FRANZ KAFKA’S LANGUAGES

In this chapter I shall discuss the languages that Franz Kafka used in his everyday life and learned in school or in other contexts. Here I shall not be considering the place of languages in his fictional texts, for example the confused Babylonian languages in the story ‘The city coat of arms’, the language(s) used in the ‘Building of the Great Wall of China’, the jackdaw language of nomads in the story ‘A page from an old manuscript’, the language of jackals in the story ‘Jackals and Arabs’, the monkeyspeak in the story ‘A report to an Academy’, or the singing of Josephine and ‘squeaking’ of the mouse people in the story ‘Josefine, the Singer, or The mouse people’. Admittedly, these linguistically hybrid inventions – including Odradek – are interesting with regard to Kafka’s bilingualism and his and his family’s position between linguistically defined cultures, but in this chapter I aim to reconstruct Kafka’s language biography on the basis of his diaries, correspondence, school reports and other sources. I try to trace his acquisition and his family use of different languages in different everyday domains, as well as to identify the changing relevance of these languages in his life and the production of meaning associated with them. I also want to consider the relationship between Kafka’s use and view of them and their status in the Prague of the late Habsburg monarchy and the newly founded Czechoslovakia.

Given the role of German as Kafka’s first and lifelong dominant and literary language, this chapter may well seem to do it less than justice in terms of coverage: German is the last language I discuss in this chapter and I say more about Yiddish and Czech. On the other hand, I discuss Yiddish and Czech in their relationship to German – both from the point of view of language contact and from the point of view of bilingualism. This approach is intended to supplement and complement my treatment of these themes in my earlier monograph on Franz Kafka’s languages.

With respect to German, I argued in the relevant chapter of my monograph1 that it is wrong to see Kafka’s German as the ‘poor’, ‘sterilized’ ‘ghetto German’ of a Prague Jewish society isolated socially and in dialect2 and I tried to shift the perspective from ‘Sprachinselforschung’ (research on isolated languages) to ‘Stadtsprachenforschung’ (research on urban languages). I have also followed this line in other publications and in my project mentioned in the foreword.3 I argued that the doubts and deprecation expressed by Kafka and his contemporaries, as well as later essayists and German philologists, on the character of their German, had more to do with the tradition of fin-de-siècle scepticism about language in general than with Prague linguistic realities. Until 1918, when Kafka turned thirty-five, Prague was the centre of a bilingual, German-dominated Bohemia inside the Habsburg monarchy. This meant that Prague was the seat of Bohemian provincial institutions that were responsible also for the predominantly German-speaking ‘province’ and had used only German as the official language until 1880. This is reflected partly in Kafka’s professional agenda at the insurance company, involving frequent business trips to predominantly German-speaking regions outside Prague.4 Prague had its own German schooling system including the German university employing German staff, some of them from outside Prague and Bohemia, and drawing students from further afield than the German ‘province’ of Bohemia. Furthermore, Prague was a magnet for migration not only of Czechs from primarily Czech areas but for many years also for people from the German ‘province’, and even after 1918 from other German-speaking countries. Prague had close and intensive cultural connections with Vienna, Berlin, Munich and Leipzig, including not only guest theatre productions but also frequent readings and lectures. Prague cafés were full of German newspapers and journals; the newspaper Prager Tagblatt (Prague Daily News) was read further afield than Prague and its contributors were often drawn from German-speaking lands other than Bohemia. Last but not least, the second ‘Sommerfrische’ (summer resort) of the Kafka family was not far from Prague – 38 km by train. The fact is that German Prague was not linguistically or culturally isolated at all; on the contrary, it was a major and well-connected centre for German cultural and linguistic events.

In this context it is unrealistic to suppose that there was only one exclusive, unified and stable urban variety of ‘Prager Deutsch’ (Prague German), even though Kafka himself occasionally spoke of his German as ‘Prager Deutsch’ and some features of pronunciation and syntactic patterns typical for spoken German in Prague appear in his texts. The ‘Prague German’ of the time is better understood as a shorthand concept for a loose amalgam of several varieties of German used by various social and ethnic groups in different parts of the Prague agglomeration. As regards the standard of spoken and written German, Vienna was the primary model, although educated Germans in Prague also took note of the varieties of German written and spoken in other German cities such as Leipzig or Berlin. My approach in my earlier monograph was to emphasize Prague’s intensive contacts with and exposure to texts and people from the other German-speaking territories, but I nevertheless tried to point out elements, forms and structures specific to Kafka’s German, from the contemporary point of view, that correspond to the orthographic, morphological, syntactic and lexical idiosyncrasies of German in his territory and time. At the end of this chapter I shall briefly come back to these special features. They have already been and will be discussed in more detail in publications associated with the already mentioned project.5

German was then the ‘mother tongue’ of Franz Kafka,6 but which other languages are in play in the case of Franz Kafka? From the outside and at a distance, the answer seems simple enough: Czech and, to some extent, Hebrew. These are the languages that Kafka read and wrote and that left their mark on Kafka’s texts; these are also the languages that are usually discussed in regard to Kafka’s origin and faith. If we consider only the languages that Kafka learned from an early age, the list contains just German and Czech.

The list of languages grows, however, if we take a closer look and consider not just the languages that Kafka encountered at home, but those that he acquired at school and those to which he was exposed even if he did not use them actively. These evidently include English, which he mentioned in a job application form, and also Yiddish. At school Kafka came into contact with Latin, Greek, classical Hebrew and French in addition to Czech and German.

LATIN & GREEK

Latin and Greek, the languages of the ‘Bildungsbürgertum’ (educated middle to upper class), and German, were compulsory subjects in academic schooling, and were emphasized to a degree that today might seem excessive. Kafka took Latin throughout grammar school, for eight years altogether, with five to eight lessons a week. When he completed school, Kafka received a C for his final translation from Latin into German and a B for his translation from German into Latin. He also studied Greek for six years, from the third year of grammar school onwards, with four or five classes a week. Even though he earned a C in his final examination at the end of grammar school, he had sometimes been awarded with Bs.7 If we leave aside the history of Roman law that he studied at the Faculty of Law, or Rzach’s classes on the ‘Interpretation of Cicero’s speech Pro archia poeta’ and on legal terminology,8 Latin and Greek did not play a significant role in Kafka’s subsequent life. Nevertheless, it is hardly possible to read Kafka’s work adequately without knowing ancient mythology, as is evident from his short stories such as ‘The silence of the Sirens’, ‘Poseidon’ or ‘Prometheus’, as well as from the character’s name Momos in his novel The Castle and many other references.

FRENCH

In contrast to the ‘dead’ languages, French was required only from the fifth year of grammar school onwards, for a total of four years (with two lessons a week). Kafka regularly earned Cs in French, but he also encountered French after finishing his school lessons,9 both at home, thanks to Céline (Josephine) Bailly, a Belgian who worked there as a governess for the Kafkas in 1902,10 and when reading books by Gustave Flaubert and other French authors together with Max Brod11 as well as with Hedwig Weiler:

Please, come; just before your letter arrived I thought how lovely it would be for us to meet on Sunday morning and read that French book I am in the midst of reading (I have so little time at present) which is written in a chilling, yet tattered French, the way I love it. . .12

It is difficult to say if Kafka’s notes in German and Czech in the margins of Coursier’s French reference book on Conversation in French and German13 were made at this time, and to what extent Kafka used this book to extend his knowledge of French. After all, Kafka’s reference to the poverty of his French could have resulted from other – let us say lover’s – worries:

If he speaks exquisite French, then that is a significant difference between the two of us, and the fact he can see you a lot is a damned difference.14

In any event, Kafka claimed to have mastered French in his letter to the Workers’ Accident Insurance Company in Prague on 30 June 1908:

The applicant is proficient in German and Czech, both in spoken and written form, and has a command of French and to a certain extent of English.15

Kafka seems to have had little chance to use French and English actively at this time. Two years before, when he filled in a form from another insurance company, Assicurazioni Generali, containing questions such as ‘Do you know any other languages besides your native language? To what degree do you know them? Is your understanding of these languages merely passive, or are you able to use them while speaking or writing translations and articles?’ he wrote: ‘Czech, in addition to French and English, although I lack practice in the last two.’16

He did have some practice, however, for we know that Kafka, Max Brod and Willy Nowak attended French classes given by an unknown ‘Frenchwoman’ in the summer of 1910.17 Kafka also travelled to France with Max Brod in October 1910 and again in September 1911. Max’s brother, Otto, accompanied them on the first trip.

