ONE

STIPULE

A small leaf-like appendage to a leaf

I have left this unsaid. I have withheld. What is withheld is the left-hand page. Nine left-hand pages have already written their own left-hand pages, as you will see. They are chronic. I have withheld more than I have written. Evergreen and deciduous. Incurable. And uneasy, and like freight.

VERSO 1

The back of a leaf

What is withheld is on the back. A stack, a ream.

There are bales of paper on a wharf somewhere; at a port, somewhere. There is a clerk inspecting and abating them. She is the blue clerk. She is dressed in a blue ink coat, her right hand is dry, her left hand is dripping; she is expecting a ship. She is preparing. Though she is afraid that by the time the ship arrives the stowage will have overtaken the wharf.

The sea off the port is roiling some days, calm some days.

Up and down the wharf the clerk examines the bales, shifts old left-hand pages, making room for the swift, voluminous, incoming freight.

The clerk looks out sometimes over the roiling sea or over the calm sea, finding the horizon, seeking the transfiguration of a ship.

The bales have been piling up for years yet they look brightly scored, crisp and cunning. They have abilities the clerk is forever curtailing and marshalling. They are stacked deep and high and the clerk, in her inky garment, weaves in and out of them checking and rechecking that they do not find their way onto the right-hand page. She scrutinizes the manifest hourly, the contents and sequence of loading. She keeps account of cubic metres of senses, perceptions, and resistant facts. No one need be aware of these; no one is likely to understand. Some of these are quite dangerous. And, some of them are too delicate and beautiful for the present world.

There are green unclassified aphids, for example, living with these papers.

The sky over the wharf is a sometime-ish sky, it changes with the moods and anxieties of the clerk, it is ink blue as her coat or grey as sea or pink as evening clouds. It is cobalt as good luck or manganite as trouble.

The sun is a red wasp that flies in and out of the clerk’s ear. It escapes the clerk’s flapping arms.

The clerk would like a cool moon but all the weather depends on the left-hand pages. All the acridity in the salt air, all the waft of almonds and seaweed, all the sharp, poisonous odour of time.

The left-hand pages swell like dunes in some years. It is all the clerk can do to mount them with her theodolite, to survey their divergent lines of intention. These dunes would envelop her as well as the world if she were not the ink-drenched clerk.

Some years the aridity of the left-hand pages makes the air pulver, parches the hand of the clerk. The dock is then a desert, the bales turned to sand, and then the clerk must arrange each grain in the correct order, humidify them with her breath, and wait for the season to pass.

And some years the pages absorb all the water in the air, tumid like four-hundred-year-old wet wood, and the dock weeps and creaks and the clerk’s garment sweeps sodden through the bales and the clerk weeps and wonders why she is here and when will a ship ever arrive.

I am the clerk, overwhelmed by the left-hand pages. Each blooming quire contains a thought selected out of many reams of thoughts and stripped by me, then presented to the author. (The clerk replaces the file, which has grown with touch to a size unimaginable.)

I am the author in charge of the ink-stained clerk pacing the dock. I record the right-hand page. I do nothing really because what I do is clean. I forget the bales of paper fastened to the dock and the weather doesn’t bother me. I choose the presentable things, the beautiful things. And I enjoy them sometimes, if not for the clerk.

The clerk has the worry and the damp thoughts and the arid thoughts.

Now where will I put that new folio, she says. There’s no room where it came from, it’s withheld so much about…never mind; that will only make it worse.

The clerk goes balancing the newly withheld pages across the ink-slippery dock. She throws an eye on the still sea; the weather is concrete today; her garment is stiff like marl today.

STIPULE

I saw the author, her left cheek, her left shoulder agape, a photo of her washed in emergency, a quieting freight, a grandfather, a great-grandmother, one stage of an illness, on the rim of a page without verbs, bullet-ridden and elegant, a boulder beside her, the things collected in her brain, green lacewing larvae, mourning cloak, bryozoa, aphids (aphids), ladybird, Echinopsis and wisteria and rooms, the manifest green, unclassified ways of saying let us go, the small blue book of the author’s thoughts to decipher, gradatios of violet, blue and black, the clerk, I, need lemon, a spanner, a vehicle, a bowl of nails, a wire, a cup, a lamp, the clerk knows where the salt, where the sugar, where the flowers, the museums and corpses, same number with the following, are we not human unnumbered, poignard case, a horse, a plummet

VERSO 1.1.01

When Borges says he remembers his father’s library in Buenos Aires, the gaslight, the shelves, and the voice of his father reciting Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale,” I recall the library at the roundabout on Harris Promenade. The library near the Metro Cinema and the Woolworths store. But to go back, when my eyes lit first on Borges’s dissertation I thought, I had no Library. And I thought this thought with my usual melancholy and next my usual pride in living without.

