There are two types of hustling. The first type is when you know what you want

to do with your life and pursue that dream however possible, inside or outside

the system. Whether your dreams reside in the boardroom or by the easel, you

know what you want and you chase it.

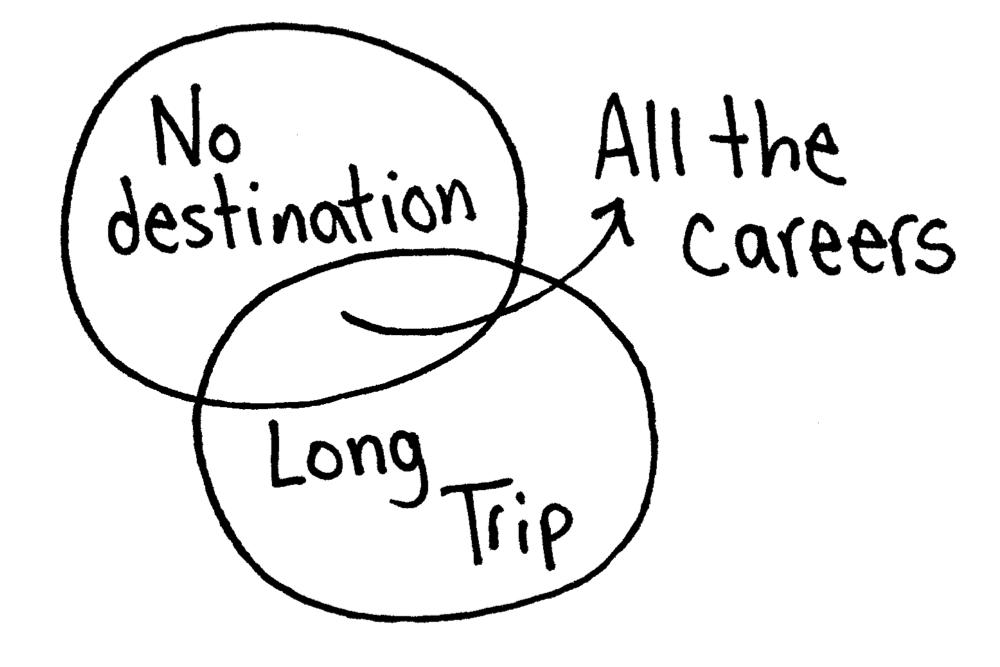

The second type of hustling involves not knowing the specifics of what you want

to do, rather having a sense that you’d like to be interested in your work and be in charge of yourself. Any one path

does not hold the answer, and no specific dream compels your longing.

I am the second type of hustler. I don’t have a career in the traditional sense. What I do have is a résumé full of varied projects and an ever-changing set of skills that has been

cobbled together as those skills have been required of me over the years. And I’ve found that, in this economy, varied projects, interests, and skills

constitute a career.

