DIVIDED CITY:

FRANZ KAFKA’S READINGS OF PRAGUE

INTRODUCTION

During the second half of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th, a number of monuments appeared on Prague’s squares, embankments and hilltops that were linked with national ideology. They were erected by nationalist-minded groups with the aim of increasing their visibility in the public sphere and winning over those whose support was only lukewarm. Language and ethnicity took precedence over other values and shaped not only the programs of political parties, but decisions on the individual level such as choosing a school for one’s children. Yet while the Czech nationalists campaigned for parity between the two languages and communities in Bohemia, the Germans wanted to preserve the status quo. Over time, nationalists on both sides increasingly desired separation, particularly in the urban environment.

One way of controlling public space was to hold meetings and demonstrations, including ‘national funerals’. The first of these, in 1847, was that of Josef Jungmann. In the 1860s national funerals came to play an important part in rallying support for the nationalist cause and enhancing its organization. Another option for appropriating public space, as already noted, was to erect monuments and grand public buildings or name (or rename) streets and squares after eminent figures in the national movement. The transformation of public space went hand in hand with the transformation of the public sphere. According to Jürgen Habermas, the representative public of the feudal age evolved into a participative public that grew out of bourgeois salons (and later cafés), museums, galleries, concert halls and theatres staging bourgeois dramas that were commented on through the nascent genre of criticism.1 An important element in the formation of the modern public was literary culture, which as well as books comprised literary journals, press reviews, publishing houses and reading circles.

Habermas dates the creation of a public sphere in Paris to the years between 1680 and 1730. A similar process took place later in Bohemia and Prague, though more slowly in the Czech community than in the German-speaking. The mobilization of a Czech nationally oriented public in the Prague public sphere together with the creation of monuments and public buildings gained momentum towards the end of the century with a whole series of projects dedicated to the nationalist cause: the Palacký Bridge, the Czech National Theatre, the Slavonic pantheon Slavín, the new Museum building, the Municipal House, and the monuments to František Palacký and Jan Hus, to name the most prominent. Post-1918, German monuments in Prague were deliberately neglected, new ones were not allowed, and some were even removed or destroyed.2 The Jewish Town was largely destroyed during the reconstruction of Prague at the turn of the century and architectonically integrated into the city as a whole.

Conceptually, Prague’s monuments can be read as ‘texts’ that interlink national themes, values and symbols (the Libuše legend, Hussitism) with public spaces and with each other, providing an impulse and a setting for the mobilization and manifestation of nationalist support. Through them, the Czech national movement took possession of public space and put across its message to its ‘readers’. Through these ‘messages’ – and of course through the imaginative force of Czech literature – Prague gradually defined itself as an icon of Czechness, or Czecho-Slavism, and became its intricately structured ‘monument’. This was an alternative Prague that one could identify with – but also criticize or simply reject.

KAFKA’S ‘SMALL PRAGUE’

In this chapter, I will attempt to elucidate Franz Kafka’s reading and narration of Prague. In this endeavour, I consider both his literary and non-literary texts and place particular emphases on his correspondence with friends. The topography of Prague appears in Kafka’s diaries and letters in two forms: 1) as a localization in references to people, things and events; and 2) as the subject of Kafka’s observations and deliberations. Here I am less concerned with Prague as a referential space than with the significance Kafka attaches to it.

It should be said at the outset that Prague is mentioned far less often in Kafka’s diaries and letters than its importance for him would lead us to expect. This may be simply because the city formed the invisible backdrop of his daily life. Quoting Kafka, Josef Čermák actually sees Prague as Kafka’s synonym for the habitual and commonplace:3

If you, Felice, are in any way to blame for our common misfortune (omitting for the moment my own share, which is monumental), it is for your insistence on keeping me in Prague, although you ought to have realized that it was precisely the office and Prague that would lead to my – thus our – eventual ruin. I don’t say you wanted to keep me here deliberately, this is not what I think; your ideas about possible ways of life are more courageous and more flexible than mine (I am up to the waist in Austrian officialdom, and over and above that in my own personal inhibitions), so you did not have any compelling urge to consider the future carefully. All the same you ought to have been able to assess or at least to sense this in me, even against myself, even contrary to my own words. [. . .] What happened instead? Instead we went to buy furniture in Berlin for an official in Prague. / Heavy furniture which looked as if, once in position, it could never be removed. Its very solidity is what you appreciated most. The sideboard in particular – a perfect tombstone, or the memorial to the life of a Prague official – oppressed me profoundly. If during our visit to the furniture store a funeral bell had begun tolling in the distance, it wouldn’t have been inappropriate. I wanted to be with you, Felice, of course with you, but free to express my powers which you, in my opinion at least, cannot really have respected if you could consider stifling them with all that furniture.4

Their rarity makes such explicit references to Prague all the more significant and deserving of attention. Some critics even see Prague as the referential space and time rather than the fictional chronotope of Kafka’s literary texts. Pavel Eisner, as well as the authors of the Czech monograph Franz Kafka and Prague and some contributors to the first Kafka conference at Liblice in 1963, all interpreted Kafka’s work – as discussed in the first chapter – and Prague German literature as a whole from the ‘from the Prague perspective.’5

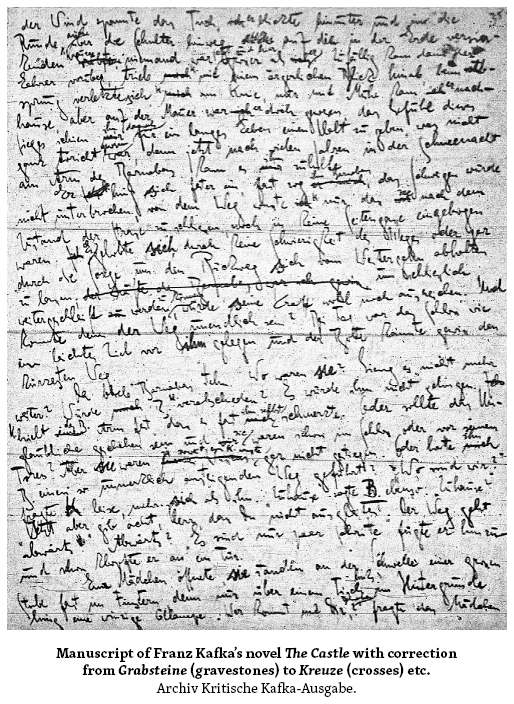

Especially Franz Kafka’s literary texts rarely refer explicitly to Prague’s topography, as for example in the cathedral scene in The Trial.6 Kafka plays – as Malcolm Pasley phrases it – his ‘semi-private games’, but in his stories he also avoids being over-specific. We may observe this shift away from the private and local atmosphere in the novel The Castle. When Kafka revised the original manuscript he replaced the first-person narrator with a third-person narrator; he also replaced ‘collapsing tombstones’, which could be associated with the Old Jewish Cemetery in Prague, with ‘collapsing crosses’, and ‘members of the community’ with ‘citizens’. Similarly, the experience of a local national fight for linguistically distinct spaces is transformed into a story about the confusion of tongues and thus made universal. Here the biblical myth becomes an allegory of a society divided along ethno-national lines.

