There are two ways to get bitten by the entrepreneur bug.

The first is genetic. People with this gene, you know who you are. You can’t help wanting to tinker, going your own way, or regularly showing authority

figures impolite hand gestures—and you answer to no one. This is like being born double-jointed—it can’t be helped. And sure, with time, maybe the inclination to run away from a

preordained life track will fade, but even if you try to cover it up, the urge

to be an entrepreneur will continue to re-emerge. Some people are just born

this way.

The second way is circumstance. Chance, luck, serendipity, whatever you want to

call it. For a lot of people in my generation specifically (millennials is the accepted term), the circumstances surrounding our entrée into the “real world” were dismal. Many of us were forced to give up big dreams of desk jobs and

security and figure something else out.

I had a degree in print journalism, a minor in philosophy, and an internship

that had almost no hope of turning into a secure stream of income. I didn’t want to do what most journalism students were doing, which was either writing

briefs and answering phones at dying print organizations or going to work at a

PR agency for “the man.” So I joined a fledgling journo/marketing project, with the mission to turn a

less-than-mediocre blog into a crowdsourced online magazine.

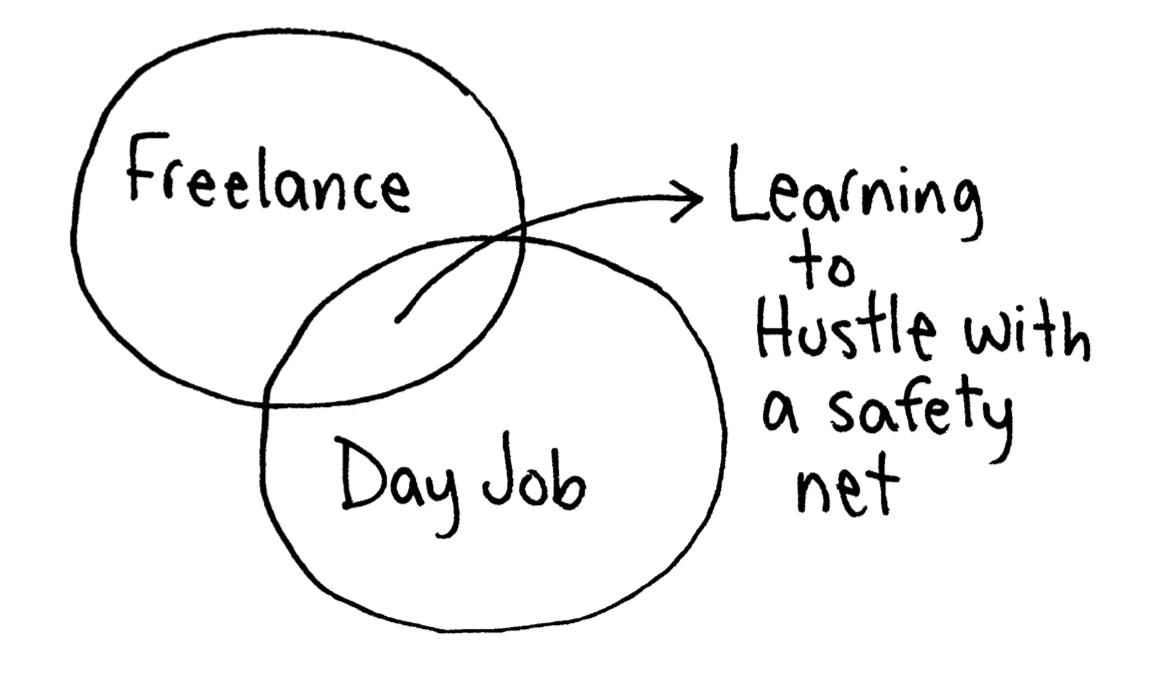

After two and a half years and a lot of freelancing on the side, I parlayed

being the cofounder and editor of the online magazine into a real job at one of

those aforementioned print newspapers. I started another website for “the youths,” as well as managed a number of other projects. But I was pleasantly surprised

to find that the working style I had adopted while freelancing and managing a

shoestring startup in the real world worked just as well when I put it to use

managing a shoestring startup within a newspaper. I’m told that this lifestyle is called “hustling.”

