In 1971 one of the architectural surprises of the last century occurred: two young designers, neither French, won the most important commission in Paris since World War II, the design for the Centre Pompidou, and they became famous overnight. The two—a thirty-eight-year-old Englishman named Richard Rogers and a thirty-five-year-old Italian named Renzo Piano—designed an exuberant building that delighted some and outraged others: a glass box supported by a structure of steel and concrete, each façade a playful grid of prefabricated columns and diagonal braces, with a transparent escalator tube that snakes up the front, and other service tubes, picked out in primary colors, that run up the other sides. Imagined as a cross between the British Museum and Times Square updated for the information age, the Beaubourg was immediately popular (it still has more than 7 million visitors a year); plopped down in a broad piazza, it was also populist (Rogers calls it “a people’s center, a university of the street”).1 Yet the project was contradictory as well: a Pop building designed by two progressive architects for a bureaucratic state in honor of a conservative politician (the Gaullist Georges Pompidou), a cultural center pitched as “a catalyst for urban regeneration” (240) that assisted in the further erasure of Les Halles and the gradual gentrification of the Marais. Such tensions have run through the subsequent careers of both Rogers and Piano, who have long identified with the Left even as they have benefited from the patronage of the Center and the Right.2

Centre Pompidou, Paris, 1971–77. Photo © Renzo Piano Building Workshop.

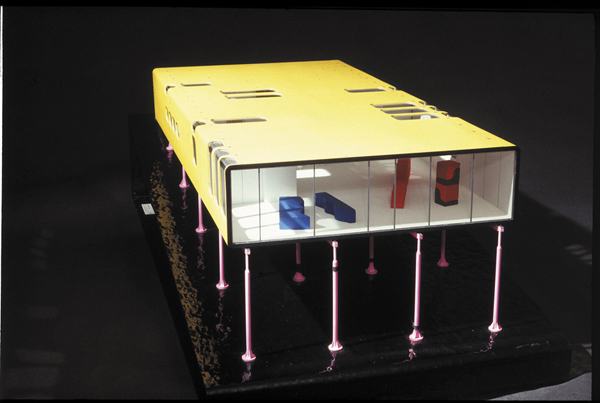

Although young by architectural standards in 1971, Rogers had several years of practice behind him. A graduate of the Architectural Association in London, he attended Yale in 1961–62 with Norman Foster, with whom he partnered, along with their spouses Su Brumwell and Wendy Cheeseman, until 1967. Difficult though it is to believe today, “Team 4” disbanded for lack of work, but not before they completed a breakthrough structure for Reliance Controls in Swindon (in southwest England), which the architectural writer Kenneth Powell describes as “neither a factory nor an office building nor a research station but a combination of all three” (20). The first of many “flexible sheds” that Rogers has designed over the years, the Reliance Controls Factory owed much to the elegant simplicity of the Case Study Houses in Southern California, especially the famous Eames House of 1949. Yet Rogers was also open to the new Pop and high-tech ideas of the 1960s. In 1968, for example, he conceived a mass-produced house made up of yellow panels zipped together and set atop legs that could be adjusted, and so positioned (in principle) almost anywhere. Displayed at the 1969 Ideal Home exhibition in London, the Zip-Up House was, in its high-tech optimism, one part Buckminster Fuller and, in its snappy material and speedy process, one part Archigram (this group had already proposed a sci-fi pod with robotic legs in 1963). However, unlike Fuller and Archigram, Rogers was willing to moderate his schemes in order to get them executed; in the same years, for instance, he built a home for his parents in Wimbledon that combined the Pop modularity of the Zip-Up House with the refined pragmatism of the Eames House. Yet even when large commissions appeared, Richard Rogers Partnership (RRP, now Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partners) continued to experiment with modular designs in search of an economical architecture that was also inventive. Over the years, such schemes have included a mobile hospital for rural use, a diner conceived as an industrial product, an exhibition structure that is a giant system of shelves (a project presented by means of a Meccano model), and an apartment high-rise in which almost everything can emerge from a kit of prefabricated parts.

