INTRODUCTION

SOVEREIGN-RISK ANALYSIS has acquired a new importance as more and more emerging-market governments borrow in the international capital markets. Governments borrow for a number of reasons, most importantly to finance their fiscal and current-account deficits. In addition to borrowing from banks, governments borrow from the public by issuing bonds, both in domestic and foreign currency. A bond (or debt instrument) is simply an IOU that describes the terms of the contract between borrower and lender, including the cost of borrowing and the promise of repayment in full by a certain time. Sovereign risk refers to the risk that the government will not service its debt in full and on time.

While corporate rate issuers often need to pledge some asset as collateral, a government borrows based on its capacity to raise taxes and adopt other monetary and exchange-rate policies to cover its debt. Hence sovereign-risk analysis focuses on the ability, flexibility, and willingness that the government has to take appropriate policy measures to facilitate its debt servicing.

Investors purchase government bonds according to their appetite for risk. Those who are risk averse will be likely to purchase U.S. Treasury Bills, the returns on which are low because of their low risk. Those who are risk prone are more likely to be attracted to emerging-market bonds where the higher return is commensurate to the higher risk.

Investor funding is often pooled together and managed by a professional money or fund manager. These institutional investors, including pension and mutual funds, are active in government bond markets and are often subject to stringent regulations in terms of the bonds they can purchase. In some cases, for example, they require that the bonds have “investment grade” ratings by at least two of the international rating agencies, that is, until recently, Moody’s Investors Service (Moody’s), Standard & Poor’s (S&P) and Fitch Ratings (Fitch).1

In making their investment decisions, investors rely on sovereign-risk analysis, including that of the rating agencies, the International Monetary Fund, and the investment banks. To evaluate risk, analysts need to place economic and financial issues in the context of the political, institutional, and social conditions in the country. Such evaluation depends critically on the data and methodology used as well as on the competence, training, and experience of the analysts. Seasoned analysts are necessary not only to interpret basic economic and financial indicators but also to assess policy flexibility and policy consistency. Policy flexibility is necessary for the government to react quickly and boldly to external and internal shocks.2 Policy consistency refers to the need to have fiscal, monetary, and exchange-rate policies that reinforce one another rather than clashing.3 Policy inconsistencies and the inability of governments to react quickly to shocks through policy changes are often the main cause of crises.

THE ACTORS

Different actors analyze sovereign risk differently. Although this chapter focuses on rating agencies, we shall briefly discuss the ways other actors analyze sovereign risk.

THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Although the IMF does not rate governments as such, sovereign-risk analysis is part of its macroeconomic surveillance functions. Surveillance, known as Article IV consultations, involves monitoring and consultations with member states on a wide range of economic and financial policies. For surveillance purposes, member states provide the IMF with all necessary information. Particularly in the wake of the Mexican financial crisis of 1994–95 and the turmoil in the financial markets of East Asia in 1997, data issues have received increasing prominence in the IMF’s work. In aiming to strengthen surveillance, the IMF requires the provision of comprehensive, timely, and accurate economic data by members.

To implement its surveillance functions on a country, the IMF focuses on the accounting, analysis, and projections of each of the four interconnected sectors in the economy: the national income account (or the real sector), the balance of payments (or the external sector), the fiscal sector (or the government finance statistics), and the monetary sector. The links between the income and spending balance of a sector (or its saving-investment balance) and the associated financial transactions with other sectors are systematically described in a “flow of funds” account. A flow of funds analysis among the four sectors is carried out to ensure that projections for the different sectors are feasible and that inconsistencies do not arise. For example, if a rate of growth of 3 percent is projected for an economy, the flow of funds among the sectors will show whether the financing for the projected investment is available, either from the domestic financial sector or from abroad. Also, the flow of funds analysis would show whether the projected rate of growth is compatible with the current-account deficit that the country can expect to finance through foreign borrowing, portfolio and foreign direct investment, and international reserves, and whether it is compatible with projections for the fiscal accounts and domestic inflation.

Thus, IMF methodology ensures the consistency of available data and projections, helps to identify policy inconsistencies rigorously and facilitates macroeconomic and risk analysis. This framework is also useful in policy simulations, which is a form of forecasting that generates a range of alternative projections based on differing assumptions about future situations, specifically to answer the question “what would happen if?” In the financial programming exercise of a middle-sized country, six to ten Ph.D.’s and other well-qualified and experienced economists participate,4 mostly from the area department, but often involving experts from fiscal, monetary and exchange, and other departments.

While emphasis is put on policy consistency, IMF sovereign-risk analysis often exaggerates policy flexibility due to the frequent inability of macroeconomists to incorporate political constraints into policymaking. This has often led them to underestimate sovereign risk. The recent case of Uruguay, which required a huge IMF program in terms of the country’s GDP in 2002, is a case in point.5 The IMF greatly overestimated the government’s political flexibility in dealing with the fiscal problems and structural reforms necessary to stave off contagion from Argentina and Brazil.

INVESTMENT BANKS

Although investment banks also analyze sovereign risk, they do not rate governments. Furthermore, to facilitate investors’ decisions in general, these banks focus on short-term sovereign-risk analysis rather than on more medium- and long-term perspectives. In some cases, their tools to assess sovereign risks include financial programming to evaluate macroeconomic consistency. Some of the large investment banks provide excellent publications (often on a daily basis) on sovereign-risk analysis that are widely used by investors. Investment banks employ many M.B.A.’s and some Ph.D. economists, often with IMF backgrounds. Research from investment banks, however, has been criticized because of its lack of independence from the investment-banking functions of these banks.

