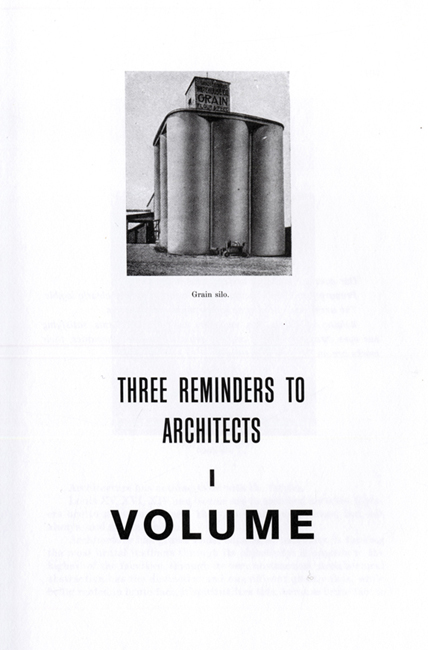

Before Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier ever crossed the Atlantic, they sought precedents for modern architecture in America, and they found them in the grain elevators and daylight factories that lined the old waterways of industrial cities. For the Europeans, these structures were shaped by functional and/or rational criteria alone, or rather they could be made to appear so for polemical reasons; thus, for example, when Le Corbusier published photographs of such buildings, first in his magazine L’Esprit nouveau in 1919 and then in his manifesto Vers une architecture in 1923, he removed ornamental details that distracted from this reading, the force of which, finally, was more stylistic than anything else.1 To look to America for an architectural origin in this way was a kind of primitivism, but it was a kind of futurism, too, for these Europeans also saw the United States as the land of industrial production, which they anticipated as the imminent condition of all modern design. This European America, then, was “a Concrete Atlantis,” a semi-mythical place with a paradoxical temporality (the United States was the oldest country, Gertrude Stein once remarked, because it lived in the twentieth century the longest).2

Page from Le Corbusier, Vers une architecture (1923; English translation 1927). © FLC/ARS.

In the industrial examples singled out by Gropius and Corb there was a tension between the volume of the building (as with grain elevators) and the transparency of its structure (as with daylight factories). This structural transparency was complicated by another transparency, for such buildings were first known to these Europeans through photographs, which dematerialized them somewhat.3 This double tension between materiality and dematerialization runs throughout art and architecture of the twentieth century. Exacerbated by a consumer capitalism that depends on the fungibility of products (often as images), it is pronounced in advanced art since 1960, governed as it is by a dialectic of practices that, on the one hand, articulate bodies and objects in actual spaces and, on the other, play on the effects of media signs—practices that I will simply group under the terms “Minimalist” and “Pop” here. This dialectic remains strong in advanced architecture, too, as practiced by prominent designers informed by this art, such as Rem Koolhaas, Jean Nouvel, Bernard Tschumi, Steven Holl, Richard Gluckman, Yoshio Taniguchi, Tadao Ando, Toyo Ito, Kazuyo Sejima, Peter Zumthor, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron, and Annette Gigon and Mike Guyer. With new light materials and techniques these architects have transvalued the modernist principle of structural transparency, sometimes to the point of travesty.

Already by the late 1920s, the clear exposition of structure and space was deemed the key criterion of modernist design. For Sigfried Giedion such transparency was predicated on long-established technologies of glass-and-steel and ferro-concrete, yet in order to be valued as such it had to await a twentieth-century shift in “the way of living” or Lebensform, as well as a prompt from analogous investigations in other arts (such, for example, was his understanding of the chief motive behind Cubist painting).4 In the same years László Moholy-Nagy conceived transparency as a transformative operation that cut across all the visual arts. Less concerned with structure and space than with light, Moholy urged architecture in particular to integrate the different transparencies promoted by mediums like photography and film. In fact he saw this integration as necessary to the “new vision” of modernist culture at large.5

This technophilic extrapolation of art and architecture did not fare well after the technological catastrophes of World War II, and transparency was no longer an automatic value. In an influential text on the subject written in 1955–56 but not published until 1963, Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky devalued “literal” transparency, in which structure and space are revealed by means of clear glass and actual openings, in favor of “phenomenal” transparency, in which structure and space are rendered indeterminate by means of “Cubist” surfaces and skins that “interpenetrate without an optical destruction of each other.”6 (Note how, even as they also draw on the prestige of Cubist painting, they motivate it in a way different from Giedion, for whom its “simultaneity” of views was key.) To favor phenomenal over literal transparency seems a minor transvaluation, but it marked the moment when, once again in architectural discourse, attention to surface began to be as important as articulation of space, and a reading of skin as important as an understanding of structure. That is, it marked the moment when, at least discursively, postmodern architecture was prepared in its principal version as a scenographic surface of symbols, as practiced by Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown among many others.

