I

The following morning I might have dreamed it all. It seemed impossible that anyone should have the audacity and the means to enter our house by the front door while we lay sleeping within. I might have considered the episode as part of a dream but for the fact that my nightmares never take such a clear and reasonable form. Also, there were still the remains of the shattered tumbler lying about the mahogany table.

I got up as soon as daylight was hard and cold enough to make the house look prosaic and not the background for moments of terror. Armed with a brush and pan, I went into the lounge-room without hesitation. Much as I wanted to confide in John about our prowler, I did not want to be asked any awkward questions. Just what I was doing around the house at that hour and why had I not roused him? The shattered glass had to be removed at once. Apart from the risk of Tony cutting himself, Tony’s curious father might wonder how it came to be broken.

I swept up the pieces and then opened the windows for clean, fresh air. John might feel the same instinct about a stranger in a room as I did. I had no qualms of conscience in suppressing the facts of my nocturnal adventure, although I was certain it belonged to some part of the mystery which permeated Holland Hall. John was quite capable of unravelling that mystery without any assistance from me.

I paused outside the lounge-room, brush and pan in one hand. Then I went along to the front door. I opened it slowly, watching the lock under my hand. As the draught swept down the passage the kitchen door banged in the distance. I shut it, then re-opened it again. I knew how the intruder had entered—through the front door.

By pressing a tiny lever on the lock it could be drawn back to stay, even while the ordinary latch fell into position. Once that was accomplished, entering the house was merely a matter of turning the door handle. The adjustment must have been made the previous evening. Any earlier and John or I would have detected it when using our latch keys.

The intruder was a matter of an alternative—either Ursula Mulqueen or Braithwaite the solicitor. Had I known last night that it was one of them, I would not have been so frightened. That was the mistake I continually made; not being afraid of anyone I knew. If I had recognized the murderer as an acquaintance, my feelings would probably have been the same.

It was one thing identifying the prowler but quite another to work out what they wanted so urgently from John’s file that made it necessary to take such a risk. Whatever it was, there was no doubt the venture had been unsuccessful. The time between my departure from the lounge-room and the falling tumbler was not enough to have covered an entrance, search, discovery and flight.

My eyes fell on the old-fashioned bolt and chain hanging loosely half-way down the jamb. Hitherto I had not bothered to use it when John was home. I smiled grimly to myself. There would be no repetition of last night’s episode. The Dower was my house and I intended to keep it inviolate.

When John was in the house things seemed much the same as usual. But I noticed a difference when he left for town to interrogate Ernest Mulqueen. Not even Tony’s scamperings up and down the passage banished that nasty feeling you get after your home has been broken into. I stood it until after lunch, when Tony went down for a nap. Then the house took on a deathly quiet, the same as I had crept through in the chill early hours.

I could not walk out of the place and leave Tony. Certainly there was the radio with which to infuse some atmosphere of unconcern through the house, but that was in the lounge-room. I felt quite incapable of sitting there after the events of the previous night. I wandered around the house waiting for Tony to finish his sleep. The perverse child seemed to be taking longer than usual. Most of the time I spent in the bedroom, pottering around and tidying drawers. I could sense John’s presence more keenly there than in any other room. Last night it had seemed like a haven. Once I went into the study with some wild idea of calling the Hall and trying to trick Ursula into giving herself away. I stopped myself in time. The person who broke the tumbler may have been Alan Braithwaite.

At last Tony woke up, quite unconcerned with the moments of distress I had put in while he slept peacefully. I bundled him into a coat and muffler to take him out for a walk.

“Under your own steam today, my son,” I said firmly. “It will take longer, but that is the idea. I don’t want to get back until it’s time for Daddy to be home. I’ll only get the jitters again.”

He climbed hopefully into the pusher as I searched for a harness to guide his steps. I shook my head. He got out with a loud sigh.

We wandered down the road towards the village. I had no set plan for the excursion, when my eye fell on the golf course at the right of the road. I remembered the ball I had lost on the day of James Holland’s murder. There wasn’t a chance of finding it, but it gave me an objective.

I lifted Tony over the fence and then got through myself. The long strap fastened to the harness was twitched from my grasp as Tony ran off down the second fairway. I cast an anxious look around, but no one was playing.

Presently he stopped and turned, waiting for me to catch up. I knew better than to hurry. It would only set him off again. As I proceeded at the same pace, he squatted down on the grass, bending over something interestedly. I made a sudden spurt and put my foot firmly on the trailing lead.

Tony did not seem to mind losing his stolen freedom. He stood upright with the object of his interest grasped tightly in one hand.

“Show,” I commanded, remembering other souvenirs. Against some protest I prised open his small fist.

