ANIMALS AND INSECTS

If you hike on the Appalachian Trail, you are bound to meet up with some sort of wildlife. Whether it be a lowly shelter mouse or the majestic moose, backpacking will give you a more intimate look at the animals you share the outdoors with. Sometimes people ask us if we have encountered problems with snakes and bears on the A.T. They want to hear a good story. What we tell them is that the only problem is not seeing them as often as we would like. After all, most every hiker–animal encounter is positive, a highlight of your hike.

Do not let the following words of caution discourage you from getting out on the Trail. The Trail belongs to the wildlife as well as the hikers, and a little caution and courtesy toward animals will go a long way. The following are among the animals that hikers are likely to meet while hiking on the A.T. You should know how to react to them to minimize potential problems.

BLACK BEARS

Black bears inhabit almost every region of the Appalachian Trail. They are usually shy, avoiding contact with humans. Hikers on most areas of the A.T. never see a bear. However, once a bear becomes habituated to people and learns to associate them with food, it may lose its fear of people. This can happen even in areas where bears are hunted. While black bears rarely inflict injuries, they can be aggressive in obtaining food.

Rangers in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park offer this advice: “If you see a bear at a distance, do no approach it. If your presence causes the bear to change its behavior (the bear stops feeding, changes travel direction, watches you, etc.) you are too close.”

You will know if you are definitely too close when a bear reacts with aggressive behavior—swatting the ground, making loud noises, or charging at you. These behaviors show that the bear is demanding more space. Slowly back away, while maintaining a watchful eye on the bear. Do not run, but increase the distance between you and the bear slowly. In most every instance, the bear will do the same.

If the bear approaches or follows persistently, try changing your direction. If this does not work and the bear is still following, you will need to stand your ground. Shouting at the bear and acting aggressively should frighten it away. If you are with other hikers, work together to look as large as possible. Throw small rocks or other non-food objects at the bear. Use a deterrent such as a trekking pole, if you have one, or a stout stick if one is close at hand. Most importantly: do not run and do not turn away from the bear.

Do not leave food for the bear; this encourages further problems. Most injuries from black-bear attacks are minor and result from a bear attempting to get at people food. If the bear’s behavior indicates that it is after your food and you are physically attacked, move yourself away from the food by slowly backing away.

If the bear shows no interest in your food and you are physically attacked, fight back aggressively with any available object. On the other hand, if it is a female black bear with cubs present, she will defend more aggressively and your best defense is to play dead.

Never, under any circumstances, try to feed a bear or leave food to attract them. Once a bear has tasted human food, he will continue to search for it, which means trouble for the bear as well as humans.

When making camp for the night, stash your food and all “smellables” in a bag and make sure it is securely tied off the ground and between two trees. The bag should be approximately 12 feet off the ground, 6 feet from the tree trunk, and 6 feet below the supporting limb.

In the areas that see the most bears—Georgia, the Nantahalas, the Smokies, Shenandoah National Park, and New Jersey—bearproof means of storage are provided for hikers. Food-storage devices include pully and cable systems, poles, and metal boxes.

SNAKES

In the wild, snakes lie in wait along a path for small rodents or other prey. Coiled along the edge of a trail, waiting for food to pass by, the patient reptiles test the air with their flicking tongues for signs of game.

This image of the snake lying in wait just off the trail is a cause of concern among some hikers; but what about the snake’s view of things? The snake is aware of its place in the food chain; it must watch for predators as well as prey. A hiker making a moderate amount of noise will usually be perceived as a predator and the snake will back off or lie still until the “danger” passes.

Garter snakes, ribbon snakes, and black rat snakes are among the non-venomous snakes commonly found in the Appalachian mountains. Rattlesnakes and copperheads are the only species of venomous snake you could possibly encounter on the Appalachian Trail. Both the rattlesnake and copperhead are not aggressive and will avoid striking a human unless cornered.