RATING AGENCIES

Unlike the IMF and investment banks, rating agencies translate their sovereign-risk analysis into a sovereign rating of either the government debt or specific government issues. Sovereign ratings represent just one opinion of government creditworthiness, and the impact they ultimately have on the markets depends on how investors make use of the ratings themselves, on their timeliness, and on the soundness of the economic and political explanations given to justify them. Sovereign ratings facilitate cross-country comparisons of governments’ creditworthiness. In analyzing risk, rating agencies rely to a large degree on basic economic and financial indicators and a qualitative analysis of policy flexibility and political developments. There are institutional and economic reasons for which governments seek ratings—often from two or three different agencies—and pay for them. Ratings determine the terms and conditions of access to global securities markets. For regulatory reasons, ratings often allow governments to attract a larger investor group and establish risk benchmarks.6

For ratings agencies, sovereign ratings are an assessment of a government’s ability and “willingness” to service its debts “in full” and “on time.” They view the rating as a forward-looking estimate of the probability of government default.7 As such, sovereign ratings will determine the cost of government borrowing, are a basis for the ratings of corporations, banks, local governments, and other entities in the country, and are important in the determination of country risk. Sovereign ratings normally also impose a ceiling to the ratings of government-supported institutions such as state-owned enterprises.8

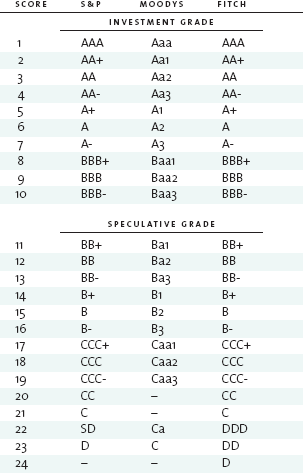

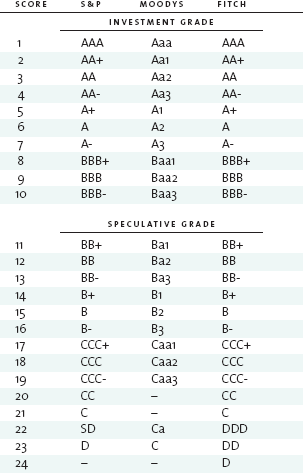

Ratings agencies use letter-based grading systems and base their ratings on peer comparisons.9 The rating scale applies equally to all classes of obligors, sovereign as well as subsovereigns. Ratings agencies assign long-term and short-term sovereign credit ratings as well as foreign and local currency sovereign ratings. An “outlook” is assigned to the long-term ratings (positive, stable, or negative). Local currency ratings often surpass the foreign currency ratings, reflecting the ability of governments to tax and borrow from the domestic economy on a sustainable basis.10 In assigning long-term ratings, the agencies indicate that they try to see through economic, political, credit, and commodity cycles. This means that a domestic recession or deteriorating conditions in the global economy by itself should not be an occasion for a downgrade. Rating agencies review their ratings at specific times when particular events may have had an impact on the rating or, lacking such events, on a yearly basis.

Rating agencies’ concept of default is not based on a legal definition. Agencies consider that a default takes place when debtors fail to meet a principal or interest payment on the due date or a distressed or coercive rescheduling of principal and/or interest takes place on terms less favorable than those originally contracted. In practice, however, a generalized sovereign default (default on all outstanding debts) is rare. Normally, defaults are selective and sequenced, reflecting the de facto if not de jure seniority of different types of debt instruments. S&P’s SD (selective default) rating applies only to issuers but not to specific debt instruments. When a specific debt instrument is in default the rating is D.

TABLE 12.1

RATING SCALE

Source: Bhatia, “Sovereign Credit Ratings Methodology,” 8.

DETERMINING FACTORS

In analyzing sovereign risk, rating agencies do not in general use specific models.11 Instead, they generally focus on a number of quantitative and qualitative factors that affect sovereign default risk. The reason why they do this is that the variables that affect sovereign risk are highly interrelated (and correlated), and hence it is difficult to isolate their individual effects through econometric work.

Despite the difficulties, some empirical studies tried nevertheless to identify which factors had historically received the greatest weights in the ratings process of Moody’s and S&P’s. Canton and Packer’s research identified high per capita income, low inflation, more rapid growth, a low ratio of foreign-currency external debt to foreign-exchange earnings, the absence of a history of defaults, and a high level of economic development as factors associated with high ratings.12 Despite the high predictive power of the model,13 factors such as the fiscal position and the external balance were not identified as determinants of the ratings. This, of course, can be explained by the high correlation among these variables.

In the late 1990s, econometric work was revised to take into account new variables that were affecting sovereign ratings. Juttner and McCarthy found that the variables identified by Canton and Packer continued to explain ratings up to 1997 but that the relationship broke down in 1998 in the wake of the Asian crisis.14 In 1998, additional variables, such as the ratio of problematic bank assets to GDP and the interest-rate differential (a proxy for expected exchange rate changes), came into play.

The factors used in risk analysis are disaggregated in a number of broad categories. They include:

Political factors, including the level of democratization, the degree of plurality, the division of powers, the orderly transition of heads of government and other officials, freedom of the press, the support for policy making, the strength of institutions, public security, and geopolitical considerations are critical to sovereign ratings.

