THE OIL AND natural gas industries play a decisive role in the economic, social, and environmental development of countries with I deposits of either fuel. While the discovery of oil or gas is usually heralded as a windfall for a country’s economy, particularly a poor one, it can also be a double-edged sword. Economists term this phenomenon the “resource curse,” and it is often associated with worsening income distribution and a lack of development not only on the economic front but in the social and environmental realms as well. For journalists in developing countries covering the petroleum industry, it is vital to understand the “resource curse” and what can be done to counteract it. Some oil-exporting countries have managed to spread the benefits from oil to broad sectors of their populations, primarily through mechanisms of “good governance.” So there is nothing inevitable about the resource curse.

A WEAK RECORD

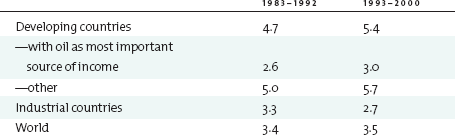

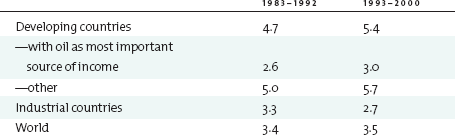

Historically, the petroleum industry has had a weak record in fostering development. Based on empirical data it appears that the more resources a country has, the worse its prospects for economic development. This was evident during the 1980s and 1990s, when oil-dependent developing countries posted average growth of between 2 and 2.5 percentage points less than developing countries that did not possess oil. Though the decline in real oil prices may explain part of this failure, similar results show up for resource-rich countries over a longer time frame (see table 22.1).1 There are several factors contributing to this seemingly paradoxical result.2

TABLE 22.1

REAL GDP GROWTH IN OIL-INTENSIVE COUNTRIES (%)

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2001.

Conflict. The existence of the often huge profits, or rents (defined as returns in excess of a “normal rate of return), arising from petroleum production gives rise to conflict, and not just between the governments and the oil companies that they rely upon to extract the resources. Local and national governments in oil-producing nations often fight over oil revenues. In Russia, for example, provincial governments have historically held up expansion of the oil industry because of their dissatisfaction with the share of federal oil revenues coming their way. In Nigeria, meanwhile, the conflict has been seen in the unrest of the Niger Delta, where the population claims oil money has been squandered by the federal government or has disappeared into foreign bank accounts. With this backdrop, the oil and gas activities have in many cases done more to stall development than to foster it.

Conflict. The existence of the often huge profits, or rents (defined as returns in excess of a “normal rate of return), arising from petroleum production gives rise to conflict, and not just between the governments and the oil companies that they rely upon to extract the resources. Local and national governments in oil-producing nations often fight over oil revenues. In Russia, for example, provincial governments have historically held up expansion of the oil industry because of their dissatisfaction with the share of federal oil revenues coming their way. In Nigeria, meanwhile, the conflict has been seen in the unrest of the Niger Delta, where the population claims oil money has been squandered by the federal government or has disappeared into foreign bank accounts. With this backdrop, the oil and gas activities have in many cases done more to stall development than to foster it. Rent seeking replaces entrepreneurship. In countries with oil and gas riches, the main commercial activity often becomes “how to rob the state” instead of how to create new wealth. Unlike other forms of enterprises, there are few direct spillovers from gas and oil production to other parts of the economy, other than through the profits generated. But the vast profits available in the oil and gas sector seem to bleed the entrepreneurial spirit of the local capitalist and merchant classes. This is nothing new, nor is it a phenomenon restricted to the oil and gas industry. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the pattern was seen in Spain following the huge inflow of gold from the new colonies in the Americas.

Rent seeking replaces entrepreneurship. In countries with oil and gas riches, the main commercial activity often becomes “how to rob the state” instead of how to create new wealth. Unlike other forms of enterprises, there are few direct spillovers from gas and oil production to other parts of the economy, other than through the profits generated. But the vast profits available in the oil and gas sector seem to bleed the entrepreneurial spirit of the local capitalist and merchant classes. This is nothing new, nor is it a phenomenon restricted to the oil and gas industry. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the pattern was seen in Spain following the huge inflow of gold from the new colonies in the Americas. Corruption and its consequences. While incentives in the private sector may be undermined and misdirected toward rent seeking rather than wealth creation, the adverse effects in the public sector are even greater. The large amount of easy wealth under the control of the government often leads to corruption, and companies are tempted to bribe government officials in order to get access to the resources at a price below the fair market value. While the country as a whole loses because bribery leads to a portfolio of damaging projects, the government officials gain. The corruption not only undermines good governance but fuels political and social unrest. When corrupt governments gain access to the large incomes generated by oil and gas, they often repress human rights to ensure that the revenues keep flowing without the interference of social or political unrest.

Corruption and its consequences. While incentives in the private sector may be undermined and misdirected toward rent seeking rather than wealth creation, the adverse effects in the public sector are even greater. The large amount of easy wealth under the control of the government often leads to corruption, and companies are tempted to bribe government officials in order to get access to the resources at a price below the fair market value. While the country as a whole loses because bribery leads to a portfolio of damaging projects, the government officials gain. The corruption not only undermines good governance but fuels political and social unrest. When corrupt governments gain access to the large incomes generated by oil and gas, they often repress human rights to ensure that the revenues keep flowing without the interference of social or political unrest.

