9.1 Digital Tools ‘at Hand’

Of all the digital tools people use in their daily lives in our contemporary society, mobile phones are perhaps the most common. They are, in McLuhan’s (1964) sense, extensions of our physical bodies and ‘our central nervous system itself in a global embrace, abolishing both space and time as far as our planet is concerned’ (p. 16).

It is difficult to find a person at any time of the day who is not holding his/her mobile phone in their hand or keeping it in a pocket, purse, or briefcase, or having it lying nearby on a table or desk. Burgess (2012) considers the mobile phone as ‘a moment in the history of cultural technologies’ (p. 28). She further observes that the mobile phone ‘moment’ ‘invited us, as users, to be repositioned in relation to the technologies we integrate into our everyday lives’ (p. 29). This repositioning is concerned with how we see ourselves situated in the world, not only in terms of space but also how we feel about our enmeshment into the social web of relations.

A mobile phone has become a rich database of individual’s contacts, records of personal interests and engagements, notebooks, libraries of favourite music, photo-albums, video and book collections. In a nutshell, it is an elaborate blueprint of the user’s identity. As Ripples pedagogy promotes learning towards self-design with the application of digital media, the mobile phone becomes a device of exceptional value. The data generated with this versatile device is unique, first-hand material drawn from the knower’s real-life observations and experiences.

In elaborating on its value, as Chris Chesher (2012) asserts, the mobile phone ‘became a self-contained simple mobile imaging apparatus, constantly at hand and largely self-contained’ (p. 106). As well as Jean Burgess also observes the mobile phone’s ‘extreme usability—where a technology affords easy access to a pre-determined set of simple operations, often via intuitive, “friendly” interfaces’ (p. 30). These essential features—that take the form of a self-identity data-archive, are self-contained and constantly at hand, with extreme usability—make the mobile phone an indispensable device in generating a personal database for learning. For this reason, the application of mobile phones as well as tablets for generating data from daily life becomes a rudimentary requirement in Ripples learning.

Stationary equipment, computers, Wacom tablets, scanners, printers, and now, affordable and accessible 3-D printers are used in Ripples learning to convert the gathered data into applicable formats, generate images, edit video and audio files, write and assemble multimodal documents, and construct installations and 3-D models. In terms of software, I see stunning potential in the use of Adobe Creative Cloud (ACC) that provides their clients with creative suits of updated software and technical support. However, ACC is oriented towards creative professionals, and both the software and their cross-navigation appears to be rather sophisticated for application in DIY educational projects. Nevertheless, I emphasise the potential of the ACC for developing something like the Knowledge Cloud, a suitable system for students to gather, organise, analyse collected data and to assemble learning outcomes in EPUB, website or 3-D formats.

This chapter focuses on examining and demonstrating the instrumentality of the application of digital media in the Ripples model. At the moment, ‘the market-leading software’ for writing is Microsoft Word (MW). This software contains many features of desktop publishing. Although the distinctions between word processing and desktop publishing software appear to be blurring, the main difference, which is the organisation of the elements within the working area, remains fundamentally dissimilar. The difference is that MW compositional space is confined within the linearity of the continuous text box, whereas Adobe InDesign (ID) assembling features are flexible. In MW, the elements can be moved only along or within the text box. In ID, the elements, including animations and videos, can be moved around, re-sized, modified independently from each other, distributed on different layers, overlapped, have various effects added to them and, in addition, there is an option for the adjustments made within the timeline. The letters can be converted into shapes and manipulated as objects separately from other text boxes.

These working principles make ID and other software in ACC ontologically congruent with the circularity, deep remixability and diversity of cinematic bricolage methodology that is suggested by the Ripples model. However, as mentioned above, ID is a professional publishing software heavily equipped with the features and operations essential to skilful designers and artists and, for this reason, it is unsuitable for a wide-range of educational activities. The development of a digital system that is conducive to a DIY user in developing their knowledge-production skills in alliance with their interests and abilities becomes a matter of urgent concern for modern education.

9.2 Building Blocks of Digital Media

linearity with simultaneity, velocity, and multiplicity of sequences of events, suggesting one of the core subjects in the twenties century avant-garde: the extension of the human sensory apparatus by means of aleatoric and technologically enhanced artistic procedures in search of new areas of experiences, in which the borders between the so-called inner-world and outer-world would eventually dissolve. (loc. 2343)

Sonvilla-Weiss sees such a ‘merger of inner and outer worlds’ being manifested in the collages of Max Ernst, with which he suggested unexpected meetings of imagination and reality represented by incongruous clashes of biological forms with technological elements.

Comte de Lautréamont in 1920 attempted to describe beauty by throwing the reader’s mind into a state of total confusion, forcing him/her to recognise harmony, for example, in a visual ensemble of an umbrella being placed together with a sewing machine on a dissecting table.