“Good Heavens!” I said with mild surprise. “Maybe there’s a chance of finding that ball of mine if you can pick up a thing like this.” It was a baby’s dummy.

“What an extraordinary thing to find on a golf course,” I remarked, not recollecting that I had thrown it there myself. “Come along, fellah. We’ll make for the eighteenth. You can try out your sharp eyes there.”

I tried to persuade Tony to throw the dummy away, but he put it carefully into a pocket.

We cut across the fairways. Once or twice I had to lift Tony across a narrow creek. Luckily it was dry, as I slipped and half fell, much to the child’s amusement. We climbed up the slope of the seventeenth fairway. Ames was mowing the green. I thought it advisable to explain my presence on the course minus clubs and plus child. Also, I was unsure of my position. The open invitation to use the course may have ceased now with Mr Holland’s decease.

Ames was playing his cheery open-air role that day, conformable to the links. He was in an ideal setting. I stood off the green looking up to where he sat in the saddle of the machine, the sun on his handsome face. He listened to my explanations and refrained from saying immediately that I had not a hope in Hades of finding the ball. He spoke intelligently to Tony, who stared back with his eyes and mouth wide open, and finally rounded off the conversation smoothly by commenting on the dryness of the season and general drought conditions.

I made a half-hearted search for the ball, beating around the scrub with a stick. Tony followed suit. It was a new sort of game to him. After stopping his weapon on the shin for the third occasion, I considered it time to close the search. The fruit of my labours consisted of a very old ball indecently denuded of its outer covering. I was putting this in Tony’s pocket when a hail came from the tee. We hurriedly withdrew into the shelter of the trees and waited for a female golfer to drive off. She might have saved her breath, as the ball trickled to rest a hundred yards from where we had stood. When I saw that the female golfer was Daisy Potts-Power, I hastily worked out a plan of retreat to avoid meeting her. She had not recognized us and I had no desire to be caught again. Or hadn’t I? A notion came to me suddenly. Maybe Daisy would be useful. I waited until she took a number three to a low-lying ball. It came straight across the course to the rough without gaining the slightest ground towards the green. I marked its fall with my eye and strolled over to wait for her.

Daisy entered among the trees with bent head and eyes on the ground.

“Here!” I called, giving the ball a nudge with my shoe to send it onto a tuft of grass. It was a sure bet that she would hit a tree getting out, but I had made the lie a bit easier.

“Fancy seeing you here!” Daisy cried, with a wide delighted smile. She spoke as though our last place of meeting had been the other side of the globe. “Are you not playing? But of course not. How foolish of me.”

“This fellow impedes my freedom a little. I can’t haul him around the links.”

“So you are out for a walk together instead,” Daisy said in a sentimental voice. “What grand company he is for you! You must be great pals.”

I glanced about for Tony. He was off the lead again and I did not want him to stray. Actually he was standing immediately behind me, staring at Daisy. The beastly dummy he had found was in his mouth. I pulled it out, uncorking a long continuous sound of protest.

“Disgusting child!”

I wanted to throw the dummy away but the howl rose to such a crescendo that, with a strong warning, I replaced it in Tony’s pocket.

“How quaint of him!” Daisy said. “I noticed he had it in his mouth but I did not like to make any comment.”

I said in a firm voice: “No child of mine ever has nor ever will have a dummy. Your ball is here right at my feet. What are you going to use?”

She chose a number eight at random, buffeting two trees and pulling down a shower of leaves around us. After the confetti had blown away, I saw that her ball, by some marvellous chance, had just made the edge of the fairway. We strolled towards it together.

“I suppose,” I said tentatively, working on my notion, “that your mother is having her afternoon nap.” The slightest encouragement made Daisy loquacious. That was why few people gave it.

“I left her tucked up snugly in her chair in the garden. She likes to see people passing, you know. Mother’s really marvellous the way she puts up with her suffering. Her patience makes me feel my life is really worthwhile, devoting it to her. She may drop off for a doze if she becomes easy. If only people realized how remarkable she is.”

This disjointed speech was meant to convey two things: Firstly, that Daisy held the upper hand over her mother. Also, that she could have done something with her life had she so desired. From my impression of mother and daughter together, neither was convincing.

“If she likes to watch people going by,” I said, “she must like visitors. I’ll take Tony down to bring some brightness into her life.”

Daisy was inordinately pleased. “Would you really? That would be nice of you. I would come back with you, but I want to see Ames. He promised to show me some strokes. I do think he is an awfully nice man, don’t you? A real gentleman.”

“Rather,” I agreed, thankful that she thought so. “I’d hate you to miss a lesson.”

She laughed self-consciously. “I suppose you consider my game needs it.”

