SUPPRESSION AND DISTORTION:

FRANZ KAFKA ‘FROM THE PRAGUE PERSPECTIVE’

RETURN OF A COUNTRYMAN

A very good overview of Franz Kafka’s reception in Czechoslovakia has been provided by Josef Čermák.1 His first publications on this topic date back to the 1960s.2 My study picks up precisely where his study of 2000 left off, namely in 1963, although admittedly I do not get far beyond 1963. It is in this year that Kafka’s Czech-language texts were first published. I am going to focus on the inclusion of these published texts in academic and journalistic discussions, which goes hand in hand with the interpretation of Kafka ‘from the Prague perspective’. The – albeit only fragmentary – publication of Kafka’s unknown Czech texts was, in the context of Kafka’s reception, an entirely new phenomenon;3 in the Czechoslovak context, however, this was also true to an extent of Kafka himself and his work as a whole. The Czech translations of his works were, after all, banned from 1948 until 1957. From the perspective of socialist realism Kafka’s writings were regarded as formalist and decadent; stigmatised as a representative of the bourgeoisie, Kafka became a taboo author.4 Even in 1957 the slowly burgeoning reception of Kafka faced strong ideological opposition from those who went on to shape the cultural politics of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, which was officially declared in 1960. The social and territorial ‘grounding’ or proletarianisation of Kafka, the process of making Kafka ‘one of us’ and his representation ‘from the Prague perspective’5 surmounted the ideological barriers of 1963 but not without excluding or overlooking other aspects of the author, such as the Jewish dimension of his work.

Why 1963 is of greater importance than any other year should be obvious. It marks – along with the Liblice conference initiated by Eduard Goldstücker6 – an important turning point in Kafka’s reception, the implications of which were relevant also outside of Czechoslovakia. Although this phase of his reception also saw him being appropriated by various contemporary discourses, this time it did not result in a ban of his work. Rather, it transformed Kafka – at least in Czechoslovakia – into a cult author of the 1960s. This turning point in Kafka’s reception has, however, less to do with the ‘internal’ (implicit) or ‘external’ (biographical) author and much more with the ‘image of the author’.7 The 2008 conference Kafka and Power 1963–1968– 2008 focused precisely on the myth surrounding the Liblice conference and the effect it had well into the 1960s, not least on the Prague Spring. Kusin has also looked at the role of the Liblice conference for the reform movement.8 For the same reason, scholars such as Goldstücker or Kusák, among others, have also looked back on this from their perspective as key participants.9 To read the contemporary clash over ‘Spring, swallows, and Franz Kafka’ – in which Kurella uses swallows as well as other black bird species with less positive connotations to build up his polemical arguments10 – is to encounter the imagery and rhetoric of both the Prague Spring and of ‘Normalisation’, making the teleological perspective of the Kafka and Power 1963–1968 [. . .] conference easily understandable. The election of Eduard Goldstücker as Chairman of the Czechoslovak Writers’ Guild seems to complete an arc which began with the Liblice conference and ended with the Prague Spring. In the 1970s the proximity of these two events as well as the accusation of his ‘bourgeois decadence’ from the 1950s proved to be disastrous for Kafka’s reception:

[. . .] it made the civil servant J. furious that the Kafka motto ‘I write differently from how or what I speak, I speak differently from what I think, I think differently from the way I ought to think, and so it all proceeds into deepest darkness’11 had been retained in the translation. And not only because the motto was deceitful, but also because it had been penned by Kafka, the writer who had been condemned and whose name ‘was not to appear anywhere’. [. . .] The point of this story is, however, in true Švejk style utterly stupid: three months later I saw 18 copies of the Kafka book by Brod [. . .] lying on the desk of the antiquarian bookshop in Ječná Street. . . the unsold remains of the print run which had [now] been released for sale.12

In order to understand the ethos of the Kafka reception of 1963, we need to go back a few years. Following the advent to power of the communists in 1948 there was a glaring hiatus in the official reception of Kafka which would last until 1957, a much longer hiatus, then, than that between 1939 and 1945. The absence of an official normative reception should, however, not be mistaken for an interruption of the reception in itself, as Jan Zábrana’s diary entry describing the decentralised, individual reception of Kafka makes clear. Nevertheless, it is clear that this reception, too, had an ideological frame and was formulated in reaction to the official ideological discourse on Kafka and the exclusion of his writings from the official literary sphere:

For the young, non-conforming Prague intellectuals of the 1950s who skulked around the literary scene or who themselves wrote, it was common for each of them to have a couple of Franz Kafka’s short stories at home which they had translated themselves and which they lent to friends and acquaintances or read them out at get-togethers. [. . .] It was somehow the done thing. I heard and saw several Kafka stories in perhaps twenty handwritten translations doing the rounds. Where did all these cobbled-together translations disappear to? They were an expression, a reflection of the longing for the knowledge of the forbidden, outlawed world of true writing which Kafka at the time embodied for them. That it was only ever a couple of stories, one, two, three – never a whole book –, was simply evidence of the authentic love of amateurs rather than of superficiality. They were not professionals; they were not capable of more, had not the staying power; they were mostly timid lovers of an illusion which Franz Kafka embodied for them at the time. My memories of those evenings when somebody somewhere would read out Kafka’s stories are filled with great melancholy. All of these stories were later published in book form, making sure that it could never be the same again.13

However, the criticism of the cult of personality in 1956 made it possible for Kafka’s writings to be published again. The breakthrough came in 1957 with the publication of Doupě, the Czech translation of Kafka’s story ‘The burrow’. It was published in the magazine Světová literatura (World Literature) alongside an essay on Kafka by its translator Pavel Eisner in which he picked up once again and elaborated on his concept of the triple (linguistic, social and religious) ghetto.14 As Čermák remembers, the publication must have ‘resonated powerfully’ with his readers.15 Reactions in the press to Pavel Eisner’s ventures as well as to the publication of the Czech translation of Kafka’s novel The Trial in the following year, also translated by Pavel Eisner, were however – in comparison with the response to Kafka that was to follow in 1963 – scarce.16 Čermák discusses each of the responses that did appear, positively evaluating the studies by Ivan Dubský and Mojmír Hrbek and Oleg Sus, and criticising Pavel Reiman and Jiří Hájek.17 According to the international bibliography of Kafka’s oeuvre and reception, there were also other publications on Kafka during this time.18 I found yet other peripheral publications on Kafka, e.g. in the Christian Review,19 but it would be another four years before the next translations of Kafka work were published.20 Only rarely did someone venture forth, for example Goldstücker or Grebeníčková,21 who reviewed Victor Erlich’s study of Gogol’s ‘The Nose’ and Kafka’s ‘The Metamorphosis’ in the journal Plamen (Flame).

The reception of Kafka between 1956 and 196222 and its entanglement with contemporary political discourses can be summed up in a single visual image. In 1956 the military uniform on the body of the communist president Klement Gottwald, on display at the Czechoslovak Mausoleum of Revolution on Mount Vítkov, modelled on the Lenin and Stalin Mausoleum in Moscow, was replaced by civilian clothing. But it was not until 1962 that Gottwald’s corpse was cremated and the monumental Stalin statue on Letná hill blown up.23

That year also saw the publication of the Czech translation of the unfinished novel The Man who Disappeared, although Pavel Reiman was still obliged to translate the novel in the shadow of an ideologically acceptable interpretation.24 For instance, he places the Stoker at the centre of the novel as a representative of the working class who finds sympathy in Karl Rossmann, who, as a member of the ‘bourgeoisie’, has realised that capitalism is on the verge of collapse. As a result of these sympathies he initially acts as the mouthpiece of the Stoker. Reiman also argues that Rossmann’s downfall is due to the fact that he loses sight of the Stoker and, thus, of the working class. Among those who greeted this publication with reviews were Ivan Dubský in Kultura (Culture) and Host do domu (Guest at Home), Ivo Fleischmann in Literární noviny (Literary Newspaper), Pavel Grym in Lidová demokracie in (People’s Democracy) and Eduard Goldstücker in Tvorba (Creation).25 These covered the entire spectrum of periodicals concerned with the reception of cultural events. Nevertheless, according to the Bibliografický katalog ČSSR – články v českých časopisech (Bibliographical Catalogue of Czechoslovakia – Articles in Czech journals) apart from these and three brief articles by Zdeněk Kožmín, Agneša Kalinová and ‘zf’,26 nothing else appeared in this year – except the translation of Franz Kafka’s letter to his father in the journal Světová literature (World Literature).27

It was in Moscow, rather than in Prague, that the wall around Kafka in the Eastern Block was finally toppled – by Jean-Paul Sartre. In 1962, at the World Peace Congress in Moscow, the French thinker held a metaphor-laden speech with the title La démilitarisation de la culture,28 in which he labelled Kafka as a ‘weapon’ used by the West and called for ‘cultural demilitarisation’ in the relationship between the East and the West.29 At the same time he insisted on the need for people in the East to finally be allowed to ‘read’ Kafka. His speech instigated an – in quantitative terms – influential, but at the same time politically chequered, reception of Kafka in the Eastern Block. In the following year there was a veritable flood of Kafka publications largely inspired by the Liblice conference – enabled, if not inspired, by Sartre’s speech. In 1963, in addition to the Czech translation of Kafka’s ‘The Metamorphosis’,30 roughly seventy translations of Kafka’s short works or journalistic texts made reference to,31 amongst other things, Jean-Paul Sartre’s reflections on Kafka, the Liblice conference, Kafka’s birthday and publications. These, along with radio broadcasts and the Czech edition of the Liblice conference volume, rained down on the parched public sphere like a long awaited rainstorm.