And the first image that came to me after that was my grandfather’s face with his tortoiseshell spectacles and his weeping left eye and his white shirt and his dark seamed trousers and his newspaper and his moustache and his clips around his shirt sleeves and his notebooks and his logbooks; and at the same moment that the melancholy came it was quickly brushed aside by the thought that he was my library.

In his notebooks, my grandfather logged hundredweight of copra, pounds of chick feed and manure; the health of horses, the nails for their iron shoes; the acreages of coconut and tania; the nuisance of heliconia; the depth of two rivers; the length of a rainy season.

Then I returned to Harris Promenade and the white library with wide steps, but when I ask, there was no white library with wide steps, they tell me, but an ochre library at a corner with great steps leading up. What made me think it was a white library? The St. Paul’s Anglican Church anchoring the lime white Promenade, the colonial white Courthouse, the grey white public hospital overlooking the sea? I borrowed a book at that white library even though the library as I imagine it now did not exist. A book by Gerald Durrell, namely, My Family and Other Animals. I don’t remember any other books I brought home, though I remember a feeling of quiet luxury and a desire for spectacles to seem as intelligent as my grandfather.

And I read here, too, in this white library a scrap about Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, though only the kind of scrap, the kind of refuse, or onion skin, they give schoolchildren in colonial countries about a strange skinny man on a horse with a round sidekick. The clerk would say I could use this, but I can’t.

The ochre library on Harris Promenade was at the spot that was called “Library Corner” and it used to be very difficult to get to because of the traffic and the narrow sidewalk. But I was agile and small. And I thought I was ascending a wide white-stepped library. And though that was long ago, I remember the square clock tower adjacent to the roundabout. And I can see the Indian cinema next door, papered with the film Aarti starring Meena Kumari and Ashok Kumar.

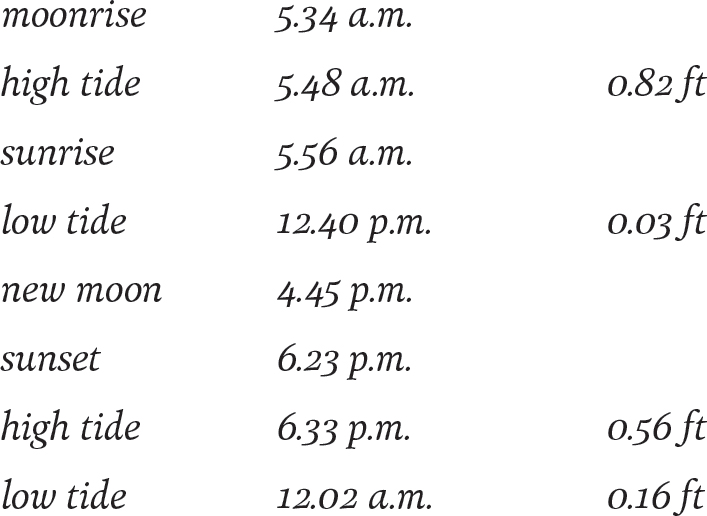

My grandfather with his logs and notebooks lived in a town by the sea. That sea was like a lucent page to the left of the office where my grandfather kept his logs and his notebooks with their accounts. Apart from the depth of the two rivers, namely the Iguana and the Pilot, he also noted the tides and the times of their rising and falling.

Spring tides, the greatest change between high and low. Neap tides, the least.

And, the rain, he recorded, the number of inches and its absence. He needed to know about the rain for sunning and drying the copra. And, too, he kept a log of the sun, where it would be and at what hour, and its angle to the earth in what season. And come to think of it he must have logged the clouds moving in. He said that the rain always came in from the sea. The clouds moving in were a constant worry. I remember the rain sweeping in, pelting down like stones. That is how it used to be said, the rain is pelting down like stones. He filled many logbooks with rain and its types: showers, sprinkles, deluges, slanted, boulders, pebbles, sheets, needles, slivers, pepper. Cumulonimbus clouds. Or, Nimbostratus clouds. Convection rain and relief rain. Relief rain he wrote in his logbook in his small office, and the rain came in from the sea like pepper, then pebbles, then boulders. It drove into his window and disturbed his logs with its winds and it wet his desk. And he or someone else would say, “But look at rain!” And someone else would say, “See what the rain do?” As if the rain were human. Or they would say, “Don’t let that rain come in here.” As if the rain were a creature.

Anyway, my grandfather had a full and thorough record of clouds and their seasons and their violence.

From under the sea a liquid hand would turn a liquid page each eight seconds. This page would make its way to the shore and make its way back. Sometimes pens would wash up onto the beach, long stem-like organic styli. We called them pens; what tree or plant or reef they came from we did not know. But some days the beach at Guaya would be full of these styli just as some nights the beach would be full of blue crabs. Which reminds me now of García Márquez’s old man with wings but didn’t then as I did not know García Márquez then and our blue crabs had nothing to do with him. It is only now that the crabs in his story have overwhelmed my memory. It is only now that my blue night crabs have overwhelmed his story. Anyway we would take these pens and sign our names, and the names of those we loved, along the length of the beach. Of course these names rubbed out quickly, and as fast as we could write them the surf consumed them. And later, much much later, I learned those pens were Rhizophora mangle propagules.