In his article Avant-garde as Software, Manovich (2002b) argues: ‘What was a radical aesthetic vision in the 1920s had become standard computer technology by the 1990s’ (p. 7). Manovich also draws attention to the work of George Seuraut and his experimental painting techniques such as chromoluminarism —combining colours optically instead of physically mixing pigments, which can be linked to CMYK —the colour mode of four inks used in printing (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and Black)—and RGB —the light (screen)colour mode consisting of Red, Green and Blue. Seuraut’s pointillism, or painting with dots, can be recognised as future lay-outs of CMYK or RGB pixels in construction of a digital image.

Another artist, Vasily Kandinsky, attempted to convey a complex psychological message through simplistic forms. Manovich connects this to such computer techniques as visual atomism. He recognises the re-appearance of an atomistic approach in images mediated by computer media where simple elements charged with emotional meaning became the basis of visual communication (p. 4).

Likewise, avant-garde approaches such as montage and collage can be considered the precursors of cut and paste methods and the layered structures of image generation and the remix technique. Manovich maintains that digital graphic design, advertising and commercial visual communications trace their roots to the avant-garde movement. He states, ‘the avant-garde becomes software’ (p. 11). In the next five sections I draw on Manovich’s analysis of the digital media building blocks that together serve as a framework for a transition from ‘avant-garde to software’.

9.2.1 Numerical Representation

Lev Manovich identifies (2002a) five principles of digital media that shape the logic with which digital objects and their behaviours are constructed, manipulated and assembled: numerical presentation , modularity, automation , variability and transcoding .

When numerical presentation is applied, analogue media is converted into discrete units of digital code and acquires a new system of semiotics. In Manovich’s (2002a) words, the new system ‘follows the logic of factory’ (p. 29); in other words, the data is first described by a standardised code and second, the units of the code can be separated and recomposed. This means the items of material data are either scanned or digitally photographed. Sounds and videos are digitally recorded. Graphics are constructed in such applications as Adobe Creative Cloud, Illustrator, Photoshop, Adobe Animate and InDesign. Hand drawings and sketches are scanned, and so on.

The digitised items–bricoles can be represented as separate files saved in appropriate formats compatible with the intended changes applied to other digital bricoles. As they are represented in numerical form, they are subjected to algorithmic manipulation. In general, the Ripples’ knower—with the exclusions of the tasks oriented to learning about computer algorithms—does not operate on this level. The bricoleur engages in an interplay between what is available in his/her repertoire. The bricoleur’s focus is directed to the discovery of the most congruent ways in using the affordances of digital media to think self-naturally about the meaning emerging through the process of representation. In other words, the bricoleur’s actions are directed towards maximising of the user experience of what is already made available for him/her within digital environments and in a particular software.

9.2.2 Automation

Automation is a principle of standard software operations. Certain algorithms assigned to certain operations allow the access and certain manipulation of media objects. Inside a given software environment, the media object can be manipulated only within the parameters of what it was codified to do. Although limited by programming, automation is the principle that makes human-computer interactions possible.

In relation to the projection of reality, images produced by means of automation are more accurate. In relation to reality, their shapes are modelled correctly, their tonal gradations are smooth and they can also be generated much faster than when drawing by hand.

Although, computer-generated images are visually effective, produced with less effort and in less time; they may miss the personal touch. The absence of individual interpretation often makes them rather flat and flavourless. When circles are precisely round, 3-D features immaculately articulated, and colour gradations flawlessly blended into each other, it is difficult to recognise the individual artistic quality or emotional value invested in the graphic. Therefore, the artistic tendencies of digital culture are oriented towards creating eclectic montages manifested through the deep remixability of heterogeneous methods and materials.

For classroom purposes, however, automation opens up new possibilities for the observations of the relational dependencies between objects and concepts. By freeing time and providing easy methods for image generation, even for a person with undeveloped drawing abilities, automation removes the hurdles of the representational task and enhances the delivery of educational material.