In his non-literary texts, however, Kafka does make some explicit references to Prague. This is hardly surprising, since Kafka was born and bred in the city. He studied in Prague, worked there for fifteen years and spent most of his relatively short life there. Kafka’s thoughts never left Prague, even when he was living somewhere else. In December 1923, for example, when he was living in Berlin, he wrote the following (in Czech) in a note addressed to his sister Ottla and her husband Josef David:

And Ottla, please explain to our parents that I can only write once or twice a week; postage is already as expensive as it is at home. I am, however, enclosing Czech stamps for you to help you out a bit.7

The Czech words ‘u nás’ (at home, in our country) mean Prague, where Kafka had remained in thought even though he was in Berlin.

By then Prague was already the capital of the newly founded Czechoslovakia. It became ‘Greater Prague’ in 1920 after new legislation incorporated all the Czech suburbs. The small German-speaking minority living in the Old Town in the centre of this Central European metropolis thus became smaller and more inconspicuous than it had been before Czechoslovak independence in 1918. From Kafka’s point of view, however, Prague was not as large as the Czech majority seemed to think. From the window of his parents’ apartment in the Oppelt House on the Old Town Square he could survey the entire area in which he lived (parts of the Old Town and the remains of the Old Jewish Ghetto in his mental map). Shortly after World War I, he outlined this space for his friend Friedrich Thieberger with a small movement of his index finger:

Once when we were standing at the window and looking down on the Old Town Square, he pointed to the buildings and said: ‘My high school was here, the university there in the building you can see and a little further to the left my office.’ He made a few small circles with his finger. ‘My entire life is enclosed in this small circle.8

While Kafka may have indicated such a small space with his finger, he in fact lived and moved in a larger area of Prague, and many other places, streets and districts appear in his correspondence and diaries or are associated with him by his contemporaries. Kafka worked in the Workers’ Accident Insurance Company for the Kingdom of Bohemia in Prague on Na Poříčí Street, attended the German New Theatre in Vinohrady and the Czech National Theatre on the bank of the Vltava, climbed up Petřín hill, crossed the Charles Bridge to Prague Castle or to Kampa island. With his sisters he visited not only Troja, where he later went to work in the garden, but also Letná and Podskalí; he climbed up to Vyšehrad, went to the public swimming school on the bank of the Vltava, rowed on the Vltava, was responsible for the family factory in Žižkov, etc.9 He was also familiar with the environs of the city, as we know from his postcards to his friends and family.

The story told by Thieberger shows, however, that these are not the referential places Kafka understands as Prague. He points to and writes his Prague with a slight movement of his finger. That small movement of Kafka’s finger, stressing the words ‘enclosed in this small circle’ is rather Kafka’s reading and narrating of Prague. His gesture and words may evoke the opposition between the small German and German-speaking Jewish minority in Prague’s Old Town and the ‘Greater Prague’, in which the ‘ethnic Czechs’ had a twenty to one majority in most districts and the nationalist Czech middle classes controlled the city hall.

THE NARRATIVE OF BABYLON AND THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA

Friedrich Thieberger’s story of Kafka’s index finger may be particularly appealing because it shows that Franz Kafka ascribes to his space a semantic relevance. But it is perhaps too simplistic to believe that Kafka’s Prague is a specific ‘small’ space, or as Paul Eisner phrased it, a ‘triple’ social, national and confessional ghetto which entraps Kafka. In fact, Kafka never lived in a real Jewish ghetto. The Prague ghetto ceased to exist legally after 1848, and the area was largely demolished and rebuilt as part of the general urban modernization around 1900. Eisner’s postulate appears problematic also because Kafka obtained a regular education in Czech, had a good job in the public sphere and participated in German, Czech and Jewish culture in German, Czech, Yiddish and Hebrew. Rather, the foundations of Kafka’s ghetto were antisemitism (both individual and institutional) and the fear of violent pogroms, about which he read and which he and his friend Max Brod experienced in Prague. The fear of the violence he experienced in his native city never left his thoughts – no matter where he actually was, in Vienna, Munich, Flüelen, Paris or Berlin. Kafka would be able to answer the question in Prager Presse (Prague News): ‘Why did you leave Prague?’10 with the words: ‘I never left Prague’, which could be taken to mean, ‘I never lost my fear of the pogroms’. He found this fear also in Berlin, where he had hoped to lose it, as he wrote in a Czech text addressed to his brother-in-law Josef David:

Dear Pepa, be so good and write me a few lines should anything particular happen at home. [. . .] What are you doing now you don’t have anyone to scare about going to Berlin. Scare me, Pepa? That’s like Eulen nach Athen tragen (‘taking owls to Athens’ i.e. coals to Newcastle). And here it really is terrible living in the inner city, struggling to survive, reading the papers. None of which I do, of course, I wouldn’t last half a day, but out here it’s nice, just now and then some flash of news or fear finds it way to me which I then have to fight, but is it any different in Prague? How many dangers lurk there every day for the timid soul?11

The strong discursive polarization between Germans and Czechs along perceived linguistic-national lines, as well as anti-German sentiments, were a contributing factor to the pogroms in Prague, just as the language question had provoked the Badeni crisis in 1897. The Czech-German conflict over language occupied both Kafka’s and Max Brod’s thoughts. During a visit to Switzerland in August 1911, Brod noted in his diary:

In the men’s bathhouse. Very crowded. There are signs in an unusually large number of languages – the Swiss solution to the question of language. Everything is made confusing so that even a chauvinist doesn’t know what’s going on. First he finds German to the left, then to the right, German in connection with French or Italian or both or even with English, and German sometimes is missing completely. In Flüelen, it was prohibited in German-Italian to go on the train tracks. The slow passing of cars was in German-French. – Switzerland is certainly a school for statesmen!12

Franz Kafka makes a laconic remark on the same topic:

Max: Confusion of Tongues – the solution to national problems. The chauvinist doesn’t know what is going on anymore.13

Kafka considers the language situation in Switzerland and the German-French language conflict to be a form of the Confusion of Tongues at Babel, a situation he was familiar with from Prague and Bohemia generally. In the Old Testament, the story of the Tower of Babel represents the fragmentation of a linguistic, cultural and territorial whole into individual languages and clans:

Now the whole world had one language and a common speech. 2 As men moved east-ward, they found a plain in Shinar and settled there.

