INTRODUCTION

UNDERSTANDING ACCOUNTING is essential to understanding what is happening in the world of business. And yet, until recently, accounting and the accounting profession did not receive much press from the mainstream media. Sure, a few journalists followed the profession and its standard-setting bodies. The U.S. financial press did some reporting on accounting scandals, including those of the mid-1990s that involved top executives at certain firms attempting to “manage earnings” in order to keep stock prices high. But more often than not, mainstream press coverage either glossed over how businesses accounted for their activities or offered the firm’s own—and often incorrect—analysis and interpretation of its financial data. The healthy journalistic skepticism toward public-relations announcements found in other areas of the media was sadly lacking where accounting matters were involved.

It was the spectacular fall of two U.S. companies in late 2001 and early 2002, caused in large part by the market’s reaction to the accounting scandals that engulfed each, that catapulted the topic of accounting into the media at large. Energy giant Enron and telecommunications firm WorldCom revealed they had hidden liabilities, understated expenses, or employed other questionable accounting devices to maintain stock prices at artificially high levels. Outside auditors had attested to the fairness of these companies’ financial statements, as auditors do for all financial statements of public companies. In Enron’s case, this approval came from the Houston office of the global accounting firm Arthur Andersen. This office, and later the entire firm, was accused of obstructing justice by destroying documents that were pertinent to the government’s investigation of the Enron scandal (Andersen also audited WorldCom). This led to the demise of Andersen, considered by many to be the world’s preeminent accounting firm.

Enron and WorldCom were not the first companies to be involved in accounting scandals. Nor was Arthur Andersen the first accounting firm to get in trouble for attesting to the fairness of financial statements that later turned out to be questionable. It was the scope of the Enron scandal and the probing examination of “all things accounting” that soon followed that distinguished these scandals from the ones before it.

The events of the last two years have shown that every business journalist in the United States and abroad—whether he or she covers energy, equities, privatizations, or even entertainment—needs to know the basics of accounting. Using numbers instead of words, accounting chronicles the story of a company over time and at particular points in time—from its inception to its consolidation or, perhaps, its liquidation—as it grows or shrinks or simply stagnates. As with any unfolding story, it is imperative that journalists understand what is behind the elements that go into the story.1

This chapter will seek to provide journalists with an understanding of the varied underlying elements that ultimately define the makeup of the financial statements of multinational companies. It will also discuss the larger institutional context in which financial reporting takes place and how it is rapidly changing. This context has taken on an even more important role in the era of globalization, in which business knows no borders. The most important changes in that institutional context include

the formation of the International Accounting Standards Board in 2000 (with a formal board taking office in January of 2001);

the formation of the International Accounting Standards Board in 2000 (with a formal board taking office in January of 2001); the decision by the European Union to require all companies that list on European exchanges to adopt IASB pronouncements or International Financial Reporting Standards by 2005;2

the decision by the European Union to require all companies that list on European exchanges to adopt IASB pronouncements or International Financial Reporting Standards by 2005;2 the efforts to harmonize all national accounting standards, especially those of the U.S. Financial Accounting Standards Board with those of the IASB; and

the efforts to harmonize all national accounting standards, especially those of the U.S. Financial Accounting Standards Board with those of the IASB; and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in the wake of the Enron and WorldCom scandals. This legislation paves the way to tougher regulation of financial reporting, auditing, and corporate governance.

the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in the wake of the Enron and WorldCom scandals. This legislation paves the way to tougher regulation of financial reporting, auditing, and corporate governance.Journalists need to be aware of the full breadth of these institutional changes in order to adequately report on business matters involving international accounting.

WHAT IS ACCOUNTING?

Accounting3 has been defined as the “process of gathering, compiling, and reporting the financial history of an organization.”4 Just as historians of any subject have developed tools and methods to establish what occurred, accountants too have developed their own tools and methods. These methods, such as double-entry bookkeeping and systems of internal accounting control, capture the information required to relate the financial history of a business, nonprofit organization, or governmental entity. Their final product is not a book or an article but, instead, the financial statements included in public reports.

A company’s financial history “is distinguished by the use of economic concepts, accounting conventions, and institutional pressures that guide its construction.”5 This financial history is captured in financial statements that entities issue on a periodic basis, including yearly audited financial statements. (Full financial statements come out once a year. Interim statements, which are generally issued quarterly and tend to be unaudited, are not as complete and should not be substituted for the annual report.) With minor national variations, those financial statements generally consist of the following:

Balance sheet, or statement of financial position. A balance sheet presents a picture of a company’s wealth on one particular day. It shows what the company has (assets), what the company owes (liabilities), and the difference between the two, which is the equity of the owners. (Assets = Liabilities + Stockholders’ equity).

Balance sheet, or statement of financial position. A balance sheet presents a picture of a company’s wealth on one particular day. It shows what the company has (assets), what the company owes (liabilities), and the difference between the two, which is the equity of the owners. (Assets = Liabilities + Stockholders’ equity). Income statement and statement of shareholders’ equity. The income statement provides relevant information about an entity’s revenues, expenses, gains, and losses that can be used to analyze how the company did in the past and judge how it might do in the future. The statement of shareholders’ equity gives the amount and sources of the changes in equity that result from transactions with shareholders.

Income statement and statement of shareholders’ equity. The income statement provides relevant information about an entity’s revenues, expenses, gains, and losses that can be used to analyze how the company did in the past and judge how it might do in the future. The statement of shareholders’ equity gives the amount and sources of the changes in equity that result from transactions with shareholders. Statement of cash flows. The statement of cash flows gives information about the cash receipts and cash payments of an organization, in other words, the money going in and out of a company, during a certain amount of time. It is fundamental for assessing a company’s ability to pay off its debts.

Statement of cash flows. The statement of cash flows gives information about the cash receipts and cash payments of an organization, in other words, the money going in and out of a company, during a certain amount of time. It is fundamental for assessing a company’s ability to pay off its debts. Notes to financial statements. The notes are an integral part of financial statements, often containing information about the business that is not found elsewhere. The notes include information about the nature of an entity, the accounting practices and rules followed in preparing the financial statements, and contingencies that could affect the future financial condition and performance of the entity.

Notes to financial statements. The notes are an integral part of financial statements, often containing information about the business that is not found elsewhere. The notes include information about the nature of an entity, the accounting practices and rules followed in preparing the financial statements, and contingencies that could affect the future financial condition and performance of the entity.Inherent in financial statements are a host of estimates, assumptions, and judgments that involve varying degrees of subjectivity. For example, the calculation of expenses such as bad debts and depreciation depends on estimates. For bad debts, such an estimate involves judgments about whether certain customers will pay all (or a portion) of the amounts they owe. In the case of depreciation, estimates must be made about the useful productive lives of buildings, machinery, and other long-lived assets. Such estimates, besides dealing with rather straightforward issues such as how long a building can stand, must also take into account much more subtle questions such as technological change that can lead to obsolescence for a machine far before it physically wears out.

Likewise, the values attached to many assets and liabilities depend on estimating fair values where no active markets (such as the New York Stock Exchange) exist for these assets or liabilities. These values also may involve estimates of the effects of future events. For example, companies that hold investments in biotechnology start-up ventures that are trying to develop cures for cancer and other diseases need to assign values to such investments. That valuation process involves, among other matters, estimates and judgments about both the scientific and commercial feasibility of any products ultimately developed in such ventures. Accountants must also deal with uncertainty in developing these estimates. In the case of liabilities, determining the ultimate amounts a company will pay pensioners some forty or fifty years in the future involves estimates based on assumptions about many future events (for example, when employees will retire, interest rates in the future, returns on investments, and so on).