According to Max Brod’s records, Kafka also spoke Czech on one of these trips, but it sounded more like ‘Chinese’ to Parisians:

I know Hannovre street number 4, we first go to number 7. A woman in mourning dress invites us to come in. We first ask for information, and we begin to fall completely into a Prague way of behaving. She is more polite, delicate, witty and funny than the old ladies back home, who are almost stiff in their frustration, seemingly placed around such doors just to make the darkness thicker. In reply to the question, originally meant as a means of escape, as whether the ladies upstairs speak Czech as well, she begins to stutter in a humorous way: We don’t speak Cz-Cz-Cz-Czech – but we do like checks! – She starts listing the prices we have to pay upstairs and apologizes at the same time: ‘I am telling you quite openly.’ – She doesn’t understand ‘derangement’, a term with which we were familiar. We apologize by reference to the Brussels customs.18

His stay in France no doubt improved Kafka’s knowledge of French, which was based on his firm knowledge of Latin. French literature and written texts thus became a common topic in Kafka’s correspondence:

Please, Max, if you should see any French papers in Germany, buy them at my expense and bring them back for me.19

And one more request, it goes on forever but this is the last: I read here almost only in Czech and French, and nothing but autobiographies or correspondence, naturally in fairly good print.20

I most want to read books that are originally Czech or French, not translations.21

Like Latin and Greek, French was very much a foreign language for Kafka. It had no special place in Kafka’s life: his contact with French was restricted to his time at grammar school, to private lessons and to irregular vacations in France. Subsequent intensive reading strengthened his passive knowledge of standard French, just as his active knowledge was strengthened for some time by regular conversation with the governess mentioned above.

ITALIAN

Another of Kafka’s foreign languages was Italian, which he learned in the autumn of 1907, when he was working in the insurance company Assicurazioni Generali, which had its headquarters in Trieste:

I am learning Italian because I will probably go to Trieste first.22

His motivation for learning Italian diminished as soon as Kafka left the insurance company on 15 July 1908, although he was to use the basics of the language later, when travelling to Italian-speaking regions in 1909, 1911, 1913, and 1920. It is most probable that he took up Italian again even before those travels, although not much of his Italian had remained from the autumn of 1907:

Today I was in Malcesine where Goethe had the adventure you would know about if you had read the Italian Journey, which you ought to do soon. The castellan showed me the place where Goethe did his drawing; but this spot did not correspond with the journal and so we could not agree about that, any more than we could in Italian.23

Kafka’s self-irony concerning his ability to speak Italian was apparent even as he made travel arrangements:

Please look out for a place for summer or autumn where I could live in vegetarian style, stay healthy, where I could be alone without feeling forlorn, where even a blockhead can learn Italian etc.24

The use and knowledge of Italian seems to have slowly disappeared from Kafka’s life and private texts, but it remains a presence in his writings – at least in ‘The aeroplanes in Brescia’ or in the novel The Trial.25

ENGLISH & SPANISH

At various times Kafka also mentioned two other languages, English and Spanish:

[. . .] if my prospects don’t improve by October, I shall take the advanced course at the Business Academy and learn Spanish, in addition to my French and English. If you want to join me, it would be nice. I would make up for the edge you have over me at studying impatiently; my uncle would have to find a position for us in Spain, or else we could go to South America or to the Azores, to Madeira.26

In regard to English Kafka confessed on the form from Assicurazioni Generali that he ‘lacks practice’.27 He seems not to have used the English that he probably also picked up during his studies at the Business Academy, where he was improving his practical qualifications before starting his career, to obtain information about America for his ‘American novel’.28 For this he used Czech, among other resources. Kafka’s plan to learn Spanish, which arose from his insecurity about earning a living at the very beginning of his career, evidently came to nothing after he got the job at Assicurazioni Generali. However, evidence of some residual knowledge of Spanish emerged later in connection with Alfred Löwy, an uncle on his mother’s side, and in ‘Memoirs of the Kalda railway’.29

HEBREW

By contrast, Kafka’s encounter with the basics of biblical Hebrew was closely connected to his education at grammar school, where he was introduced to Hebrew in his religious classes. Apart from the study of translations, an annual report from the grammar school mentions reading the Bible in the ‘original’ and describes the study of the original text in detail, mentioning the books of the Prophets, the 2nd, 3rd and 5th books of Moses (Exodus, Leviticus, Deuteronomy) and the Psalms.30 Hebrew naturally had a specific symbolic value for Kafka and his family, but outside the synagogue, Kafka had contact with Hebrew only at grammar school. In this period, as later, he learned Hebrew through German.

David Suchoff has set Kafka’s interest in Jewish languages in a broader literary context.31 Here I concentrate on Kafka’s acquisition of the language itself. Kafka began to take more of an interest in studying Hebrew again after 1917, when Modern Hebrew was recognized together with English as an administrative language of the Jewish regions in the British protectorate of Palestine. Biblical Hebrew was not the only variety that Kafka set himself to master. Although Friedrich Thieberger, the oldest son of a rabbi in Prague, who gave Kafka lessons starting in autumn of 1918, based them – in his own words – on biblical Hebrew, Kafka also began learning Hebrew from the German textbook of the Hebrew language by Moses Rath,32 which – at least according to Max Brod – contained material on some ‘everyday’ situations such as cooking and school. In addition to German and Hebrew textbooks and Hebrew grammar books, Kafka’s library contained a second edition of Rath’s textbook of 1917.33 Contradicting Brod’s testimony, Bodenheimer argues that the textbook did not contain Modem Hebrew,34 and indeed, with its method of using modified Bible texts, Rath’s textbook is far from taking a communicative approach. All the same, Kafka studied Hebrew mainly because he wanted to be able to communicate in it. In that sense, Brod’s testimony is correct.

In 1917, Kafka immersed himself in Hebrew to a greater extent than he admitted to his friends. In a diary entry of 10 September 1917, Brod notes that Kafka confided that he had been learning Hebrew. He had covered 45 lessons and hadn’t said a word to Brod about it when he surreptitiously tested Brod’s knowledge by asking about numbers and pronunciation.35 At this time Kafka tried to use Hebrew intensively, for example in an excuse for an rare failure to do homework.36 Despite his self-deprecating remarks he learned enough Hebrew to communicate in it during his stay in Meran.

One of the guests, for example, was a Turkish-Jewish rug dealer, with whom I exchanged my scanty words of Hebrew [. . .]37

Reading Hebrew texts such as newspapers printed in Hebrew letters or Kabbalah became a regular activity.38

Kafka studied Hebrew not only with Thieberger, but also with Max Brod and Jiří Mordechai Langer and then with Irma (Miriam) Singer and Felix Weltsch in the following years. In a letter in German to his fiancée Julie Wohryzek, he wrote a greeting phrase in Hebrew letters:  (pleasantly peace).39 According to Brod’s memoirs, Kafka studied Hebrew together with him and Jiří Langer and was ahead of Brod, as is clear from Kafka’s letters of 1918:

(pleasantly peace).39 According to Brod’s memoirs, Kafka studied Hebrew together with him and Jiří Langer and was ahead of Brod, as is clear from Kafka’s letters of 1918:

Dear Max, Thank you for the letter and your caution. Your Hebrew is not bad; there are a few mistakes at the beginning, but once you get in, you make no errors. I learn nothing, seek only to hold on to what I know nor would I have it otherwise. I spend the whole day in the garden.40

Once I am in Schelesen I may send you a list of questions on Hebrew matters. It will not mean much work for you, the questions are such as can be answered with a word or shake of the head and we will have a correspondence in Hebrew.41

According to Miriam Singer, Kafka took private lessons in Hebrew with her and Felix Weltsch.42 A retrospective claim by Langer that Kafka was able to communicate with him in Hebrew fluently43 does not, however, seem credible in view of the circumstances: it is not likely that tram passengers would understand and look on with admiration as two people spoke about so complex a topic as aviation in Hebrew. In view of the revived antisemitism in Prague after World War I, it is improbable that the two would have used Hebrew openly. In private, Kafka played with Hebrew even in Czech, as is apparent from a Czech note to Ottla and Josef David:

I’m looking forward to Věra [= at this time 10 weeks old], she is surely very talented, after all she already speaks Hebrew, as you write. Haam then is Hebrew and means ‘the people’. However, she doesn’t pronounce the word quite correctly; it should be ‘haám’ not ‘háam’.44 Please correct her; if she gets habituated to this mistake in her youth it might stick.45

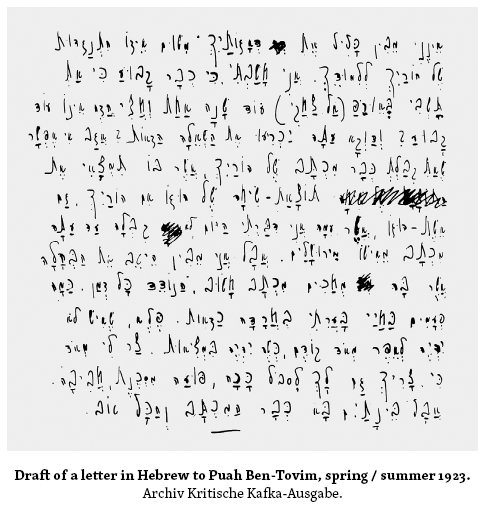

Kafka’s Hebrew notes – Bodenheimer mentions hundreds of pages – contain mostly common words.46 Although Kafka stopped taking Hebrew lessons in 1922 for health and personal reasons, he started again in 1923 and learned Modern Hebrew from Puah Ben-Tovim, as mentioned in the previous chapter. At that time Kafka was receiving Hebrew letters and himself wrote in Hebrew to Puah Ben-Tovim in the spring and summer of 1923.47 An English excerpt from the draft of one of his Hebrew letters demonstrates that Kafka’s knowledge of the language was sufficient for more than just trivial conversation:

I don’t understand your troubles with your parents’ disapproval of your study. I took it for granted that you would stay a year and half in Europe (don’t laugh), isn’t that certain yet? Are they settling the matter right now? By the way, it’s impossible that you’ve already received from your parents the letter with the results of Hugo’s discussion with them. His wife, who I talked to today, has also not yet received a letter from her husband, who is in Jerusalem. But I well understand the chaos one often feels when waiting for a decisive letter that is lost somewhere. I have felt the same anxiety many times in my life. It’s a wonder that nobody turns to ash earlier than they actually do. I’m sorry that you are suffering so much, poor, dear Puah, meanwhile the letter has come and everything is all right now.