Political factors, including the level of democratization, the degree of plurality, the division of powers, the orderly transition of heads of government and other officials, freedom of the press, the support for policy making, the strength of institutions, public security, and geopolitical considerations are critical to sovereign ratings. The economic structure and growth prospects of an economy are key considerations in analyzing sovereign ratings. The indicators used for this purpose include measures for income (GDP, per capita GDP, and real GDP growth and its components); savings and investment levels in relation to GDP; open unemployment; prices (CPI, WPI, GDP deflator); and exchange rates (flexible vs. fixed; real exchange rate as a measure of international competitiveness). Other factors that are more difficult to quantify are also taken into account, such as the diversification of the economy, the level of economic development and income distribution in the country, labor market flexibility, the efficiency of the public sector, and the degree of financial sector intermediation.

The economic structure and growth prospects of an economy are key considerations in analyzing sovereign ratings. The indicators used for this purpose include measures for income (GDP, per capita GDP, and real GDP growth and its components); savings and investment levels in relation to GDP; open unemployment; prices (CPI, WPI, GDP deflator); and exchange rates (flexible vs. fixed; real exchange rate as a measure of international competitiveness). Other factors that are more difficult to quantify are also taken into account, such as the diversification of the economy, the level of economic development and income distribution in the country, labor market flexibility, the efficiency of the public sector, and the degree of financial sector intermediation. Fiscal flexibility is another major determinant of sovereign ratings. This includes not only an analysis of fiscal flows (revenue, expenditure, balance) but also of stocks (debt levels, debt burden) and off-budget and contingent liabilities (unreported and contingent claims on government resources such as, for example, those resulting from the up-front fiscal costs of banking-system collapses). The fiscal situation of different levels of government—that is, the central government, the general government (central government plus local governments), and the consolidated public sector (general government plus state-owned enterprises)—is often analyzed separately.

Fiscal flexibility is another major determinant of sovereign ratings. This includes not only an analysis of fiscal flows (revenue, expenditure, balance) but also of stocks (debt levels, debt burden) and off-budget and contingent liabilities (unreported and contingent claims on government resources such as, for example, those resulting from the up-front fiscal costs of banking-system collapses). The fiscal situation of different levels of government—that is, the central government, the general government (central government plus local governments), and the consolidated public sector (general government plus state-owned enterprises)—is often analyzed separately.Fiscal indicators used by rating agencies for the public sector include revenues vs. expenditures; primary balance; consolidated public-sector balance (i.e., public sector borrowing requirements, or PSBR, which is a measure of increased indebtedness, the degree of the public sector’s crowding out the private sector, and inflationary pressure). Other indicators include the stock of public sector assets and liabilities (on a gross and net basis) and a number of critical ratios. These include: interest payments in relation to total revenue; oil revenue as a proportion of total revenue; and net public sector debt in relation to GDP. The maturity profile and the currency composition of the debt as well as the development of local capital markets are important determinants of fiscal flexibility.

Monetary and liquidity factors are used to analyze inflationary conditions and exchange-rate sustainability. Indicators used include domestic credit to the private sector, monetary aggregates (including M1, M2, and so on) in relation to international reserves, short-term interest rates, core and nominal inflation, and a liquidity ratio (external liabilities of banks vs. external assets). The health of the banking system is measured by the degree of nonperforming loans and capital adequacy. Consistency between exchange rate and monetary/credit policies and institutional factors such as central bank independence are also taken into account.

Monetary and liquidity factors are used to analyze inflationary conditions and exchange-rate sustainability. Indicators used include domestic credit to the private sector, monetary aggregates (including M1, M2, and so on) in relation to international reserves, short-term interest rates, core and nominal inflation, and a liquidity ratio (external liabilities of banks vs. external assets). The health of the banking system is measured by the degree of nonperforming loans and capital adequacy. Consistency between exchange rate and monetary/credit policies and institutional factors such as central bank independence are also taken into account. External payments and debt is the category used to ascertain the adequacy of international reserves and the availability of foreign-exchange earnings that the country has in order to service its liabilities. This category is used to analyze both balance of payments flows and the stock of international debt. Indicators used include BOP data: trade balance (exports, imports, balance); current account (trade balance; factor payments, including interest and dividends; transfers); capital and financial account (net foreign direct investment and net borrowing). The composition of the current and capital and financial accounts are taken into consideration, as is the adequacy of international reserves and access to international capital markets. Important ratios in this category include the share of the current account deficit covered by foreign direct investment and the months of imports covered by international reserves.

External payments and debt is the category used to ascertain the adequacy of international reserves and the availability of foreign-exchange earnings that the country has in order to service its liabilities. This category is used to analyze both balance of payments flows and the stock of international debt. Indicators used include BOP data: trade balance (exports, imports, balance); current account (trade balance; factor payments, including interest and dividends; transfers); capital and financial account (net foreign direct investment and net borrowing). The composition of the current and capital and financial accounts are taken into consideration, as is the adequacy of international reserves and access to international capital markets. Important ratios in this category include the share of the current account deficit covered by foreign direct investment and the months of imports covered by international reserves.Indicators for the stock of debt include total external debt, public and private, short-term and long-term, and net external debt. To calculate net levels of debt, international reserves, government deposits at the central bank, and other public and private assets are taken into account. An indicator for debt burden is total debt service (amortization and interest). Critical ratios in this category include total and net external debt in relation to foreign exchange earnings, the proportion of short-term debt covered by international reserves, and the proportion of the gross financial gap (current account deficit plus amortization payments plus short-term debt) covered by international reserves.

