Has any contemporary architect signed as many cityscapes as Norman Foster? Perhaps none since Christopher Wren has affected the London skyline so dramatically, from the Swiss Re tower in the City to the Wembley Stadium arch to the north. Born in 1935, Foster has a right to be immodest, and he does punctuate his accounts of his buildings with adjectives like “first” and “largest,” and verbs like “reinvent” and “redefine.”1 Moreover, like his colleagues Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, Foster is the subject of recent multi-volume publications, as if to outdo the massive tomes produced for such famous peers as Frank Gehry and Rem Koolhaas, whose large offices are cottage industries compared to his.

For Foster is also “Foster + Partners,” a practice of some 1,000 people in some twenty-two offices. The list of its works runs for pages, and most have been realized: seven banks, nine bridges, eight civic designs (such as the transformation of Trafalgar Square), ten conference centers, thirty-eight arts halls, twenty-eight buildings for education and health, ten for government, fourteen for industry, twelve for retail, thirty-five for leisure and sport, thirty for residences, thirty-nine master plans (from fairs to entire cities), sixteen mixed-use developments, sixty-five offices (for example, Hearst Tower in Manhattan, 2000–06), twenty-eight product and furniture models, nine research complexes, and twenty-four transport systems (from private yachts to train terminals, metro stations, and airports)—and the numbers grow each year.2 Like some of its clients, “Foster” is international in its reach; indeed, many corporations and governments are smaller operations.3 Yet for all the varied work over the last fifty years, the practice has remained mostly coherent in style and consistent in quality. Technologically advanced, spatially expansive, and formally refined, its designs are abstractly rational to the point of cool objectivity, yet somehow distinctive, relatively easy to identify, nonetheless; along with Rogers and Piano, Foster has achieved a global style. No wonder corporate and political leaders seek out this stylish office: there is a mirroring of self-images, at once technocratic and innovative, that suits client and firm alike.

“Foster” offers an architecture of great panache, with sleek surfaces, usually of metal and glass, luminous spaces, often open in plan, and suave profiles that can also serve as media logos for a company or a state. As a result, high-tech and high-design corporations are drawn to the practice: recent commissions include a European headquarters in Chertsey (southeast England) for Electronic Arts, which devises computer games, and a complex in Woking (also southeast) for McLaren Technology, which develops Formula 1 racing cars; both buildings feature glass façades whose elegant curves stick in the mind. That “Foster” is able to design efficient structures that are also media-friendly is proven: Renault uses its center in Swindon (1980–82, in the southwest), with its yellow exoskeleton of piers, cables, and canopies, as the backdrop for its UK advertisements, and the Financial Times has adopted the Commerzbank Headquarters in Frankfurt (1991–98), a towering wedge in white and grays, as its emblem of the city.

In this business of architecture as brand, other famous designers have relied on idiosyncratic forms that brand them as well: to make buildings stand out from often dismal surroundings, Gehry has used neo-Baroque twists, Koolhaas Cubistic folds, and Zaha Hadid Futurist vectors. In comparison, “Foster” favors relatively restrained geometries, however expanded they might be; its two colossal airports in China, for example, are little more than two arrows laid out point-to-point in plan. Such structures read almost as Gestalts or given forms; for the practice this graphic simplicity is all about clarity of program, whereby one might move from taxi or train through checkpoints to plane as though by a natural progression. Even when “Foster” employs irregular volumes—ovoid and elliptical ones sometimes appear, such as the pinecone of the City Hall in London (1998–2002) or the cocoon of the Sage Music Centre in Gateshead (1997–2004)—they are just odd enough to be distinctive, and even then we cannot quite say, for example, whether the Swiss Re (1997–2004) is a gherkin, a bullet, or a (Freudian) cigar. This abstract symbolism is less explicit than the kitschy images of postmodern architecture yet more declarative than the semiotic gestures of deconstructivist design (à la Peter Eisenman, say). All that is certain about this ambiguous abstraction is that it conveys a great faith in advanced technology and international business alike. In the end it is this dual enterprise, which is also abstract and ambiguous in its workings, that the symbolism of such buildings suits and celebrates.

Commerzbank Headquarters, Frankfurt, 1991–98.