There wasn’t much I could say to that. Daisy was one of those players who would never learn golf. She was like those who lack card-sense. Either it is in you or it is not. The same with golf. I waved her on to the green, full of admiration for Ames, who preserved the role of a real gentleman when tutoring Daisy in golf. The lesson would keep her occupied until I learned from Mrs Potts-Power what I wanted to know.

II

The first information I gleaned was not from the old woman, but of her. The wheelchair was certainly in a secluded corner of the garden, but there was no mountainous, heavy-eyed occupant tucked cosily up therein.

So Connie Bellamy was right. I was not surprised. Rather I was embarrassed for the old woman’s sake. It is not pleasant to be taken in deception. From the low open windows at the front of the house came the sounds of the Viennese waltz to which Mrs Potts-Power was so addicted. I was beginning to hate Strauss. He was associated forever in my mind with that dreadful dinner at Holland Hall.

The garden path passed directly alongside the windows. I could not resist glancing in. Mrs Potts-Power was there as I had guessed. She stared directly into my eyes. That basilisk gaze of hers held me for a moment.

She said calmly: “I wondered when you would come. You’ll find the front door open.”

There was something uncanny about the way she sat there waiting for me, and not at all put out of countenance. I refused to be intimidated, although a sense of nervousness was mine.

When I entered the room she repeated: “I have been expecting to see you. I knew you would come sooner or later. Sit down and don’t let that child fidget. I don’t like children.”

My maternal hackles rose. Mrs Potts-Power regarded me with malicious amusement. I sat down abruptly. If you want something from somebody you have to dance to her tune, even a Strauss waltz.

She passed over a box of chocolates and candy. I selected one for Tony.

Mrs Potts-Power said: “Put it straight into his mouth. I can’t abide sticky fingers.”

“You know,” I said pensively, “you remind me very much of the late Mr Holland. Were you related?”

“Both malignancy and benignity are prerogatives of old age,” retorted Mrs Potts-Power. “James Holland and I chose the former.”

“With so much in common,” I asked, “why did you quarrel with him?”

“You are a very inquisitive young woman,” she replied.

“So he said also. Since you recognize curiosity as part of my make-up, perhaps you will tell me how you come to be out of your wheelchair? Does Daisy know?”

She chuckled, a low wobbly sound from the depths of her large stomach.

“Quite likely she has guessed. But it suits her better to deceive herself. ‘Poor mother! So dependent on me.’ Does she talk like that to you?”

My expression must have indicated my disgust.

“Come, come, girl,” Mrs Potts-Power said sharply. “Don’t you agree she is better being deceived? She’s far happier. And I like being waited upon and coddled. Sometimes she nearly drives me to distraction with her patience and submissiveness. As a matter of fact my heart is none too steady. It doesn’t justify a wheelchair, but it justifies me a little.”

“If you do nothing but sit around and eat, no wonder your heart is dicky,” I said.

“What have you come to see me about?” Mrs Potts-Power asked, heaving her bulk out of the chair after three attempts.

She moved the needle of the Panatrope to the edge of the disc.

“I thought you knew,” I retorted. “You said you’ve been expecting me.”

Mrs Potts-Power grinned. “I have a fair idea. But I wouldn’t like to give away more than you wanted.”

“Why did you quarrel with James Holland? Why were you, for the first time in years, suddenly invited to a dinner party at the Hall?”

She answered me without reticence. “I wanted Jim to marry Daisy. James didn’t like the idea. I think he was worried that my influence would be stronger than his. It would have been too,” she added reflectively. “I could hold out longer than James even when we were young. That’s why I didn’t marry him myself. It must have been a matter of ten years since I was at the Hall. I was there the other night at his invitation. I had won again.”

“Mr Holland won one round,” I pointed out. “His son married Yvonne.”

Mrs Potts-Power snorted. “Picked out for him just as James selected Olivia. Poor weak fools, the pair of them. James wanted women merely for breeding purposes. He realized women like me complicated matters. Olivia was the same as Yvonne. No relatives—no money. Just a young, foolish child who would submit herself mentally and physically to a stronger character.” She finished spitefully: “I daresay, had he thought of it, James would have got rid of them somehow, after they had served their purpose.”

“Quite the feudal lord,” I murmured. “Fate intervened in both cases, did it not?”

The old lady gave me a sharp glance. “What do you mean?”

“Before the idea occurred to Mr Holland to rid himself of his wife, she did it for him. In Yvonne’s case his plans were upset by his son’s untimely death. He was indifferent to her presence when she was no longer Jim’s wife.”

“Who has been talking to you? Elizabeth? How did you know about Olivia?”

“Mrs Mulqueen has told me nothing. But there is a photograph of Olivia Holland in her room. The picture caught my eye because it is turned to the wall. I defined it as a token of disgrace and punishment. Then I came across a letter. Strange how we women cannot resist writing farewell letters. It would have done your heart good to read it, if you considered Olivia a poor, weak fool.”