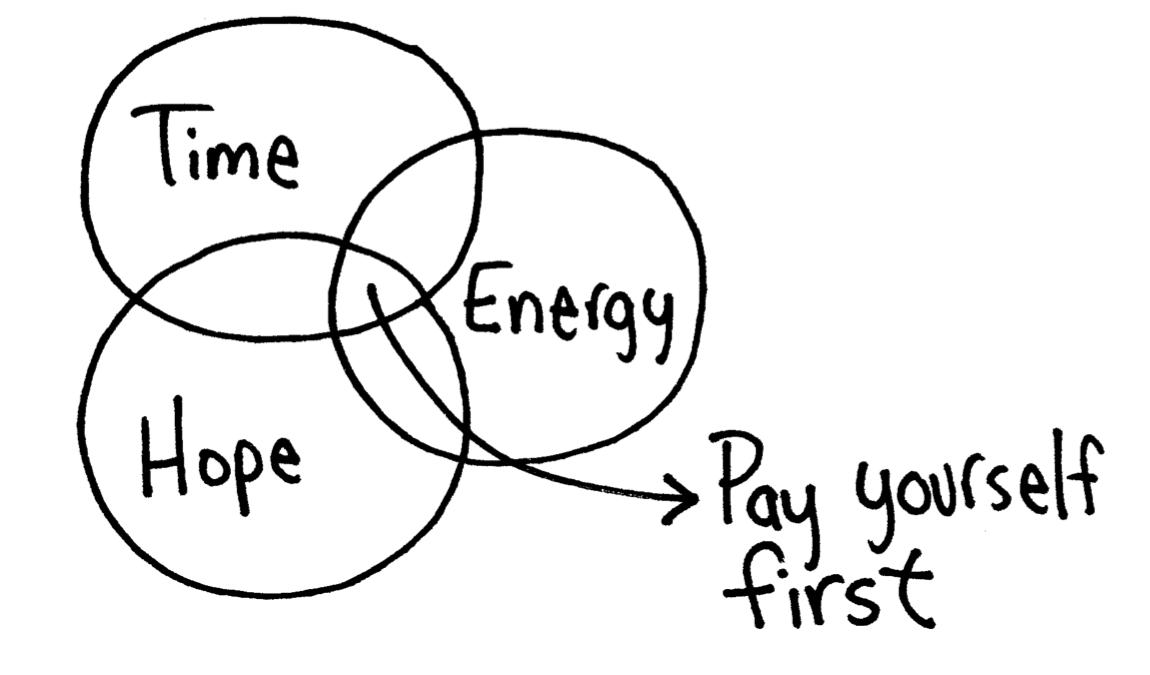

Thanks to the wealth of available knowledge and training the Internet provides,

the decreasing cost of equipment (a lot of which is now software, where it once

was bulky, expensive hardware), and the ease of working remotely, the barrier

to entry for most kinds of work (at least the fun work where you don’t need advanced degrees . . . yawn) has never been lower. This of course assumes

you have time and energy remaining to work on whatever you want to work on,

after you have spent time and energy supporting yourself financially—which is obviously the trickiest part of the equation, so forgive me a lengthy

digression. . . .

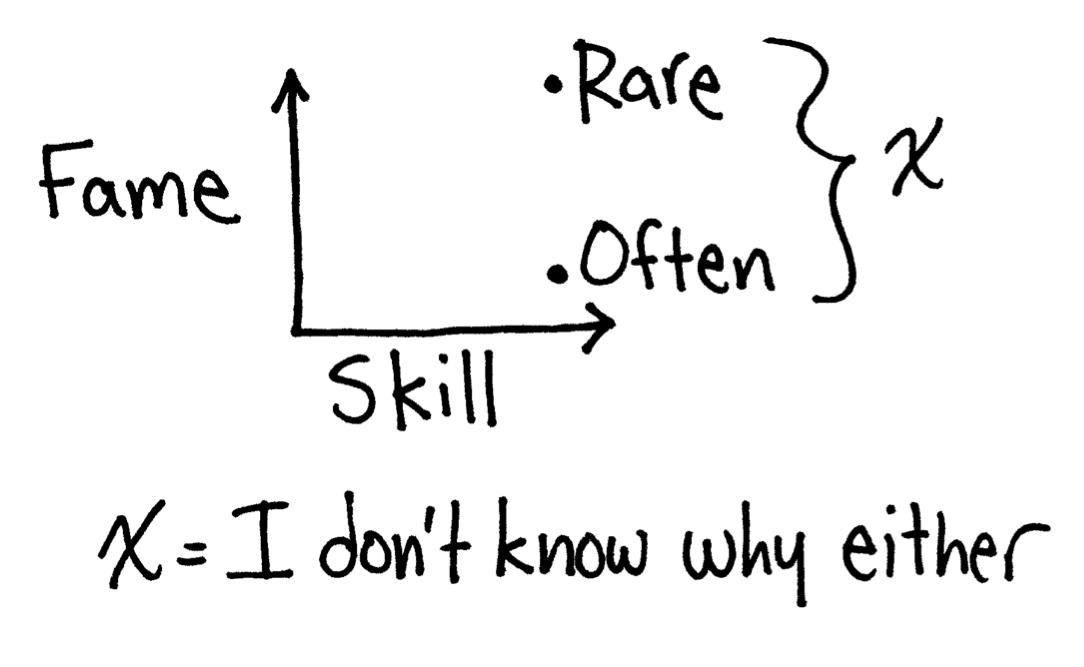

This book is filled with essays written by talented, driven, ~successful~

people. “Successful” gets zazz tildes and scare quotes because honestly, what does “successful” even mean?