SIDEBAR

The term “rent” is used by economists to designate income in excess of total expenses, including “capital recovery.” Another term for rent is “economic income.” Economic income differs from the business-accounting concept of income in the way payments for the use of investment goods are treated. In business accounting, only the original outlay for investment goods is deducted, or “expensed,” as depreciation over time. To calculate rent or economic income, a charge for the “carrying” of using the investment goods is deducted as well.

The prospective flow of rent determines the value of an enterprise in excess of the value of the investment goods it owns. The higher the expected future stream of rent, the higher the enterprise’s value is today.

If an enterprise is earning rents in a particular line of business, we would expect that other investors would be attracted to enter and that in the long run, competition would bid prices down and costs up until the rents disappear and each enterprise is earning only its competitive cost of capital.

Economists identify several situations in which this long-run process does not work and in which rents continue to accrue. Land and resource rents arise when a critical factor of production cannot be reproduced. The price of land or resource ownership reflects the discounted value of these rents. The potential for technical monopoly rents arises when, at efficient scale, one firm dominates the market and can drive prices above costs unless regulated. Political rent seeking occurs when enterprises use political influence to find institutional benefits, such as franchises, subsidies, tariffs, or quotas, which appropriate revenue but do not add value.

In the nineteenth century, the classical economist David Ricardo elegantly worked out how to think about rent when applying the concept to land. The cost of producing a particular good, according to Ricardo’s theorem, varies with the quality of land used to produce the good: the higher the land’s quality, the cheaper the cost of production. However, irrespective of the cost of production, all goods of a type have the same market price. Therefore, owners of higher-quality land can keep a larger share (the “residual”) of a good’s price than owners of lower-quality land. This “residual” is equivalent to the rent that a landowner can charge.

The same analysis applies to oil production, where the term “rent” is used extensively. Oil prices are determined in the international market. However, the cost of extracting the oil differs markedly from region to another. Countries with low production costs (mainly in the Arabian Gulf) can extract a much higher “rent” from each oil barrel than those with higher production costs.

The above theory of rent applies to a factor of production (for example, land or oil) that is productive but not yet produced. This raises the question: What is the rent on factors of production that have already been produced but that themselves can be further used for production of other goods and services? The best example of this is an investment good such as machinery. Calculating rent on an investment good requires three steps. First, establish free cash flow, which is defined as the difference between revenue generated from the investment good, on the one hand, and operating expenses and required additional investment, on the other. Second, calculate profit, which is the difference between the free cash flow and the interest the asset’s owner pays on the funding that he or she had to raise to pay for the asset. Third, economic profit, thus calculated, is defined as rent.

The phrase “rent seeking” is also used in another context: to describe efforts to acquire wealth without adding value. Market imperfections—including the absence of a well-structured property-rights system and a lack of efficient markets—can be abused by rent seekers to extract noneconomic profit. For example, rent seekers could use political influence to change subsidies, tariffs, franchises, regulatory measures, and the like.

The Dutch disease. Holland provides one example of the negative financial fallout the energy industry can unleash. In the late 1970s, the country saw a dramatic jump in its state income from the natural gas sector, which improved its financial position. As energy-related earnings flowed in, the currency strengthened, and the competitiveness of the sectors not involved in energy production eroded, causing a “crowding out” of industries not linked to the gas sector. Nigeria had a similar experience when the overvalued currency in the 1970s and 1980s crowded out the local agricultural production. The problem is particularly serious in developing countries, however: the overvalued currency impedes the creation of the new industries and jobs which are essential for successful development.

The Dutch disease. Holland provides one example of the negative financial fallout the energy industry can unleash. In the late 1970s, the country saw a dramatic jump in its state income from the natural gas sector, which improved its financial position. As energy-related earnings flowed in, the currency strengthened, and the competitiveness of the sectors not involved in energy production eroded, causing a “crowding out” of industries not linked to the gas sector. Nigeria had a similar experience when the overvalued currency in the 1970s and 1980s crowded out the local agricultural production. The problem is particularly serious in developing countries, however: the overvalued currency impedes the creation of the new industries and jobs which are essential for successful development. Instability. Oil prices have exhibited enormous instability (and the same is true of the prices of other commodities), and while both developed and less-developed countries have difficulties managing the consequences of the resulting instability of revenues, the problems are particularly acute for developing countries. Typically, in good times, foreign lenders encourage them to borrow, and, given their vast needs, the countries do so with alacrity. But because of their limited capacities, much of the money is invested poorly. Then, when oil prices fall, not only do lenders stop lending, they start demanding their money back, forcing the countries into crisis.

Instability. Oil prices have exhibited enormous instability (and the same is true of the prices of other commodities), and while both developed and less-developed countries have difficulties managing the consequences of the resulting instability of revenues, the problems are particularly acute for developing countries. Typically, in good times, foreign lenders encourage them to borrow, and, given their vast needs, the countries do so with alacrity. But because of their limited capacities, much of the money is invested poorly. Then, when oil prices fall, not only do lenders stop lending, they start demanding their money back, forcing the countries into crisis.What is critical for any country is the difference between the price it receives for the oil and the cost of extraction. The price it receives is the international price (say the price in Europe or America), less the cost of transportation. A country with low extraction costs and low transportation costs has high rents, and a 10 percent reduction in the price accordingly has a relatively small effect on these rents compared to a country with high extraction costs and/or high transportation costs. In the aftermath of the East Asian crisis in the late 1990s, oil prices fell so low that rents were almost eliminated in some large producers, such as Russia.