If at the beginning many referred to the breakthrough instigated by Jean-Paul Sartre in order to support their own response to Kafka, their reception of Kafka did not align with Sartre’s calls for a concentration on texts. Incidentally, over the course of the year explicit references to Sartre disappeared completely. Fischer, for example, devised the metaphor of spring and the swallow in 1963.32 Goldstücker even went so far as to present Kafka, in view of the hiatus in his reception particularly between 1948 and 1957, as a ‘victim of the cult of personality’;33 in doing so he may well have been projecting his own personal agenda on to Kafka. In 1951 Goldstücker had been sentenced to lifelong imprisonment in an antisemitic show trial, only to be rehabilitated and released in 1955.34

The political language in which Kafka’s reception was couched may well have had little to do with Kafka and his works, but it nevertheless became an important aspect of the author’s image, and, consequently, of the contemporary interpretation of his works. In this time, Kafka became a reference point not only for the at this time more open-minded Marxist critics and historian of literature like Pavel Reiman, Eduard Goldstücker, Jiří Hájek and others, but also for the official newspaper of the communist party.35 Furthermore, in the Czech, that is the Czechoslovak, context the appropriation of Kafka as ‘one of us’ was of central importance. Miroslav Kaňák used the title ‘Ztracený a znovunalezený’ (Lost and found) for his article published in the weekly Hussite newspaper Český zápas (The Czech Struggle),36 in which he reflected on Franz Kafka’s reception, superimposing the protagonist of The Man who Disappeared onto Kafka and in doing so characterising him as the prodigal son. Eduard Goldstücker’s imagery also went along the same lines and marked an equally clear departure from Sartre and contextualised Kafka’s texts to selective biography including his posthumous fortunes. In his speech on the occasion of the opening of the exhibition of Kafka’s personal documents and book publications in the literary archive of the Památník národního písemnictví (Museum of Czech Literature), at the beginning of July 1963, Eduard Goldstücker welcomed the ‘countryman born in Prague’ on his return from ‘a long and undeserved emigration’.37 Of particular note here are the family semantics of the prodigal son (‘lost and rediscovered’) and of the homeland (‘compatriot’, ‘undeserved emigration’) which are in keeping with Goldstücker’s call for the ‘grounding’ of Kafka and thus also with the interpretation of his work ‘from the Prague perspective’, to which I will return later.

The prodigal son and compatriot was also welcomed on the occasion of his eightieth birthday on 3 July 1963, around five weeks after the Liblice conference, right across the Czech media landscape, including the most official newspapers like Rudé právo (Red Justice), Mladá fronta (Young Front), Práce (Labour), Svobodné slovo (Free Speech), Lidová demokracie (People’s Democracy) etc.38 The women’s magazine Vlasta, the youth magazine Mladý svět, or the Magazine of Jewish Communities in Czechoslovakia also joined in.39 The poet Ivan Diviš got carried away enough to write and publish a poem in the weekly literary publication Literární noviny titled ‘Franz Kafka’, which, unlike Louis Fürnberg’s poem ‘The Life and Death of Franz Kafka’,40 may mention Kafka’s name but barely features him:

Only after years, close even to the moment where my backbone fractures,

only after years, struggling through the halls whose locks

hardened into sharp ice – I realised something I did not want to!

When they say to you at twenty: remember

a house can also be built as a warning –

You do not believe it, you crawl in, to, befuddled by booze,

Reel from non-father to non-mother, proud of your baboonish delirium

And, persisting in this confusion, like fly shit,

Hanging off the side of an avalanche! As if I would ever cry over you, Franz!

A rosary of empty nutshells!

Those are the years, when I was nowhere,

When I, teetering between Archimedes and Copernicus,

Gradually dissolved into adjectives

And only, thanks to a box around the ears from the storm, realised that he who walks

before me

On wide legs – yes, now it’s clear to me, is a woman!

Dirty, because she made the world. In her whole life

No booze passed her lips, and as earth lurched near

She merely whispered. I wouldn’t have expected that from you –

And began to cry tiny tears

Like a quail in blood, before it’s picked up.

That’s what you’ve always said. And the would-be crucified

Walked the dreads of mysticism.41

Diviš’ poem and its alienation of Kafka through Christian imagery may be somewhat odd, but the way that he projects his own poetic agenda onto the ‘unknown’ in a similar way to other interpreters makes it highly typical of its time. For however eloquently Kafka is denied in this poem, it is an excellent demonstration of the way in which others’ agendas were superimposed onto Kafka at that time, as is seen, for instance, in the semantics of the ‘prodigal son’ or the discourse of destalinization, which featured prominently at the time.

MARXIST READINGS

The discourse of victimhood and rehabilitation projected onto Kafka certainly does not mean that people relinquished their Marxist – even crudely Marxist – approach to Kafka’s work. Although in his paper at the Liblice conference Eduard Goldstücker referred to Eisner’s biographical argument of the triple ghetto in relation to his question of why the signs of the crisis of bourgeois liberalism in Prague were felt so early and forcefully,42 elsewhere his approach is actually closer to Pavel Reiman. Goldstücker, too, remains entrenched in a Marxist, biographical and sociological reading of Kafka, and simply casts Reiman’s interpretation into a more positive light. For instance, he links Franz Kafka to Karl Rossmann and declares Kafka to be an utopian socialist; even the land surveyor K. in The Castle is hailed as a revolutionary.43 At another point Goldstücker claims:

Whenever we approach the extremely complicated organism of Kafka’s work, it very quickly becomes clear that we would not get very far if we were to base our analysis on the texts alone, because it is immediately apparent that these are a crystallisation of his own personal set of questions and that the protagonists of his works, whether they are called Bendemann, Samsa, Raban, Gracchus, Josef K., land surveyor K. or something else, always signify Franz Kafka.44

This turn away from the text and the shifting of focus from the internal to the external author (‘personal . . . questions’; ‘the protagonists of his works. . . . signify Franz Kafka’) may well be entirely correct according to the Marxist theory of representation, but they lack depth because their Marxist glasses distort the crisis as a ‘situation of modernity’, and thus blind them to the treatment of contemporary discourses in Kafka’s work. This accounts for the tendency to neglect a close analysis of his poetics.45 This diagnosis of Czechoslovak Kafka scholarship was issued as early as 1964 by Grossman who one year after the Liblice conference caused a sensation with his dramatization of The Trial.46 Nevertheless, the focus on the base runs as a common thread through Goldstücker’s publications of 1963. Remarkably, Goldstücker frequently cites a decontextualized passage of Sartre’s speech even though his approach is the complete opposite of Sartre’s insistence on removing Kafka from discussions in his local context in order to focus solely on his work. Goldstücker instead invokes the social roots of artistic creativity, applying this to all literature and thus to Kafka’s work:

The depth of each work feeds off the depth of national history, of language, tradition, off the special and often tragic questions which time and space impose on the artist through their dynamic communion of which he too is an inextricable part.47

It is this view of art that provides the basis for Goldstücker’s call for the ‘grounding’ of Kafka, which he understands in both a territorial as well as a social sense. Since Kafka’s proletarianisation as well as his connection with ‘the people’ play an important role in the transformation of Kafka into a utopian socialist and revolutionary, Goldstücker later also reinterprets Hermann Kafka’s biography in line with this. In doing so he forced a connection with the Czech substructure of Franz Kafka’s work. Accordingly, he also claims that Hermann Kafka (1852–1931), whom he calls ‘Heřman’,48 and whose ‘Czech’ surname he etymologises as jackdaw,

grew up in an exclusively Czech environment and all his life spoke better Czech than German.49

At the same time as this, Klaus Wagenbach also reinforced these Czech, folk-like motifs in his popular illustrated Kafka biography by labelling Hermann Kafka a ‘Czech Jew’ and having him come from a ‘Czech-Jewish provincial proletarian’ background.50 According to Wagenbach, from his contemporary point of view, further indirect indications of Hermann Kafka’s Czechness are ‘language errors’ in the letters he wrote in German to his future wife Julie Löwy, née Kafka, in 1882.51 Wagenbach even made Hermann Kafka, using his ‘Czech surname’ to support his argument, a ‘member of the executive board of the first Prague synagogue in the Heinrichsgasse in which sermons were held in Czech’.52

The appropriation of Hermann Kafka went so far in the Czech German Studies, that Wagenbach’s relatively cautious claim that the everyday language of Hermann Kafka’s childhood and youth in Osek was ‘more likely Czech’53 was in the Czech translation much more forceful: ‘jehož mateřská řeč byla česká’ (whose mother tongue was Czech).54 This has also had consequences for the appraisal of Franz Kafka. Following this logic, Kafka would have lived in a Czech – or through his mother and father at least a bilingual – household, and thus learned to speak excellent Czech and German. This would also account for the declaration of both German and Czech as his ‘mother tongue’ in his first and second years at primary school. Wagenbach says of Franz Kafka:

He was the only one [of the Prague-based German authors] who spoke and wrote Czech almost flawlessly, who had grown up in the middle of the old town, on the edge of the ghetto quarter, then still an architectonic unity. Kafka never lost this close link to the Czech people, never forgot this atmosphere of his youth.55

Goldstücker adds that in his ‘Character sketch of small literatures’, which is concerned with Czech and Yiddish literature, Kafka looked back at the popular intellectual legacy of his forefathers.56 Specifically, Goldstücker meant his Czech intellectual legacy, even though Kafka was actually more concerned – the mentioned text draws on Yitzchak Löwy – with the Jewish legacy.

