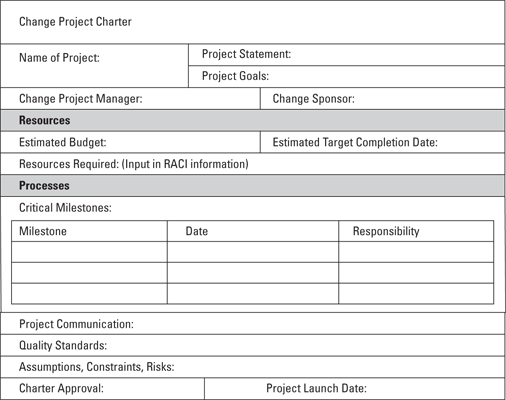

Figure 5-1: A project charter is a living document that summarizes the project plan.

Chapter 5

The Fine Art of Planning for Change (Or Dealing with the Unplanned Kind)

In This Chapter

Figuring out what will happen and getting it into writing

Figuring out what will happen and getting it into writing

Outlining the process for change

Outlining the process for change

Limiting the scope appropriately

Limiting the scope appropriately

Keeping cool in the face of unexpected change

Keeping cool in the face of unexpected change

Does this scenario sound familiar? You’re working on a change initiative, it kicked off perfectly, employees are doing their jobs exactly as expected, and energy for the project is focused and moving. And then all of a sudden (or so it seems), the project begins to slow down. People move on to other jobs, perhaps even to other companies. Another project comes up or a barrier is put in the way, and your project that was once on the path to success is stalled like a rusted-out car. What happened?

If your organization is like most, change initiatives progress quickly until they become 90 percent complete, regardless of their impact, scope, or purpose, and then remain at or around 90 percent complete forever. Very few major change projects are implemented perfectly on time, under budget, and with the exact same staff that started the project in the first place. Why, you ask? It’s because 90 percent of projects are stalled by external pitfalls that block the way and because the projects aren’t following a comprehensive plan. Examples of external pitfalls include a competitor releasing a new product, a global recession that changes demand for your products, or new technology changing the way you go about running your business. Internal pitfalls can include lack of involvement of key staff, poorly defined action steps, or insufficient communication, to name a few.

To help your change project beat these odds, you need a comprehensive project plan in place. A good plan helps you maneuver past internal and external pitfalls that otherwise could block the way to the success of the project, its processes, and your organization as a whole.

This chapter provides tools you will use in project planning as you lead change (and just about any other project you need to get done, too). Here, you discover the ins and out of creating a winning project plan and using the GRPI model (goals, roles, process, and interpersonal relationships) to quickly inform people of how the change initiative is being run. We also equip you with ways to focus on the vital areas of the project, avoid scope creep, and understand how to identify what’s absolutely critical to fully accomplish the change goals. Then we walk you through how to tie all these plans together as you develop a project charter to guide you and your organization through anything that comes your way during the change. Finally, we help you plan when you’re facing unexpected change.

Creating a Winning Project Plan: What’s Going to Happen

Although your overall goal is to lead lasting change in your organization (see Chapter 4 for details), your project plan is a short-term design to help create change. Think of the project plan as a blueprint for building a house, only the house is the change you’re trying to achieve. You need the blueprint to make sure the house gets built, but the end goal is not a marvelous blueprint, it is the extraordinary house. That being said, without a blueprint for change, you will have a vision for the future of your organization with no clear idea of how you’re going to build this great future. A winning project plan specifies how you’re going to get to your desired future state.

Checking your readiness to launch

Most project-management methods have common fundamental areas: scoping, planning, managing, and closing. Before you can begin writing a project plan, you need to spend some time thinking about these areas of the project. If you can answer the following eight readiness questions, you’re well on your way to creating a winning project plan:

Scope

Scope

• What are we trying to do?

Planning

Planning

• When will we start?

• Who will do the work and make decisions?

• How long will the project take?

• How much will the project cost?

Managing

Managing

• What work needs to get done?

• How will we make sure the work gets done?

Closing

Closing

• How will we know we have been successful?