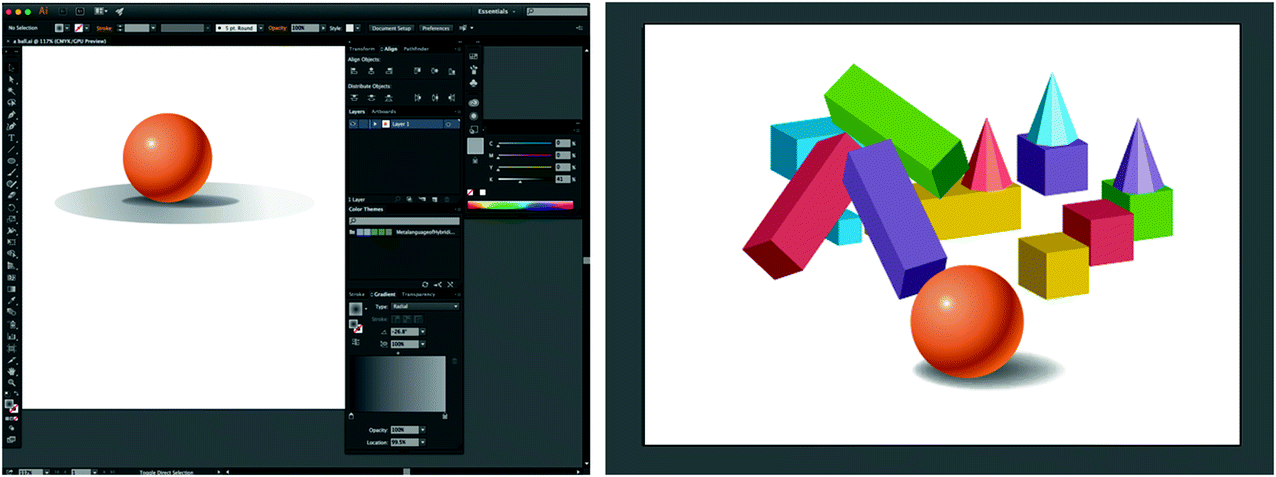

Examples of visual interactivity that the teacher can demonstrate using Adobe Illustrator when teaching about shapes

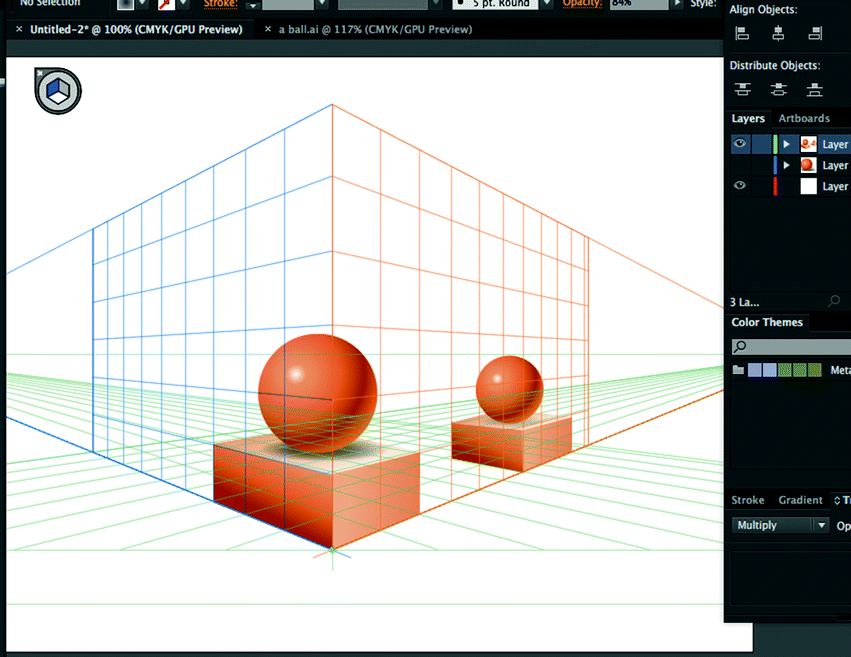

Example of visual interactivity that the teacher can demonstrate using Adobe Illustrator when teaching about perspective

Here, the teacher and students adopt a bricoleur ’s approach. They use the tools and media objects already available inside the representational software. It is advisable for the studio to have collections of pre-coded shapes, brushes, strokes, patterns, operations, effects and so on. The software is also needs to be conducive to the addition of new sets of personal data, generated within the application or photographed and imported into the virtual studio. By being digitised, the objects can be disjoined and their elements remixed in a DIY manner. As a software user, the bricoleur-knower forms his/her personal methods of exploration and acquires a sense of ownership of the newly emerging ideations.

Lévi Strauss (1962) writes: ‘The ‘bricoleur has no precise equivalent in English. He is a man who undertakes odd jobs and is a Jack of all trades or kind of professional do-it-yourself man’ (p. 17). In this light, automation allows both the teacher and the student to avoid the anxiety of having ‘no talent’ when creating representations in either visual, sound/musical or movement form. Easily achievable automatic representations ‘smooth’ the path to more sophisticated cognitive operations in the exploration of patterns of associations and constructions of new meaning.

Automation can also aptly serve metaphorical formations. A student can benefit from the easy remixing of digital objects between the associative and analytical domains. Such social concepts as transparency of management, saturation of phobias, racial differences, individualistic self-expression and contrasting opinions can be discussed by means of metaphorical logic and using automated software functions to manipulate shapes, colours, patterns, strokes, brushes, sounds, movements and combined effects. Such easy operations as remixing of representational elements and formats, facilitated by the automatic functions of digital media, promotes ‘individual customisation, rather than mass standardisation’ of teaching and learning (Manovich 2002a, p. 29).

no requirement for special professional skills or talent but working with DIY principle in generating basic representations;

friendly, manageable remixing among elements and modes in the application of metaphoric logic; and

accessible manipulation and remixing of elements and modes for personalised knowledge production.