In May/June 1923 Kafka checked a Hebrew text and translated Hebrew business texts for Oskar Baum.48 Kafka did not quit learning Hebrew in July 1923 even in Müritz, where he was confronted with ‘lots of Hebrew-speaking, healthy, happy children’.49 He read Hebrew together with Dora Diamant, whom he met there,50 and received Hebrew letters from young participants in a camp organized by a Jewish youth centre in Berlin:

Please give my regards to all my friends at the Home, especially to Bine, to whom I would have written long time ago if I did not cherish the ambition to thank her for her fine Hebrew with Hebrew on my part, although not so fine. In my present state of restlessness, I have not found the composure to make such an effort in Hebrew.51

Hebrew also had its place at the ‘Institute for Jewish Studies’ that Kafka attended after moving to Berlin in 1923; this was his main point of contact with the outside world.

Hebrew even played a role in Kafka’s reading: ‘Otherwise I have been reading little, and only in Hebrew.’52 He was probably referring to Josef Chajim Brenner’s Hebrew novel Infertility and Failure.53 Kafka mentioned this title, in Hebrew, in a letter to Robert Klopstock and attempted to analyze the meaning of the two title words:

are two words, nouns which I also don’t understand completely, but which in any case seem to try to convey the notion of misfortune.

are two words, nouns which I also don’t understand completely, but which in any case seem to try to convey the notion of misfortune.  literally means childlessness, maybe fruitlessness, unfruitfulness, senseless effort as well and

literally means childlessness, maybe fruitlessness, unfruitfulness, senseless effort as well and  literally means: to stumble, to fall.54

literally means: to stumble, to fall.54

Here he also mentioned the pace of his own reading: ‘Now I’ve been here for a month and I have read thirty-two pages.’55 The slow pace was a result of the fact that Kafka was not enthused by Brenner’s novel and had some problems understanding it.

Moreover, it seems possible that Hebrew was relevant in Kafka’s home and private life in this time. Based on everything that is known about Kafka and Dora Diamant, he read in Hebrew from the beginning of their relationship. Diamant mentioned that Kafka had planned to go to Palestine with her, and she repeatedly refers to her inadequate competence in German in her letters to Brod and Klopstock.56 Diamant, daughter of an ultraconservative East European Chassidic family, could speak and read both Hebrew and Yiddish without difficulty, and so she may also have done so with Kafka.57 Kafka himself, however, was quite self-deprecating about his own Hebrew:

I realized that if I wanted to go on living somehow I would have to do something altogether radical and wanted to go to Palestine. I certainly would not have been up to it, I am also fairly unprepared in Hebrew and in other aspects; but I had to give myself something to hope for.58

Kafka even saw Berlin as a ‘transit station’ on the way to Palestine.59 There is no doubt that Kafka connected Hebrew with health, freedom and life, and that ‘he yearned for’ Palestine.60 His daily contact with Hebrew embodied and fulfilled this desire. This is evident from his insertion of Hebrew phrases into his German when he lived with Dora Diamant:

Those few days I lived on you (I would almost say, based maybe on a Hebrew idiom: on your fat); the paper I am writing on comes from you, the pen comes from you, etc.61

Hebrew – unlike the classical languages he learned at grammar school or the foreign languages he studied at the beginning of his career (French, English, or Italian) – acquired a special position in his life. Kafka learned Hebrew more or less on his own or under professional guidance for several years; he could read and partially write it; he was able to communicate in Hebrew, and it is possible that, at least to some extent, he associated Hebrew with his private domain, which may explain the linguistic interference in German mentioned above. Nevertheless, Bodenheimer has reservations about his faculties in Hebrew, claiming that Kafka ‘had steady contact with religious Hebrew expressions and writings’ and ‘that he was quite eager to grasp classical figures of speech, but he lacked any knowledge of the sources of references to the Bible and the prayer book. Hebrew was a foreign language to him in every sense of the word.’62

YIDDISH

Kafka’s ‘Jewish revival’ in 1911–12, was related not to Hebrew but to Yiddish, or rather to performances given in Prague by an East European theater company, starting on 5 October 1911.63 On 18 February 1912, Kafka organized a poetry evening for Yitzchak Löwy. Kafka also introduced him in a speech now known under the title ‘Introductory speech on Jargon’. The speech concerned Eastern Yiddish, which Kafka was enthusiastic about but did not always understand fully. In his diary, for example, he translated the Eastern Jewish word Belfer as ‘Hilfslehrer’ (assistant teacher) or Schmatten as ‘Hadern’ (rags) in brackets.64 Elsewhere, his literal translation of the phrase ‘toire is[. . .] die beste schoire [shoire]’ as ‘Thora ist die beste Ware’65 or ‘Torah is the best commodity’ might be interpreted as ironic, but could be the result of unfamiliarity with the phrasematic meaning ‘knowledge is the best kind of investment’. Certainly it is no coincidence that Kafka only quoted single words in Yiddish, whereas he was able to reproduce whole Czech sentences that he had heard without mistakes in grammar and orthography, and could therefore write letters in Czech. This may be considered an indication that Kafka’s familiarity with Yiddish was passive and limited.

Given that Kafka was ‘the Westernmost of Western Jews’, as he characterized himself in a letter to Milena, not only Eastern Yiddish but also Western Yiddish, which Kafka’s grandparents may still have spoken in their youth, should also be taken into account. During the 19th century Western Yiddish disappeared from the Bohemian lands as a result of Jewish emancipation and assimilation. A halfway stage of this process was the Jewish-German ethnolect also called ‘Mauscheldeutsch’ or ‘Schwundstufen-Jiddisch’,66 used by the generation of speakers who were born in the ghetto or its remnant and aimed to establish themselves in a society dominated by German. This ethnically-marked version of German was lampooned, for example, by Štěpánek’s plays from the first half of the 19th century, and by Kafka himself in a description of mauscheln discussed in the next chapter.

The parodies of Štěpánek highlight the low prestige of this variety, and of Yiddish in general, in the Bohemian lands; this was why the ethnolect vanished during the second half of the 19th century, just as Western Yiddish itself had disappeared as a result of self-regulatory efforts by Jewish speakers in favour of the German ‘standard’, or more accurately in favour of the variety of German that the speakers in Bohemia viewed as standard. It was because of the common sources of Yiddish and German that traces of Yiddish could survive in the German of those speakers into the second half of the 19th century. Yiddish was originally based on a Southern variety of German,67 and this complicated the identification of substrate interferences e.g. in pronunciation or syntax for speakers who had shifted from Yiddish to German. It also complicates the identification of Yiddish semantic substrate for us,68 but we see Yiddish fragments still appearing in Kafka’s parents’ letters, or perhaps more accurately, we can see that the language of these texts might be interpreted as influenced by Yiddish or variants of South German dialects. In the very same cases Czech might also be regarded as an influence, and so we could be dealing with multiple models for the contact replicas.

One possible echo of Western Yiddish in Hermann Kafka’s German is the form mechst (instead of möchtest), which – in the sentence u[nd] Du erst Donerstag mein Brief erhalten mechst – functions as an auxiliary verb referring to the future, and thus performs a function similar to the Eastern Yiddish veln (‘wollen’ with the meaning ‘will’ instead of ‘want’).69 This hypothesis would have to be tested against other examples of the German used by the Prague Jewish community, especially since there is no support for it in the standard literature such as Lockwood.70 The example ich habe [?gegen?] meiner Princip geschrieben could represent a sediment of the Yiddish substrate forms mayner, mayne, mains instead of mein, meine, mein;71 the preposition gegen is combined in Bavarian German with the dative. Other phenomena that might be reminiscent of Yiddish include the following: the regular infinitive schmeichelen and versicheren instead of schmeicheln and versichern,72 lack of discrimination between the dative and accusative of the article, word order of pronouns in the dative-accusative instead of the accusative-dative in und werde Dir es instead of ‘und werde es Dir’,73 absence of frame construction in Daß wird werden ein freudiges Wiedersehen instead of ‘Das wird ein freudiges Wiedersehen werden’,74 relative was like in zwei Tage, was ich von Dir Abschied genommen habe,75 etc. The problem is – for the speaker as well as for us – that these phenomena also have parallels in the non-native German of Czechs, as well as in spoken German and South German dialects. A good example is the delabialization mechst instead of möchtest (Hermann Kafka sometimes used the ‘correct’ form as well), which could be explained with reference to Yiddish or Czech non-native varieties of German, as well as with reference to the South German dialects or language spoken in the South.

