Here’s every Q&A about starting a career in the arts:

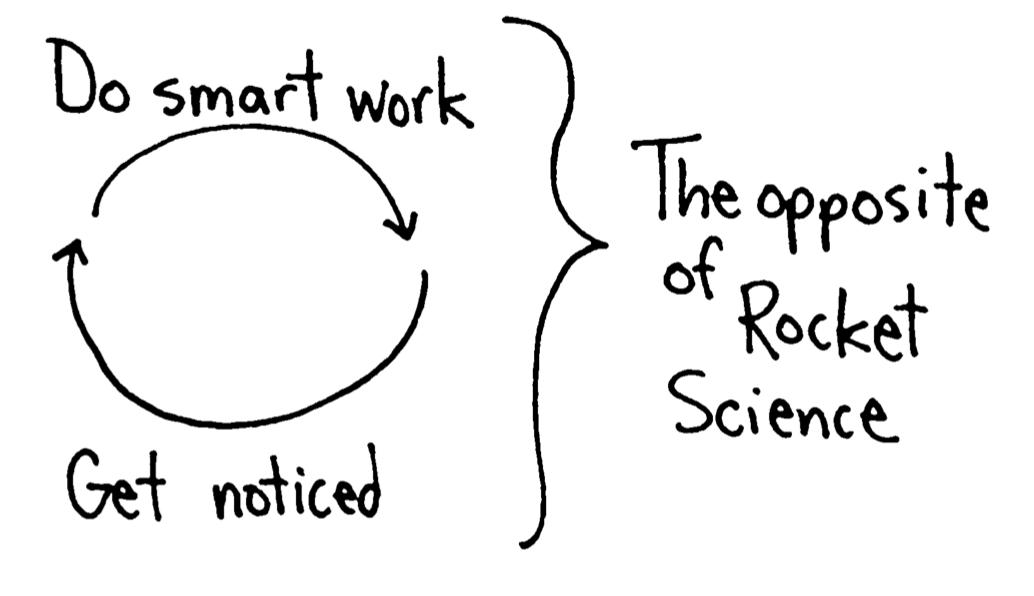

Aspiring creator: “How do I break in?”

Successful creator: “Just make good work and put it out there.”

It’s a smug cliché. It’s frustrating and fatuous, and it’s completely true.