Given projects like the Reliance Control Factory and the Zip-Up House, the Beaubourg did not come out of the blue; nevertheless, as one of the few prominent Pop and high-tech buildings to see the light of day, it was received as a manifesto. First, it made clear the renewed importance of innovative engineering for contemporary architecture (Rogers and Piano were assisted by the great Irish engineer Peter Rice, who often consulted for RRP thereafter). Second, it offered one response to the open question of what postindustrial design might look like: “Most of us want it to look like something,” Reyner Banham once remarked in a discussion of Archigram; “we don’t want form to follow function into oblivion.”3 In this regard the Beaubourg was not as far-out as the “clip-on” and “plug-in” idiom of Archigram, with its “visually wild rich mess of piping and wiring and struts and cat-walks,” but Rogers and Piano did convey the unlikely mix of the communitarian and the consumerist that came to pervade much 1970s culture.4 Third, and more specific to Rogers, the Beaubourg demonstrated the advantage of mechanical services pushed to the outside of the structure—as a means not only to free up the interior space (at almost fifty meters deep, the open floors of the Beaubourg allow for diverse uses) but also to animate the building as a whole (there is an echo of Futurism here: one thinks of the power stations imagined by Antonio Sant’Elia, with whom Rogers was impressed as a student).5 In a way, the service tubes function as a contemporary form of ornament—they give the Beaubourg both detail and scale—and the movement of people across the piazza into the ground floor and up the escalator not only enlivens the center but connects it to the city as well. (The favored form of architectural imagery at RRP might well be “the mass ornament” of the occupants of its buildings—in circulation, in meetings, and so on.)6

Zip-Up House, 1968.

These are all idea-devices that recur in RRP designs. In effect Rogers presents a threefold motivation of advanced technology in the Beaubourg that continues in work to the present. In the first instance new technologies serve to engineer new kinds of open space, a priority that underscores his commitment to the innovations of modern architecture. Yet the trappings of these technologies are also put to use as ornament, which also speaks to his attention to the motivations of postmodern design. Finally, in the reconciliation of such demands RRP is able to speak to conflictual interests (again, communitarian and commercial, public and private)—a reconciliation that can also be read as a compromise.

After the Beaubourg, Rogers parted with Piano (amicably, as he had done with Foster), and more projects came his way, some from the business establishment. In 1978 no less an institution than Lloyd’s of London selected Rogers to design its main building for insurance trading. The program called for a vast space, dubbed “The Room,” whose functions could expand and contract with trade volume, and Rogers responded with a full-height atrium surrounded by galleries connected by escalators and lifts. Here again services are moved to the exterior, with stairs located in corner towers—the first appearance of this signature feature of the practice. Along with the atrium arch, these stair towers lend a Gothic touch to the Pop look of Lloyd’s; at the same time the stainless-steel cladding connotes high-tech. Although Lloyd’s lacks the populist dimension of the Beaubourg, the fact that a building with Pop-Goth and high-tech attributes could appear at all in the conservative City was a surprise—a provocative one for some.

Lloyd’s established the language that RRP would go on to develop in different ways: an abundance of glazing, services on the outside when appropriate, with stairs and lifts often placed in towers, all done in such a way that interiors might be made as open, and exteriors as animated, as possible. The exteriors of its buildings do not express the interiors in a functionalist way; rather, the office strives to manifest the logic of its designs in a rationalist manner, often through an explicit hierarchy of elements. (Powell suggests that Louis Kahn, who thought in terms of “served” and “servant” spaces, influenced Rogers here, which again speaks to his modern affinities.) For example, RRP uses colors more often than most offices, yet it does so less for Pop effect than for design clarity: it applies its colors rigorously, and usually in order to articulate different services or sections. Although, as the Beaubourg showed early on, Rogers is responsive to the expectations of the capitalist world of mass culture, he also believes that architecture must offer a formal order that might mitigate the distractive clutter of that world.

Lloyd’s of London, 1978–86. Photo © Eamonn O’Mahony.

Lloyd’s was completed in 1986, at a time when conservative calls for the so-called contextualism of postmodern design were strong, and soon enough Rogers was drawn into the fray, sometimes with the Prince of Wales as an antagonist.7 Perhaps these skirmishes impeded further large-office commissions in the London area in the 1980s; in any case, they returned in the boom years of the 1990s and the 2000s. Among these buildings are Channel 4 Television Headquarters near Victoria Station (1990–94); 88 Wood St (1993–99) and Lloyd’s Register (1993–2000) in the City; Broadwick House in Soho (1996–2002); Waterside, the corporate headquarters of Marks & Spencer, in Paddington Basin (1999–2004); Chiswick Park, a business park in West London (1999–2010); and still other projects are in the works. Most of these buildings are cleanly designed and smartly engineered, and each has a flourish of its own—the bridge entrance and the concave front of Channel 4, for example, or the curved roof of Broadwick House. Yet these are more variations than innovations in the established RRP language: again, much glazing, cladding in steel or aluminum when necessary, exterior services and stair towers when possible, and color accents for articulation.

Channel 4 Television Headquarters, London, 1990–94. Photo © Richard Bryant / Arcaid.co.uk.

Patscentre, Princeton, 1982–85.