Similar phenomena can be identified in the language of Kafka’s mother, Julie Kafka, née Löwy. Blahak points out that her father was a Jewish hop merchant and this group was said to have used Yiddish as its working language until the 20th century.76 Other non-lexical phenomena, which appear sporadically, like the absence of -n in the dative plural in Von meinen lieben Eltern und Geschwister[n] and von Vater und Kinder[n],77 the imperatives gebe instead of gib or vergesse instead of vergiss,78 and word order forms such as Die frühere Adresse habe ich vom Onkel angegeben etc.,79 are hardly strong proof of a Yiddish substrate because they are also present in non-standard German varieties. The Yiddish vocabulary, like Mischpoche or Mišpoche (mischpóche) etc.,80 is very restricted in Julie Kafka’s German texts, as is usual in a substrate situation as well as in a situation of language shift, but it is nonetheless present, suggesting that the Yiddish heritage had been transferred from the grandparents’ generation to the parents’ generation in this case.

Some non-lexical phenomena in Kafka’s German could also relate to a Yiddish substrate: the pronunciation Vorworf,81 or perhaps frägen,82 the apocope in Brück, Diel, Tasch,83 plural 8 Tag, die Haar[e], or Körpers,84 as well as lack of distinction made between dative and accusative of pronouns and articles, the gender and case indifference of the indefinite article, or the plural of de-adjectival substantives without -n,85 features also present in Bavarian German. Another marked feature is the high frequency of diminutives (Yiddish, like Czech and other Slavonic languages, even has two levels of diminutives),86 or – according to Krolop – the greater frequency of the construction vergessen auf etc.87 Blahak even thinks that the manuscripts of Kafka’s literary texts reflect the West Yiddish pronunciation in Bohemia, as in the cases of Zache corrected by Kafka to Sache and the hypercorrect suständig corrected to zuständig, or Vort corrected to Wort and fas corrected to was.88 Yet these pieces of evidence are hardly strong proof of a Yiddish substrate in Franz Kafka’s German because even these examples can be explained as writing errors, analogies (Dunkel der Fauteuils und Körpers) or dialectal South German phenomena (lack of sonority in lenis consonants). We must add that these phenomena are not consistent but appear – with the exception of Blahak’s examples concerning pronunciation of s/z and f/v – only in isolated instances, as in the case of the German of Franz Kafka’s mother.

On the other hand, these pieces of evidence – especially the apocopes in Brück, Diel, Tasch or the orthography of compositions like Dorf-Winterarbeit89 – have a higher frequency during the years 1911–1912, which was the time of Kafka’s ‘Jewish rebirth’. This could support the theory that Kafka – at least to some degree – consciously evoked Yiddish in his German texts during this time. He at least is conscious of these forms. Later he comments, for example, on Tile Rössler’s misspelling of Schale as Schaale by pointing to the Yiddish spelling of fraage instead of the German Frage:

It is charming the way you write Schaale with a double a, the way Frage is written in Yiddish, I think. Yes, the Schale (bowl) is also intended to be a Frage (question) addressed to you, the question: ‘Say, Tile, when will you get around to smashing me?’90

Kafka also noticed and commented on the possible translation of Yiddish phrases in Karl Kraus’ German, as presented in the next chapter, and in Max Brod’s German translation of Leoš Janáček’s Její pastorkyňa (Jenůfa), in which Brod tried to find equivalents to convey the special flavour of an opera originally written in Czech dialect. In a letter to Brod written on 6 October 1917, Kafka quoted some phrases and sentences from the translation that seemed to him similar to the German ‘that we have learned from the lips of our un-German mothers’.91 He also hears these (Yiddish) ‘sounds from the ground’ in the German speech of his father, as in ich zerreisse dich wie einen Fisch,92 as well as in the Yiddish substrate patterns in Prague German:

I don’t know whether ‘nur’ is ‘jen’ here, you see this ‘nur’ is a Prague-Jewish nur, signifying a request, like ‘ihr könnt es ruhig machen’ (go ahead and do it).93

As usual in a substrate situation combined with a language shift, the Yiddish loanwords in German are very rare, but nevertheless they are present in Kafka’s private texts as well, for example in references to Kafka’s father calling Max Brod meschuggener ritoch.94 Kafka also used the term Moule,95 that is Moule/moul/moül, which is a widespread form of the Hebrew Mohel (circumciser) in Western Yiddish.96

This evidence still does not support any claim that Kafka was an active speaker of Western or Eastern Yiddish. Circumstances suggest otherwise. It is more likely a matter of the Yiddish substrate in the German spoken by assimilated German Jews, a substrate that also survived because Yiddish and German share some common origins, so that Yiddish or bilingual Yiddish and German speakers of the grandparents’ generation who preferred or were shifting to German could not control the Yiddish substrate in their German. The next generation, learning the German of its parents, could not identify these specific forms as distinctive at least before going through school, if at all. Hermann Kafka’s school career was, of course, very short, while as regards his wife, female schooling did not extend to the secondary level until the second half of the 19th century.

Kafka also used some semantic loans from Western Yiddish unconsciously. The term Winkel in the meaning ‘Ecke’ (corner) in the sentence Ich habe kaum etwas mit mir gemeinsam und sollte mich ganz still, zufrieden damit daß ich atmen kann in einen Winkel stellen,97 used by Kafka, is precisely this kind of substrate interference from Westem Yiddish. Kafka’s exclusive use of the term Junge (boy) instead of the usual South German Bub, common in Prague, can be explained either by the North Bohemian Junge or by the lexeme Junge/jingel that is common in Western Yiddish.98

In describing Yitzchak Löwy, Kafka characterized the situation of bilingual speakers of two closely related languages living in Bohemia at the start of the emancipation process: ‘Their language fluctuates between Yiddish and German, inclining more to German’.99 In Kafka’s case, because he himself belonged to the second generation without Yiddish, or without German and Yiddish bilingualism, we cannot talk of individual interferences, but rather of collectively used forms that can be understood as substrate traces of Western Yiddish in German spoken by Bohemian (and Moravian) Jews. Kafka acquired them as a part of German in his social context, a context that he is aware of, and can manage, although some substrate pattern replications and semantic loans from Jargon to German were out of his control. In reaction to two opposing reviews, one seeing ‘Metamorphosis’ as ‘ur-German’ and the other considering it ‘the most Jewish document of our time’, Kafka asked himself if he was ‘a circus rider on 2 horses’, in danger of falling.100 In regard to German his seat on the horse was firm.

GERMAN & CZECH

It is clear that standard German was not the first variety of German that Kafka acquired and used. It was at school that Kafka went on to learn standard German – not so firmly stabilized or fully established at this time – as was and is usual. German, as well as Czech, was the language Kafka acquired in primary socialization at his parents’ home as a first language. Acquired through the Czech staff in the household of his father and mother, Franz Kafka’s knowledge of Czech in addition to German could be characterized as early bilingualism, and it was probably at this time that the foundations of his later ability to switch between German and Czech were laid. This ability was developed in secondary socialization at school and later in his private and professional life. Yet there is a clear difference between the status, use and knowledge of the two languages for Kafka.

The difference was not so distinct in his pre-school years, when Kafka was surrounded by domestic staff who spoke Czech. Hermann Kafka’s household employed Czech staff, as I showed in the previous chapter, for various reasons including the fact that knowledge of both German and Czech was a prerequisite for the success of the future heir of a Prague dealer in fancy and dry goods. It was also a question of economy; Czech staff were not as expensive as German. Whatever the balance of reasons, Czechs were at this early time an integral part of Kafka’s everyday life and one might even speculate that Kafka’s ‘stammering’ when speaking to his father resulted from the cognitive pressure that can be part of bilingualism when a speaker acquires two languages without identifying them with distinct speakers:

What I got from you [. . .] was a hesitant, stammering mode of speech, and even that was still too much for you, and finally I kept silent, at first perhaps out of defiance and then because I could neither think nor speak in your presence.101

I remember going for a walk one evening with you and Mother, it was on Josephsplatz near where the Länderbank is today, and I began talking about these interesting things, in a stupidly boastful, superior, proud, detached (that was lying), cold (that was genuine), and stammering manner; as indeed I usually talked to you, reproaching the two of you for the fact that I had been left uninstructed, that I had been close to great dangers [. . .]; but finally I hinted that now [. . .] everything was all right.102

There may well have been other reasons for this problem, such as sheer fear of his father, but it cannot be ruled out that Kafka had difficulties separating Czech and German because the languages were not connected distinctively with different speakers or speaker groups: German with parents and Czech with the staff. His parents were bilingual in the spoken language and could switch between the two languages especially when talking to domestic staff, many of whom could not understand or speak German effectively, as well as when talking on domestic topics. We can thus assume that there were situations in which code-switching took place in the presence of little Franz, the first child in the family. This would not necessarily imply that Kafka acquired Czech first and better than German through the domestic staff responsible for him. His mother, of course, was present at home not just during her confinements for the births of her sons Georg and Heinrich, although she helped her husband in the store and with accounts.