3 They said to each other, ‘Come, let’s make bricks and bake them thoroughly.’ They used brick instead of stone, and tar for mortar. 4 Then they said, ‘Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves and not be scattered over the face of the whole earth.’

5 But the LORD came down to see the city and the tower that the men were building. 6 The LORD said, ‘If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. 7 Come, let us go down and confuse their language so they will not understand each other.’

8 So the LORD scattered them from there over all the earth, and they stopped building the city. 9 That is why it was called Babel – because there the LORD confused the language of the whole world. From there the LORD scattered them over the face of the whole earth.14

The case of Bohemia was similar. Its territory was – or was perceived to be – divided into two exclusive (linguistic) worlds. Kafka returned to the Babel motif in September 1920 in his story ‘The city coat of arms’. Some time earlier, in February, the Czechoslovak language law and constitution had added fuel to the fire of the ‘Babylonian’ divisions in public life. The ‘Czechoslovak’ language (which meant both Czech and Slovak) became the official language of the new state. All other languages, especially German, were partially restricted in their use. The tender wound of language-based nationalism that had pained the Habsburg monarchy was suddenly torn open again.

It is not surprising, then, that Kafka read the Praguian coat of arms as the Tower of Babel, and vice versa:

[. . .] the second or third generation had already recognized the senselessness of building a heaven-reaching tower, but by that time everybody was too deeply involved to leave the town. All the legends and songs that came to birth in the city are filled with longing for a prophesied day when the city would be destroyed by five successive blows from a gigantic fist. It is for that reason too that the city has a closed fist on its coat of arms.15

Prague’s coat of arms also contains a huge gauntleted fist that can divide and destroy a city. There are, it is true, some differences between the Prague coat of arms and that of Babel in the story. Prague’s fist holds a sword, Babel’s does not. The fist in Prague’s coat of arms symbolizes defensive strength, whereas the Babel fist stands for destruction.16 Yet despite these differences the parallel is clear. Kafka does something similar in ‘The Stoker’, the first chapter of the novel The Man Who Disappeared, also known as ‘Amerika’. The ‘Statue der Freiheitsgöttin’ (literally ‘statue of the Goddess of Freedom’) holding a ‘sword’, ‘as if the goddess had just raised it, and the wind blew about her body without constraint’,17 is a very explicit allusion to the Statue of Liberty in New York – and is translated as such for example by Stanley Corngold18. The fact that the real statue is holding a burning torch does not detract from the parallel.

Unlike in the Bible story, the languages in ‘The city coat of arms’ are made confusing and divided even before the Tower of Babel is built. Kafka mentions ‘signposts’, ‘interpreters’ and separate ‘accommodation’ for the ‘workmen from various countries’, as well as ‘conflicts’ and ‘bloody fights’.19 In other words, Kafka’s Babel is already divided. And in this it evokes the divided Czech and German worlds in Bohemia, and especially in its capital, Prague, where the Czech and German communities existed side by side, sometimes peacefully but often also attacking each other in public discourse and perpetuating this discord through independent cultural and economic institutions and school systems.

Kafka had considered the true extent of the Tower of Babel’s foundations three years earlier, in 1917, in his story ‘Building of the Great Wall of China’. The foundations had to be enormous due to the tower’s height. The Tower of Babel was supposed to reach heaven; it was also the tower from which heaven could be stormed. Kafka’s word ‘Himmelsturmbau’ could be read in two ways in the German original: as ‘Himmel-Sturm-Bau’ but also as ‘Himmels-Turm-Bau’, that is, as a building from which heaven can be stormed, or as a tower reaching up to heaven.20 Kafka’s own ‘Tower of Babel’, the Workers’ Accident Insurance Company for the Kingdom of Bohemia in Prague, reaching to the heaven of Bohemian government administration (‘Statthalterei’), was at this time – around 1917 – planning to change its ‘Bohemian’ character and divide according to language into a German and a Czech company, to reinforce through this ‘Great Wall’ the stability of the entire state,21 just as Charles University (1882) and other institutions had been divided some time earlier.

In Kafka’s story ‘Building of the Great Wall of China’, a scholar questions the reason for the Tower of Babel’s destruction. He does not believe that the failure of the project was an act of providence, as it is presented in the Old Testament. He believes that the plan was doomed to fail due to the weakness of the foundations (‘the construction foundered, and was destined to founder, on the weakness of its foundations’). He says:

the Great Wall would create, for the first time in human history, a solid foundation for a new Tower of Babel. Ergo: first the Wall and then the Tower.22

In the context of the story, the narrator’s doubts about the scholar’s assertions are logical and understandable:

At the time, his book was in everyone’s hands, but I admit that even today I do not really know how he thought this Tower would be built. The Wall, which did not even describe a circle but only a sort of quarter- or semi-quarter, was supposed to provide the foundation for a Tower?23

How could the Great Wall serve as a foundation for the Tower of Babel, given its shape?

If we read this story through the lens of New Historicism in the discursive context of the Czech-German linguistic-national division in Bohemia, bearing in mind that the ‘Great Wall’ was a common metaphor for this division, the Great Wall now appears as a ‘true’ foundation for the new Tower of Babel, rather than an absurd exaggeration:

If anyone built the Great Wall, it wasn’t us. It is true that some of our intellectual leaders led us to be closer to Roman and Slavonic culture because they recognized the danger of the German mind’s influence on Czech culture [. . .] But there was no hatred of German culture in our country, there was only a healthy instinct for survival. Our nation would already have ceased to exist and we would have become Czech-speaking Germans, had we accepted the influence, the culture and the mind of our neighbour without reservation. We say yes to having contacts, but we say no to surrender.24

This is the Czech writer Viktor Dyk’s reply in the Czech literary journal Lumír to Franz Werfel’s article ‘Note on a celebration of Wedekind’, which had appeared on 18 April 1913 in the Prager Tagblatt (Prague Daily News). Viktor Dyk was already well known to Brod and Kafka in 1910. Czechs and most Germans were aware of Dyk’s strong nationalism and his phrase ‘I know our task is to either make Bohemia Czech or die’.25