GLOBAL AND LOCAL ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS

Oil and gas production has, in a number of well-documented cases in such places as Nigeria, Alaska, and Argentina, had an adverse effect on the local environment. That so much of the cost is often borne by local communities, including indigenous people, and so much of the revenue goes to the national governments is a major source of dissatisfaction. While this is true for most natural resources, oil and to a lessser extent gas have, in addition, adverse global environmental effects as a carbon-based fuel that gives off significant emissions of greenhouse gases, with the most important of these being carbon dioxide.

Some petroleum-exporting countries in the developing world such as Malaysia and Oman have not encountered the same negative effects that were described above. OECD countries like Canada and Norway have largely managed to successfully incorporate a large petroleum sector into their economies. But that being said, the overall picture for developing countries is nevertheless rather bleak. The question that arises, then, is what governments and companies can do to repair or avoid these negative consequences and encourage the more positive aspects of oil and gas production. Ideally, the extra revenues from hydrocarbons could improve living standards for the broader population, while still assuring that the interests of groups most immediately affected by the industry are met.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE OIL AND GAS INDUSTRY

Before a discussion of such positive strategies is possible, however, it is important to understand some of the key developments in the industry and the outlook for the globe’s use of oil and gas. Oil and gas are expected to remain the dominant fuels worldwide for the next thirty years. Around 62 percent of the globe’s energy demand is currently supplied by hydrocarbons, a percentage that is expected to increase to about 67 percent by 2030 if demand continues to grow at the pace seen in the last decade. This increase stems from the rising use of the clean-burning natural gas, which is expected to grow from 23 percent of world energy supply to 28 percent, while oil’s share is set to remain more or less unchanged.3

There are two principle reasons for the world’s continued reliance on oil and gas. First, there are currently no alternatives to these fuels in transportation. Although a number of the world’s major energy companies are pushing to advance research on hydrogen-driven fuel cells, this is unlikely to have a significant impact on petroleum demand over the next thirty years.4 Second, natural gas is likely to continue its rapid ascent as the world’s favorite fuel because of its advantages in generating electricity. Among the carbons, gas is the fuel with the lowest emissions,5 and it yields the lowest costs per kilowatt hour of electricity produced, elements that have led to its characterization as the preferred “transitional fuel” or the “bridge to the energy future.”6 If the present concerns about global warming continue, there will be strong pressure for economies like China and India to switch from coal-based electricity to the less-polluting natural gas. Natural gas can also be used to produce hydrogen, so demand may get a further boost as hydrogen use develops.

Figures from the International Energy Agency show that even if the world pursues a more aggressive energy-saving agenda and especially increases its use of wind and solar power—renewable sources currently account for a paltry 3 percent of all global commercial energy—it would be a long time before there was a significant effect on the relative position of the oil and gas industries.

Oil and gas are also likely to remain dominant because there is more than enough of both fuels to meet expected demand for the foreseeable future. Frequently, claims are made that the world is running out of hydrocarbons, but there is little indication that the globe lacks physical resources of such fuels. The ratio of reserves to production has increased for gas and slightly decreased for oil over the last decades. The problem is more the location of the reserves—the majority are found or could be found in the Middle East, where political instability can be a hurdle to production. Gas reserves are also found at great distances from the places they are actually consumed, increasing costs of transportation. (But of course, there is no assurance that reserves will continue to be discovered.)

In addition, oil and gas have been and are likely to remain a strategic commodity, or a commodity that is so vital to the operation of the world economy that it is prone to strong political interference from both the demand and supply sides.7 Three examples highlight this point.

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, in existence for more than forty years, aims to adjust oil supplies in line with world demand to keep prices elevated. OPEC was also once used as a political instrument in the aftermath of the 1973 Middle East war,8 but the organization’s present policy is to stay away from such action.

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, in existence for more than forty years, aims to adjust oil supplies in line with world demand to keep prices elevated. OPEC was also once used as a political instrument in the aftermath of the 1973 Middle East war,8 but the organization’s present policy is to stay away from such action. A central element of global economic development over the last fifty years has been unfettered access to relatively cheap and predictable flows of oil. The United States, as the world’s main superpower, has an overriding interest in securing a stable flow of oil at such terms. Many allege that oil played a role in the country’s decision to go to war in Iraq in both 1991 and 2003, while others emphasize more ideological explanations.

A central element of global economic development over the last fifty years has been unfettered access to relatively cheap and predictable flows of oil. The United States, as the world’s main superpower, has an overriding interest in securing a stable flow of oil at such terms. Many allege that oil played a role in the country’s decision to go to war in Iraq in both 1991 and 2003, while others emphasize more ideological explanations. International natural-gas projects are often a mixture of politics and economics since they cross national borders, requiring the cooperation and approval of various governments to become a reality. One example is the difficulty of sending gas from the Middle East and Iran to India because the planned pipeline must cross Pakistan, a country with whom India has strained relations. Another was the construction of additional pipelines taking gas from Russia to Western Europe during the late years of the Cold War in the 1980s, despite the determined opposition of the U.S. government.

International natural-gas projects are often a mixture of politics and economics since they cross national borders, requiring the cooperation and approval of various governments to become a reality. One example is the difficulty of sending gas from the Middle East and Iran to India because the planned pipeline must cross Pakistan, a country with whom India has strained relations. Another was the construction of additional pipelines taking gas from Russia to Western Europe during the late years of the Cold War in the 1980s, despite the determined opposition of the U.S. government.Within the oil and gas industry, it is also important to understand the various players. A handful of private multinational oil companies currently dominate the international oil industry, companies that are known as super-majors and that include ExxonMobil, BP, the Royal Dutch/Shell Group and ChevronTexaco. Their exploration success over the recent years has been weak, and today some of these companies have developed strong interests in energy sectors other than oil, such as natural gas and, in some cases, renewable energy sources.