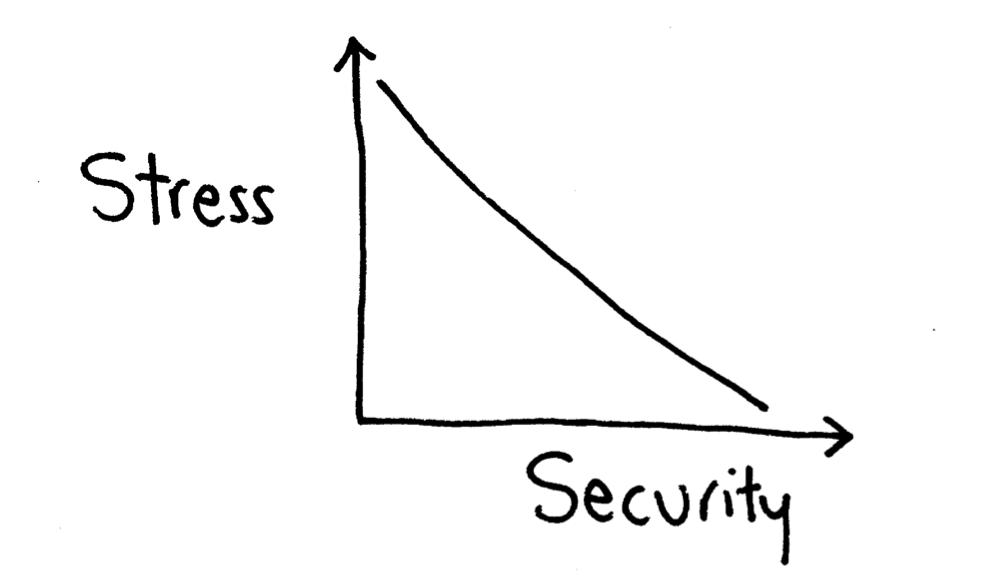

But the hustle can also have a serious downside: extreme mood swings and

worrying levels of depression. According to a recent series of polls by Gallup,

entrepreneurs and freelancers are more stressed and worried than any other

American workers. They are also more likely to feel optimism and are more

interested in their work. A range of industry publications, from the Guardian’s tech section to Inc. magazine, have begun to talk about how this lifestyle can have dramatic impact

on overall mental health, and it’s great that it is finally becoming less of a taboo to talk about.

Without wanting to diminish the very real struggle faced by diagnosed bipolar

individuals, I can’t think of anything else to compare the stress of day-to-day life as an

entrepreneur or freelancer.