Indeed, “Foster” exudes a heady air of refined efficiency that almost any corporation or government would want to assume as its own. The office stresses ecologically sensitive systems as much as technologically advanced designs: clearly it wishes to be seen as both green and clean, which, apart from actual benefits, is good public relations for all concerned. A further attraction is that the copious glass in a typical “Foster” design (not so green, this) suggests a transparency that might be associated with the political or administrative workings of the client—though, as suggested, these workings can be quite opaque. (This is the gambit of the glass dome-cum-observation deck conceived for the refurbished Reichstag in Berlin [1992–99]: it is thought meaningful that German citizens might glimpse their representatives from on high, as though this might nudge the politicians toward accountability.) Moreover, for all its image flair, a primary draw of “Foster” is that it is able to offer a wide array of design services, apparently at any site or scale. A key term for its director is “integration,” that is, the capacity to produce a total design, from an elegant door-handle to a great high-rise, from a private residence for a Japanese art collector to a massive bridge in southwest France. “Design for me is all encompassing,” Foster states (6); and we should take him at his word, for his practice comprehends entire disciplines: architecture, engineering, urbanism, landscape design, product modeling, materials research…4

Reichstag, New German Parliament, Berlin, 1992–99.

At the same time “Foster” does not want to be dismissed as too corporate, with decisions made by committee, or too technocratic, with designs produced by computer, and so the presentation of the office highlights the artistry of Foster the man. Almost every project is published with a sketch or two in his hand, which purports to be the original vision for each scheme. (It is a funny twist: while many artists no longer appeal to the inspired nature of the drawing, many architects still insist on it. They have traded on the old legend of the artist as visionary image-maker—a compensatory myth that continues to circulate with great currency, despite its persistent demystification in postmodernist art and poststructuralist theory alike.) Moreover, Foster asserts a logic of autonomous development that is usually associated with artistic practice more than architectural production. “A number of themes and concerns … have guided us consistently over the years,” he writes, as if momentarily free of context and client alike, and then goes on to trace a pattern of internal “reinvention” of building types (6).

His breakthrough came forty years ago, with the headquarters in Ipswich for the insurance company Willis Faber & Dumas (1970–75; now “Grade One” listed, it cannot be altered). Here three banks of escalators rise from the ground floor, through an open plan, to a restaurant and a garden on the roof, with all elements (including a pool) intended to democratize the workplace. Yet the signature of the building is its pristine wall of dark glass, reflective by day and transparent at night, which curves with the street line: this early interest in spectacular effects has persisted to the present—and perhaps for “Foster,” as certainly for many commentators on architecture, the spectacular is a good-enough substitute for the democratic. (As we saw in prior chapters, this is a trend from the Venturis to Gehry, and it is active in Rogers, too.)

In any case, according to Foster, Willis Faber “reinvented” the office building, and he sees the Hongkong & Shanghai Bank (1979–86), the Commerzbank, and the Swiss Re as successive elaborations of this type at the scale of the high-rise. In these buildings, services and circulation systems are pushed to the perimeter (as often with Rogers), so that the office floors remain relatively open, and lofty atria trimmed with greenery become possible. “What was once avant-garde,” we are told, “has entered the mainstream” (92). The second part is certainly right: such floral atria are now commonplace, but often they appear less as public “gardens in the sky” than as corporate shows of power.