Until recently, only three rating agencies were “nationally recognized statistical rating organizations” or NRSROs.15 This gives these agencies a virtual oligopoly. In addition to the sovereigns, many corporations, as well as state and local governments, require ratings by these institutions. Institutional investors often require “investment grade” ratings from Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s (thus creating a de facto duopoly) and putting these two agencies in a preferential position vis-à-vis Fitch.16

CRITICISM OF RATING AGENCIES

Because of the power of the rating agencies to determine the cost, terms, and conditions of access to global securities markets, the agencies have had a major impact on the large capital flows to emerging markets in the 1990s. At the same time, their inability to detect financial failures in Asia brought severe criticism of the ratings agencies’ role in the evaluation of sovereign credit risk. Critics have argued that agencies gave too little warning before the onset of the Asian crisis and overreacted once the crisis emerged.17 The same kind of criticism was made on subsequent crises, most recently in the cases of Uruguay and the Dominican Republic.

Since the Asian crisis, criticisms of rating agencies have been grouped into three areas: the ratings themselves and the impact they have on capital flows; the oligopolistic nature of their business and the lack of incentive for good performance; and the way the agencies finance themselves. The latter creates not only a conflict of interest but has also resulted in the inadequacy of resources devoted to establishing the ratings. The three, however, are interlinked in many ways.

PROCYCLICAL IMPACT ON CAPITAL FLOWS

Given the sharp adjustments to sovereign credit ratings in Asia in the period starting in August 1997 and as recently as last year in the case of Uruguay, sovereign ratings have often been responsible for introducing a procyclical bias into global capital flows. This means that as the country is doing badly, ratings collapse, and, as they do, capital outflows accelerate markedly.

Some analysts argue that downgrades are often late and that they follow the market rather than leading it.18 For example, S&P rated Thailand A (stable) until August 1997,19 well after the July devaluation. Korea’s rating of AA minus (stable) was maintained until August 1997, and in five months it was downgraded nine notches to B plus (credit watch negative) in December of that year.20 Russia was downgraded to B plus (stable) in June 1998 and put on selective default in January 1999. Brazil was downgraded to B plus (negative) only the day before the 15 January 1999 devaluation, when the crisis had been brewing for some time.21

Many analysts feel that downgrades for Argentina and Turkey from 2000 through 2002 have mostly followed the market as well. Uruguay was kept at investment grade by the three major ratings agencies until February 2002, four months before the peak of the banking crisis; these agencies ignored contagion factors from Argentina and Brazil, the lack of fiscal flexibility, and the inability of the government to adopt structural reforms that could have made the country less vulnerable to external shocks. Then the rating was brought down by six notches in less than nine months and was put in SD six months later.22 The Dominican Republic was rated BB minus (stable) until 15 May, when the outlook was changed to credit-watch negative. On 9 June the country’s rating was downgraded to B plus (negative), and its outlook changed to negative (from stable) in the last days of June 2003 on concerns that the nation’s heavy depreciation and banking-sector stress would undermine its medium-term economic outlook and make external payments difficult. These rating and outlook changes came only after the mid-May collapse of the Banco Intercontinental (Baninter).

As Helmut Reisen pointed out,

If sovereign ratings lag rather than lead the financial markets but have a market impact, improving ratings would have euphoric expectations and stimulate excessive capital inflows during the boom; during the bust, downgrading might add to panic among investors, driving money out of the country and sovereign yield spreads up. For example, the downgrading of Asian sovereign ratings to “junk status” reinforced the region’s crisis in many ways; commercial banks could no longer issue international letters of credit for local exporters and importers; institutional investors had to offload Asian assets as they were required to maintain portfolios only in investment grade securities; foreign creditors were entitled to call in loans upon the downgrades.23

The more recent experience in Uruguay is similar in many ways, although the visible signs of contagion and lack of progress on structural reform had been more obvious for quite some time.

OLIGOPOLISTIC NATURE

At the same time that the rating agencies were under attack throughout the world as a result of their sovereign ratings, the Securities and Exchange Commission pledged in January 2003 a “sweeping overhaul of the regulation of credit rating agencies” following criticism of their role in the collapse of Enron and the crisis in the telecommunications industry.24 The ratings agencies were accused of being too slow in the case of Enron, keeping its rating at investment grade until just four days before it filed for bankruptcy on 2 December 2001. On the other hand, a noncertified rating agency, Egan-Jones Rating Co., which sells ratings to investors, downgraded Enron to junk a month before the big agencies.25 In the case of the telecoms, the agencies were accused of cutting ratings too hastily and precipitating the crisis in their sector.26

Lawrence White of New York University argues that the protective regulations responsible for the oligopolistic nature of ratings agencies have “lured these agencies into complacency.” He recommends two ways to revert this process. First, the SEC and other regulators could require that financial institutions defend their judgments about their bond holdings instead of providing the market with a list of approved rating agencies. Then the SEC could eliminate its certification process and allow other rating agencies to get into the ratings business. Second, if regulators are not prepared to do this, then the SEC should certify new rating agencies that can demonstrate competence and expertise in predicting bond defaults. In White’s view “one way or the other, the creation of some fresh competition to challenge the Big Three is essential.”27 He also argued that “the NRSRO status is simply a way of coddling the three agencies and stifling competition in what should be an industry as competitive as any other.”28 Sir Howard Davies, chairman of the UK’s Financial Services Authority, said at the World Economic Forum in Davos that certification should be lifted and that the participants in the credit rating business should “stand on their own feet.”29 Senator Joseph Lieberman has pointed out that tougher regulation of the ratings industry may be needed. In his view, “power of this magnitude should go hand in hand with some accountability.”30

A study by Richard Johnson of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City concluded that one reason why the rating agencies are reluctant to cut a company’s creditworthiness to junk status is because of the severe consequences that usually result—often leading to a rapid default and heavy losses for the investors. Furthermore, much corporate debt is sold with “triggers,” whereby a downgrading of a company’s credit rating can accelerate the repayments schedule.31

CONFLICT OF INTEREST AND INADEQUACY OF RESOURCES

In February 2003, the G7, led by France, reported the need to agree to a set of principles to make rating agencies more transparent and accountable, both in their corporate and sovereign ratings. French officials want the G7 to recognize that the rating agencies are “privately-run, profit-oriented businesses that also run the risk of conflict of interest.”32 It is still to be seen whether such recognition would pave the way for changes to make these agencies more competitive and hence more transparent and accountable.

