OK, I’ve been here before. There’s nothing to worry about, no need to panic. I’m not going to die, right? I’m not going to starve. The last job I had will NOT be the last job I will EVER

have. . . .

But I’m such a failure. All these other people are so good—why can’t I be like them? They evenlook happier. They have it all figured out. What the hell is wrong with me? Who

will hire me again? I’m just not good enough.

I’m not good enough. I’m not good enough. I’m not good enough.

And on and on and on. The phrase repeats in my head like a meditation mantra,

hammering down my ego before the world has a chance to. Who do I think I am,

that I can be something special?

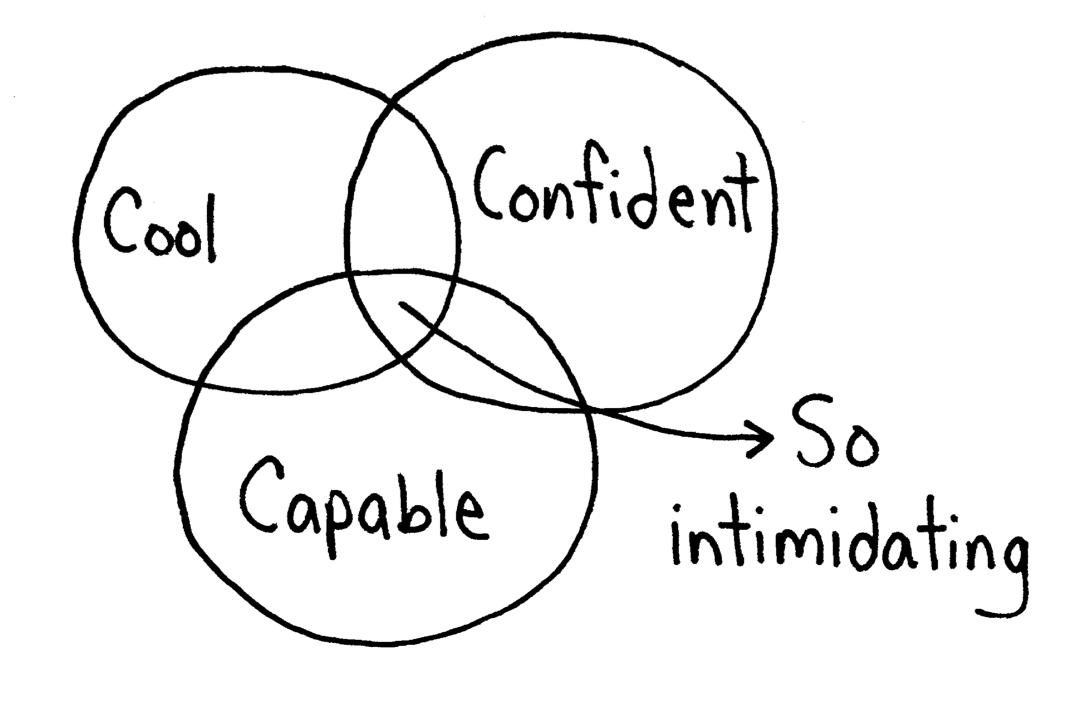

I’m not good enough. The voice reminds me that I’m fooling myself, and only myself, because the world already knows I’m not good enough. I’m not one of them. You know, them—the cool people, the successful people, the ones who have it all figured out.

This is how I spent most of my youth and all of my twenties: fleeting moments of

confidence wrapped in long, drawn-out epidemics of panic and dread.

It started with the cool people at school. I was definitely not one of them, and they made sure to remind me of it every single day: You’re not pretty enough; you’re not cool enough; you’re not good enough. From there, it was just ingrained in me: Some people are cool and have it all

figured out, and others don’t and won’t ever. I was the latter.

I spent most of my life thinking there was a collective they, a group that was a close-knit society that seemed to gather wherever I wanted

to be, physically and metaphorically. I knew in reality there wasn’t any sort of group, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that somehow the in-crowd was everywhere. My fictitious

Illuminati congregated in clubs I was trying to get into, new industries I was

trying to get in on the ground floor of, even in my circles of friends. I could not escape them nor did I want to. I wanted to be one of them. I wanted to have it all figured

out.