As we have seen, an accountant’s job is to chronicle the financial history of a business, nonprofit organization, or governmental entity. He does this by attempting to measure an entity’s wealth and the changes in its wealth. This measurement is based on three fundamental concepts, namely:

financial value

financial value wealth

wealth comprehensive income6

comprehensive income6Financial value, for purposes of accounting, generally represents the amount of money a company would receive if it sold an item or the item’s value in its current use to the company. For example, the value of an entity’s investment in U.S. Treasury notes would be the market value of the notes based on their price in bond markets where such financial instruments are traded. The value of a plant used to manufacture computers (and that the company is not holding as investment for future sale), on the other hand, would be its value “in use,” which is generally its acquisition cost minus accumulated depreciation.

Depreciation, for accounting purposes, is not intended to be a measure of how much a long-lived asset such as a manufacturing plant decreases in value. Rather, it is an accounting convention used to allocate the cost of such long-lived assets by expensing them over the periods they benefit. For example, a computer that cost $5,000 with a five-year useful life would be expensed through five yearly depreciation charges of $1,000. In those cases, however, where it is expected that the products produced by the plant are going to bring in less cash than it costs the company to carry the plant, or its acquisition cost minus accumulated depreciation, the company would record an “impairment” loss to reflect the decrease in the value “in use” of this plant.

Wealth represents the total financial values of all the things an entity owns or controls by other means minus the financial value of what it owes to others. For example, if a newly formed company had one asset, a plant costing $100,000 that was financed by $50,000 of cash invested by the company’ shareholders and a $50,000 loan evidenced by a mortgage, the company’s wealth would be $50,000.

Comprehensive income measures the changes in an entity’s wealth over time but does not take into account any changes that come about because of what shareholders invest or receive in dividends.7

While the above-mentioned concepts are essential to understanding what goes into measuring an entity’s wealth and changes in that wealth, they do not offer a concrete way to chronicle these changes. This is why accounting conventions, or the rules under which accountants record the financial history of an entity, are needed. Accounting conventions translate the broad abstract concepts that define wealth into concrete rules that can be applied to different types of transactions. That translation often involves compromising the intellectual purity of these concepts in the interest of producing standards that are workable and capable of being consistently applied by different preparers. Commonly referred to as “generally accepted accounting principles,” or GAAP, such rules have developed (generally on a national basis) to ensure some degree of consistency and comparability in reporting.

Accounting rules, or conventions, address three areas:

measurement

measurement recognition

recognition disclosure8

disclosure8Measurement rules specify how financial values are assigned to the items included in financial statements. For example, investments in marketable securities are generally shown at current market values, not at the cost for which they were acquired. Properties such as office buildings, on the other hand, are generally shown at what it cost to buy them, minus accumulated depreciation, or an allocation of that cost over time, even if they have since increased substantially in value.

Recognition rules govern “the process of formally recording or incorporating an item into the financial statements of an entity as an asset, liability, revenue, expense, or like item.”9 The financial statements included by multinational companies that are filed with different national securities regulators such as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission must be prepared using recognition rules that are consistent with the accrual method of accounting. Accrual accounting requires that assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses must be recorded when the transaction actually happens and not just when the company receives the money.10 For example, the sale of a product is generally recorded (or recognized) as an asset (for example, an account receivable) and revenue when the buyer actually receives the product and not when he or she pays for the item in cash. Similarly, a company generally must recognize a liability (or an account payable) and an expense in the period in which it receives a service or product, not in the period in which it pays the supplier.

Disclosure rules mandate additional information about the entity and its accounting conventions that must also be included in financial statements to be presented in accordance with GAAP. Many of these required disclosures are made in the notes to the financial statements.

GENERALLY ACCEPTED ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES

Accounting standards have historically been established on a national level, resulting in major differences between the standards of different countries. At present, U.S. GAAP, issued by the U.S. standards setter, the Financial Accounting Standards Board, is more common in the United States, while International Financial Reporting Standards are more common elsewhere in the world. A number of differences exist between U.S. GAAP and IFRS that affect comparisons of financial statements of multinational corporations involved in the same industry. There is, however, a strong movement afoot to harmonize national standards and establish international accounting standards. That subject is discussed in greater detail in a later section of this chapter.

PURPOSES AND BASIC COMPONENTS OF FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

BALANCE SHEET/STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION

The balance sheet presents a picture of a company’s wealth on one particular day: it shows what the company has (assets), what the company owes (liabilities), and the difference between the two, which is the equity of the owners. Information provided in the balance sheet, used with the notes and information in other financial statements, will help journalists assess the financial condition of a company. It will aid them in ascertaining its liquidity (can the company pay its bills tomorrow?) and solvency (does this company have the resources to stay in business?). Among other things, the balance sheet gives some idea of how much cash should come into the company as a result of resources the company owns or controls. It also shows, either directly or indirectly, how much cash the company needs to have on hand in order to pay the majority of its debts.11

One side of the balance sheet shows the resources that the company has (assets); the other shows how these resources are being financed, either by obligations to outsiders (liabilities) or by owners’ equity. Assets represent “probable future economic benefits obtained or controlled by a particular entity as a result of past transactions or events.”12 Assets may consist of tangible resources, such as a plant or factory, intangible resources, such as a patent, or claims against others, such as accounts receivables. The common characteristic is that each such resource or claim is going to produce cash: The company’s factory makes products that are sold for cash. The company’s patents give it the exclusive right to produce something that is later sold for cash. A customer or supplier will pay cash to settle his or her claim.

An asset is an asset only if the economic benefit it provides is the sole property of an entity—or under its sole control. No other entity can have access to the economic benefit, or it is not considered an asset. For example, companies cannot claim as an asset access to a river that helps power a plant, even if they have helped to clean up the river.13 In addition, for an item to qualify as an asset, the company must have it in its possession, that is, the transaction or event giving rise to the entity’s control of benefit must have already occurred.

But in order to gain economic benefits, a company usually needs to make economic sacrifices. The second half of the balance sheet begins by detailing these sacrifices, or liabilities. Liabilities represent “probable future sacrifices of economic benefits arising from present obligations of an entity to transfer assets or provide services to other entities as a result of past transactions or events.”14 In other words, the company’s future potential cash flow will be affected because of something—either cash or services—that it owes to someone else, like a supplier (accounts payable) or an employee (accrued wages).

A liability is only a liability if there is no way around the economic sacrifice that it supposes. In addition, the obligation arising from the liability must arise from a past transaction or event, such as work done by an employee or the receipt of goods or services from a supplier. Many, but not all liabilities are based on contracts and other legally enforceable agreements such as agreements to pay suppliers and employees for goods and services they provide.

After detailing assets and liabilities, the balance sheet then goes on to look at owner’s equity. Equity is defined as the interest of shareholders in a company, represented by the difference between total assets and total liabilities.15 The equity in a corporation (the most common form of business enterprise engaged in international activities) is generally referred to as shareholders’ equity and includes two distinct components. The first component is the equity that results from what owners contribute to and receive from the company, that is, the purchase of shares and the receipt of dividends by shareholders in a corporation. The second component is the equity that comes about as a result of the entity’s profit-seeking activities or, in other words, the revenues and gains that the company generates beyond expenses and losses.

Equity from shareholders can take the form of common stock, and, in certain cases, preferred stock. Common stock is a piece of paper that represents a “piece” of a corporation. If you hold common stock, you hold ownership in a company. Common stock holders do very well if the company does well and the price of the stock goes up because they can sell their ownership—or shares of stock—at a higher price. But, if the entity fails, common shareholders are last in line to get distributions.

Preferred stock represents a claim on the assets of the entity that takes precedence over the claims of common shareholders. The nature of the preferences given to this class of shareholders may differ from entity to entity. Usually, holders of preferred stock receive dividends at a stated rate before any dividends are paid to common shareholders. If the entity fails and has to be liquidated, preferred shareholders are first in line (after creditors) to get distributions before common shareholders.