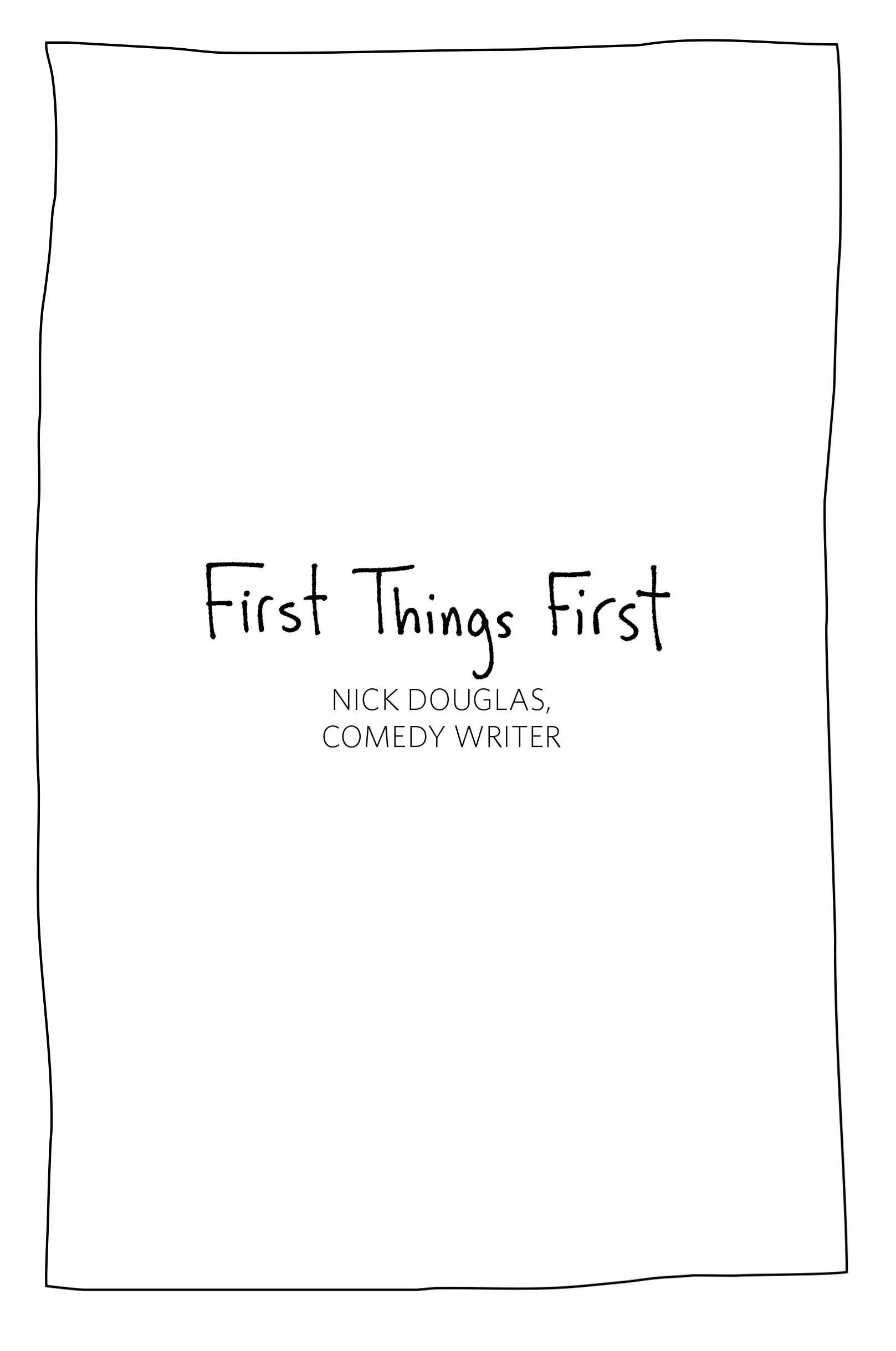

What this seems to leave out is the making connections part and the “playing politics” part. But good news: You make the best connections by just making good work and putting it out there.

It is, in fact, who you know.

Connections are obviously important in creative fields. The best creative gigs

aren’t filled by job board applicants. Someone recommends one friend to another, or

they’ve seen someone’s work. The process isn’t purely meritocratic, but it’s actually very rarely nepotistic (no one wants to risk their reputation by

recommending the wrong friend).

Building connections works the same way as building an audience: Over time, a

creator convinces people that their work is consistently good, enough so that

their next piece of work will be worth betting on. And even more than an

audience, the right connections will feed into your talent.

Make good connections.

I think people imagine “making connections” as social climbing: You find the most famous people you can and try to make

them pay attention to you so they can hand you their next opportunity. You’re right to not want to do that. Don’t.

Instead, make a different kind of connection: Find people you like, regardless

of their status. This will make you feel less awkward, and it’s much easier.