That there was language switching in the immediate family is also suggested by evidence that Czech played a certain role in the language of Julie Kafka and the way that she addressed her children. According to Kafka’s letter to Felice Bauer of 3 November 1912, she had ‘constantly addressed [Felix] ‘good boy’ or ‘little boy’ in Czech’.103 Julie’s use of Czech in this way was probably not limited to her grandson Felix, the son of the predominantly German-speaking couple Valerie and Karl Hermann. Even after her daughters had grown up, she addressed them in German letters using the diminutive forms of Czech vocatives Ottilko, Ellinko etc. as mentioned in the previous chapter. Czech was thus the language of emotion, and the play with code switching and hybridity of speech was probably a part of everyday culture in the family, including songs like ‘Wir sind die tapferen Idioten / mit den zerrissenen Kalhoten . . .’,104 where the Czech word kalhoty (pants) is inserted in the German texts and acquires a German ending.

Yet it is also clear in this hybrid word and song that German was the first language for all the Kafkas, not only the parents. Julie Kafka’s words about herself and her husband shed light on this:

I, as father is too, am fond of him [= Josef David, Ottla’s future Czech husband]. If only he were willing to speak a little bit of German; but he doesn’t speak a single word and although we speak Bohemian quite well, it is nevertheless a strain to be forced to speak Czech for a whole evening. Perhaps you could point this out to him.105

Code-switching can be assumed to have taken place among staff as well, for at least a rudimentary knowledge of German was a prerequisite for employment in middle-class, German-speaking families. Little Franz may therefore have had problems with the fact that Czech and German were not strictly connected with particular speakers and situations – staff or parents – in Hermann Kafka’s household. This may have been exacerbated by the fact that Franz had no natural partner for conversation until 1889, when his sister Elli was born (his brothers Georg and Heinrich died before they were able to speak) and Franz was beginning elementary school. It certainly took a while before Elli started speaking, but after her birth and the births of other sisters (Valli in 1890 and Ottla in 1892), German became the primary language of Franz’s conversation in Hermann Kafka’s household in terms of relative time spent speaking in it as well as its status. It was the dominant language of the ‘nuclear’ family when staff were not present, even though the Czechs Františka Nedvědová, Marie Zemanová (nanny) and Anna Čuchalová (wet nurse) were working in the household at that time (around 1890). The family could afford a German baby-sitter, Elvira Sterk, only in later years (the growing prosperity of the family was also reflected in the move to a new apartment). Elvira worked there until 1902 and was succeeded by the Czech Anna Pouzarová.106

With such a background, it is no wonder that little Franz (or his parents) listed both German and Czech in answer to the question about his ‘common language’ when he enrolled in the 1st grade of the German public school in 1889. German was not only the language of instruction there; from the 1st to 4th grade, students also studied the German language in classes on reading, handwriting, spelling, and writing style. Czech classes started in the 3rd grade with fewer hours. During grammar school, the asymmetry in the status of German and Czech in Bohemia and in Kafka’s school daily life became more marked. In comparison with German (the language of instruction) Czech was only an optional subject at German grammar schools, with less homework and fewer hours of instruction. It was here, in the 3rd and 4th grade of primary school and during eight years of grammar school (with the exception of one half-year of stenography instead of Czech), that Kafka significantly enlarged his vocabulary, acquired the written form of the Czech language, and learned how to spell in Czech correctly (with only minor mistakes in diacritics). In the chapter on Franz Kafka at school I will sketch Kafka’s education in Czech and in Czech literature in more detail.

The often mentioned declaration of Czech alongside German in school records for Kafka’s first two years of primary school refers, incidentally, not to Kafka’s ‘mother tongue’ but to his ‘common language’, a category referring to knowledge of language for ordinary communication and not identical with the category of nationality. Indeed, although little Franz may well have picked up on discussions about the national implications of such information at home, e.g. in connection with the impending 1890 census, we can hardly consider the information given by a six- or seven-year old boy to be an avowal of an internalized linguistic, national identity. Furthermore, the school lists are a record of structured interviews with the children’s parents or guardians, which means that the data about ‘common’ language may be of limited value given the sensitive nature of the language issues and the formality of the interview situation.107 Nevertheless, despite the fact that a national interpretation of this data was inadmissible according to Austrian legislation and legal practice at the time, this inference continues to be made. Incidentally, in records from Kafka’s fourth school year onwards, we simply find his language defined as ‘German’.108 It was also the language of instruction at school and university and of Kafka’s legal jobs as well as the language of his literary activities. This is in no way at odds with the fact that Kafka voluntarily took Czech lessons at the German grammar school for years in order to learn to write in Czech in expectation of the future importance of Czech in the business of his father or as a lawyer in a state institution or a corporate company in socially bilingual Bohemia.

CZECH

The mode of acquisition of Czech in the Kafka family has been described above. As regards his tutored acquisition of Czech I shall say more in the chapter on Franz Kafka at school. The Czech classes were also important for Kafka’s reading competence in Czech, as discussed in the chapter on Franz Kafka’s Czech reading. In the present section I would like simply to give a brief sketch of situations in which he used Czech and to present the characteristic features of Czech texts authentically drafted by Franz Kafka.

During his studies at the German University in Prague, Kafka encountered Czech only in informal situations. It is no wonder that – despite continued contact with his Czech teacher from grammar school109 – Kafka lost the knack of actively using the ‘classic’ forms.110 On 30 June 1908, he applied for a position in the Workers’ Accident Insurance Company for the Kingdom of Bohemia using a dual-language German and Czech application form. In this application he mentioned his knowledge of German and Czech in spoken and written form and signed the German version as Franz Kafka and the Czech version as František Kafka.111 Before 1918, however, he only occasionally used German and Czech in bilingual correspondence with the board of the insurance company, but could use Czech in conversation with some employees in the company, with officials in the state and municipal administration as well as with civil servants.

His lack of practice in written Czech became evident after 1918, as Czech became the main official language and the preferred language on the board of the insurance company.112 Kafka switched to Czech in correspondence addressed to the board on 12 January 1919 and more than twenty official Czech letters apparently from Kafka to the board of the company have survived. But only two of them – written on 4 May 1920 in Meran and on 16 March 1921 in Matliary – are definitely authentic in the sense of his own unaided draft, while another three – written on 1 March 1919, 14 November 1919, and 6 May 1921 – may possibly have been drafted by Kafka himself. The others are translations or were checked by Josef David, Kafka’s Czech brother-in-law, or by Kafka’s sister Ottla, specifically the letters written to the insurance company on 27 January 1921, 18 August 1921, 20 December 1923, or 8 January 1924.113 The shift to Czech is also evident in the form of address on envelopes of letters sent to the family in Prague.

Czech was nonetheless a part of Kafka’s everyday life both before and after 1918, although with a greater intensity after 1918. Thus, Kafka spoke Czech to the domestic staff and to employees in the household and store of his parents, as described above. Kafka also communicated in Czech with workers in his family’s asbestos factory in Prague Žižkov as well as with his landlords (Michls, Hniličkas) and staff at the Schönborn Palace in Prague or Zürau/Siřem. In a letter to Milena written around 5 May 1920, Kafka quoted a maid from the Schönborn Palace who had commented on his spitting blood: ‘Pane doktore, s Vámi to dlouho nepotrvá.’ (You won’t be around for long, Mr Kafka.)114 After 1918 these Czech allusions multiplied. To a certain extent this also applied to his circle of friends. He communicated in Czech not only with Milena Jesenská, but in certain situations with his friend Max Brod (outside of Bohemia),115 the Czech dramatist František Langer, Czech poet Fráňa Šrámek and translator Rudolf Fuchs. I document these literary and/or culturally relevant contacts in the chapter on Kafka’s Czech reading.

Kafka also used Czech in conversation with employees and patients in sanatoria in Bohemia and Slovakia. In his leisure activities (swimming, rowing, gardening), and in fact whenever he was out and about in Prague (on the streets, in restaurants, at the Selbstwehr editorial office), Kafka was not only confronted with Czech, but could respond in Czech without difficulty, as well as remember and write down Czech words and whole sentences without a single mistake.116 This is worth noting given the contrast with Kafka’s use of Yiddish, which he heard from the group of East European actors and from Löwy, and which was limited to isolated words at most.