What really bothers me now is that in 18+ years of school, no one ever told me

that no one has it figured out—not the cheerleader who gets all the guys, not the guy who gets all the

cheerleaders, not the straight-A student, the valedictorian, the teacher, the

principal, the world-famous rock star, the doctor, the artist, the agent, the

movie star, the author, the entrepreneur—nobody.

As a film editor, I’ve worked intimately with all types of people, from living legends to young

up-and-coming artists. I now know this to be a constant truth: We are all

insecure beings, no matter how successful we are. And I believe the more successful you become, the more

criticism you receive (more people are around to criticize you), and the

greater your insecurity becomes. No one is shielded from it. Some of the most successful people I’ve ever met are also some of the most insecure.

As humans, we are raised to doubt ourselves. It starts the very first time

someone tells us we shouldn’t do something we thought was perfectly fine. It ingrains in us that the rules

and opinions of society are the final judges of our actions, so we must always

look to society for approval. These early interactions teach us that our

instincts may not be trustworthy. In reality, our instincts are what make us

unique, special, and desirable as a human being and as an artist. We should

always trust our instincts, especially creatively.

Had I learned this concept earlier in my life, I could have avoided a multitude

of panic attacks and a fortune in therapy bills. My post-college adulthood has

been a process of expunging everything I learned growing up and erasing all the

negativity and criticism I received as a child.

I grew up a skinny brown girl in a small, primarily white town in New Jersey, in

the 1980s, when there were barely any brown people on TV or in the news. I was

teased for my skin color, my features, and my clothes (which admittedly did sometimes smell like curry). I never had any boy interested in me. I wasn’t invited to any of the cool birthday parties. I was a pariah and I accepted it.

I accepted it for way too long.

Of course, I’m no aberration—everyone has their childhood demons—but we need to recognize that they are just that. And those demons need to be

led out into the light and obliterated.

My life started on a very normal path. I had no idea what I wanted to become, so

I applied to UC Berkeley in the hopes of getting a safety-net business degree

just like my elder sister had. By luck, Berkeley sort of rejected me and sent

me to a community college for my first two years, with guaranteed deferred

admission, barring any academic mishaps.

In community college I stumbled upon a cinema club, where all the students

seemed to be lost souls like myself, who had found a passion for film and were

doing it. People my age were making actual films. Mind you, this was before the

age of cell phones, digital technology, electricity, and cars—well, almost.

In my head, filmmakers were always an exclusive group of highly trained,

innately talented individuals who jumped straight from the womb into the

director’s chair. They were part of the Illuminati. When I realized this wasn’t the case and that this field was accessible to me, I knew I wanted it.

It was love at first sight, and I loved everything about it: the creativity, the group dynamics, the

terminology (like how a clothespin is not a clothespin, but a C-47); it was all

very exciting and self-important. Who doesn’t like saying, “I’m sorry, I can’t. I have to be on set tomorrow”? I felt like an insider at last.

From then on, it was just a bunch of trial and error resulting in plenty of

failure. I became vice president of the cinema club. I bought a super 8 film

camera and a splicing machine. I relinquished my pseudo admission to UC

Berkeley and applied to UCLA and USC film schools. Both schools rejected me for

the film program, but USC accepted me as an undecided, also known as “film-school-in-waiting” because that’s what all the undecided majors were.

At USC, I took every class on film I could and applied again to the film

program. I was accepted as a Critical Studies student in the film school—which was basically

foot-in-the-door-but-still-waiting-for-the-production-program. After all, I wanted to make movies, not sit around and criticize them. So I took

a film class that the dean of admissions happened to be teaching.

Luckily for me it was a small class of about twenty students. Even luckier for me, the dean of admissions offered office hours for her

students, so I scheduled a meeting and told her of my lofty goals to become a

production student and a filmmaker. Now she knew my name, my face, and my

goals. Next semester when I applied for the third time, I was finally accepted as a

Production major, the acceptance letter signed by the very same dean of

admissions. Cue the applause.