To avoid confrontations with snakes, remember to make a little extra noise when you are walking through brush, deep grass, or piles of dead leaves that block your view of the footpath. Though the snakes cannot hear the noise, they do sense the vibrations, which warn them of your approach. By kicking at the brush or leaves slightly, you will make enough noise to cause a snake to slither off or lie still.

The sad truth is that the majority of snakebites occur on and around the hand. This is because folks pick up the snake, venomous or otherwise, for a closer look. Ankle and leg bites are very rare.

Both species of venomous snake prefer areas near rocky outcrops, and copperheads can be found among the boulders that border rocky streams as well. Viewpoints, such as Zeager Cliffs in Pennsylvania, are popular sunning spots for snakes. Venomous snakes do not occur as far north as Maine, and copperheads do not commonly appear in Vermont and New Hampshire. Here are some tips for recognizing these two venomous snakes.

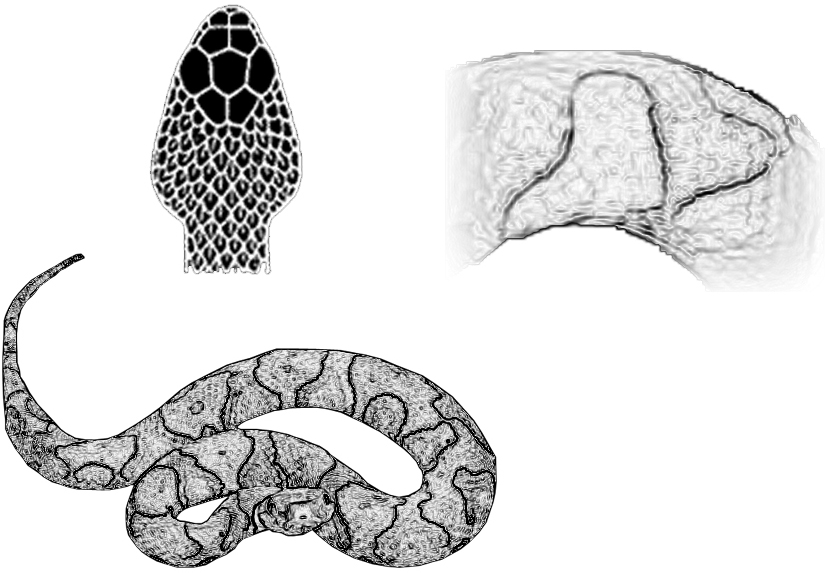

COPPERHEADS

Copperheads are typically two to three feet in length. They have moderately stout-bodies with brown or chestnut hourglass-shaped crossbands. The background color is lighter than the crossbands, anything from reddish brown to chestnut to gray-brown. The margins of the crossbands have a darker outline. This pattern certainly helps the copperhead blend in among dead leaves. Similarly marked but nonvenomous snakes (e.g., corn snake) have similar markings, but none are so distinctively hourglass-shaped.

Copperhead

Copperheads prefer companionship; if you see one copperhead, there are probably other in the area. In the spring and fall they can be seen in groups, particularly in rocky areas.

Copperheads avoid trouble by lying still and will quickly retreat as a last resort. The bite of a copperhead is almost never fatal. Rarely has someone weighing more than 40 pounds died of a copperhead bite. The bite produces discoloration, massive swelling, and severe pain. While not fatal, the bite is dangerous and medical attention should be sought immediately.

RATTLESNAKES

Rattlesnakes are heavy-bodied and can be anywhere from three to five feet long, though large rattlesnakes are increasingly rare. Rattlesnakes also have dark blotches and crossbands (though these are not hourglass-shaped). There are two color phases (i.e., the background color)—a yellowish phase and a dark, almost black one. Sometimes their overall color is dark enough to obscure the pattern. A real giveaway is the prominent rattle or enlarged “button” on the end of the tail. Rattlesnakes usually warn predators with a distinctive rattle; but this can’t be relied on because they may also lie still while hikers go by.

Because of the rattlesnake’s size and resulting larger store of venom, its bite is more serious than that of the copperhead. But like the copperhead, it will strike only as a last resort.

