THE ‘BEING’ OF ODRADEK:

FRANZ KAFKA IN HIS JEWISH CONTEXT

Some say the word Odradek is of Slavonic origin and seek to trace its derivation on that basis. Others believe it was originally German and was merely influenced by the Slavonic. The uncertainty surrounding both interpretations, however, suggests that perhaps neither is correct, particularly since neither of them furnishes a meaning for the word.1

This passage concerning the uncertain origin of the word Odradek is from Kafka’s story ‘The householder’s concern’, written in 1916–17 and included in the collection A Country Doctor: Short Stories, published by Kurt Wolff in Munich and Leipzig on 12 May 1920. Not only is the origin of the word (and, incidentally, of the ‘householder’s concerns’) unclear: there is no telling who or what Odradek actually is. Pavel Trost attempted to answer the second question by considering the first. Taking up the etymological challenge posed at the start of the story itself, Trost decided on the Czech option and, removing the apparently diminutive suffix -ek from the Czech neologism Odradek, interpreted the remaining ODRAD as a coded form of the name KAFKA.2 In this way he connected the story about the ‘concerns of the householder’ with Kafka’s own family life. It also makes sense if we read the fragment ODRAD in the Hebrew manner, from right to left; even more so if we see in Gregor SAMSA in ‘The metamorphosis’, as well as in K. in Josef K. in The Trial and in The Castle, an allusion to Kafka’s name, which means ‘jackdaw’ and also plays a role in other stories, notably in ‘A page from an old manuscript’ and ‘The hunter Gracchus’.

However, Trost’s answer to the first question is imprecise, while any answer to the second, as to who Odradek actually is, is problematic. As the story itself indicates, the word odradek does not exist in any Slavonic language (and thus not in Czech), just as the being named Odradek has no real existence. But in principle it could very easily be a Czech word – and one with a fairly clear meaning. The root odrad- immediately suggests the verb odradit, which has the following approximate meanings: 1) to deter, discourage or spoil the pleasure or interest of someone in something, to take away someone’s joy or resolve, to intimidate, to estrange someone from something; 2) to put someone off another person, to spoil someone’s relationship with or liking for another person.3 In this case, unlike in Trost’s interpretation, the -ek is not a diminutive suffix but a suffix denoting the result of an action, analogous to words like výrob-ek (=product, from vyrob-it, to produce).4 This would give the word odradek the meaning ‘something created through discouragement or intimidation’. It is a peculiar feature of such formations that they denote only concrete or abstract objects, but not persons – that is, not sentient, thinking beings with the capacity to be discouraged or intimidated. Odradek, however, is an oddity. For the father (i.e. the ‘householder’) it is only a Wesen (‘being’) or Gebilde (‘entity’), a mere es (‘it’) which therefore cannot die; yet at the same time it is clearly more than a mere ‘it’, since er (‘he’) can move around, laugh, talk and be silent. If we accept Trost’s interpretation that there is a link between Odradek and Kafka, and the assumption that Kafka’s story obliquely refers to his own relationship with his father, then the writer who created this word and mentions its ‘derivation’ must have had a very good knowledge of Czech.

While Czech etymology can make sense of the word,5 any attempt at a German derivation is doomed to fail, notwithstanding the observation in the story that ‘andere meinen, es stamme aus dem Deutschen, vom Slawischen sei es nur beeinflußt’ (‘others believe it was originally German and was merely influenced by the Slavonic’). This is a paradox that points either to another language or beyond language altogether. But both ‘some’ and ‘others’ address the question of Odradek’s existence only from an external point of view and in relation to language: Odradek is reduced to ‘das Wort Odradek’ (‘the word Odradek’) and his/its existence to a matter of linguistic appurtenance. Here, too, it is not hard to read biographical allusions into the text: the ‘word’ as a cipher for Kafka’s writing; the external assigning of linguistic identity as a metaphor for linguistic polarization in a land peopled by both Czechs and Germans. The Kafka family had to deal with this polarization at every school admission, at every census time, and in everyday reality, where the question of their linguistic identity ignored another reality, another identity. In contrast to all other members of the Kafka family, who declared Czech as their common language, German was entered as the common language next to Franz Kafka’s name in the 1910 census.6 It is inconceivable that this disparity would not have led to a ‘clash with the father’;7 Franz Kafka lived with his family in a single household and the declared language his father provided for the rest of the family was called into question by Franz Kafka’s entry. This was one of the conflicts that came to a head in Kafka’s family in and after 1910, besides his perceived lack of commitment to the factory and his Jewish ‘rebirth’.

Not long after Kafka wrote ‘The householder’s concern’, Max Brod addressed similar issues in his essay ‘Jews, German, Czechs’. Writing in July 1918, he said:

I do not feel myself to be a member of the German people, but am a friend of Germanness and also, by language and education [. . .], culturally related to Germanness. I am a friend of Czechness, yet am in essential ways [. . .] culturally detached from Czechness. I cannot find a simpler formulation for an existence in the Jewish diaspora of a nationally divided city.8

If ‘the uncertainty surrounding both interpretations [. . .] suggests perhaps neither is correct, particularly since neither of them furnishes a meaning for the word’, it might be better to move away from the linguistic derivation of Odradek and the external perspective of ‘some’ and ‘others’, and focus instead on the ‘being’ of Odradek, as Kafka did in his story.

In the second paragraph of the story, which considers Odradek’s Wesen (being), he/it is described as a ‘eine flache sternartige Zwirnspule’ (‘a flat, star-shaped spool’).9 Under ‘Spule’, Grimm’s dictionary gives the Austrian dialect usage of the word (meaning No. 8) as ‘Quirl’ (‘a whisk’), a utensil which in its traditional Central European form has a star-shaped wooden head.10 Grimm also lists the expression ‘Zwirnstern’ (‘a star-shaped spool’).11 The phrase ‘eine flache sternartige Zwirnspule’ (‘a flat, star-shaped spool’) can thus be seen as referring to the Star of David, and hence to Jewishness in general. But this is no proud ‘being’, no unequivocal identity. The Star of David-shaped ‘Odradek’ is described in terms of ‘rupture’, ‘fissure’ and ‘senselessness’ – undermining any belief in a fixed, authentic, ‘organic’ and hence meaningful Jewish identity:

At first it looks like a flat, star-shaped spool for thread, and in fact, it does seem to be wound with thread, although these appear to be only old, torn-off pieces of thread of the most varied sorts and colours [. . .] / It is tempting to think that this figure once had some sort of functional shape and is now merely broken. But this does not seem to be the case; at least there is no evidence for such a speculation; nowhere can you see any other beginnings or fractures that would point to anything of the kind; true, the whole thing seems meaningless yet in its own way complete.12

This interpretation is supported by others traits of Odradek – ‘beweglich’ (nimble), ‘nicht zu fangen’ (cannot be caught) and ‘unbestimmter Wohnsitz’ (‘of no fixed abode’) recalling the rootlessness of the Jews as a result of repeated expulsions. This sort of ‘being’, which used to be called Jewish, is more than simply ‘the householder’s concern’ in Kafka’s story. The battle over Jewish identity was a problem in Kafka’s relationship with his father as well as with respect to his civil identity. Thus ‘beings’ like Odradek were defined not only ‘from within’, but also ‘from outside’, as the allusion to the antisemitic figures, like ‘of no fixed abode’, in this story shows.

There are also other specific allusions in this story, such as the reference to Odradek’s laugh, which sounded ‘wie man es ohne Lungen hervorbringen kann’ (‘[like the kind of laugh] that can be produced without lungs’ and ‘wie das Rascheln in gefallenen Blättern’ (‘like the rustle of fallen leaves.’). This can be understood autobiographically as a recollection of the first symptoms of Kafka’s pulmonary illness, which appeared in August 1917 and were diagnosed in early September. That is why in this chapter I shall, exceptionally, follow the biographical path taken by Trost and others and go back to the origins of Franz Kafka and his family, linking their story to that of the Jews’ emergence from the ghetto and the struggle for Jewish identity.

OUT OF THE GHETTO

In Austria and Bohemia, it is customary to date the first crumbling of the ghetto walls to 1781, when Joseph II made life easier for non-Catholics in the Habsburg Empire. But the emancipation of the Jews did not proceed smoothly – neither at the political level nor in public life. The decree of 1781 relaxed legal restrictions on the Jewish population initially only in commerce. The regulations and directives that followed in the 1780s and 1790s were eventually codified in a systematic review of Jewish legislation (the Judensystemalpatent) in 1797.13 Jewish inclusion in the community also entailed obligations, among them limitations on the role of religion. The abolition of rabbinical courts and use of German in 1784 was the first step in that direction. Jews in the Bohemian lands had to take non-composed non-Jewish (German) surnames (1787),14 attend German-language schools,15 use German in dealings with the authorities (e.g. in public registers and accounts books) and so on. The fears of some rabbis of a decline in the use of Hebrew and Yiddish (which Kafka’s south Bohemian grandparents had still spoken) were already being realized in the first half of the 19th century.