What does this have to do with Borges? Nothing at all. I walked into the library and it was raining rain and my grandfather’s logs were there, and the wooden window was open. As soon as I opened the door, down the white steps came the deluge. If I could not read I would have drowned.

Now you are sounding like me, the clerk says. I am you, the author says.

VERSO 2

I can’t say I was conscious of the left-hand page as early as this but there it was if I had looked. There it was, if you had looked, says the clerk. Essentially years and years actually trying to write in the centre of your life, working with all the intelligence of your being. The feeling of repelling some invasion in order, one day, to be yourself. Rhizophora mangle propagules fell into the mangrove lagoon near the Iguana River, where the sea carried them to us.

VERSO 2.01

The sea brought, too, blue-red kilometres of Physalia physalis.

VERSO 2.1

Then I had six shields in the ground, I thought I’d grow a little corn or take care of a rabbit—both for food. Then I saw a column of orange air, is what I saw. Then I saw a river. I remembered the river. I remember the garbage. I saw a column of night. I remember a whale. What is a pillow tree? I saw pebbles in the dry riverbed. I saw yellow. What kind of yellow? Mars yellow. Iron yellow. I saw polished pebbles. I heard quarrel, quarrel, quarrel underfoot, when you walked. Then I ran back to the road. I didn’t think much of the meaning of life, I only thought of my way through it. Then I saw a green window held open with a stick. What green? Oxide of chromium, terre verte, malachite.

VERSO 2.2

There’s a woman leaving by boat to go to the house where she would have an abortion, and then a story of a woman returning by plane to the hobble of family, and then another about a woman who was taken up by the goddess of winds, storms, and waterfalls, and another about a woman who knelt in the middle of a city street praying, and another about a woman who sat at a small table with a lamp looking at the insects it attracted, then fell asleep and was awakened by a screaming bird. Then there was the story about a woman on a gritting train to Montreal and a wraith, a racist screed veering toward her on the escalator at the Gare Centrale and a woman who sat at a bar in Kensington Market and saw the ghost of Cristóbal Colón. (All these women were embattled except perhaps for the woman in a story who had lovely breasts, adored by many schoolgirls.)

VERSO 2.2.1

On the train, is that when I should say the clerk emerged? She was before me, she was always with me. She was a stevedore stowing cargo for one of my grandmothers, Luisa Andrade from Venezuela. I met her on Luisa’s piano with the photographs. But that was in another language. Luisa threw a man into a pit and covered him with sand; when he got up she had mothered his six children, stitched racial discord among them, subjected them to photographs for the piano and left for her grave. She came from La Guaira on a steamer on the 18th of a certain month. You are making that up. Well Cumaná then. Guaira. She became legend. I did not know her name until a few years ago. You never asked. She was legend.

VERSO 2.3

There was a second woman and she was a woman of the book, a woman of diaries, and a woman of such compact violence that in an instant, brief as it was, she fell in love with the woman of forbidding language. No one has asked me about her.

VERSO 2.3.1

And then there was one, another woman who did not want to be in the world, or the world she was dragged into, who noticed right away the fatal harm but who gave birth to a woman who wanted to be in the world true and absolutely whole and therefore lived with ghosts since that world could not happen yet. And both of them, all they could do was give birth to fragments of their possible selves and then more fragments of themselves would sit in a window on Bethlehemsteeg in Amsterdam or burst with lust in San Fernando or write long letters of excuses in Toronto, until the last of them returned to the ghosts of the second. These two women even when they gave birth to men the men were women. That is. They were undone by something or other and lay on apartment floors gurgling up some exhaustion with masculinity or killed that exhaustion in some violent Greyhound flight from Miami to New York. And the men who read them said they wanted something much more heroic, as if they weren’t yet fed up with a heroism that distorted them, as if they weren’t yet gagging on a heroism that left them right where they were. As if they were not maimed with heroism, as if their eyes were not closed and bruised. Or else they wanted themselves written as Caliban over and over and over again, they loved him perpetually, the way he stayed helper and prodigal brother to Prospero, the way his sores remained open, the way Prospero stabbed him.

VERSO 2.4

All your women, I notice now, leave on boats to get abortions, or leave by poisoning from their own hands, or sit gazing at insects, or leave in flights over cliffs, or leave by their imagination but leave trying to attend to their own intelligence, “but” for the love of god, they’d be human.

VERSO 2.5

I had a great-grandmother, Angelina, who fled in a pirogue across the four Bocas del Dragón. From the ragged coast of one island to the ragged coast of another. She fled with her lover and her three children. Her husband swore to kill her and her new man. The waters in the Bocas are perilous. Between Huevos, Monos, Chacachacare. I can see her standing in the prow as in a painting, her lover—a shadow of herself; because it is she taking the risk of murder; he only loves her and will be the father of several more children but she will leave him too. A watercolour. The sea is verdigris, her head scarf is ochre, her dress is lead white, her three children arrayed around her skirt tail—the two boys in khaki, the little girl, my grandmother, Amelia, in red flowers.