Nevertheless, Kafka’s written Czech shows the influence of German. The fact that Kafka wrote only a limited number of Czech texts as well as the range and character of domains within which Kafka functioned in German or Czech, and last but not least his choice of German as literary language, reveal that Kafka’s bilingualism was functional, but with respect to written Czech not completely structural.

The form of his Czech can be demonstrated using all these written texts. Some were authentically drafted by Kafka: two or five official texts to the insurance company, six short texts to Josef David (4th week of January 1921; 4 March 1921; June 1921; 22–23 August 1921; 3 October 1923; mid-December 1923) and some text fragments in letters to Ottla, further quotations in diaries and letters to Max Brod and Milena Jesenská as well as one text to Marie Wernerová (16–19 January 1924) and another to Růžena Hejná (1 October 1917), a draft for Olga Stüdl (Franz Kafka to Otlla, end of March 1919) and the draft of a tax declaration for 1920.117

It is not a large corpus but it enables us to say a great deal. The diacritical orthography and typeface of Kafka’s texts were essentially correct but Kafka seems to have had a problem with vocal quantity. He used not only vúbec instead of vůbec, but also short vowels for long – especially at the end of words, such as nepotřebuji (3.ps.pl.), dělaji (3.ps.pl.), hezky (adj.) or (oprav) ji (to), which is possible in non-Standard Czech pronunciation, particularly in Prague. He also used a hypercorrect lengthening in děkují instead of děkuji (1.ps.sg.), as well as a lengthening in totíž instead of totiž, cený instead of ceny, and possibly also hebrejský instead of hebrejsky (adverb). Further, he used long instead of short vowels in the first syllable, stressed in Czech, such as náděje, Jíříček, dívadlo, s ními, láhvička, nábidka etc. The last feature is a clear interference from German where all long vowels are stressed, and the lengthening of the first stressed syllable gives the impression that he was a speaker of Czech with a German accent. The influence of German is also present in the German-like spellings Horáz instead of Horác, kommunisté instead of komunisté, o Berlinském eventu instead of o berlínském eventu etc.

His declension of nouns and adjectives is on the whole correct, including correct inflection of words with genus that are different in Czech and German: horečka (f.) vs. ‘Fieber’ (n.), na přátelské noze (f.) vs. ‘Fuß’ (m.) / ‘Bein’ (n.), čas (m.) vs. ‘Zeit’ (f.), as well as use of allomorphs and suppletive forms: na přátelské noze (loc. sg.) vs. ‘noha’ (nom. sg.), na druhé stránce (loc. sg.) vs. ‘stránka’ (nom. sg.), dobrý – lepší (good – better). There are only a few special features in Kafka’s declension of Czech. He used progressive, more colloquial substantive forms: vojáků, vůdců, papírů, řádků, vkladů, závodů, dnů (gen. pl.) instead of ‘vojákův, vůdcův, papírův, řádkův, vkladův, závodův, dnův’ (standard at this time). He also employed non-standard substantive, pronominal and verbal forms: slinama, s těma kalhotama instead of ‘slinami, s těmi kalhotami’ (instrumental fem.), celé noce instead of ‘celé noci’ or nehet pravého malíčka instead of ‘nehet pravého malíčku’, nepotřebuji, dělaji instead of ‘nepotřebují, dělají’, zatrh jsem si instead of ‘zatrhl jsem si’, and agrammatism (non-declension) of some proper names and toponyms: čtu v ‘Selbstwehr’ instead of ‘čtu v ‘Selbstwehru”, mohl koupit ‘Kid’ instead of ‘mohl koupit ‘Kida” and u Waldek & Wagner instead of ‘u Waldeka & Wagnera’, je tu Tatra instead of ‘jsou tu Tatry’. Similarly, we find female and other special forms of names given without marking as e.g. female through derivation: Hálka instead of ‘Hálková’, Bugsch instead of ‘Bugschová’ and rodina Gross instead of rodina ‘Grossova’ or ‘Grossovi’. In the address of letters to Ottla he used the simple ‘German’ form Kafka,118 whereas in the address of letters to Ottla David he used the derived form Davidová, but preferred the form David.119 The use of non-standard forms shows that his Czech was based primarily on conversation, and the last listed feature reveals the indirect influence of standard German usage as acquired in the formal acquisition of language.

Concerning the verbal aspect, Kafka sometimes had problems with it, as demonstrated in the first chapter. He used most verbs correctly, but his grasp of aspect could be shaky: buď bude třeba abych se dále léčil totiž bude náděje že bych se mohl ještě dále vyléčit instead of ‘buď bude třeba abych se dále léčil totiž bude náděje že bych se mohl vyléčit’, že bych snad z Vašeho dvora mléko pravidélně dostati mohla instead of ‘že bych snad z Vašeho dvora mléko pravidelně mohla dostávati mohla’, Písemně Vám ale děkovat nemůže instead of ‘Písemně Vám ale poděkovat nemůže’ and ‘Na Křivanu jsem se dal vyfotografovat jak to na druhé stránce vidíš’ rather than Na Křivanu jsem se dal fotografovat jak to na druhé stránce vidíš, or ‘znáte tu uzávěrku, že? Ta se vždy časem rozpadne’ rather than znáte tu uzávěrku, že? Ta se vždy časem rozpadá.

This specific use has more to do with aspect semantics in specific contexts and situations than with purely formal inflection but still indicates that his grasp of Czech aspect – effectively acquired by native speakers in pre-school years and fixed later – was “influenced” indirectly by German as a dominant language that makes more elaborate differentiations in school language teaching of grammar than Czech does. A similar case is the hypercorrect use of adjective mluví [. . .] hebrejský (she speaks Hebrew) instead of the adverb ‘mluví [. . .] hebrejsky’. This suggests Kafka’s uncertainty about the differentiation and may be explained by the fact that German does not differentiate between adverbs in adverbial phrases and adjectives in the predicative (both in the context of verbal phrase), whereas Czech does.

On the syntactic level we can point out that Kafka’s Czech sentences are grammatically correct and mostly well formed including congruence in the sentence as well as in specific nominal phrases with numerals; Kafka correctly combines the numeral ‘five’ with the genitive numerative: pět slov (five words). Otherwise syntax provides the best examples of the dominance of German in Kafka’s use of language in his everyday life. In contrast to Czech with its ‘free’ word order governed by differentiation of topic and focus, Kafka tends in Czech to keep to the grammatically bound second position of finite verbs in a independent clause like neboť já zacházím už s tím ústavem, jako dítě s rodiči by se zacházeti neodvážilo instead of ‘neboť já už s tím ústavem zacházím, jako dítě s rodiči by se zacházeti neodvážilo’ (because I already treat my company in a way that no child would dare to treat its parents) etc. as well as to placing a finite verb last in a subordinate clause as in German: . . .že bych snad z Vašeho dvora mléko pravidelně dostati mohla instead of ‘. . .že bych snad z Vašeho dvora mohla pravidelně dostávat mléko’ (so that I might be able to obtain milk regularly from your farm), . . .u kterého Vaše slečna sestra byla zaměstnána instead of ‘. . .u kterého byla zaměstnána Vaše slečna sestra’ (with whom your sister was employed) etc.

We also find many phrases and sentences in his Czech texts based on and formed according to German models: correct Czech ‘mít strach z Berlína’ or ‘strašit Berlínem’ × Kafka’s dělat strach před Berlinem (instrumental) ↔ ‘Angst vor Berlin haben / machen’ (have / make fear for Berlin), ‘Hakoah prohrála se Slavií’ × Hakoah proti Slavii prohrála ↔ ‘Hakoah verlor gegen Slavia’ (Hakoah lost to Slavia), ‘(být) mimo domov (accusative)’ × (být) mimo domova (genitive) ↔ ‘außerhalb + genitive (sein)’ ((be) outside of), ‘psaní řediteli’ × psaní na ředitele (accusative) ↔ ‘Schreiben an den Direktor’ (letter to the director), although the Czech models already looked different at the beginning of the 20th century.