If the ‘Great Wall’ is a metaphor for division along linguistic lines in contemporary national discourse, then the idea of the ‘Great Wall’ as the Tower of Babel’s foundation appears quite logical. The linguistic boundary between German and Czech in the Bohemia of this time can now be understood territorially and functionally as a Great Wall that both Czechs and Germans were industriously building. The division of nations will follow as a natural consequence of the division of language and its ‘foundations’. The story of the Confusion of Tongues at Babel, which leads to the division of the world into different countries, also reflects this separation. In Bohemia this resulted – or was expected to result – in the division of the once ‘transnational’ Bohemian society along ethno-national lines into German and Czech communities. Although in the Bible this absolute division comes only after divine intervention, in Prague it was a goal of nationalist politics, which sought to eliminate all moments of transition between language and national territories. Of course, there were no such clear borders in everyday linguistic practice. But they were, to various degrees, ‘under construction’ in the individual and official spheres, and in different territories. It is in this light that we should understand one of the narrator’s somewhat absurd assertions about the Great Wall of China, that it was built in parts – separate sections that did not form a whole. And we can also understand why Kafka rejected the Czech-Slavonic/German polarization associated with a monolingual interpretation of the world and one’s – or rather Odradek’s – identity in the story ‘The householder’s concern’.26

Against the metaphoric backdrop of the Great Wall, the division along linguistic lines – a linguistic border within Bohemia – can be seen as substantial enough to serve as the foundation for a new ‘Tower of Babel’, as mentioned in the Travel Diaries, where it means language-based national separatism. It is also substantial enough to serve as the foundation for the ‘new’ tower to storm heaven (‘Himmels-Turm-Bau’ as ‘Himmel-Sturm-Bau’) and destroy the ‘old’ divine order – the Austrian empire and its rule over Bohemia. In all of these cases (Babel, ‘Great Austria’,27 Bohemia) we see a violent destruction of a once homogenous territorial whole along its linguistic borders. However, this division was already present in their foundations: the multilingual Austrian empire ‘is’ a Babylon.

If the metaphorical Great Wall of the internal linguistic border is the foundation on which the division, the Tower of Babel, is metaphorically built, then the whole of Bohemia would be included in this Tower of Babel. The word ‘city’ (‘Stadt’) in Kafka’s story ‘The city coat of arms’ may thus be read as ‘state’ (‘Staat’). This is not only a pars-pro-toto figure (city for state), which is commonly associated with capital cities; it also connects narratives of the city (Babylon and Prague) with narratives of the state (China and Bohemia). Kafka frequently applies this strategy of double naming and reading to signal, for example, that the officials ‘Sordini’ and ‘Sortini’ in the novel The Castle can be understood as the same person, or at least as manifestations of one model. We saw this reading strategy also in the story ‘Building the Great Wall of China’ with the reading of the word ‘Himmelsturmbau’ as ‘Himmels-Turm-Bau’ and/or ‘Himmel-Sturm-Bau’.28

The metaphorical Great Wall of China, separation along linguistic and national lines, and Babylonian fragmentation divided the Bohemian Lands both territorially and functionally. It is irrelevant whether in the ‘city’ (‘Stadt’) Kafka was recalling the old Habsburg ‘state’ (‘Staat’) or whether he meant the new Czechoslovak ‘state’ (‘Staat’). The second interpretation seems more probable considering that the story was written in 1920 and in the future tense. Czechoslovakia, just like the Habsburg state, will collapse as a result of linguistically oriented nationalism. Its destruction ‘by a huge fist in five short blows’ will also be anticipated by some people with great ‘longing’.29

This longing for self-destruction may appear rather unhealthy. In a letter to Max Brod, Kafka connects his own states of anxiety with the motif of the Tower of Babel and the confusion of tongues when he mentions his ‘inner Tower of Babel’.30 Incidentally, Kafka considered this anxiety to be the real reason for his illness in 1917, which was accompanied by serious thoughts of suicide. After the crisis in his relationship with Milena Jesenská, a personal crisis exacerbated by the pogroms of 1918 and 1920, these states of anxiety culminated in a nervous breakdown.

PRAGUE STEEPED IN MYTH

The Prague that Kafka knew so well and read as a new Babel – as he did the whole of divided Bohemia – was swept by language-based nationalism. This division was clearly visible in the Prague public sphere, which gradually came to be dominated by national monuments and grand ‘representative’ buildings, as we mentioned at the start of this chapter. Some historic monuments were now read as national monuments, notably the Charles Bridge, Prague Castle and Vyšehrad.31 In the latter part of the 19th century, the Prague public space was claimed by both Czech (Slavonic) and German nationalists, a fact reflected in the following well-known passage from a letter Kafka wrote in 1902:

Prague doesn’t let go. Either one of us. This old crone has claws. One has to yield, or else. We would have to set fire to it on two sides, at the Vyšehrad and at the Hradčany, then it would be possible for us to get away.32

We can recognize two elements in this quote. Prague appears as a mythic Siren,33 and Prague’s Castle and Vyšehrad hill are placed in a semantic opposition. The ‘Czech’ (Slavonic) Vyšehrad can be seen as an opposition to Prague Castle, which at this time was often seen as a symbol of official (Habsburg, ‘German’) authority.

Vyšehrad is a large hill in Prague above the River Vltava. Since the time of national rebirth, it had been seen as the sacred core of a Slavonic/Czech territory. In the Green Mountain Manuscript, written in Czech, it was closely associated with Libuše, a female ancestor of the Přemyslid (Slavonic/Czech) dynasty and of the Bohemian, Slavonic/Czech state, who prophesied the coming fame (‘sláva’!) of Slavonic Prague.34 Indeed, legend has it that she founded the city. Both the first Přemyslid king Vratislav and some later Přemyslid princes reigned from Vyšehrad. This mythic dimension of Vyšehrad explains why it was chosen as the site of the Czech pantheon Slavín. The Czech writer Julius Zeyer was the first person to be buried in the Slavín crypt in 1901, one year before Kafka wrote his sentence about Vyšehrad and Prague Castle. In his story Inultus, Zeyer connected the Czech myth of national death and rebirth with the story of the suffering, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. The resurrection in Christ and the resurrection in language come together in the inscription on the crypt: ‘Although they have died, they still speak’ – not ‘live’, as Christians would say. Already in 1863, the tombstone of Václav Hanka in the Slavín crypt had been decorated with a similar inscription that manifested the ideology of Czech national rebirth and equates language and nation: ‘Nations will not die as long as their language continues to live’. Kafka knew the modern Czech myth of national death and rebirth, which played a key role in the narrative division of Bohemian society into ethno-national communities and connected it symbolically with Vyšehrad.