“I knew Olivia ran off, although James did not broadcast the fact. But you can’t go visiting relatives for years, especially when it is known you have none. Was there a man?” Mrs Potts-Power smacked her lips over this old scandal.

“No, I don’t think so. I am sorry to disappoint you. Although Olivia admitted in the letter that someone was helping her.”

Mrs Potts-Power stuffed caramels one after another into her mouth to make up for the disappointment. “I’d like to know who it was. Olivia hadn’t a friend in the world except those James had. And you wouldn’t call them exactly friends. Unless it was—” She broke off and turned her wicked eyes towards me.

I watched them, deeming it wiser not to urge her on. She was capable of leaving her remark uncompleted out of sheer cussedness. Her eyes narrowed to gleaming slits and widened again slowly. They looked at me blandly. Mrs Potts-Power had guessed at the identity of Olivia’s friend. But she wasn’t going to talk.

“Mrs Potts-Power,” I asked, “where is Olivia now?”

“She is dead,” Mrs Potts-Power replied promptly. “There was a death notice in the paper years ago. I remember reading it.”

“How many years?” I inquired, disappointed but persevering. “Who put the notice in? Not James Holland. Olivia had left him, remember.”

The blank look settled on Mrs Potts-Power’s face again. She was hiding some secret knowledge behind it. She became suddenly talkative.

“I don’t know how long ago it was. Jim was quite young at the time. My husband had just died. I had my own troubles. It did occur to me James might marry again, just to get someone to rear Jim. That was before that nurse came.”

“Where did Olivia Holland die?” I persisted.

Mrs Potts-Power thought, and presently recollected the name of the country town. It struck a familiar chord.

“Then there is no chance of Olivia being still alive, and better still, living somewhere in the vicinity of the Hall?” I watched the old woman’s face carefully.

“You have been reading too many mystery novels, Mrs Detective Matheson. Things don’t work out like that in real life.”

III

I left Mrs Potts-Power, my mind dazed with new discoveries and their confusing issues of possibilities and probabilities. She followed me out the front door and settled herself in the wheelchair, casting me a wicked look as she tucked the crocheted rug around her knees.

Tony’s steps were lagging as we climbed up the hill to High Street. I gave him an absent hand, automatically checking a stumble now and then. Two ideas were firmly fixed in my mind. Unfortunately both were difficult to develop. Olivia, the one to whom James Holland’s death was likely to prove a source of satisfaction and a fulfilment of revenge, was dead. She was out of this world, so far as a notice in the death column could prove. Could she have arranged her own death, or did Holland furnish the notice in order to stop scandalous whispers?

The second matter was the town from which Olivia’s death had been reported. That same town was recorded as the receiving station of the telegram Mr Holland sent to the Hall just before his murder. It was no strange coincidence but a hint of the Squire’s business during his last days. Had he, after all those years, suddenly decided to trace his erring wife’s steps and verify her death? Had he discovered something concerning her which caused him to bring together an ill-assorted table of dinner guests in order to make known such information?

There were so many questions to ask, so many answers that might serve. My brain whirled desperately. I was glad when a voice interrupted, calling my name.

Connie Bellamy came panting up the street. As she drew near I had a sudden sinking feeling. All thoughts of Holland Hall and its kindred complications vanished. I had asked the Bellamys to dine that night and I had forgotten all about the invitation!

Connie must have found me distrait as we walked along together. She held her chatter for a brief spell. I laughed at the look of deep understanding she directed on me. She had been asking about the case and imagined my mind was occupied with its intricacies. Whereas I was swiftly planning an impromptu dinner for my forgotten guests.

Passing through the village, I said: “I hope it won’t put you off, but you’ll have to watch me buying your dinner. I had rather a rotten night and didn’t feel up to preparing more than a grill and salad.”

Connie probably thought me a shocking housewife, but at least that was better than the truth. I came out of the butcher’s shop and found her talking to Daisy Potts-Power.

“Hullo,” I said. Daisy carried her golf bag slung over one shoulder with a professional air. “How did the lesson go?”

She was brighter than ever and excited. “Awfully well. I feel as though I might begin to play now. Ames was terribly patient with me.”

I frowned at the name. It would be a shocking thing if Daisy made a fool of herself in that way.

“Look,” she said. “Tony has that dummy in his mouth again. Isn’t he just the cutest thing?”

I swung round, catching a swift movement of Tony’s hand from his mouth to behind his back. He regarded me with a solemn eye which did not falter before my more-in-sorrow-than-in-anger look. I was not going to risk a scene right in the middle of the village, so I dragged Connie off. “How was Mother?” Daisy yelled after us, over two or three heads.