Again, Rowe and Slutzky published on transparency in 1963, which was also the moment of the full emergence of Minimalism and Pop. The tension between literal structure and phenomenal effect is central to these practices, too, and it is especially active in the ambiguous afterlife of Minimalism in recent architecture.7 Distinctions are important here. By “Minimalism” I do not mean simple reduction to basic geometries, whether this is brutal or clean in its material expression (examples of both can be found in Ando and Zumtor, for instance) or, indeed, fetishistically elegant (as it is in John Pawson and many others). In my understanding of Minimalism, this initial reduction is performed only in order to prepare a sustained complexity, in which any ideality of form (which is thought to be instantaneous, even transcendental, in conception) is challenged by the contingency of perception (which occurs in particular bodies in specific spaces for various durations). Another formulation of this Minimalist tension is that between the literal structure of a geometric form, say, the recognition of which is on the side of conception, and the phenomenal effect of its multiple shapes from different perspectives, the experience of which is on the side of perception.8 Without this tension Minimalism becomes banal, aesthetically and philosophically—so much “good design” or tasteful décor, which is what “Minimalism” has come to signify for many people.9

For artists like Carl Andre and Richard Serra literal transparency is a matter of production as well as structure; we recapitulate the making of the sculpture as we view the abutted brick units of the former, say, and the propped lead sheets of the latter. This commitment is a modernist one, reinforced by the neo-avant-garde recovery, in the early 1960s, of the materialist principles of Russian Constructivists such as Vladimir Tatlin and Aleksandr Rodchenko.10 In both iterations, Constructivist and Minimalist, this imperative to reveal the process was an imperative to defetishize the work of art, to open it up to public understanding (it is this program, which is at once aesthetic, ethical, and political, that is often reversed in fetishistic versions of Minimalist design). At the same time the Minimalist line of practice committed to literal structure is not immune from the Pop line concerned with phenomenal effect: again, the two are bound up with one another dialectically, and each carries the other within it.11 As we will see in Chapter 10, some bona fide Minimalists like Donald Judd and Dan Flavin are as involved in the phenomenal as they are in the literal, and thus do not fit neatly into either category. The same is true of such architects as Koolhaas, Herzog and de Meuron, Sejima, and Gluckman: in some projects they retain the literal even as they elaborate the phenomenal (often with projective skins and luminous scrims), while in other projects they heighten both elements to the point where they are transformed, confused, or otherwise undone.

In what follows I highlight the vicissitudes of both these dialectics in recent architecture—Minimalist and Pop and literal and phenomenal—largely through a focus on a single institution of contemporary art, the Dia Art Foundation. Other instances might also serve (and I will refer to some in passing), but Dia is the most telling of this aspect of the art-architecture complex. Dia is suggestive, too, regarding greater shifts in this complex, shifts that define its present configuration involving not only an unexpected conversion of functions—of old industrial structures refashioned as new art spaces—but, more importantly, a thorough commingling of once semi-distinct spheres—of the cultural and the economic.

Aerial view of Dia:Beacon, 2002. Photo Michael Govan © Dia Art Foundation.

Upon its founding in 1974, Dia supported a select group of innovative artists like Judd, Flavin, and Walter de Maria, most of whom emerged in the Minimalist break with the traditional parameters of painting and sculpture in the early 1960s. Initially directed by Heiner Friedrich, a German dealer who had exhibited such artists in his galleries in Cologne and New York, Dia was funded by his wife Philippa de Menil, a daughter of Dominique de Menil, the heir to the Schlumberger fortune (made from drill bits for oil testing and digging) and a distinguished patron in her own right (the Menil Collection in Houston was largely her doing). Along with a third collaborator, a young art historian named Helen Winkler, Friedrich and de Menil saw that Minimalist work had opened a structural gap in art institutions: neither private nor public in address, it was beyond the financial means of most collectors as well as the physical limits of most museums, and Dia was one attempt to bridge this divide. Certainly the early projects underwritten by Dia, such as The Lightning Field, a vast grid of 400 stainless-steel poles staked out by de Maria on a New Mexico plain in 1977, were often grand. Even more ambitious was the famous Marfa complex of art that Judd developed, with Dia support, on an old army base in west Texas from 1979 to 1986.