Retained earnings represent all the equity produced by a company’s operations since it began (equivalent to its accumulated profits and losses included yearly in net income) minus all the dividends that have been paid to shareholders. For example, if a company began business on 1 January 2001 and had a net income of $10,000 in 2001 and a net loss of $5,000 in 2002, its retained earnings as of 31 December 2002 would be $5,000. Distributions of dividends to shareholders generally must be made from retained earnings.

INCOME STATEMENT

The second and, in the opinion of many analysts, the most important financial statement is the income statement, which in certain countries is called the profit and loss account. The purpose of this statement, which is also known as the earnings statement, is to provide information about an entity’s revenues, expenses, gains, and losses, that is, the resources that come into a company and those that go out, as well as the amount left over to add to the company’s equity. This statement can help journalists analyze how a company did in the past and judge how it might do in the future. It can also give journalists certain information needed to assess the future earnings and cash flows of a company.

An income statement, which captures a company’s activities during a certain time period between two balance sheets, reflects the changes in net assets in the balance sheet that result principally from the “operations” of a company. As indicated above, the income statement shows the relationship of four elements—revenues, expenses, gains, and losses.

Revenues are increases in assets or decreases in liabilities or a combination of both that result from a company’s central operating activities.

Expenses are decreases in assets or increases in liabilities or a combination of both that result from a company’s central operating activities.

Gains are similar to revenues, in other words, they increase assets or decrease liabilities, except that they result from peripheral activities of an organization.

Losses are similar to expenses—they decrease assets or increase liabilities, except that they result from peripheral activities of an organization.16

The most important thing to remember about the differences between revenues and gains and expenses and losses, respectively, is that both are directly related to a company’s definition of its central operating activities. Dell describes itself as “the world’s leading computer systems company” in its company overview on its Web site, so when Dell sells a laptop it considers the selling price to be revenue. But when it sells one of the marketable securities it holds as a short-term or long-term investment it considers the difference between the selling price and the amount it paid to acquire that investment as either a gain or loss. Dell considers the cost of producing the laptop sold as an expense but views the decrease in the value of a building destroyed by fire as a loss.

Unlike the balance sheet, the format of the income statement is not the same for all companies. Companies differ not only on how many intermediate items, such as gross margin and operating income, they include before showing the final total of net income, they also differ on how to define—and calculate—these intermediate items. For example, there is no definition of operating income in authoritative accounting literature. That means that this important measure of performance may be calculated differently for companies in the same industry. Journalists need to be aware that they might not be able to compare the operating income of two companies that appear to be in the same business.

STATEMENT OF SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY

The principal purpose of this statement is to report the amount and the sources of the changes in equity that result from transactions with shareholders. For this reason, the statement of shareholders’ equity reports the changes in each of the components of equity in the balance sheet, or the changes in common stock and preferred stock. In addition, for companies that follow U.S. GAAP, this statement also reports in most cases the changes in other comprehensive income. As noted in an earlier section of this chapter, comprehensive income is defined in U.S. GAAP as all changes in equity except for what shareholders invest or receive in dividends. It is a broader concept than net income.

Comprehensive income, in turn, is divided into two components—net income and other comprehensive income. The changes in equity that enter into net income are displayed in the income statement. Other comprehensive income, on the other hand, includes “revenues, expenses, gains, and losses that under [U.S. GAAP] are included in comprehensive income but excluded from net income.”17 This is where most of the effects of foreign currency fluctuations are accounted for.

Under current U.S. GAAP, two of the most important items included in other comprehensive income are (1) unrealized gains and losses on certain investments in marketable securities and (2) certain unrealized gains and losses arising from the use of derivatives as hedging instruments. The rationale for excluding such items from net income, which has the effect of including them in other comprehensive income, has been that the volatility of such items would distort the analysis of a company’s performance. Not all accountants and standard setters agree with this argument. In their ongoing projects on reporting financial performance, both the FASB and IASB have tentatively decided to eliminate the option to display items of other comprehensive income in a separate financial statement.

STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS

The statement of cash flows provides information about the money going in and out of an organization during a period of time. That statement can help journalists answer the following questions:

How much cash have the company’s operations produced?

How much cash have the company’s operations produced? What are the other sources of cash besides operations, like investment and debt?

What are the other sources of cash besides operations, like investment and debt? Can this company pay its debts?18

Can this company pay its debts?18When looking at the cash flow statement, it is important to remember that this is the only one of the financial statements that is calculated by the cash-based method of accounting, as opposed to the accrual method of accounting. Accrual accounting requires that assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses must be recorded when the transaction actually happens and not just when the company receives the money. The cash flow statement shows when cash actually comes into and goes out of the company.

In order to show the different sources of cash, the statement of cash flows separates cash receipts into three distinct categories—(1) financing activities, (2) investing activities, and (3) operating activities. Cash receipts and payments from financing activities represent the cash that comes into and goes out of the entity as it issues and sells debt and shares of its different classes of stock. Cash receipts and payments from investing activities take into account the cash that comes into and goes out of an entity as it buys and sells long-term assets, such as property, plant and equipment, and long-term investments. Cash receipts and payments from operating activities generally include the cash that comes from carrying out the business activities that are central to operations, for example, production and sale of major products.

Many financial analysts believe that the cash flow statement presents the most accurate picture of a company’s health. This is because it shows how money is moving through the business without any reflection of the different accounting treatments (such as calculations based on subjective variables like depreciation and estimate of bad debts) used in other financial statements to get the final numbers. This does not mean, however, that the numbers in the cash flow statement are foolproof. As with all parts of the financial statements, the numbers are only as good as the information behind them, which brings us to the next section.

NOTES TO FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

It is absolutely essential to read these notes in order to understand and/or analyze a company and its business. An enormous amount of information that is vital to a journalist’s understanding of a company is contained in the notes. The types of notes to financial statements fall into four broad categories, namely:

Summary of significant accounting policies

Summary of significant accounting policies Detailed disclosures for specific assets, liabilities, and equity

Detailed disclosures for specific assets, liabilities, and equity Disclosures for specific revenue and expense categories

Disclosures for specific revenue and expense categories Other note disclosures, such as where the company does business around the world and what percentage of the company’s net revenue and operating income come from these different segments

Other note disclosures, such as where the company does business around the world and what percentage of the company’s net revenue and operating income come from these different segmentsAll of the notes to the financial statements must be read carefully if a journalist truly wants to understand a company’s financial statements. The first category, the note or notes that set forth the summary of significant accounting policies may, however, be the most important type, as it summarizes the various accounting policies and rules adopted by the company. (If there has been a change in accounting policy that is material, mention of this would also appear in the auditor’s opinion.)

The other categories are also quite important in understanding individual asset, liability, revenue, and expense items. That importance is illustrated in the section of this chapter that examines the Dell balance sheet and income statement. Therein are continuing references to various notes to the Dell financial statements that contain important information about specific assets, liabilities, revenues, expenses, gains, and losses.