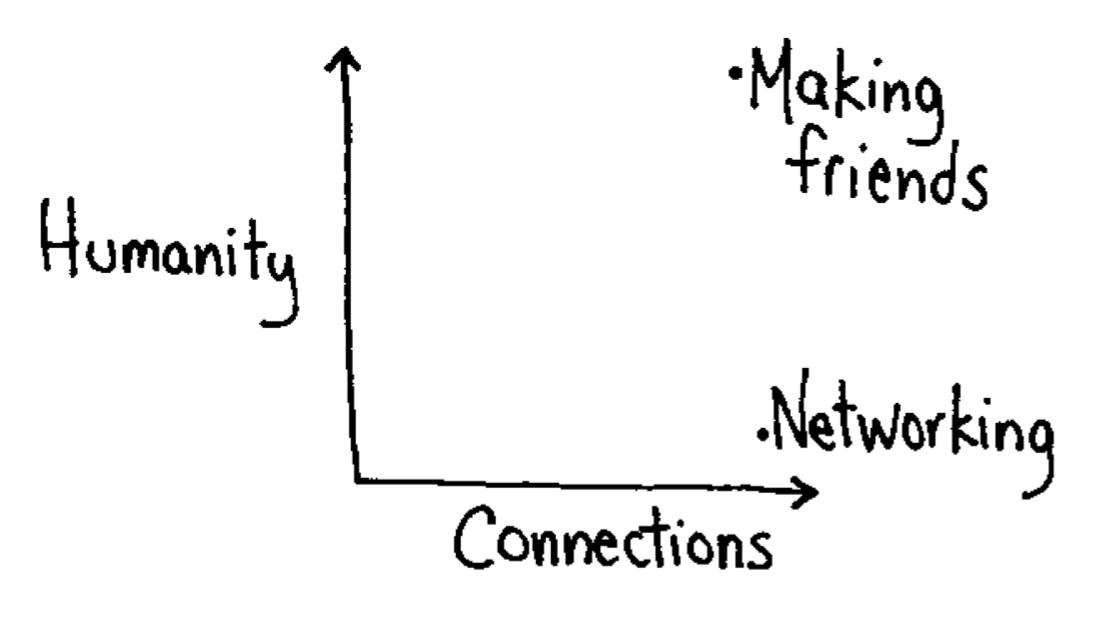

It’s really rewarding when you can help people who are a little behind you in their

career. Not selfishly, not to “earn points,” but because you genuinely feel they deserve more opportunities than they have

right now. So you hire them, or you refer them to a gig, or you make a project

with them, or you promote their work. And you feel like you’re doing everyone else a favor by showing them this underappreciated talent.

Almost all of the time, the people you help will get more opportunities. If they really have talent, you won’t be the only one to notice and reward it. You’ll see your colleagues succeed around and with you. Some will succeed faster.

And if they actually like you, they’ll want to help you out, too. Your assistant might hire you in five years.

How to collaborate.

Don’t be afraid to ask people to collaborate with you. Most creative people love to be asked to join a project, and if they can’t or don’t want to, they’ll probably be polite about declining.

If someone’s an asshole, be overly polite back. Because occasionally you’ll realize years later that you were the asshole: You were unclear, or the project was clearly not a fit for

them, or you made the most common favor-asking mistake—you turned your request into a sales pitch.

I’ve seen hundreds of requests-as-pitches. They’re transparent, and they make me feel like the requestor is hiding something.

While you should clearly lay out the benefits to your would-be collaborator,

don’t be afraid to say how much their contribution would help you. And thank them during and after the project’s completion. People want to help other people! They want to feel important to

your project. And when they do, they’re more likely to promote it.

Pick your collaborators by their talent, creative ambition, and ability to work

with others. Their career status isn’t important; that’s the most fluid variable in any creative person’s life. The absolute most valuable thing is to find people you want to work with

over and over again. Whether or not you officially call yourselves a team, any

time one of you gains a skill or connection, you will both benefit.