Rattlesnakes are frequently seen on the Trail, though their presence has been greatly reduced by development encroaching on their terrain. Cases of rattlesnake bites are almost unheard of, and when quick action is taken they will almost never prove fatal, except among the very young or very old.

Rattlesnake

TREATING NONVENOMOUS SNAKEBITES

By making a little extra noise in areas where snakes may be hidden from view, you should avoid any chance of a snakebite. If a bite should occur, proper treatment is important.

If not properly cleaned, the wound can become infected. Ideally, the victim should be treated with a tetanus shot to prevent serious infection. Nonvenomous snakebites will cause a moderate amount of swelling. If large amounts of swelling take place, the bite should be treated as if it were caused by a venomous snake.

TREATING VENOMOUS SNAKEBITES

While a venomous snakebite on the A.T. is extremely rare, it is possible, particularly if you venture off the Trail and into the snake’s habitat. Both rattlesnake and copperhead venoms are hemotoxins, which destroy red blood cells and prevent proper blood clotting. Organ degeneration and tissue damage result from the venom. Hemotoxins are quite painful and may result in permanent damage, so swift treatment is essential. Discoloration and swelling of the bite area are the most visible signs. Weakness and rapid pulse are other symptoms. Nausea, vomiting, fading vision, and shock also are possible signs of a venomous bite and may develop in the first hour or so after being bitten.

The best treatment is to reduce the amount of circulation in the area where the bite occurred and seek medical attention immediately. Circulation can be reduced by keeping the victim immobile (which isn’t easy if the bite occurs five miles from the nearest road); by applying a cold, wet cloth to the area; or by using a constricting band. A constricting band is not a tourniquet and should be tight enough only to stop surface flow of blood and decrease the flow of lymph from the wound. The constricting band should not stop blood flow to the limb.

Tourniquets can cause more damage to the victim than a snakebite. If improperly applied, the tourniquet can cause the death of the infected limb and the need for amputation. The cutting and suction methods called for in snakebite kits also are not recommended.

BOAR, MOOSE, AND OTHERS

Boars, which are not indigenous to the United States (they were brought here from Europe for hunting purposes), can be found in the southern Appalachians, especially in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. They are rarely seen and, like most animals, will disappear if they hear you coming. Should you happen upon a boar, try to avoid direct confrontation; just continue hiking.

Male moose should be avoided during rutting season because they may mistake you for a rival and attempt to chase you out of their territory.

Females of any and all species should be avoided when they have their young with them. The instinct for protecting their young is strong and you cannot predict what a mother will do if she feels her children are threatened.

Birds are especially vicious, but generally harmless. You may not see the grouse and her babies but she’ll spot you and let you know that she is not pleased with your presence.

Only the very lucky will catch glimpses of other wild animals—wild cats, wolves, coyotes. Chances of confrontation are slim but, if you do, admire the view and keep walking.

SHELTER PESTS

Appalachian Trail shelters attract rodents and other small mammals. These creatures are searching for food and can do much damage, especially if you do not take care to protect your belongings.

It is never wise, even when camping along the A.T., to leave your pack, and particularly your food, out on the ground or shelter floor for the night. Food, and sometimes whole packs, should be hung where these animals cannot reach them.

PORCUPINES

These nocturnal creatures are shelter pests in the New England states. They love to gnaw on outhouses and shelters and are particularly fond of hiking boots and backpack shoulder straps. That may sound strange, but they are after the salt from your sweat. So hang your packs and boots when you’re hiking in New England, and take particular care in shelters that are known to be frequented by porcupines. Fortunately, most of the shelters have been porcupine proofed: metal strips have been placed along the edges of the shelters to prevent the rodents from chewing on it.

Direct contact is necessary to receive the brunt of the porcupine’s quills. Although it is unlikely for a hiker to be lashed by a porcupine’s tail, it is not unusual for a dog to provoke a porcupine into defending itself. If your dog is attacked and you see quills, you either must pull them with pliers yourself or (preferably) seek help from a veterinarian.