ANALYSIS OF DELL’S CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION AND INCOME STATEMENT

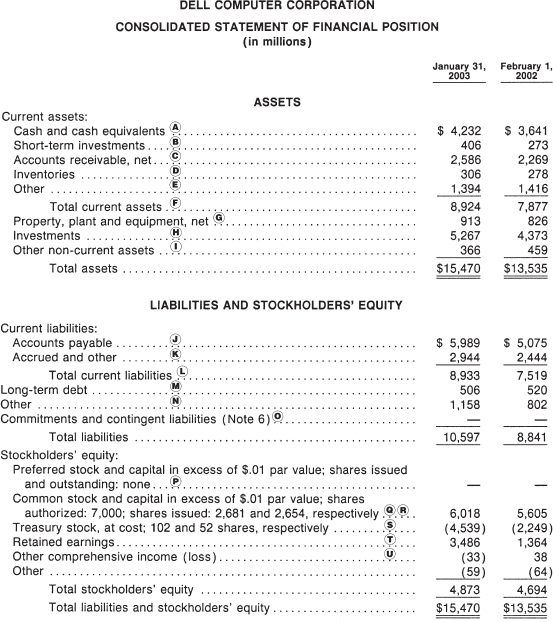

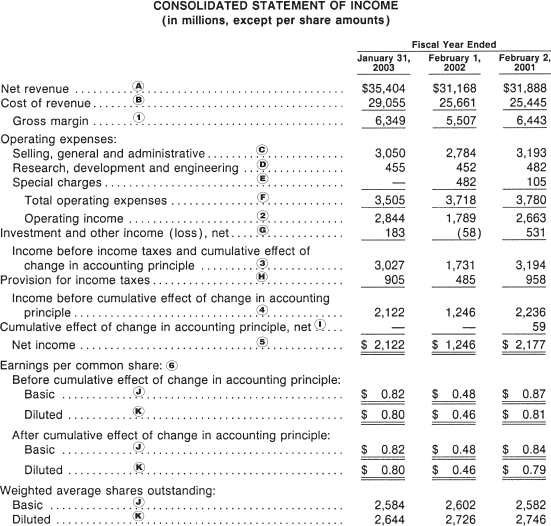

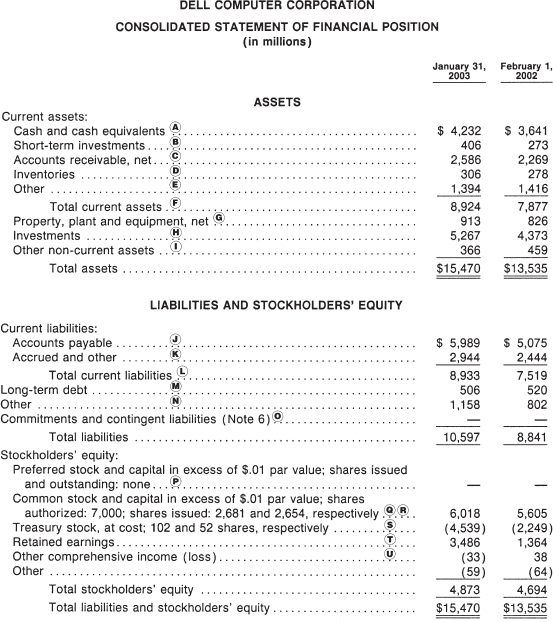

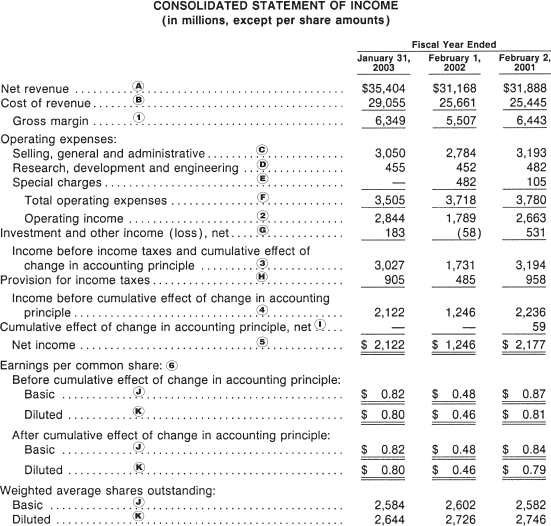

This section of the chapter examines in detail actual financial statements of a well-known multinational, Dell Computer Corporation (Dell), that are prepared in accordance with U.S. GAAP. The purpose of such an examination is to illustrate certain concepts discussed in the earlier section. This section is organized in the following way: The “Consolidated Statement of Financial Position,” or “Balance Sheet,” is reproduced on page 211 and the “Consolidated Statement of Income” for the fiscal year ended 31 January 2003 on page 212. A letter or number reference has been added for each item on both statements. The letters and numbers refer to explanations of the nature of each item that are included in “Explanation of References” on pages 213 to 219. These statements were taken from the 2003 Dell Corporation 10K; please refer to that document for the complete Dell Corporation financial statements and accompanying footnotes.

For the sake of brevity, the notes to the financial statements are not reproduced here. However, when a specific reference is made to something in the notes, an endnote appears to guide readers to this reference in documents readily available online.

EXPLANATION OF REFERENCES

CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION

Assets

A. Cash and cash equivalents. All companies need to have hard currency on hand or within reach. Cash represents the actual funds available to the company in petty cash or an account at a local bank. Cash equivalents generally refer to highly liquid investments such as U.S. Treasury Bills and bank certificates of deposits that have original maturities of three months or less at the date of purchase.

B. Short-term investments. Those investments in financial instruments such as treasury notes and commercial paper whose maturity is more than three months at the date of purchase but less than a year.

C. Accounts receivable, net. The amount that the company stands to receive from customers in exchange for filling an order. “Net” means an allowance for those accounts considered to be uncollectable has been subtracted from total amount owed to Dell by customers. Normally, the amount of such allowance will be disclosed on the face of the balance sheet or in the notes to the financial statements. Dell discloses this information (allowance = $71) in note 10 to its financial statements, “Supplemental Consolidated Financial Information.”19

D. Inventories. Items that a company has in stock for sale or items that are used to produce what is sold. In the case of Dell, this asset category would include both finished products—for example, desktop and notebook computers—as well as the components that go into making those finished products. The amount of each of these categories of inventory is disclosed in note 10 to the Dell financial statements.

E. Other. In preparing financial statements, an entity is permitted to combine accounts with smaller balances in one caption. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has a general rule that any assets with balances that are equal to or greater than 5 percent of total current assets need to be listed separately on the balance sheet.20 This caption probably includes items such as prepaid insurance, deposits, and other items that will benefit operations within one year of the balance sheet date and therefore are included in current assets.

F. Total current assets. The authoritative accounting literature uses the term “current assets” to refer to cash and other assets that most likely will be converted into cash within the current operating cycle. For example, inventory sold becomes an account receivable from customer, who then pays in cash, during the normal operating cycle of the business, which is generally considered to be one year.21

G. Property, plant and equipment. Office buildings, manufacturing plants, and manufacturing and office equipment that Dell owns or leases in order to conduct its business. The amounts of each of the subcategories making up this category are disclosed in note 10 to the Dell financial statements. Assets in this category must satisfy the following conditions. They must be: “acquired for use in operations and not for resale; … long-term in nature [i.e., they have a productive life of more than one year] and usually … subject to depreciation; [and they must] possess physical substance.”22

H. Investments. Financial instruments such as shares of stocks and bonds. Dell discloses in note 2 to its financial statements that “all investments with remaining maturities in excess of one year are recorded as long-term investments.”23

I. Other non-current assets. Again, a grouping of assets, in this case all noncurrent, or those that do not meet the definition of current assets in (F) above, that did not reach the required threshold for separate disclosure.

Liabilities

J. Accounts payable. What companies owe to suppliers for goods and services that have already been received. Amounts included here are generally based on bills received from suppliers.

K. Accrued and other. These current liabilities represent other obligations related to the current operating cycle that are disclosed in detail in note 10 to the Dell financial statements. This category includes obligations related to warranties, employees’ wages, deferred income, sales and property taxes, income taxes, and so on. In many cases, the amount for each such item must be estimated.

L. Total current liabilities. Those obligations such as accounts payable or accrued liabilities that a company must use its existing resources, or current assets, to pay off.24 If a company does not have enough total current assets to cover this category, it must borrow in order to do so.