He encountered this ideology not only at Slavín but also earlier in his Czech classes at the German grammar school on the Old Town Square, as well as in other contexts. One of them was the Czech National Theatre, which Kafka visited repeatedly. The national myths, as well as an imagined separate national space, are inscribed in the paintings in the foyer of the theatre. The resurrection myth is depicted in the triptych on the foyer ceiling. A separate linguistic space emerges in the lunettes around the foyer. Here, in a series of scenes named after specific locations in Bohemia, we see various episodes in the life of the ‘Slavonic hero’, who patrols the confines of the Czech ‘national space’, defending it against hostile nations and with his movement thus also ‘narrating’ the nation’s geographical boundaries: the first of the lunettes is actually entitled ‘Narration’, the second ‘Guardian of the Frontier’. The hero’s journey ends in the last lunette, named Žalov (‘Place of Grief’). The resting-place of the nation’s great, Slavín, was also known as Žalov, to which it is conceptually and architecturally related. In both cases, the name Žalov emphasizes grief rather than pride in the deeds of the nation’s heroes. On his visits to Slavín, Kafka will certainly have noticed František Bílek’s statue Grief on the tomb of Václav Beneš Třebízský.35

We now come to the second part of the opposition, the second place Kafka wanted to set on fire. Hradčany is the Castle District, built on a large hill that dominates Prague on the other side of the Vltava. The emperors Charles IV and Rudolf II made it their capital, the latter residing here during his visits to Prague from Vienna. Up until 1918, the Castle was thus a symbol of official (Habsburg, ‘German’) authority, especially for the German-speaking community. Kafka too, like other Germans living in Prague, considered the Castle of Prague to be the ‘emperor’s castle’.36 In similar fashion, the Czech National Theatre, symbol of a successful Czech national rebirth, was understood with respect to its national iconography and political program (autonomy for Bohemia, equality for Germans and Czechs) as antipodal to Prague Castle. The roof of the Czech National Theater could be read as an allusion to the roof of the Belvedere on the other side of the river near the Castle. In Prague public space the Czech National Theater with its monolingual ideology thus stands in semantic opposition to Prague Castle and confidently measures up against the ‘German’ Emperor’s Castle, trying likewise to appropriate it this way.

These two hills loaded with national, monolingual semantics – Vyšehrad with the Czech/Slavonic pantheon Slavín on the right and Hradčany with the Emperor’s Castle on the left bank of the Vltava – enclose the city of Prague, which Kafka sketched with a slight movement of his index finger as a small circle in which he feels trapped. Kafka, who also constructs an intertextual connection between Prague (with ‘claws’) and Sirens (with ‘claws’) in the story ‘The silence of the Sirens’, reads Prague as a Siren that he cannot escape. This mythic reading of Prague allows us to understand these two hills in Prague as Scylla and Charybdis, between which Odysseus had to navigate in the Odyssey when he was escaping from the Sirens.

Thus, just as the myth of Scylla and Charybdis teaches us that escape is impossible, it is impossible to escape the Siren Prague, who encircles the narrator and appears misleadingly pleasant but at the same time represents the fear of violence and pogroms. In fact it is as impossible to escape from Scylla and Charybdis as from the German-Czech battle over language with its monolingual ideology that dominated public discourse, institutions and public space in Bohemia and Prague. The only way out is an act of desperation: to set fire to Prague as Kafka proposed in the letter to Oskar Pollak. Without Odysseus’s tricks, the only alternative is to sink into the swirling water between Scylla and Charybdis. Kafka describes this submersion into water in the story ‘The judgment’ (1912/1917), which I will return to later.

KAFKA’S READING OF NATIONAL MONUMENTS

We can already see, however, that Kafka does more than merely reflect on the issues of national polarization along linguistic lines, the German-Czech language conflict and the national annexation of public space by national monuments – he emphatically rejects them. In a letter to Max Brod, Kafka evaluates a monument with a very strong nationalistic program. His critique is motivated not by the monument’s subject but by the lack of aesthetic value that results from blind nationalism:

It is a wanton and senseless impoverishment of Prague and Bohemia that mediocre stuff like Šaloun’s Hus or wretched stuff like Sucharda’s Palacký are erected with all honours [. . .].37

The monument to František Palacký, the nineteenth-century Czech historian and leader of the Czech national movement, on the Palacký Bridge was, by virtue of its theme, placement and iconography, not only a reflection and expression of Czech national ideology but also a public place where monolingual national agitation could be staged and motivated. And it was certainly with these aims in mind that the monument was erected in 1912 and unveiled during the 6th meeting of the patriotic Sokol gymnastics movement in Prague.38

The Palacký Bridge was built from stone in the Czech colours of protest (white-red-blue), named after Palacký and adorned with statues of ur-Slavonic ‘heroes’. Early Slavonic (Czech) history and the present are thus connected. On one of the bridgeheads stood a statue of the mythical Libuše and Přemysl; on the other, a monument to František Palacký himself. In discussing the Green Mountain Manuscript, Palacký described the age of Libuše as a time of autonomous and democratic Slavonic paganism that preceded the arrival of western Christianity from Germanic Bavaria and Saxony, projecting the values of cultural and political autonomy and democratic equality into Libuše’s era as well as into the era of Hussitism and the Reformation. According to Palacký, these values defined the course of Czech history and thus set out the political program for contemporary Czech politics (from Libuše’s era through the era of Hussitism to the national rebirth and the present). So Palacký’s name became in this special and simplified sense a byword for Czech national politics based on a monolingual national ideology and territorial claims (‘The Bohemian/Czech Lands for the Czechs’), as expressed in the lunettes in the foyer of the Czech National Theatre.

The Palacký Bridge, the second stone bridge in Prague after the Charles Bridge, became engaged in a polemical dialogue with its mediaeval counter-part based on its iconography. The statues on the Charles Bridge (and consequently the bridge as a whole) were at this time read as an icon of the Counter-reformation after the Battle of White Mountain (1620), of domination by the Catholic Habsburg dynasty (or any foreign power), of the empire (Reich) and of German culture. This is why the German population could identify with this bridge and why it was unacceptable to 19th century Czech nationalist ideology (František Palacký, Jaroslav Goll)39 – an ideology founded on an anti-Catholic, Protestant (democratic) understanding of the ‘national rebirth’ that had overcome the nation’s ‘death’ (period of darkness) after the Battle of White Mountain and the subsequent recatholicization and Germanization of the country.