As might be expected, it was industry, both old and new, that really warmed to the rationality of RRP designs, and such projects also followed on the Beaubourg. In 1979 Rogers designed a center for Fleetguard in Quimper (western France); though a relatively heavy industry (it makes engine filters), Fleetguard received a rather light construction: a long box supported by slender columns that extend though the roof and are stayed by thin cables, with columns and cables painted red. Again designed with the aid of Peter Rice, this steel-mast structure became another signature device of RRP—its most prominent appearance is at the Millenium Dome (1996–99)—but it is not just a stylistic feature: as the stair towers open up interior spaces, so do the mast structures augment interior spans. The result is a functional flexibility that has suited high-tech enterprises as well, such as INMOS Microprocessor Factory in Newport (south Wales) and Patscentre near Princeton (New Jersey), which RRP designed in the early 1980s. These, too, are big sheds supported by steel masts, uniformly colored, that allow for broad spaces mostly free of columns. With much prefabrication and construction off-site, such structures can be built economically and rapidly. Lightness, flexibility, economy, efficiency: these are architectural values, but most companies are pleased to be associated with them as well. In other words, there is an abstract symbolism at work here, and other clients have partaken of it, too (for example, RRP has also adapted its shed type for various academic projects, as with its resource center for Thames Valley University [1993–96]). In all these instances technology serves as both the driver of the spatial arrangement and the source of the iconic power of the building.

As RRP executed these big jobs, it attracted still bigger ones, such as transportation facilities, dockland developments, and master plans. Among its major works in the first category are Terminal 5 at Heathrow (1989–2008), Transbay Terminal in San Francisco (1998–2010), and Barajas Airport in Madrid (1996–2005). Although the primary innovator in this architectural type is Norman Foster—as we will see in the next chapter, his single-level terminal at Stansted established a new model—RRP has contributed as well, and its shed structure finds its apotheosis in such terminals. At Heathrow, RRP used giant tree columns to hold up its broad open terminal; at Madrid many such columns support the long wings of the terminal under a great canopy, colored Spanish red and yellow, whose curves guide travelers like so many waves. (Such neo-Baroque shapes are in fashion in architecture—they serve as one badge of high-tech know-how and style—but Rogers has limited them mostly to roofs.) In other words, both terminals are designed as symbolic gateways as well as practical ones; “like London’s great railway stations of the past,” Mike Davies, a longtime Rogers partner, remarks, “Terminal 5 has a civic role to play.”

Barajas Airport, Madrid, 1996–2005. Photo © Amparo Garrido.

This civic role is important to RRP, and I will query it in this chapter; for the moment it might simply be noted that the office also claims it for its dockland projects and master plans. Over the years RRP has produced schemes for parts of Florence (where Rogers was born), Berlin, Paris, Lisbon, Shanghai, Singapore, and east Manchester, among other cities. But much of its planning has focused on London and environs, with schemes for Paternoster Square (the prince helped to dash this one), Greenwich Peninsula, Bankside, Wembley, and Lower Lea Valley (involving the Olympics master plan); and the same is true for its dock projects, which have included the Royal Albert Docks, Silvertown Docks, and Convoys Wharf. Not all RRP proposals for the public realm are on target: its scheme for the National Gallery extension (1982) foisted its own new idiom—part Beaubourg, part Lloyd’s—on a program and a site not well suited to it. Yet others are inspired, such as the Coin Street Development (1979–83), which proposed that Waterloo station be connected to the City with a lofted arcade and a footbridge across the Thames (fitted with pontoons to support various amenities), and the “London as it could be” project (1986), which argued for a long park along the Embankment as well as a new route from Waterloo station across the river to Trafalgar Square. This kind of will-to-plan is often rejected as a will-to-power, yet it is needed today more than ever, especially as the industrial infrastructure of modern metropolises crumbles and the urban catastrophe of climate change looms (RRP has long studied both problems), and certainly American cities have fallen behind on this score (even at the level of individual buildings, the most innovative designs have lately appeared in smaller cities like Seattle and Cincinnati). In any case, commitment to planning has often led Rogers into the political arena: he campaigned for Labor in the 1992 general election; he was appointed chair of the Urban Task Force after Tony Blair won in 1997; and he has advised design-friendly mayors of Barcelona (Pasqual Maragall, 1982–97) and London (Ken Livingstone, 2000–08) through architectural transformations of their cities.

Of course, proposed projects are one thing, executed ones quite another, and on this score the major public buildings designed by RRP have tended to appear farther afield. A few are law courts, such as the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg (1989–95), which consists of two circular chambers with two long tails for offices and chambers along the River Ill, and the Bordeaux Law Courts (1992–98), a glazed shed with a curvy canopy, under which sit seven courtrooms modeled in the vague shape of wine flasks (unusually for RRP, they are clad in cedar, which reinforces the association) with tops that pierce the roof. Clearly, like other celebrated offices, RRP benefited from the post-1989 push to use architecture to develop institutional images for the “new Europe” (I mean the early, optimistic version of this figure, not the divisive, debt-ridden one on stage since the 2008 crash)—a program in which cities and regions also participated eagerly. On this front Rogers is seduced by the dubious analogy between architectural transparency and political transparency (Foster and Piano are, too—even more so). Thus all the glass at the Bordeaux Law Courts is meant to suggest “the accessibility of the French judicial system” (284); similarly, the National Assembly of Wales (1999–2005) on Cardiff Bay, with its glazed shed under a wavy roof, “seeks to embody democratic values of openness and participation” (319). Yet the structures that house the assembly here—two curvy cones which, as at Bordeaux, pierce the roof—conjure up other associations far more readily: sailboats, church spires, and sorcerer hats à la Harry Potter.