Porcupine quills become embedded in the flesh of the attacker, causing extreme pain. If the quills are not removed immediately, they can cause death, as the quills will continue to work their way through the body in a straight line from the point of entry.

Raccoon

SKUNKS

Skunks inhabit the entire length of the Trail but are really only a problem for hikers in the Smokies. Dogs, on the other hand, can provoke skunk attacks from Georgia to Maine. Although we saw skunks only in the Smokies, we were aware of their presence (that telltale odor!) our entire trip.

During a night at Ice Water Springs Shelter north of Newfound Gap in the Smokies, a brazen skunk wove around our legs as we warmed ourselves in front of the campfire. It was very pleasant, scrounging for scraps of food on the shelter’s dirt floor and along the wire bunks. The skunk occasionally stood on its hind legs and made a begging motion, which had no doubt been perfected on earlier hikers. We didn’t give in to the skunk’s pleas for food, and it eventually crawled back up under the bunks as we sighed in relief.

We heard of another skunk encounter in the same shelter, perhaps with the same skunk, a year earlier, when two British hikers, who were unfamiliar with the animal, tried to chase the skunk away by throwing a boot. They were given a quick course in skunk etiquette!

MICE

Mice are the most common pests in shelters. It doesn’t take long after a new shelter has been built for the mice to arrive. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy states that the shelters are not the place to store, cook, or eat food. Not only will this keep mice out of shelters, but it will reduce other problems. One example is instructive.

In the 1990s, tuna cans suspended on rope started to appear in front of shelters along the Trail. These clever devices were intended to serve as “mouse baffles,” a barrier to mice climbing down onto food bags. Whether the tuna cans discouraged mice or not, the ropes encouraged hikers to hang their smellable bags in the shelters. Bears soon came to see these as meals on a rope.

If you leave your pack sitting on the floor of a shelter, plan on the mice gnawing their way into your pack chasing smells and helping themselves to a mouse-sized portion of your gear. While we were hiking in Virginia, Victoria decided to change into a warmer shirt mid-morning, and was shocked to find that mice had gnawed several holes in the shirt’s collar.

HANTAVIRUS

This virus was first identified during the Korean War and it was named for the Hantaan River there. An abundant crop of pinon nuts in the Southwest in 1993 led to an increased mouse population which in turn led to that area of the country being the first to experience widespread hantavirus. Unfortunately, the deadly strain of the virus that has developed in the United States occurs in backcountry areas, making it a concern for backpackers.

Hantavirus causes a respiratory disease that is carried in wild rodents such as deer mice. People become infected after breathing airborne particles of urine or saliva. Most cases have been associated with 1) occupying rodent-infested areas while hiking or camping; 2) cleaning barns or other outbuildings; 3) disturbing rodent-infested areas while hiking; 4) harvesting fields; or 5) living in or visiting areas that have experienced an increase in rodents.

The virus produces flu-like symptoms and takes one to five weeks to incubate. It has been fatal in 60 percent of victims.

PROBLEM INSECTS

You can’t escape them. They’re everywhere. Even in the coldest reaches of the Arctic and Antarctic, it is not surprising to stumble upon a bug. Mosquitoes, bees, hornets, wasps, fire ants, scorpions, ticks, chiggers, black flies, deer, and horse flies, gnats and no-see-ums are among the millions of insects out there that torment the human soul& and skin.

They invade our lives both indoors and out and, to be perfectly honest, we find insects much easier to deal with in the out-of-doors than inside our home or car. They may be demons outside, but they are Satan incarnate when trapped somewhere they do not want to be. So because you can’t live with them and you can’t live without them, how do you handle insects, especially those that sting, bite, and enjoy feasting on human blood?

BEES, HORNETS, WASPS, YELLOW JACKETS

We’ve only experienced one yellow jacket sting in thousands of miles of hiking. Mostly, these insects will try to avoid you but they are attracted to food, beverages, perfume, scented soaps, and lotions (including deodorant) and bright-colored clothing. Also, they nest anywhere that provides cover—in logs, trees, even underground.