If you were able to answer all eight questions with no trouble or hesitation, you can jump ahead to creating your project charter and moving ahead with your change plan (we discuss the charter later in “Using project charters to stay on track”). If you feel that your answers may need a little more oomph (technical term) or substance, don’t worry. You are in the same place as 99 percent of other change leaders when they begin embarking on change. Now is the time to move straight into project planning basics to get your project moving. The tools in this chapter help you get to the point of being ready to launch your change.

Planning to succeed

How are you going to do all this planning? Well, the first answer is that you won’t do it alone. You shouldn’t be expected to know everything about the project, and that’s why your fellow change leaders, change agents, and project team are there to support you. In Chapter 4 we focus on getting your team, vision, and shared needs aligned and ready to roll; now you can use that marvelous team to make sure the plan is realistic, actionable, and measureable.

Even if people are ready to get changing now, you still have time for planning — if you make time for it. If you don’t do it, you most likely will be playing catch up later. So wouldn’t you rather plan to succeed instead of pulling a few all-nighters dealing with risks you should have known about and tried to mitigate before they happened?

Doing the following things will make your life easier during the planning phase:

Identify the types of project management in your organization that you have used in the past: Don’t start from scratch if you don’t have to. You may be surprised to find that your organization has a project-planning method or template you may be able to modify to meet the needs of your change.

Identify the types of project management in your organization that you have used in the past: Don’t start from scratch if you don’t have to. You may be surprised to find that your organization has a project-planning method or template you may be able to modify to meet the needs of your change.

Piggy-back onto existing project management tools: Some organizations already have program offices in place or perhaps even project managers. If your organization has this resource, use it! If not, the Association of Project Management and the Project Management Institute have wonderful resources available on their websites for new and experienced project managers. You may want to consider joining these organizations to access a wealth of tools and information.

Piggy-back onto existing project management tools: Some organizations already have program offices in place or perhaps even project managers. If your organization has this resource, use it! If not, the Association of Project Management and the Project Management Institute have wonderful resources available on their websites for new and experienced project managers. You may want to consider joining these organizations to access a wealth of tools and information.

Looking at the elements of a project plan

If you have been on a project before (and who hasn’t?), you may think that putting together a project plan is basically creating a project schedule or Gantt chart. Although having a project schedule is absolutely critical, the schedule is just one piece of the project-planning puzzle. This section covers the elements of a project plan to get you on the right path to successful change.

Writing a project problem statement

The problem statement is a one- or two-sentence description of the symptoms arising from the problem to be addressed. It often parallels a business case for change quite closely, but the problem statement is more specific and focused than the business case. For example, “Turnover in our research department has increased from last year’s level for three quarters in a row, reducing our knowledge base and limiting new product development.” A problem statement then focuses on a key element of that larger issue: “Experienced engineers have left the company three times as often as last year, contributing to a significant reduction in new product introduction.” Problem statements usually answer these questions:

What’s wrong?

What’s wrong?

Where is the problem appearing?

Where is the problem appearing?

When did the problem happen (time frame)?

When did the problem happen (time frame)?

How big is the problem?

How big is the problem?

What’s the impact of the problem on the business?

What’s the impact of the problem on the business?

Defining the goal of the project

Making a great project plan is a waste of time if you aren’t certain of where you want to go. Defining your destination, the goal of the project, should be pretty easy because all you have to do is state what you expect to get out of the project. If this step sounds familiar, it’s because it ties straight back to the vision of the change, discussed in Chapter 4.

Be specific about what the project is aiming to accomplish and make sure to define measurements around how you’ll know the goal has been met. To help you come up with the goal of the project, refer back to your vision from Chapter 4 and refine it by asking yourself these questions:

What are you trying to get done? What do you want to happen? What end result(s) do you expect to achieve from this project? These answers are the team’s change objective, and it often starts with an action verb like improve, control, or increase.

What are you trying to get done? What do you want to happen? What end result(s) do you expect to achieve from this project? These answers are the team’s change objective, and it often starts with an action verb like improve, control, or increase.

How will you know that any changes have resulted in improvements? Use SMART factors later to describe your results. To make sure you have SMART goals, make sure the goal is specific, measurable, action oriented and agreed on, realistic, and time bound (see the nearby sidebar for more info).

How will you know that any changes have resulted in improvements? Use SMART factors later to describe your results. To make sure you have SMART goals, make sure the goal is specific, measurable, action oriented and agreed on, realistic, and time bound (see the nearby sidebar for more info).