To avoid further digression, let’s just stick with a simple definition: ~*~Success~*~ is a state that requires

entry through achievement, the terms of which are entirely subjective. The

people in this book are empirically talented and driven, and are rendered

#successful by some very special magic. I suspect the way most people see it, a

component integral in that magic is financial stability. Lo, the blessed market

has proven that, yes, these people do indeed belong here.

So, how did they get here? And what exactly does “here” look like? Living month-to-month off gigs? Having some savings? A path to

retirement? Accumulated wealth? When are you making enough money doing

something to say you’ve arrived?

On the one hand, this is a great and pragmatic series of questions worth looking

at. On the other hand, I don’t think it’s a topic often spoken about very honestly. And I suspect most of us are

inaccurate with our assessments of the financial lives of those around us,

especially those we look up to. My experience suggests that the stability and

self–support–ability of the successful set is frequently and wildly

exaggerated.

self–support–ability of the successful set is frequently and wildly

exaggerated.

The contours of “here” are different for each person in this book. By and large, we are all still

working at our craft and at our ability to support ourselves. Most of us have

seen some lean months. Why does this matter? Beyond it being true, it’s related to the issue of having time and energy to work on whatever you want to

work on, once you’ve taken care of your finances. The finances of the creative set are generally

not as stable or as verdant as you’d imagine them to be, which means that you might not be as far removed from that

set as you might think.

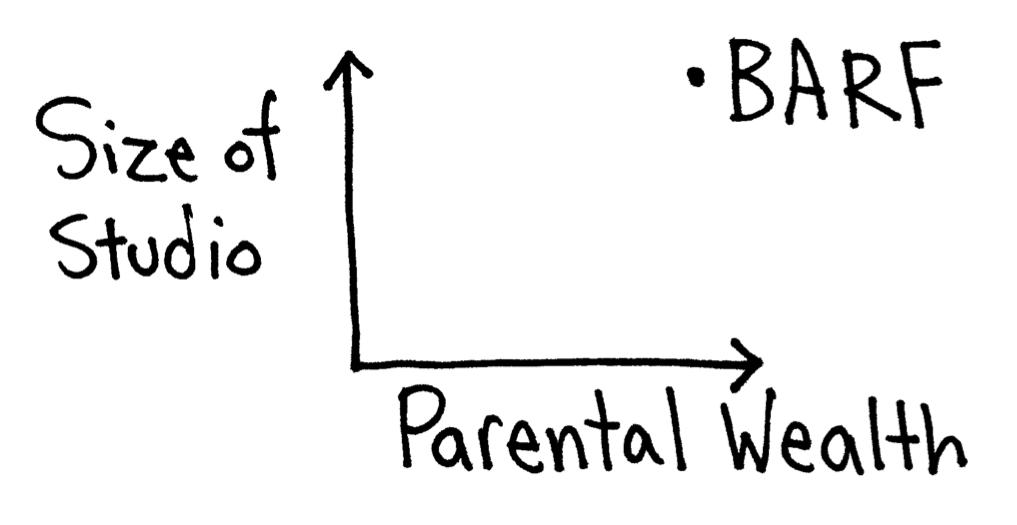

It would be misleading to say this means the only thing standing between you and

having your essay in this collection is being comfortable with unstable

finances. There’s more involved. However, neither privilege nor struggle fully captures the

journey to “here.” The typical journey is part willingness to get by with less at times, part

luck, and part grace—in different proportions for different people.