Discrimination in its various forms – from the law limiting the number of Jews entitled to an official wedding ceremony (which included Kafka’s grandparents) to restrictions on freedom of movement, continuing isolation in the ghettoes, low levels of tolerance, and stigmatization by the use of ‘particular’ surnames – disappeared only gradually. Thus the name Kafka (from kavka [kafka] = jackdaw) could be classed as one of those names that could stigmatize their bearers by referring to some supposedly typical characteristic such as hair colour or texture (Kafka, Schwarz (Black), Roth (Red); Kraus (Curly) etc.), nose shape (Nossig or Nosek) or pronunciation (Khon, Khol rather than Kohn, Kohl). When in 1836 Jews were given the option of dropping their hitherto prescribed, mainly Hebrew first names like Moses and Sarah and adopting neutral German names, many took it up. Kafka’s forbears born before that year all had names like Josef, Jakob, Isaak, Adam, Samuel, Sara, Salamon, and Jonas, while members of Kafka’s parents’ generation tended to have ‘German’ names such as Heinrich, Hermann, Ludwig, Alfred, Richard, or Philip.16 The right to use Czech first names, introduced as part of the repeal of discriminatory legislation after 1848, had little effect on established practice, at least not for a while. Thus in the Kafka family, apart from Franz himself, there were his siblings Georg (1885–86), Heinrich (1887–88), Gabriela (1889–1941), Valerie (1890–1942) and Ottilie (1892–1943). An exception in that generation was Franz’s cousin Zdeněk, son of his uncle Philip (or Philipp – both forms can be found in Hermann Kafka’s letter of 25 July 1882) and his wife Klára Kafka, née Poláček.

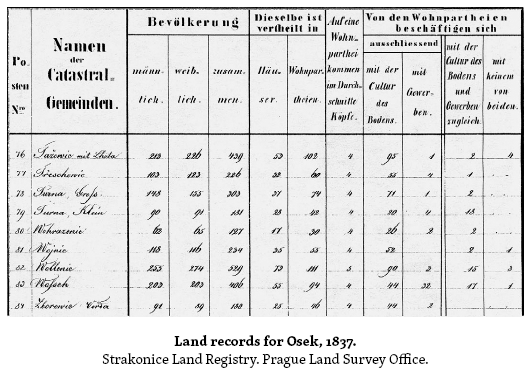

The Kafkas’ road out of the ghetto can be mapped not only through their names but in the ghetto itself and its dissolution. Johann Gottfried Sommer records that in the 1830s there were 50 houses and 382 inhabitants in the south Bohemian village of Osek near Strakonice, where Kafka’s paternal grandfather and his family lived.17 In regions of mixed nationality such as this, the majority of the population in rural communities was Czech while the elites and holders of administrative authority tended to be German. Sommer tells us there were twenty Jewish families in Osek in the late 1830s18 – though that figure only included families approved under a law regulating the number of Jewish families. That means that in Osek – or rather Little Osek, in Jewish Street and around the Synagogue – there was a community of around a hundred. Die Notablenversammlung der Israeliten Böhmens in Prag (The Prague Compendium of Notable Jews in Bohemia) records 20 families and 95 community members.19 An 1837 map shows nineteen houses in Jewish Street alone, with another sixteen beyond the synagogue on the road to Radomyšl; in the ‘Christian’ part of the village there were seventeen houses.20 The land register for the year 1837 lists a total of 55 houses (including the castle), 94 ‘residential units’ and 406 inhabitants – making an average of four people per household. That would mean 32.3 residential units in Jewish Street, a figure corresponding to that in the register (32) for households occupied by those engaged in the trades Jews were allowed to pursue before 1848. On this basis we can assume that 130–140 people lived in Jewish Street alone. Add to that the houses and dwellings on the other side of the synagogue on the Radomyšl road and we arrive at an even higher figure. Taking into account the fact that one household (such as that of Hermann Kafka’s parents) might consist of eight persons, the number of people living in Jewish Street could have been a lot higher and, combined with other Jewish families in the village, could have made up half the population of Osek. Either way, the picture we get is of a socially structured and relatively self-sufficient Jewish community.

At its centre was the synagogue, where the roads from Malá Turná (1 km) and Radomyšl (3 km) met, next to the village inn. The village butcher – Jakob Kafka (1814–1889), Franz’s grandfather – lived in Jewish Street. In the ‘next street’, at right angles to Jewish Street, were a general store and a tailor’s. Besides merchants and peddlers Little Osek also had its cobbler and its glazier.21 Data from 1837 show that 44 households (‘Wohnpartheien’) in Osek were engaged in agriculture (‘mit der Cultur des Bodens’), 32 in trades (‘mit Gewerben’), 17 in both agriculture and trades (‘mit der Cultur des Bodens und Gewerben zugleich’), and one in neither (‘mit keiner von beiden’). The 32 households engaged in trades were presumably the non-privileged Jews in Jewish Street, for whom owning land and working it was hardly an option.

Alena Wagnerová believes there was also a privileged Jewish ‘upper class’ in Osek – leaseholders of the brewery, distillery, etc.22 – an assumption supported by an 1837 record of a Jewish hospital near the synagogue.23 This ‘upper class’, however, would probably have thought of itself as German, as the Czech-Jewish movement did not emerge with any force until the 1870s.24 It can thus be assumed that German was spoken both in the synagogue and in religious instruction lessons. Hebrew was only used during the liturgy itself, while Yiddish in the culturally mixed community gradually diminished in importance – although Hermann Kafka, according to his son, continued to pepper his speech with Yiddish expressions even in old age.25 We know that Osek had its own rabbi between 1823 and 1827;26 otherwise it shared one with the similarly-sized Jewish communities of Písek and Strakonice. The district rabbi lived in Strakonice (about 10 km south of Osek), and the local rabbi in Horažďovice.27 The community also had a shamas or warden to look after the synagogue, who doubled as a German teacher.28 Merchants would seek trade not only in the immediate locality, but as far afield as Písek fifteen kilometres to the east, so it must be assumed that owing to the predominance of Czechs in the region the merchants, at least, must have spoken Czech. This was also true of Hermann Kafka and his relatives. Franz Kafka, writing of his sister Valli’s wedding in a letter to Felice dated 13 or 14 January 1913, quotes his father’s use of the Czech word ‘kněžna’ (princess) to describe the bride.29

The revolution and reforms of 1848, and in particular the March Constitution of 1849, brought an end to the visible ghetto. The administrative inclusion of Jews in rural communities was certainly a step forward in terms of emancipation, but it did not lead to full social acceptance or integration. Franz Kafka’s father Hermann (1852–1931), who was born in Jewish Street in Osek, still knew what it was like to live in the confines of a ghetto. Little Osek, as the Jewish quarter was known, was separated from the rest of the village by the castle, open land, ponds and marshland. From the synagogue, known locally as ‘the church’, it was a walk of eight or nine hundred metres to the little chapel outside the castle in the Christian part of the village. The fact that one had to walk around the castle and its grounds to get there only added to the isolation of the Jewish part of the village. From the castle there was a direct and shorter path to Little Osek, which went on to Turná, Radomyšl a Strakonice; but it was not a public road.

In many ways the Catholics of Osek led a quite separate life. They had their own inn and smithy, their own merchant, and so on. But there was no Czech school in the village, which meant that children requiring a Czech education had go to Jemnice, a walk of about two kilometres. The road there was on the other side of the village from the Jewish quarter, so that in the 1850s when Hermann Kafka was a boy neither the children nor the adults of Osek had much everyday contact with each other and people tended to look for partners within their own communities, be they Catholic or Jewish. Before his marriage Jakob Kafka lived in house No. 30, his bride Franziska Platowski in No. 35.30

From the present perspective it is hard to say to what extent anti-Jewish sentiment impinged on daily life in Osek. We do know, however, that in 1861 in Strakonice, only ten kilometres away, there were anti-Jewish pogroms and that the army was called in to restore order.31 We know equally, however, that besides their economic interaction the Jews kept themselves apart, within their own rhythms and routines and cultural confines. Kafka’s mention of the ghetto in his Letter to Father is therefore very pertinent:

You really had brought some traces of Judaism with you from the ghetto-like village community; it was not much and it dwindled a little more in the city and during your military service; but still, the impressions and memories of your youth did just about suffice for some sort of Jewish life [. . .]32

The language laws proved particularly enduring. Although the March Constitution of 1849 and subsequent amendments gave Jews a free choice in declaring their children’s first language when enrolling them for school, German remained the most common preference. There were various reasons for this: identification with German as the language of emancipation; German as a precondition for a good education, social advancement and better career opportunities; but also the lack of Czech schools, or their limited capacity. Under the Bach system in the 1850s ‘teaching in the Czech language was restricted’33 and it was not until the 1860s and 1870s that a proper network of both Czech and German schools began to emerge in linguistically mixed areas. One such area was Little Osek, where Hermann Kafka almost certainly attended a German school.34

German (Jewish) schools were usual at the time, even in areas with a predominantly Czech population.35 One such school in nearby Strakonice survived until 1898.36 A fairly sure indication that Hermann Kafka did indeed have a German education is the ‘German’ Kurrent script taught in the German schools of the time which he uses in his letters to his future wife Julie Löwy (1854–1934) in 1882.37 Czech schools, on the other hand, were already teaching a modified form of Latin script introduced in 1849.38

It is therefore quite likely that Hermann Kafka could not write Czech. A number of ‘Czechisms’ that appear in his German letters to Julie Löwy in German show that Hermann Kafka had – like his wife – considerable difficulty with Czech spelling:

Přibik for ‘Přibík’, Tabor for ‘Tábor’, Pisek for ‘Písek’, Budín for ‘Budyň’, Götzova for ‘Götzová’, Daňek for ‘Daněk’, Kc for ‘Kč’ (Czech crowns), Mseno for ‘Mšeno’.39

In the case of the word Daňek (instead of the correct Daněk) he fails to apply the spelling rule taught in the first class of elementary school that a palatalized /ň/ before /e/ is spelt -ně- not -ňe-. With the word Budín (instead of the correct ‘Budyň’ or ‘Budyně’) he fails to distinguish between the palatal /ď/ and the alveolar /d/, which requires the spelling -dy- rather than -di-. He also omits diacritics, or puts them in the wrong place.