Yellow jackets are the most obnoxious of the bunch, often stinging more than once and without provocation. By keeping your camp clean and food and drink under cover, you should avoid these stinging pests.

If stung by one of these insects, wash the area with soap and water to keep the sting from becoming infected. Apply a cool cloth for about 20 minutes to reduce swelling, and take an oral antihistamine such as Benadryl (diphenhydramine) to reduce swelling as well.

Check your damp clothing and towels before using to make sure a stinging insect has not alighted on it. And remember, bees, hornets, and wasps kill more people in the United States each year than snakes do.

Numerous stings can induce anaphylactic shock, which can be fatal. Those who know they are allergic to bee stings should carry an Anakit (available by prescription) with them into the backcountry. The kit contains a couple of injections of epinephrine and antihistamine tablets. Your doctor should be able to prescribe one for you. If you must use the injection, always get to a hospital as soon as possible for follow-up care.

Anaphylactic shock occurs when the body produces too much histamine in reaction to a bite or sting. The reaction turns your skin red, itchy hives appear, and airways begin to close down, sometimes completely, causing asphyxiation.

If you are presented with a case of anaphylaxis, give the victim antihistamine tablets if they can swallow, or inject epinephrine (follow kit directions) if available. You should be carrying Benadryl or some similar antihistamine in your first-aid kit. Seek help immediately.

For those not allergic to bites and stings, Sting-eze is supposed to be a superior product when it comes to relieving the pain and itching caused by most insects. It is said to combat infection from poison oak, cuts, burns, and abrasions.

BLACKFLIES, DEERFLIES, HORSEFLIES

Most abundant during late spring and summer, these flies produce a painful bite and leave a nasty mark on your skin. They sponge up the blood produced by their bite, which is why the wound is often so big. Deerflies, in particular, seem to prefer to dine on your head. When swarmed by the monsters, I have wrapped my head in two bandanas to avoid their bites. If bitten, wash with soap and water and use an oral antihistamine to reduce swelling and itching.

MOSQUITOES

When camping, there is nothing worse than a mosquito caught in your tent with you. They always seem to vanish, mysteriously, when you turn your flashlight on. Only the females bite (the males like the nectar found in flowers), but there always seem to be plenty of them around.

With cases of West Nile virus becoming increasingly common, mosquitoes are more than a minor nuisance. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, only 1 in 150 people who come in contact with the virus will develop a severe case of the illness. People typically develop symptoms between 3 and 14 days after they are bitten by the infected mosquito.

Progressive symptoms include high fever, headache, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, convulsions, muscle weakness, vision loss, numbness, and paralysis. These symptoms may last several weeks, and neurological effects may be permanent. However, about 80 percent of people infected with West Nile virus will show no symptoms at all. You are more likely to manifest symptoms of the virus if you are over 50 years of age.

Most of the time it is impossible to avoid mosquitoes, but if you camp in open, breezy areas away from still water, there’s a good chance your sleep will be mosquito-free. Go for light-colored clothing that is too thick for mosquitoes to penetrate. If they are really thick, wear long-sleeved shirts and pants and use DEET, which is applied to your clothing rather than your skin.

Wash mosquito bites and use an oral antihistamine to reduce swelling. A paste of baking soda and water also often helps reduce the itching of mosquito bites.

SPIDERS

Anyone who has walked on the A.T. in the early morning has wiped spider webs off his or her face. While most spiders are harmless, there are some poisonous ones. Although it is a fairly unusual occurrence, a few hikers have had unpleasant encounters with brown recluse spiders. The initial bite may not even be felt, but pain will develop within several hours, along with symptoms that may include fever, chills, sweating, nausea, general malaise, and itching around the site. The main sign of this poisonous spider’s bite is a bulls-eye rash, with a dark red or blue center, ringed with red, with another ring of white around it. If you develop these symptoms, seek immediate medical help. Treatment should be received within 48 hours to avoid possible tissue loss. While coma and death can occur, particularly in small children, that is very rare.