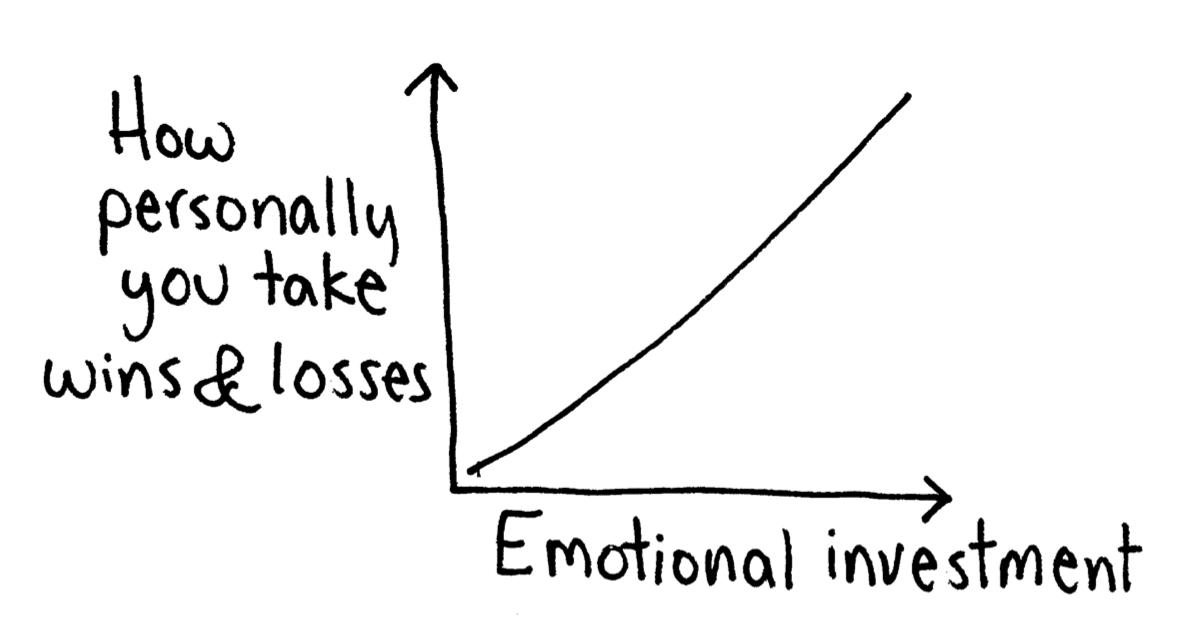

The slightest good news can shoot me into a soaring seizure of maniacal

self-congratulatory glee that can last for days. When I do something well and

my ideas move forward, I feel like I’m on a roll and I can do no wrong. I think positive thoughts: I will be successful! I will be happy! I will be able to show my face at my high

school reunion!

These are the days my body produces the steam that powers my brain wheels, that

makes it physically possible to push myself through large veggie pizzas,

multiple bottles of red wine, and the sleepless, active nights when I do my

best work. This energy is what propelled me to every single startup networking

event and party Boston had to offer for four years, and the race to cover every

base and shake every hand.

But the slightest bad luck or dropped ball, and I am driven into a state of

suicidal melancholy punctuated by bouts of Netflix bingeing, ignoring emails

from work and my mother, and a bad habit of convincing myself that either

everyone I know secretly hates me, or they believe it’s only a matter of time until I fuck up.

When the stock invested in my projects is the blood, sweat, and tears of a very

small team, the burden is enormous. I don’t have the safety of a corporation at my back, or the luxury to work an

eight-hour day. (Who are those people?) The startup lifestyle can be mentally

debilitating, especially because I know something my friends, investors, and

employees don’t: Those success projections aren’t based on science; rather, they’re based on my abilities—and most days I don’t believe I possess the qualities necessary to get the job done. And I’ll have no one to blame but myself when I fail.

I have heard for years from mentors and mentees alike that I am “fearless,” that I “push boundaries,” that I’m a “radical,” that I am “admired.” Let’s just be clear about the fact that to me, this is all bullshit. Professors have

asked me to mentor younger students, managers have forced interns under my

wing, and a lot of times I don’t know why. Mostly this just causes me more stress. Not believing in yourself

and your abilities, I’m told, is another sign of depression.

This rapid fluctuation between the highs and the lows is a trait often found in

intensely creative and ambitious people. We put all of our eggs into baskets

made of our own ideas and plug the holes with dumb luck.

We are pot-smoking paranoiacs with a whole host of à la carte social and performance anxieties, and we don’t know how to deal. We are students of the school of Fake It Till You Make It,

and I am the valedictorian. Knowing this, however, doesn’t make it any easier.

So, how do I deal? Sometimes I don’t, and I give up for days.

But mostly, when I get stressed and messed and start to unravel, I try to take a

deep breath and think about something that isn’t work-related that’s going well, or something that is positive.

I’ll admit that, for a long time, the only thing I could think of was that my cat

really loved me. About 75 percent of the reason I never killed myself when I

lived alone and ran that magazine was because I didn’t trust my beloved cat, Prudence, not to eat my face off before someone found

me. Because let’s be honest, a cat is a cat, and as much as she nuzzles my nose, nature would

compel her to chow down on my lifeless body. Which would make us both sad, and

totally grossed out. So I didn’t commit suicide.

But then, after years of internal struggle, something bizarre happened.