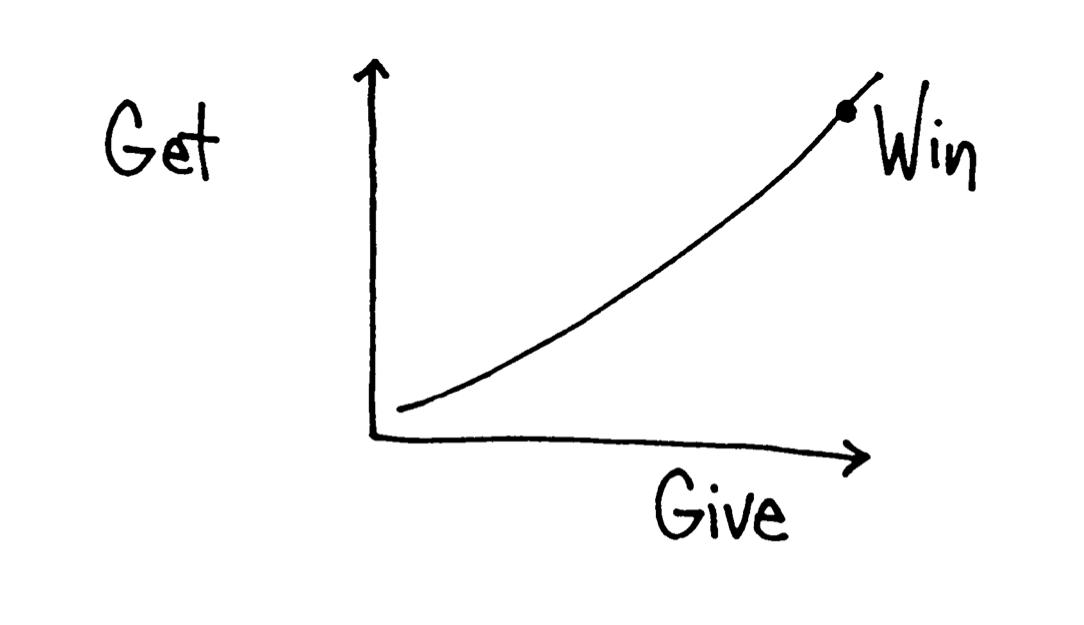

If you’re the one who started a project, even if you’ve brought on an “equal partner,” you’ll probably be the one who pushes to finish it. But if you make a consistent

schedule with your collaborator, you’ll both find it harder to slack off. That’s especially helpful for projects with no real deadline—just keep making new deadlines and be driven by the terror of disappointing your

partner. This is normal. Fake deadlines are secretly why anyone finishes

anything.

Market your stuff, stupid.