M. Long-term debt. Any kind of formal promise to pay back notes or bonds in the future. Since these payments are not due until more than one year from the date of the balance sheet, they are classified as long-term liabilities. It is always important to read the note associated with this category for more information on the terms of the debt and its repayment. Note 2 to the Dell financial statements in a section labeled “Long-Term Debt and Interest Rate Risk Management” spells out the specific terms of this debt—that is, interest rate, repayment date(s), and other important provisions—as required by U.S. GAAP.

N. Other. A grouping of liabilities, all noncurrent, that do not reach the required threshold for separate inclusion on the balance sheet. Dell discloses the items that make up this total in note 10 to its financial statements.

O. Commitments and contingent liabilities. U.S. GAAP defines a contingency as “an existing condition, situation, or set of circumstances involving uncertainty as to possible gain (a gain contingency) or loss (a loss contingency) to an enterprise that will ultimately be resolved when one or more future events occur or fail to occur.”25

Companies must recognize a loss and record a liability for loss contingencies when

“It is probable that assets have been impaired or a liability has been occurred,” that is, that the value of an asset has diminished or the company has incurred an obligation to another party;

“It is probable that assets have been impaired or a liability has been occurred,” that is, that the value of an asset has diminished or the company has incurred an obligation to another party;and

“The amount of the loss can be reasonably estimated.”26

“The amount of the loss can be reasonably estimated.”26Accounting standard setters use “probable” to mean that there is more than a 50 percent likelihood of the event occurring. Companies must disclose any unrecognized losses that arise from contingencies when a somewhat lower standard is met, that is, “when it is reasonably possible (more than remote but less than probable) that a loss has been incurred or it is probable that the loss has occurred but the amount cannot be reasonably estimated.”27

This is the category where companies reveal how any pending litigation, product recall, or environmental cleanup costs could affect the company positively or negatively. For example, a company that is being sued for $100 million dollars for delivering products alleged to be defective may be vigorously disputing the claim. Lawyers have advised the company that, in their opinion, it is not probable that the claim for that amount will be successful. Accordingly, the company has not recorded any liability for the claim. On the other hand, if the company’s lawyers do believe it is reasonably possible that some amount will be paid to settle the action but cannot reasonably estimate that amount, then a contingent liability exists that must be disclosed. Placing a caption on the face of the balance sheet (even though no amount is shown) is intended to emphasize the importance of such contingencies to the reader of the financial statements.

In note 6, “Commitments, Contingencies, and Certain Concentrations,” among other things, Dell lets investors know that the company is “subject to various legal proceedings … in the ordinary course of business” but underlines that it does not think that this will have any “material adverse effect” on earnings, operations, or future cash flows.28 In other words, Dell does not think that these proceedings with affect the company’s financial condition and bottom line.

Stockholders’ Equity

Note 4 to the Dell financial statements, “Capitalization,” describes the rights of each class of stock authorized and other important information about contributions made to Dell by owners.

P. Preferred stock. As we already discussed, preferred stock represents a claim on the assets of the entity that takes precedence over the claims of common shareholders. The nature of the preferences given to this class of shareholders may differ from entity to entity. Holders of preferred stock generally are not entitled to vote for directors or approve decisions of the directors. While Dell has the authority to issue five million shares of preferred stock, par value $.01 per share, no such shares have been issued.

Q. Common stock. Again, common stock is a piece of paper that represents one’s ownership in a corporation. As owners, holders of common stock usually get to elect the board of directors of the entity and approve the decisions of that board, such as deciding how much to pay executives and approving mergers and acquisitions. Common stock is generally reflected at what is called par value. Par value establishes the nominal value per share and is generally the minimum amount (established by state law) that must be paid by each shareholder when stock is issued. Corporations generally sell shares of their common stock for amounts greater than its par value.

R. Additional paid-in capital. The amount that stockholders have paid above par value to a company to acquire common stock. This amount is generally shown separately from par value of common stock outstanding. Dell, however combines the two amounts in one caption, Common stock and capital in excess of $.01 par value.

S. Treasury stock. The cost of shares repurchased by Dell on the open market and held by it for reissue, or what it costs the company to buy back its stock and hold it. Repurchases and reissuances are made for various purposes. In note 4 to its financial statements, Dell indicates it has a share repurchase plan “to manage the dilution resulting from shares [of common stock] issued under the Company’s employee stock plans.”29 This is just Dell’s way of recognizing that when it issues shares, this issue dilutes everyone else’s ownership and earnings per share. By repurchasing shares given to employees, Dell minimizes the effect of such dilution.

T. Retained earnings. This category principally represents the accumulated net income of Dell since its founding.

U. Other comprehensive income (loss). This category principally represents unrealized losses on certain derivative instruments.

“CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF INCOME”

The explanations below follow the order in which the captions appear in the Dell “Statement of Income.” Letter references such as (A) refer to items of revenues, expenses, gains, and losses in this statement. Numerical references such as (1) refer to intermediate totals in the statement.

A. Net revenues. Note 1 to the financial statements, “Description of Business and Summary of Significant Accounting Policies,” indicates that “net revenue includes sales of hardware, software and peripherals, and services (including extended service contracts and professional services).” As such, these activities constitute the major or central operations of Dell.30

B. Cost of revenue. The costs of products and services sold during the period, or how much it costs Dell to produce what it sells. This would include, for example, the costs of laptops sold and wages and other direct costs of employees performing professional services for Dell customers during the period.

1. Gross margin. The difference between net revenue and the cost of revenue, or sales revenue minus the cost of sales. This intermediate total may be a good indicator of the competitive pressures faced by company. For example, Dell’s gross margin dropped from 20.2 percent in 2001 to 17.6 percent in 2002 and 17.9 percent in 2003, an indicator of the fierce price competition that existed in the markets for computer systems, desktops, and laptops.

F. Total Operating Expenses. Dell divides these expenses into the following three categories:

C. Selling, general and administrative. This category includes all advertising and marketing expenses as well as most corporate overhead, including accounting and legal expenses.

D. Research, development and engineering. This category of expense consists of two distinct subcategories: (1) research and development and (2) engineering. Note 10 to the financial statements discloses the amount of each subcategory. Generally, research and development expenses have accounted for 70–75 percent of this category.

E. Special charges. This category consists of expenses incurred by Dell to get out of certain business activities in fiscal 2002 and 2001. Note 8 to the financial statements, “Special Charges,” details the nature of these expenses. They principally represent costs that arose from (1) severance packages and (2) closing facilities that Dell leased or owned.31

Because “special” charges, often characterized as “restructuring” charges, are supposed to be irregular and some companies have them year in and year out, the SEC requires extensive disclosure of the nature of such charges.

2. Operating Income. As previously discussed, there is no common authoritative definition of this term, so this measure of performance differs from company to company. Dell uses a straightforward notion of operating measure, which means that it includes most revenues, expenses, gains, and losses. Dell excludes three items from the measure: (1) certain revenues, expenses, gains, and losses included in the caption “Investment and other income (loss)” (details discussed below), (2) income taxes included in the caption “Provision for income taxes,” and (3) the cumulative effect of a change in accounting principles.

It is only in the first area (“certain revenues, expenses, gains and losses”) that Dell exercises judgment in developing an operating measure. Generally, such a measure is developed on a pretax basis and excludes income taxes. Moreover, U.S. GAAP requires the cumulative effect of an accounting change (details discussed below) to be shown separately after all other items in the income statement. Dell’s operating income as a percentage of total pretax income, or income before income taxes and the cumulative effect of change in accounting principle, ranged from 83 percent in fiscal 2001 to 103 percent in fiscal 2002 and 94 percent in fiscal 2003.

G. Investment and other income (loss), net. Note 10 to the Dell financial statements indicates that this caption includes investment income, primarily interest; realized gains (or losses) on investments; and small amounts of interest and other expenses.