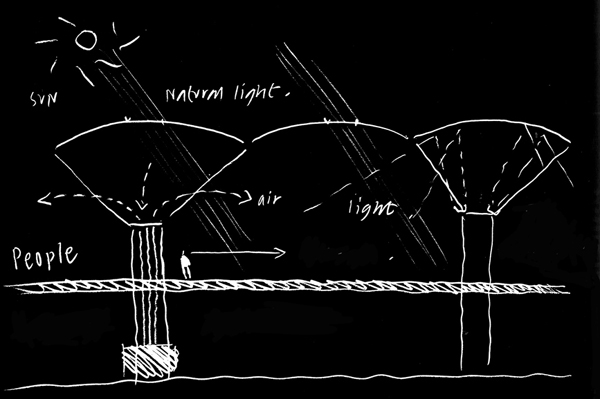

Sometimes a “reinvention” moves from one building type to another. The Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich (1974–78), another early design, also features a “single unified space,” which the practice has “re-explored” in other cultural centers (7). Yet, for Foster, the most significant expression of such space has occurred in three airports: Stansted (1981–91), Hong Kong (1992–98), and Beijing (2003–07). Again, all are open in plan, laid out clearly on a primary level, whose modular canopy guides passengers readily to planes—a model, Foster underscores, since taken up by airports worldwide. (Incidentally, a measure of the technical capacity of the office is that the Beijing airport measures over a million square meters, handles as many as 50 million passengers per year, and was completed in time for the 2008 Olympics.) “With Stansted,” Foster writes, “we took the accepted concept of the airport and literally turned it upside-down” (7). That is, service systems are placed underground, where train transport is also found, not overhead, which leaves the roof free to be a light canopy—another signature device, and one not restricted to any one building type.

Willis Faber & Dumas Headquarters, Ipswich, 1970–75.

In fact unified spaces and light ceilings (most often in glass) abound in “Foster” designs. In renovations of historic buildings, another specialty of the practice, they are used to enclose the extant structure; this is the case, for example, at the Reichstag, the Great Court at the British Museum (1994–2000), and another large courtyard at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington (2004–07). The basic strategy of these designs is to reinstate selected features of the original structure, add circulation systems and amenities, and then to cover the whole with a dramatic glass top. By these means, Foster argues, “new architecture can be the catalyst for the revitalization of old buildings”: “The Reichstag has become a ‘living museum’ of German history,” he claims, and “the Great Court is a new kind of civic space—a cultural plaza—that has pioneered patterns of social use hitherto unknown within this or any other museum” (12, 14). Yet what sort of civic space is projected here, and what sort of social use solicited? For all the reanimation, real or apparent, of either institution, the original structure is treated as a museological object: it is literally put under glass like an old artifact polished up. This combination of historical building and contemporary attraction can tend toward spectacle: a political assembly becomes a spectator-sport at the Reichstag, a distinguished museum becomes its own marvelous display at the British Museum. Is this space civic or touristic, one of social use or mass distraction—or is the distinction now quite blurred?

“Foster” might be more effective when its juxtapositions of old and new are more abrupt, as with the Carré d’Art, a discrete structure opposite the preserved Roman temple in Nimes (1984–93), or a wing of the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha (1992–94), which doubles the Art Deco original nicely. Perhaps the best in this genre, the Sackler Galleries at the Royal Academy of Arts (1985–91), is also the most intrusive; the new spaces are carved right into the old museum, and they do enliven it. Yet this kind of collision has its limits, too. In the Hearst building in Manhattan “Foster” plunged a diamond-gridded glass tower of forty-two stories into the original structure, a low Art Deco stone block on Fifty-Eighth Street and Eighth Avenue, and, far from “floating weightlessly,” the tower looks as though it has crash-landed. Here, rather than the “Mozart of modernism” (as Paul Goldberger proclaimed in the New Yorker regarding the project), he is its Steven Spielberg.

Great Court at the British Museum, London, 1994–2000.

Hearst Tower, New York, 2000–06.

Like history, nature is also sometimes put under glass by “Foster,” literally so in the National Botanic Garden of Wales (1995–2000), which is “the largest single-span glasshouse in the world” (158). As one might expect from the practice, the technology is superb: an immaculate glazing system allows the glass roof to curve in two directions at once, with panes that open and close automatically as the climate demands. Yet what does such a project convey about the status of nature in the “Foster” universe? The office contains a “Sustainability Forum” that investigates new green materials, products, and techniques, and implements them when appropriate: 90 percent of the steel in its Hearst Tower is recycled, for example, and the renovated Reichstag was designed to run an energy surplus. This concern with sustainability is praiseworthy in a world where buildings consume more energy, and emit more carbon dioxide, than either transport or industry. So, too, the practice has long advocated the progressive mixing of postindustrial industries, green areas, and residential developments, as in its plan for the German city Duisburg. There are “no technological barriers to sustainable development,” Foster concludes, “only ones of political will” (15).