VERSO 3

I came to the city and it wasn’t the city yet. It wasn’t any place and I began there. It wasn’t any place and I was no one and it began there and I began there. At the edge of the city, at Keele and Bloor, there was nothing but a subway and a police car. And to tell by my poetry there’s always a policeman and a hyphen and there are many languages and many signs, which is why there is a policeman to manage the hyphen and to manage the languages and to manage the signs. The city has no contours yet and no buildings, that is why there’s a bicycle in some poems, and a syntax bunched like a new wall, and then a syntax drifting out to the northern fractured sea and to the southern enclosed sea. There is a trio of women on a corner waiting for time to start them and a man who falls down a staircase when the policeman shoots him. There’s the author, the clerk, the poet, that flâneur, collecting streets, and there are uncollectible streets and places and temporary streets and places; the bell of markets and the rake of money making temporary streets and places uncollectible. There’s the eager lyric vowing it all has never happened before, hoping it all has never happened before, and straightaway writing the book, the city disappearing in it.

VERSO 3.01

Yesterday, I heard, at the Nosso Talho Butcher Shop, a transaction—$52.50 for forty pounds of chicken legs—and it was in two dialects of Spanish and two dialects of English and someone was listening in Urdu. Or was it Punjabi? Chali pon kuku dyain lata, bauth maengi hai(n). And in a series of languages this is good news. Molto economiche (Italian). Muito baratos (Brazilian Portuguese). Ponde arte al lado, e baratisimo. Baratisimo, baratisimo. Putting art aside, that’s really cheap, very cheap.

VERSO 3.1

At first there’s no lake in the city, at first there are only elevators, at first there are only constricting office desks; there are small apartments and hamburger joints and unpaid telephone bills. Then a few nightclubs appear and eventually the lake disinters. At times there’s a highway and a car and friends in a snowstorm heading nowhere but back to the city and Sarah Vaughan is singing in the cabin of the car. The three of us are frightened of everything. Our lives in this town, which is not a town, and on this snow road, which is no road, who will protect us. In the city there is no simple love or simple fidelity, the poem long after concludes. There’s a slippery heart that abandons. Fists are full of women’s bodies. The Group of Seven is painting just outside the city now. The graffiti crew is here inside blowing up the expressway and the city is like a Romare Bearden or a Basquiat. More Basquiat. The cynical clerk notes, in her cynical English, all the author has elided, the diagonal animosities and tiers of citizenship. The author wants a cosmopolitan city. Nothing wrong with that. But the clerk who orbits her skull has to deal with all the animus.

The author’s not naive, far from it, but however complicated she is, the clerk is more so. The clerk notices there are air raids, a lingua of sirens and gunshots in the barracking suburbs, the incendiary boys are rounded up by incendiary boys and babies are falling from fifteen-storey buildings into the shrubbery; each condo fights for the view of the exhumed lake, until the sky is cloudy with their shadow. The atmosphere is dull with petulant cars. The author avoids all this; you see my point?

VERSO 3.2

The girl on the bicycle says (there is always a girl on a bicycle because the author cannot ride a bicycle, so one time the girl on the bicycle she rode all across the city and the streets were like the ribs of an eel). “Some eel have saltwater beginnings. Spending their mature lives in lakes. Some eel are electric.” The girl, in the book to come, wonders why we never collect beauty; as she sits, collecting beauty at a window on the lake. She answers, “La belleza no hace daño. / Sac dep khong hai nguoi. / Mei mao boo hai ren. / Ang kagan / dahan ay nindi nasisira.” It doesn’t leave its broken claw in your neck bone.

VERSO 3.3

The author scrapes and scrapes. A palimpsest. The old city resurfaces. Its old self, barely concealed, lifts its figure off the page, heaves deep sighs of bigotry. This beast will never die, the clerk breathes.

The taxi drivers know this. “Miss,” one of them says, “don’t talk about this city, I know this city. You come here thinking, you’ll do this for a year, maybe two, before you know it, it’s ten years. And what did I used to do, and what did I hope, I can’t tell you. I can’t talk about it. It’s no use.”

In the back of the cab a poet tries to sympathize. “I know, I know.”

“You don’t know, Miss.”

And I don’t. I do know that we are both only trying to make a way through life. We are not trying to make sense of it any longer. And I am lucky to be the poet in the cab. I do not know his life. With me this will find its way to a silver-struck enjambment of regret. He will make his way to regret itself.

The woman who lives with him; and the children who live with him? I wonder how this melancholy has scored them.

Nights later another driver tells you, “Miss, no, no, no, women are not equal to men. No, no, you don’t understand. You have to understand; every holy book. Miss, Bible or Koran, not possible. It’s okay, you’re a nice lady, very intelligent but no. You have to learn this, Miss.”