It must be said that Hermann Kafka also had difficulty with German orthography, as a result of his inadequate schooling. For he had ‘already at the age of ten to push a handcart round the villages even in winter and very early in the morning’;40 and ‘aged seven I already had to take the handcart round the villages’.41 In his dealings with customers in the villages he would have needed both languages.

But it was German that enjoyed the higher status in the Kafka family and generally in this time. German was essential for communicating with many of Hermann Kafka’s clients and business partners in Prague and Vienna.42 It was also of central importance in his personal life, being the language of his correspondence with Julie Löwy before they were married. After his marriage and the birth of their children, who had German names and went to German schools, this tendency became even more marked. Hermann Kafka almost certainly spoke German with his wife and children; he and his family went to the German synagogue; he enrolled his children in German schools, read the newspapers Bohemia and Prager Tagblatt43 and had various announcements published in the German press.44 Letters to the children were also in German, though these were mostly written by their mother, who used Czech vocative and diminutive forms of their names such as Liebste Ottilko!, Liebste Otilko! and Liebe Ottilko!, or Liebste Ellynko!, Liebe Ellynko, etc.45 – the same forms her husband had once used in his letters to her: Vielgeliebte Julinko, Liebe Julinko or simply Julinko.46 For Julie Czech was not only a language of affection; she had a very thorough knowledge of spoken Czech.47

The privileged status of German in Kafka’s parents’ family can also be seen in the inscription on the gravestone of Hermann Kafka’s father and Franz Kafka’s grandfather Jakob – clearly a context of special emotional significance. On the upper part the gravestone there is a Hebrew inscription, and below it in German ‘Friede seiner Asche’ (Peace to his ashes). All but two of the other gravestones in the forest cemetery at Osek (there are 39 in total) have only Hebrew inscriptions. David Hollub has both Hebrew and German, while Julie Auler has only German. A similar, though more striking illustration of the growing importance of German rather than Hebrew in such symbolic contexts, can also be found in other Jewish cemeteries, such as the one in Trebitsch/Třebíč. In practical daily life this trend was even more obvious. By 1900, 91% of the Jewish children registered at German schools in Prague,48 even though many came from predominantly Czech areas. Migration from rural areas to the cities and industrial and commercial centres,49 which in the case of the Jews was connected with the disappearance of the vestiges of the old ‘visible’ ghetto, is reflected in the declining population of Osek detailed in the local land register. In fact Franz Kafka’s grandfather was the last Jewish inhabitant of Osek to be buried in the Jewish forest cemetery, in 1889.50 Čapková points out that ‘whereas in 1872 there were 327 Jewish religious communities in Bohemia, in 1890 there were only 247’ and that by 1921 69% of the Jewish population lived in towns of over 10,000 inhabitants.51

CZECHS? GERMANS? ‘THE UNCERTAINTY SURROUNDING BOTH INTERPRETATIONS. . .’

The process of emancipation took place in a time of optimistic liberalism and growing indifference to religion,52 the latter – more pronounced in Bohemia than elsewhere53 – becoming particularly apparent towards the end of the century. Hermann Kafka, on an invitation dated 1896, paraphrases bar– mizwe of his son as Confirmation.54 Julie Kafka, in a private family letter of 14 December 1917, writes of the Weihnachts Feiertage, and for Franz Kafka the word Weihnachten (Christmas) also has a personal resonance,55 whereas Max Brod preferred the term Chanuka.56 These are two different linguistic and cultural regimes coming together. Significantly, this acculturation was also reflected in language use. In the first phase of emancipation, acculturation to German language and culture came quite naturally to the Bohemian and Moravian Jews. German was not only the language of their emancipation and an expression of their social aspirations; for seventy years – from the 1780s till the mid-19th century – they were required by law to use German in all stipulated spheres of public life. Both in Bohemia, where before 1848 Jews were also allowed to live in rural communities, and in Moravia, where they tended to settle in small towns, living side-by-side with the Czech-speaking population provided ideal conditions for acquiring Czech culture and language, though this did not happen as a matter of course. Acculturation to Czech culture became easier following new legislation after 1848 and in the 1860s57 that granted Jews equal rights, including the right of choice of language in the school system. In Prague this trend became apparent in the mid-1870s, intensifying in the 80s and 90s when a new generation made its presence felt in cultural and public life – young Jews born after 1848 or those who had come to the capital to study or in search of work.

A milestone in the self-organization of the Jewish community in the secular sphere was the founding of the Spolek českých akademiků židů (Society of Czech Academic Jews) in 1876. The following years were characterized by the dynamic growth of the Czech-Jewish movement that continued until the mid-90s. Even in the First Czechoslovak Republic, this movement remained an important intellectual trend in the Jewish community.58 1881 saw the first publication of the Kalendář česko-židovský (Czech-Jewish Calendar), which from 1918 to 1920 was edited by Alfred Fuchs, whom Kafka knew personally. In 1883 a group was set up called Or-tomid (Eternal Light), which in 1886–87 successfully campaigned for the liturgical use of Czech. In the same period, Hebrew prayer books were published with Czech interlinear translations.59 Sedláček’s Základové hebrejského jazyka biblického (Biblical Hebrew Primer) came out in 1892. It was the first textbook of Hebrew language written in Czech for academic purposes, and Kafka owned a copy.60 Shortly afterwards, another modern Czech textbook of Hebrew appeared, written by Richard Feder, a rabbi from Kolín, whose Židovské besídky (A Jewish Miscellany) also attracted attention. That too was a book Kafka possessed, as we shall see in the chapter on his reading. In 1893 the various Jewish organizations finally came together under the umbrella Národní jednota českožidovská (Czech-Jewish National Unity), while in 1894 the Českožidovské listy (Czech-Jewish Newspaper), printed in Czech, appeared, first as a fortnightly then (from 1897) as a weekly. As the names of these societies and publications indicate, Czech-oriented Jews saw themselves as an integral part of Czech society, whereas those aligned with the German community were firmly integrated into German institutions of every kind such as the Verein Deutsches Casino (German Club), founded in 1862 and renamed as the Verein Deutsches Haus in 1916, or the Lesehalle der deutschen Studenten in Prag (Reading Hall of German Students in Prague), founded in 1848 and later renamed the Rede- und Lesehalle der deutschen Studenten in Prag, where they played an important if not a leading role.

Wagenbach, who claims that Hermann Kafka ‘in his first years in Prague felt like a Czech and was regarded as a Czech’,61 locates him in the Czech-Jewish movement:

Thus in this period he was a board member of the synagogue in Heinrichgasse (Jindřišská), founded in around 1890, the first Prague synagogue where services were conducted in Czech.62

The assertion proves problematic, however, when we realise that even in 1897 Or-tomid was still unable to fund a permanent synagogue.63 True, the group did try in the late 1890s to raise money for a Jewish house of worship in Heinrichsgasse,64 but it was not until 1905–06, following a decision made in 1898, that the first synagogue in this part of Prague was built, in nearby Jerusalem Street. Wagenbach’s claim that Hermann Kafka was on the board of a ‘synagogue’ in Heinrichsgasse remains without support, either from contemporary testimony65 or from written sources, and I have been unable to find the name Hermann Kafka in the Czech-Jewish Calendar for the period in question. Considering that the Calendar regularly printed lists of the members of the Society of Czech Academic Jews, the Or-tomid association, reading clubs, ball committees, etc., the ‘omission’ of a board member of a ‘Czech synagogue’ would have been almost unthinkable. But this is not the only evidence against Wagenbach’s hypothesis.

On 25 December 1893 a general meeting was held in the ‘Gypsy’ Synagogue (at the time the Kafkas’ local synagogue) at which the building of a new house of worship was discussed.66 The invitation was acknowledged by 123 members of the Community, as their signatures testify (the names of three members are missing). Against the name ‘Kafka H.’ on page five of the invitation and page three of the actual list of names we find Hermann Kafka’s signature: ‘HKafka’. On the register of those present at the two-hour meeting his signature ‘Herman Kafka’ again appears, as number thirty-six out of only forty-nine Community members who attended.