9.2.3 Modularity

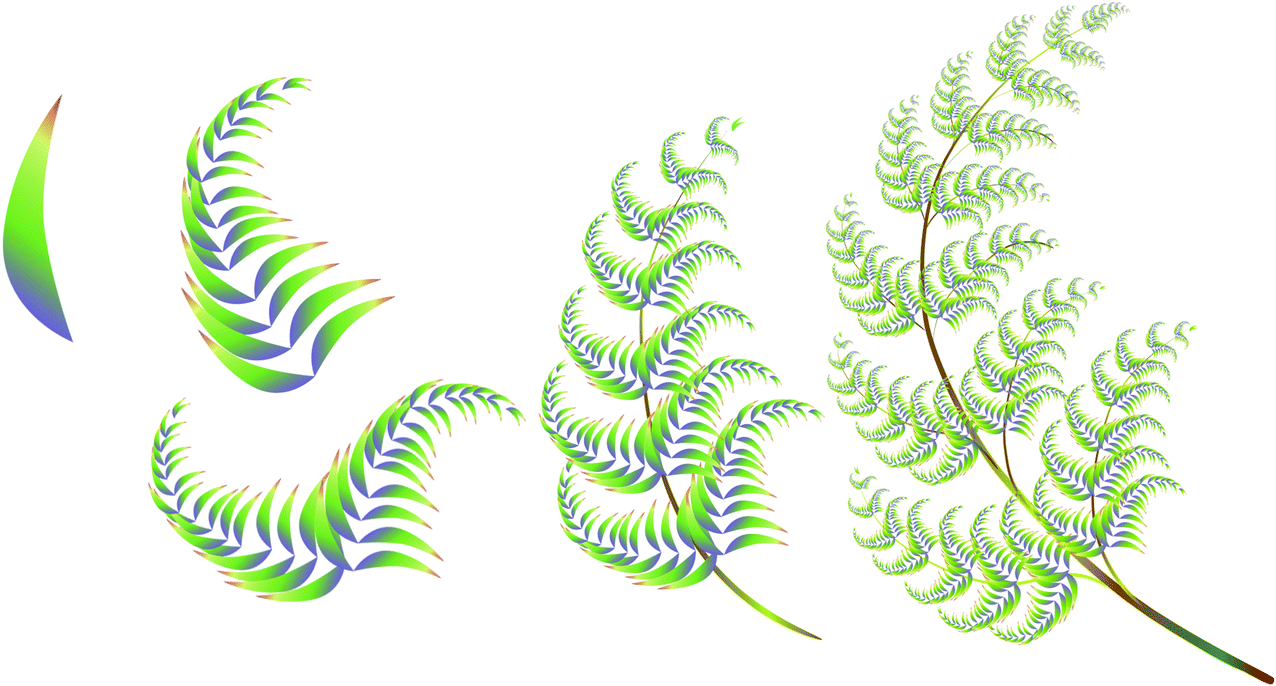

Modularity preserves the independence of digital objects and their compositions and allows to break them back into fragments at any stage of the production. Manovich called modularity a fragmental principle of digital media. This means that the production of digital novelty can be explained by the application of fractal modularity. This notion suggests a parallel between a creative recombinational approach, as discussed earlier, and self-similarities and irregularities in nature from the study of fractal geometry.

A new media object consists of independent parts, each of which consists of smaller independent parts, and so on, down to the level of the smallest ‘atoms’ – pixels, 3-D points, or text characters. (Manovich 2002a, loc. 860)

The illustration shows the development of the generation of a fern branch. The leaf-fractal was drawn with the Pen tool. By means of automation, it was then copy-pasted a number of times in a specific order with decreasing size and a slightly changed rotation, whereby it was turned into an image of a branch. The branch was copy-pasted into a pair of branches, and then copy-pasted again into a bigger branch. This could be done again and again but the initial object, the leaf, can always be selected and manipulated independently.

Fractal construction of a fern leaf using principle of modularity

9.2.4 Variability

Variability is realised by the interplay between numerical coding, automation and modularity. Variability is a digital-media mechanism by which endless reconstructions are realised. As mentioned, in contrast to old media objects, new media objects can be separated by their numerical presentations or fractal elements and remixed in new ways as often as required. As a cultural category, variability enables the user with a great deal of freedom in producing, manipulating and personalising media outcomes.

The result is the emergence of ‘new hybrid aesthetics that exist in endless variations but its basic principle is the same: juxtaposing previously distinct visual aesthetics of different media within the same image’ (Manovich 2013, loc. 4413). This is consistent not only with objects that are represented as images but also with objects represented as alphabetic signs, audio and various behavioural modes.

As Manovich proposes, the computer can therefore be seen as a meta-language platform: ‘the place where many cultural languages of the modern period come together and begin creating new hybrids’ (Manovich 2013, loc. 4413).