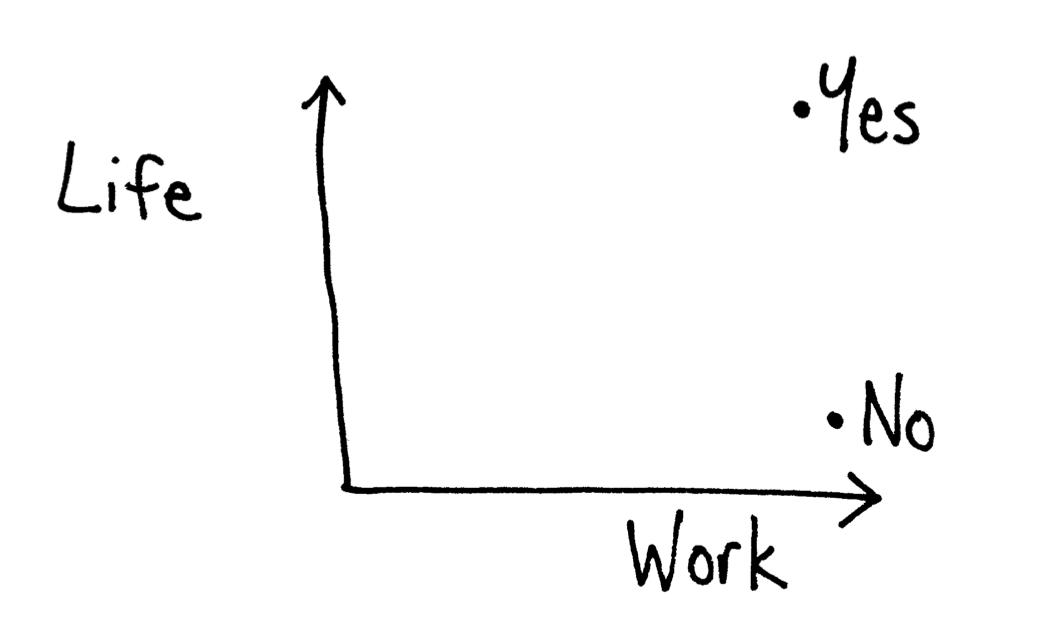

More good things that weren’t work-related started to hog center stage in my life. It took a very long time

and a lot of introspection, but I finally feel like taking a year off from the

treadmill of career climbing to do some art, and it won’t be the worst thing ever. FOMO (fear of missing out) is no longer a thing that

controls my life, and I’m pretty sure digital journalism will still be there when I’m done fucking around with some interesting new ideas.

Life is calling. That cat needs to be nuzzled, the dogs need to be walked, and

my partner needs my love and attention. So if the project has to wait a day, I

finally understand that that’s OK.

But it’s always rosy from the other side of the tunnel, right? And just as I’m starting to figure out how to live with the day-to-day melee of my chosen

lifestyle, there’s always someone else who is still stuck in the muck.

My mother recently quit her job and started her own company doing consulting for

commercial building owners who are looking to make eco-friendly renovations.

Now she’s hustling, too, and she’s exhausted. (Remember what I said about genetics and the bug? I don’t make this shit up.)

Some days she calls me and in one breath is all like, “Wooooo! I got three more contracts! And I went to this networking event, and it

was packed with all these really smart people! And then the organizer said he

knew who I was! HE KNEW WHO I WAS! And he introduced me to, like, twenty other

really big people! And then I finished this really great presentation and took

it to the board of this other building and they loved it, and I wasn’t even nervous and I answered all their questions and it was great! WOOOO!”

But then the other day she called, and it was a rainy day in London. I was

walking to the bus stop, and there was something in her voice that made me wait

two buses to get off the phone with her.

“[Sigh.] Hi. . . How’s it going?” She sounded like Eeyore.

“It’s OK! I’m walking to the bus and I’m going shopping. What’s up with you, Mom?”