The transformation of the representative of the ‘Prague German-Jewish bourgeoisie’57 – this label was Kafka’s doom, ideologically speaking, during the Stalin era – into a son of the ‘Czech-Jewish rural proletariat’ was thus complete, while the Jewish aspect was pushed into the background. But how closely is this instrumentalised construction to actual reality? On this point the otherwise usually surreal Hugo Siebenschein sticks fairly close to the facts in his remarks on Kafka. Regarding language, for instance, he mentions that Hermann Kafka spoke ‘perfect German’ and that both languages (German and Czech) were ‘equally satisfying and equally interchangeable means of communication’.58 In the Czech original, Siebenschein’s formulation ‘lhostejný’ (indifferent) makes clear that the interchangeability is also to be understood beyond Czech and German national identity. Other retouched details could also have done with being corrected in the same way.59

In turn, Hartmut Binder’s German-centric account of Franz Kafka in his biographical overview of the author and his family omits ‘Czech’ elements and in doing so appropriates Kafka for German-language culture. Binder applies the label ‘German Jew’ to Hermann Kafka, for example when he says of Kafka’s mother Julie: ‘she is also to be included in the German-Jewish population of Bohemia’.60 Here we are to understand ‘also’ as meaning just like Kafka’s father. Elsewhere, on Kafka’s father Binder writes: ‘His mother tongue was German: the gravestone of Jakob Kafka also has a German inscription alongside the one in Hebrew’.61 Binder also refers to the family’s German tradition, which he sees confirmed in the names of Jakob Kafka’s children

(Philip/Philipp, Anna, Heinrich, Hermann, Julie, Ludwig) or those of Hermann Kafka (Franz, Georg, Heinrich, Gabriela, Valerie, Ottilie), ignoring the broader context of naming discussed in the next chapter. He also points out that German was the language of instruction at Jewish schools, which no doubt was also the case in Osek. Finally, Binder’s explanation of the etymology of the surname ‘Kafka’ is different; he sees it as deriving from ‘Kov-ke’, the supposed Low German diminutive form of the name  (Yaakov), which is said to have been used by Ashkenazic Jews.62

(Yaakov), which is said to have been used by Ashkenazic Jews.62

Of course, such categories imposed from the outside or projected outwards have very little to do with the reality. Wagenbach regards Hermann Kafka as a ‘Czech Jew’ on the basis of his supposedly preferred language whilst Kafka’s mother is seen as a ‘German Jew’ on the basis of her language. However, of the texts that have survived, Hermann Kafka’s papers contain only German writings,63 whilst there is evidence that Julie Kafka also wrote letters in Czech to staff which were – phonetically at least – in flawless Czech. Furthermore, in her letters, Julie Kafka addressed her daughter, with whom she otherwise wrote German letters, using Czech names such as ‘Otilko’, ‘Ellinko’.64

Goldstücker’s ‘grounding’ of Kafka and – through this – his territorial, social and national appropriation of Kafka as ‘one of us’ reached its height in October 1963 when he presented the writer as ‘attached to his homeland and his people’ in an article in Literární noviny:

For us in Czechoslovakia he [= Kafka] means more. He was born in Prague; his entire life and his entire oeuvre are bound up with our capital city and our land. [. . .] Memories and stories of Kafka in which truth and fiction are intertwined circulate amongst the simple people of Prague’s old town. [. . .] his work [. . .] contains the imprint of our worries.65

This remark appeared in an essay written in response to the attack by his ‘comrade’ Kurella and it thus needs to be seen in the wider context of the debate around estrangement. Opinions were divided on whether estrangement was merely to be viewed as a temporary historical phenomenon in bourgeois society, as the representatives of German Studies in the German Democratic Republic were keen to understand it, or whether this concept could be applied elsewhere, as was claimed not only by the Czechoslovak Marxist literary scholars who took part in the Kafka conference but also by Ernst Fischer and Roger Garaudy.66 This political engagement of Marxist literary studies led to a transgression of boundaries of scholarship which led to an aversion against Kafka amongst Marxist ideologues and regime yes-men, as is mentioned in Zábrana’s diary. Criticism of Kafka also drew on non-literary arguments. For example, in the key Czech journal for theory and history of literature Česká literatura (Czech Literature) Vítězslav Rzounek compared Kafka and Jaroslav Hašek and rejected Kafka on the basis of biographical arguments for being decadent, for unlike Hašek, who participated in the revolution, Kafka had apparently opposed the revolution.67 This is the kind of language that we are familiar with from the 1950s and which was rejected by Sartre. Yet in his article, quoted above, Goldstücker’s piece is far from being merely an attempt at self-justification in the face of the attacks by the ‘comrade’ Kurella.68 Rather, it presents an idea that is reinforced through the Czech press and culminates in Kafka’s transformation into a ‘Czech’ author. Goldstücker had earlier called for a territorial, social and national ‘grounding’ of Kafka in the February issue of Literární noviny, cited earlier,69 and in doing so had chalked out the development of Kafka’s reception in 1963.

In his contextualisation of Kafka’s works, Goldstücker also saw an opportunity to curb the proliferation of Kafka scholarship and to ‘surmount the ambiguity’ of the various interpretations of Franz Kafka. He thus precluded the possibility that the appeal of the author might actually lie precisely in his ‘multiple voices’, as is argued by Benno Wagner, who also writes of the ‘poetic shorthand’ by which Kafka ‘records’ the plurality of contemporary discourses in his work.70 Goldstücker also defended his vague idea of the ‘grounding’ of Kafka’s writings, which met with a critical response from Ivo Fleischmann in Literární noviny in March 1963.71 Drawing on Max Brod, Fleischmann described Kafka as a religious, metaphysical, transcendental writer who represents the life into which we are thrown as a trial that we lead with ourselves and with God and in which we – since of course we have to die – are always the losers. In true Marxist fashion, Goldstücker’s response warned people against the illusion that

an artistic work and its creator can be understood in their entirety without considering alongside the work the external, personal, social, historical circumstances in which the artist lived and out of which he created his art.72

This kind of ‘grounding’, that is, the localisation of Kafka in a Prague and Czech context, which supersedes the Jewish aspects – as in the polemic with Fleischmann – was also Goldstücker’s main concern at the Liblice conference. His insistence on a Prague-based interpretation is clear in the circumscription ‘from the Prague perspective’ in the title of the conference proceedings. The Prague perspective, which consisted in the biographical localisation of Kafka, also echoed in the personal memory recounted by the Communist ‘national artist’ Marie Majerová during her opening speech:

He spoke Czech and wrote in German; he often spent time with us although he remained distant. But as a Prague man he was one of us, a native of the old Prague lanes [. . .], a connoisseur of Czech literature. Whilst we, however, wandered in the still fresh traces of Neruda, he, so to speak, meandered in the 500 hundred-year-old footprints of Rabbi Lowe.73

Tellingly, in her speech the Jewish aspect of Kafka’s biography was mentioned in passing, only to be – as was largely the case in the other conference papers – superseded immediately, as if it was only the rhetorical anchoring of Kafka amongst the Czech people and Czech national literature (Jan Neruda) that counted. Then, after two further opening speeches (Eduard Goldstücker, Pavel Reiman),74 it was Eduard Goldstücker’s turn with his Marxist ‘grounding’ of Kafka in his paper ‘Franz Kafka from the Prague perspective’ in which he picked up on the aforementioned biographical topoi. He argued, among other things, that Kafka could only be fully understood by taking Prague as the starting point; that the Prague context forms the base out of which Kafka’s works grow; that the author seeks out a connection with his people, to which his work also bears witness. He repeatedly declared his conviction that the ‘Prague perspective’ would prove that ‘answers to some questions relating to Kafka’s life and oeuvre could in fact be best provided by taking Prague as the starting point’.75 He continued by arguing that Kafka’s ‘Prague-related life issues’ were reflected in his work and, accordingly, that only the understanding of the wider historical-social context could form a steady ‘base’ for the understanding of Kafka’s work, that is of the ‘superstructure’. In Goldstücker’s terms, it was precisely the ‘fundamental scholarly [i.e. Marxist] illumination of the issues [. . .] encapsulated in the caption Kafka and Prague’ that was the ‘key’ to Kafka.76 This ‘base’ approach gave precedence to biographical and social factors over the ‘superstructure’ of his texts.

Goldstücker’s paper was followed by František Kautman’s presentation ‘Franz Kafka and Czech Literature’, which listed the affinities between Kafka’s oeuvre and Czech literature and culture, but rated these rather as coincidental and fleeting.77 This notwithstanding, he too was of the opinion that Kafka’s oeuvre was inconceivable without the Czech context. The article published in Literární noviny also judged these two plenary lectures to be of central importance.78

In this context the opinion of Václav Černý is particularly worth mentioning. Černý, who had begun to write about Kafka as early as the 1940s, saw in Kafka a forerunner of the existentialists and, following Sartre’s impulse, took a philosophical approach to Kafka.79 Tellingly, he was not invited to the Liblice conference where, it seemed, the ‘comrades’ preferred to stick to themselves with their ‘grounding’ of Kafka.80 Nevertheless, the Liblice conference could hardly escape anyone’s notice, and he referred to it in the following way:

Here, the number of reviews began to rise dramatically in 1963, that is, at the time of the third Writers’ Congress and of the largely unsuccessful international conference on Kafka in Liblice. Goldstücker was quite clumsy in his endeavours at the conference to bang Kafka into the size and shape of the social, if not socialist, poet. He had only been released from prison a short time before and the regime compensated him by securing him a chair at Charles University. Goldstücker did what he could and was also prepared to do what was not allowed to be done for others. Yet Kafka had been sanctioned – a sign of the changing times!81

Sartre’s foray into the reading of a literary work and his drive to liberate culture from the clutches of politics failed to make real inroads at the Liblice conference; Kafka’s selectively narrated biography continued to take precedence in the endeavour to ground him in a local, social and national context. Nevertheless, his writings did get through to readers, even if they failed to secure a central position in the interest of literary scholars.