Manovich observes that in professional and cultural practices, people typically use a subset of resources that is appropriate for constructing ‘particular kinds of content and experiences’ (loc. 4837). Every such subset facilitates the realisation of techniques necessary for meeting a distinct performance. The groups of work that can be distinguished by exhibiting apparent patterns represent individual genres (loc. 4837). In this context, variability has an important role to play in establishing a subset of conventions and resources for the emerging genre of cinematic writing. Digitisation, automation and modularity catalyse assembling the variables and adjusting the components to reach a synthesis in representations between academic discipline, and socio-semiotic trends.

9.2.5 Transcoding

Transcoding means to translate something into another format (Manovich 2002a, p. 47). McLuhan (1964) defines the act of translation as a ‘spelling-out’ of forms of knowledge’. He conceptualises technology in general as nature translated into amplified and specialised forms (loc. 866). In the case of electric technology, however, he sees a difference. ‘All previous technologies were partial and fragmentary, and the electric is total and inclusive’ (loc. 877).

Talking about computers when they were in their infancy, McLuhan recognises their affordance of ‘getting in touch with every facet of being at once, like the brain itself’ (loc. 3548). The digital computer, McLuhan maintains, ‘points the way to an extension of the process of consciousness itself, on a world scale…’ (loc. 1158).

Discussing the transcoding category, Manovich (2002a) refers to the ‘revolutionary work’ (p. 47) of Marshall McLuhan and other theorists who began media studies in the 1950s–1960s. Following their example, he calls for a new stage of media study that will move from media to software theory. This initiative is a result of discussion about the transcoding category because of ‘the most substantial consequence of the computerisation of media’ (p. 45), which therefore has a global effect on culture at large. In other words, transcoding can be seen as a process of the all-inclusive translation of nature into digitised forms that causes the emergence of, borrowing from McLuhan (loc. 151), ‘new patterns of human association’.

Within the context of digital media, the ‘patterns of human associations’ with computers are seen as a media ecology that consists of two distinct layers. Manovich (2002a) defines these as the ‘cultural layer’ and the ‘computer layer’ (p. 45). According to the main principle of the ecology system, all elements that the system is composed of interact with each other towards maintaining the system’s equilibrium. Therefore, all elements are found to be under the influence of each other. The result of media ecology composite is, Manovich (2002a) states, ‘a new computer culture – a blend of human and computer meanings, of traditional ways in which human culture modelled the world and the computer’s own means of representing it’ (p. 46). In the act of being codified into a symbolic system of numerical presentation, old media becomes new media. Manovich observes that ‘new media may look like media, but this is only the surface’—underneath, ‘it is simply a computer data’ (p. 47). In this way, McLuhan’s prediction (1964) about ‘fashioning a total environment as if it were an artefact’ is coming one step closer to being fulfilled.

To become an artefact, the databases of a transcoded data must enter another dimension: that of human meaning and the way that meaning is expressed, or a sequential human logic, the narrative. Within the parameters of this dimension, the function of transcoding acquires a new nature. It is not just a dialogue between the elements within the ‘computer’s own cosmogony’ (p. 46) but also the emergence of new patterns resulting from the interactions between human logic and the affordances and limitations of digital media. These patterns make themselves evident by endorsing a greater complexity of configurations and favouring an aesthetic dimension to facilitating articulations and recognitions of their relationships.

In the emergent patterns of human

computer logic enmeshment, such operational affordances of digital media as transcoding, allows the user to address the complexity of the world, which is the central focus of the bricolage-oriented knowledge creation.

computer logic enmeshment, such operational affordances of digital media as transcoding, allows the user to address the complexity of the world, which is the central focus of the bricolage-oriented knowledge creation.

9.3 Perception Parallels, Software Layers and Reconnected Learning

the meaning … grows as we mark more differences, similarities, changes, and relations– that is, as we make finer discriminations within the ongoing flow of experience … Cognitive processing does not occur merely in a linear direction from core to shell structure. There are reentrant connections … (Johnson 2007, p. 102).

This is because normal perception naturally gravitates toward holistic integration, with all of the sensory streams able to receive some degree of mental representation at the same time. Holistic integration is a tangible quality of experience made possible by the parallel form of information structure emergent in the architecture of the brain’s sensory processing systems. (p. 67)

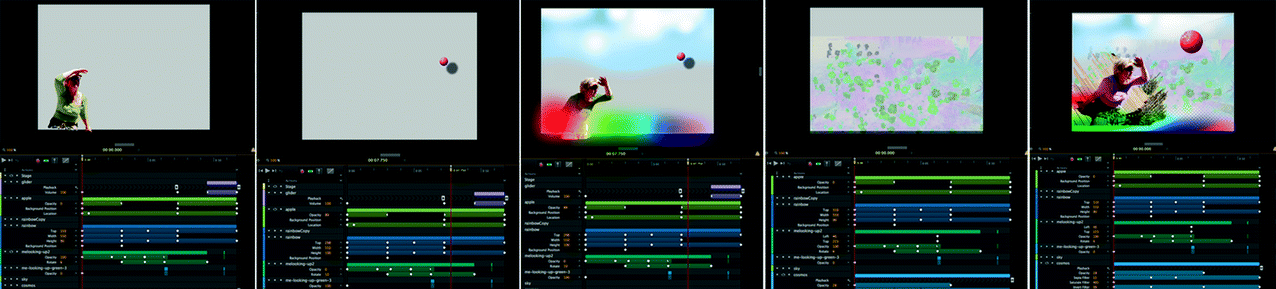

Unified projection of the production layers in Adobe Edge Animate

This is s demonstration of the Adobe Edge Animate layers. The work is done on each layer separately in a linear fashion, as the timeline below the screen-images show, but the working screen always shows what the whole composition looks like when the layers are merged together.