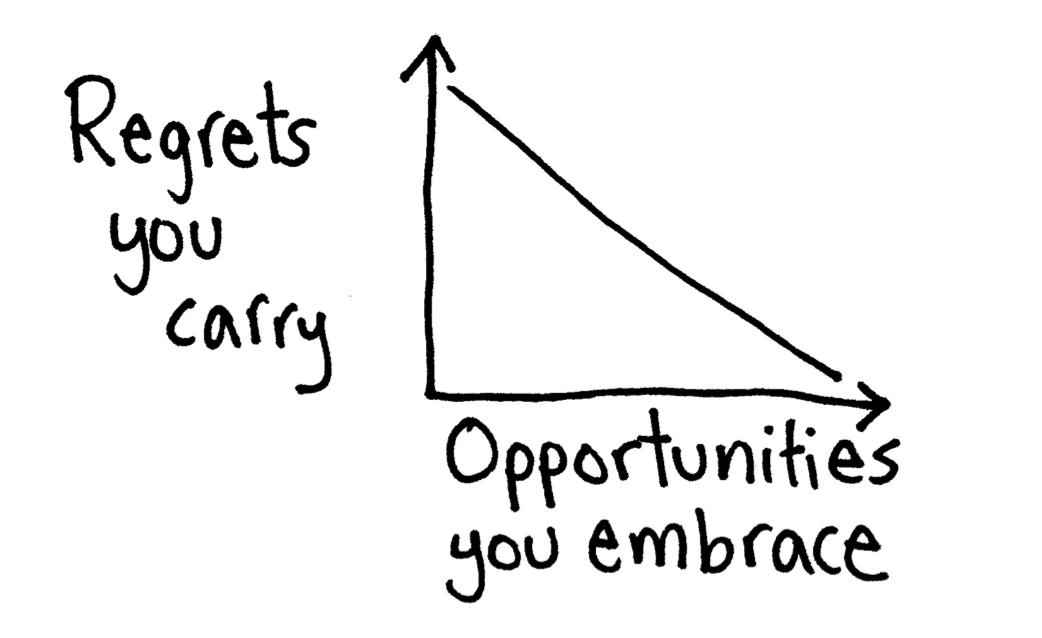

Could you get by with half your current income? Could you get to a place where

you make that much in your dream profession before your runway of savings runs

out? These are the types of questions involved in making “the leap” into the hustle and staying in the hustle, far more frequently than questions

about passion and ability. Most people have passion, and ability can be

enhanced. What gets tested most often is the ability to sit with discomfort and

uncertainty. The skill most used is that of finding different ways to see

progress and success.

What I’m trying to get at is that nobody really makes it to ~*~success~*~. Everyone

rises and falls in patterns throughout their life. Being involved in the hustle

isn’t about arriving anywhere—it’s about being in the mix. Further, the hustle isn’t even about people who are great at being in the mix, who have captured bits of

wisdom and live them, who are financially stable and generally adored. There

aren’t many people like that. So, if you’re in the mix, you are already there, you are successful.

What does this all mean about marshaling the time and energy to work on what you

actually want to work on? It certainly doesn’t intend to ignore that there are people who do not have access to sufficient

time or energy. That is a practical reality and a tremendous challenge to the

spirit—nobody in these positions should be made to feel shame. They are not ignoring

their calling or too scared to take a chance on themselves; they are simply

living their lives responsibly and admirably.

The intention of all this money talk is to suggest that maybe the successful set

aren’t all that far removed from the rest of us. Maybe they don’t actually make that much more money than us, or produce that much more output

than those among us who consider ourselves something, well, less successful.

OK, digression concluded—let’s get back to the second type of hustle: the career of varied projects.