Who are you trying to reach? List audiences in priority order to make sure you’re focusing your goal in the right direction. You may want to refer to the stakeholder mapping section in Chapter 7 if you need more help determining who your audience should be for the change project.

Who are you trying to reach? List audiences in priority order to make sure you’re focusing your goal in the right direction. You may want to refer to the stakeholder mapping section in Chapter 7 if you need more help determining who your audience should be for the change project.

We’ll illustrate creating a goal statement with an example. Say your change project’s problem statement is focused on how customer information isn’t available to everyone in the organization. Your project goal is to have the entire sales team, customer-service team, and marketing team (measurable and specific) using a new customer-relationship software to cross-sell to and support your customers (action oriented) by the end of the year (time bound). This goal seems realistic because it is related to the various team’s job descriptions, so it’s fully SMART. It also addresses what you’re trying to get done and who you’re trying to reach, so it’s an excellent goal.

Setting quality standards

When it comes to getting a project done, the two ends of the quality spectrum are using the quick-and-dirty method (which often lacks quality) and following previously established standards. Here is where doing a little research on best practices in your industry can really help, so that you can set goals that are competitive. Of course, not every project needs to pass the white glove test, but as a change leader you need to define what standards of quality are required. Will a review council be established to look at the milestones, or will a quality audit make sure deliverables for your change are acceptable?

Allocating financial, human, and physical resources

Nothing gets done without resources. Whether these resources are financial, physical, or human, identifying the necessary resources up front (or lack of them) alleviates a tremendous amount of pain in the future. If you need a project manager, identify the person to fill that role. If you need financial resources to make a technology change, let senior leaders know how much money you need and how you came up with that number. (If you’re facing resistance with gaining resources for the project, you may want to take a glance at Chapter 9 on managing resistance.)

Outlining governance structure

You may have the best plan in place and have all the project resources you could possibly desire, but you still need to know who’s running the show. The governance structure puts down on paper who is making each decision.

By identifying resources, you determine who will do the work, whereas the governance structure shows who oversees the project and makes key decisions on what will get done in what time frame with what level of investment. Please refer to the “Roles and responsibilities” section later in the chapter for more about these assignments.

Noting critical milestones

Critical milestones, also referred to as critical-path items, is just a fancy term for things must happen before going any farther. We discuss these action items in the later section “Identifying critical successes and critical paths.”

Identifying dependencies and risks

Risk management is one of the most bypassed areas of project planning for large changes. Who wants to stand up and talk about the risks of the project not being an overwhelming success when you’re just starting? That’s like telling a bride on her wedding day that her marriage has a 50 percent chance of failing — not a really pleasant conversation.

Change teams also sometimes avoid talking about the project’s dependencies, the factors they’re counting on in order for the project to succeed. For example, a team may require the support of the IT department to make necessary changes to information systems in order to track the progress of the change. This need may require the IT manager to shift priorities and workloads to accommodate this request. We discuss dependencies along with risk because they’re simply risks that you want to have happen.

But dependencies and risks don’t need to be intimidating, because every large change (and small change) holds potential risks and dependencies that can cause problems or delays. Your goal is to highlight them so they can be avoided or reduced through advance planning (sounds much better than failure, right?).

Risks and dependencies usually fall into a range of categories: people, knowledge, funding, materials, equipment, data quality, and market/customer/external concerns. When you identify risks and dependencies, you should ask yourself the following questions:

What risks and dependencies do we know of?

What risks and dependencies do we know of?

What is their potential level of impact on the project timeline and cost?

What is their potential level of impact on the project timeline and cost?

How likely is each risk to cause problems? How likely are we to have something we depend on not happen? Very likely, somewhat, and not at all are just fine as categories. You don’t need to put too fine a point on this.

How likely is each risk to cause problems? How likely are we to have something we depend on not happen? Very likely, somewhat, and not at all are just fine as categories. You don’t need to put too fine a point on this.

Identify ways of reducing the risks or their impact if they do happen. Create a plan for if the risks happen or if the dependencies fail to happen. We go into more detail on assessing and managing risk in Chapter 6.