He looks back at me with a pity, as if, if I don’t learn this my life will be hard and I will be punished. He’s telling me for my own good.

VERSO 3.3.1

That cab ride sends the clerk into a polemical frenzy. She opens my notebook and writes the following rant: Modernity can spread a bed of weaponry to what it calls the far reaches of the globe but it cannot spread women’s equality. It cannot stem the liquidity of capital, it cannot even feed its own populations but female bodies are still trophy to tradition and culture. The clerk marks this down. I cannot use it. The actual true elevation above sea level, the clerk says. What is that to me, I ask. This is the ranging rod, she says, shod with iron.

The clerk fills a small, thick red moleskin that swallows five hours of time. The empires, she fumes, the empires called culture and religion only have one province left—women. Her notebook is sleepless.

VERSO 3.3.2

But no, thinks the optimistic author, not just; another cab ride—we talked about Gabriel García Márquez and another we spoke of Camara Laye, then waiting at a stoplight we assessed the IMF and then, in the same breath, the way the autumn arrived between Thursday and Sunday last week. So? The clerk is quiet with condolences for a moment.

One cab ride can catapult you into melancholy, another can sprout wires from your brain. The author must erase this notebook with snow and snows and snows and trains, and febrile women.

VERSO 3.4

In this city, you fall in love at Chester subway, it’s not a beautiful subway so your love makes it so. But its ugliness may doom your love, and you know it but you love anyway.

VERSO 3.5

The subway skeletons its way east, west. North like anxious electrocardiogram, there are invisible stations. At least that is what the author says. Like the eel, bone black, calcined.

VERSO 3.6

In the book to come two new men are trying to arrive in another time, subatomic particles rapid as light along the DVP, a woman is on a train leaving again for Montreal, trying to enter yet another syntax. The clerk expects a sloop of war from across the water. Always.

VERSO 3.7

The city in the book to come is full of people who think there’s a trick to everything. And they’re right of course, the clerk reproaching, after all, twenty mobile phone companies own the electromagnetic spectrum and can sell you a signed two-year contract for the infrared direction and speed at which light travels; some can sell you lightning itself. The author measures the tectonic plates of condos, leaving one apartment for another, one city block for another. The author and the poet always have to leave somewhere, someone, themselves. Only the energies of cities might cool them, metamorphose them.

VERSO 3.8

The clerk senses an urgency in the author, the author is always rushing somewhere.

There are five ways of saying let us go home, the clerk tells the author.

inakeen aan guriga aadnee hadeer (standard, the clerk says) udgoonoow = sweet-smelling one

aqalkii aan u kacno hadatan (middle dialect, the clerk says) indhoquruxoow = beautiful eyes

ar soo bax aan xaafadii hadeerbo tagnee (banaadiri)

qalbiwanaagoow = good-hearted one.

On the other hand, “home” as roots or a place where one feels at home would be:

inakeen aan dhulkii hooyo aadnee hadeer (standard, the clerk says)

nakeen aan maandeeq soo haybanee hada (northern, the clerk says).

You understand, says the clerk, which will you use? You keep them, says the author. The clerk climbs into the packet boat.

VERSO 4

To verse, to turn, to bend, to plough, a furrow, a row, to turn around, toward, to traverse