Be sure to shake out your clothing and boots before putting them on in the morning.

TICKS

A relative of spiders (another insect that leaves nasty bites), the tick has become a serious health threat. It is the carrier of both Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Lyme disease. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is carried by the wood ticks (west), lone star ticks (southwest), and dog ticks (east and south). Lyme disease is carried by the deer tick, which is about the size of a pinhead.

Whenever you are hiking in tick country—tall grass and underbrush—make sure you check yourself for ticks at the end of each day or more often if you actually notice one on your clothing while hiking. Wearing a hat, long-sleeved shirt, and pants with cuffs tucked into socks will also discourage ticks. This can be very uncomfortable in hot weather. Using a repellent containing permethrin will also help, as will keeping to the center of the trail.

Like mosquitoes, ticks are attracted to heat, often hanging around for months at a time waiting for a hot body to pass. Wearing light-colored clothing will allow you to see ticks. If a tick attaches itself to your body, the best way to remove it is to grasp tick with tweezers and pull, then wash the bite area. Once removed, carefully wash the bite with soap and water.

It takes a while for a tick to become imbedded. If you check yourself thoroughly after each hike—every mole and speck of dirt as well—you are more likely to catch the tick before it catches you. Tick season lasts from April through October, and peak season is from May through July. But in the South, tick season may last year-round if there has been a warmer-than-average winter.

Lyme Disease

More than 23,763 cases of Lyme disease were reported in 2002. The A.T. runs through prime Lyme-disease territory. Ninety-five percent of all cases of Lyme disease come occur in 12 states, 8 of which—Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Hampshire, New York, and Pennsylvania—are also Trail states.

Among the symptoms of Lyme disease are fever, headache, pain, and stiffness in joints and muscles. If left untreated, Lyme disease can produce lifelong impairment of muscular and nervous systems, chronic arthritis, brain injury, and in ten percent of victims, crippling arthritis.

Lyme disease proceeds in three stages (although all three do not necessarily occur):

The first stage may consist of flu-like symptoms (fatigue, headache, muscle and joint pain, swollen glands) and a skin rash with a bright red border. Antibiotic treatment wipes out the infection at this stage.

The second stage may include paralysis of the facial muscles, heart palpitations, light-headedness, shortness of breath, severe headaches, encephalitis, and even meningitis. Other symptoms include irritability, stiff neck, and difficulty concentrating. Pain may move around from joint to joint.

The third stage may take several years to occur and consists of chronic arthritis with numbness, tingling and burning pain, and may include inflammation of the brain itself. The disease can also lead to serious heart complications and attack the liver, eyes, kidney, spleen, and lungs. Memory loss and lack of concentration are also present.

Although antibiotics are used for treatment in each stage, early detection and diagnosis are critical. If you suspect you have Lyme disease, see a doctor immediately.

REPELLENTS

DEET is the hands-down winner when it comes to repelling insects. Short for N-diethyl-meta-toluamide, DEET is found in some percentage in most repellents—lotions, creams, sticks, pump sprays, and aerosols.

This colorless, oily, slightly smelly ingredient is good against mosquitoes, no-see-ums (midges), fleas, ticks, gnats, and flies. Although it can range in percentage from 5 to 95 percent, the most common formulations contain approximately 35 percent DEET.

Repellents containing DEET in the 35-percent range are (in ascending order): Deep Woods Off! lotion, Deep Woods Off! towelettes, Cutter’s Stick, Cutter’s Cream, Cutter’s Cream Evergreen Scent, Cutter’s Cream Single Use Packets (35 percent), Muskol Ultra Maximum Strength, Repel, and Kampers Lotion (47.5 percent, and includes suntan lotion).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that permethrin (which kills ticks on contact) may also be used, but it must be applied to clothes only and not to skin.

Avon’s Skin-So-Soft is a highly recommended deterrent against no-see-ums and some bigger bugs such as sand fleas and black flies. It appears to work differently on each person. Victoria has had better luck with it than Frank has, for example.