Scheduling

The most important reason to have a project schedule is to give you and your change team a way of monitoring tasks. Now is the time to list out all those critical milestones (or critical-path items; see “Identifying critical successes and critical paths”) and list what specific tasks are needed to complete each big step. Your spreadsheet or project-management software should be able to provide a template to create a robust project schedule.

Because a project schedule is a critical path in project planning (you can’t go forward without one!), we take a quick look here at what makes a good schedule (hint: it’s not a wonderful software package with pretty charts). A great project schedule identifies the major tasks or deliverables that need to be completed and then groups subtasks together according to how you can make these major tasks happen. The tasks should always imply action. For example, if your major task in the project plan of getting to work in the morning is making coffee, your subtasks may be: grind the beans, fill the water in the coffee maker, push the On button, warm the milk, pour the coffee, and stir in the sugar. Your subtask may instead be getting in the car and getting your local barista to make your cup of joe, but that’s where the art of project planning comes into play. There are many possible ways to make a great cup of coffee. The subtasks nail down the specific approach you plan to use in your project.

The GRPI Model: Getting a Grip on How Change Will Happen

The GRPI model for project and team management is one of the most user-friendly, can-be-done-anywhere models out there. The GRPI model is simply a way of organizing your team around the project plan in a way that makes sense. GRPI stands for

Goals: Clearly define the team’s mission and establish objectives that conform to the SMART approach (that is, goals that are specific, measurable, action oriented and agreed on, realistic, and time bound).

Goals: Clearly define the team’s mission and establish objectives that conform to the SMART approach (that is, goals that are specific, measurable, action oriented and agreed on, realistic, and time bound).

Roles and responsibilities: Clearly define each team member’s function and the interrelationships between individual and team roles, objectives, and processes.

Roles and responsibilities: Clearly define each team member’s function and the interrelationships between individual and team roles, objectives, and processes.

Processes and actions: Identify and define processes inherent in and essential to the project’s success (such as problem solving, decision making, and so on).

Processes and actions: Identify and define processes inherent in and essential to the project’s success (such as problem solving, decision making, and so on).

Interpersonal relationships: Ensure open communication between team members, encourage creative and diverse contributions from all members, and discourage “groupthink” (quickly coming to consensus without critical reflection).

Interpersonal relationships: Ensure open communication between team members, encourage creative and diverse contributions from all members, and discourage “groupthink” (quickly coming to consensus without critical reflection).

By enhancing your project plan with the GRPI model, you get a one-two punch for project success: a solid plan to make sure everyone knows what is going to happen (the project plan) and a structure of how it will happen (the GRPI model). Additionally, using the straightforward GRPI acronym is something most people in organizations can relate to, remember, and grasp with little or no project-management or team training. Use the GRPI acronym as your checklist to make sure you have everything accounted for in your project.

Goals

The first part of your project plan covers the goals of the project and the problem statement. Make sure to include the vision of the project (from Chapter 4), the goals and deliverables of the project (from your project plan), and the scope of the project (which we cover in “Staying Focused on What Matters Most” later in this chapter).

Roles and responsibilities

The R in GRPI stands for roles and responsibilities. This information pulls heavily from the governance structure part of your project plan. A RACI chart is a simple yet effective tool for assessing roles and responsibilities, ensuring the right people are involved (that is, that you have the right management or governance structure). RACI is an acronym for

Responsible: Who is responsible? List the individual or individuals (limit this role to one or two people) in charge of getting the job done.

Responsible: Who is responsible? List the individual or individuals (limit this role to one or two people) in charge of getting the job done.

Accountable: To whom is the responsible person accountable? Make note of the individual or individuals (again, limit this role to one or two people) who have ultimate decision-making and approval authority. It is typically the owner of the budget or resources.

Accountable: To whom is the responsible person accountable? Make note of the individual or individuals (again, limit this role to one or two people) who have ultimate decision-making and approval authority. It is typically the owner of the budget or resources.

Consulted: Who do the responsible and accountable parties need to get input from? The consulted group is the individuals or teams who should provide input into a decision or action before it occurs.

Consulted: Who do the responsible and accountable parties need to get input from? The consulted group is the individuals or teams who should provide input into a decision or action before it occurs.

Informed: Who needs to know about the change/project? This group is the individuals or teams who must be informed that a decision or action has taken place. Be sure to include people who will be most impacted by the change.