3. Income before income taxes and cumulative effect of change in accounting principle. The pretax income of Dell.

H. Provision for income taxes. Taxes on pretax income either currently payable or payable in future years. Note 3 to the Dell financial statements, “Income Taxes,” spells out in great detail, as required by U.S. GAAP, the nature of such taxes.

4. Income before cumulative effect of change in accounting principle. The net income of Dell from activities during each of the respective years. Analysts tend to focus on this number, if it is present, rather than net income because, as explained below, the cumulative effect of the change in an accounting principle relates to matters affecting prior years.

I. Cumulative effect of change in accounting principle. Under current U.S. GAAP,32 changes in accounting principles are generally recognized by including the cumulative effect of such changes as of the beginning of the year, that is, the sum of such changes if they had been made in prior years, as a separate item in the income statement. Note 1, “Description of Business and Summary of Significant Accounting Policies,” indicates that in fiscal 2001, Dell changed its accounting for certain revenue to conform to a SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin. The note describes the nature of the change and its effect on the Dell financial statements.33

5. Net Income. The sum of revenues, expenses, gains, and losses included in items A–I.

6. Earnings per common share. This measure, which indicates the income earned by each share of common stock, has been widely used by journalists and others to evaluate and compare the performance of multinationals. Be careful, though. Many accountants and analysts believe that earnings per share may be an overly simplistic measure that, in certain cases, may mislead rather than inform. Where a cumulative effect of a change in accounting principle is present, as in the case of Dell, earnings per share must be shown both before and after such cumulative effect. In both instances, two measures—(J) Basic and (K) Diluted must be given. The difference in those two measures is explained below.

J. Basic. In this calculation, income before cumulative effect of change in accounting principle (see 3, above) and net income (see 5, above) are divided by the weighted average shares of common stock issued and outstanding during the year. A weighted average is used rather than the year-end number of shares issued and outstanding to take into account any issuances or repurchases of common stock by Dell during the year.

K. Diluted. In this calculation, the numerator remains the same as in the “basic” calculation. The denominator, however, is changed to show the effect on earnings per share of all additional shares that would arise if securities convertible to common stock were converted or stock options or warrants were exercised. This is a “what if” calculation, meaning, for example, what would be the effect on earnings per share if all stock options that were “in the money” (meaning that the exercise price of the option is below the market price of the stock) had been exercised during the year? In the case of Dell, such dilution is much more significant in the 2001 fiscal year than in either 2002 or 2003. As required, Dell shows the weighted average number of shares entering into both calculations of earnings per share.

DISCUSSION OF THE INSTITUTIONAL CONTEXT

The institutional context in which accounting takes place is in the midst of rapid change. Some of these changes are a natural result of globalization, which has transformed the way that companies do business and underscored the need for international accounting standards. Others have come about as a result of the recent spate of accounting scandals in the United States and abroad.

While numbers may be universal, the concepts that underlie them or the real life things that they represent are not. Culture and the particulars of a country’s economic and legal development have played an enormous role in determining national accounting standards.34 Different market cultures also play a role in determining accounting standards. In the United States, which has a long tradition of broad public-equity markets, companies are used to disclosing a good deal of information and know that they must do so in order to receive public investment. The situation is quite different in Europe, where the equity of companies, at least until recently, was closely held by a few individual families, governments, or private banks. Since the public had not invested in the fortunes of the company, there was little demand for public disclosure.35

So it is not surprising that traditionally each country had its own accounting standards. There was no such thing as an international accounting standard until 1973, when the International Accounting Standards Committee was established. The problem, of course, was which standard to use as the international standard. The United States, the United Kingdom, and other English-speaking countries such as Canada and Australia believed their national GAAPs to be more rigorous than European standards and the general international standards, which in certain cases were the result of numerous compromises between nations.

As this debate raged, markets were becoming more and more international, and an increasing number of companies began to list on foreign stock exchanges in order to raise money. In order to do so, companies had to reconcile their financial statements with the national accounting standards of each exchange where they chose to list. This meant that companies had to basically present two sets of numbers, which could be very different, depending on the accounting standards used. This was not only costly for the company but confusing to potential investors.

In the mid-1990s, the European Commission decided that European multinationals should follow international accounting standards.36 This was significant because international accounting standards, or those standards created by the IASC and later the IASB, were and still are considered stricter than individual European GAAPs. In 2000, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the government body that regulates the U.S. securities markets, announced that it supported the development of a high quality set of standards to be used internationally (without referring to any specific standard) for companies that wanted to sell securities in markets other than those of their home countries, also known as cross-border offerings.37 While this support did not translate into a requirement that all U.S. companies adopt international accounting standards, it did serve as a catalyst in the formation of the International Accounting Standards Board by accelerating cooperation among national standard setters, including the U.S. standards setter, the Financial Accounting Standards Board, and the IASC.

The IASC continued to grow in members and stature. In 1999, the International Accounting Standards Committee began a restructuring that would eventually transform it into the full-time International Accounting Standards Board. This new body came into being in January of 2001 and has begun to take the lead on moving all countries toward uniform accounting standards by 2005. This is when most companies that list on European Union exchanges will be required to adopt IASB pronouncements, or what are now known as International Financial Reporting Standards.38 Even though the United States had not officially said that it will adopt international accounting standards by 2005, the FASB has been working closely with the IASB over the last year to converge U.S. and IASB pronouncements.39

While IFRS are beginning to drive the debate on a number of issues, including expensing stock options and accounting for pension liabilities, not all is smooth sailing. Even as this book goes to press, there are still many difficulties to work out before IFRS are embraced worldwide.40

One criticism of international accounting standards in the United States has been that they are too vague. But in some respects, the argument that U.S. standards are better than international ones has become harder to defend in the wake of Enron and WorldCom. As of October of 2003, the SEC had yet to adopt IFRS across the board or allow foreign issuers to file according to these standards without reconciliation to U.S. GAAP (and there is no guarantee that this will change). That said, the SEC has tried to make things easier for foreign issuers in a number of ways, including providing different forms for registering securities based on internationally developed principles and more generous deadlines for reporting.

REGULATORY CHANGES THAT HAVE AFFECTED THE INSTITUTIONAL CONTEXT

There have been significant changes in regulation in the United States that affect both the accounting and the auditing profession in the United States and abroad. In the wake of the Enron and WorldCom scandals, the U.S. Congress passed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in July of 2002. This law—among other things—significantly increased the reporting requirements of both foreign and domestic companies listed in the United States. Under Sarbanes-Oxley, which made no outright distinction between domestic and foreign companies, the SEC was required to pass rules in a number of areas, including disclosure, the oversight of public accounting firms, the functioning of audit committees, and the nature of company reviews of internal controls.41

Equally important, if not more important, were the law’s provisions that removed the oversight of independent outside auditing firms and the setting of auditing standards from the accounting profession (the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, or AICPA) and vested those responsibilities in an independent board appointed by the SEC. This independent board, called the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, now has the job of regulating the actions of both domestic and foreign public accounting firms that audit the financial statements of companies that issue shares to the public in the United States.

Sarbanes-Oxley is especially significant because it has greatly expanded the SEC’s authority over matters of corporate governance.42 A number of the provisions of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act have been quite controversial both in the United States and abroad because they make much greater demands on companies in terms of corporate governance and auditing and reporting requirements. These provisions also increase the legal liability of companies and senior management. In addition to being uncomfortable for companies in the United States and abroad, foreign governments viewed some of the changes as impinging on national sovereignty. They have objected to the kind of rules placed on all firms and to what they see as the U.S. overstepping its jurisdiction.43 In cases where there is a direct conflict, the SEC has tried to make certain accommodations for foreign issuers.44 The PCAOB has also made accommodations with regard to regulation of foreign auditors, but even as this book goes to press there are still a number of issues to be worked out.

