processes. All of the properties of mind can be critically examined in relation to bodily processes |

Human

logic intermesh | – An organic open-ended dialogue between the human mind and computer based on the recursive feedback loops occurring during the meaning-making process |

Intertextuality | – Assembling texts from different sources in a manner that they ‘have a dialogue’ with each another |

Meme | – Artefacts created by remixing images found on the Internet to express jokes, satire or humour through portraying complex intertextuality |

Participatory culture | – A culture defined by active, formal or informal, engagement in producing new creative forms and sharing the creations through various forms of media |

Remix | – Cultural creative activity based on using pre-existing materials to create something new as desired by any creator-from amateurs to professionals |

Vidding | – Video remix often created to make individual statement by juxtaposing familiar video elements |

5.8 DOING

KNOWING: The Ripples Pedagogy in Practice

KNOWING: The Ripples Pedagogy in Practice

5.8.1 Learning Task Four: The Unity of the Mind and the World

Where does the mind stop and the rest of the world begin? Much of current thinking about human cognition seems to have neglected that the way we think is the property of a hybrid assemblage of brains, bodies, and things. (Malafouris 2013, p. 2)

- 1.

Read the quote above from the work of Dr Lambros Malafouris

In this unit of work, we will attempt to test Malafouris’ proposition about our process of thinking as a cooperative unity of brains, bodies and things.

To this end, we will investigate the extension of the mind through the relationships among brain, body and things within an abstracted space in the flow of our experience.

For example, let us isolate the most personal place of our existence—your bedroom, a studio or other space where you work if you do not feel comfortable depicting your bedroom.

- (a)

Create a detailed visual representation of the room. Use the technique of your choice. If you are depicting a working studio, include the space around your desk. You do not need to measure the parameters of the room or distances between the objects. This is a difference between the two investigative approaches described by Lévi-Strauss in this chapter. They are the work of an engineer and a bricoleur. For the engineer, the measurements of the room, distances between the pieces of furniture are of fundamental importance to determine the usability and ergonomics of the space, but the content is of less significance. For a bricoleur, however, using Lévi-Strauss’ definition, everything can be ‘an operator’, or ‘interlocutor’ in linking the flow of feelings, information and functions between mind, body and things. Borrowing from Lévi-Strauss, by examining objects, the bricoleur ‘is looking for messages’.

Additionally, when drawing the map, bear in mind one of the main principles of bricology, that is that the bricoleur operates in a DIY style. He/she is an amateur, not a skilful professional. A scratch on the wall could be a critical interlocutor, so you must invent a way of depicting it in your two-dimensional representation. Draw your map by Sherlock Homes’ principle: ‘I am glad of all the details … whether they seem to you to be relevant or not’ (Doyle 2002, p. 270). Use colour pencils to do a colour coding. Draw the pattern of the bed cover, the rug beside your bed, elements of decor and so on.

- (b)

Take a photo of the map with your mobile phone. Create a new desktop or graphic document. Title the project Entangled. The meaning of the title connotes the investigation of the synergy between your mind, your body and things around you as if they are intertwined with each other. Place the photo of the map on the first page of the document. Size it down so that you have some space at the side of the page for approximately three hundred words of text.

Are there any sounds that you believe are characteristic to your room, such as street noises, music that you usually play, or other background sounds? Audio record them and import them to your digital page.

Is there a window in your room that you like to look through, a door that leads somewhere else? Take photos of them and place them on the map. Ask someone to take a photo of you sitting on a chair, lying on a bed, doing your work or just standing. Incorporate your figure according to the affordances of the software used to create the visual.

In ‘reading’ and ‘writing’ your room, use cinematic writing (draw, make a diagram, take photo, sing a song, make sounds, etc.), and think about such things as:

what are the things in your room that are invisible to you most of the time, that exist only as a medium for other things to be situated within?

What are the things that create a bundle of presence? What is their configuration in the given space? How does your body respond to them? How do they make you feel?

What are the things that are accidental or temporary, serving only functional purposes?

Does your room make you feel in any way claustrophobic or too exposed? Why?

What are the things (beside your computer, mobile or any other digital devices) that make you feel that the room is connected with the world outside and why?

- (a)

- 2.

Present your bricolage to the people in your discussion group.

- (a)

Document the feedback you received from your peers and insights you gained from discussing their work in your bricolage.

- (b)

Experiment with the background on the second page and the effects of the map placed on it. Look for cross-modal effects to express the overtonal subtext of the room through colours, surface texture of the surfaces, patterns, hues, sounds or video fragments.

- (c)

Think about the things that you exhibit in your room on purpose and why. Take additional photos, place them in the bricolage and make an interactive connection to them—a hint, an explanation and so on. Audio-record your verbal explanation of why you want one of these things to be seen. Insert your audio-recording in the page.

- (d)

Think about the things that are placed away from view and why. Make additional photos of opened drawers or cupboards. Add interactive effects such as opening the drawers or cupboards, or drawn lines, such as an X-ray, symbols, written signs and so on. Explain in cinematic writing why you need to keep these things hidden. Where does the idea of keeping them away come from? Examine it closely. What are your points in supporting or objecting to it?

- (e)

Present the second page of your bricolage to the people in your discussion group. Document the results of the discussion.

- (a)

- 3.

For the third page, take a photograph of your personal affinity space.

Lately, affinity space has been widely recognised as a term referring to spaces where an informal community learning takes place (Gee 2017, p. 123). In the context of cinematic bricolage, the term is used in the direct meaning of the word affinity—natural liking. A personal affinity space is where you feel safe and with which you have a deep association. This can be any natural or man-made space.

- (a)

After you have taken a photo of such a place, position it in your bricolage. Audio-record sounds from this place. Import them into the page. Are there some movements that you can incorporate into your bricolage? For example, a bird flying across the page.

- (b)

Take a photo of the piece of furniture you consider to be central in the room you are working on and incorporate it into the photo of your affinity space. It can be something like a meadow in the forest with your bed on it.

With technology’s rapid developments, the creation of this kind of simulation within your current bedroom could be well possible in the near future. What other items from your room will you need in your affinity space? Take photos, clear-cut the objects and place them in the image of your ‘affinity space’. Is there a thing that you are very fond of and would like to have with you in your new setting? Explain this thing in non-linguistic modalities: sound, the feel of material it is made of, colour, or movement. If you feel that you need to use words, however, to label some parts or to better assemble your composition, use the words.

- (c)

How do you feel in your ‘new setting’? If you had to live in a place like this in reality, how would you feel? Discuss it with your peers. Discuss two possibilities: if it was a naturally organised space and if it was virtually simulated. What would be the difference in how you felt and what would be the consequent modifications of the space?

- (d)

Add a new page to your bricolage. Copy/paste the composition you have created on page three to page four. Make the modifications you think should be done to the space by drawing the elements, adding photographs and so on.

- (e)

Describe how different the space you have created is from the space that you are occupying now. Reflect on and explain why you have made those modifications.

- (f)

Write a three hundred word analysis of your observations of how your conceptual thinking was influenced by bodily requirements and dependence on things.

- (a)