The bravado of this assertion is telling. The practice is capable of Promethean interventions into the landscape: for its Hongkong airport a 100-meter peak was flattened, and 200 million cubic meters of rock moved. By the same token, however, nature is abstracted in the “Foster” universe: it has become “ecology,” “sustainability,” a set of synthetic materials and energy protocols—that is, a fully acculturated category. “Foster” frames this acculturation in benign (sometimes Zen) terms, and insists, rightly, on “holistic thinking” when it comes to “sustainable strategies” (14), yet sometimes the holistic slips into the totalistic. Certainly the dialectic of modernity has shown that the prospect of a nature humanized can flip into the reality of a world technologized, and there are indications of this condition already within the “Foster” oeuvre. For example, in 1989 a Japanese corporation asked the office to imagine a satellite extension of Tokyo (this particular topos of visionary architecture runs back at least to the Metabolists in Japan in the 1960s), and its scheme is very sci-fi. A diamond-gridded cone of 170 stories set two kilometers out in Tokyo Bay, “Millennium Tower” recalls, all at once, the Eiffel Tower, the utopian projects of Russian Constructivism (one visualization even includes a zeppelin labeled “Green Visitors”), the dark Deco city of Metropolis, and the gigantic geodesic dome that Buckminster Fuller (a longtime Foster friend) once proposed for midtown Manhattan. In short, Millennium Tower conjures up a total world designed by a brilliant technocrat.

Great Glass House, National Botanic Garden, Carmarthenshire, Wales, 1995–2000.

In such “Foster” designs, both history and nature appear abstracted, even sublimated, and the same might be said of industry. In the background of these projects one often senses the early jewel of industrial structures, the Crystal Palace produced by Joseph Paxton for the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 (names like “Great Glass House” and “Great Court” also point to this precedent). With its efficient construction in industrial iron and glass, its bold reformulation of architecture through engineering, its technological rationalism and social optimism, the Crystal Palace lies deep in the “Foster” DNA: again and again its transparent structure, unified spaces, and undecorated surfaces show through “Foster” designs, and not only in the nearly 50 conference centers and arts halls conceived by the office. (Incidentally, these traits alone suggest that “Foster” has little to do with the scenographic preoccupations of postmodern architecture, though, as suggested, the office finds other ways to communicate.) The Crystal Palace was the confident projection of an industrial Britain still on the rise; against the historical odds, “Foster” attempts a similar projection for a postindustrial Britain, which might be one reason the director is embraced by his countrymen (as Lord Norman of the Thames Bank, no less): as one gazes up at his grand buildings in his homeland, the Empire does appear to live on.

At times “Foster” plays with our threshold-condition between industrial and postindustrial orders: at the Sage Gateshead, for example, the bulge of the music hall, representative of an entertainment economy, echoes the arc of the old suspension bridge nearby, emblem of another economy altogether, but this echo also smoothes over whatever tension might exist between the two. This smoothening is also evident in the other types left over from the industrial era—bridge, tower, train station, underground, airport, department store, and office building—at which the practice excels. With the application of advanced materials and techniques, they, too, appear heightened and lightened—again, sublimated—and this holds for the values that accompany them as well. Functionality, rationality, efficiency, flexibility, transparency: they seem pushed to a new level, and altered in the process, as if they had become emblematic values in their own right.5

Consider transparency. Again, like its modern predecessors, “Foster” suggests an analogy between architectural and political openness, not only at the Reichstag but also at City Hall. (“It expresses the transparency and accessibility of the democratic process,” we are told; “Londoners see the Assembly at work” [188].) Yet the analogy is shaky from the start, and, when applied to the Singapore Supreme Court (2000–05)—“Foster” touts the “dignity, transparency, and openness” of its design (34)—it seems absurd given the track record of that government in general.

How can architects continue to sell this line? Or, more saliently, why do we continue to buy it? Is it out of a sentimental attachment to the old virtues of transparency, and the wistful hope that appearing so will make it so? In any case, such transparency is subject to different interpretations: open office spaces might appear nonhierarchical and democratic to the architect or even to the boss, but panoptical and oppressive to the employees. Then, too, as suggested, what once seemed transparent can now appear spectacular, whereby light and glass no longer signify civic accountability so much as mass attraction. Already, with its glass curtain wall for Willis Faber, “Foster” favored dramatic effects, and this fascination continues through the Reichstag, whose cupola serves as an observation deck by day and a “beacon” by night (182). So, too, the popular Millennium Bridge in London is described as a “ribbon of steel by day” and “a blade of light at night” (204): both a place for viewing and a view of its own, this pedestrian way is a platform for a citizenry imagined as twenty-four-hour spectator-people. In this manner an exhibitionist streak runs through “Foster,” and other prominent practices today as well (Herzog and de Meuron come to mind). A spectacle society invites it, of course, and these architects can hardly be blamed for the society—but must they comply so brilliantly with its problematic desires?6