The protocol of the meeting gives us a good idea of the content and character of the debate, which focussed on the ‘asanation’ (asanace), i.e. clearance and redevelopment of the inner city proposed by a law passed earlier that year, including the building of a new temple to replace the condemned ‘Gypsy’ Synagogue:

Chairman Mr Jos. Inwald opened the meeting and gave the floor to Mr Gottfr. Weltsch, who read out the following resolution, unanimously passed by the whole committee on 23 December 1893:

‘We the members of the Gypsy Synagogue, gathered on 25 December 1893 in an extraordinary general meeting, have conferred on our Board of Representatives Mr Josef Inwald, Mr Adolf Fischl and Mr Gottfr. Weltsch unlimited authority together to take all necessary steps and all relevant measures for the preservation of the Gypsy Synagogue, or that may be necessary for the construction of a new building in the form of a modern, large Temple sufficient to honour and grace the Jewish Community and to express, on the condition requested by Mr Jac. W. Pascheles that the divine service as practised until now will not be changed for a liturgy in any other language and that no national discord be conducted in the hitherto peaceful House of God, our fullest confidence in the Board in this matter that concerns us all.’

Mr Reach asked to speak and expressed his objections to a new building; he would be in favour of keeping the capital that the Synagogue owns and warned against taking any ill-considered steps.

Mr Pascheles opposed Mr Reach’s speech and thanked him for his concern in the good cause; he is in favour of building a Temple for today for the needs of the young generation.

Mr Weltsch also rebutted the ideas of Mr Reach and explained the Expropriation Law.

Mr Inwald entered the debate and also explained the expropriation procedure if a decision to [re]build or not to [re]build the Gypsy Synagogue is not taken within two years; he explained to the Members the various [. . .] existing reasons for building, as well as the responsibilities of the Community to their Synagogue[s]; the question arises whether the Members want to build on the present site, or whether they would prefer to undertake a new building on another suitable site and purchase the necessary plots, for which it must be said funds are not available.

Mr Weltsch then argued in favour of building outside the Josefov district, in order to make it easier for the public to visit Divine Service, and moved that the meeting be closed, which was accepted.

In an open vote of 48 in favour and one against, the Members entrusted the Board with their full confidence to proceed independently in the matter, and the foregoing resolution proposed by the Committee was accepted!

Chairman Mr Inwald thanked the Members for their unanimous trust, after which, at 12 o’clock noon, the meeting was closed.

It may be assumed that the single vote against was cast by Mr Reach. In view of the tenor of the resolution and the relatively low number of congregants present (only about a third of those invited) it is quite possible that the ‘national’ polarization between supporters of the ‘German’ and ‘Czech’ liturgy was one reason why the general meeting was convened. We can also assume that many of those who failed to attend were advocates of the ‘Czech’ liturgy, of whose existence in Prague at that time there can be no doubt (in 1892 Josef Žalud tried to found a Czech-Jewish temple),67 while among those present only one – Mr Reach – voted against the motion, albeit for different reasons. So presumably Hermann Kafka, along with the others, voted in favour of the regular liturgy and against the ‘national’ strife that was dividing not only the Jewish community – hardly the action of a committed member of Or-tormid.

Such an ideological U-turn from an alleged ‘board member’ of a Czech-Jewish synagogue ‘around 1890’ would be surprising to say the least. It might possibly have been a response to the new tough line taken by the imperial governor of Prague against Czech-Jewish associations.68 But in the light of the above it seems more likely that Hermann Kafka’s links with the Czech-Jewish movement are mere speculation. And although Čapková reminds us that it was not unusual for one individual to be involved in Jewish community activities that might seem contradictory, it would be extremely odd for Hermann Kafka to serve on the board of a ‘Czech synagogue’ so soon after he had enrolled his son in a German school in 1889. One of the Czech-Jewish movement’s primary aims, after all, was to ensure that Jewish children went to Czech schools, and successes in this endeavour were regularly reported in the Czech-Jewish Calendar.

On the other hand it is also true that in the census of 1890 the Kafkas gave their ‘common language’ as Czech, and that ‘Heřmann Kafka’ here appears in a hybrid form between German ‘Hermann’ and Czech ‘Heřman’. The surnames of Julie, Gabriela and Valerie Kafka are given as ‘Kafka’, i.e. without the Czech feminine suffix -ová,69 although Czech was declared as the Kafkas’ ‘common language’. This public inconsistency applies not only to spelling but to his attachment to national symbols. Wagenbach points out that under the name kafka – or kavka in standard orthography – on the family firm letterhead there is a sprig of oak leaves in the German version, while the Czech has a linden branch.70 For the sake of his Prague customers Hermann Kafka made a point of employing Czech staff. When one of them handed in his notice, Franz Kafka was asked to act as mediator and sort out the situation.71 Part of his negotiating strategy with the accountant was to speak to him in Czech (though not to present himself as a fellow-Czech):

[. . .] the whole afternoon in Cafe City persuading Miška to sign a declaration that he was only a commis in the firm and not required to be insured, and that Father is not obliged to pay the large supplementary payments for his insurance. He promises to, my Czech is fluent, I even apologize for my mistakes elegantly, he promises to send the declaration to the shop on Monday, I feel if not loved then at least respected by him, but on Monday he sends nothing, is not even in Prague any longer but has left.72

Not only did Hermann Kafka argue with his domestic staff and shout at them73 – he did so in Czech: ‘To je žrádlo. Od 12 ti se to musí vařit’ (‘This nosh is only fit for an animal. It must have been cooking since 12’).74 The choice of words may not be refined (žrádlo literally means ‘animal food’), but they are nevertheless Czech – because some of the Kafkas’ servants were Czech.

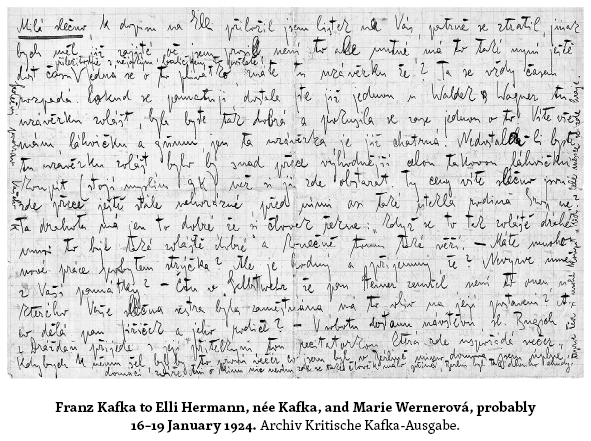

According to the Kafkas’ 1890 census form, their household included the maid and cook Františka Nedvědová and the servants Marie Zemanová and Anna Čuchalová, the latter also a nanny;75 in the 1900 census we find the names Božena Hořčičková and Anna Sedláčková, also ‘servants’; and in 1910 Anežka Ungrová. Judging by their names, places of birth and declared language we may assume they were all Czechs. A police report on another member of the household, however, the nanny Franziska Haas from Poděbrady, who in 1885 was called as a witness concerning the theft of a laundry-basket from the Kafka’s home,76 records her language as German. This was also the language of Elvira Sterk, Franz’s sisters’ governess, who worked for the Kafkas until 1902.77 By then the ‘French girl’ Céline (or Josephine) Bailly from Monthiers en Bresse in Belgium78 had also joined the household. And in early October 1902 the Kafkas engaged a new Czech governess, Anna Pouzarová, who was recommended by friends of Hermann Kafka’s in Strakonice and stayed until October the following year.79 In around 1910 ‘slečna’ (‘Miss’) Marie Wernerová (1884–1941), whose family was Czech-Jewish,80 began working for the family, and by 1921 at the latest she was living with them.81 We know her dominant language was Czech, as both Franz Kafka and his mother addressed her in Czech when they wrote to her.82

A few lines of Czech written by her have been preserved, as well as one greeting in German. To Kafka’s sister Ottla David (who married the Czech Josef David) she adds at the end of letters from Franz and Julie: ‘Mnoho pozdravu [sic] zasila [sic] Marie Wernerová’ (‘Marie Werner sends many greetings’)83 and ‘Pozdravuji srdečně babičku Davidovou’ (‘Give Granny David my warmest wishes’)84. But in a PS on a letter to the German-speaking family of Elli, née Kafka, and Karl Hermann she writes in German: ‘[Mit] besten Grüße[n] Fräulein / Marie Wernerova’.85

So Hermann Kafka’s declaration in the census that Czech was commonly used in his family was correct. And considering that respondents were only allowed to declare one of the two official languages, his decision was quite understandable, given the dominance of Czech in the city administration and the politicization of the whole language question. A ruling by the Administrative Court that the language declared by a person in the census has no bearing on their national identity, and is therefore not binding when it comes to their children’s schooling,86 tells us, first, that information provided in the census was not anonymous and, secondly, that interpretations of such data could if necessary be challenged in court. As Kurt Krolop’s detailed case study of the Feigl family shows, the information people supplied in the census could be far from authentic and may have been influenced by the ethnic setting in Prague, which at the time was dominated by Czechs.87 Nevertheless, the number of Jews in Bohemia who declared Czech as their common language grew from one third in 1880 to 50% in 1890. Conversely, the number of Jews in Prague who claimed to be German-speakers fell from 74% in 1890 to 45% in 1900. This shift in language loyalty can, but does not have to be understood in terms of perceptions of national identity. Such a massive statistical shift cannot be explained in terms of migration from the Czech and German areas in Bohemia alone.88

Let us return to Hermann Kafka’s relations with the Czech-Jewish movement. In favour of his involvement, some have invoked the supposed Czech origins that they claim predestined him linguistically, as he ‘spoke Czech better than German’.89 But even that is disputable. Remember that Hermann Kafka corresponded with his bride-to-be in German, and that after their marriage in September 1882 he ensured German was the family’s first language. As for his own knowledge of German, suffice it to say that in 1893 he worshipped in a synagogue where we know that the service, or part of it, was held in German. That is why I think we can dismiss Wagenbach’s assumption that the presence of Czech in the Kafka family was also decisive in matters of religion.