ADDITIONAL TIPS FOR READING FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF COMPANIES

“MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS”

In addition to reading the financial statements of a company, journalists should be sure to consult “Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations,” located in the annual report. This document gives journalists the company’s take on how the business did over the past year. In addition, it signals developments that could affect the business either positively or negatively in the upcoming year.

RATIOS

Ratios are a good way of cutting through the numbers of financial statements and putting companies in the same industry on common bases so they can be analyzed. But journalists do have to be careful that certain accounting differences are not distorting these numbers. Remember: ratios are only as good as the numbers behind them.

TIPS FOR READING BALANCE SHEETS AND STATEMENTS OF SHAREHOLDERS’ EQUITY

Inventory tends to be very specific to the business that a company is in. Some companies, by the nature of their business, have a lot of inventory. Others, like Dell, have very little. Journalists should also look at a company’s inventory in relation to its sales, in order to assess how quickly the company is turning over what it has in stock. It is a good idea to look at how this number has changed from previous years. (Inventory turnover = Sales/Inventory.)

Inventory tends to be very specific to the business that a company is in. Some companies, by the nature of their business, have a lot of inventory. Others, like Dell, have very little. Journalists should also look at a company’s inventory in relation to its sales, in order to assess how quickly the company is turning over what it has in stock. It is a good idea to look at how this number has changed from previous years. (Inventory turnover = Sales/Inventory.) Journalists can figure out the amount of money that a company would have after paying all its bills, or its net current assets, by subtracting current liabilities from current assets. (Net current assets = current assets - current liabilities.) Rather than looking at the absolute amount, however, a more useful figure for analyzing current assets is the current ratio, which is found by dividing current assets by current liabilities. (Current ratio = current assets/current liabilities.) There is no one correct current ratio figure, although some analysts believe a company should have twice the amount of assets as it does liabilities.45 But this varies depending on the type of business that the company is in.

Journalists can figure out the amount of money that a company would have after paying all its bills, or its net current assets, by subtracting current liabilities from current assets. (Net current assets = current assets - current liabilities.) Rather than looking at the absolute amount, however, a more useful figure for analyzing current assets is the current ratio, which is found by dividing current assets by current liabilities. (Current ratio = current assets/current liabilities.) There is no one correct current ratio figure, although some analysts believe a company should have twice the amount of assets as it does liabilities.45 But this varies depending on the type of business that the company is in. Journalists always want to look at a company’s level of debt and compare it to previous years. In order to truly understand the amount of debt that a company has, however, and how this level can affect the company’s prospects, journalists should refer to the balance sheet and footnotes, which give the particulars of debt, interest rates, and maturities. By reading this information, journalists should be able to ascertain what happened during the year to increase or decrease the company’s level of debt. Was the company relying on outside factors such as the stock market or acquisitions, as opposed to its core business, to maintain liquidity and solvency? Journalists should also look at the net increase in debt in the financing part of the cash flow statements.

Journalists always want to look at a company’s level of debt and compare it to previous years. In order to truly understand the amount of debt that a company has, however, and how this level can affect the company’s prospects, journalists should refer to the balance sheet and footnotes, which give the particulars of debt, interest rates, and maturities. By reading this information, journalists should be able to ascertain what happened during the year to increase or decrease the company’s level of debt. Was the company relying on outside factors such as the stock market or acquisitions, as opposed to its core business, to maintain liquidity and solvency? Journalists should also look at the net increase in debt in the financing part of the cash flow statements. One way of comparing the amount of debt that two companies in the same industry have is by calculating the debt-to-equity ratio, which is total liabilities divided by total shareholders’ equity. (D/E = total liabilities/total shareholders’ equity.) The more debt a company has, the more highly leveraged it is. If the ratio increases over a number of years, journalists probably want to investigate if this is due to a deteriorating financial condition or a strategy for financing.

One way of comparing the amount of debt that two companies in the same industry have is by calculating the debt-to-equity ratio, which is total liabilities divided by total shareholders’ equity. (D/E = total liabilities/total shareholders’ equity.) The more debt a company has, the more highly leveraged it is. If the ratio increases over a number of years, journalists probably want to investigate if this is due to a deteriorating financial condition or a strategy for financing. Journalists should be sure to examine the line that refers to “Commitments and contingent liabilities.” This is the category in which companies reveal how any pending litigation, product recall, or environmental cleanup costs could affect the company positively or negatively. It is important to read the note about this category because if indeed a company has to settle a claim—or stands to benefit from not having to settle a claim—this may have an enormous effect on its financial condition and bottom line. The company stands to gain or lose a lot of money.

Journalists should be sure to examine the line that refers to “Commitments and contingent liabilities.” This is the category in which companies reveal how any pending litigation, product recall, or environmental cleanup costs could affect the company positively or negatively. It is important to read the note about this category because if indeed a company has to settle a claim—or stands to benefit from not having to settle a claim—this may have an enormous effect on its financial condition and bottom line. The company stands to gain or lose a lot of money.TIPS FOR READING INCOME STATEMENTS

The format of the income statement is not the same for all companies. This is because companies differ on how many intermediate items, such as gross margin and operating income, they include before showing the final total of net income. They also differ on how to define—and calculate—these intermediate items. For example, there is no definition of operating income in authoritative accounting literature. In addition to making it difficult to compare companies in the same business, the fact that there is no one definition of operating income means that there has been some abuse in this category. Companies want to include revenues and gains in any measure of operations but want to exclude expenses and losses—because they know that analysts focus on “recurring operations” to get an idea of future earnings.

The format of the income statement is not the same for all companies. This is because companies differ on how many intermediate items, such as gross margin and operating income, they include before showing the final total of net income. They also differ on how to define—and calculate—these intermediate items. For example, there is no definition of operating income in authoritative accounting literature. In addition to making it difficult to compare companies in the same business, the fact that there is no one definition of operating income means that there has been some abuse in this category. Companies want to include revenues and gains in any measure of operations but want to exclude expenses and losses—because they know that analysts focus on “recurring operations” to get an idea of future earnings.For this reason, it is important to try to understand how a company distinguishes a “recurring” transactions or events from “nonrecurring” ones. For example, many companies have recently taken restructuring charges, which are supposedly nonrecurring, or irregular, events. But, since many companies have these nonrecurring charges year in and year out, it is a good idea to pay close attention to these special charges. Journalists should be sure to read the corresponding disclosure very carefully to see what a company defines as a “special” charge.

The intermediate total of gross margin, which is calculated by dividing gross profit by sales, shows the relationship between sales and how much it costs to produce those sales. Specifically, it may be a good indicator of the competitive pressures faced by company. Journalists should examine gross margin and compare it to past years. (Gross margin = gross profit/sales.)

The intermediate total of gross margin, which is calculated by dividing gross profit by sales, shows the relationship between sales and how much it costs to produce those sales. Specifically, it may be a good indicator of the competitive pressures faced by company. Journalists should examine gross margin and compare it to past years. (Gross margin = gross profit/sales.) Journalists should look at a company’s profit margin, which is found by dividing operating income by net sales. This figure, also called operating margin, shows how profitable a company is at performing what it calls its central operations. Are the company’s operations more or less profitable than the previous year? Is the company doing something to influence profit, or are outside factors involved? (Profit margin = operating income/net sales).

Journalists should look at a company’s profit margin, which is found by dividing operating income by net sales. This figure, also called operating margin, shows how profitable a company is at performing what it calls its central operations. Are the company’s operations more or less profitable than the previous year? Is the company doing something to influence profit, or are outside factors involved? (Profit margin = operating income/net sales). Journalists should be cautious about putting too much emphasis on earnings per share as a measure of a company’s performance. Companies sometimes use repurchases of shares to increase EPS by reducing the denominator of that measure.