As with Vyšehrad and the Emperor’s Castle, the two bridges display opposing iconographies. Kafka must have been aware of this on his walks through Prague. Like other German-speaking Praguians in the city, he began his walks at the Charles Bridge,40 crossed over to the predominantly German Lesser Town with its monument to the Austrian marshal Radetzky (which was torn down after 1918), and walked up to the Castle. By contrast, Czechs from the New Town or the predominantly Czech suburbs of Nusle or Podskalí would go for walks to Vyšehrad; and if they went there from the Czech district of Smíchov, they would cross the Palacký Bridge.

Between 25 and 29 May 1920 Kafka writes in a letter to Milena Jesenská:

Some years ago I often went rowing on the Moldau [= Vltava] in a maňas (small boat), I would row upstream and then float down with the current underneath the bridges, completely stretched out.41

Knowing how acutely aware Kafka was of Prague’s national iconography, we can imagine that when he sees the bridges from underneath, it is as if he were seeing the ideologies concealed within their iconography.

Against this background, the bridge motif that ends Kafka’s ‘The judgment’ deserves particular attention. Kafka wrote this story in September 1912, only two months after the monument to Palacký was placed at the head of Palacký Bridge. At roughly the same time, occasioned by the census of 1910, his family was pondering the question of its own national identity, while Kafka himself was commenting in his Travel Diaries on the complexity of the language situation in Switzerland viewed from the perspective of the language conflict in Bohemia, as I mentioned at the start of this chapter. This was also shortly after Kafka’s Jewish ‘rebirth’ at around the end of 1911. Kafka’s story could be read as a polemic against the program of assimilation, which the generation of fathers stood for, the bridge motif being a polemic against German and Czech national self-portrayals.

Hartmut Binder connects the bridge in ‘The judgment’ with the Svatopluk Čech Bridge, which was built between 1905 and 1908.42 For Kafka’s contemporaries this bridge symbolized the opening up of the rebuilt Jewish ghetto onto the banks of modernity. Kafka, however, associates this bridge with failure and suicide. While the statues on the Charles and Palacký Bridges embody opposing fossilized national agendas, which German and Czech nationalist students loudly defended in street battles, the fleeting shadow of the suicide Georg Bendemann darts quietly over the ‘Jewish’ bridge in the ‘The judgment’. In ‘a simply endless stream of traffic’, Georg Bendemann falls quietly, covered by the noise of a passing bus, from the bridge parapet into the river43 after his revolt against his father has failed, not unlike his former friend whose attempt to become a part of the ‘colony of his compatriots in Russia’ (which could mean the Jews), also came to naught.44 Whereas in the first instance the allusion is to the policy of Jewish assimilation personified by Kafka’s father, the second hints at the limits of Zionism. By committing suicide, Bendemann points to a third solution to the insoluble dilemma of being a Jew faced with the Scylla and Charybdis of German and Czech nationalism accompanied by antisemitism, which in 1918–20 came to an ugly head in pogroms on the streets of Prague and, as Kafka observed in a letter to Milena written between 17 and 20 November 1920, poisoned the atmosphere of the city:

I’ve been spending every afternoon outside on the streets, wallowing in antisemitic hate. The other day I heard someone call the Jews ‘prašivé plemeno’ (‘a mangy race’).45

In his literary texts, however, the echoes of the discourse of the day are less audible – though audible nonetheless. Although the story ‘Gracchus the hunter’ (1917) is associated with Riva in Italy, the very name Gracchus (= jackdaw = kavka/Kafka) relocates it in Prague, thus evoking the monuments and their functions in the public space of the city:

Two boys were sitting on the harbour wall playing with dice. A man was reading a newspaper on the steps of the monument, resting in the shadow of a hero who was flourishing his sword. A girl was filling her bucket at the fountain. A fruit-seller was lying beside his wares, gazing at the lake. [. . .] A man in a top hat tied with a band of black crêpe now descended one of the narrow and very steep lanes that led to the harbour. He glanced around vigilantly, everything seemed to distress him, his mouth twisted at the sight of some offal in a corner. Fruit skins were lying on the steps of the monument; he swept them off in passing with his stick.46

At first sight the monument appears as an unmarked, semantically ‘dead’ and empty part of an everyday scene: two boys play around it, discarded fruit peel lies on its steps. Yet at the same time the ideological semantics of the monument are potentially present in the irritable gesture of the old man, for whom the fruit skins are an insult to its importance – which is in turn evoked and reinforced by the newspaper the man is reading on the steps of the monument ‘in the shadow of a hero who was flourishing his sword’. The depiction of the setting is so non-specific that it could be in any other city, except that it would be a different hero with a different sword pointing in a different direction, but in both cases dividing the world by nationalism.

So it is that, in those of Kafka’s literary texts that take up the thread of contemporary public discourse, the small circle Thieberger watched him draw with his index finger is confronted with a space and a world divided by the Great Wall of China, the Babel of linguistic confusion, and the Scylla and Charybdis of Czech and German nationalism represented by (inter alia) the opposing icons of Vyšehrad and Prague Castle, and the monuments of warriors whose weapons cast their shadows on the printed media where public debate is conducted. In doing so he realigns the axis of Czech-German polarity, generalizing it into myth and thus lending his local ‘Prague’ stories universal validity.

1 See Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Translated by Thomas Burger with the assistance of Frederick Lawrence. Cambridge/Mass.: MIT Press 1989, pp. 31–56.

2 See Cynthia Paces, Prague Panoramas: National Memory and Sacred Space in the Twentieth Century. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 2009; Marek Nekula, Prague Funerals: How Czech national symbols conquered and defended public space. In: Julie Buckler – Emily D. Johnson (eds), Rites of Place: Public Commemoration in Russia and Eastern Europe. Evanston/Illinois: Northwestern UP 2013, pp. 35–57.

3 Josef Čermák, Kafka a Praha (Kafka and Prague). In: Walter Koschmal – Marek Nekula – Joachim Rogall (eds), Češi a Němci. Dějiny – kultura – politika (Czech and Germans. History – Culture – Politics). Praha: Paseka 2001, pp. 158–170, here p. 169.

4 Franz Kafka to Felice, probably mid-February 1916 (March in the English edition). Franz Kafka, Letters to Felice. Translated by James Stern and Elizabeth Duckworth. London: Vintage 1999 (first publ. by Schocken, New York 1967), p. 501.