When I was nine coming home one day from school, I stood at the top of my street and looked down its gentle incline, toward my house obscured by a small bend, taking in the dipping line of the two-bedroom scheme of houses, called Mon Repos, my rest. But there I’ve strayed too far from the immediate intention. When I was nine coming home from school one day, I stood at the top of my street and knew, and felt, and sensed looking down the gentle incline with the small houses and their hibiscus fences, their rosebush fences, their ixora fences, their yellow and pink and blue paint washes; the shoemaker on the left upper street, the dressmaker on the lower left, and way to the bottom the park and the deep culvert where a boy on a bike pushed me and one of my aunts took a stick to his mother’s door. Again, when I was nine coming home one day in my brown overall uniform with the white blouse, I stood on the top of my street knowing, coming to know in that instant when the sun was in its four o’clock phase and looking down I could see open windows and doors and front door curtains flying out. I was nine and I stood at the top of the street for no reason except to make the descent of the gentle incline toward my house where I lived with everyone and everything in the world, my sisters and my cousins were with me, we had our bookbags and our four o’clock hunger with us and our grandmother and everything we loved in the world were waiting in the yellow washed house, there was a hibiscus hedge and a buttercup bush and zinnias waiting and for several moments all this seemed to drift toward the past; again when I was nine and stood at the head of my street and looked down the gentle incline toward my house in the four o’clock coming-home sunlight, it came over me that I was not going to live here all my life, that I was going away and never returning some day. A small wind brushed everything or perhaps it did not but afterward I added a small wind because of that convention in movies, but something like a wave of air, or a wave of time passed over the small street or my eyes, and my heart could not believe my observation, a small wind passed over my heart drying it and I didn’t descend the gentle incline and go home to my house and my grandmother and tell her what had happened, I didn’t enter the house that was washed with yellow distemper that we had painted on the previous Christmas, I didn’t enter the house and tell her how frightened I was by the thought I had at the top of our street, the thought of never living there, which seemed as if it meant never having existed, or never having known her, I never told her the melancholy I felt or the intrusion the thought represented. I never descended that gentle incline of the street toward my house, the I who I was before that day went another way, she disappeared and became the I who continued on to become who I am. I do not know what became of her, where she went, the former I who separated once we came to the top of the street and looked down and something like a breeze that would be added later after watching many movies passed over us. What became of her, the one who gave in so easily or was she so surprised to find that thought that would overwhelm her so, and what made her keep quiet. When I was nine and coming home one day, my street changed just as I stood at the top of it and I knew I would never live there again or all my life. The thought altered the afternoon and my life and after that I was in a hurry to leave. There was another consciousness waiting for a little girl to grow up and think future thoughts, waiting for some years to pass and some obligatory life to be lived until I would arrive here. When I was nine I left myself and entered myself. It was at the top of the street, the street was called MacGillvary Street, the number was twenty-one, there were zinnias in the front yard and a buttercup bush with milky sticky pistils we used to stick on our faces. After that all the real voices around me became subdued and I was impatient and dissatisfied with everything, I was hurrying to my life and I stood outside of my life. I never arrived at my life, my life became always standing outside of my life and looking down its incline and seeing the houses as if in a daze. It was a breeze, not a wind, a kind of slowing of the air, not a breeze, a suspension of the air when I was nine standing at the top of MacGillvary Street about to say something I don’t know what and turning about to run down. No, my grandmother said never to run pell-mell down the street toward the house as ill-behaved people would, so I was about to say something, to collect my cousins and sisters into an orderly file and to walk down to our hibiscus-fenced house with the yellow outer walls and my whole life inside. A small bit of air took me away.

VERSO 5

In June, I realized I had already abandoned nation long before I knew myself, the author says. That attachment always seemed like a temporary hook in the shoulder blade. A false feeling, in a false moment. Just like when one April in the year I turned eight, I noticed I had been put in a yellow dress. Ochre yellow? asks the clerk. Yellow ochre. Iridium oxide. But all around me everyone seemed to feel it, this nation/girl. I thought of the dress as a beheading. I had moments of loneliness when I could not feel it also. And I felt as if I were betraying many people all at once. And everyone said one had to feel it so I felt it like when reading a book one feels a feeling, but it is in a book and not in one’s real life. But I could not understand the agreements everyone else had made to the feelings in the book, the fears of dispossessions. I must have started dispossessed then, the clerk says.

Every year for forty years I’ve been asked the same question by someone who needed to consume allegiances. Some interrogator observes my skin and asks me why. Every year I’ve answered into a void like Coltrane blowing “Venus” out into the nothing. Like Ornette Coleman cooking sciences. And sometimes I’ve tried not making the interrogator feel bad, or I fend off the attack with dissembling. Most times (every time, the clerk mumbles) I haven’t done what I should, which is to rise and leave like my women. Sail off on a boat, leap off a cliff, or just sit and sip my beer at the old Lisbon Plate in Kensington Market. These tedious questions have drawn this line in my left cheek; they’ve nailed this pain in my left shoulder. Every time, the clerk says loudly.

I am speaking here of something you would not understand as a clerk. No I wouldn’t, nods the clerk. None of it makes sense. Your sense-making apparatus is invisible to me, says the clerk, or at least I would like to keep it invisible. It is like tracing paper over tracing paper. I don’t use tracing paper.

VERSO 5.0.1

What the author has. A line in her left cheek, a pain in her left shoulder, a crushed molar, an electric wire running from her elbow to her smallest left finger. Wings in her left eye.

VERSO 5.1

In December, any December, standing in Elmina, the dirt floor, the damp room of the women’s cells, nation loses all vocabulary. Loses its whole alphabet. I have no debts. I have no loves. A soccer game every four years; maybe that. I have two eyes that see where the body that carries them sleeps. I have the drama of skies, no question; an affinity for blue that makes me fill beautiful bottles with blue watercolour and water, that’s a habit. Of course the earth is beneath your feet and so there must be place or the feeling of place or gravity. But which nation ever said of a woman she is human? So what allegiances do you have? Temporary and provisional, wherever.

So what? You feel featherless, the clerk says. Didn’t you always; weren’t you just an outrider? You tried to fit in, to your own demise though, you rode shotgun to your own disaster, she says. You’re right. No need for violent metaphor, the author cautions. Again, let me draw your attention to the tracing paper.