In spite of the dominance of the super-majors, state-owned oil companies are still powerful players in the industry, controlling a large chunk of the world’s oil production. As of 2001, 60 percent of oil output was in the hands of state oil firms like Aramco in Saudi Arabia, the Kuwaiti Oil Company, the Nigerian National Oil Company, and Sonatrach of Algeria. Some countries, like Mexico, have constitutional provisions that do not allow for privatization of oil-producing assets. There is also a large group of regional private companies, whose operations are smaller in scope and who compete with the super-majors in specific niches within various markets.

Since the mid-1980s, more of the world has been opened up for the international oil companies, while there has been a growing tendency toward privatization in the oil industry.9 This trend was partly a response to the failing performances of a number of state oil companies. Some governments, facing severe budget constraints, could not invest adequately in the sector. In part, this often reflected IMF-imposed conditions that treated all government expenditures equally, with no distinction between spending for investment purposes and spending for consumption reasons. There was also an ideological component: U.S. President Ronald Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher introduced the belief that the state should stay out of any kind of productive enterprises. This policy was at least initially supported by strong multilateral organizations like the World Bank.10

The trend toward privatization has new consequences for the way the industry traditionally has operated in places where governments control the level of production. If OPEC wants to maintain its power over the world oil market and world oil prices, it must retain the ability to control the supply levels of member states, which currently coordinate cutbacks in supplies when prices drop and supply increases when prices jump. So far, cooperation has not been a problem because production in most OPEC nations is controlled by the state, either directly or through state oil companies. But the ability to control supply may be more problematic as international oil companies strengthen their presence in the region and decisions about production levels become more investment driven. Private investors are not likely to warm to large swings in the utilization of their capital investments, even if the ultimate aim of these shifts is higher prices. This development is only in its infancy, and it is difficult to predict what will happen, especially in the Middle East. But if the trend becomes dominant it will change the way the oil industry operates.

In recent years, new powerful national firms run by the private sector have also appeared on the oil scene, such as a number of Russian companies that have opened up for closer cooperation with western companies. But their long-term fate still seems to be closely linked the Russian government, which wants to maintain strong control of Russian resources.

Finally, service companies such as the oil-technology firms Schlumberger and Halliburton are playing an increased role in the industry. Both private and public oil companies are increasingly using these types of firms to carry out complicated technological tasks. Previously, this work was given to multinational companies, which in turn subcontracted with the service companies to do the job. A possible long-term trend thus appears to be the weakening of the middlemen (the multinationals) and strengthening of the role of the service companies. This trend is today seen in Russia and parts of the Middle East.

CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

There has been extensive criticism of the industry in recent years—from oil spills that pollute the ocean (such as the Valdez spill in Alaska) to the greenhouse gases the pollute the atmosphere to involvement in abuses of human rights (as in Nigeria). During the 1980s and 1990s, nongovernmental organizations began to ask fundamental questions about the industry and the human-rights conditions in the countries in which oil companies operated. They raised concerns about the way oil operations were carried out on the ground, the impact on indigenous people of exploration and production, and the industry’s position on greenhouse gases. They also questioned the conditions of the workers of the oil industry, as well as their subcontractors, in the producing countries. As the NGOs raised more and more doubts, shareholders also became restless and the share values of some companies started to come under pressure.

The corporate sector responded to these concerns, and by the mid-1990s, oil companies could no longer follow their old strategies. Shell led the way in changing its ways of operating after it was badly shaken by two incidents: the intense opposition from both consumer groups and governments to its scuttling one of its oil rigs, Brent Spar in the North Sea, and the execution of author Ken Saro Wiwa in Nigeria, which in world opinion was linked to Shell’s dominant position in that country. In response, Shell developed a more aggressive policy of “corporate social responsibility,” which has subsequently been copied or used as the inspiration for a number of other companies’ policies. Companies attempted to deal with most or all of the questions raised by the NGOs and society at large, and while some policy statements were superficial, other firms took the issues seriously and tried to change course.11

The movement toward CSR was not only a result of NGO pressure. A number of the major international companies had come to believe that the questions about sustainable development and the global environment warranted a more systematic response.12 Some of the major oil companies published goals for the reduction of greenhouse gases, and some firms began providing audited environmental and social balance sheets in addition to their financial balance sheets. BP instituted an internal trading system in a bid to reduce its emissions for greenhouse gases, and a number of oil companies are aggressively pursuing research and development into hydrogen-based fuel cells. Companies have also started to invest heavily in alternative energy sources such as wind power.

WHAT CAN BE DONE TO BRING ABOUT SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT?

In light of this recent history, there appears to be a historic opening for the global oil industry to increase its focus on sustainable development to ensure that the industry contributes more to the growth of the developing countries and that it does less to harm the environment. That at least part of the industry and some governments, regardless of their reasons, are more willing to adhere to the principles of sustainable development is to be welcomed. There are also a number of new actors in the industry that may represent a more diverse range of viewpoints than the monolithic attitudes that have characterized the industry in the past.