Informed: Who needs to know about the change/project? This group is the individuals or teams who must be informed that a decision or action has taken place. Be sure to include people who will be most impacted by the change.

Your overall change project will have one big RACI chart as part of the governance structure, but a great next step is to put the RACI model into your project plan as well. After you have completed your RACI chart at the project-schedule level, take a step back and get some perspective on it. Watch out for the following red flags:

Does one person have lots of responsibilities? You will want to make sure this individual can stay on top of so much.

Does one person have lots of responsibilities? You will want to make sure this individual can stay on top of so much.

Are too many people accountable? If too many people are accountable for one activity, it most likely means you don’t have the right person making the final decision. Having too many people accountable for an outcome can muddy the water of who really will make your project the one that gets completed.

Are too many people accountable? If too many people are accountable for one activity, it most likely means you don’t have the right person making the final decision. Having too many people accountable for an outcome can muddy the water of who really will make your project the one that gets completed.

Processes and actions

The processes-and-actions section of the GRPI model focuses more on how the work will get done rather than on what is getting done, which you covered in your project schedule (see the earlier section “Scheduling” for details). In this section of your GRPI model, cover four big “hows” of how to get the plan done:

Decision making: How will decision making take place? Will decision making be in the hands of the project owner (the accountable person), or will the team make decisions and then propose the final solution to the boss? Stating these rules upfront saves time at the end of the project by making sure decisions don’t need to be revisited.

Decision making: How will decision making take place? Will decision making be in the hands of the project owner (the accountable person), or will the team make decisions and then propose the final solution to the boss? Stating these rules upfront saves time at the end of the project by making sure decisions don’t need to be revisited.

Problem solving: You may also want to discuss how you will work through problem solving. Will problem solving be done individually or as a team? Neither method is better than the other, but you can see how conflict will quickly arise if one person expects to handle all the problem solving on her own and the rest of the team thinks group discussions are needed for anything that happens.

Problem solving: You may also want to discuss how you will work through problem solving. Will problem solving be done individually or as a team? Neither method is better than the other, but you can see how conflict will quickly arise if one person expects to handle all the problem solving on her own and the rest of the team thinks group discussions are needed for anything that happens.

Conflicting opinions: What will you do in the face of conflicting opinions? Conflict happens on teams. Entire books are written on conflict management (we have a chapter on it; see Chapter 9). But like all planning that goes into making change happen, laying out the groundwork to make sure people know how to escalate conflicting opinions will put the team in control of resolving tough situations.

Conflicting opinions: What will you do in the face of conflicting opinions? Conflict happens on teams. Entire books are written on conflict management (we have a chapter on it; see Chapter 9). But like all planning that goes into making change happen, laying out the groundwork to make sure people know how to escalate conflicting opinions will put the team in control of resolving tough situations.

Communication: How will the change team stay connected through communication? You probably know that communication is one of the most, if not the most, important aspects of making the change happen and getting the change team to work together. If you are working on a large project, you want to make sure that a number of change agents, change advocates, and executives are involved in the project details, so use this area to map how the change team will communicate with one another. At this point you want to focus on communication processes within the change team itself. We go into greater detail on how to communicate to the broader organization and how to develop your communication plan in Chapter 7.

Communication: How will the change team stay connected through communication? You probably know that communication is one of the most, if not the most, important aspects of making the change happen and getting the change team to work together. If you are working on a large project, you want to make sure that a number of change agents, change advocates, and executives are involved in the project details, so use this area to map how the change team will communicate with one another. At this point you want to focus on communication processes within the change team itself. We go into greater detail on how to communicate to the broader organization and how to develop your communication plan in Chapter 7.

You may be thinking that so many of these processes just evolve as a team works together, and yes, they do tend to create lives of their own. However, when a change team comes together, you don’t necessarily have months (and you definitely don’t have years) to work these things out. So discuss them upfront in one of your first change-agent or change-team meetings and then revisit them often, because just like a project plan and project schedule, things evolve over time.

Interpersonal relationships

The interpersonal-relationships part of the GRPI model can best be described as how the team is going to work together to get the project plan done. This part of the plan focuses on the team that’s driving the change, and you will want to include how your change agents, change sponsors, and change advocates will work with one another and what is acceptable and expected behavior on the team. (For details on the roles of change leaders, see Chapter 3.)