The wine flasks at Bordeaux and the sail spires at Cardiff point to an important question in contemporary architecture: What is the relation between its civic role and its iconic power? Often today iconic buildings are asked almost to stand in for the civic realm, sometimes with the effect that they then displace whatever residues of this realm might be left, as if imagistic promotion were all that citizens can safely expect from politicians and designers today. Rogers, like Foster and Piano (with whom he will always be triangulated), emerged in the interregnum between the engineered abstraction of modern architecture and the decorative historicism of postmodern architecture. In different ways all three designers have refined the former and refused the latter, and for the most part they have fought shy of the sculptural iconicity of contemporaries like Frank Gehry and Santiago Calatrava. However, like these other architects, Rogers and company are also asked to brand their clients distinctively. For example, RRP was commissioned to design a bridge for Glasgow meant to be an “icon for the city,” one that would mark its desired metamorphosis from old industrial center to “European business and cultural capital” (354). The scheme, a ramped promenade that bends dramatically on the horizontal across the River Clyde, evokes a wing, a fin, and a fishnet all at once; here, in effect, an old building-type of function and labor became a new spectacular symbol of leisure and display. Announced in 2003, it was abandoned as a bridge too far three years later.

Bordeaux Law Courts, 1992–98. Photo © Christian Richters.

Such abstract symbolism can be effective, but it can also be inflated; the Millennium Dome qualifies as one such balloon, and it is a colossal one. With its twelve 100-meter masts (twelve as in twelve hours, months, and constellations), “the ultimate inspiration for the Dome,” Mike Davies tells us, “was a great sky, a cosmos under which all events take place” (298). RRP remains proud of this structure, and certainly the office cannot be blamed for its financial problems and confused contents (from its initial smorgasbord of “Millennium Experience” exhibits to its current status as an O2 entertainment complex), but the cosmic association is grandiose, and most people regard the Dome as a white elephant. The RRP contribution to the World Trade Center site was to be a different animal. One tower in a proposed group of four (the others were to be designed by David Childs, Foster, and Fumihiko Maki), the RRP scheme sends mixed messages, with glass façades that extend beyond the rooftop as well as steel cross-braces that support the tower in case its columns collapse in the event of an attack. On the one hand, RRP offers a suggestion of transparency, even of spirituality, which responds to the contradictory rhetoric of American freedom and perpetual funeral that has pervaded Ground Zero discussions since 9/11; on the other hand, it presents an image of security, even of armored defense against the world, also strong in post-9/11 talk. This contradiction comes with the site, and it is compounded by a master plan that mixes office buildings, a transportation hub, retail stores, anodyne cultural centers, and a huge memorial. What designer could make sense of that pseudo-civic realm?

National Assembly of Wales, Cardiff, 1999–2005. Photo © Richard Bryant / Arcaid.co.uk.

Millennium Dome, London, 1996–99. Photo © Grant Smith / View.

For the most part RRP has worked seriously on the question of civic architecture in a consumerist age, and its responses are usually well considered—no more manipulative, on the level of image, than the Bordeaux flasks or the Cardiff spires. Yet here the contradictions that first emerged with the Beaubourg return. Rogers has acknowledged our mass-cultural society with the Pop and high-tech aspects of his architecture (in a sense, RRP holds together the Banhamite and Venturian lineages of Pop traced in the first chapter); at the same time he insists on a humanist notion of the city as “meeting-place.” The rationalism of RRP designs can be severe; at the same time the office is renowned for its sociability (it is structured as a non-profit, with the salaries of its senior partners pegged to those of its youngest employees; it is active in charities; and the famous River Café, run by Ruth Rogers, began as the office canteen). Finally, RRP steams ahead with huge developments; at the same time it rightly promotes the sustainability of architecture and the regeneration of cities. RRP works well with such contradictions, but is that an expression of strength or a function of compromise—or both? To design a public space is not, ipso facto, to work for the public good, and to offer an iconic building is not, ipso facto, to play a civic role. Indeed, it might be that the controversies with the prince, over the Millennium Dome, the Heathrow Terminal, and so on, have the most use-value in this regard: they demonstrate a society that is more antagonistic than RRP otherwise allows.