ANTISEMITISM AND ZIONISM

In the 1890s and the period around the elections to the Reichsrath, the ongoing nationality dispute between Czechs and Germans was accompanied by a militant antisemitism.90 The anti-Jewish riots in Kolín following the murder of a Christian girl in 1893,91 the inflammatory campaign in the Czech and German press around the Dreyfus affair in 1895, the pogroms in Prague and in Czech and German provinces when the Badeni reforms were introduced (and then abolished) in 1897, the Hilsner affair in 1899 – these were milestones in a gradual advance of antisemitism in Bohemia that also found support in political parties. Some Young Czech politicians resurrected the idea of a national anti-Jewish conspiracy that had already found expression in, for instance, Jan Neruda’s pamphlet ‘For Fear of Jewry’ (1870);92 pursued a policy of economic boycott; and interpreted social conflicts in ethnic (anti-German, anti-Jewish) terms. This tendency was personified by Václav Březnovský (1843–1918) and Karel Baxa (1863–1938), the Prague counterparts of the anti-Czech and antisemitic Viennese politician Karl Lueger (1844–1910). Georg von Schönerer (1842–1921) with his Pan-German party was by no means the only one to play the anti-Jewish card.93

Against this background it is hardly surprising that between 1890 and 1910 the number of Jews in Bohemia and Moravia fell by 10% through identity management and emigration.94 An alternative response was active Jewish nationalism and the creation of Zionist associations, through which assimilated Jews (albeit hesitantly at first) signed up to the ideas of Theodor Herzl, who in 1896 had published The Jewish State: Proposal for a Modern Solution for the Jewish Question, in 1897 organized the Zionist Congress where national Jewish associations joined forces in the World Zionist Organization, and whose Old New Land (1902) and diaries Kafka read.95

It was only gradually, however, that the idea of a secular Jewish national movement gained widespread support. Orthodox and assimilated Jews were opposed to Herzl’s political Zionism, and a Zionist congress planned in Munich had to be moved to Basel at the last moment due to resistance from the Jewish community in Munich.96 Brod, writing with hindsight, saw the tension between the assimilation and the re-ethnicization programs not only as a generational, but also as a polarizing social conflict between the grande bourgeoisie and the socialists,97 though he failed to distinguish between the various strands of socialism. Apart from the political Zionists, for whom the solution of the Jewish question lay in the founding of an internationally guaranteed and recognized secular Jewish state with its own territory and autonomous economy (Theodor Herzl), there were also the cultural Zionists (Ahad Ha’am, Martin Buber) who emphasized the spiritual, moral and cultural regeneration of the Jewish nation. In practice these two main blocks were sub-divided and modified into all manner of groupings, both political and cultural.

In this context Kilcher points to the distinct roles of Yiddish as the language of the Jewish diaspora in Eastern Europe, and Hebrew as the language of the Judaic tradition and revival.98 It should not be overlooked that the language question, which particularly in the Habsburg monarchy was hotly debated, also played a key role in crystallizing modern Jewish identity. Hugo Bergmann, for instance, believed that ‘a Zionist student who can’t speak Hebrew is a contradiction in terms’99 – a clear echo of Herder’s idea of the language-nation, or the Czech revivalist Josef Jungmann’s watchword ‘a Czech is one who not only thinks in Czech but speaks it’.100 Shumsky deals with the role of discourse on monolingualism and bilingualism in Bohemia for Jewish national conception for Palestine.101

Antisemitism and reactions to it also affected the universities. In Prague alone, the Teutonia student fraternity (or ‘Burschenschaft’) was formed in 1876, the Ghibellinia in 1880 and, at the German part of the already divided Prague University, the Germania (which barred Jews from membership) in 1891.102 In 1899 Prague Jewish students set up their own league, Bar Kochba, named after the leader of the Jewish uprising against the Roman emperor Hadrian. Bar Kochba, which grew out of the Makabäa society founded in 1893, was led in 1903–04 by Kafka’s schoolmate and friend Hugo Bergmann (1883–1975), who visited Palestine in 1910 and later became the founder the Jewish National and University Library in Jerusalem and rector of the Hebrew University (1936–38). Bergmann left for Palestine in 1920, and in 1923 we find him trying to persuade Kafka to settle there too.103 But Bergmann’s brand of cultural Zionism, which embraced the ideas of both Martin Buber and Ahad Ha’am and strove for a balanced relationship with Czechs and Germans alike,104 was too conciliatory for many students. Dissatisfied, a group led by Robert Neubauer, Jakob Fraenkl, Julius Löwy and Ernst Gütig founded Barissia with the aim of defending Jewish interests more militantly.105 In 1907, at a time of heightened nationalist tensions before the first general parliamentary elections, Franz Steiner launched the weekly Selbstwehr (Self-Defence) which, under the editorship of Leo Herrmann, had through his person close links with Bar Kochba. From 1913 its editor-in-chief was Siegmund Kaznelson (1893–1959), from 1917 (briefly) Nelly Thoeringer, and from 1919 until 1938 the paper was run by Kafka’s friend Felix Weltsch (1884–1964). During and after the First World War, Kafka – thanks to Brod and Weltsch – regularly read Selbstwehr.106 That and publications such as the Jüdische Rundschau (Jewish Review),107 along with his correspondence and conversations with both Brod and Weltsch, were Kafka’s main but by no means only sources of information about the Zionist movement of his day.108 He read books and articles by Martin Buber, Ahad Ha’am and other authors – in German, Yiddish and Hebrew.

Many members of Bar Kochba were pupils at Czech grammar schools or students at Czech universities and colleges, and some were at first closely involved in the Czech-Jewish movement.109 In 1909 a group of Czech-speaking students established the Zionist Spolek židovských akademiků Theodor Herzl (Theodor Herzl Association of Jewish Academics). Tellingly, it was intended for ‘Jewish academics of Zionist orientation’ rather than ‘Czech academics of Jewish origin’ (as an equivalent organization had been named in 1876), reflecting the formation of a new Jewish intellectual community of the time.

The formation of the Zionist movement had been discussed in Masaryk and Herben’s Čas (Time) as early as in 1898. Masaryk was sympathetic to Zionism and as president he even visited a Jewish settlement in Palestine.110 It was also thanks to him that Jews in democratic Czechoslovakia received proper recognition and were granted full rights as a national minority in the 1920 constitution.111 Equally, the new democratic values were respected by the Zionists, who felt that the program of linguistic, cultural and political assimilation represented by the Czech-Jewish movement was outdated and campaigned against it.112

But declared equality before the law is one thing; antisemitic prejudice in reality is quite another. And that showed little sign of disappearing, either in Prague or in other parts of Czechoslovakia. In 1918 and 1920 there were a number of anti-Jewish demonstrations.113 In 1920 Kafka mentions reading about anti-Jewish protests in Venkov, and in a letter to Milena Jesenská (17–19 November 1920) he reports hearing a derogatory Czech phrase in the street: ‘I recently heard someone call the Jews a ‘prašivé plemeno’ (mangy breed)’.114 And even after Kafka moved to Berlin he still came across antisemitic reactions.115

FRANZ KAFKA AND YIDDISH

Kafka went to see the Yiddish folk theatre from Lvov on 1 and 4 May 1910, but it was the profound impression made by Yitzchak Löwy’s ‘Original Jewish Company’, which Kafka first saw on 5 October 1911, that inspired and initiated his ‘Jewish rebirth’.116

I love the Yiddish theatre; last year I may have gone to twenty of their performances, and possibly not once to the German theatre.117

One factor was undoubtedly the personality of Löwy himself, who had left his family home in Warsaw to pursue his artistic career. Kafka even goes so far as to say that he would gladly prostrate himself ‘in the dust’ before him in admiration.118 Through Löwy (Kafka’s mother’s namesake), he gained an insight into the spiritual world of the Eastern Jews, the Kabbalah and – as we see in his ‘Character sketch of small literatures’ – modern Jewish literature,119 which was to influence his own writing. Thus Binder sees a link between Goldfaden’s Yiddish novel Two Bold Lads and the two ‘helpers’ in Kafka’s Trial and Castle.120 Of course Kafka read the Jewish press, too: in 1912 he took out subscriptions to Palästina and Jüdische Rundschau (Jewish Review), and he was a regular reader of the Jewish monthly Ost und West (East and West). He also familiarized himself with Hasidic literature: Wolf Pascheles (Sippurim), Martin Buber, Micha Berdyczewski (better known as Bin Gorion), Alexander Elisaberg, Fritz Mordechai Kaufmann and others.121 For his ‘Introductory speech on Jargon [Yiddish]’ (see below) Kafka read Meyr Isser Pines’ Histoire de la Littreture judéo-allemande (1911).122