We now move on to vocabulary. In the chapter on Franz Kafka at school I point out that the school provided good conditions for the intensive acquisition of rich vocabulary. Comparison of Kafka’s use of lexical units with a dictionary of frequencies shows that more than 40% of the words that he used came from outside the set of 2000 basic words.120 Though he certainly had an excellent vocabulary, the codeswitching in To je tak jako Eulen nach Athen tragen (It is like carrying coals to Newcastle), těch dvacet korun předal jsem jednomu Kinderhortu (I gave those twenty crowns to a kindergarten) or referát o Berlinském eventu (report about the event in Berlin) reveals that it was not without gaps. There are also some semantic interferences, such as use of přijít instead of ‘přijet’, reflecting the situation in German which lacks the Czech differentiation between přijít / kommen (come) and přijet / kommen (come by car, train etc.) etc. While he used some phrasemes, like na druhé stránce (stránka) instead of ‘na druhé straně’ (strana; on the other hand) incorrectly, he was otherwise able to identify the phraseme na přátelské noze stojí used by his father as a germanism replicating a German phrase ‘auf freundschaftlichem Fuße stehen’ (to be on good terms).121

Last but not least, Kafka was able to use different Czech registers, as can be seen from the official style of his letters to the head of the insurance company and the informal style of his private letters. The informal style of the private letters also explains some of his colloquial forms. Furthermore, Kafka is obviously able to differentiate stylistically within a single text. In a letter to Josef David of January 1921 he changed the topic from a formal thanks for help to a description of an informal annoying situation in which he employed colloquial forms like točejí, křičejí instead of the standard ‘točí, křičí’ (they run around in circles shouting) to characterize the speech of the protagonists. Moreover in the same text he switched from standard to non-standard and back to standard as marked by the switch from formal infinitive form -ti to the informal form -t and later back again to -ti. The -t form is characteristic of spoken language in informal situations. This can be expected from him who subscribed to the Czech linguistic journal Naše řeč (Our Speech), oriented to language culture, from 1919–1922.122

But despite codeswitching and some semantic, syntactic and possibly also phonetic interference from German, his texts show very clearly that Kafka was fully in control of his communication in Czech. All the same, he tried to avoid using Czech, e.g., in his letters to Milena where he said: ‘don’t force me to write you Czech’.123 Elsewhere he reflects on his formal correspondence with the insurance company in a self-deprecating style. He describes himself as a ‘poor boy’ and his strategy as a ‘lie about my excellent Czech, a lie which I set in the world and which probably nobody believes’.124 The self-irony is followed by a request for translations of two other letters to help him maintain face. Yet for Kafka Czech was also the language of affection. In a letter to Milena at the beginning of their relationship he writes that Czech would have been ‘much more affectionate’ for him than German.125

GERMAN

In contrast to Czech, Kafka characterizes German as his ‘mother tongue’ and ‘natural’ for him even though he had not lived ‘among German people’.126 Commenting on his sister Ottla’s German, which supposedly contained ‘translations from Czech’ he elsewhere ironically called himself ‘half-German’.127 In the next chapter I shall explain the way in which this pragmatic, addressee-oriented self-deprecation can be understood as a bitter irony concerning the German of Jewish German-speakers. Of course, Kafka wrote to Max Brod about the German of their ‘un-German mothers’ as discussed above,128 but it is notable that although he was a self-aware language user and also very critical of his German in terms of the supposed norm, Kafka did not go as far in his diagnosis of the situation as Fritz Mauthner, for example. Mauthner refers to a ‘dead body of three languages’ within him and as a Jew feels the absence of a ‘true mother tongue’129. In fact the fin de siècle trends of stylization and literary skepsis with regard to language were a more important factor than the shape of language itself.

At the beginning of this chapter I argued against the notion of a ‘poor ghetto German’. Here I would like to summarize Kafka’s acquisition and use of German as well as comment on its locally specific shape. Franz Kafka acquired German naturally, untutored, in the later mainly German-speaking household of his parents, and continued and extended the acquisition of his first language at elementary and grammar school. German was not only the language of instruction there, but was the subject of special German classes. At elementary school Kafka had four years of special classes in reading, writing, grammar and spoken expression orientated primarily to pupils with German as mother tongue. He achieved As and Bs there. At grammar school German was also the language of instruction and the compulsory classes in German were more frequent and intensive than the optional classes in Czech. He had to write a class test in German every 8–10 days. His usual mark was B, but in some cases he was given an A or C. After grammar school he studied at Prague’s Charles University and then found employment in insurance companies, eventually finding a post at the Worker’s Accident Insurance Company for the Kingdom of Bohemia in Prague, which was dominated by German until 1918. In this position Kafka was responsible primarily for German-speaking territories and agenda. German also determined other domains of communication in his life. Even though he had friends and peers who were not German native speakers, most of these still spoke German, and, of course, as a literary writer, Kafka used only German.

Still, Kafka observed that his spoken idiom was recognizable as ‘Prager Deutsch’: ‘a landlady, the merry wife of the booksellers Taussig with very red and fat cheeks, recognizes my Prague German immediately’.130 Brod recalled that his friend checked and changed some expressions in his literary texts using Grimm’s dictionary to prepare them for publication in Leipzig, and supposed that this involved erasing ‘Prague-isms’ like paar instead of ‘ein paar’ as well as idiosyncrasies based on Czech syntax.131 This memory, however, suggests Kafka’s awareness of the difference between language norms in Leipzig and Prague, or in the ‘Reich’ and Austria, rather than his conviction in the poverty, insufficiency or deficiency of his language.

Krolop has analyzed Kafka’s German with respect to the comprehensibility of his literary texts for readers outside Austrian territory and has pointed out some lexical ‘austrianisms’, also used to some extent in South Germany, that might have caused difficulties for other German readers. These include Auslage for ‘Schaufenster’ (store window), dafürstehen for ‘sich lohnen’ (be worth it), Gasse for ‘Straße’ (street), Hausfrau for ‘Vermieterin’ (landlord), Haustor for ‘Haustür’ (front door), Kamin for ‘Schornstein’ (chimney), Kasten for ‘Schrank’ (dresser), laufen for ‘gehen’ (walk), Plafond for ‘(Zimmer-) Decke’ (ceiling), in erster Reihe for ‘in erster Linie’ (in the front row), Sessel for ‘Stuhl’ (chair), springen for ‘laufen’ (run), sperren for ‘schließen’ (close), Tasse for ‘Tablett’ (tray), Stiege for ‘Treppe’ (staircase), überwälzen for ‘abwälzen’ (unload), Verkühlung for ‘Erkältung’ (cold), Vorzimmer for ‘Diele’ (hallway) etc., that might potentially complicate the understanding of Kafka’s literary texts.132

The local shape of Kafka’s texts is also revealed in his non-literary texts. It affects the vocabulary of food and drink (Jause for ‘Frühstück’ (breakfast) as well as jausen, Nachtmahl for ‘Abendessen’ (dinner) as well as nachtmahlen, Vogerlsalat for ‘Feldsalat’ (salad), Schlagobers for ‘Sahne’ (cream) etc.), houses and buildings (Kaffeehaus for ‘Café’ (cafe), Haustor for ‘Haustür’ (front door), Kanzlei for ‘Büro’ (office), Vorzimmer for ‘Diele’ (hallway), Stiege for ‘Treppe’ (staircase), Durchhaus, Pawlatsche etc.), pieces of furniture (Kanapee and Fauteuil for ‘Sofa’ (coach), Kasten for ‘Schrank’ (dresser), Sessel for ‘Stuhl’ (chair), Kredenz for ‘Küchenschrank‘ (cupboard), Leintuch for ‘Betttuch’ or ‘Laken’ (sheet), Waschkasten for ‘Waschtisch’ (washstand) etc.), time expressions (Jänner for ‘Januar’ (January), Feber for ‘Februar’ (February), öfters for ‘öfter’ (more often) etc.), and personal names (Drecksorsch, Hausfrau for ‘Vermieterin’ (landlord), Junge vs. Bavarian Bub (lad), Germ./Bohemian Klempfner vs. Bavarian ‘Spengler’ (plumber), Zimmerherr for ‘Vermieter’ etc.) as well as vocabulary in other areas, such as Matura for ‘Abitur’ (final exam), Gendarm for ‘Polizist’ (policeman), together with Polizeimann, and Gendarmerie for ‘Polizeistation’ (police station).133 In the context of his work at the insurance company he used professional Austrian terminology, such as Ausfolgung for ‘Auszahlung’ (paying out), Beiziehung for ‘Heranziehung’ (attraction), Drucksorten for ‘Drucksachen’ (printed matter), Einreihung for ‘Einstufung’ (classification), Exekution for ‘Pfändung’ (seizure), Cassa for ‘Kasse’ (cash register), Petent for ‘Antragsteller’ (applicant), Rekurswerber, Urgenz for ‘Mahnung’ (reminder), Versicherungskataster (insurance register) etc.134

The lexical items also have a specific orthography matching the orthographical rules of Kafka’s time and space as well as pronunciation. A change in the orthography around 1902 is reflected – with a delay in Kafka’s texts, such as the shifts from Muth, nöthig, Theil, Thier. . . to Mut, nötig, Teil, Tier. . .; from Corridor, Rangclasse, Tuberculose, Publicum. . . to Korridor, Rangklasse, Tuberkulose, Publikum. . .; from Proceß (Kafka), Mediciner. . . to Prozeß, Mediziner. . . (Brod); from Litteratur (Kafka) to Literatur (Brod), or in doublets such as Theater/Teater, etc. The regional standard orthography is evident in gleichgiltig/gleichgültig, endgiltig/endgültig, villeicht/vielleicht, verleumden/verläumden etc. The (local) pronunciation is reflected in some instances of spelling of Tier for ‘Tür’ (Kafka also used Tür), Tringgeld for ‘Trinkgeld’, können for ‘gönnen’, kennen for ‘können’, Ausprache/Aussprache, Auschlag/Ausschlag, Austellung/Ausstellung, Hauschuhe/Hausschuhe, Winterock/Winterrock, Vorderad/Vorderrad, Haupteil/Hauptteil, gefühlos/gefühllos, freudschaftlich/freundschaftlich, as well as in Augenblich/Augenblick, wirchlich/wirklich, Klempfner/Klempner, wen/wenn, Nachtmal/Nachtmahl, or in Wohnungsuchen for ‘Wohnungssuche’.135