In all this time, however, I never recognized that I was hustling. I just had a

goal and I did what I could to achieve it. I also never knew I was networking; I was just talking to people and telling

them what I hoped to do. At school they had always ingrained in us the

importance of networking, which scared me to death. What is networking? How am

I supposed to do it? What am I supposed to say? I had nervous fits at the

thought of Networking with a capital “N.” It took me years to realize that Networking is just talking. It is no more than

that. That’s the big secret. I’m still not the best at it and I hate it abstractly, but most networking events

have free wine and food, so that always helps ease the awkwardness.

I obtained my first job out of college much in the same way. I wasn’t ever really hired so much as I forced my way in (sweetly of course). I was an intern for an editor/director, and she badly needed an assistant but

didn’t know it. After a few months of interning and right before graduation, I told

her that she would lose me as an intern since I needed to get a job, unless she

wanted to hire me because she really needed an assistant. So I was hired. I was

brought in as an assistant editor and as her personal assistant on a

per-project basis. Thus began my freelance life.

When I first started life out of school, a friend gave me a journal as a

present. Inside, he had written out Robert Frost’s famous poem “The Road Not Taken.” That poem became the adage by which I lived. In my moments of hesitation and

doubt, I would open that journal and reread that poem to remind myself to keep

on going.

It’s been fifteen years now and I’m still going strong, but even as I write this, a little voice in my head

whispers, “I hope so.” Thanks, voice, thanks for reminding me you are always there to doubt me.

The voice also brings up a good point: Things never become certain in this lifestyle, but the flip side is that they

also never become mundane. You never know where you are going to be or what you

are going to be working on. I’ve worked in LA, NY, Atlanta, Puerto Rico, Paris, and Morocco, on a train to

D.C., in a Border’s bookstore café, in many a hotel room in random towns, in a mansion in Greenwich, CT, on a

private jet somewhere over the Atlantic Ocean, in a car on the way to the

airport for a flight I was not going on, and at home—lots and lots of jobs from home. So that’s the reward for all the uncertainty—excitement, adventure, and always something new.

The only constant you will have is that little voice. Even though it never goes

away, over the years, you manage to lower its volume and wave it off with a

dismissive laugh. To this day, every time I start a new job or work with a new

client, that voice returns, attempting to remind me: I will fail! I am not good enough. I can’t do this job; this is out of my league. It’s not always easy to let it go or laugh it off, but it’s gotten easier.

I’ve learned to acknowledge this voice as a manifestation of my fear. After fear

comes growth, so it’s good. It means I’m challenging myself with this new project. It means I have to do it because being afraid is never a reason not to try

something. If you don’t have fear, it means you are not pushing yourself out of your comfort zone, you

are not changing, and you are just playing it safe.

Fear can be an indicator of when you need to push yourself harder. When were you

last afraid/uncomfortable? Not recently? Well then, are you really growing as

an artist? No real goals are ever accomplished without fear—it’s a main ingredient. Fear is part of this lifestyle, so embrace it. Take it to

dinner and get comfy with it, because if you want this life, fear is always

going to be there. But just remember that it can also be your best friend.

So that’s it, that’s the big mystery behind the curtain. If you are good at what you do, passionate

about it, and brave enough to stick it out, you will succeed. There will be

many, many moments when you might want to give up and take the easier route,

but don’t. Take the road not taken.

Find your people. Join a group (either online or off)

of like-minded, similarly focused individuals.

of like-minded, similarly focused individuals.

***

Cultivate the interactions and follow up on

conversations. Once you have a few people in

your orbit, invite others in.

conversations. Once you have a few people in

your orbit, invite others in.

***

This group can become the foundation of your

career and some of your dearest friends—but you must make it happen.

career and some of your dearest friends—but you must make it happen.

***

No tribe will form unless someone reaches out

to someone else.

to someone else.