Think of this section as setting down the ground rules for how the project will get done. You may consider addressing some of these key interpersonal areas:

Are openness and outspokenness valued and rewarded on the team, or should differences be handled in a less direct manner?

Are openness and outspokenness valued and rewarded on the team, or should differences be handled in a less direct manner?

What level of flexibility does the team have in working with one another? Can team members revisit ideas already decided on?

What level of flexibility does the team have in working with one another? Can team members revisit ideas already decided on?

How will the team value emotions and feelings about what is happening versus rewarding data and facts?

How will the team value emotions and feelings about what is happening versus rewarding data and facts?

The answers to the above questions are influenced by the overall culture of your organization. Culture dictates the formal and informal ways that things get done in your organization. We go into organizational culture in more detail in Chapter 16. Your change team can create its own subculture, but we recommend you define this in the context of what is happening in the larger organization. For example, is openness between management and employees encouraged and rewarded in your company? What is the level of trust between different levels of management? How is conflict typically addressed?

The interpersonal part of the GRPI model is the ground rules and operating agreements for the team. Although this aspect may seem like fluff to some people, sharing expectations and guidelines builds relationships and fosters productive behaviors on any change team.

Staying Focused on What Matters Most

Organizations, no matter how productive, can only focus on so many things at once. Furthermore, too many simultaneous changes are impossible to track and manage. When you have too many changes happening at once, the problem is usually that the change isn’t aligned with the strategic plan and goals of the organization.

The solution is to make sure you’re focusing your project plan on what matters most. You can do so by identifying the specific actions you need to take and focusing the change team on actions they need to accomplish.

Identifying critical successes and critical paths

Your goal as a change leader is to help the organization set milestones that help keep the change moving forward. Although not all these milestones (or mini-goals) guarantee success, they certainly are strong indicators of whether or not you will have your vision for the change become a reality.

Now here is where it gets tricky: Some changes are hard to measure when they’re in progress. For example, if you’re trying to change the culture, how do you measure whether the organization is more open to different ways of doing things? We mention earlier in the book that change in business is both an art and a science, so here is where you may need to brush up on your artistic skills. If you are trying to make the company more innovative, your end measure may be the company’s ability to introduce ten new products successfully each year. But that number is an end goal, so you want a marker to indicate whether or not you are on track to getting those new products out the door each year. You could measure each product getting out the door as a marker of success, or you can create a success marker like these: Do teams meet weekly to try new ideas? Do managers allow time for brainstorming creative ways of doing things as part of their monthly meetings? Have you provided training and coaching on ways to be more innovative?

Critical-path items are milestones that are forks in the road — you can’t just keep moving forward without making a decision. They impact downstream milestones and the overall timeline of project. If you miss a critical path, the entire project will most likely be delayed (or you’ll have to dash around to make up ground).

Two aspects of critical paths you may want to consider are

Assigning a resource to them

Assigning a resource to them

Identifying what depends on them in case they don’t happen according to plan

Identifying what depends on them in case they don’t happen according to plan

You don’t have to think of the worst possible thing that could happen, but be realistic about the potential for the project to be delayed or not adopted fully if critical milestones are not met. You may highlight critical milestones in your project plan with big letters in your Gantt chart, but this is a great place to get visual. For information on how to build a Gantt chart, see Project Management For Dummies, by Stanley E. Portny (Wiley).

Stripping out the work that doesn’t add value

Strategic: These tasks may involve keeping the organization focused on the vision of the future state or continually aligning the change strategy with market forecasts and challenges.

Strategic: These tasks may involve keeping the organization focused on the vision of the future state or continually aligning the change strategy with market forecasts and challenges.

Day-to-day operations: These actions usually are tasks on your project plan, and if they’re not done they’ll lead to missing one of your critical-path milestones.

Day-to-day operations: These actions usually are tasks on your project plan, and if they’re not done they’ll lead to missing one of your critical-path milestones.

Firefighting/nonvalue: This no-value-added work drains your energy and time. It’s most likely work that should have been done correctly the first time but wasn’t.

Firefighting/nonvalue: This no-value-added work drains your energy and time. It’s most likely work that should have been done correctly the first time but wasn’t.