CZECH READINGS OF CZECH TEXTS

Alongside Kautman’s paper, which under the circumstances of the period was a remarkable pioneering achievement, it was the first publications of Kafka’s Czech letters in 1963, fragmentary as they were, which broke new ground for Kafka scholarship.82 The first widely available book edition of Kafka’s letters to his family and of his office writings, which includes Kafka’s Czech texts published in 1963 in Czechoslovakia, were only published ten years later in Germany.83 On the back of the 1963 publications Prague had an advantage in Kafka-related knowledge and scholarship. But despite what is to be gleaned from Eduard Goldstücker’s polemical articles, these letters hardly made a solid case for the ‘single correct interpretation’ of Kafka’s ambiguous writings; nor did they justify the claim that Kafka could only be interpreted ‘from the Prague perspective’. Also the fact that Kafka was proficient in Czech was by no means new knowledge. Since, however, prior to the publication of Kafka’s Czech texts in 1963 people had had to rely on witnesses rather than textual evidence to underpin their claims, this had left a lot of room for the imagination.

So it was, for example, in 1947, that Hugo Siebenschein in the otherwise respectable monograph Franz Kafka and Prague was able to claim somewhat surreally that Franz Kafka, whom he categorised as a ‘surreal writer’, sang only in Czech:

The language of his political friends was Czech; it was only in Czech that he could be as carefree and curious as a child; it was only in Czech that he sang. More sceptical friends were surprised when they saw him amongst the crowd of Czech demonstrators singing nationalist, Sokol and Socialist songs. He was frequently caught singing at the top of his lungs ‘Hey, Slavs’, pale and excited, apparently oblivious to everything around him, his timid eyes aglow with enthusiasm.84

Another and no less problematic contemporary witness of Kafka and his relationship with his milieu – including his Czech setting – emerged in 1951 in the figure of Gustav Janouch.85 A few years later, in 1958, Klaus Wagenbach’s influential monograph was published in Germany which, drawing on the primary Prague sources, depicted Kafka’s anarchism as well as, with reference to Hermann Kafka, the Czech blood running through Kafka’s veins.86

The edition of Kafka’s Czech texts did not just mean the next forays in this direction, however; they also brought new, unknown sources to light. O. Beneš and P. Lecler, translators of these sources into French, expressed the impact of these letters with impressive precision in their decision to title their translation ‘Kafka inconnu’ (Unknown Kafka).87 Kafka, and not his literary writings, takes centre stage here, and it is the desire to discover the unknown and even – in the Czechoslovak context – taboo Kafka which drives this obsession with revelation. It is also remarkable that both ‘discoveries’ of Kafka’s Czech texts which show Kafka ‘from the Prague perspective’, and thus reinforce the impact of the Liblice conference, were made public independently of the conference, namely in the journal Plamen and the museum’s journal. At the Liblice conference Josef Čermák reported on the ‘unknown Kafka papers’ – that is, on Kafka’s letters to Ottla and his family. In the conference proceedings which were published in Czech in the very same year of the conference, Čermák referred explicitly to the publication of the letters in the July edition of Plamen,88 but they were not reprinted in the conference volume. It was only after 1989 that these writings were published as part of the critical edition of Kafka’s works.89 This makes their publication from 1963 so important because they seemingly support the ‘grounding’ of Kafka.

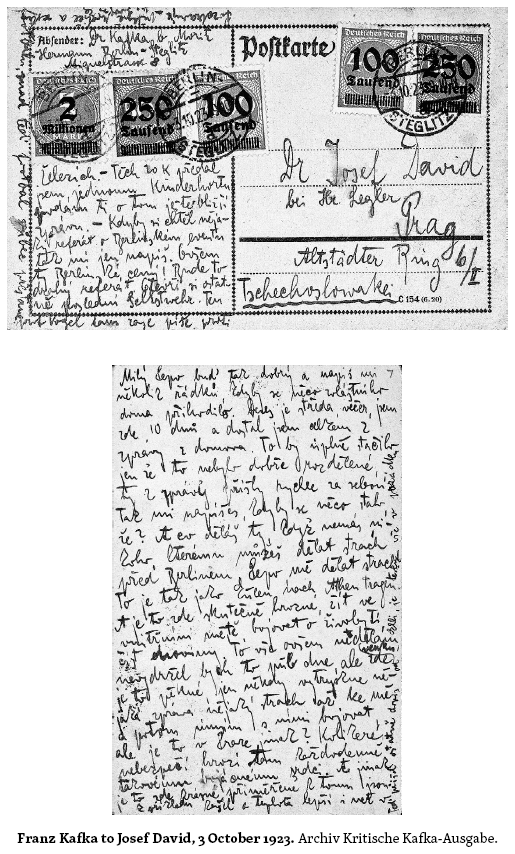

At the same time we are dealing here – as is often the case with Kafka – with more than one paradox. Although the editing of the unknown letters in Plamen makes clear that Franz Kafka asked Ottla and her Czech husband Josef David to translate his letters to the Workmen’s Accident Insurance Company from German into Czech, the private letters to Ottla, née Kafka, and Josef David published in 1963, which made a considerable contribution to the myth of Kafka’s affinity with Czech language, culture and the people, because they were written in Czech. Then, the publication provided the Czech public and thus also Czech Germanists with proof that in these non-translated letters to his relatives Kafka’s written (and spoken) Czech was largely impeccable. It was not too great a leap of imagination to claim that he was inextricably connected with Czech language and culture and thus was best understood ‘from the Prague perspective’.

In reality, however, Kafka’s Czech was by no means as flawless as this edition of his letters led readers to believe. On four small A5-pages of the Czech text, there are 53 corrections to the original which present Kafka’s Czech in the printed version in a more positive light. Here are just a few examples based on a comparison of the manuscripts held in the Bodleian Library (Oxford):90 in the Czech edition from 1963 zúčastnil instead of the original zůčastnil, lyžařský instead of lyžarský, náděje instead of nádeje, [ty] jsi instead of [ty] si, hebrejsky instead of Hebrejský, totiž instead of totíž, oprav jí to instead of oprav ji to, nepříjemné instead of nepřijemné, lékařské instead of lékarské, děkuji instead of [já] děkují, nabídku instead of nábídku, půjdeš instead of půjdes, večer instead of večér, napíšeš instead of napíšes, nemáš instead of nemás, ke mně instead of ke mě, s nimi instead of s ními, ještě instead of ješte, jsi chtěl instead of si chtěl, o berlínském instead of o Berlinském, berlínské ceny instead of Berlinské cený, etc.

The most significant example for this edition is the correction of an error in Kafka’s use of the aspect, which is the best indicator of native or near-native proficiency in Czech. The Czech edition corrects the original ‘buď bude třeba abych se dále léčil totiž buď bude nádeje že bych se mohl ještě dále vyléčit’ (on one hand it will be necessary to stay in the sanatorium which means, on one hand there is a hope that I might further fully recover) in ‘buď bude třeba abych se dále léčil totiž buď bude náděje že bych se mohl ještě dále léčit’91 (on one hand it will be necessary to stay in the sanatorium, which means, on one hand there is a hope that I might recover further), because the original seems to be ‘incorrect’: the perfective vyléčit (fully recover) is in opposition to dále (further).

It was probably such unknown corrections that enabled Kafka to be seen as completely bilingual and encouraged people to cling to the belief in Kafka’s inner affinity with the Czech language.92 Thus, for example, Jaromír Loužil, editor of Kafka’s official letters to the Workmen’s Accident Insurance Company drafted or translated by Kafka’s relatives, claimed, in spite of his knowledge and somewhat prematurely, that they prove his almost complete proficiency in the Czech language; according to Loužil we are most certainly dealing with much more than the version of Czech as we know it spoken by Austrian lawyers.93 Yet with a few exceptions, these texts can hardly be considered authentic Czech writings by Kafka in view of the fact that they were either drafted and proved for Kafka or translated from German into Czech.94

References to Kafka’s affinity with the ‘Czech element’ also came from elsewhere. I am referring here to the memoirs of Anna Pouzarová, a Czech woman who as a 21 year old worked for the Kafka family as the governess of Kafka’s sisters. These were published in 1964 in the journal Plamen (Flame) and the newspaper Práce (Labour) and were given a distinct slant by the editor’s commentary.95 The commentary tells the story of a little known love between the ‘attractive and slim’ Czech woman and the two-years-younger Kafka who would always urge Anna to read out loud to his sisters from The Grandmother by the Czech national writer Božena Němcová. In a single swoop, then, we have here the national appropriation of Kafka, not just in a linguistic but also in a literary and erotic sense.96 More props to support this appropriation could have been garnered from letters to Milena, in which fragments of Czech from Milena’s Czech letters flow into Kafka’s German letters and in which there are scattered references to Czech authors (and which were published in 1966 in a popular edition).97 Pavel Reiman did just this at the end of his afterword to the Czech edition of The Trial; his otherwise objective afterword ends by expressing his joy that this Franz Kafka novel has now been published in ‘the language of his Milena Jesenská’.98 The point is, however, that in the case of Anna Pouzarová we are dealing with a private matter and in Milena Jesenská’s case with private letters, and not with literary texts. Although the reference to Němcová is important, it remains the case that in the 1960s – apart from the identification of such moments of affinity commendably compiled by Kautman99 – there was a dearth of serious analyses of Kafka’s writings that would and could show this side of Kafka ‘from the Prague perspective’ on the basis of his literary texts. Goldstücker’s call for a ‘grounding’ of Kafka and his interpretative approach to Kafka ‘from the Prague perspective’ remained entrenched in biographical and sociological arguments.