“Most enlightening!” I called back. “You might tell her I said so. You’ll find her in the garden all tucked up cosily in her chair.”

“Have you been calling on Mrs Potts-Power?” asked Connie curiously. “Did she ask you to?”

“Not exactly. It was more a matter of telepathy. I found her most entertaining, the old fraud.”

“Was she out of her wheelchair?”

“She was. And moving around as energetically as her bulk would allow. She’s only an invalid for Daisy’s sake. At least, so she says. I decline to comment on the situation.”

Connie lost some of her customary talkativeness as we drew near the Dower. I detected a certain nervousness in her manner and remembered the original purpose of this dinner party of mine. The cause of her distress was a matter to be discussed between her husband and mine. I thought it best not to interfere. In any case, it always took an age to explain a situation to Connie. She had been the slowest telephonist at Central.

I hurried Tony through his evening meal, slicing tomatoes and washing another lettuce at the same time. My head ached, a legacy from the broken night and the afternoon’s concentration on crime. The sudden readjustment of dinner arrangements and the prospect of the evening ahead did not improve it.

Connie proved herself quite competent when her aimless talk was stilled. Together we managed to prepare an adequate meal, fairly attractively served.

I gave Tony a quick face-and-hands sponge and put him into pyjamas. I did not feel equal to fitting in a bath amongst a dozen other things. I dumped him in his cot with a picture book to await John’s homecoming. He was confused at all the rush and bustle. It made him restless. Twice when I went in to see if he was all right he was out of bed and wandering around the nursery.

That would happen when I had guests! Usually Tony went straight off to sleep as soon as he was tucked down. But, in the perverse way children have, he chose to misbehave that night.

After dinner—the grill was slightly overdone—John drew Harold Bellamy into the study, closing the door behind him. Connie stared at it in a frightened way.

“There’s nothing to worry about,” I said briskly, “as long as he is quite frank. You see, John found out about Cruikshank’s little game himself. Come and help me with these dishes.”

Connie said, following me out: “There is a letter Harold wrote to Mr Holland. Oh, Maggie, I’m so scared.”

“Don’t be scared. The letter has already come to light. I’ve read it myself, so you can understand how little John thinks of it. Drat! Was that Tony again?”

It was, and the poor lamb must have been crying for some time. The conversation at dinner had prevented me from hearing him. I went into the nursery, switching on the light. He was lying on his side facing the wall, and crying softly in a way that made me feel a brute to neglect him for a couple of dinner guests. I felt even worse when I lifted him. He lay in my arms limply, not caring who it was. I felt his forehead and neck anxiously, but there was no fever. He looked a little pale to my super-critical gaze, but his small tongue was quite pink and healthy.

I tucked him up in his cot again, leaving the nursery door ajar and the light aglow in the passage. Connie had started the dishes with a vigour that spelled uneasiness.

“What is the trouble with Tony?” she asked absently.

I found an apron and tied it on. “Dunno. I never have understood children and I never will. If I do the drying we will be about equal. Or would you rather I washed now?”

“I don’t care. Are they still in the study?”

“Who? Oh, the men. I suppose so. I didn’t hear them come out. We’ll go back to the lounge-room after clearing up.”

Poor Connie! Just because her precious Harold had been misguided enough to write a letter concerning Cruikshank’s activities to the Squire, she seemed to believe her whole life was in jeopardy. However, this attitude was dispelled when we passed the study door on our way to the fire. A burst of hearty unrestrained masculine laughter nearly broke down the closed door.

I raised my brows at Connie. “Sounds like a serious conference. Dare we interrupt?”

Connie looked indignant. “To think that I have been nearly worrying myself sick! I do think it is too bad. Of course, I knew that there was really nothing to be frightened about, but—” Connie’s relief had unplugged her volubility again.

I put my head in the study door.

“We are just coming, Maggie,” John said hastily. “Sorry we have been so long.”

“If the fire has gone down, you’ll have to go out and get some kindling. I rather hope it has.” I delayed John for a moment, my hand on his arm.

Connie whispered to her husband as they went along to the lounge-room.

“Everything under control?” I asked.

“No more than we reasoned. It all depends on Cruikshank’s part as to whether or not the unsullied name of Bellamy comes into the case. Can I go now, please? I’m cold and bored.”

I nodded in sympathy. “At least he appreciated your weak stories. And Connie regards you with awe. What now?” I picked up the telephone in the middle of the ring, holding it away from my ear as the sound continued.

“Go easy,” I requested loudly into the mouthpiece.

“Mrs Matheson?” asked a voice. “Is that you, Maggie?” Yvonne. She sounded more like her old self—frightened, timid and bewildered. I nodded to John to go.

“What is it? Is anything the matter?” I asked.