Now look at how these three categories balance out. If you’re not focusing on what matters most, you’re probably spending quite a bit of time in the firefighting/nonvalue category and not enough time in the operations and strategic roles. There’s no magic number or formula, but a general rule is that no one on your change team should spend more than 10 percent of their time on no-value-added work.

Look at the list of nonvalue tasks and try to identify trends and similarities. Then work with your change team to stop them from happening. For example, if you’re spending hours creating presentations and then editing them, you may want to bring on a presentation expert. If you seem to be spending all your time on performance issues for the team, it may be time to reset expectations. If something is pulling you and your team away from focusing on what matters most, stop and change it; otherwise you’ll keep doing the same thing, over, and over, and over again.

Avoiding scope creep

Scope creep is a very real concern for even the best change projects and the most robust change plans. You know scope creep when you see it: A project’s goal is meant to solve one problem, and then another problem arises and seems to work its way into the original project, and then another problem comes up and is added to what the original project was meant to solve as well.

How do you limit the project scope effectively and make sure you avoid scope creep?

Be clear on where the project stops and starts. This step gets back to the project goal. If the goal is SMART, you’ll have a much easier time acknowledging when additional work isn’t part of the change.

Be clear on where the project stops and starts. This step gets back to the project goal. If the goal is SMART, you’ll have a much easier time acknowledging when additional work isn’t part of the change.

Communicate what is inside of the project scope and what is outside of the project scope. This advice may seem obvious, but many people assume your change project is going to solve everything in the entire world — and why wouldn’t it, with such a great vision of the future? Do not overpromise what the change will do. Be open about what it will and will not do.

Communicate what is inside of the project scope and what is outside of the project scope. This advice may seem obvious, but many people assume your change project is going to solve everything in the entire world — and why wouldn’t it, with such a great vision of the future? Do not overpromise what the change will do. Be open about what it will and will not do.

For example, you may have a change that focuses on altering the culture of a company from a traditional bureaucracy to an open, flat organization. You can change management structure, you can change the office layouts, and you may even change how people are rewarded, but you may not be able to take on changing all the information systems that tend to slow down decision making. Anything with that large of a scope may need to fall into the next big change project your organization tackles.

Using project charters to stay on track

After all this work, you’re almost ready to get moving. At this point, many good project managers wrap it up and get moving with their project plan and GRPI model. But one final tool helps you pull everything together to keep the project on track. A project charter is a one-page document that is usually available for anyone in the organization to review. Each part of the charter covers pieces of the project plan and GRPI model. For a visual of the project charter, see Figure 5-1.

What makes a charter different than a project plan? You can’t have a project charter without a clear project plan. Although the project plan has enough detail to get and keep you on the right path, the charter is a high-level plan that the change sponsor has signed. Some teams use the terms charter and project plan interchangeably, and that’s just fine if it works for your team.

Leading Unexpected Change

Even though you may have done your best to identify possible risks to your project, you may still be surprised by things that you would never have been able to predict. Being surprised by winning the lottery is one thing, but no one likes surprises in business. When you wake up one morning and your business is turned upside down (or at least shaken up), stressed doesn’t even begin to describe how you’ll feel. Unexpected change isn’t something to be disregarded and brushed under the carpet. When change is knocking at your door and you weren’t expecting it, you need to immediately strategize thoroughly on what to do next.

Planning your response to out-of-the-blue changes

A number of challenges happen when you don’t have time to plan for change. The biggest of them is trying to plan and change direction when you’re also trying to keep the business running. This challenge is real but not insurmountable.

In this section, we cover areas that need to be part of your action plan to address unexpected change.

Clarify goals and objectives

If an organization faces unforeseen change, one of the first areas you want to address is clarifying the goals and objectives of the company and revisiting roles and specific performance standards. If a big external or internal change happens, you want to be crystal clear on what the business will continue to deliver and who is going to deliver it.

Decide how to shift resources

Lack of resources or changing resources is the outcome of many sudden changes. A fall in market demand, an increase in competition, or instability in the market after disasters all have a significant effect on businesses. When sudden change happens, identify how money, time, technology, and people will be allocated to address the change while the business continues running.