5 See Pavel Eisner, Německá literatura na půdě ČSR od r. 1848 do našich dnů (German Literature in Czechoslovakia: from 1848 to the present). In: Československá vlastivěda (Encyclopaedic information on Czechoslovakia), Vol. VII: Písemnictví (Literature), Prague: Sfinx 1933, pp. 325–377; Franz Kafka a Praha. Vzpomínky, úvahy, dokumenty (Franz Kafka and Prague. Memories, Reflections, Papers). Prague: Žikeš 1947; Eduard Goldstücker – František Kautman – Pavel Reiman (eds), Franz Kafka: liblická konference 1963 (Franz Kafka: Liblice Conference 1963). Prague: Academia 1963.

6 For a more detailed study see also Čermák, Kafka a Praha, pp. 217–235.

7 Franz Kafka, Briefe an Ottla und die Familie (Letters to Ottla and Family). Ed. by Hartmut Binder and Klaus Wagenbach. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1974, p. 151. My emphases.

8 Friedrich Thieberger, Kafka und die Thiebergers (Kafka and the Thiebergers). In: Hans-Gerd Koch (ed.), ‘Als Kafka mir entgegen kam. . .’ Erinnerungen an Franz Kafka (‘As Kafka approached me.’ Recollections of Franz Kafka). Berlin: Wagenbach 1995, pp. 128–134, here p. 133.

9 See Franz Kafka, Tagebücher (Diaries). Ed. by Hans-Gerd Koch, Michael Müller and Malcolm Pasley. 4 vols. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1990; Franz Kafka, Briefe (Letters). Vol. 1–4. Ed. by Hans-Gerd Koch. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer Verlag 1999, 2001, 2005, 2013; Hartmut Binder, Kafka-Handbuch in zwei Bänden (A Kafka Manual in two Volumes). Stuttgart: Kröner 1979; Klaus Wagenbach, Kafkas Prag. Ein Reiselesebuch. Berlin: Wagenbach 72004 (English version: Kafka’s Prague: A Travel Reader. Translated by Shaun Whiteside. Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press 1996); Hans-Gerd Koch (ed.), „Als Kafka mir entgegen kam. . .“: Erinnerungen an Franz Kafka (‘As Kafka approached me.’ Recollections of Franz Kafka). Berlin: Wagenbach 1995, etc.

10 See Kurt Krolop, Studien zur Prager deutschen Literatur. Festschrift zum 75. Geburtstag (Studies on Prague German Literature). Ed. by Klaas-Hinrich Ehlers, Steffen Höhne, Marek Nekula. Vienna: Edition Praesens 2005, pp. 89–102.

11 Franz Kafka to Josef David, 3 October 1923. – See Kafka, Briefe an Ottla und die Familie, p. 135 f.

12 Max Brod in Franz Kafka, Reisetagebücher in der Fassung der Handschrift (Travel Diaries Based on the Handwritten Manuscripts). Ed. by Hans-Gerd Koch. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1994, p. 123.

13 Kafka, Tagebücher, p. 950.

14 Genesis 11: 1–9.

15 Franz Kafka, The Complete Short Stories of Franz Kafka. Ed. by Nahum N. Glazer. London: Random House Vintage 1999, p. 434.

16 See also Hans Dieter Zimmermann, Der Turmbau zu Babel (Building of the Tower of Babel). In: Hans Dieter Zimmermann, Der babylonische Dolmetscher: Zu Franz Kafka und Robert Walser (The Babylonian Translator: on Franz Kafka and Robert Walser). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp 1985, pp. 61–66, p. 64.

17 See Franz Kafka, Ein Landarzt und andere Drucke zu Lebzeiten (A Country Doctor and Other Texts Published in his Lifetime). Ed. by Hans-Gerd Koch. Vol. 1, Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1994, p. 55. Translation: Franz Kafka, Stories 1904–1924. Translated by J. A. Underwood, foreword by Jorge Luis Borges. London: Abacus 1995, p. 59.

18 See Franz Kafka, Selected Stories. Edited and translated by Stanley Corngold. New York, London: W. W. Norton & Co. 2005, p. 12.

19 Franz Kafka, Zur Frage der Gesetze und andere Schriften aus dem Nachlaß in der Fassung der Handschrift (On the Question of Laws and Other Literary Remains Based on the Handwritten Manuscripts). Ed. by Hans-Gerd Koch. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1994, pp. 143–144; Kafka, The Complete Short Stories, p. 433. For more on the differences between the Bible story and Kafka see Zimmermann, Der Turmbau zu Babel, pp. 61–62.

20 Kafka, Zur Frage der Gesetze, p. 143, 147; see also Zimmermann, Der Turmbau zu Babel, p. 62; Peter Demetz, Praha a Babylón (Prague and Babel). In: Peter Demetz, České slunce a moravský měsíc (Czech Sun and Moravian Moon). Ostrava: Tilia 1997, pp. 76–77.

21 See Marek Nekula, Franz Kafkas Sprachen. „. . .in einem Stockwerk des innern babylonischen Turmes. . .“ (Franz Kafka’s Languages. ‘. . . on one floor of the inner Tower of Babel. . .’). Tübingen: Niemeyer 2003, pp. 163–173.

22 Kafka, Selected Stories, p. 116. My emphases.

23 Kafka, Selected Stories, p. 116.

24 Viktor Dyk, Němci v Čechách a české umění (Germans in Bohemia and Czech art). Lumír – měsíční revue pro literaturu, umění a společnost 42 (1914), May, No. 8, pp. 331–336, p. 332. See also Krolop, Studien zur Prager deutschen Literatur, pp. 81–84.

25 Podiven (= Milan Otáhal, Petr Pithart, Petr Příhoda), Češi v dějinách nové doby (Pokus o zrcadlo) (The Czechs in the History of Modern Times: An Attempt at a Mirror). Prague: Rozmluvy 1991, p. 364.

26 See Marek Nekula, Franz Kafkas Sprachen und Identität (Franz Kafka’s languages and identity). In: Marek Nekula – Walter Koschmal (eds), Juden zwischen Deutschen und Tschechen. Sprachliche, literarische und kulturelle Identitäten (Jews between German and Czechs: Linguistic, Literary and Cultural Identities). Munich: Oldenbourg 2006, pp. 135–158.

27 See Franz Kafka, Beim Bau der chinesischen Mauer und andere Schriften aus dem Nachlaß in der Fassung der Handschrift (Building of the Great Wall of China and Other Literary Remains Based on the Handwritten Manuscripts). Ed. by Hans-Gerd Koch. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1994, p. 64.