The Adobe Edge Animate item was then published and imported into Adobe InDesign. Again, although the layers acted as discrete components, together they have created one unified field for the experience.

Information can be maintained in parallel, the concepts formed from sensory data tend to be configural, that is, shaped into patterns that integrate the entire sensory surround. (p. 67)

We may not notice how a certain smell colours the quality of a time or place until an unexpected encounter at some future time brings back a vivid memory of a unique episode of personal history. (p. 66)

In the quote above, the term colour assumes the form of a verb to assign a quality to a smell, that in its turn, evokes certain experiences in specifying time and place. In other words, this can be a clue as to how ‘a finer discrimination within the ongoing flow of experience’, quoted earlier from Johnson, can be actualised. This indicates the mechanism of a metaphor being useful in employing modularity, variability and layered structures in the development of more inclusive systems of meaning-making.

In the Ripples methodology of knowing, a digital media user is not expected to be computer savvy. The generation of digital content is performed within a sphere of students’ existing competency, which is not limited to but is often outside working with algorithms and data structure. In the journey for knowledge, the knower is getting the most out of his/her present personal repertoire and external resources, reproducing from what already exists. Engaged in the dynamic interaction of reflecting on his/her thoughts and performance, as well as interacting with the surrounding world, he/she inevitably gains new skills and new understanding. Connecting natural and digital environments by means of privatised tools of knowledge-production and searching for ways of merging inner and outer worlds, the knower learns about, and forms new systems of communication with others and with the environment, thus building on and developing further his/her individual repertoire of the world’s interpretational techniques. The recursive feedback loops facilitate configurations of sensory data that becomes refined through interactions with a teacher, learning group, class or social media participants.

If we borrow Walter Benjamin’s (1935, [2012]) notion of ‘aura’ in relation to the uniqueness of embodied expressions, where he argues that ‘The whole province of genuineness is beyond technological (and of course not only technological) reproducibility’ (loc. 155), we can make an observation that has an important implication for education. Benjamin’s emphasis on the term technological indicates the accessibility to the representational resources and convenience of automated production. Put simply, having resources at hand and possessing an easy way to produce the right answers does not imply the authenticity of learning.

The major principles of authentic education are that learners should take a more active part in their learning, and that this learning should be closely and practically connected to their life experiences. Authentic education is more child-centered, focusing on internalised understanding rather than formal repetition of the ‘right’ answer. (p. 39)

Directing its philosophical principles away from repetition of the ‘right’ answer towards a child-centred learning process, the Ripples model assists in the development of skills in the use of digital media to amplify self-authenticity in learning. These approaches are facilitated by such principles of digital media as automation, modularity and variability. These categories provide the affordances with which accessible resources can be internalised and practically connected to students’ life experiences and not simply repeated and reproduced in accordance to ‘right’-expected representation. Engagement in dynamic ripplework establishes conditions conducive to the ‘collision of all stimuli’ (Eisenstein 1949), collision of incompatible matrices’ (Koestler 1989) and ‘collision of fragments and layers’ (Barbatsis 2005), as discussed earlier—where the term ‘collision’ was suggested as an essential feature in production of creativity. The digital content generated throughout the learning task grows from students’ genuine, i.e., personalised context, in which the aura, using Benjamin’s (1935) term, does not ‘shrink’ (loc. 178) because of technological production but becomes augmented.

Here, I adopt Marshall McLuhan’s (1964) terminology to say that the Ripples model catalyses the learning to be ‘spelled out into’ a new ‘form of knowledge’. McLuhan’s famous argument ‘the medium is the message’ implies that the medium shapes and controls ‘the scale and form of human association and action’ (loc. 168). It is through the ongoing circularity of interactions where the affordances of the medium are constantly modified by humans, that the message is altered in accordance with the modified medium.

9.4 Agency of Transcoding

The Ripples system of representation

meaning-making, with its notion of reconnection and application of cinematic bricolage, pushes knowing to a new conceptual terrain and advocates for theoretical modernisation. The representational content generated in cinematic bricolage is built on a methodology of active involvement through questioning and feedback looping while gradually making explicit what previously appeared obscure. Through the physical engagement in doing, the bricoleur brings to light the nature of knowing reflected in methods he/she enjoys to use and is good at. The act of representing which is achieved through the application of cinematic writing, is a process of transcoding

the essence of things and their relationships into a personalised multimodal system of expression.