Some analysts have also raised the issue of conflict of interest. Former S&P analyst Ashok Bhatia noted that “each agency’s sovereign ratings group remains excessively reliant on issuer-fee revenue, creating incentives for ratings generosity; and ongoing diversification into parallel consultancy business may be exacerbating conflicts of interest, strengthening incentives for ratings generosity.” Furthermore, he pointed out that “each agency’s sovereign ratings group faces an asymmetry in its revenue structure, with reliance on fee income from issuers creating incentives in favor of ratings generosity. This bias is especially acute in the case of new ratings, because ratings agreements typically allow previously unrated issuers to suppress their ratings, if they so prefer, and because interagency competition tends to be focused on attracting new ratings clients.”33

The IMF also seems to be concerned about the conflict of interest affecting member states. In addition to concerns expressed in 1999,34 on 27 March 2003, the head of the IMF’s Capital Markets Department, Gerd Haeusler, announced in Frankfurt that the IMF planned to take a close look at the way international credit rating agencies work, “most importantly in the context of potential conflicts of interest, given the fact they are paid by those whom they rate.” Mr. Haeusler questioned whether there is enough competition and enough expertise to look at corporations and countries in various parts of the world.35

The potential conflict of interest was also an issue in the House of Representatives hearing on 3 April 2003, as was the issue of regulation and competence of the rating agencies. The rating agencies remain basically unregulated despite determining borrowers’ access to the debt markets and how much companies and countries have to pay to borrow. They are subject to no federal reporting requirements, and there are no written rules about the training and hiring of their employees. From this some witnesses concluded that the system is flawed and in need of reform.36

On 15 January 2004, Charles Dallara, managing director of the Institute of International Finance, said that “it is important for investors not to rely too heavily on the ratings agencies, but to make their own assessments of sovereign risk to differentiate between countries and classes of assets.” He noted that bond spreads, or the risk premium that foreign governments and companies must pay over U.S. rates, had fallen sharply over the previous year. He argued that this was true even for countries such as Peru, the Philippines, Poland, and Venezuela, where credit quality had deteriorated.37 The adequacy of resources of rating agencies is also questioned by Bhatia, who noted that “as profit-seeking entities, all three major ratings agencies strive to maintain streamlined operations, resulting in considerable rationing of analytical man-hours.” He reckons that on average, analysts at S&P cover about five sovereign credits.38

Recent job announcements hint that the burden might be even more overwhelming. S&P job announcements for analysts in the Wall Street Journal (30 April 2002) and in The Economist (25 May 2002) state that, in addition to covering sovereign credits, the analysts should cover sovereign-supported issuers (state-owned enterprises including state development banks) and at times supranational issuers (including regional and international banks). This requirement overlooks the fact that to analyze risk relating to these institutions requires a different set of capabilities and expertise than for analyzing sovereign risk.39 Furthermore, academic requirements and years of experience required seem hardly commensurate to the overwhelming task. For a sovereign analyst, graduate training in economics and only two years of experience are required. For a director of sovereign ratings—covering both Latin America and Asia—S&P requires a “master’s degree in economics or international public affairs and three years in position offered [sic].” This contrasts sharply with requirements at the IMF where entry-level economists normally have Ph.D.’s from reputable universities, and many years of experience are required for more senior positions.

The number and diversity of credits, the limited academic training for conducting rigorous analysis, and the short work experience required are all factors reflected in the poor performance of sovereign ratings. In Bhatia’s view,

The heavy workload at the ratings agencies may result in an element of piggybacking, with analysts relying to varying degrees on research produced by the IMF, academia, investment banks, and—conceivably—other rating agencies as they seek to remain abreast of developments.40 To the extent that analysis free-rides on the IMF or other entities, the agencies dilute their own contribution and so run the risk of simply joining the prevailing consensus. To the extent that analysis free-rides on market participants and their affiliates, the agencies compromise their objectivity. The relatively small action by an individual analyst of tabling selected investment bank “sell-side” or “buy-side” research literature in a ratings committee can trigger a string of errors culminating in rating failure. Despite ongoing efforts by the agencies to increase their analytical resource bases and introduce greater specificity into their ratings methodologies, it may be argued that ratings failures such as that for Uruguay in 2002 were the result of inattention, with insufficient resources devoted to data gathering, corroboration, and analysis.41

Because of the devastating impact that bad or untimely sovereign ratings can have on both countries and investors, the regulatory framework needs to be changed to ensure that sovereign ratings are done competitively by qualified analysts with the expertise and resources necessary to analyze the consistency and sustainability of macroeconomic policies in the framework of the political and institutional conditions of each country. In fact, governments paying for the ratings should demand that this be so.

TIPS FOR REPORTERS

Reporters need to find out who are the rating agencies analysts for the country in question and try to get to know them. Contact should be made with analysts from the investment banks and with the IMF External Relations Department and other relevant staff.

Reporters need to find out who are the rating agencies analysts for the country in question and try to get to know them. Contact should be made with analysts from the investment banks and with the IMF External Relations Department and other relevant staff. What are the key issues that the rating agencies/IMF/investment banks are looking at?