Her voice came over the line in an incoherent rush. “Oh, Maggie, he’s sick again. I just went in—and nurse—I don’t know what’s the matter with her. She won’t wake up. I don’t know what to do.”

I gathered that it was Jimmy who was ill. I also guessed at the reason why Nurse Stone would not wake up. She was dead tight.

“Could you come over, Maggie?” Yvonne begged. “Jimmy doesn’t look at all well. I don’t know what to do.”

“Are you alone?” I asked.

“Aunt Elizabeth is out somewhere. At least I think so. She was not in her room when I called her. Ursula is here, but she doesn’t know anything about babies. Please come.” She sounded almost beseeching.

“All right,” I said resignedly. “I’ll be over as soon as I can.”

I went into the lounge-room. John was coaxing the fire along with the bellows.

“Sorry, people. Do you think you can do without me for a quarter of an hour? Yvonne Holland’s baby is sick, and she thinks Doctor Maggie might be able to do something. I am afraid her confidence is misplaced.”

John’s face dropped along with the bellows from his hand. “Get the card table set up,” I said soothingly. “By the time you’ve sorted out chips and found cards, I’ll be back.”

I went to find a coat and a scarf for my head. The light was still on outside Tony’s room. I crept in, moving the door so that a slit of light fell across his face. He still looked pale and heavy, and his mouth hung slightly open. He was breathing heavily. I regarded him anxiously for a few moments.

IV

It was owing to Tony’s inexplicable ailment and the knowledge that I had left John with some boring people who were not his friends and were merely my acquaintances, that made me choose the path through the wood to the Hall. I was so wrapped up in my concern for haste that it did not occur to me to be nervous until I was actually entering the thickest part of the artificial spinney. Then it was too late to pander to my nervousness, and I kept on.

The wood was full of the noises of rustling leaves, insects and small creatures. One absurd thought became fixed in my head. What would happen if I came face-to-face with Ernest Mulqueen’s fox? It must still be prowling around owing to its would-be trapper’s detention. Did a fox attack human beings as well as poultry? Or was it a creature to be subdued like a dog? From the fox, my mind went to the gin which had been awaiting it. The trap, whose cruel teeth had grasped the Squire instead. John told me Ernest Mulqueen insisted that he had left the gin set away from the path. Following his directions, Sergeant Billings had located the gin and taken it to headquarters for a closer examination. Traces of cloth and human blood, both identified as James Holland’s, had been found adhering to it.

I stepped cautiously along the path, my torchlight playing on the ground two feet ahead. I was moving slowly now, and it was hard to restrain hasty glances over my shoulder and sideways into the thickly growing trees. I dared not give way to nerves. I would only start rushing madly through the wood, screaming like an insane woman. It was the terrible quiet loneliness of the place which frightened me most. I felt completely isolated from the rest of the world.

The wood was an ideal place for a tryst, be it for love or some more evil purpose. No one would hear. The trees would smother light laughter or a sobbing cry for mercy. No sound could vibrate against the damp foliage above and the wet earth underfoot.

It would not occur to such as James Holland to feel apprehensive on his own property. Safe in his arrogance, born of the fear of others, it was unbelievable that a killer should be waiting for him in the darkness of the wood.

He did not carry a torch as I did. He knew the path well. Only too well. That was to the murderer’s advantage. James Holland stepped confidently along the track and stumbled straight into the gin. What time was it? Was there no faint glimmer of light at all? Enough to enable the Squire to see a step ahead? The shot was fired just after seven. Seven had been the hour fixed for his arrival at Holland Hall.

I halted suddenly in the track. But it was not to glance fearfully over my shoulder or to play the torchlight on a suspicious bush. I was nearly through the wood now. I could see lights shining from the windows of the Hall. It was nothing physical that pulled me up with such a jerk, but a blinding discovery. A revelation that I wanted to communicate to John at once.

Yvonne Holland must have thought I was quite mad. I had been called to the Hall to act as a pillar of strength to the fond mother of an ailing child, and all I wanted was the nearest telephone to talk to my husband whom I had left only a short time before. She looked faintly hurt and almost offended when I asked: “By the way, how is Jimmy now?” It was not very important to me then that her baby was sick again. Anyway, mine was ill too. She wasn’t the only anxious mother in Middleburn.

Jimmy seemed better. He had vomited a great deal, but now he was asleep. I was still wanted to give my opinion on his condition.

“As soon as I’ve made a phone call, like a good girl,” I said coaxingly. “I’ll only be a minute.”

Yvonne manipulated two pegs on the switchboard and led the way upstairs.

“You can use the phone in my room,” she told me. She was afraid I might go off and forget Jimmy altogether. “Come along to the nursery when you have finished. Nurse is still asleep. She just won’t wake up. I have given up trying.”