VERSO 5.2

Soon in August I saw a woman come into the beauty parlour, she hadn’t been sane for years but she came in, in a lucid moment, lucid for what we call sane. She asked the woman standing at my hair, “How much is the wig?” The women gently told her $49.95. Then she said with a wistful sigh, “I want a ponytail,” and the woman showed her a ponytail, as if she were a real customer. I’ve turned this into something else weeks after, but the hairdresser, Base, was gentle with the woman, the most kind thing I’d seen all day, pretending the woman was sane. But then it struck me later that the mad woman’s moment of lucidity was the entranceway to women’s madness on the earth. The beauty parlour—what a narrow doorway, what a pitiful place. On any other day the mad woman would be nude at Lansdowne and Bloor with her dress lifted over her head or tied as a belt around her waist. On any other day. These two things, nude on the street or the beauty parlour. I was in the beauty parlour, there myself sane as ever, shaking my head at the mad woman. I just haven’t the courage to be nude on the street like her. Someone will come up to me after this and ask, “But isn’t there some middle ground, but surely we can try to exist, but aren’t you happy sometimes?” I hate this “someone.” If you like. Whoever you are. But don’t be annoying. I’ve answered that already. Just because you have only stage one of an illness doesn’t mean you’re well. Yes you could have a fever, yes you could be dead, no doubt that would be worse. But recognize the disease.

VERSO 5.2.1

What the author has, one stage of an illness, what illness, an earache, steady, an inclination to take her leave of places after an hour or so. A gregariousness followed by a sharp desire to be alone.

VERSO 5.5

I have plans; I have no plans. They disappear in the Gulf of Mexico like brown pelicans and hermit crabs in an oil spill. Isn’t it time we stopped saying spill? That wasn’t a spill it was a deluge. It has no mercy, nation. I have no mercy. I’m jaundiced. All the while through the hoots of democracy, I was looking for the women in Tahrir Square, in Yemen, in Tunisia. I am listening. Whatever, the author says. I don’t want to hear any more about waiting. In September, and now October, I am unpinned from all allegiances. Of course you’re not. But what if I wrote like this? Unpinned.

VERSO 5.5.1

Au coin de la rue des Ursulines et François Xavier the author notices a luminous sky. It must have been there always. And what am I doing here. Grey minister, grey petrol, grey detour, the clerk answers. Where life leads you it is not so much impossible to know but to anticipate. No that is a lie, one chooses, one anticipates, one chooses among a certain number of anticipations; one anticipates among a certain set of choices. How it goes. How will I get out.

What the author needs, an epiphonema: “The Taxonomy of Crop Pests: The Aphids” by Miller and Foottit.

VERSO 6

The seeds or spores of a fern are carried on the back of the leaf. Because a fern does not have a flower, sex occurs when rain falls and the spores fall to the ground and sprout and then some intricate and complicated thing that has taken millennia to develop happens.

VERSO 6.1

At first the author thinks these pages will come in handy later. It’s a benign enough thought. They’re benign enough pages. Pages you can’t use right now because the poem moved in another direction. Pages that are unformed, or pages that, at whatever moment, she did not have the patience or the reference to solidify. Or they are pages where the mind strayed: to a hopscotch box on asphalt; in Antigonish there was a fireplace; or that time in Escondido with Connie at the beach. The bar at the corner of the first street and the second street in San Pedro de Atacama where they played Black music, they said, on the board outside. The stranger, happy to see her for no reason at all. These stray thoughts might not serve a purpose. They’re just like the dust under the bed where she used to go to read. Sometimes this dust would have an ant in it, or a spider, or a chrome green grasshopper caught by a spider. There from the stone in the front yard to the house, a continuous line of Atta cephalotes carrying cut bits of red ixora. There a substrata of life going on that people are unaware of. An abandoned web bereft of its chemical tensions. The broken pick of a guitar; certain streets she never visits anymore; a shout at 3 a.m. All this. What is in time? Radiation, the clerk says, seeing the wavy air of existence. The way things hover. The author hurries on her way to time’s next accelerant foot.

VERSO 6.2

In Cuzco, a man coming from a wedding, the sun just gone down over the town’s elevation. The man in one translucent gesture throws his dark wool poncho over his head; it descends to his shoulders, the garment settles, slowing time in one elegant gesture.

VERSO 6.3

Several questions the clerk has: from this angle, when will we leave the body, the ribbed brace of human bones, the whistling flutes of lungs at hemispheric windows and time spent on the earth, the raucous coordinates of molecules and who records their errors and their diatonic scales; here’s where what we do is listen, only listen to the blood and the rowdy idioms of these cities jagging east, then west; this submission to vastness that must be done at 6 a.m. each day and 8 p.m. precisely; we dipped our hands in the well of our chests to save ourselves, just this morning we made our assignation with birds, to set our watches in motion the coldest streets of several cities bellowed and disgorged their pyrotechnic night-time parties; glide me across a wooden floor as if in the arms of swifts in flight, sustain the chord of G from one year to its nomadic next; of course we’ll exist, I suppose, but how, what would the world be with us fully in it, what about the 900 petroglyphs of our embraces.