Multicoding

is actualised through employing a layered system of production whereby narrative and database components become permeated into a series of unified projections.

meaning-making, with its notion of reconnection and application of cinematic bricolage, pushes knowing to a new conceptual terrain and advocates for theoretical modernisation. The representational content generated in cinematic bricolage is built on a methodology of active involvement through questioning and feedback looping while gradually making explicit what previously appeared obscure. Through the physical engagement in doing, the bricoleur brings to light the nature of knowing reflected in methods he/she enjoys to use and is good at. The act of representing which is achieved through the application of cinematic writing, is a process of transcoding

the essence of things and their relationships into a personalised multimodal system of expression.

Multicoding

is actualised through employing a layered system of production whereby narrative and database components become permeated into a series of unified projections.

[…] the characteristics of an environmental medium are that it affords respiration or breathing; it permits locomotion; it can be filled with illumination so as to permit vision; it allows detection of vibrations and detection of diffusing emanation; it is homogeneous; and finally, it has an absolute axis of reference, up and down. (p. 17)

‘All these offerings of nature, these possibilities or opportunities,’ Gibson calls affordances, thus coining the term for what the environment offers the animal. As Joanna McGrenere and Wayne Ho (2000) explain, affordances are ‘an action possibility available in the environment to an individual’.

Earlier, the term affordances was defined within a context of representational digital media as its capacity, that is, what it offers to its user. From a perspective of human agency, we should add a new dimension to it. This comes from Donald A. Norman’s (2011) explanation of Gibson’s concept, where he states: ‘relationships between potential organisms and potential objects that exist in the real world whether or not anyone was aware of their presence’ (p. 228). To summarise this, the term affordances in the Ripples model, is seen as a potential capacity of digital media to influence the character and extend of the knowledge production. The knower who undertakes the Ripples approach to learning chooses affordances that are conducive to his/her learning goals, interests and abilities. The availability of these possibilities incites him/her to select and develop approaches that he/she would not have been able to implement without the use of digital media.

As much as the natural environment always existed for teaching and learning, digital environments opened new educational perspectives. Mobile digital media tools enabled the learner with agentic capacity to act by collecting data from his/her surrounding conditions. The Internet provided him/her with the multitude of resources and novel social interaction, surpassing distances, national borders and language barriers. Computers, printers, scanners and tablets assist the progress of data reconstruction and production, giving everyone an equal opportunity of becoming an author.

In these conditions, the more familiar a knower becomes with the affordances and limitations of new media and the environments, the more modernisation he/she applies to the ways of knowing. As a result, the knower re-designs the modes of thinking, methods of communicating with the surrounding world, tools of production, and ultimately, ways of being. In other words, representing

meaning-making as an ever-evolving projection of the human

meaning-making as an ever-evolving projection of the human

technology logic circularity, thranscodes human thoughts and experiences into material forms resulting in new technological possibilities. Every novel form of this projection is an expanding ripple that amplifies human capacity into technically transcoded data. Every ripple is a new segment in a human/technology entanglement. The more there are knots, the tighter is the dependence.

technology logic circularity, thranscodes human thoughts and experiences into material forms resulting in new technological possibilities. Every novel form of this projection is an expanding ripple that amplifies human capacity into technically transcoded data. Every ripple is a new segment in a human/technology entanglement. The more there are knots, the tighter is the dependence.

From this perspective, the Ripples methodology is an approach to learning that promotes the binary re-connectivity between the given and the constructed manifested in such circularities as: natural

digital; conceptual

digital; conceptual

material; subjective

material; subjective

socially ‘common-sensed’ and so on. A vivid example of how the boundary between an organic nervous system and digitised categories fades away can be observed through the layered system of creative production, where the ripples of the responses to the mind-cinema blend with the ripples of the responses to the database elements in a continuous whirl throughout the process. As discussed earlier, the circularity that makes this process possible consists of a binary code: human intentionality

socially ‘common-sensed’ and so on. A vivid example of how the boundary between an organic nervous system and digitised categories fades away can be observed through the layered system of creative production, where the ripples of the responses to the mind-cinema blend with the ripples of the responses to the database elements in a continuous whirl throughout the process. As discussed earlier, the circularity that makes this process possible consists of a binary code: human intentionality

digital media affordances. If we imagine these two categories start unpacking themselves like swelling ripples emerging from two boxes, we can distinguish, for example, ideas, desires, beliefs, memories, sensory-motor associations, knowing, feelings, and experiencing among the organic category, merging together with photos, sounds, generated graphics, applied effects, and algorithms of the manufactured category. The ripples blend, affecting and altering each other, and forging new ripples. In separation, neither of these two categories has the capacity for creating a material output, but only when two of them, are rippled through, will they inform, influence each other and give birth to a desired result.

digital media affordances. If we imagine these two categories start unpacking themselves like swelling ripples emerging from two boxes, we can distinguish, for example, ideas, desires, beliefs, memories, sensory-motor associations, knowing, feelings, and experiencing among the organic category, merging together with photos, sounds, generated graphics, applied effects, and algorithms of the manufactured category. The ripples blend, affecting and altering each other, and forging new ripples. In separation, neither of these two categories has the capacity for creating a material output, but only when two of them, are rippled through, will they inform, influence each other and give birth to a desired result.