“Best let her sleep it off,” I said absently, waiting for John to answer the extension. Yvonne gave me a puzzled look, and made as though to speak.

John’s voice said: “Hullo,” and I waved her off.

“Darling,” I cooed, in an attempt to control the excitement in my voice. “Are you still cold and bored?”

“What the—Oh, it’s you, Maggie.”

“Who did you think it was?” I asked promptly.

“Never mind. I am no longer cold. The fire is now burning well, no thanks to the green wood you bought. But I am still very, very bored. Suppose you come home instead of wasting time in ringing—”

“Never a waste of time,” I assured him. “Tell me, is there a great deal of difference between the sounds of a gunshot and a car backfiring?”

John’s answer came slowly after a slight pause. “Not much, I should say. What are you after?”

I told him about the sudden flash of insight I had coming through the woods. “Maybe it was a backfire I heard. James Holland was due home at five, not seven. I saw the original telegram at the Post Office yesterday. Nothing like a visit to the scene of the crime to jog the memory.”

John sounded a bit shaken by my nervelessness, and commanded me to return home by the road.

“What do you think might happen to me?” I asked.

“I don’t know. But do as you are told like a good girl. If you don’t, I’ll consider it a form of treading on my corns. And you know the hold I have over you there.”

I said plaintively: “I only wanted to be quicker for your sake. What do you think of the time business?”

“It sounds promising. I’ll look into it.”

I gave him my word to go back by the road and rang off.

Crossing the landing which separated Yvonne’s room from the nursery, something compelled me to glance down into the darkness of the hall below. I no longer felt nervy and on edge from my trip through the wood. Contact with John had a sobering up effect. So it could not have been a result of an overheated imagination which made me see a shadowy figure glide along the wall. I leaned over the railing, straining my eyes.

“Mrs Mulqueen?” I called on impulse. The sound of my voice echoed along the passage. No one came forward to be illuminated in the faint glow of light immediately below. There was no reply to my inquiring tone.

There was a pedestal light on the bottom newel. I went down the stairs and tilted the shade so that half the length of the passage was illuminated. There was no one there. No door was moving along the passage. There was no sound: I tilted the shade in the opposite direction but with the same result. Then my eyes fell on the switchboard full in the glare of the unshaded light. I moved along to look at it more closely. There must have been someone in the hall. The two pegs Yvonne had arranged had been placed back in their original positions.

I crept along the passage to the Mulqueen apartments. The door to the sitting room was slightly open, but the room was in complete darkness.

“Mrs Mulqueen?” I said again, this time almost in a whisper. There was no sound, but I still had a sense of being watched. I put my hand around the door feeling for the light. The room was quiet and empty like the passage behind. I shrugged and prepared to go back to Yvonne. I had neglected my original purpose badly. Any more delay and Yvonne would probably start looking for me.

I put my head in Mrs Mulqueen’s door once again in order to switch out the light. My eyes fell on the frame which held the photograph of James Holland’s erring wife. It was like a blank enigmatic face. It neither beckoned nor repulsed my sudden overwhelming curiosity as I moved across the room.

I had learned something of the character of Olivia Holland from three different sources: sister-in-law Elizabeth, her own farewell letter to the Squire, and lastly from Mrs Potts-Power.

They all pointed to a direct similarity to Yvonne. I turned the frame around gently, holding it in both hands. The face I looked into was totally different from the confused mental picture I had composed. Yvonne could be considered pretty. This face was startlingly beautiful. But I felt a sort of anticlimax because it did not coincide with my own conception. I put my head on one side and regarded it in a puzzled way.

Somehow it was familiar to me. I studied it bit by bit. Usually I can recall people by the shape of their legs and their walks; similarly others can place a person by the hands. Unfortunately the only part of Olivia’s limbs open to the beholder was the tip of one foot, and that was clad in a dainty shoe. My eyes went over the portrait again. Unconsciously I memorized it, noting the shape of the ears revealed by the upswept hairstyle. Ears were my first emergency. I do not know why, but I was glad later when Olivia’s only picture was stolen from Mrs Mulqueen’s sitting-room. Still perplexed about the sense of familiarity Olivia’s face gave me, I turned the picture back to the wall.

Before I had time to turn around the door behind closed sharply. It may have swung to in a sudden draught from the outside passage. I was inclined to imagine a human hand had closed it. No matter under what influence the door closed, it gave me a nasty fright. I was becoming very tired of chasing people through dark houses.

I opened the door, somewhat relieved to find it unlocked. It would never have done for Elizabeth Mulqueen to return and find me in her sitting-room. With firm purposeful footsteps I retraced the way to the foot of the stairs. The pedestal light was still on. I cast one glance up and down the hall and mounted the stairs.