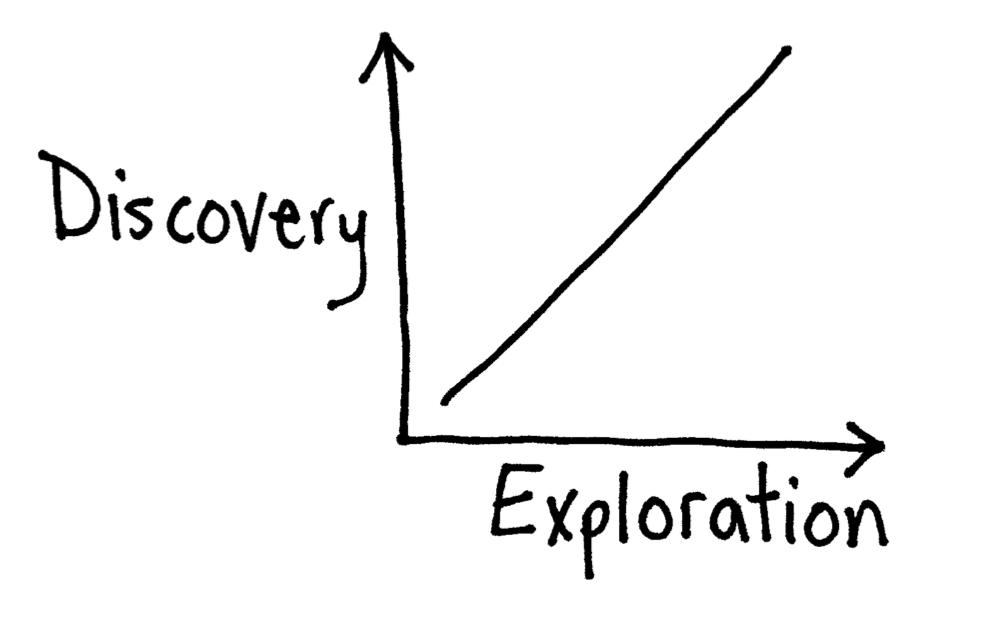

When you aren’t focused in one area, building specific, marketable experience and skill, you

are cultivating another broader skill: getting good at getting good at things.

Climbing a lot of steep learning curves doesn’t so much make you good at all the peaks you reach; rather, it makes you good at

climbing those curves quickly and efficiently. That is your skill as the

broadly interested hustler.

Back to me for a moment, for context. In the last year, as of this writing, I’ve worked on this book, released a free jazz album based on a science fiction

novel, helped produce a friend’s singer-songwriter album, edited a video series of watch commercials, hosted

and edited a podcast, written a screenplay, developed content strategy for a

Fortune 25 company, written a market research report, researched soccer fandom

habits for an Italian soccer club, headed a product team developing a prototype

for a professional networking startup, and curated a blog about charts.

Most of these things I was doing for the first time. There are overlapping

skill-sets and technical knowledge and wisdom I can take with me from one place

to another, but each process was relatively new to me when I set out. And that’s why I do this! That’s what brings me joy. If you are this second type of hustler, this is hopefully

what will bring you joy, too.

The projects I’ve worked on this past year each served a different purpose. Some work makes you

money, some reaches an audience (of peers, fans, whatever), and some you feel

is actually good work, for its own sake. Your favorite projects will hit two of

these checkboxes; the ones you will remember forever hit all three. It’s totally fine doing things that hit only one.

Rather than beat myself up about what any particular project isn’t, I try to ask myself three questions: (1) Did it make me money? (2) Did it

reach people? (3) Did it feel like something I took pride in? This is the sort

of math you do when your career involves doing a little bit of everything you

can.

So now, let’s get down to some concrete advice.

First, get shit done.