During this period Kafka believed that in the traditional Yiddish folk theatre he could find Jews who still had their ‘own’ language and cultural identity and still lived in a natural ethno-national community. In contrast, the Jewish environment he lived in had become largely assimilated, in terms of both language and religion. Nonetheless, it is clear from his diary that he doubted to what extent a Jew can ever comprehend his world through a ‘foreign’ language:

Yesterday it occurred to me that I did not always love my mother as she deserved and as I could, only because the German language prevented it. The Jewish mother is no ‘Mutter’, to call her ‘Mutter’ makes her a little comic (not to herself, because we are in Germany), we give a Jewish woman the name of a German mother, but forget the contradiction that sinks into the emotions so much more the heavily, ‘Mutter’ is peculiarly German for the Jew, it unconsciously contains, together with the Christian splendour Christian coldness also, the Jewish woman who is called ‘Mutter’ therefore becomes not only comic but strange. Mama would be a better name if only one didn’t imagine ‘Mutter’ behind it. I believe that it is only the memories of the ghetto that still preserve the Jewish family, for the word ‘Vater’ too is far from meaning the Jewish father.123

While the Jew is losing his own, old language (Hebrew) just as he has lost his own homeland, in the new language (German) – an idiom shaped by the Christian world-view – he can find no new home. The German Mutter and German Vater are not the same as the Jewish mother and the Jewish father. These are better reflected in the appropriated ‘hybrid’ Yiddish múter and fóter (colloquially, mame and tate) which neutralize ‘the Christian splendour and coldness’. The German Familie is not the Yiddish mišpoche, although the similarity between Mutter and múter and Vater and fóter tells us they are closely related. This is connected with a cultural relativization of German, the language Kafka and his friends had been hearing all their lives from their ‘un-German mothers’.124 Although German is his ‘mother tongue’ or ‘natural language’,125 Kafka considers himself ‘half-German’126 and he cannot fully grasp his world with it. German is his mother tongue, yet still he feels its foreignness when he tries to name his mother in it; he is at home in German, yet still – whether he is on the inside looking out or on the outside looking in – he feels a stranger in it, as we will see in the chapter on ‘mauscheln’ or ‘mumbling’, as Yiddish and the Jews’ distinctive way of speaking German were dismissively referred to by German speakers.

Yiddish, which as the ‘hybrid’ language of the diaspora signals the loss of Hebrew, may nevertheless be a way of overcoming that loss, as it is the language of a living ethno-national community. Kafka’s fascination with Yiddish – evidenced by his ‘Introductory speech on Jargon [Yiddish]’ given at an evening organized by Yitzchak Löwy on 18 February 1912127 – is aesthetically motivated. He speaks of the astonishing sense of estrangement from what is close to you, from what you know and own: You can’t understand a word and yet – if you know German – you can understand it all. This tension between the alien and the familiar, the distant and the near, which makes Yiddish untranslatable into German, is what intrigues Kafka and sets him off on an ‘ethnographic’ study of Yiddish:

Because you can’t translate Jargon into German. The connections between Jargon and German are so delicate and meaningful that they would rupture completely if you tried to translate Jargon back into German, that is, you wouldn’t be translating Jargon, but something non-existent. Translating into French, for example, you can convey Jargon to the French; translating it into German you destroy it. ‘Toit’, for example, is certainly not ‘tot’, and ‘Blüt’ is in no way ‘Blut’.128

Objectively, of course, ‘toit’ does mean ‘tot’ (‘dead’), and ‘blüt’ or ‘blut’ does mean ‘Blut’ (‘blood’). But the Yiddish words have – like ‘múter’ and ‘fóter’ – different associations and a different aesthetic value, besides their emotional one, which gain depth and breadth when set against the German. Their foreign sound – the ‘Hasidic melody’ of Yiddish – renders familiar words unfamiliar to the Central European listener brought up in a non-Yiddish setting, placing them, with new connotative value, in a different spiritual and social context of which it becomes an important part, if not the very precondition and (textual) objective for the reception of original Yiddish folk theatre and, as Buber saw it, the source of its creative power.

It is no accident that Kafka in his ‘Character sketch of small literatures’, in which he notates the findings of his ‘ethnographic research’, also touches on Czech. For the Czechs, too, at that time still a people without a state, it was equally true that a nation’s backbone and instrument of self-definition is its literature, written in its own language. Giving Czech ‘a voice’ and an ethnographic canon was a project that satisfied both the aesthetic needs of the time and the nationalist agenda. We find something similar with Yiddish, which is seen as a ‘folk’ language (‘Volkssprache’) whose ‘vitality’ becomes an aesthetic value in itself and thus a substitute for a political program – as was the case with Czech.

Thus Kafka’s fascination with ‘jargon’ goes beyond the merely aesthetic: for him Yiddish is the embodiment of ‘unity’, ‘strength’ and ‘self-confidence’:

But once Jargon has you in its grip – and Jargon is everything: word, Hasidic melody and the essence of the Eastern Jewish actor himself – then you can forget about your former peace. Then you will get to feel the true unity of Jargon, so strongly that you will be afraid – not of the Jargon but of yourself. You wouldn’t be able to bear this fear alone, if the Jargon didn’t also fill you with self-confidence, which withstands the fear and is even stronger than it.129

For Kafka, the vital ‘unity’, ‘strength’ and ‘self-confidence’ are rarely to be found outside the context of Yiddish:

The second poem is by Frug and is called Sand and Stars. / It’s a bitter interpretation of a biblical promise. It says we shall be as the sand on the seashore and the stars in the heavens. Well, we’ve already been trampled on like sand. When will the bit about the stars come true?130

For Kafka Yiddish is also a counterweight to the loss of cultural and social bonds. Its strength lies in the fact that the Eastern Jews live in unity with each other; they neither deny nor doubt their identity but actively espouse it. Max Brod, too, felt the ‘life’ in Yitzchak Löwy’s folk theatre, whereas in the Bar Kochba academic society he saw only ‘theory’.131 For Hebrew-oriented Zionists, however, and for assimilated Prague Jews, any identification with Eastern Judaism and Yiddish might – in all but a few cases132 – be taken as a provocation.133 The first regarded Yiddish as a language of diaspora; the second saw its use as a mark of cultural reorientation and regression to a German ‘jargon’.

In truth not even Kafka’s parents – especially his father – had much understanding for their son’s enthusiasm. They certainly did not attend a recital evening that he organized in the Jewish Town Hall, where he gave an introductory lecture.134 The objective of the event was to raise money for Löwy’s troupe, but in this it failed owing to a lack of interest among the Prague Jewish community it had aimed to address and convert. Kafka’s support of Löwy could be seen as a demarcation line separating him from the world of his father or, more exactly, from the culture of assimilation. Kafka even writes of a ‘lack of any kind of solid Jewish ground under [his] feet’.135

Rather than psychology I prefer in this case the realization that this father complex, from which so many derive intellectual nourishment, concerns not the innocent father but the father’s Judaism. Most people who started writing German wanted to get away from Judaism, mostly with their father’s vague consent (it was this vagueness that was so offensive); they wanted to but, with their hind feet still stuck in father’s Judaism, their front feet could find no new ground. The resulting desperation was their inspiration.136

Löwy and his company were the embodiment of values that Kafka and some of his friends found lacking in their fathers. Yiddish seemed to offer an alternative way of being Jewish in everyday life. Jiří (Georg) Mordechai Langer, a friend of Franz Kafka, to whom we shall return in the chapter ‘Kafka’s Czech reading in context’, went to an Eastern yeshiva to learn more about Judaism and live his Jewish dream.137 They, the sons, rejected assimilation and attempts at advancement in bourgeois society by those Jewish families that had ‘gone cold’.138 He later wrote to his father:

Later, as a young man, I could not understand how, with the insignificant scrap of Judaism you yourself possessed, you could reproach me for not making an effort [. . .] to cling to a similar, insignificant scrap. It was indeed, so far as I could see, a mere nothing, a joke – not even a joke. Four days a year you went to the synagogue, where you were, to say the least, closer to the indifferent than to those who took it seriously [. . .]139

This could explain his commitment to the ‘zealous’, ‘lived’ Jewishness that arrived in Prague in the person of Yitzchak Löwy and his theatre company, who put across their message in a ‘Jewish’ language used throughout a large ethno-national community: Yiddish.140 But the assimilated Jews of Prague saw Löwy and his troupe, with their outlandish seeming language and customs, more as provocateurs than as models to be emulated. And provocative is clearly what the alienating otherness of Yiddish was meant to be, jolting the community out of its daily cultural certitudes. How else are we to understand Kafka’s formulation in his lecture: ‘you will be afraid – not of the jargon but of yourself’?141