What are the key issues that the rating agencies/IMF/investment banks are looking at? Reporters should send relevant published stories on the countries covered to the rating agencies/IMF/investment banks to establish credentials as a knowledgeable source. This could help develop a mutually beneficial relationship.

Reporters should send relevant published stories on the countries covered to the rating agencies/IMF/investment banks to establish credentials as a knowledgeable source. This could help develop a mutually beneficial relationship. Reporters should exploit the pressure analysts feel to be “in the news.”

Reporters should exploit the pressure analysts feel to be “in the news.” Who, where, and what are the sources of information for these analysts, and how reliable are they?

Who, where, and what are the sources of information for these analysts, and how reliable are they? What other sources of information are there that may have been overlooked or to which reporters have easier access?

What other sources of information are there that may have been overlooked or to which reporters have easier access? Reporters should beware of methodological differences that may lead to differences in results.

Reporters should beware of methodological differences that may lead to differences in results. Reporters should beware of a herd instinct by ratings agencies as a result of having the same sources of information and pressure from the markets.

Reporters should beware of a herd instinct by ratings agencies as a result of having the same sources of information and pressure from the markets. The records of analysts on particular topics should be examined closely. Reporters should return to the issues six or twelve months later to see whether the analysts proved to be correct.

The records of analysts on particular topics should be examined closely. Reporters should return to the issues six or twelve months later to see whether the analysts proved to be correct. Analyses should be focused on some of the issues discussed here with the purpose of creating debate and improving the ratings.

Analyses should be focused on some of the issues discussed here with the purpose of creating debate and improving the ratings.LINKS FOR MORE INFORMATION

6. IDEAS, an electronic database maintained by the University of Connecticut, carries many research reports and working papers on the issue of sovereign risk. http://ideas.repec.org.

7. The Emerging Markets Companion, Inc. site, run by the research firm with the same name, carries commentaries, news analyses, and research reports on emerging markets. http://www.emgmkts.com.

NOTES

1. Fitch is the product of the merger of Fitch IBCA and Duff & Phelps Credit Rating Co. in March 2000. This allowed them to become a strong competitor to Moody’s and S&P.

2. For example, if, as a result of a shock, the government needs to cut the fiscal deficit, can it raise taxes or cut expenditure easily, or would it face difficulties (political and others)? If wages and pensions represent a large share of total expenditure, the flexibility to cut expenditure will be low. If taxes are already high, flexibility to raise them will be limited. A major determinant of policy flexibility is the political support the government has in congress and how easily it can pass major policy reforms.

3. For example, the Mexican crisis of 1994 was clearly caused by incompatible exchange-rate and monetary policies. While the exchange rate was fixed, the government reacted to the fall in reserves due to an exogenous shock by increasing the money supply over and above what was compatible with the maintenance of the fixed exchange rate. Similarly, the collapse of fixed exchange rates in the Southern Cone countries in Latin America in the early 1980s was the result of inconsistencies between the fixed-exchange-rate system and the need to monetize (finance through money creation) large fiscal deficits.

4. The IMF recruits Ph.D. economists from top universities in the United States and abroad as well as senior government officials from central banks and ministries of finance. Since the Asian crisis, the IMF has also recruited economists with experience in the markets. At the same time, the IMF Institute provides constant training not only to incoming staff but also to senior and middle-level staff on a large number of issues. In this way, the IMF constantly updates and upgrades the capacity of its staff to carry out macroeconomic and risk analysis.

5. The Uruguayan program of close to $3 billion represented about 23 percent of that country’s GDP. In comparison, the much-publicized Brazilian program of $30 billion represented only 5 percent of GDP.

6. The policies of these agencies are not homogenous. For example, contrary to Moody’s, S&P only rates countries at their request, and the ratings are made public only after the country has agreed. Hence, S&P is always paid for its ratings, while Moody’s has rated countries without the request of the countries and without payments.

7. Thus, sovereign ratings are not “country ratings.”

8. Sovereign ratings normally cap other ratings because the government could impose foreign-exchange or capital controls or any other constraint that could make nongovernmental entities default on their debts.

9. This creates the obvious problem that peer ratings have to be current at the time of the comparison for the comparison to be meaningful. Given that ratings are often revised on a yearly basis, this might not always be the case.

11. See IMF, International Capital Markets 1999 (Washington, D.C.: IMF, 24 September 1999). See chapter 5, “Emerging Markets: Nonstandard Responses to External Pressure and the Role of the Major Credit Rating Agencies in Financial Markets,” available at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/icm/1999/pdf/file05.pdf; and annex 5, “Credit Rating and the Recent Crises,” available at www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/icm/1999/pdf/file11.pdf. The study also argues that up to that time, rating agencies did not generally conduct extensive scenario analyses and stress testing, and they only rarely assigned probabilities to specific risk factors and scenarios. From recent reports and methodological notes, it does not seem that these trends have changed much.

12. R. Cantor, and F. Packer, “Determinants and Impact of Sovereign Credit Ratings,” Economic Policy Review 20, no. 2 (1996): 37–53.

13. This means that the variables mentioned explain a large percentage of the variation in sovereign ratings.

14. J. D. Juttner and J. McCarthy, “Modeling a Ratings Crisis,” unpublished paper, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia, 1998.

15. A Financial Times editorial, “The Ratings Business” (10 February 2003) notes that “this arbitrary designation was introduced by the SEC in 1975, long after S&P and Moody’s were founded and at a time when the business was more competitive. Since then the field has been cut to the Big Three by the series of mergers that created Fitch” and argues for the need to eliminate what “increasingly looks like a cartel.”