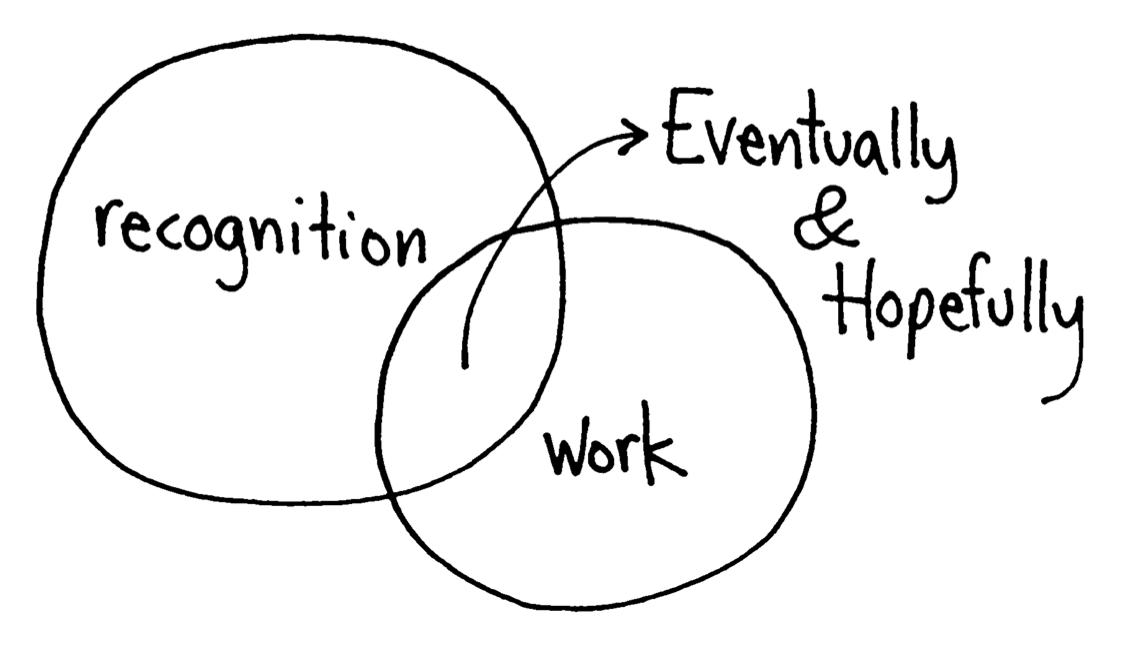

“Putting it out there” primarily means marketing your work. And it’s more important than simply giving an update on your latest piece. Most of the

best creative gigs come from a client or an audience who already knows who you

are. So when you publicize your existing work, you’re also publicizing your future work.

You’re building an identity (which people can follow, because you, of course, have

active profiles on your audience’s preferred social networks). You’re taking the “what you know” that you put into your work, and turning it into “who you know.”

“Putting it out there” also means marketing unfinished work, which is often the real legwork that

subsidizes the fun bits: auditioning, pitching, applying, submitting,

fund-raising. It’s asking people to pay, through purchase, pledge, commission, or paycheck, for

what you’ll make next.

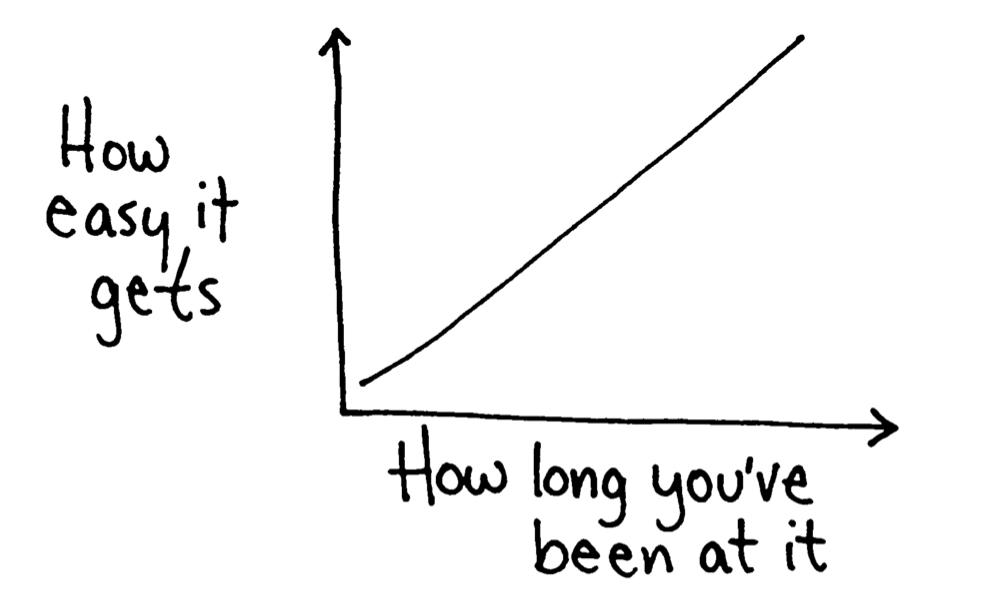

As Kickstarter has demonstrated, asking people for money can be a great way to

introduce them to your work. But pre-marketing works best when the recipient

has already heard of you—which is why it gets easier the longer you’ve been around.

Extroverts get an “unfair” advantage because they make themselves approachable. They actually talk to

their fans; they might even get the fans to interact with each other

independently (the real difference between an audience and a community). They

can present themselves as normal people. That makes it easier for others to

imagine reaching out to them. And you really need to strike people as someone

worth reaching out to.

“Just”

“Just make good work and put it out there.” That first word doesn’t mean “simply,” it means “only.” Don’t procrastinate, don’t hide your work. And don’t make bad work, at least not knowingly.