There are three strategies or actions that could help build a more sustainable petroleum sector. The first and most important is related to improved governance. The countries that have succeeded in overcoming the resource curse all have good records of governance. Given this, it is tempting to relabel the “resource curse” the “governance curse.” One way to improve governance is to ensure better transparency in the spending of oil revenues, whether at the state or regional level. Transparency allows effective oversight by regulators and the public in large. It is, as such, an important way to fight entrenched corruption and helps increase the general quality of governance in a society. In countries where one root cause of the resource curse is the erratic and secretive spending of petroleum revenues by corrupt government officials, an initial step can be simply to inform the public of how much income the country earns from the activity. Incredibly, there are still a number of states in which this is not the case and in which large amounts of revenues are hidden from public scrutiny, although there has been progress recently.13 There are a number of global initiatives to combat corruption that will contribute to improving transparency in the oil and gas sector.14

Another step that would guarantee increased transparency and better governance is the establishment of petroleum-revenue stabilization funds or petroleum funds for future generations. Such funds are found in many territories and countries, such as Alaska, Kuwait, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Chad, and Norway. These funds, which store away a certain amount of oil revenues, attempt to deal with the swings in oil income and the fact that the present generation is consuming an exhaustible resource at the expense of future generations. Successful funds can also promote sustainable development by shifting petroleum resources, which will eventually run out, into new assets so that growth can be sustained even when there are no longer oil revenues. One such a fund has been set up by the government of Chad in cooperation with the World Bank to channel income from the Chad/Cameroon oil pipeline into a number of specific social fields like education and health.15

The Norwegian Petroleum Fund has been described as a successful example of a future-generation fund. All net petroleum-related income from the production of oil and natural gas in Norway flows into this special fund, which has reached a level equal to about 60 percent of gross domestic product. Of this money, 60 percent is placed in bonds and 40 percent in equities—all in non-Norwegian assets. Each year the equivalent of 4 percent of the fund’s value is withdrawn, a level that is the expected long-term real rate of return on these assets. This arrangement ensures that the value of the fund remains unchanged if there are no new deposits into the fund while diversifying the risk of the holdings. It is, in effect, creating an endowment for the country.

Such funds are not a panacea. What parliaments and presidents can create, parliaments and presidents can undo. There are no guarantees that these funds, often created in periods of plenty, will continue to exist when the going gets tough. The survival of the funds ultimately depends on the strength of the political system backing it up and the ability to stick to often-difficult decisions when circumstances change. Still, these funds do force governments to be more transparent in their handling of petroleum revenues, and in this way, they encourage strengthened governance in petroleum-producing states. For many who see a basic lack of governance as the key problem in resource-rich countries, this is a good enough reason to support resource-based funds.

A second strategy to encourage sustainable development is to force the oil industry to follow the principles of “best international practice” when operating in developing and emerging economies. In many cases this simply means that they follow the principles the industry itself has formulated with respect to carrying out environmental-impact assessments, treating workers fairly, dealing with indigenous populations, and not paying bribes. Host governments should also follow such principles. Sometimes governments try to gain a leg up in the attraction of foreign investment by lowering environmental standards. In these circumstances, the burden falls on serious companies to refuse to invest.

A third action that would support environmentally sustainable development is an increased use of natural gas. Natural gas has both local and global environmental advantages over other fossil fuels, and it is the most cost-efficient way of bringing electricity to much of the quarter of the world’s population currently without it. (In the past, natural gas was sometimes simply wasted, flared off, rather than captured and transported to where it could be used.) A move toward gas on a global scale is already under way, but major entities like the World Bank and the European Union could help to foster this trend.

CONCLUSION

Historically, the oil sector has seemed to have made less of a contribution in promoting sustainable development that it could have. If the sector wants to change this record and tackle some of the more pressing problems, its most important tasks involve improving governance by ensuring that petroleum revenues are more transparent and that corruption is contained. The industry should follow international “best practices” in the execution of projects, and shift more toward natural gas. If governments, industries, multilateral agencies, and civil societies work together, such actions can be implemented, and the oil and gas industry would make a more significant contribution toward sustainable development.

TIPS FOR REPORTERS

How are oil companies living up to their own stated policies and best practices in the field of sustainable development?

How are oil companies living up to their own stated policies and best practices in the field of sustainable development? What are the responses from the financial markets to the strategies of the major companies toward achieving sustainable development?

What are the responses from the financial markets to the strategies of the major companies toward achieving sustainable development? Is the trend toward privatizations continuing? What is driving the push for privatization? Inefficiency on the part of the state run industry? Lack of capital to investment in the state run industry? Ideology? Is the lack of investment caused in part by faulty accounting, which penalizes public investment compared to private investment? What role are international agencies like the IMF and the World Bank playing in the push for privatization?

Is the trend toward privatizations continuing? What is driving the push for privatization? Inefficiency on the part of the state run industry? Lack of capital to investment in the state run industry? Ideology? Is the lack of investment caused in part by faulty accounting, which penalizes public investment compared to private investment? What role are international agencies like the IMF and the World Bank playing in the push for privatization? Is corruption in the industry being contained? Is governance improving and transparency increasing?

Is corruption in the industry being contained? Is governance improving and transparency increasing? What is the cost of oil extraction and transport in the country? At what price in the international markets will production become unprofitable?

What is the cost of oil extraction and transport in the country? At what price in the international markets will production become unprofitable? Are stabilization funds solidly anchored, or are they likely to unravel when the price of oil drops?

Are stabilization funds solidly anchored, or are they likely to unravel when the price of oil drops? Reporters should watch out for decisive technological changes in the hydrogen business, particularly in the form of dramatic decreases in storage costs, in the production costs of fuel cells, and, most important, in governments’ active support of the industry.