A further problem arises in connection with this. The key term ‘Prague’ in ‘from the Prague perspective’ was not only bound up very strongly in the context of the Liblice conference but also in the press, which endorsed the arguments of the Liblice conference,100 with the local context and, accordingly, also with Czech themes and a ‘Czech perspective’. This is very clear in the Goldstücker quotation, cited earlier, which I shall repeat in these closing remarks in order to highlight his appropriation of Kafka as ‘one of us’ that emerges here:

For us in Czechoslovakia he [= Kafka] means more. He was born in Prague; his entire life and his entire oeuvre are bound up with our capital city and our land.101

If we consider the actual proportion of Czech to Jewish elements in Kafka’s real life, his circle of friends, correspondence, reading and writing, it becomes clear that the co-opting of the term ‘Prague’ in the motto ‘from the Prague perspective’ for the local social context as well as Czech national literature and language corresponds with a partial omission of the Jewish dimension of Kafka’s biography and oeuvre. Nevertheless, the Liblice conference of 1963 may well be a part of Bohemian culture’s return to its Jewish roots. For example, there followed in 1964 the renaming of the Památník národního utrpení (Monument of national suffering) to Památník Terezín (Terezín Memorial) and it was during this time that plans for a ghetto museum in Terezín were forged. This, however, has little to do with Kafka’s texts and the Liblice conference of 1963 followed another path.

1 See Josef Čermák, Die Kafka-Rezeption in Böhmen (1913–1949) (Kafka’s reception in Bohemia 1913–1949). In: Kurt Krolop – Hans Dieter Zimmermann (eds), Kafka und Prag (Kafka and Prague). Berlin, New York: de Gruyter 1994, pp. 217–237; Josef Čermák, Die Kafka-Rezeption in Böhmen (1913–1949) (Kafka’s reception in Bohemia 1913–1949). Germanoslavica 1 (1994), pp. 1–2, pp. 127–144; and Josef Čermák, Recepce Franze Kafky v Čechách (1913–1963) (Franz Kafka’s reception in Bohemia (1913–1963). In: Kafkova zpráva o světě (Kafka’s Report on the World). Prague: Nakladatelství Franze Kafky 2000, pp. 14–36.

2 See Josef Čermák, Česká kultura a Franz Kafka: Recepce Kafkova díla v letech 1920–1948 (Czech culture and Franz Kafka: Reception of Kafka’s work 1920–1948). Česká literatura 16 (1968), pp. 463–473.

3 See Franz Kafka, Neznámé dopisy Franze Kafky (Unknown letters by Franz Kafka). Translation by Aloys Skoumal. Introduced by Jiří Hájek. Plamen 5 (1963), No. 6, pp. 84–94; Jaromír Loužil, Dopisy Franze Kafky Dělnické úrazové pojišťovně pro Čechy v Praze (Franz Kafka’s letters to the Worker’s Accident Insurance Company). Sborník Národního muzea v Praze, Row C, Literary history 8 (1963), No. 2, pp. 57–83. The Czech passages in Kafka’s Briefe an Milena are mainly quotations from Milena’s letters. See Franz Kafka, Briefe an Milena (The Letters to Milena). Frankfurt am Main: Fischer 1952.

4 These categories persisted, resulting in the view of Kafka as representative of the ‘Prague German-Jewish bourgeoisie’. See Pavel Reiman, ‘Proces’ Franze Kafky (Franz Kafka’s The Trial). In: Franz Kafka, Proces (The Trial). Prague: Československý spisovatel 1958, pp. 207–225, p. 211.

5 See Eduard Goldstücker – František Kautman – Pavel Reiman (eds), Franz Kafka: liblická konference 1963 (Franz Kafka: Liblice Conference 1963). Prague: ČSAV 1963; Eduard Goldstücker – František Kautman – Paul Reiman (eds), Franz Kafka aus Prager Sicht 1963 (Franz Kafka from the Prague Perspective 1963). Prague: ČSAV 1965.

6 The question of the ‘initiation’ of this conference is contentious; nevertheless, the conference’s organisation highlights the central role of Eduard Goldstücker and Pavel/Paul Reiman/Reimann. The conference was organised by the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, Charles University and the Czechoslovak Writers’ Guild in Liblice Castle on 27 and 28 May 1963. Over twenty speakers, from Czechoslovakia, the GDR, Poland, Hungary, Yugoslavia, France (Roger Garaudy) and Austria (Ernst Fischer) participated in the conference. The following authors appear in the conference proceedings: O. F. Babler, Josef Čermák, Zdeněk Eis, Dagmar Eisnerová, Ernst Fischer, Pavel Trost, Ivo Fleischmann, Norbert Frýd, Roger Garaudy, Jiří Hájek, Klaus Hermsdorf, František Kautman, Jenö Krammer, Alexej Kusák, Dušan Ludvík, Josef B. Michl, Werner Mittenzwei, Pavel Petr, Jiřina Popelová, Petr Rákos, Pavel Reiman, Helmut Richter, Ernst Schumacher, Ivan Sviták, Pavel Trost and Antonín Václavík.

For more see Michal Reiman, Die Kafka-Konferenz von 1963 (The Kafka conference of 1963). In: Michaela Marek – Dušan Kováč – Jiří Pešek – Roman Prahl (eds), Kultur als Vehikel und als Opponent politischer Absichten. Kulturkontakte zwischen Deutschen, Tschechen und Slowaken von der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts bis in die 1980er Jahre (Culture as Medium and Opponent of Political Programs: Cultural Contact between Germans, Czechs and Slovaks from the middle of 19th Century to the 1980s). Essen: Klartext 2010, pp. 107–113, or Ines Koeltzsch, Liblice. In: Dan Diner (ed.), Enzyklopädie jüdischer Geschichte und Kultur (Encyclopaedia of Jewish History and Culture). Vol. 3 (He – Lu). Stuttgart, Weimar: Metzler 2012, pp. 511–515.

7 For more on the terminology used here see Petr A. Bílek, Obraz Boženy Němcové – pár poznámek k jeho emblematické funkci (The image of Božena Němcová – some remarks on its emblematic function). In: Karel Piorecký (ed.), Božena Němcová a její Babička (Božena Němcová and her Babička). Prague: Ústav pro českou literaturu 2006, pp. 11–23.

8 See Vladimir V. Kusin, The Intellectual Origins of the Prague Spring. The Development of Reformist Ideas in Czechoslovakia 1956–1967. Cambridge (MA): Cambridge University Press 2002.

9 See Eduard Goldstücker, Prozesse. Erfahrungen eines Mitteleuropäers (Trials: Experiences of a Central European). Munich: Knaus 1989; Eduard Goldstücker, Vzpomínky (Memoirs) Vol. 2: 1945– 1968. Prague: G plus G 2005; Alexej Kusák, Tance kolem Kafky: Liblická konference 1963 – vzpomínky a dokumenty po 40 letech (The Dance around Kafka: the Liblice Conference of 1963 – Memories and Papers 40 Years on). Prague: Akropolis 2003.

10 See e.g. Alfred Kurella, Jaro, vlaštovky a Franz Kafka (Spring, the swallows and Franz Kafka). Literární noviny 12 (1963), No. 40, p. 8, and Ernst Fischer, Jaro, vlaštovky a Franz Kafka (Spring, the swallows and Franz Kafka). Literární noviny 12 (1963), No. 41, p. 9. See further Čermák, Recepce Franze Kafky, p. 28, which contains the revealing reference to Howard Fast’s Czech edition. See Howard Fast, Literatura a skutečnost (Literature and Reality). Translation by Zd. Kirschner and Jaroslav Bílý. Prague: Svoboda 1951. Fast also sees Kafka not as a swallow but a repugnant bird (‘Kafka’ literally means jackdaw) which sits atop ‘the cultural dungheap of reaction’.

11 Franz Kafka to Ottla, 10 July 1914. – See Franz Kafka, Letters to Friends, Family, and Editors. New York: Schocken Books 1977, p. 109.

12 Jan Zábrana, Celý život: Výbor z deníků 5. listopadu. 1976 – července 1984 (A Whole Life: Selected Passages from the Diaries, 5 November 1976 – July 1984). Vol. 2. Prague: Torst 1992, p. 567.

13 Zábrana, Celý život, p. 886.

14 Franz Kafka, Doupě (The burrow). Světová literatura 3 (1957), pp. 132–153; Pavel Eisner, Franz Kafka. Světová literatura 3 (1957), pp. 109–129; Pavel Eisner, Německá literatura na půdě ČSR. Od r. 1848 do našich dnů (German literature on Czechoslovak territory. From 1848 to the present day). In: Československá vlastivěda (Encyclopaedic Information on Czechoslovakia). Vol. VII: Písemnictví (Letters). Prague: Sfinx 1933, pp. 325–277.