16. In February 2003, the SEC added a fourth agency to the list, Dominion Bond Rating Service Ltd., a small Canadian firm that had been seeking status for more than three years.

17. See IMF, International Capital Markets 1999; Helmut Reisen, “Ratings Since the Asian Crisis,” ICRA Bulletin 2, no. 8 (January–March 2002): 14–35; H. Reisen and J. von Maltzan, “Boom and Bust and Sovereign Ratings,” Technical Paper No. 148 (Paris: OECD Development Centre), www.oecd.org/dev/dataoecd/38/44/1922795.pdf, and Carment Reinhart, “Default, Currency Crises, and Sovereign Credit Ratings,” in The World Bank Economic Review 16 (2000): 151–70; and Ratings, Rating Agencies, and the Global Financial System, ed. R. M. Levich, G. Majnoni, and C. Reinhart (New York: Kluwer Academic Press, 2002).

18. For evidence of causality between sovereign ratings and market spreads, see G. Larrain, H. Reisen, and J. von Maltzan, “Emerging Market Risk and Sovereign Credit Ratings,” Technical Paper No. 124 (Paris: OECD Development Center, 1997); Helmut Reisen, “Ratings Since the Asian Crisis”; and Carment Reinhart, “Default, Currency Crises, and Sovereign Credit Ratings.”

19. Ratings throughout the chapter refer to foreign-currency sovereign ratings.

20. See Japan Center for International Finance (JCIF), “Characteristics and Appraisals of Major Rating Agencies,” 2000, available at www.jcif.or.jp/e-index.htm; and JCIF, “Characteristics and Appraisals of Major Rating Companies,” 1999, available at www.jcif.or.jp/e_index.htm. In the case of Korea, JCIF found a strong correlation between S&P and Fitch ratings changes and market fluctuations. It also noted that the S&P also changed ratings of other countries extremely frequently, as in the case of Indonesia (eight times) and Malaysia (five times).

21. JCIF, “Characteristics and Appraisals of Major Rating Companies,” 2000; JCIF, “Characteristics and Appraisals of Major Rating Companies,” 1999. JCIF noted differences in the way rating agencies interpreted events and the timing of ratings revisions based on those interpretations. Thus, some downgrades were timelier than others. For example, Moody’s downgraded Thailand in April 1997 before the plunge in the baht. Also, while Duff & Phelps and Moody’s downgraded Brazil right after the Russian crisis, showing foresight in incorporating contagion from the crisis into the ratings, Fitch IBCA and S&P did not.

22. After a debt exchange was completed, S&P updated Uruguay’s rating to B minus on 2 June 2003 (from the SD rating imposed on 16 May).

23. Helmut Reisen, “Ratings Since the Asian Crisis,” 21–22.

24. J. Wiggins, V. Boland, and C. Pretzlik, “SEC Pledges Overhaul of Credit Rating Agencies,” Financial Times, 25–26 January 2003.

25. Amy Borrus, “The Credit-Raters: How They Work and How They Might Work Better,” Business Week, 8 April 2002.

26. Financial Times, editorial, “The Ratings Business,” 10 February 2003.

27. Lawrence White, “Credit and Credibility,” New York Times, 24 February 2002.

28. Vincent Boland, “Rating Agencies May Lose Status,” Financial Times, 3 April 2003.

29. Wiggins, Boland, and Pretzlik, “SEC Pledges Overhaul.”

30. Borrus, “The Credit-Raters.”

31. Vincent Boland, “Rating Agencies May Lose Status.”

32. R. Graham, J. Wiggins, and A. van Duyn, “Credit Rating Agencies to Be G7 Issue,” Financial Times, 5 February 2003.

33. Bhatia, “Sovereign Credit Ratings Methodology,” 51 and 45.

34. IMF, International Capital Markets 1999.

35. Newsmachine, “IMF Wants to Take Close Look at Work of Credit Rating Agencies,” AFP, 27 March 2003.

36. Alec Klein, “Lawmakers Criticize SEC’s Oversight of Credit-Rating Firms,” Washington Post, 3 April 2003.

37. Dow Jones International News, 15 January 2004.

38. Bhatia, “Sovereign Credit Ratings Methodology,” 44.

39. Macroeconomics accounting, that is, the accounting of the real, monetary, fiscal, and external sector, which is critical for macroeconomic analysis and projections is quite different from corporate accounting. In fact, they normally are not only taught in different university courses but at different schools within the university.

40. Sovereign ratings by the three major rating agencies rarely differ by more than two notches.

41. Bhatia, “Sovereign Credit Ratings Methodology,” 45.

Political factors, including the level of democratization, the degree of plurality, the division of powers, the orderly transition of heads of government and other officials, freedom of the press, the support for policy making, the strength of institutions, public security, and geopolitical considerations are critical to sovereign ratings.

Political factors, including the level of democratization, the degree of plurality, the division of powers, the orderly transition of heads of government and other officials, freedom of the press, the support for policy making, the strength of institutions, public security, and geopolitical considerations are critical to sovereign ratings. The economic structure and growth prospects of an economy are key considerations in analyzing sovereign ratings. The indicators used for this purpose include measures for income (GDP, per capita GDP, and real GDP growth and its components); savings and investment levels in relation to GDP; open unemployment; prices (CPI, WPI, GDP deflator); and exchange rates (flexible vs. fixed; real exchange rate as a measure of international competitiveness). Other factors that are more difficult to quantify are also taken into account, such as the diversification of the economy, the level of economic development and income distribution in the country, labor market flexibility, the efficiency of the public sector, and the degree of financial sector intermediation.