DOGS

Some dogs encountered on the trail are hiking companions and others are strays or property of people who live along the Trail’s route. They can be very friendly as well as hard to get rid of when they are strays. They can also be aggressive, especially if they feel they are defending their territory or their masters.

Fortunately, most of the dogs you meet on the A.T. are friendly. While hiking over The Humps (Tennessee) in the aftermath of a snowstorm, we were forced to contend with high winds and limited visibility as well as snow that ranged in depth from two inches to three-foot drifts. A stray dog had appeared at the shelter the previous night, and joined us when we set out for the eight-mile trip to town that morning.

As we climbed blindly over the wind-blown balds, the dog unerringly led us along the Appalachian Trail. At one point, a road very clearly led straight ahead while the Trail turned off to the left. We did not notice the Trail’s turning, but the dog did. He turned left and we followed. Soon we saw blazes at the edge of the woods. Several times during that eight-hour hike, the dog kept us from wandering off the Trail and into the woods when the Trail’s white-blazed trees were hidden beneath snow that had stuck to the trunks.

We also had bad experiences with dogs. In Vermont, a huge Newfoundland stood on its hind legs, barely two inches from Victoria’s face, and growled, menacingly, his teeth bared. The tactic was apparently a very frightening bluff, which left us (and many other hikers) shaking. Stories of this particular dog filled the register at the next shelter.

HOW TO AVOID TROUBLESOME DOGS

As with bears and most other animals, don’t run. Don’t look directly into a dog’s eyes, but if it is necessary to defend yourself, use your hiking stick or small stones. Sometimes just picking up a stone and holding it as if you’re going to throw it is enough to dissuade a dog. Throw the rock only if it’s absolutely necessary.

DOGS AS HIKING PARTNERS

Although dogs can make wonderful hiking partners, most hikers say they really prefer not to hike around people who are hiking with dogs. Unless you have complete control over your animal, you are probably going to make a lot of people unhappy, especially if you intend to stay in a shelter. Two of the biggest complaints from hikers were about wet dogs climbing all over their sleeping bags and other gear, and dogs who tried to eat their food.

If you plan to take a dog, remember that dogs usually are not welcomed by other hikers and do not have priority when it comes to shelter space. Dogs also are not allowed in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (Tennessee and North Carolina), Trailside Museum and Wildlife Center in Bear Mountain State Park in New York, or in Baxter State Park in Maine. At Bear Mountain, there is an alternate road walk for hikers with dogs. On lands under the administration of the National Park Service (NPS), dogs are required to be on a leash. Approximately 40 percent of the Trail—lands acquired specifically to protect the A.T. (about 600 miles) and five of the six other units of the national park system that the Trail crosses: The Blue Ridge Parkway, Shenandoah National Park, the Harpers Ferry and C&O Canal national historic parks, and the Delaware Gap National Recreation Area—are covered by this rule. Dogs are also required to be on a leash through most of Maryland.

Dogs also tend to scare up troublesome run-ins with porcupines and snakes, for example. People hiking with dogs should be aware of the impact of their animals on the Trail environment and their effect on the Trail experience of others:

- Do not allow your pet to chase wildlife.

- Leash your dog around water sources and in sensitive alpine areas.

- Do not allow your dog to stand in springs or other sources of drinking water.

- Be mindful of the rights of other hikers not to be bothered by even a friendly dog.

- Bury your pet’s waste as you would your own.

- Take special measures at shelters. Leash your dog in the shelter area, and ask permission of other hikers before allowing your dog in a shelter. Be prepared to “tent out” when a shelter is crowded, and on rainy days.

Also, if you choose to hike with a dog, you probably won’t see much wildlife. If you wish to backpack or hike with your dog along the Appalachian Trail, you will probably want to read “Hiking with Fido,” an article by veterinarian Tom Grenell. The article is available through the ATC or can be downloaded from their Web site, www.appalachiantrail.org.