15 Čermák, Recepce Franze Kafky, p. 28.

16 Franz Kafka, Proces (The Trial). Translation and afterword by Pavel Eisner. Prague: Československý spisovatel 1958; with commentary by Ján Rozner, Případ Kafka? Nad českým vydáním Procesu (The case of Kafka? On the Czech edition of The Trial). Slovenské pohľady 75 (1959), No. 2, pp. 125–140.

17 Ivan Dubský – Mojmír Hrbek, Kafkův Proces (Kafka’s The Trial). Květen 3 (1958), pp. 620–623; Oleg Sus, Kafka – zmatení jazyků (Kafka – the confusion of tongues). Host do domu 6 (1959), pp. 139–140; Pavel Reiman, Společenská problematika v Kafkových románech (On the social issues in Kafka’s novels). Nová mysl 1 (1958), pp. 52–63; Jiří Hájek, Spor o Franze Kafku (The dispute over Franz Kafka). Tvorba 24, 8. 1. 1959, No. 2, pp. 31–32.

18 Čestmír Jeřábek, Jubileum pražského básníka (Anniversary of the Prague writer). Host do domu 5 (1958), pp. 334–335; Čestmír Jeřábek, Kafkův Proces česky (Kafka’s The Trial in Czech). Host do domu 5 (1958), pp. 373–374. See Maria Luise Caputo-Mayr – Julius Michael Herz, Franz Kafka: Internationale Bibliographie. Vol. 1–2. Munich: De Gruyter/Saur 1997 & 2000, here vol. 2, p. 255.

19 Oskar Kosta, Hledání a bloudění Franze Kafky (The searching and wandering of Franz Kafka). Nový život 10 (1958), pp. 784–786; Josef Svoboda, Bez víry? (Without faith?). Křesťanská revue 25 (1958), pp. 283–285.

20 The illustrated volume by Frynta published in the interim was only intended for a non-Czech readership. See Emanuel Frynta, Franz Kafka lebte in Prag (Franz Kafka Lived in Prague). With photographs by Jan Lukas. Translation into German by Lotte Elsner. Prague: Artia 1960.

21 Eduard Goldstücker, Předtucha zániku: K profilu pražské německé poezie před půlstoletím (Premonition of doom: On the profile of German poetry in Prague 50 years ago). Plamen 2 (1960), pp. 92–96; Růžena Grebeníčková, Gogolovy ‘metamorphosis’ na Západě (Gogol’s ‘metamorphosis’ in the West). Plamen 2 (1960), pp. 126–128.

22 Starting with Ivan Dubský – Mojmír Hrbek, O Franzi Kafkovi (On Franz Kafka). Nový život 8 (1956), pp. 415–435.

23 See Hana Pichová, The Lineup for Meat: The Stalin Statue in Prague. PMLA (Journal of Modern Language Association of America) 123 (2008), 3, pp. 614–630.

24 Franz Kafka, Amerika (The Man who Disappeared). Czech translation by Dagmar Eisnerová. Prague: SNKLU 1962; Pavel Reiman, Úvod (Foreword). In: Franz Kafka, Amerika. Prague: SNKLU 1962, pp. 7–23.

25 Ivan Dubský, Kafkova Amerika (Kafka’s Amerika). Kultura 6 (1962), 12, p. 4; Ivan Dubský, Amerika aneb Nezvěstný (Kafka’s Amerika or The Man who Disappeared). Host do domu 9 (1962), 4, p. 181f.; Ivo Fleischmann, Kafkova Amerika (Kafka’s Amerika). Literární noviny 11 (1962), No. 16, pp. 368–369; Eduard Goldstücker, Kafkův ‘Topič’ (Kafka’s ‘The Stoker’). Tvorba 27 (1962), No. 16, pp. 368–369; Gm [= Pavel Grym], Kafkův hrdina v labyrintu světa (Kafka’s hero in the labyrinth of the world). Lidová demokracie, 16.2.1962, p. 3.

26 Zdeněk Kožmín, Marxistická monografie o Kafkovi (Marxist monograph on Kafka). Host do domu 7 (1962), pp. 223–225; Agneša Kalinová, Kafka v Bergamu (Kafka in Bergamo). Literární noviny 11 (1962), No. 40, p. 8; Zf, O Kafkovi trochu jinak (Harry Järve’s bibliography of Kafka scholarship). Lidová demokracie, 8.4.1962, p. 5.

27 Franz Kafka, Dopis otci (Letter to his Father). Světová literatura 7 (1962), No. 6, pp. 84–112. Translation by Dagmar Eisnerová and Pavel Eisner, introduced by Klaus Hermsdorf.

28 See Jean-Paul Sartre, La démilitarisation de la culture: Extrait du discours à Moscou devant le Congrès mondial pour le désarmement générale et la paix. France-Observateur, 17.7.1962, pp. 12–14; Stephan Hermlin, Die Abrüstung der Kultur. Rede auf dem Weltfriedenkongress in Moskau. (The demilitarization of culture: Speech for the world peace conference in Moskau). Sinn und Form 14 (1962), pp. 805–815.

29 Veronika Tuckerová deals with the reception of Franz Kafka between the East and the West during the Cold War. I was unable to get hold of her dissertation. Veronila Tuckerová, Reading Kafka in Prague: The Reception of Franz Kafka between the East and the West during the Cold War. New York: Columbia University 2012.

30 Franz Kafka, Proměna (The Metamorphosis). Translation by Zbyněk Sekal and afterword by Josef Čermák. Prague: SNKLU 1963.

31 See Marek Nekula, Einblendung und Ausblendung: Tschechoslowakische Kafka-Rezeption und Erstveröffentlichungen von Kafkas tschechischen Texten (From the shadow into light: The Czechoslovak reception of Franz Kafka and the first publication of his Czech texts). In: Steffen Höhne – Ludger Udolph (eds), Franz Kafka – Wirkung, Wirkungsverhinderung (Franz Kafka: Reception and Reception Blocks). Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau 2014, pp. 61–91. This paper contains a list of sources which is based on my own research conducted with the help of the Bibliografický katalog ČSSR – články v českých časopisech, and related research by Jiskra Jindrová from the bibliographical department of the Czech National Library in Prague, and also draws slightly on Caputo-Mayr – Herz, Franz Kafka: Internationale Bibliographie. In my endeavour to document this ‘flood’ of sources, the bibliography has become very long; only some of these texts are quoted in this chapter.

32 Fischer, Jaro, vlaštovky a Franz Kafka.

33 Eduard Goldstücker, Jak je to s Franzem Kafkou? (How do things stand with Franz Kafka?) Literární noviny 12 (1963), No. 7, p. 4; Eduard Goldstücker, Na téma Franz Kafka. Články a studie (On the Subject of Franz Kafka: Essays and Papers). Prague: Československý spisovatel 1964, p. 62. See also Eduard Goldstücker, Vyděděnci a temný obraz světa (Outcasts and their dark image of the world). Plamen 3 (1961), No. 10, pp. 66–69.

34 On the show trial see for example Goldstücker, Prozesse, or Koeltzsch, Liblice. In 1956 Goldstücker became a lecturer at Charles University. He was completely rehabilitated and appointed professor in 1963.

35 See e.g. Jiří Hájek, Kafka a marxistické literární myšlení (Kafka and Marxist literary thought). Plamen 5 (1963), No. 7, pp. 131–132, as well as A. Petřina, Jako v Kafkově ‘Procesu’ (As in Kafka’s The Trial). Rudé právo 43, 10.8.1963, No. 219, p. 3.

36 Dr. M. K. [= Miroslav Kaňák], Ztracený a znovu nalezený (Lost and found). Český zápas 46 (1963), No. 34–35, p. 8.

37 Article on the exhibition in Literární noviny 12 (1963), No. 23, p. 13. The reflection of Kafka in terms of ‘return’ is present also in Ivan Dubský, Návrat Franze Kafky (The return of Franz Kafka). Kulturní tvorba 1 (1963), No. 26, p. 8; and Zdeněk Pešat, Kafkův návrat domů a literární věda (Kafka’s homecoming and literary studies). Literární noviny 12 (1963), No. 17, p. 5.

38 See Eduard Goldstücker, Lidské poselství hledajícího člověka (Human legacy in search of people). Rudé právo, 3.7.1963, p. 5; Svatoslav Svoboda, Franz Kafka. Mladá fronta, 3.7.1963, p. 5; Josef Čermák, Franz Kafka, umělec naší doby (F.K., Artist of our age). Práce, 3.7.1963, p. 4; Vlastimil Vrabec, Fantastický svět Franze Kafky (The fantastical world of Franz Kafka). Svobodné slovo, 2.7.1963, p. 3; Miloslav Bureš, Franz Kafka u nás (Franz Kafka here with us, a list of the old and planned translations). Svobodné slovo, 9.7.1963, p. 3; Věra Poppova, Výročí Franze Kafky (Franz Kafka’s anniversary). Lidová demokracie, 3.7.1963, p. 3.

39 See Vl. Moulíková, K nedožitým osmdesátinám Franze Kafky (On what would have been Franz Kafka’s 80th birthday). Vlasta 17 (1963), No. 34, p. 6 f.; Franz Kafka, Poselství Franze Kafky (Legacy of Franz Kafka). With translations of ‘First sorrow’ and ‘Poseidon’ by Jiří Gruša. Mladý svět 5 (1963), No. 27, pp. 10–11. See also F. R. Kraus, K 80. narozeninám Franze Kafky (On Franz Kafka’s 80th birthday). Věstník židovských náboženských obcí v Československu 25 (1963), No. 7, p. 6.