In this sense, every binary concept described in this text and considered for the Ripples methodology loses its meaning if broken apart. There cannot be a collective without an individual, culture without nature, or production without the dynamic union of the material and immaterial. With regard to the above, the Ripples model rejects the notion of the neutrality of the knower and draws attention to the significance of human subjectivity and individual agency being entangled and reconnected with the agency of the environment, tools of production and social others.

9.5 Convergent Points

This chapter has sketched out the instrumental features of digital media that have marshalled such cultural practice as deep remixability. Manovich draws a parallel between avant-garde art and digital media principles, arguing for a direct connection in translating dot-painting into computer pixels as well as manual artistic approaches such as collage and montage into computer algorithms such as cut and paste. Automation, digitisation and modularity allow media objects to be spelled out into digital configurations with the potential to be broken into independent modules. Here, we find a strong link to creative recombinational practices, which is amplified by the translation of the media objects into a common system of digital codes. Given that, what was incompatible for re-combinations before being converted into digital coding becomes compatible for the varieties of hybridisation. Using modules of media objects allows the achievement of creative outcomes, catalysed by individual’s curiosity and subjectivity are accommodated in the process. Fractal geometry, in this context, provides insight into gaining a creative result through the application of irregular techniques in making meaning and breaking with a unified conformity.

Within the digital realm, coding systems are packaged into various formats, allowing the application of more sophisticated and specialised behaviours to media objects. Accordingly, transcoding operates between the formats to align the compatibility of various coding systems. Again, it affects creative practices on a cultural level as the creative and digital dimensions have to adjust to each other in a functional manner.

computer

logic enmeshment within creative and representational processes. In this chapter, it extends to the discussion about blurring the boundaries between human cognition and digital media affordances and leads to an issue of human agency’s essentiality where technology riddles through human, organic and natural dimensions.

computer

logic enmeshment within creative and representational processes. In this chapter, it extends to the discussion about blurring the boundaries between human cognition and digital media affordances and leads to an issue of human agency’s essentiality where technology riddles through human, organic and natural dimensions.Key Terms | |

|---|---|

Aleatoric | – Choices in art characterised by randomness or chance |

Automation | – Access and manipulation of a media object by means of assigned algorithms |

Avant-garde aesthetic | – Aesthetics of breaking from traditional and accepted, experimental |

Chromoluminarism | – Optical (screen) approach in combining colours instead of physically mixing pigments |

CMYK | – Colour mode of four inks used in printing: Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and Black |

Cut and paste | – In digital production, can be considered as an analogous technique to hand-crafted montages and collages |

Modularity | – Media object existence in smaller modules (fractals) that can be manipulated independently |

Multicoding | – Embodiment of meaning with writing, images, sounds and movements (cinematic writing) |

Numerical representation | – Conversion of analogue objects into discrete units of digital code |

Pointillism | – Painting with dots |

RGB | – Light (screen) colour mode consisting of: Red, Green and Blue |

Transcoding | – Translating media objects into different formats |

Variability | – Endless possibility to reconstruct media objects by remixing their modules |

9.6 DOING

KNOWING: The Ripples Pedagogy in Practice

KNOWING: The Ripples Pedagogy in Practice

9.6.1 Learning Task Eight: Human

Machine Enmeshment

Machine Enmeshment

‘Our machines are disturbingly lively, and we ourselves frighteningly inert […]

Technology is not neutral. We’re inside of what we make, and it’s inside of us. We’re living in a world of connections — and it matters which ones get made and unmade. (Haraway 2016)

Testing the theory—doing, observing and making your own meaning

- 1.

Start your digital journal and write approximately 200 words of your personal response to these quotes.

- 2.

Construct a question from these quotes that you would like to examine more closely. For example: Are machines living things? Who/what is a cyborg?

- 3.

Look for the articles on the internet; ask the people on your social media sites; talk with or interview your family members, friends, acquaintances: what do they think about it?

- 4.

As you gather factual information, look for multimodal data as well. Gather images, audio and motion ideas. Insert the bricoles into your digital file in a meaningful way that reflects your reasoning.

- 5.

Create a cinematic bricolage, assembling the data and writing with images, sounds and movements to represent your ideas in a final unified form. Use clear cut and paste techniques to assemble a multicoded collage for your construct. Annotate it in a way that the text, cuts, animated and video fragments constitute a gestalt assemblage conveying a clear message.

- 6.

Reflect on how your initial opinion has changed or altered due to:

- a)

Gathering more information about the topic;

- b)

Collecting other people’s opinions; and

- c)

Constructing a representational composition.

- a)

- 7.

Write approximately 200 words of your reflection.