Regional variants can also be identified in the grammatical gender and case markers of substantives and/or other nouns, such as der Gehalt for ‘das Gehalt’ (salary), der Polster for ‘das Polster, der Pacht for ‘die Pacht’ (lease), der Pult for ‘das Pult’ (desk), der Akt for ‘die Akte’ (file), die Gedränge for ‘das Gedränge’ (crowd), das/die Erklärung (explanation), das/die Einladung (invitation), die/der Vorteil (advantage), der/die Brust (chest), der/die Tür (door), die Mädchen instead of das Mädchen (girl), die Weg instead of der Weg (path) etc., and the plural forms Pölster for ‘Polster’ (cushions), Bogen for ‘Bögen’ (arcs), Balkone for ‘Balkons’ (balconies), Lampione for ‘Lampions’ (lampions) etc. The substantives often lack –n in dative plural, as discussed above, while in this period the dative singular masculine and neuter still took the ending –e, as in im Dienste, zum Ausdrucke etc. One very distinctive area is that of the declension of articles, pronouns (ein/eine, ein/einen, ihn/ihm, ihn/ihnen, den/dem, niemanden/niemandem, jemanden/jemandem) and adjectives (mit ihn / lauten Lachen, um ihm / einem Prozeß, vor ihn / den Tor etc.) with apocope and/or without a difference made between –n and –m as well as the area of congruence in the nominal phrase (see below on syntax) with repetition of a gender marker (von einem fest zugeknöpftem Rock etc.) or with other local idiosyncrasies (keine eigentliche[n] Betten etc.).136

Verbs have regional forms, too, as in er lauft/läuft, er ladet ein, er fahrt for ‘er läuft / lädt ein / fährt’ (he is running / he is inviting / he is driving), as well as er erschreckt for ‘er erschrickt’ (he is scared), (er) ist gesessen / gestanden / gelegen, for ‘(er) hat gesessen / gestanden / gelegen’ (he was sitting / standing / laying), ich kauf for ‘ich kaufe’ (I am buying). The subordinate clause without an auxiliary, as in Karl der schon nahe daran gewesen [war] (Karl who had already been nearby),137 is usual in the written texts of this time as were the archaic but usual forms gieng(e), fieng, hieng for ‘ging, fing, hing’ (he walked / caught / hung) or giebt for ‘gibt’ (he gives). Southern German variants are also manifest in the derivation used in Kafka’s texts, such as Kontrollor for ‘Kontrolleur’ (inspector), probably also verständig for ‘verständlich’ (understandable), unaufschieblich for ‘unaufschiebbar’ (urgent), vorsichtlich for ‘vorsichtig’ (careful), gemeinschaftlich for ‘gemeinsam’ (together), and also in composition, such as Schweinsbraten for ‘Schweinebraten’ (pork roast) or -färbig/-farbig (coloured), as well as in idiosyncratic forms such as Werkstag for ‘Werktag’ (workday), Zugsverbindung for ‘Zugverbindung’ (train connection), Fabrikschef of ‘Fabrikchef’ (factory director), Fensternrand for ‘Fensterrand’ (window frame) etc.138

Last but not least, there are many specific syntactic forms, mentioned above in connection with congruence, and specific prepositional and verb patterns, such as auf einen Augenblick for ‘für einen Augenblick’ (for a moment), nahe dem Ausgang for ‘nahe am Ausgang’ (close to the exit), Freude von solchen Erfolgen for ‘Freude an solchen Erfolgen’ (joy at such success), in Franz stoßen for ‘an Franz stoßen’ (encounter Franz), auf jemanden vergessen for ‘(an) jemanden vergessen’ (forget someone), es steht nicht dafür for ‘es lohnt sich nicht’ (it is not worth it) etc.139 The area of syntax is still wide open for further exploration. This includes analysis, with an eye to Prague, Bavarian and Austrian varieties of German from the perspective of orality and language contact, of Kafka’s use of specific prepositional and verbal patterns, congruence within nominal phrase and sentence, word order, sentences without explicit subject (pro-subject) and the reflexive sich, as well as his use of definite and indefinite articles and articles following prepositions.

It is true that there are instances where Kafka’s German seems shaky in orthography, genus, derivation and syntax, but that was typical of a period in which standard German was not yet stabilized. It is also undeniable that his official and literary texts contain variants typical for Austria or South Germany, but this is hardly surprising. An analysis of Kafka’s German and comparison with his German-speaking contemporaries in Austria, Bohemia and Prague does not in fact reveal any significant differences. Both lexical and non-lexical Austrianisms in the official language and elsewhere reflect the linguistic and political situation of his time, when Austrian German was becoming established as the standard used in the territory of the Habsburg monarchy. It is self-evident that these Austrianisms are not an indication of inadequate, but only of different German. Moreover, Kafka’s writings show elements of dialect (article indifference, weakened declension, agreement in attribute. . .) both in official texts and in the manuscripts of his literary texts. The frequency of some phenomena, such as compounds with and without an interfix -s/Ø etc.,140 needs further evaluation. On the basis of earlier analyses as well as the present account, we can say that Kafka was proficient in his German: he used ‘standard’ forms in official and ‘non-standard’ forms in private letters, and he could correctly navigate between different varieties. The linguistic sobriety of his literary texts, sometimes explained in terms of the supposed isolation of the Prague idiom as a matter of poverty and inadequacy, was actually a conscious semantic gesture on Kafka’s part.141

1 Marek Nekula, „. . .v jednom poschodí vnitřní babylonské věže. . .“ Jazyky Franze Kafky (‘. . .on one Floor of the Inner Tower of Babel. . .’ Franz Kafka’s Languages). Prague: Nakladatelství Franze Kafky 2003, pp. 124–186, as well as Marek Nekula, Franz Kafkas Sprachen „. . .in einem Stockwerk des innern babylonischen Turmes. . .“ (Franz Kafka’s Languages. ‘. . . on one Floor of the Inner Tower of Babel. . .’). Tübingen: Niemeyer 2003, pp. 81–126.

2 See Pavel Eisner, Německá literatura na půdě ČSR. Od r. 1848 do našich dnů (German Literature in Czechoslovakia: from 1848 to the present). In: Československá vlastivěda (Encyclopaedic information on Czechoslovakia). Vol. VII: Písemnictví (Literature). Prague: Sfinx, 1933, pp. 325–377; Heinz Politzer, Problematik und Probleme der Kafka-Forschung (Themes and problems in Kafka research). Monatshefte für deutschen Unterricht, deutsche Sprache und Literatur 42 (1950), pp. 273–280; Klaus Wagenbach, Franz Kafka. Reinbek b. Hamburg: Rowohlt 1964: 55 f. etc. For a critical view see e.g. Pavel Trost, Das späte Prager Deutsch. Pozdní pražská němčina (Late Prague German). Germanistica Pragensia 1 (1962), pp. 31–39, here p. 37, Pavel Trost, Franz Kafka und das Prager Deutsch. Franz Kafka a tzv. pražská němčina (Franz Kafka and so-called ‘Prague German’). Germanistica Pragensia 2 (1964), pp. 29–37; Hartmut Binder, Entlarvung einer Chimäre: Die deutsche Sprachinsel Prag (Unmasking a chimera: Isolated German in Prague). In: Maurice Godé – Jacques Le Rider – Françoise Mayer (eds), Allemands, Juifs et Tchèques à Prague de 1890 1924. / Deutsche, Juden und Tschechen in Prag 1890–1924. Montpellier: Bibliothèque d’Études Germaniques et Centre-Européennes, 1994, pp. 183–209; Hartmut Binder, Paul Eisners dreifaches Ghetto (Paul Eisner’s triple ghetto). In: Michel Reffet (ed.), Le monde de Franz Werfel et la morale des nations. / Die Welt Franz Werfels und die Moral der Völker. Berlin et al.: Peter Lang, 2000, pp. 17–137.

3 See also Marek Nekula – Verena Bauer – Albrecht Greule (eds), Deutsch in multilingualen Stadtzentren Mittel- und Osteuropas. Um die Jahrhundertwende vom 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert (German in Multinational Cities in Central and East Europe. Around the Fin de Siècle from the 19th to the 20th Century). Vienna: Praesens 2008.