SLEEPING-BAG ACCESSORIES

BAG LINERS

Purchasing a bag liner is a good way to warm up your bag without adding much cost or weight. There are three types of bag liners: overbags, vapor barriers, and plain inner liners.

OVERBAGS: An overbag slides over your sleeping bag and has a fill that increases the warmth of your bag by as much as 20 degrees. They cost approximately $50 to $100 and weigh about two to three pounds—kind of bulky for extensive backpacking but not too bad for short, cold-weather trips.

VAPOR BARRIERS: These liners are inserted inside your sleeping bag and can raise its temperature by as much as 15 degrees. Basically, with the vapor barrier, you’re sticking yourself inside a plastic bag. They are constructed out of coated nylon or other materials and weigh only five to six ounces. Also, they cost much less than the overbags—approximately $20 to $30. The drawback to the vapor barrier is comfort; they make you sweat and use your own warmth to keep you warm. Vapor liners are recommended for temperatures well below freezing.

PLAIN INNER LINERS: You can also purchase simple bag liners made of flannel, cotton, breathable nylon, synthetics, and down, costing anywhere from $5 to $100 and weighing three ounces to two pounds. The degree to which they warm your bag varies and should be clarified by the salesperson before you decide to purchase such a liner.

SLEEPING PADS

Sleeping pads are a necessity. If you don’t sleep on a pad, you lose your heat to the ground. Although the padding is minimal, they are more comfortable than the hard earth. Fortunately, as with all things backpacking-gear related, there are plenty of pads to choose from, and you are sure to find one that meets your needs.

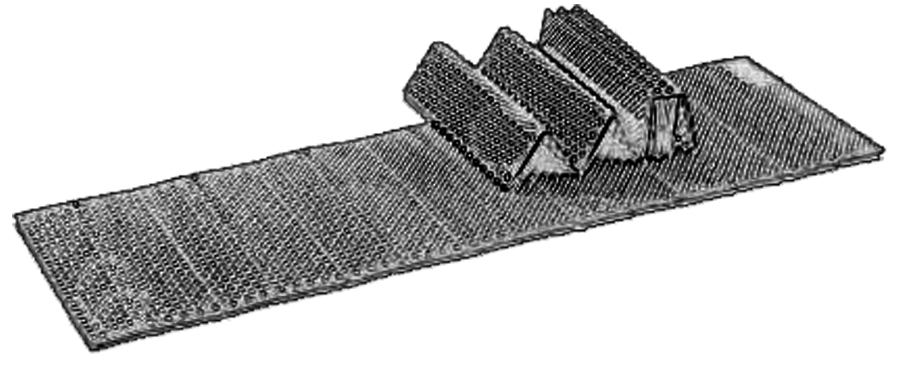

CLOSED-CELL FOAM: This type of pad features tiny plastic bubbles squeezed together in a honeycomb-style. These are both inexpensive and lightweight and they shed water to boot. Closed-cell foam is also pretty durable. Its drawback? It needs to be relatively thick to block out those roots and rocks and, of course, the thicker the pad, the bulkier.

OPEN-CELL FOAM: This is the opposite of the closed-cell pad. Think egg-crate mattress, and you get the general idea. This type of pad always reminds me of the inside of an egg carton and is frequently used in hospitals for bed-ridden patients. This pad offers excellent comfort and contours, is inexpensive, and packs down small. Unless it has a waterproof coating though, it becomes a sponge in the vicinity of water.

Sleeping pad (Therm-a-Rest Z-Lite)

SELF-INFLATING PAD: Who hasn’t heard the one about the hiker who was like a Therm-A-Rest? That’s right! Self-inflating! This is an open-cell foam pad encased in a watertight, airtight cover. It is fitted with a valve to allow you to inflate it. This is achieved by unscrewing the valve, unrolling the pad, and waiting while the foam rebounds, drawing in air, and returns it to its original shape. This pad provides the best comfort available. But, of course, it has its drawbacks, too. It is expensive, on the heavy side, and susceptible to puncture.

OTHER MATERIALS: Other pad options include those filled with heat reflective materials and those filled with down.

After deciding on which type of pad you want to purchase, you might also want to look into the different features available in pads these days. One of the most popular pad features are pads that convert to chairs. These pads have buckles and straps that allow you to turn your sleeping pad into a camp chair. You can also buy a conversion kit that will turn any pad into a chair.

Some pads come with what are known as integral compression or roll straps. These make shrinking and packing your pad a bit easier. The straps also give you more options when it comes to attaching the pad on the outside of your pack.

Pads with multiple chambers allow you to over-inflate one section without creating an annoying bubble elsewhere. Another bonus is that should the pad puncture, only one chamber will deflate rather than the entire pad. The seams between pads affect the insulation on these pads, though. Cold air can creep through at these junctures.

Some closed-cell pads feature a molded surface that is dimpled or ridged. They are preferable to the flat models due to less slippage, better cushioning, and less weight.

A new gimmick to save on weight and bulk is the mummy-shaped pad. The main drawback is that you need to be one of those people who sleeps soundly and doesn’t move around a lot in your sleep otherwise you might find your feet slipping off the tapered bottom section.

Another kind of cool feature of pads is the no-slip surface. A brushed or sticky surface on your sleeping pad helps your sleeping bag maintain the traction it needs to stay on your pad, especially on uneven campsites.

Some pads come with an attached pillow, but these tend to be bulky and most hikers can do with a rolled-up jacket or sweater beneath their head.

Two other features you might want to look for are the repair kit and stuff sack. The former is particularly important because a few patches and fix-it glue might make the difference between a good night’s sleep and waking up on the wrong side of the sleeping bag. A stuff sack is just added insurance against trail grime and possible puncture if you have a self-inflating pad.

When it comes to determining the thickness, weight, and length of your pad, your own preferences are the best judge. You know how much padding you need and how much weight you can carry. Your height, too, will affect how long your pad needs to be.

PILLOWS

Some people cannot sleep without a pillow. Whenever I hike, I use my pile jacket as a pillow. I carry it anyway so there’s not the added bulk of a camping pillow. I consider camp pillows needless weight even on short backpacking trips, but for those of you who wish to carry the extra half-pound, you have the choice of a small (10–12 by 16–20 inches) synthetic stuffed pillow or an inflatable pillow. Relatively inexpensive, backpacking pillows are a matter of preference.

Pack your sleeping bag into a garbage bag before loading it into its stuff sack. This will keep the day’s rain from ruining a good night’s sleep. This is critical with down sleeping bags, which loose their ability to insulate when wet. If you will be fording a stream or are expecting hard rains, put the stuff sack into another bag to doubly protect your sleeping bag.