“Is that Mrs Matheson?” asked an uncertain voice from above. It was Yvonne.

“Yes. I’m just coming. Sorry to be so long. I thought I heard Mrs Mulqueen and came down to see her.”

Yvonne took me straight to the nursery, keeping one hand on my arm. After all, the invitation had been extended merely to see Jimmy. So far I had done nothing but wander around the Hall in the dark, looking for shadowy forms and listening for strange noises.

The child did not seem very bad to me. Like Tony, Jimmy looked heavy and pale. I asked Yvonne a few intimate questions which were answered satisfactorily.

“Let him sleep,” I advised. “If he is not better in the morning, ring Sister Heather at the Health Centre. It may be some new bug that’s around. Tony was a bit off-colour too.”

Yvonne said, knitting her brows in anxiety: “I don’t think it can be anything new. He’s been like this before.”

I looked at her quickly, frowning at this information. She did not observe my glance, as she was bending low over the child. I made certain Jimmy was getting plenty of fresh air and drew her outside. She lost the air of assurance she had adopted as she gave me the details of Jimmy’s sudden relapse.

I made no comment to her wail: “And he had started to do so well. I can’t think what could have happened. Do you think it is some sort of chill in the stomach?”

I soothed Yvonne’s worries as quickly as she would allow. They were mainly reiteration and I was anxious to be gone. As we passed Nurse Stone’s room, the unmistakable sound of alcoholic snoring issued forth.

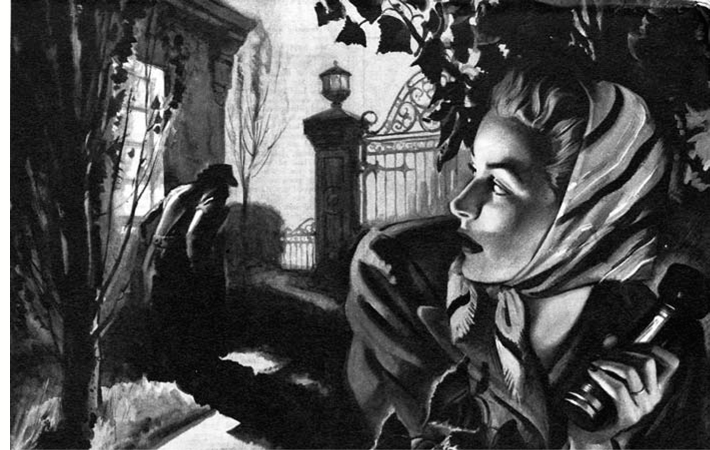

The journey down the drive to the gates was as shadowy and fraught with horrid imaginings as the one through the wood. I kept my mind firmly fixed on John and the fire and the waiting game of solo. Despite these prosaic thoughts, I was glad to see a light from the Lodge shining through the trees. Only the road beyond spelled real security from Holland Hall and its evil influence. Outside the gates I could deal with matters in a practical manner freed from imagination.

Once I looked back towards the house, and regretted it as much as Lot’s wife must have done. The light in the tower was on. It flickered once or twice before it became dark. With my head turned slightly towards the Hall, I foolishly kept on walking. That was how I did not observe the piece of thin cord that was stretched across the drive.

My fall was heavy because it was unexpected. The torch was jerked from my hand and rolled several feet along the gravel driveway. I did not know the obstacle was intentional until I crawled after the torch and became entangled in the string. When I did realize the significance, I became paralysed with fright.

The thought came clearly to me: “What do I know? What clue do I hold?”

I considered it was important to work this out before my assassin struck. But no one moved out of the shadows to advance relentlessly on my prostrate figure. Presently I struggled to my feet and, daring myself out of my terror, shone the torch in a circle about me. It lighted up nothing but the poplar trees of the drive.

My hour was not then. I was being warned, that was all. That cord stretched across my path was like an unsigned letter ordering me to stop prying or it would be the worse for me.

I limped down the drive, mindful of my promise to John. As far as I could see, a trip through the wood would have been less fraught with danger than this one down the drive. I skulked close to the poplars, playing the light every inch of the way.

As I neared the Lodge, my heart thumped hard again. A man’s figure had slipped from the shadow of the tiny porch. I smothered the torch at once and pressed back against the poplars. The figure moved stealthily towards the gates. There the man paused and turned around.

I waited, shaken from the fall and sick with fear. He seemed to be facing the place where I stood.

A sudden light shone from an unshaded window of the Lodge. The man moved at once. But he was not quick enough. I had time in which to recognize him.

It was Cruikshank, the estate agent, who behaved so furtively. He turned down the road towards the village.

I waited for a few moments before I crept from my hiding place. I had no desire to draw Cruikshank’s attention. But like him I glanced back up the drive. The light in the tower had started to flicker again.