The economic structure and growth prospects of an economy are key considerations in analyzing sovereign ratings. The indicators used for this purpose include measures for income (GDP, per capita GDP, and real GDP growth and its components); savings and investment levels in relation to GDP; open unemployment; prices (CPI, WPI, GDP deflator); and exchange rates (flexible vs. fixed; real exchange rate as a measure of international competitiveness). Other factors that are more difficult to quantify are also taken into account, such as the diversification of the economy, the level of economic development and income distribution in the country, labor market flexibility, the efficiency of the public sector, and the degree of financial sector intermediation. Fiscal flexibility is another major determinant of sovereign ratings. This includes not only an analysis of fiscal flows (revenue, expenditure, balance) but also of stocks (debt levels, debt burden) and off-budget and contingent liabilities (unreported and contingent claims on government resources such as, for example, those resulting from the up-front fiscal costs of banking-system collapses). The fiscal situation of different levels of government—that is, the central government, the general government (central government plus local governments), and the consolidated public sector (general government plus state-owned enterprises)—is often analyzed separately.

Fiscal flexibility is another major determinant of sovereign ratings. This includes not only an analysis of fiscal flows (revenue, expenditure, balance) but also of stocks (debt levels, debt burden) and off-budget and contingent liabilities (unreported and contingent claims on government resources such as, for example, those resulting from the up-front fiscal costs of banking-system collapses). The fiscal situation of different levels of government—that is, the central government, the general government (central government plus local governments), and the consolidated public sector (general government plus state-owned enterprises)—is often analyzed separately. Monetary and liquidity factors are used to analyze inflationary conditions and exchange-rate sustainability. Indicators used include domestic credit to the private sector, monetary aggregates (including M1, M2, and so on) in relation to international reserves, short-term interest rates, core and nominal inflation, and a liquidity ratio (external liabilities of banks vs. external assets). The health of the banking system is measured by the degree of nonperforming loans and capital adequacy. Consistency between exchange rate and monetary/credit policies and institutional factors such as central bank independence are also taken into account.

Monetary and liquidity factors are used to analyze inflationary conditions and exchange-rate sustainability. Indicators used include domestic credit to the private sector, monetary aggregates (including M1, M2, and so on) in relation to international reserves, short-term interest rates, core and nominal inflation, and a liquidity ratio (external liabilities of banks vs. external assets). The health of the banking system is measured by the degree of nonperforming loans and capital adequacy. Consistency between exchange rate and monetary/credit policies and institutional factors such as central bank independence are also taken into account. External payments and debt is the category used to ascertain the adequacy of international reserves and the availability of foreign-exchange earnings that the country has in order to service its liabilities. This category is used to analyze both balance of payments flows and the stock of international debt. Indicators used include BOP data: trade balance (exports, imports, balance); current account (trade balance; factor payments, including interest and dividends; transfers); capital and financial account (net foreign direct investment and net borrowing). The composition of the current and capital and financial accounts are taken into consideration, as is the adequacy of international reserves and access to international capital markets. Important ratios in this category include the share of the current account deficit covered by foreign direct investment and the months of imports covered by international reserves.

External payments and debt is the category used to ascertain the adequacy of international reserves and the availability of foreign-exchange earnings that the country has in order to service its liabilities. This category is used to analyze both balance of payments flows and the stock of international debt. Indicators used include BOP data: trade balance (exports, imports, balance); current account (trade balance; factor payments, including interest and dividends; transfers); capital and financial account (net foreign direct investment and net borrowing). The composition of the current and capital and financial accounts are taken into consideration, as is the adequacy of international reserves and access to international capital markets. Important ratios in this category include the share of the current account deficit covered by foreign direct investment and the months of imports covered by international reserves. Reporters need to find out who are the rating agencies analysts for the country in question and try to get to know them. Contact should be made with analysts from the investment banks and with the IMF External Relations Department and other relevant staff.

Reporters need to find out who are the rating agencies analysts for the country in question and try to get to know them. Contact should be made with analysts from the investment banks and with the IMF External Relations Department and other relevant staff. What are the key issues that the rating agencies/IMF/investment banks are looking at?

What are the key issues that the rating agencies/IMF/investment banks are looking at? Reporters should send relevant published stories on the countries covered to the rating agencies/IMF/investment banks to establish credentials as a knowledgeable source. This could help develop a mutually beneficial relationship.

Reporters should send relevant published stories on the countries covered to the rating agencies/IMF/investment banks to establish credentials as a knowledgeable source. This could help develop a mutually beneficial relationship. Reporters should exploit the pressure analysts feel to be “in the news.”

Reporters should exploit the pressure analysts feel to be “in the news.” Who, where, and what are the sources of information for these analysts, and how reliable are they?

Who, where, and what are the sources of information for these analysts, and how reliable are they? What other sources of information are there that may have been overlooked or to which reporters have easier access?

What other sources of information are there that may have been overlooked or to which reporters have easier access? Reporters should beware of methodological differences that may lead to differences in results.

Reporters should beware of methodological differences that may lead to differences in results. Reporters should beware of a herd instinct by ratings agencies as a result of having the same sources of information and pressure from the markets.

Reporters should beware of a herd instinct by ratings agencies as a result of having the same sources of information and pressure from the markets. The records of analysts on particular topics should be examined closely. Reporters should return to the issues six or twelve months later to see whether the analysts proved to be correct.

The records of analysts on particular topics should be examined closely. Reporters should return to the issues six or twelve months later to see whether the analysts proved to be correct. Analyses should be focused on some of the issues discussed here with the purpose of creating debate and improving the ratings.

Analyses should be focused on some of the issues discussed here with the purpose of creating debate and improving the ratings.