During this time, however, Dia met with economic problems: as the oil crisis deepened in the late 1970s, Schlumberger shares fell, and de Menil struggled to keep Dia afloat financially. Eventually her family intervened, Friedrich resigned in 1985, and Charles Wright, an initiate in contemporary art who was also trained in the law, became the director. Even as he settled with disgruntled artists upset about necessary cutbacks, Wright continued the signature focus on single-artist installations and long-term exhibitions. At the same time he opened Dia to new projects by younger artists (such as Jenny Holzer and Robert Gober) and curators (first Gary Garrels and then Lynne Cooke).12 To this end Wright developed the Dia building on West Twenty-Second Street as an exhibition space, which marked the birth of Chelsea as an art neighborhood; in addition, with the Andy Warhol Foundation, he initiated the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. Both were industrial buildings renovated by Richard Gluckman, who is the architect of the “Dia aesthetic”—which combines a modernist transparency of structure with a Minimalist sensitivity to light and space—as much as any Dia administrator or artist.

Often involved with industrial materials and techniques, Minimalist art was often scaled to industrial space, too. Usually made in old lofts converted into inexpensive studios, it seemed fitting to exhibit this art in these settings as well—that is, in old factories and warehouses transformed into large galleries. In this way, along with changes in zoning laws, the emergence of Minimalism abetted the partial transformation of SoHo from a light-industrial neighborhood into an art-gallery district, and similar areas in some cities also modernized in this manner. In this way, too, the emergence of Minimalism prompted the partial expansion of exhibition formats beyond the given models of the traditional salon and the modernist white cube. Here an early contribution from Dia was its 1978 conversion of a SoHo loft building (c. 1890) at 393 West Broadway, originally a mixed-use structure of retail below and manufacturing and storage above. Gluckman transformed it into an open expanse, punctuated only by its original columns, and to this day it serves as an effective foil for The Broken Kilometer (1979) by de Maria, a floor piece of 500 polished bronze rods two meters in length arrayed in five rows of 100 rods each—that is, in a way that all but measures the space. This reciprocity, whereby the art articulates the architecture even as it is framed by it, soon became characteristic of the Dia aesthetic. Focused on Flavin, the next Dia projects included the conversion of a firehouse in Bridgehampton, Long Island, into an installation space, which Gluckman again rendered as simply as possible. Once more the work punctuates the architecture, yet the fluorescent lights long used by Flavin also produce a colored brilliance that renders the space somewhat indeterminate. As we will see in Chapter 10, Flavin developed literal and phenomenal transparency in tandem, and his example encouraged Gluckman to work toward a similar reconciliation in his own practice. His Minimalist initiation also helped him to resist the blandishments of postmodernism, which were strong in the mid-1980s—and not appropriate to the Dia aesthetic in any case.13

Former Dia Center for the Arts, 548 West 22nd Street, New York. Photo Florian Holzherr.

Walter De Maria, The Broken Kilometer, 1979. Photo Jon Abbott © Dia Art Foundation.

It was at this time that Gluckman converted the Chelsea loft building (c. 1909), also originally of mixed use, into the principal spaces for Dia exhibitions.14 Although built only two decades after the SoHo warehouse, this five-floor structure is more advanced in its engineering, and its reinforced concrete can support a greater span than the wood joists of the SoHo type. This expanse was well suited to installations by artists invited to work there, most of whom were legatees of Minimalism in one way or another. Once more Gluckman opened up the space in such a way as to clarify its structure, and this structure in turn helped to clarify the art; this rapport between art and architecture could be material, formal, tectonic, scalar, or all of the above. By this point such give-and-take had come to define the Dia aesthetic.