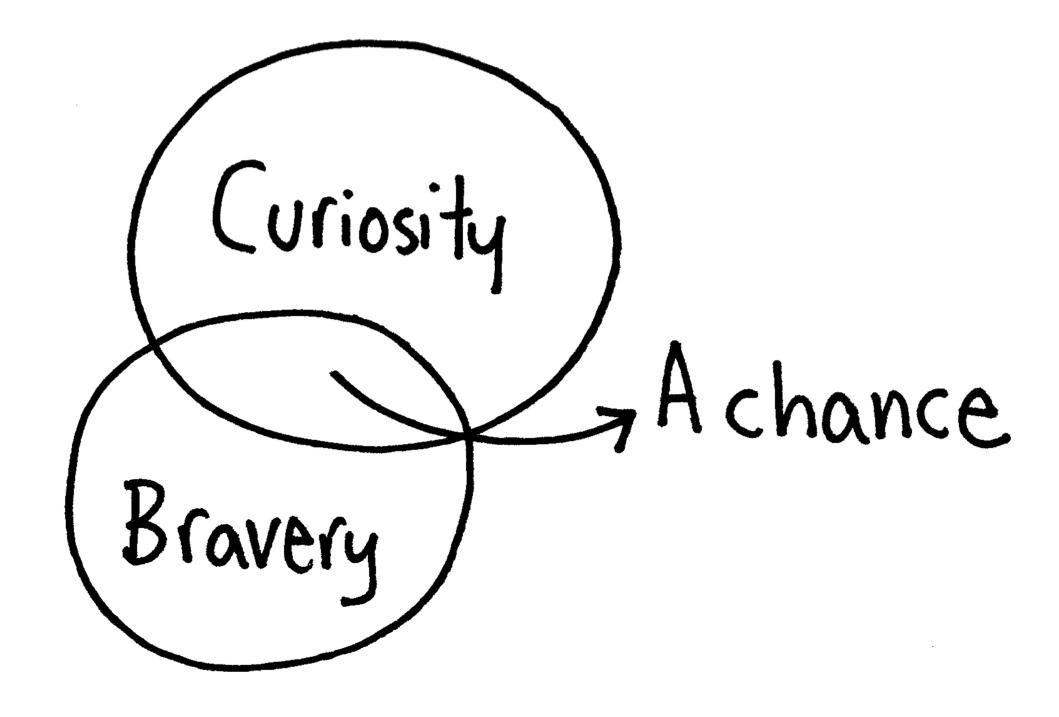

What you make won’t always be good, make you money, or reach your desired audience. But if you

finish it, it will at the very least be done. And that matters. That’s the only way it has a chance of checking any of those boxes. Do things. Do

them until they are done. Then do other things.

Say yes to everything until you have specific experience to call on as to why

you should be saying no. When a good idea comes along, jump on it. And while you’re waiting, make other things—don’t wait around.

As much as possible, embrace that which motivates you to action rather than that

which taxes your energy so much that its toxic energy reaches into other areas.

This includes your projects as well as your business relationships.

Relationships and communities are stronger than individuals, so collaborate.

Invite people into what you are making. Find people whom you think more clearly

or creatively around, and work with them. Find people who are good at getting

things done, and promise each other you will do things. Social pressure works

wonders!

Invest in yourself in concrete ways.

Learn new tangible skills. Invest in the resources around you—new hardware, new software—not extravagantly or without a direction, but with a plan for what you will make

and how it will reward you. To remind you again, the reward doesn’t always have to be monetary. Experience, visibility, résumé material, new relationships, and simple joy are all valid payback for investing

in yourself.

Find patterns.

For whatever reason, opportunities tend to arrive in clumps and dry seasons are

always dry.

Have a relationship with your anxiety.

Like pain, a little bit of anxiety is uncomfortable but is usually there to

help. It can often point you to what you are overlooking or what needs to be

done first. That said, it’s also sometimes totally wrong and unintelligible, in which case tell it to shut

up, and keep moving!

Often your confusion, frustration, ennui, or lack of motivation or creativity is

the gig’s fault more than your own. It can be very difficult to identify when this is

the case. At least be open to the possibility.

Set up your email, to-do list, and calendar.

It’s worth the calories you’ll save later to get this stuff locked down. Try a new system every few months

until something sticks—then reinvent as needed.

Finally, you’re going to fuck up all these rules. Please forgive yourself.

Find a new type of hustle. Make a list of projects

or areas of interest related to what you do

(but not exactly what you do) and that you

haven’t tried yet.

or areas of interest related to what you do

(but not exactly what you do) and that you

haven’t tried yet.

***

Figure out a natural first starting point.

Want to write a book? Write a chapter. Want to start a business?

Make a business plan.

Want to write a book? Write a chapter. Want to start a business?

Make a business plan.

***

Make sure you are able to finish the projects,

even (especially) if they are just for your own edification.

Then, see how taking a bigger bite the next time feels to you.

You might just open up a new area of work for yourself.

even (especially) if they are just for your own edification.

Then, see how taking a bigger bite the next time feels to you.

You might just open up a new area of work for yourself.