This was not the only issue that drove a wedge between father and son. The son might lose patience with the father’s caution in matters of language, criticising not only his assimilation in terms of language and religion, but also his passive involvement in the Czech-German language struggle by declaring himself and his family as Czech in a city which at the time was dominated by Czechs – although such caution was quite understandable given the intensity of the language war. So it is not surprising that Kafka’s authorial subject expresses the ‘The wish to be a Red Indian’ (1912), to remove himself from the public sphere,142 to ride only one horse, not try and straddle two, he stops short, but does not become really an active Zionist like Max Brod.143 Indeed, Kafka described the 11th Zionist Congress, which he briefly attended on 8 September 1913 while on a business trip to Vienna, as ‘an entirely alien event’.144 But, as the irony in the following passage makes clear, this was very far from the lack of involvement that characterized his father, or one Prague Jew

who until the overthrow [1918] was (in secret) a member of both the German Club Deutsches Haus and the Czech Club Měšťanská beseda, who has only now succeeded, through various connections, in getting himself dismissed from the German Club (his name was deleted) and had his son transferred to the Czech Realschule [secondary school], [where] ‘he will learn neither German nor Czech, only how to bark’. Naturally, his choice was governed ‘by his faith’.145

Yet not even Yiddish provided lasting certainty: the language of diaspora was not the rock on which a renewed Jewish culture and Jewish spirit could be founded. Kafka became aware of this in the language of Yitzchak Löwy, whose ‘language veers between Yiddish and German, inclining more to German’.146

FRANZ KAFKA AND HEBREW

In time Kafka’s enthusiasm for Yiddish waned. In 1916 and 1917, the year in which Kafka wrote ‘A page from an old manuscript’, the Prague Jewish community was struggling to cope with a large influx of Eastern Jews fleeing from the front in Galicia.147 Partly on account of this synchronicity, Binder sees the story as an allegorical portrayal of the Eastern Jews: without a language of their own, or rather without any language at all (the ‘nomads’ communicate like ‘jackdaws’ – kavka [kafka] in Czech – maybe a reference to the fact that the Jew Kafka also had no Jewish language), without culture (they feed on raw meat), and without a plan (they are drawn to the imperial palace but, unable or unwilling to attack it, stop at its gates). Before them are the massive walls of the palace. The inability of the nomads to penetrate the palace, which can be equated with the Jewish temple and thus with the halacha and Hebrew, may be taken as Kafka’s reorientation from Yiddish to Hebrew. Yiddish as the language of the Eastern Jews is now associated – for Kafka too, apparently – with adaptability, assimilation, diaspora.148 Describing a meeting with an Eastern rabbi from Belz, he speaks of a ‘strange mixture of enthusiasm, curiosity, scepticism, approval and irony’.149 Brod dismisses Western apologists of ‘Judaism’ as ‘Western lutenists’, while Kafka eventually rejects Buber, calling his books ‘disgusting’.150 On the evidence of ‘An old manuscript’ it would seem that by 1917, or perhaps early 1918, Kafka’s ‘Yiddish phase’ had come to an end,151 although the story also admits of other interpretations as we shall see in the chapter ‘Kafka’s organic language’. It also raises the question as to which ‘side’ is shown in a more critical light: the nomads who, with no grammar, no culture and no agenda, come pouring pell-mell into the empire; or the local population who, like the narrator himself, have no means of resisting the intruders and despite their cultural ‘superiority’ can only respond with words – by recounting the horrific story of how a live ox was brutally hacked to pieces before their eyes. For Kilcher this suggests Kafka was still on the side of ‘yiddishism’.152

Yet we do have other evidence of Kafka’s shift from Yiddish to Hebrew at that time, at least in a linguistic sense. In May 1917 – possibly ‘inspired’ by Gershom Scholem153 – Kafka began taking a more active interest in Hebrew, which as recently as 1913–14 had become the dominant language in Palestine.154 And although he soon discontinued his Hebrew lessons for health and personal reasons, he resumed them the following year. His teacher was a young woman named Puah Ben-Tovim, who came to Prague ‘on Hugo Bergmann’s advice’155 in 1922 and became an object of general awe as she belonged to the first generation brought up in Jerusalem with Hebrew as their native language:

The news that she wishes to sing spreads immediately, and soon they come streaming in.156

Kafka, who was never free of ‘the not unjustified fear of disturbances’,157 was fascinated by the sense of conviction that emanated from Puah and her language.158 In the dainty person of Puah – the ‘only’ one in Prague who speaks and lives ‘proper’ Hebrew, and whom Kafka’s mother asked to teach her son159 – we may discern the prototype of little, ‘dainty’160 Josephine, the central figure in the short story ‘Josephine the Singer, or The mouse people’ (March 1924),161 who like Puah has an extraordinary way of ‘singing’:

Anyone who has not heard her does not know the power of song. There is no one her singing does not enthral, which, given that as a species we are not fond of music, is saying a great deal.162

Kafka is not only talking about the teaching of Hebrew, with its emphases on singing and song; he is also criticizing the assimilationists of that time, who are in their ‘being’, as we read a few lines later, ‘not fond of’ singing. Yet Hebrew (‘singing’), which by Kafka’s day the average Central European Jew had stopped using or forgotten, apart from the few fragments he heard in the synagogue, is a fundamental attribute of ‘The [. . .] People’ – even if it is only ‘squeaking’ in Jargon:

So is it in fact singing at all? We may be unmusical but we have our traditions of song; singing was not unknown to our people in the olden days; it is mentioned in legend, and there are even songs that have come down to us, though of course no one can sing them anymore. [. . .] We all squeak, though of course nobody thinks of passing it off as art; we squeak without paying any attention to the fact, indeed without being aware of it, and there are many among us who do not even realize that squeaking is one of our distinguishing characteristics.163

The narrator may tell us that the transition from singing to squeaking is barely discernible, yet still the two are construed as opposites, Josephine’s singing (the Hebrew of Puah the ‘new Jewess’) being contrasted with the squeaking of ‘the mouse people’, whereby the ‘people’ in the discourse of the day – and thus also for Kafka – was associated with Yiddish: ‘Anyway, the fact is that she denies any connection between her art and squeaking’.164

This is more than a matter of music or language. For even though the difference between squeaking (Yiddish) and singing (Hebrew) is very slight, if discernible at all, for the mouse people Josephine’s singing means salvation:

In a grave political and economic situation her singing supposedly constitutes nothing less than our salvation; if it does not banish misfortune, at least it gives us the strength to bear it. She does not say so, either directly or indirectly, she does not talk much at all, she is silent compared with us chatterboxes, but it flashes from her eyes, and on her closed lips [. . .] Whenever there is bad news [. . .] she immediately stands up, whereas most of the time she spends lying tiredly on the floor, she stand up and cranes her neck and tries to embrace her whole flock with her gaze as the shepherd does before the storm.165

The question remains whether in learning Hebrew Kafka was necessarily embracing ‘hebraism’. In Josefine, singing – like Hebrew in the discourse of the day – does indeed represent more than a new quality of language and – in as far as it replaces Yiddish ‘squeaking’ – of Judaism itself, which sees in Hebrew a renewal of its age-old ‘being’ and collective self-awareness; on the other hand, there is the word ‘supposedly’ and the distancing which that implies. Nonetheless, in Kafka’s study of Hebrew, in his life with Dora with her conservative Hasidic family background where both Yiddish and Hebrew were spoken,166 and in his attendance at courses and lectures at the Institute for Jewish Studies167 we can see a search for the ‘being’ mentioned at the start of this chapter, and a continual reaching out to the land he ‘yearned for’.168

1 Franz Kafka, The householder’s concern. In: Franz Kafka, Stories 1904–1924. Translated by J. A. Underwood, with a foreword by Jorge Luis Borges. London: Abacus 1995, p. 206.

2 Pavel Trost, Franz Kafka und das Prager Deutsch (Franz Kafka and ‘Prague German’). Germanistica Pragensia 2 (1964), 29–37, here p. 33. See also Pavel Trost, Der Name Kafka (The proper name Kafka). Beiträge zur Namenforschung 18 (1983), No. 1, 52–53.

3 See Hugo Siebenschein, Česko-německý slovník (Czech-German Dictionary), vol 2. Prague: Státní pedagogické nakladatelství 1983, p. 700f.

4 For the formation of this group of Czech words, see Dušan Šlosar, Slovotvorba (Word Formation). In: Petr Karlík – Marek Nekula – Zdenka Rusínová (eds), Příruční mluvnice češtiny (Handbook of Czech Grammar). Prague: Nakladatelství Lidové noviny 1996, pp. 109–225, here p. 146.

5 Another interpretation of the word Odradek sees a possible analogy with the proper name Odkolek (also the name of a firm). See Johannes Urzidil, Von Odkolek zu Odradek (From Odkolek to Odradek). Schweizer Monatshefte 50 (1970), No. 1, pp. 957–972. There is also the village of Ostředek near Prague, though it is unlikely to have any significance for Kafka.