Reporters should watch out for decisive technological changes in the hydrogen business, particularly in the form of dramatic decreases in storage costs, in the production costs of fuel cells, and, most important, in governments’ active support of the industry. Is natural gas increasing its market share as expected? Reporters need to be on the look out for technological changes like the direct conversion of natural gas for air conditioning and small-scale use of natural gas for local electricity and heat generation, which will increase the local use of gas.

Is natural gas increasing its market share as expected? Reporters need to be on the look out for technological changes like the direct conversion of natural gas for air conditioning and small-scale use of natural gas for local electricity and heat generation, which will increase the local use of gas. Are there any signs of an increase or decrease in OPEC’s power, particularly as expressed through its market share? Is the influence of the international oil companies in investment and production decisions in OPEC countries increasing?

Are there any signs of an increase or decrease in OPEC’s power, particularly as expressed through its market share? Is the influence of the international oil companies in investment and production decisions in OPEC countries increasing? Reporters should be on the look out for the development of substitutes to petroleum products. Coal could become a formidable competitor and capture market share from other fuels, especially natural gas, if a way is found to decrease greenhouse-gas emissions from coal combustion. Also, closely monitor efforts at conservation and technological change that reduce the demand for energy.

Reporters should be on the look out for the development of substitutes to petroleum products. Coal could become a formidable competitor and capture market share from other fuels, especially natural gas, if a way is found to decrease greenhouse-gas emissions from coal combustion. Also, closely monitor efforts at conservation and technological change that reduce the demand for energy. Increasing concerns about global warming may, over the next few years, lead to further efforts to reduce the energy intensity of economic growth and to internalize the full economic costs of the production and use of different fuels. This could have major effects on the price of gas and oil compared to other energy carriers.

Increasing concerns about global warming may, over the next few years, lead to further efforts to reduce the energy intensity of economic growth and to internalize the full economic costs of the production and use of different fuels. This could have major effects on the price of gas and oil compared to other energy carriers.LINKS FOR MORE INFORMATION

(with thanks to Jean-Francois Seznec)

2. The International Energy Agency, which has basic information about the world’s energy scene. www.iea.org.

7. Homepage of the Petroleum Finance Ecompany, a consulting company based in Washington, D.C. www.pfcenergy.com.

NOTES

This piece was written when I was affiliated with the Stern School of Business, New York University during the academic year 2002/2003. All points of view expressed are my own and do not reflect in any way the views of my employer Hydro.

1. See for example Jeffrey D. Sachs and Andrew M. Warner, Natural Resource Abundance and Economic Growth: Leading Issues in Economic Development, NBER Working Paper no. 5398 (1995) and (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

2. For an overview of the issues subsumed under the heading “resource curse” and petroleum funds, see IMF, “Stabilization and Savings Funds For Nonrenewable Resources: Experience and Fiscal Policy Implications,” Occasional Paper no. 205, (Washington D.C.: IMF, 2001).

4. Hydrogen may indeed experience technical breakthroughs during this period, but because of the long lifetime of most capital assets including transport infrastructure like gas stations, the effects on the demand for other fuels will be modest.

5. In primary combustion, one kilowatt hour produced from natural gas gives rise to about half of the greenhouse-gas emissions of oil. Adopting a “life-cycle” perspective where leakage of greenhouse gases from the gas chain are included, the difference is still around one-fourth.

6. Cf. statement made by Lester Brown et al., State of the World (New York: W. W. Norton, 1991).

7. Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest For Oil, Money And Power(New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991), gives a comprehensive overview of the history of the oil industry and how a combination of economics and politics historically has influenced the dynamic of the industry

8. It was OAPEC (a subgroup of OPEC) that carried out the boycott.

9. For a critical overview of this trend of privatizations, see P. Stevens “The Practical Record and Prospects of Privatization Programmes in the Arab World,” in Economic and Political Liberalisation in the Middle East, ed. T. Niblock and E. Murphy (London: British Academic Press, 1992), 114–31.

10. The bank today has a more sophisticated appreciation of the role of the state; cf. the World Bank, “The State in a Changing World,” World Development Report (1997), which advocates a state that plays a “catalytic, facilitating role, encouraging and complementing the activities of private businesses and individuals” (iii).

11. The question at issue is the well-known conflict between shareholder and stakeholder value. How meaningful is a policy of CSR when the companies have a fiduciary duty towards their shareholders that takes precedence over all other interests? At the very least, a company’s management should deal with situations threatening to destroy shareholder value, such as major environmental or public relations disasters, in the same way it would handle an effort to increase sales and/or margins.

12. The creation in 1991 of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, a coalition of 165 international companies “united by a shared commitment to sustainable development via the three pillars of economic growth, ecological balance and social progress” was one such response.

13. The agreement in London in June 2003, under the aegis of “The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative,” where a number of oil-producing states pledged to make public their income from the oil sector, is a promising first step toward achieving a higher degree of transparency and hence strengthening governance in the petroleum sector. This agreement had the full support of the international oil industry.

14. Transparency International is the only international organization devoted to combating corruption. It has eighty-five independent chapters around the globe and focuses on prevention and reforming systems rather than on individual cases. See www.transparency.org.