40 Louis Fürnberg, Život a smrt Franze Kafky (The Life and Death of Franz Kafka). Translation by Valter Feldstein. Plamen 5 (1963), No. 7, p. 108.

41 Ivan Diviš, Franz Kafka. Literární noviny 12 (1963), No. 27, p. 7.

42 See Eduard Goldstücker, Über Franz Kafka aus der Prager Sicht (On Franz Kafka from the Prague perspective). Translation by Kurt Krolop In: Eduard Goldstücker – František Kautman – Paul Reimann (eds), Franz Kafka aus Prager Sicht 1963 (Franz Kafka from the Prague Perspective 1963). Prague: ČSAV 1965, pp. 23–43, p. 32.

43 Goldstücker draws a direct connection between Kafka and ‘utopian Socialism’, and at the same time also establishes an analogy between Karl Rossman, the Stoker and the bosses (captain, shipping company) on the one hand and Kafka, customers of his insurance company and the management of his insurance company on the other. Similarly, he understands the ‘surveyor’ in accordance with the Marxist idea of ‘land division’ as a character preparing to carry out the ‘distribution of property’. Goldstücker, Über Franz Kafka aus der Prager Sicht, 37, 43. See also Eduard Goldstücker, Kafkas ‘Der Heizer’. Versuch einer Interpretation (Kafka’s ‘The Stoker’: An attempt at an interpretation). Germanistica Pragensia 2 (1964), pp. 49–64, as well as Eduard Goldstücker, Doslov (Afterword). In: Franz Kafka, Zámek (The Castle). Prague: Mladá fronta 1964, pp. 306–313.

44 Goldstücker. Na téma Franz Kafka, p. 67.

45 On modernity see Silvio Vietta, Ästhetik der Moderne: Literatur und Bild (Aesthetics of the Modern: Literature and Image). Munich: Fink 2001. On the treatment of discourses see Andreas Kilcher, Kafkas Proteus: Verhandlungen mit Odradek (Kafka’s Proteus: Negotiation with Odradek). In: Irmgard M. Wirtz (ed.), Kafka verschrieben (Committed to Kafka). Göttingen, Zürich: Wallstein 2010, pp. 97–116; Marek Nekula, Kafkas ‘organische’ Sprache: Sprachdiskurs als Kampfdiskurs (Kafka’s organic language: Language discourse as struggle discourse). In: Manfred Engel – Ritchie Robertson (eds), Kafka, Prag und der Erste Weltkrieg. Kafka, Prague, and the First World War. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann 2012, pp. 237–256.

46 Jan Grossman, Kafkova divadelnost? (Kafka’s theatricality?). Divadlo 9 (1964), pp. 1–17.

47 Goldstücker, Jak je to s Franzem Kafkou?, p. 5.

48 See also Klaus Wagenbach, Franz Kafka. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt [1964] 1991, p. 17, as well as Max Brod, Franz Kafka. Eine Biographie (Franz Kafka: A Biography). Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1963, p. 7. According to Gustav Janouch, Franz Kafka himself also interpreted his name along these lines. See Gustav Janouch, Gespräche mit Kafka. Aufzeichnungen und Erinnerungen (Conversations with Kafka. Notes and Memoirs). Extended edition. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer [1968] 1981, p. 30.

49 Goldstücker, Na téma Franz Kafka, p. 7.

50 Wagenbach, Franz Kafka, p. 17, and Klaus Wagenbach, Franz Kafka. Prague: Mladá fronta [1965] 1993. Czech aspects in the family history are already a feature of his 1958 biography of Kafka. Klaus Wagenbach, Franz Kafka: Eine Biographie seiner Jugend 1883–1912 (Franz Kafka: A Biography of his Youth 1883–1912). Bern: Francke 1958.

51 See Wagenbach, Franz Kafka, 1991, p. 16. I interpret them as specific local variants typical for Hermann Kafka’s time. See Marek Nekula, Deutsch und Tschechisch in der Familie Kafka (German and Czech in the family Kafka). In: Dieter Cherubim – Karlheinz Jakob – Angelika Linke (eds), Neue deutsche Sprachgeschichte. Mentalitäts-, kultur- und sozialgeschichtliche Zusammenhänge (New German History of Language: Mentality, Culture and Social History). Berlin, New York: W. de Gruyter 2002, pp. 379–415.

52 Wagenbach, Franz Kafka, p. 16.

53 Wagenbach, Franz Kafka, p. 16.

54 Wagenbach, Franz Kafka, 1993, p. 15.

55 Wagenbach, Franz Kafka, 1991, p. 17.

56 Goldstücker, Na téma Franz Kafka, p. 14f.

57 Reiman, ‘Proces’ Franze Kafky, p. 211.

58 Hugo Siebenschein, Prostředí a čas. Poznámky k osobnosti a dílu Franze Kafky (Milieu and time: Remarks on the personality and oeuvre of Franz Kafka). In: Franz Kafka a Praha. Vzpomínky, úvahy, dokumenty (Franz Kafka and Prague. Memories, Reflections, Papers). Prague: Žikeš 1947, pp. 7–24, p. 21.

59 For an analysis of languages in Kafka’s family see Nekula in this volume or in Marek Nekula, „. . .v jednom poschodí vnitřní babylonské věže. . .“ Jazyky Franze Kafky (‘. . . on one Floor of the Inner Tower of Babel. . .’: Franz Kafka’s Languages). Prague: Nakladatelství Franze Kafky 2003, or Marek Nekula, Franz Kafkas Sprachen und Sprachlosigkeit (Franz Kafka’s languages and the absence of language). In: brücken. Germanistisches Jahrbuch Tschechien – Slowakei. NF 15 (2007), pp. 99–130.

60 Hartmut Binder, Kafka. Ein Leben in Prag (Kafka. A Life in Prague). München: Mahnert-Lueg 1982, p. 13. My emphases.

61 Binder, Kafka. Ein Leben in Prag, p. 13.

62 Binder, Kafka. Ein Leben in Prag, p. 31. There are also Hebrew etymologies like the double use of the initial  and final letter

and final letter  (kaph, kaf, kav).

(kaph, kaf, kav).

63 With the exception of the Czech letter to the Worker’s Accident Insurance Company which Josef David wrote for his parents-in-law following Kafka’s death. This is held in the Literární archiv Památníku národního písemnictví (Literary Archive of Museum of Czech Literature). See Nekula, Deutsch und Tschechisch in der Familie Kafka, p. 379.

64 See Nekula, Deutsch und Tschechisch in der Familie Kafka, pp. 407–409.

65 Eduard Goldstücker, Dnešní potřeby, zítřejší perspektivy (Today’s needs, tomorrow’s perspectives). Literární noviny 12 (1963), No. 40, p. 9. My emphases. See also Eduard Goldstücker, Kafka, oni a my (Kafka, them and us). Literární noviny 13 (1964), No. 26, p. 1.

66 See also Roger Garaudy, Kafka a doktor Pangloss (Kafka and Dr. Pangloss). Literární noviny 12 (1963), No. 40, p. 9; Roger Garaudy, O filosofii, Picassovi a Kafkovi (On philosophy, Picasso and Kafka). Plamen 5 (1963), No. 8, pp. 1–3. For a contemporary reflection on this polemic see Jiří Hájek, Alfréd Kurella a Franz Kafka, aneb o podmínkách principiální polemiky (Alfred Kurella and Franz Kafka, or on the conditions for a controversy over principles). Plamen 5 (1963), No. 10, 131.

67 Vítězslav Rzounek, Poznámka o pojetí stranickosti v epice (Remarks on the concept of party-mindedness in epic literature). Česká literatura 11 (1963), No. 3, pp. 188–192.

68 On the stance of German Studies on Kafka in East Germany and the interweaving of literature and politics in relation to 1968 see the article by Steffen Höhne, 1968, Prag und die DDR-Germanistik. Zur Verflechtung von Ideologie und Politik in der Kafka-Rezeption (1968, Prague and GDR German Studies: Ideology and politics in Kafka’s reception). In: Wolfgang Adam – Holger Dainat – Günter Schandera (eds), Wissenschaft und Systemveränderung: Rezeptionsforschung in Ost und West – eine konvergente Entwicklung? (Scholarship and System Change? Reception Research in East and West: A Convergent Development?) Heidelberg: Winter 2003, pp. 225–244.

69 Goldstücker, Jak je to s Franzem Kafkou?, p. 4.

70 See Benno Wagner, Fürsprache – Widerstreit – Dialog: Karl Kraus, Franz Kafka und das Schreiben gegen den Krieg (Recommendation – conflict – dialogue: Karl Kraus, Franz Kafka and the writing against the war). In: Manfred Engel – Ritchie Robertson (eds), Kafka, Prag und der Erste Weltkrieg. Kafka, Prague, and the First World War. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann 2012, 257–278, and Benno Wagner, „Sprechen kann man mit den Nomaden nicht“. Sprache, Gesetz und Verwaltung bei Otto Bauer und Franz Kafka (‘It is impossible to speak with nomads’. Language, law and administration in Otto Bauer and Franz Kafka). In: Marek Nekula – Ingrid Fleischmann – Albrecht Greule (eds), Franz Kafka im sprachnationalen Kontext seiner Zeit. Sprache und nationale Identität in öffentlichen Institutionen der böhmischen Länder (Franz Kafka in the National Context of His Time. Language and National Identity in the Public Institutions of the Bohemian Crown Lands). Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau 2007, pp. 109–128.