28 For the Czech-German double reading of the name ‘Klamm’ in The Castle see Hans Dieter Zimmermann, Das Labyrinth der Welt: Kafka und Comenius (The Labyrinth of the World: Kafka and Comenius). In: Klaas-Hinrich Ehlers et al. (eds), Brücken nach Prag. Deutschsprachige Literatur im kulturellen Kontext der Donaumonarchie und der Tschechoslowakei (Bridges to Prague: German-written Literature in the Cultural Context of the Habsburg Monarchy and Czechoslovakia). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang 2000, pp. 309–319; for readings of the name ‘Odradek’ in the story ‘The householder’s concern’ see in this book the chapter ‘The “being” of Odradek: Franz Kafka in his Jewish context’, p. 37 f.

29 We can also read it as a longing for the apocalypse, after which the new messianic world will arise. See Zimmermann, Der Turmbau zu Babel.

30 Franz Kafka to Max Brod, 29 August 1917. – See Max Brod – Franz Kafka, Eine Freundschaft. Briefwechsel (A Friendship: Correspondence). Ed. by Malcolm Pasley. Vol. 2. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 1989, p. 159. Kafka also connects his writing process with the motif of the Tower of Babel, seeing a parallel between writing and building the Tower. He did not, of course, compose his texts as integrally constructed novels as we typically find in 19th century fiction. His texts are horizontally scattered fragments, as is typical for modern texts such as Rilke’s ‘Die Aufzeichnung des Malte Laurids Brigge’. Such fragments are the scattered foundation blocks of the Tower of Babel, which is formed by the partially built Great Wall as mentioned in Kafka’s text ‘Building the The Great Wall of China’. Nor does the castle in Kafka’s text The Castle appear in the unified form of a castle (with a tower); rather it is scattered throughout buildings in the village.

31 See Marek Nekula, Die deutsche Walhalla und der tschechische Slavín (The German Walhalla and the Czech Pantheon Slavín). In: brücken. Germanistisches Jahrbuch Tschechien – Slowakei. NF 9–10 (2003), pp. 87–106; Michaela Marek, ‘Monumentalbauten’ und Städtebau als Spiegel des gesellschaftlichen Wandels in der 2. Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts (Monuments and urbanization as a reflection of social change in the second half of the 19th century). In: Ferdinand Seibt (ed.), Böhmen im 19. Jahrhundert: Vom Klassizismus zur Moderne (Bohemia in the 19th Century: From Classicism to Modernity). Frankfurt am Main, Berlin: Propyläen 1995, pp. 149–233, 390–411; Michaela Marek, Kunst und Identitätspolitik. Architektur und Bildkünste im Prozess der tschechischen Nationsbildung (Art and Identity Politics: Architecture and Visual Arts in the Process of Czech National Building). Weimar, Cologne, Vienna: Böhlau 2004; Zdeněk Hojda – Jiří Pokorný, Pomníky a zapomníky (Monuments and Memory Lost). Prague, Litomyšl: Paseka 1997; Roman Prahl, Výtvarné umění v divadle (Visual art in the theatre). In: Zdeňka Benešová et al. (eds), Národní divadlo – historie a současnost budovy. History and Present Day of the Building. Geschichte und Gegenwart des Hauses, Prague: Národní divadlo 1999, pp. 107–125.

32 Franz Kafka to Oskar Pollak, 20 December 1902. Franz Kafka, Letters to Friends, Family, and Editors. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston from the German original. New York: Schocken Books 1977, p. 5 f.

33 Note especially the word ‘claws’ (‘Krallen’) in this letter and in the later story ‘The silence of the Sirens’. – See also Michel Reffet, Franz Kafka und der Mythos (Franz Kafka and Myth). In: brücken. Germanistisches Jahrbuch Tschechien – Slowakei. NF 9–10 (2003), pp. 155–168.

34 See Marek Nekula, Constructing Slavonic Prague: The ‘Green Mountain Manuscript’ and public space in discourse. Bohemia 52 (2012), pp. 22–36.

35 See Brod – Kafka, Eine Freundschaft, p. 401; Nekula, Die deutsche Walhalla und der tschechische Slavín.

36 Translation from the Czech original. See Franz Kafka to Růžena Hejná (Wettenglová), 1 October 1917. – See Kafka, Briefe April 1914–1917 (Letters April 1914–1917). Ed. by Hans-Gerd Koch. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer 2005, p. 341.

37 Franz Kafka to Max Brod, 30 July 1922. – See Kafka, Letters to Friends, Family, and Editors, p. 347.

38 In a speech given at the inauguration of the monument to Palacký, Karel Kramář, a prominent Czech politician of the day, called for equality of Czechs and Germans in Bohemia and legal autonomy for Bohemia. See also Hojda – Pokorný, Pomníky a zapomníky, p. 102. ‘Sokol’ is a sports association. In the 19th century it was a mass organization for nationalistic Czechs with some cultural goals (books, periodicals, public readings, etc.). It was also noticeably paramilitary in character, at least in the 19th century.

39 See Marek Nekula, Prager Brücken und der nationale Diskurs in Böhmen (Prague bridges and the national discourse in Bohemia). In: brücken. Germanistisches Jahrbuch Tschechien – Slowakei. NF 12 (2004), pp. 163–186. ‘German’ professors commissioned a statue of the Emperor Charles IV on the bridgehead of the Charles Bridge in 1848 and thus gave Charles IV a role in the national discourse of the 19th century.

40 See Nelly Engel, Franz Kafka als ‘boyfriend’ (Franz Kafka as a boyfriend). In: Hans-Gerd Koch (ed.), „Als Kafka mir entgegen kam. . .“: Erinnerungen an Franz Kafka (‘As Kafka approached me’. Recollections of Franz Kafka). Berlin: Wagenbach 1995, pp. 118–124.

41 Franz Kafka, Letters to Milena. Translated and with an introduction by Philip Boehm. New York: Schocken Books 1990, p. 16.

42 See Binder, Kafka-Handbuch in zwei Bänden.

43 See Kafka, Ein Landarzt, p. 52. – Kafka, Stories 1904–1924, p. 56. See also Kafka, The Complete Short Stories, p. 88.

44 See Kafka, Ein Landarzt, p. 39. – See also Kafka, Stories 1904–1924, p. 45.

45 Kafka, Letters to Milena, p. 212.

46 Kafka, The Complete Short Stories, p. 326 f.