Conflict. The existence of the often huge profits, or rents (defined as returns in excess of a “normal rate of return), arising from petroleum production gives rise to conflict, and not just between the governments and the oil companies that they rely upon to extract the resources. Local and national governments in oil-producing nations often fight over oil revenues. In Russia, for example, provincial governments have historically held up expansion of the oil industry because of their dissatisfaction with the share of federal oil revenues coming their way. In Nigeria, meanwhile, the conflict has been seen in the unrest of the Niger Delta, where the population claims oil money has been squandered by the federal government or has disappeared into foreign bank accounts. With this backdrop, the oil and gas activities have in many cases done more to stall development than to foster it.

Conflict. The existence of the often huge profits, or rents (defined as returns in excess of a “normal rate of return), arising from petroleum production gives rise to conflict, and not just between the governments and the oil companies that they rely upon to extract the resources. Local and national governments in oil-producing nations often fight over oil revenues. In Russia, for example, provincial governments have historically held up expansion of the oil industry because of their dissatisfaction with the share of federal oil revenues coming their way. In Nigeria, meanwhile, the conflict has been seen in the unrest of the Niger Delta, where the population claims oil money has been squandered by the federal government or has disappeared into foreign bank accounts. With this backdrop, the oil and gas activities have in many cases done more to stall development than to foster it. Rent seeking replaces entrepreneurship. In countries with oil and gas riches, the main commercial activity often becomes “how to rob the state” instead of how to create new wealth. Unlike other forms of enterprises, there are few direct spillovers from gas and oil production to other parts of the economy, other than through the profits generated. But the vast profits available in the oil and gas sector seem to bleed the entrepreneurial spirit of the local capitalist and merchant classes. This is nothing new, nor is it a phenomenon restricted to the oil and gas industry. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the pattern was seen in Spain following the huge inflow of gold from the new colonies in the Americas.

Rent seeking replaces entrepreneurship. In countries with oil and gas riches, the main commercial activity often becomes “how to rob the state” instead of how to create new wealth. Unlike other forms of enterprises, there are few direct spillovers from gas and oil production to other parts of the economy, other than through the profits generated. But the vast profits available in the oil and gas sector seem to bleed the entrepreneurial spirit of the local capitalist and merchant classes. This is nothing new, nor is it a phenomenon restricted to the oil and gas industry. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the pattern was seen in Spain following the huge inflow of gold from the new colonies in the Americas. Corruption and its consequences. While incentives in the private sector may be undermined and misdirected toward rent seeking rather than wealth creation, the adverse effects in the public sector are even greater. The large amount of easy wealth under the control of the government often leads to corruption, and companies are tempted to bribe government officials in order to get access to the resources at a price below the fair market value. While the country as a whole loses because bribery leads to a portfolio of damaging projects, the government officials gain. The corruption not only undermines good governance but fuels political and social unrest. When corrupt governments gain access to the large incomes generated by oil and gas, they often repress human rights to ensure that the revenues keep flowing without the interference of social or political unrest.

Corruption and its consequences. While incentives in the private sector may be undermined and misdirected toward rent seeking rather than wealth creation, the adverse effects in the public sector are even greater. The large amount of easy wealth under the control of the government often leads to corruption, and companies are tempted to bribe government officials in order to get access to the resources at a price below the fair market value. While the country as a whole loses because bribery leads to a portfolio of damaging projects, the government officials gain. The corruption not only undermines good governance but fuels political and social unrest. When corrupt governments gain access to the large incomes generated by oil and gas, they often repress human rights to ensure that the revenues keep flowing without the interference of social or political unrest. The Dutch disease. Holland provides one example of the negative financial fallout the energy industry can unleash. In the late 1970s, the country saw a dramatic jump in its state income from the natural gas sector, which improved its financial position. As energy-related earnings flowed in, the currency strengthened, and the competitiveness of the sectors not involved in energy production eroded, causing a “crowding out” of industries not linked to the gas sector. Nigeria had a similar experience when the overvalued currency in the 1970s and 1980s crowded out the local agricultural production. The problem is particularly serious in developing countries, however: the overvalued currency impedes the creation of the new industries and jobs which are essential for successful development.

The Dutch disease. Holland provides one example of the negative financial fallout the energy industry can unleash. In the late 1970s, the country saw a dramatic jump in its state income from the natural gas sector, which improved its financial position. As energy-related earnings flowed in, the currency strengthened, and the competitiveness of the sectors not involved in energy production eroded, causing a “crowding out” of industries not linked to the gas sector. Nigeria had a similar experience when the overvalued currency in the 1970s and 1980s crowded out the local agricultural production. The problem is particularly serious in developing countries, however: the overvalued currency impedes the creation of the new industries and jobs which are essential for successful development. Instability. Oil prices have exhibited enormous instability (and the same is true of the prices of other commodities), and while both developed and less-developed countries have difficulties managing the consequences of the resulting instability of revenues, the problems are particularly acute for developing countries. Typically, in good times, foreign lenders encourage them to borrow, and, given their vast needs, the countries do so with alacrity. But because of their limited capacities, much of the money is invested poorly. Then, when oil prices fall, not only do lenders stop lending, they start demanding their money back, forcing the countries into crisis.

Instability. Oil prices have exhibited enormous instability (and the same is true of the prices of other commodities), and while both developed and less-developed countries have difficulties managing the consequences of the resulting instability of revenues, the problems are particularly acute for developing countries. Typically, in good times, foreign lenders encourage them to borrow, and, given their vast needs, the countries do so with alacrity. But because of their limited capacities, much of the money is invested poorly. Then, when oil prices fall, not only do lenders stop lending, they start demanding their money back, forcing the countries into crisis. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, in existence for more than forty years, aims to adjust oil supplies in line with world demand to keep prices elevated. OPEC was also once used as a political instrument in the aftermath of the 1973 Middle East war,8 but the organization’s present policy is to stay away from such action.