“[Sigh.] Well, I just have too much to do. And then that guy I hired who is so

good said at the staff meeting that he’s quitting. And the intern kid just does not know how to do a spreadsheet, and

this whole project got messed up, and now it’s going to be late. And I got another contract, but I thought the guy I hired

was going to be with me to help, and now it’s just so much for one person, and I just feel very sad, like I won’t finish everything in time, or I won’t do it well, and I feel terrible.”

I knew that all I could do was be there and listen, and make sure she knew that

I didn’t think she was going to fail. And even if she did, living means more than

success with a startup project. She sounded like a broken record when she was

saying this stuff to me all those years, but it ended up being true, and I

repeated it back to her.

It was clear to me that my mother caught the entrepreneur bug too, and I

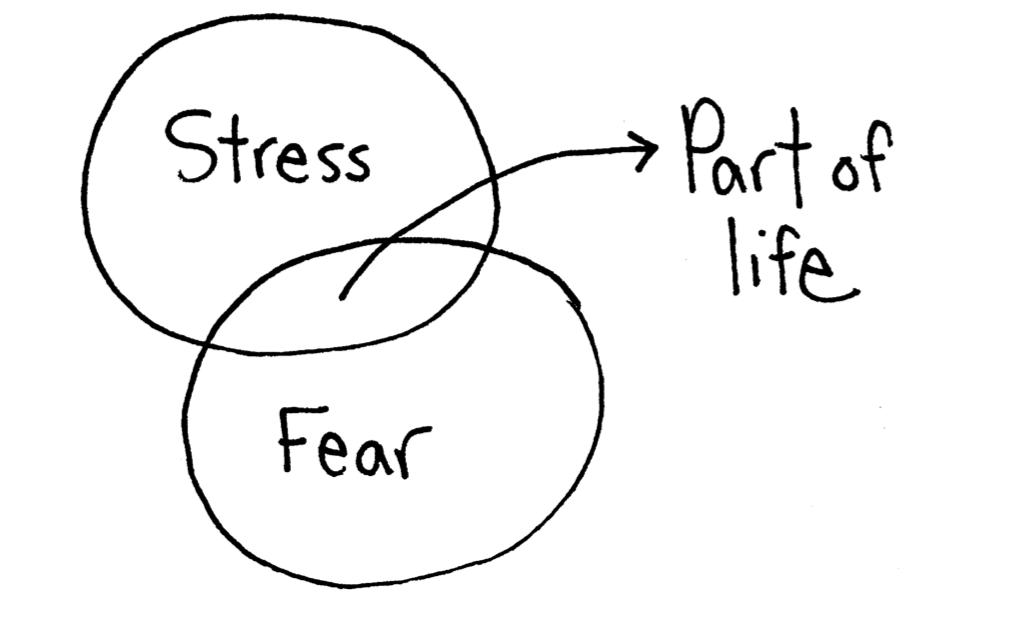

realized that her emotional seesaw wasn’t just our problem—it’s a universal one. It’s a side effect of the virus you catch from spending too much energy on your

money-making idea. And like any impossible virus, there is no cure for this

bug, only acceptance of it.

Mental health professionals say it’s responsible to care for clinical depression by preparing for its onset, like

shutting the storm windows on a house. The life of the hustler isn’t different. But by knowing what to expect, it’s possible to forecast the looming negative effects of the entrepreneur bug on

your mind and body.

They’re not going anywhere, and there is no way to fix them, but there is wisdom in

acceptance of our flaws. Once I understood that the mood swings and the

depression and the frenzied glee are a certain and indisputable part of my

future, it became that much easier to deal with it, set it aside, and keep

plugging on with the next great idea.

List your fears about your work—the terrible things

that make you wince and cringe.

that make you wince and cringe.

***

You may have never said them out loud, or

even thought about them for longer than a stinging moment, so this might be difficult.

even thought about them for longer than a stinging moment, so this might be difficult.

***

Once you’ve articulated those fears, write down the

opposite of your fears—those are your goals.

opposite of your fears—those are your goals.

***

Acknowledging both ends of the success

spectrum will help you cope with ups, downs, and

sideways situations.

spectrum will help you cope with ups, downs, and

sideways situations.