At issue here is a key ideological dimension of contemporary architecture. Consider how modern architecture of the early twentieth century—the white, abstract, rectilinear variety of Adolf Loos and Le Corbusier—captured the look of the modern. Such architecture still appears modern when almost nothing else of the period does—not the cars, the clothes, or the people.7 “Foster,” I want to suggest, approximates a similar feat for the look of modernity today: perhaps more persuasively than any other office, it delivers an architectural image of a present that wishes to appear advanced. Of course, the very attempt is underwritten by the new-economy clients that the practice attracts—high-tech companies, mega-corporations, banks from Europe to Asia, governments of many sorts—but they are attracted for this reason, too (again, there is a mirroring of images). Now, as with Le Corbusier et al., this look of the modern is not merely a look; it is an affirmation of an entire ethos: if Corb imaged modernity as clean functionality, with architecture as a “machine for living in,” “Foster” updates this image with sophisticated materials, sustainable systems, and inspired schemes, which, again, it offers as values in their own right. In doing so, the office looks back not only to the 1920s but also to the 1960s, that is, to its own point of origin—the late modernism, inflected by Mies van der Rohe, that is associated with powerhouse firms like Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (in the glory days of Gordon Bunshaft), architects like Minoru Yamasaki (of World Trade Towers fame), and designers like Bucky Fuller. Of course, like the 1920s, the 1960s were a moment of technological transformation that generated many visionary proposals—proposals for sleek megastructures among them, most of which could not be executed at the time. Today, however, these projections are no longer so outlandish; in fact “Foster” has realized its own versions of some of them.

One aspect of this look of modernity today is found in the signature element of the “Foster” practice: its diamond grids of glazed glass, “the diagrid.” Although other architects have used it (as Koolhaas did in the Seattle Public Library), the diagrid is an architectural meme for “Foster”: once one looks for it in the work, it appears everywhere. It is a structural unit, but it also serves as an ideological form—one that signals technocratic optimism above all else (in this respect it recalls the prime instance of the diagrid in modern architecture, the famous Glass Pavilion designed by Bruno Taut for the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne). At times in “Foster” this optimism takes on a tinge of faith (as it did for Taut), literally so in its design for a Palace of Peace and Reconciliation (2004–06) in Kazakhstan. A pyramid, clad in stone, whose apex is made up of stained-glass diagrids, this palace is the venue for the “Congress of Leaders of World and Traditional Religions.”8

Koolhaas once suggested that the architectural modernity of Manhattan was driven by a passionate dialectic of two forms that often appeared in its World Fairs—the pylon and the sphere—the first of which attracts us with its height, the second of which welcomes us with its breadth.9 In a sense the “Foster” diagrid is a miniature grandchild of this pair: it can be used in towers (as in Millennium Tower), for it can rise high, as well as in centers and halls (as in the Great Court), for it can also curve and enclose. Yet the diagrid is not a surefire device, for it produces problems of its own, especially ones of scale. Expanded in size, it can threaten to go on forever, as it nearly does in the “Foster” scheme for the World Trade Center, in which a tower of extended diagrids was to top out at 500 meters. So, too, not extended enough, it can appear oddly truncated, as it does in the Hearst Tower.

Palace of Peace and Reconciliation, Kazakhstan, 2004–06.

The World Trade Center scheme is especially telling in this regard. As much as any other candidate for the site, “Foster” appeared to be in synch with the popular (that is to say, the imperial) call to build the towers “higher than before.” Such is its faith in modernity that “Foster” did not alter its design profile after 9/11. Indeed, for all its sensitivity to ecology, “Foster” does not seem much affected by any disaster, natural or manmade; history, too, appears abstracted in its work. In the post-9/11 world this unshakable confidence is welcomed by the shaky powers that be, and, like Santiago Calatrava and a few others, “Foster” delivers it: the office offers moral uplift in beautiful forms at a grand scale. Go, new millennium, “Foster” seems to proclaim with each new project. Go, modernity.