6 See Kurt Krolop, Zu den Erinnerungen Anna Lichtensterns an Franz Kafka. Ke vzpomínkám Anny Lichtensternové na Franze Kafku (On Anna Lichtenstern’s recollections of Franz Kafka). Germanistica Pragensia 5 (1968), pp. 21–60.

7 Franz Kafka, Kafka’s Selected Stories. Translated and edited by Stanley Corngold. New York, London: W. W. Norton 2005, p. 12.

8 First published in Max Brod, Im Kampf um das Judentum. Politische Essays (In the Struggle for Jewishness: Political Essays). Vienna, Berlin: R. Löwit Verlag 1920, p. 15. See also Marek Nekula, Theodor Lessing und Max Brod. Eine mißlungene Begegnung (Theodor Lessing and Max Brod: A failed encounter). In: brücken. Germanistisches Jahrbuch Tschechien – Slowakei. NF 5 (1997), pp. 115–122, here p. 118.

9 Franz Kafka, Ein Landarzt und andere Drucke zu Lebzeiten (A Country Doctor and Other Texts Published in his Lifetime). Ed. by Hans-Gerd Koch. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1994, p. 222.

10 Jacob Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch (German Dictionary). Vol. 10. Leipzig: Verlag von S. Hirzel, 1919, column 221.

11 Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch, vol. 16, 1954, column 1320.

12 Franz Kafka, Kafka’s Selected Stories, p. 72.

13 See August Stein, O židovské obci v Čechách (On the Jewish Community in Bohemia). In: Kalendář česko-židovský na rok 1887/1888, pp. 131–165. See Michael K. Silber, Josephinian reforms. In: The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (online).

14 The names are not exclusively German. Besides the Kafkas, we can also find in Osek a family named Holub (in fact the headstone in the cemetery bears a Germanized form of the name, ‘Hollub’), suggesting that Czech names and sobriquets soon became commonplace – a reaction against the ‘unintelligibility’ of Hebrew and Yiddish names and of the Hebrew script in general. More see Jiří Kuděla, Germanizace židovských jmen v Čechách (Germanization of Jewish names in Bohemia). Židovská ročenka, 2005, pp. 29–39.

15 See J. S. Kraus, Německo-židovské školy v Čechách (German-Jewish schools in Bohemia). In: Kalendář česko-židovský na rok 1882/1883, pp. 117–125.

16 See Kafka’s family tree in Anthony Northey, Kafkas Mischpoche (Kafka’s Mishpoche). Berlin: Wagenbach 1988; Anthony Northey, Die Kafkas: Juden? Christen? Tschechen? Deutsche? (The Kafkas: Jews? Christians? Czechs? Germans?) In: Kurt Krolop – Hans Dieter Zimmermann (eds), Kafka und Prag. Colloquium im Goethe-Institut Prag. 24.–27. November 1992 (Kafka and Prague: Colloquium in the Goethe Institute in Prague, 24–27 November 1992). Berlin, New York: de Gruyter 1994, pp. 11–32.

17 See Northey, Die Kafkas, p. 12, and Alena Wagnerová, „Im Hauptquartier des Lärms.“ Die Familie Kafka aus Prag (‘In the Headquarters of Noise’: The Family Kafka from Prague). Berlin: Bollmann 1997, p. 29f.

18 See Johann Gottfried Sommer, Das Königreich Böhmen statistisch-topographisch dargestellt (The Kingdom of Bohemia from a Statistical and Topographical Perspective). Vol. 8, Prague 1840, p. 103.

19 See Albert Kohn, Die Notablenversammlung der Israeliten Böhmens in Prag, ihre Berathungen und Beschlüsse. Mit statistischen Tabellen über die israelitischen Gemeinden, Synagogen, Schulen und Rabbinate in Böhmen (The Prague Compendium of Notable Jews in Bohemia, their Sessions and Resolutions. With Statistical Tables on Jewish Municipal Authorities, Synagogues, Schools and Rabbinates in Bohemia). Vienna: Verlag von Leopold Sommer, 1852, 411ff; quoted in Northey, Die Kafkas, p. 12.

20 My thanks to Pavla Kostková of the Prague Land Survey Office and Jindřich Zdráhal of the Strakonice Land Registry for providing copies of land records and maps from 1837 to 1914.

21 Based on the traditional names of the cottages in Jewish Street, where in 2000 I interviewed a number of men (average age 70) who had been born, grown up and lived in Osek. This is not a fully reliable source, of course; still, place names lodged in the memory do tell us something.

22 See Wagnerová, „Im Hauptquartier des Lärms“, p. 30.

23 See Northey, Die Kafkas, p. 13.

24 See Hillel J. Kieval, The Making of Czech Jewry. National Conflict and Jewish Society in Bohemia, 1870–1918. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press 1988.

25 Franz Kafka, Zur Frage der Gesetze und andere Schriften aus dem Nachlaß in der Fassung der Handschrift (On the Question of Laws and other Literary Remains based on the Handwritten Manuscripts). Ed. by Hans-Gerd Koch. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1994, p. 44. Kafka recalls Hermann Kafka calling Max Brod ‘einen meschuggenen ritoch’. Julie Kafka, in a letter from Perštejn (Pürstein), uses the word ‘Mišpoche’; in another letter dated on 12 July 1925, she writes ‘Mischpoche’ (Bodleian Library, Oxford). See Franz Kafka, Tagebücher (Diaries). Ed. by Hans-Gerd Koch, Michael Müller, Malcolm Pasley. Vol. 1. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1990, p. 214. See also Northey, Kafkas Mischpoche.

26 Northey, Die Kafkas, p. 13.

27 See Seznam míst v království Českém (Index of Villages and Towns in the Kingdom of Bohemia). Prague: Místodržitelská tiskárna (Governor’s Printing Press) 1907, p. 503.

28 Northey thinks this public servant was Jakob Kafka, which would mean that German was spoken in the family. Northey, Die Kafkas, p. 18.

29 See Franz Kafka, Briefe 1913 – März 1914 (Letters 1913 – March 1914). Ed. by Hans-Gerd Koch. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 2001, p. 39.

30 For the situation in the Kafka household see Northey, Kafkas Mischpoche.

31 At the same time there were similar incidents in Prague. See Kieval, The Making of Czech Jewry, p. 18.

32 Franz Kafka, Dearest Father. Stories and Other Writings. Translated by Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins. New York: Schocken 1954, p. 173.

33 Jan Křen, Konfliktgemeinschaft. Tschechen und Deutsche 1780–1918 (Conflictive Community: Czechs and Germans 1780–1918). 2nd edition. Munich: Oldenbourg 2000, p. 111.

34 For the school in Osek, see also Wagnerová, „Im Hauptquartier des Lärms“, p. 40.

35 Hugo Hermann, In jenen Tagen (In those Days). Jerusalem: self-publication, 1938, p. 222. See also Krolop, Zu den Erinnerungen Anna Lichtensterns an Franz Kafka, p. 41.

36 See Rudolf M. Wlaschek, Juden in Böhmen. Beiträge zur Geschichte des europäischen Judentums im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert (Jews in Bohemia: Contributions to the History of European Jewry in the 19th and 20th Century). Munich: Oldenbourg 1997, p. 29.

37 These letters from 1882, along with his German notes on Julie Löwy’s letters made in 1917, 1926 and 1929, are in the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

38 See for example the comparative tables of Czech spelling rules in František Čapka – Květoslava Santlerová, Z dějin vývoje písma (From the History of the Evolution of Writing Systems). Brno: Masarykova univerzita 1998.

39 Hermann Kafka to Julie Löwy, 9 June 1882, 6 July 1882, 11 August 1882; Julie and Hermann Kafka and Marie Wernerová to Elli and Karl Hermann, 24 March 1926. Bodleian Library, Oxford. – Hermann Kafka generally used German topographical names such as Böhmisch Leipa for Česká Lípa, so that his Tabor (Czech Tábor, German Tabor) may simply be the (correct) German spelling. Budyně nad Ohří is often called simply Budyně or Budyň. Antonín Profous, Místní jména v Čechách. Jejich vznik, původní význam a změny (Bohemian Toponyms: The Origins and Changes of their Meanings). Vol. 1. Prague: ČSAV 1954, p. 230.

40 Kafka, Tagebücher, p. 323.

41 Kafka, Zur Frage der Gesetze, p. 29.

42 For example, Hermann Kafka mentions Vienna in a letter to Julie Löwy written in 1882 (Bodleian Library, Oxford). For the Prague milieu, see inter alia Northey, Die Kafkas; or Marek Nekula, „. . .v jednom poschodí vnitřní babylonské věže. . .“ Jazyky Franze Kafky (‘. . . on one Floor of the Inner Tower of Babel. . .’: Franz Kafka’s Languages). Prague: Nakladatelství Franze Kafky 2003. For a more general study of Prague, see Jiří Pešek, Od aglomerace k velkoměstu. Praha a středoevropské metropole 1850–1920 (From an Agglomeration to the Capital City: Prague and Central European Capital Cities 1850–1920). Prague: Scriptorium 1999.