VERSO 7

Controversy, against the turn, against the furrow

I finally joined the Communist Party of Canada when it was almost at the end of its existence. Party meetings were long bureaucratic procedures where many papers were read and intense eyes directed at the people who had encyclopedic brains full of Marx and history. I joined the artists. There were artists of all kinds in the club, we were writers and painters and actors, and there were even puppet makers and comics. These meetings were possibly the most boring meetings we ever attended. None of us ever had a meeting perhaps to do anything that we did as artists. There were photographers and musicians too and proofreaders, and bookshop owners. And if we did have meetings they would never be this dreary. The meetings were deadly, tedious meetings discussing things I can’t remember now. I loved these meetings. There was a conversation there that we never had to have about what we were doing. In these muddy meetings there was a clarity about our love. The same love as Lorca, and Neruda, Saramago, and Carpentier.

A poet friend of mine, two in fact, who were not in the party asked me once why I was a communist. I was taken aback. I said, what else would I be? They stoned me with Stalin. I pelted them with Sartre. I said I’m a communist because I’m not a capitalist. They said this was simplistic. I said yes, but it’s clear. It was an evening in Massachusetts, we were going to a reading, they said what had communism done for Black people. I said what had capitalism done. They brought up pogroms. I brought up slavery. They said but you’re Black, I said but you’re Black too. They said these isms are only there to hoodwink Black people. I said most likely but I come from the working class. I had never thought of being anything else, for me it was simply logical, organic. One of them so annoyed with me asked, was I going to call Gromyko to ask him what I could say that night. I said, you call Reagan, I’ll call Gromyko. We went silent and walked diagonally separated toward the reading. I read an erotic story about some teenage girls in love with their French-language mistress, this confirmed my shunning, we parted company, the diametric widened.

VERSO 8

Two enigmatic bales of pages arrived one day. The clerk was adding up the countervailing duty as she usually did on Mondays. Mondays because Sundays are a bad time for the author. Just the sound of Billie Holiday alone accounts for this. Eleanora Fagan can break any Sunday in two. So this surprising Monday when the clerk had expected the usual empty Monday of additions, two bales, one violet and one blue, arrived. The blue was not like the blue of the clerk’s garment rather it was a blue like the blue off Holdfast Bay on the Indian Ocean. The violet was indescribable. How can you describe violet? It melts. There were no consignee marks, except blue and violet.

VERSO 8.1

Violet rails, violet cancels, violet management, violet maintenance, alizarin violet, the violet bale began. Blue search, blue proceedings, blue diastole, blue traffic, the blue bale began.

Lighter than usual, the blue clerk tried to figure out what to make of these.

VERSO 9

To furrow, a row, a file, a line. Inventory

Some say that poets should not attempt it. Some. Some and they. I absorb all the anxieties. But you don’t resolve them. You are no relief from them. You merely elaborate them. You make me more anxious. How many times have you said, it is not my job. I can do nothing about anything, the clerk repeats. I can only collect.

Stay on matters of nature, on matters of love, on the domestic, on language, sound. Furrow the same row. The esoteric, not history, or politics. This is the conservative line of poetry; to stay away from politics, stay away from intervening in the everyday except soothe, sage, bring good tidings, observe beauty; give light when all is dark; assure us that we are benevolent and good at the core, lift us from the daily troubles of the world, elevate our molecular concerns, our parochial, individual lives to the level of art; convince us that we are not petty and ridiculous; and brutal, adds the clerk. And brutal, says the author. And brutal, adds the clerk. That we are tied in to some universal good, some deep knowing. The clerk sighs. That’s god, or mother, not poet. Listen to the bitterness dug into that furrow. Poetry must be eternal not temporal. Who is at eternity testing this theory?

The clerk is at the end of the wharf, the weather is as aggressive as a metaphor. The metaphor, she’s talking to herself clearly, the metaphor is an aggressive attempt at clarity not secrecy. The poem addresses the reader, it asks the first question, it is not interested in the reader’s comfort nor a narrative solution. It is not interested in your emotional expectations, or chronologies. It is flooded with the world. The great interrogation room is the stanza, you are standing at its door.

The clerk is at the end of the wharf, and the end…the weather is as torpid as a strophe. The strophe is a turning and a turning and a resolute turning. After, after, after the world is different. And after still, and after.

The grim list is presented by the clerk to the author, My inventory of war and democracy, she says. I’m Hecuba at the end of the Trojan War…Lift thy head, unhappy lady, from the ground; thy neck upraise; this is Troy no more,…Though fortune change, endure thy lot; sail with the stream,…steer not thy barque of life against the tide….

I’m living in the world, the clerk shouts at the author. I’m talking about it next, the author insists. What woe must I suppress, or what declare?

VERSO 9.1

I have an ink from cuttlefish; I have one from a burnt pebble, one from several crushed juniper berries. This came off in my hand. When did they arrive? They broke in. Broke in where? Can’t remember. When? Doesn’t matter. When are they leaving?