Journalists should be cautious about putting too much emphasis on earnings per share as a measure of a company’s performance. Companies sometimes use repurchases of shares to increase EPS by reducing the denominator of that measure. Return on equity can be a good way to compare the profitability of a company vs. other companies in the same industry. ROE is found by dividing net income by average stockholders’ equity (ROE = net income/average stockholder’s equity).

Return on equity can be a good way to compare the profitability of a company vs. other companies in the same industry. ROE is found by dividing net income by average stockholders’ equity (ROE = net income/average stockholder’s equity).REFERENCES

The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). Accounting Research Bulletins, Inc. 1211 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10036.

Antle, Rick, and Stanley J. Garstka. Financial Accounting. Cincinnati: South-Western, 2002.

Atkins, Paul. “The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002: Goals, Content, and Status of Implementation.” Speech given before the International Financial Law Review, 25 March 2003. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Web site. www.sec.gov/news/speech/spch032503psa.htm. Accessed 29 July 2003.

Bannock, Graham. “The Bottom Line: Sir Bryan Carsberg on Creating Global Accounting Standards.” The Financial Regulator 7, no. 4 (March 2003): 22–29. Available on PriceWaterhouseCoopers’ Web site: www.pwcglobal.com. Accessed 17 July 2003.

Bryan-Low, Cassell. “Modest Digs, Tough Job for an Accounting Cop.” Wall Street Journal, 23 July 2003.

Burns, Judith. “Accounting Panel Provides Insights into its Workings.” Wall Street Journal, 29 July 2003.

Campos, Roel C. “Embracing International Business in the Post-Enron Era.” Speech given before the Centre for European Policy Studies in Brussels, Belgium, 11 June 2003. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Web site. www.sec.gov/news/speech/spch061103rcc.htm. Accessed 29 July 2003.

Choi, Frederick D. S., Carol Ann Frost, and Gary K. Meek. International Accounting. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2002.

“Commission Approves Rules Implementing Provisions of Sarbanes-Oxley Act, Accelerating Periodic Filings, and Other Measures.” 27 August 2002. http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2002–128.htm. Link valid as of 8 February 2004.

Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu. IFRS In Your Pocket. Hong Kong: Deloitte, Touche, Tohmatsu, 2003.

FASB. FASB Concepts Statements No. 5 and No. 6 and FASB Statements No. 5 and 130 are copyrighted by the Financial Accounting Standards Board, 401 Merritt 7, P.O. Box 5116, Norwalk, Connecticut 06856, U.S.A. Portions are reprinted with permission. Complete copies of these documents are available from the FASB.

Greene, Edward F., and Linda C. Quinn. “Building on the International Convergence of the Global Markets: A Model for Securities Law Reform.” Paper presented at the SEC Historical Society/U.S. SEC Major Issues Conference: Securities Regulation in the Global Internet Economy, Washington, D.C., 15 November 2001. Revised 27 December 2001.

International Accounting Standards Board. References. http://www.iasb.org. Link valid as of 8 February 2004.

Investors Responsibility Research Center. “IAS vs. GAAP: IS Fight Looming Between EU and U.S.” Corporate Governance Bulletin, August 2002.

Kieso, Donald E., Jerry J. Weygandt, and Terry D. Warfield. Intermediate Accounting. 10th ed. New York: Wiley, 2001.

Luesby, Jenny. “Accounting for Companies.” Chapter 10 of her The Word on Business. 155–73. London: FT/Prentice Hall, 2001.

Matlack, Carol, with John Rossant, David Fairlam, and Kerry Capell. “Europe’s Year of Nasty Surprises.” Business Week, 10 March 2003.

Nazareth, Annette L., Director of Market Regulation, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. “Remarks at the PLI Conference on International Securities Markets 2003.” Speech given in New York City, 9 May 2003. SEC Web site. www.sec.gov/news/speech/spch050903aln.htm. Accessed 29 July 2003.

Postelnicu, Andrei. “A Little Breathing Space: Sarbanes-Oxley Act.” Financial Times, 7 July 2003.

Quinn, Linda. “The SEC and International Reporting (Regulatory Infrastructure Covering Financial Markets).” The Citigroup International Journalists Seminar, 9 June 2003, New York.

Scherreik, Susan. “How Efficient Is That Company?” Business Week, 23 December 2002.

Tafara, Ethiopis. “Addressing International Concerns under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.” Remarks before the American Chamber of Commerce in Luxembourg, 10 June 2003. www.sec.gov/news/speech/spch061003et.htm. Accessed 29 July 2003.

Tergesen, Anne. “The Fine Print: How to Read Those Key Footnotes.” Business Week, 4 February 2002.

———. “The Fine Print: How to Spot Tax Tinkering,” Business Week, 20 May 2002.

———. “Cash-Flow Hocus-Pocus,” Business Week, 15 July 2002.

———. “Getting to the Bottom of a Company’s Debt,” Business Week, 14 October 2002.

Wall Street Journal. “Corporate Reform: The First Year,” special report, Wall Street Journal, 21–25 July 2003.

White, Gerald I., Ashwinpaul C. Sondhi, and Dov Fried. The Analysis and Use of Financial Statements, 3rd ed. New York: Wiley, 2003.

NOTES

1. In this chapter, we will discuss auditing only as it relates to the institutional context in which accounting takes place. Although often lumped together as the same thing, auditing is a separate discipline closely related but different from accounting. Auditing is best defined as “the process by which specialized accounting professionals (auditors) examine and verify the adequacy of a company’s financial and control systems and the accuracy of its financial records”: Frederick D.S. Choi, Carol Ann Frost, and Gary K. Meek, International Accounting, 4th ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2002), 1.

2. While the EU will require this of most companies by 2005, “publicly traded companies whose securities are admitted to trading on markets outside the EU and which, for that purpose, currently use internationally accepted standards (e.g. US standards)” may delay compliance until January 2007. Depannent of Trade and Industry, “UK Extends Use of International Accounting Standards,” news release, 17 July 2003, www.dti.gov.uk/cld/pressnotice170703.pdf; link valid as of February 2004.

3. The discussion of the nature of accounting follows, in certain instances, the structure set forth by Rick Antle and Stanley J. Garstka in Financial Accounting, which the authors have found to be the clearest exposition of the subject. See Rick Antle and Stanley J. Gartska, Financial Accounting (Cincinnati: South western, 2002), 3–19.

4. Antle and Garstka, Financial Accounting, 4.

6. Antle and Garstka use more purely economic concepts, including different definitions of financial value, wealth, and what they call “economic income” to discuss the measurement of an entity’s wealth and changes in that wealth (Antle and Garstka, Financial Accounting, 12–14). ln me interest of simplification and space, we focus on these concepts as accountants have modified them.

7. For a more technical discussion of comprehensive income of business enterprises, see FASB Statement of Concepts No. 6, Elements of Financial Statements, paragraphs 70–77, December 1985.

8. Antle and Garstka break out the three areas addressed by GAAP as “accounting valuation, recognition and disclosure.” The authors of this article prefer the term “measurement” to “accounting valuation.” Antle and Garstka, Financial Accounting, 16–17.

9. See FASB Concepts Statement No. 5, Recognition and Measurement in Financial Statements of Business Enterprises, paragraph 6, December 1984.

10. For a more technical discussion of the accrual method of accounting, see FASB Concepts Statement No. 6, paragraph 139.

11. For a more technical discussion of the balance sheet, see FASB Concepts Statement No. 1, Objectives of Financial Reporting by Business Enterprises, paragraph 41, November 1978.

12. See FASB Concepts Statement No. 6, paragraph 25. For further discussion of assets, see paragraphs 25–33.