71 See Eduard Goldstücker, O přístupu ke Kafkovi (On the approach to Kafka). Literární noviny 12 (1963), No. 11, pp. 4–5, as well as Ivo Fleischmann, O čem psal Franz Kafka? (What did Franz Kafka write about?). Literární noviny 12 (1963), No. 13, pp. 4–5.

72 Eduard Goldstücker, O přístupu ke Kafkovi, p. 4 f.

73 Marie Majerová, Zahajovací projev (Opening speech). In: Eduard Goldstücker – František Kautman – Pavel Reiman (eds), Franz Kafka: liblická konference 1963 (Franz Kafka: Liblice Conference 1963). Prague: ČSAV 1963, p. 9.

74 Pavel Reiman, Kafka a dnešek (Kafka today). In: Eduard Goldstücker – František Kautman – Pavel Reiman (eds), Franz Kafka: liblická konference 1963 (Franz Kafka: Liblice Conference 1963). Prague: ČSAV 1963, pp. 13–20. Reiman also had a presentation and closing words to the conference. See Pavel Reiman, O fragmentárnosti Kafkova díla (On the fragmentarity of Kafka’s oeuvre). In: Eduard Goldstücker – František Kautman – Pavel Reiman (eds), Franz Kafka: liblická konference 1963. Prague: ČSAV 1963, pp. 213–218; Pavel Reiman, Závěrečné slovo (Closing words). In: Eduard Goldstücker – František Kautman – Pavel Reiman (eds), Franz Kafka: liblická konferen“ce 1963. Prague: ČSAV 1963, pp. 275–277.

75 Goldstücker, O přístupu ke Kafkovi, p. 5; Goldstücker, Na téma Franz Kafka, 64; Eduard Goldstücker, Über Franz Kafka aus der Prager Sicht, p. 26.

76 Goldstücker, Na téma Franz Kafka, p. 73.

77 František Kautman, Franz Kafka a česká literatura (Franz Kafka and Czech literature). In: Eduard Goldstücker – František Kautman – Pavel Reiman (eds), Franz Kafka: liblická konference 1963 (Franz Kafka: Liblice Conference 1963). Prague: ČSAV 1963, pp. 39–75. For further early publications on this topic see František Kautman, Ještě jednou Franz Kafka z pražské perspektivy (Franz Kafka, once again from the Prague perspective). Plamen 6 (1964), No. 8, pp. 165–166, as well as František Kautman, Franz Kafka a Čechy (Franz Kafka and Bohemia). Literární archiv 1 (1966), pp. 179–197.

78 The conference was also commented upon in Věra Macháčková, Konference o díle Franze Kafky (Conference on the work of Franz Kafka). Rudé právo, 31.5.1963, p. 3.

79 See Václav Černý, První sešit o existencialismu (The First Book on Existentialism). Prague: Václav Petr 1948, p. 24 f., or Čermák, Die Kafka-Rezeption in Böhmen, p. 232.

80 Černý published the same on Kafka in a Slovak journal. Václav Černý, Hrsť poznámok o kafkovskom románe a o kafkovskom svete (Some comments on Kafka’s novel and on Kafka’s world). Slovenské pohľady 79 (1963), No. 10, pp. 80–95.

81 Václav Černý, Paměti 1945–1972 (Memoires 1945–1972). Brno: Atlantis 1992, p. 475.

82 See Kafka, Neznámé dopisy Franze Kafky, and Loužil, Dopisy Franze Kafky.

83 See Franz Kafka, Briefe an Ottla und die Familie (Letters to Ottla and Family). Edited by Hartmut Binder and Klaus Wagenbach. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer [1974] 1975; Kafka, Letters to Friends. . .; Franz Kafka, Amtliche Schriften (Office Writings). Edited by Klaus Hermsdorf. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag 1984.

84 Siebenschein, Prostředí a čas, p. 21f.

85 In the next edition of 1968 Janouch put further coals on the fire of the Czech bias by adding further details. See Gustav Janouch, Gespräche mit Kafka (Conversations with Kafka). Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1951. For more details on this see Marek Nekula, Poznámky (Comments). In: Gustav Janouch, Hovory s Kafkou (Conversations with Kafka). Translation by Eva Kolářová, ed. by Marek Nekula, afterword by Veronika Tuckerová. Prague: Torst 2009, pp. 223–252.

86 See Klaus Wagenbach, Franz Kafka. Eine Biographie seiner Jugend 1883–1912 (Franz Kafka: A Biography of his Youth 1883–1912). Berlin: Wagenbach 2006, p. 19, 23.

87 Franz Kafka, Kafka inconnu. Translation by O. Beneš and Paul Lecler. La vie tchécoslovaque 11 (1963), No. 10, pp. 26–27.

88 Josef Čermák, Zpráva o neznámých kafkovských dokumentech (Report on unknown Kafka documents). In: Eduard Goldstücker – František Kautman – Pavel Reiman (eds), Franz Kafka: liblická konference 1963 (Franz Kafka: Liblice Conference 1963). Prague: ČSAV 1963, pp. 249–252.

89 The edition in Franz Kafka, Dopisy Ottle a rodině (Letters to Ottla and Family). Translation, annotation and afterword by Vojtěch Saudek. Prague: Aurora 1996, is however not without errors and was only corrected in Franz Kafka, Dopisy rodině (Letters to Family). Translation by Vojtěch Saudek. Edited and commentary by Václav Maidl and Marek Nekula. Prague: Nakladatelství Franze Kafky 2005, and Franz Kafka, Briefe 1914–1917 (Letters 1914–1917). Edited by Hans-Gerd Koch. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 2005; Franz Kafka, Briefe 1918–1920 (Letters 1918–1920). Edited by Hans-Gerd Koch. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 2013.

90 For further on this see, facsimiles of the texts in Nekula, Jazyky Franze Kafky, and ib. pp. 84–94. My emphases.

91 Kafka, Neznámé dopisy Franze Kafky, p. 93.

92 A similar approach can be found in Zdeněk Nejedlý’s corrective interventions in the edition of letters written by Friedrich/Bedřich Smetana and member of his family; it was on the basis of this edition that he underpinned his assumption of the nationalist and purely Czech orientation of the Smetana family. See Marek Nekula – Lucie Rychnovská, Smetanova čeština v dobovém kontextu (Smetana’s Czech in historical context). Hudební věda 47 (2010), No. 1, pp. 43–76.

93 Loužil, Dopisy Franze Kafky, p. 59.

94 Verified individually in Nekula, Jazyky Franze Kafky. Friedrich/Bedřich Smetana also proceeded in a similar fashion. He is another example of a figure co-opted for Czech culture, who, unlike Kafka however, became involved after 1861 in the national culture and its network of organisations. See Marek Nekula – Lucie Rychnovská, Bedřich Smetana’s use of the Czech language. In: Musicalia. Journal of the Czech Museum of Music 1 (2012), No. 1–2, pp. 6–38.

95 Anna Pouzarová, Ze vzpomínek vychovatelky v rodině Franze Kafky (From the memoirs of the governess in Franz Kafka’s family). Recorded by Hanuš Frank and Karel Šmejkal. Plamen 6 (1964), pp. 104–107; Frank Hanuš – Karel Šmejkal, Po stopách Franze Kafky do jižních Čech (On the trail of Franz Kafka in South Bohemia). A. Pouzarová’s memoirs recorded by Hanuš Frank and Karel Šmejkal. Práce, 16.2.1964, p. 5.

96 Pavel Eisner is convinced that the idea of the erotic appropriation of another culture can even serve as a general model for German literature in Prague and Bohemia. See Pavel Eisner, Milenky. Německý básník a česká žena (Lovers. The German Writer and the Czech Woman). Prague: Dolínek 1930.

97 Franz Kafka, Briefe an Milena (The Letters to Milena). Edited and with an afterword by Willy Haas. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1966.

98 See Reiman, ‘Proces’ Franze Kafky, p. 225.

99 Kautman, Franz Kafka a česká literatura; František Kautman, Franz Kafka und die tschechische Literatur (Franz Kafka and Czech literature). In: Eduard Goldstücker – František Kautman – Paul Reimann (eds), Franz Kafka aus Prager Sicht 1963 (Franz Kafka from the Prague Perspective 1963). Prague: ČSAV 1965, pp. 44–77.

100 See, for example, Ivo Fleischmann (ed.), Franz Kafka a náš svět (Kafka and our world). Articles by Eduard Goldstücker, Ernst Fischer, Roger Garaudy, Ivan Sviták. Literární noviny 12 (1963), No. 23, p. 3; Karel Kosík, Hašek a Kafka neboli groteskní svět (Hašek and Kafka, or the grotesque world). Plamen 5 (1963), No. 6, pp. 95–102; Hanuš – Šmejkal, Z vzpomínek vychovatelky v rodině Franze Kafky; František Kautman, Boje o Kafku včera a dnes (Disputes over Kafka then and now). Literární noviny 14 (1964), No. 27, p. 5; František Kautman, Pražská německá literatura (German literature in Prague). Literární noviny 14 (1964), No. 48, p. 4.

101 Goldstücker, Dnešní potřeby, zítřejší perspektivy, p. 9. My emphases.