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, in existence for more than forty years, aims to adjust oil supplies in line with world demand to keep prices elevated. OPEC was also once used as a political instrument in the aftermath of the 1973 Middle East war,8 but the organization’s present policy is to stay away from such action. A central element of global economic development over the last fifty years has been unfettered access to relatively cheap and predictable flows of oil. The United States, as the world’s main superpower, has an overriding interest in securing a stable flow of oil at such terms. Many allege that oil played a role in the country’s decision to go to war in Iraq in both 1991 and 2003, while others emphasize more ideological explanations.

A central element of global economic development over the last fifty years has been unfettered access to relatively cheap and predictable flows of oil. The United States, as the world’s main superpower, has an overriding interest in securing a stable flow of oil at such terms. Many allege that oil played a role in the country’s decision to go to war in Iraq in both 1991 and 2003, while others emphasize more ideological explanations. International natural-gas projects are often a mixture of politics and economics since they cross national borders, requiring the cooperation and approval of various governments to become a reality. One example is the difficulty of sending gas from the Middle East and Iran to India because the planned pipeline must cross Pakistan, a country with whom India has strained relations. Another was the construction of additional pipelines taking gas from Russia to Western Europe during the late years of the Cold War in the 1980s, despite the determined opposition of the U.S. government.

International natural-gas projects are often a mixture of politics and economics since they cross national borders, requiring the cooperation and approval of various governments to become a reality. One example is the difficulty of sending gas from the Middle East and Iran to India because the planned pipeline must cross Pakistan, a country with whom India has strained relations. Another was the construction of additional pipelines taking gas from Russia to Western Europe during the late years of the Cold War in the 1980s, despite the determined opposition of the U.S. government. How are oil companies living up to their own stated policies and best practices in the field of sustainable development?

How are oil companies living up to their own stated policies and best practices in the field of sustainable development? What are the responses from the financial markets to the strategies of the major companies toward achieving sustainable development?

What are the responses from the financial markets to the strategies of the major companies toward achieving sustainable development? Is the trend toward privatizations continuing? What is driving the push for privatization? Inefficiency on the part of the state run industry? Lack of capital to investment in the state run industry? Ideology? Is the lack of investment caused in part by faulty accounting, which penalizes public investment compared to private investment? What role are international agencies like the IMF and the World Bank playing in the push for privatization?

Is the trend toward privatizations continuing? What is driving the push for privatization? Inefficiency on the part of the state run industry? Lack of capital to investment in the state run industry? Ideology? Is the lack of investment caused in part by faulty accounting, which penalizes public investment compared to private investment? What role are international agencies like the IMF and the World Bank playing in the push for privatization? Is corruption in the industry being contained? Is governance improving and transparency increasing?

Is corruption in the industry being contained? Is governance improving and transparency increasing? What is the cost of oil extraction and transport in the country? At what price in the international markets will production become unprofitable?

What is the cost of oil extraction and transport in the country? At what price in the international markets will production become unprofitable? Are stabilization funds solidly anchored, or are they likely to unravel when the price of oil drops?

Are stabilization funds solidly anchored, or are they likely to unravel when the price of oil drops? Reporters should watch out for decisive technological changes in the hydrogen business, particularly in the form of dramatic decreases in storage costs, in the production costs of fuel cells, and, most important, in governments’ active support of the industry.

Reporters should watch out for decisive technological changes in the hydrogen business, particularly in the form of dramatic decreases in storage costs, in the production costs of fuel cells, and, most important, in governments’ active support of the industry. Is natural gas increasing its market share as expected? Reporters need to be on the look out for technological changes like the direct conversion of natural gas for air conditioning and small-scale use of natural gas for local electricity and heat generation, which will increase the local use of gas.

Is natural gas increasing its market share as expected? Reporters need to be on the look out for technological changes like the direct conversion of natural gas for air conditioning and small-scale use of natural gas for local electricity and heat generation, which will increase the local use of gas. Are there any signs of an increase or decrease in OPEC’s power, particularly as expressed through its market share? Is the influence of the international oil companies in investment and production decisions in OPEC countries increasing?

Are there any signs of an increase or decrease in OPEC’s power, particularly as expressed through its market share? Is the influence of the international oil companies in investment and production decisions in OPEC countries increasing? Reporters should be on the look out for the development of substitutes to petroleum products. Coal could become a formidable competitor and capture market share from other fuels, especially natural gas, if a way is found to decrease greenhouse-gas emissions from coal combustion. Also, closely monitor efforts at conservation and technological change that reduce the demand for energy.

Reporters should be on the look out for the development of substitutes to petroleum products. Coal could become a formidable competitor and capture market share from other fuels, especially natural gas, if a way is found to decrease greenhouse-gas emissions from coal combustion. Also, closely monitor efforts at conservation and technological change that reduce the demand for energy. Increasing concerns about global warming may, over the next few years, lead to further efforts to reduce the energy intensity of economic growth and to internalize the full economic costs of the production and use of different fuels. This could have major effects on the price of gas and oil compared to other energy carriers.

Increasing concerns about global warming may, over the next few years, lead to further efforts to reduce the energy intensity of economic growth and to internalize the full economic costs of the production and use of different fuels. This could have major effects on the price of gas and oil compared to other energy carriers.