Increase communication

If communication is important during a planned change (and it is!), you can only imagine how critical communication is when the change is abrupt. Although communicating bad news to employees may be uncomfortable, communicating as much as you can immediately after the change fosters a responsive atmosphere, with employees willing and able to adjust to change. Address the change and what you plan to do (even if you’re still figuring it out) internally with employees and management, and if appropriate for the type of change and challenge you face, communicate externally with your suppliers and customers.

Show strong leadership

Visible leadership is essential when reacting to change. Leaders can provide clear direction and positive motivation to help employees remain optimistic about the future. During times of unanticipated change, people crave the security that confident, straightforward leaders provide.

Involving key stakeholders and employees to gain support

The best way to get a leg up on a sudden change is to start moving. As you work through unexpected change, you need to get your stakeholders together, and you need to get them together fast. Write up an action plan, be realistic in what can and cannot be done in the short-term and long-term, and engage your stakeholders to help you quickly gain support for the plan.

Having clear and visible senior-management support for the action plan is the first way you can calm the rocky waters left by sudden change. Quickly pull together a map of your stakeholders showing their roles, interests, and authority, and assess who can influence the company to move in the right direction. Ask key stakeholders for their input and support as you conquer sudden change. Bringing these individuals together to discuss common issues helps them to develop a shared understanding of what’s happening in the business concerning business continuity, strategic direction, performance, communication, and change management.

If you’re trying to get your feet under you again, you’ll have little time or need for an organizational-readiness assessment. Ready or not, change is here! However, the stakeholders can help create and prioritize recommendations that are a match for the organization.

Your employees are also an important resource during times of unexpected change. After updating employees on the situation, engage key employees — the ones who can influence other employees and support you by developing actions to address the change — by pulling them into the conversation. Unexpected changes in a business can worry employees, so it’s more important than ever to keep everyone in the loop of what the leadership is planning on doing to address change. Although getting key employees involved may just seem like one more thing to do, it gives you extra eyes, ears, and legs to overcome sudden change.

This chapter covers the basics of project planning for change, but if you need more in-depth discussion on project planning, you can get on the right track by picking up a copy of

This chapter covers the basics of project planning for change, but if you need more in-depth discussion on project planning, you can get on the right track by picking up a copy of  Project planning is part science and part art. Established tools and frameworks provide a method for delivering results. Following step-by-step instructions to map out the time, budget, and resources you’ll need is often the easier side of project planning. The art side of project planning, the part you have to feel out as you go, is sometimes more difficult, especially when it comes to working with the emotional reactions of the people involved in and impacted by the change. We encourage you to start thinking of project planning not just as a piece of paper but as a mindset of how you do business. It is a disciplined approach to leading change and perhaps even managing the chaos during the transition period. Both of these elements should be in place as you create your project plan.

Project planning is part science and part art. Established tools and frameworks provide a method for delivering results. Following step-by-step instructions to map out the time, budget, and resources you’ll need is often the easier side of project planning. The art side of project planning, the part you have to feel out as you go, is sometimes more difficult, especially when it comes to working with the emotional reactions of the people involved in and impacted by the change. We encourage you to start thinking of project planning not just as a piece of paper but as a mindset of how you do business. It is a disciplined approach to leading change and perhaps even managing the chaos during the transition period. Both of these elements should be in place as you create your project plan. We have known some fairly highly paid consultants to spend weeks, if not months, glued in front of their computers, ignoring family, friends, and clients to make the perfect schedule. But making a perfect schedule is impossible — you can’t plan the next two years with certainty. You’re much better off creating functional pieces of deliverables or critical things you must do, planning out the overall timeline of the project, and then working through the project schedule in portions. We aren’t saying you should be vague or careless; rather, be realistic. Things will happen that will cause dates and tasks to change. Trust us and tear yourself away from that computer screen. Your family and friends will thank us.

We have known some fairly highly paid consultants to spend weeks, if not months, glued in front of their computers, ignoring family, friends, and clients to make the perfect schedule. But making a perfect schedule is impossible — you can’t plan the next two years with certainty. You’re much better off creating functional pieces of deliverables or critical things you must do, planning out the overall timeline of the project, and then working through the project schedule in portions. We aren’t saying you should be vague or careless; rather, be realistic. Things will happen that will cause dates and tasks to change. Trust us and tear yourself away from that computer screen. Your family and friends will thank us.