In his YouTube video “Protect Your Love of Your Work,” poet Steve Roggenbuck warns that if you compromise your work to expand your

audience, “to one degree or another you will successfully reach other people. But once

those people are surrounding you, they’re going to want more and more of what drew them, which was a compromised

version of you.” And you will have less passion to make it for them.

That doesn’t mean don’t listen to criticism or never accept limitations or never do a gig for money.

It just means don’t give up something you value in your own work just to attract people who

currently aren’t interested in you. That’s what it means to be a hack. And as with audiences, so with collaborators and

connections.

Don’t make the connections you think you have to make; they’ll lead you toward work you didn’t want to do, and that’s already the easiest work to get. Make connections by doing your favorite thing

with others’ help, and eventually you’ll get asked to do it again with a bigger budget, or paycheck, or audience.

Working for free.

Creative work is undervalued. Clients underpay, customers pirate, tax systems

are poorly structured—capitalism all around is mostly shitty to all but the most successful creative

artists. And you shouldn’t work for free as often as people want you to.

But you will have to do some work for free. The thing about skilled work is that you have to develop the

skill before it’s worth money. (And just because you’ve gotten paid before doesn’t mean you’ll always get paid again.) But this is the work you do to get known.

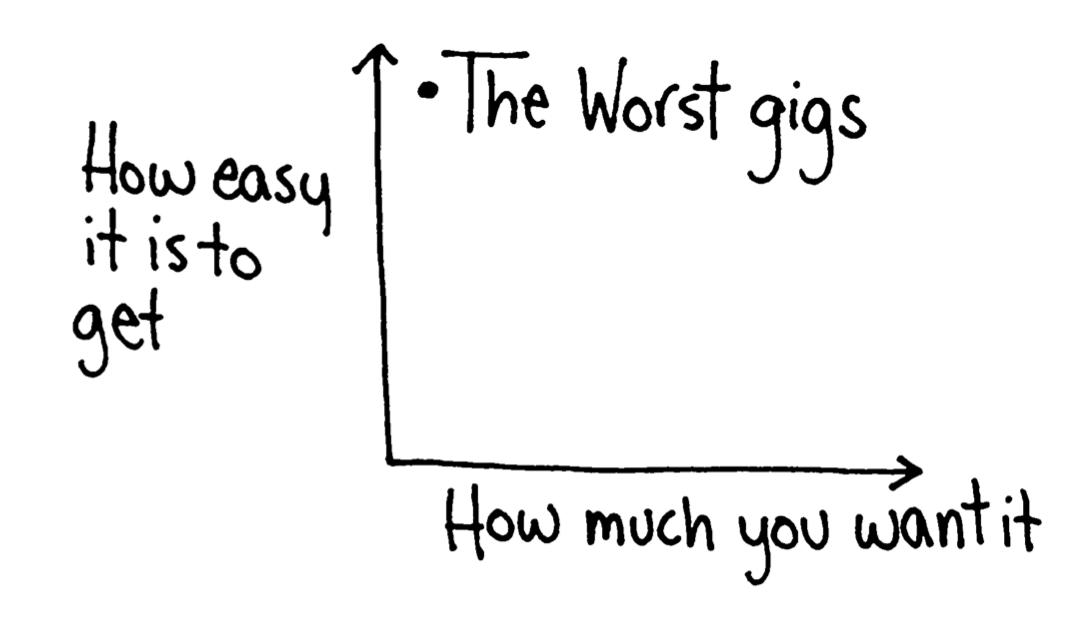

You show some forward momentum: You show that the next thing will be better. You

take every gig you can, because the worst gig can still introduce you to the

person who will hire you for the best gig.

“Overnight success” means nothing but “I missed their early work.” And your early work is where you meet the people you’ll work with for the rest of your life.

Spend at least fifteen minutes making

something new today. Make your work public on

the same day you create it.

something new today. Make your work public on

the same day you create it.

***

Tomorrow, spend at least

twenty minutes making something better

than what you made today.

twenty minutes making something better

than what you made today.

***

Repeat until you are magnificently talented.