In 1989 Gluckman began to design the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, the hometown of the artist. Completed in 1994, this was another conversion of an industrial building (c. 1911), originally occupied by the Frick and Lindsay Company, which supplied machine tools to the steel industry. However, with an auditorium, movie theater, offices, study center, store, and café, the Warhol Museum differed programmatically from the Kunsthalle format of the Dia Center. Of course, Warholian Pop also differs from the Minimalist fare most often associated with Dia; indeed, Warhol represents the other side of the aforementioned dialectic of postwar art, for if most Minimalists play on the repetitive objects of industrial production, Warhol plays on the serial images of mass consumption. Yet, rather than mimic this mediated imagery in postmodern fashion, Gluckman again stressed the structural clarity of the industrial building in a way that set the Warhol representations into relief. Exposing the beams of the ceilings and chamfering the columns of the spaces turned both elements into quasi-Minimalist units that frame such famous sequences as the Elvises (1962–63), the Maos (1972), the Skulls (1976), and the Shadows (1978). To register the uncanny dematerialization at work in the Shadows, say, or to feel the deathly disembodiment in the Skulls, requires the foil of such an embodied space, which is delivered here through both the materiality of beams and columns and the luminosity of scrims and skylights.

Installation of Andy Warhol’s Skull paintings at the Andy Warhol Museum, 1994. Courtesy of the Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh. © 2010 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In 1994 the directorship of Dia passed to Michael Govan, a protégée of Thomas Krens, who was then head of the Guggenheim Museum. By this time Dia had acquired nearly 700 works, including many by artists beyond the Minimalist core such as Joseph Beuys, John Chamberlain, Robert Smithson, Richard Serra, Michael Heizer, Fred Sandback, Robert Ryman, Agnes Martin, Gerhard Richter, Blinky Palermo, Hanne Darboven, and On Kawara. Dia required more space to show this extensive collection—more than a resurgent real-estate market in Manhattan seemed to allow. Govan had worked on Mass MoCA, a project developed by Krens to transform a disused factory complex in northwestern Massachusetts into a contemporary Kunsthalle (it opened in 1999), and with this concept in mind he searched for a similar building within an hour north of New York City. It was found in an old box-printing factory owned by Nabisco (the National Biscuit Company) in a town on the Hudson River called Beacon. Built in 1929 out of reinforced concrete, the structure is a classic factory shed, with many rows of skylights, vast stretches of maple floors, and broad spans between columns—again, the expanse thought necessary to the new scale of art broached by Minimalism—and at 240,000 square feet the exhibition space is enormous. Govan and Cooke renovated the complex with the artist Robert Irwin and the architectural firm Open Office, and the result is the apogee of the Dia aesthetic.

Despite the relative diversity of the art on view (which extends to Fluxus, Conceptual, and site-specific work), certain paradigms basic to Minimalism and Pop dominate. One is the grid, which structures the luminous monochromes by Agnes Martin and the paintings of color bands by Blinky Palermo, as well as the typological photographs of outmoded industrial structures by Hilla and Bernd Becher and the tabulated images of German cultural history (1880–1983) by Hanne Darboven. A related paradigm is the modular unit. As one would expect, this order of “one thing after the other” (as Judd once described it) governs the Minimalist works on view—plywood boxes by Judd, fluorescent lights by Flavin, and open circles and squares cut in immaculate stainless steel by de Maria—but it also informs other pieces such as an impressive sequence of Warhol Shadows, a long row of On Kawara date paintings, and six large panels of dark gray glass by Richter. Of course, the grid and the module pre-exist Minimalism, but Minimalism turned them into a basic syntax for postwar art, and when the art at Dia:Beacon does not conform to these paradigms, it is still informed by them (for example, the enormous geometric cavities by Heizer, the delicate string installations by Sandback, and the torqued steel pieces by Serra).

Gerhard Richter, Six Gray Mirrors (No. 884/1–6), 2003. Dia:Beacon. Photo Richard Barnes.

In principle grids and modules can go on indefinitely, and this serial extension is another factor in the scalar expansion of contemporary art museums. Yet such expansion was compelled by address as well as by seriality and scale: as art after Minimalism pushed further into the space of the museum, in order both to engage the viewer and to articulate the architecture, this space became as important as any wall for painting or any platform for sculpture, and many practitioners became installation artists almost by default. Installation modes still prevail in art today, which is another reason so many large museums have come to exist in the form either of refashioned factories, as at Dia:Beacon, or power stations, as at Tate Modern (or extravagant originals, as at the Guggenheim in Bilbao or the MAXXI in Rome). Yet a circularity has also emerged here, for where artists once turned to industrial spaces in order to exceed the old studio, salon, and white-cube models of artistic production and exhibition, they are now returned neatly to industrial spaces refurbished as Kunsthalles and museums (or, again, to new hangars designed for this purpose). In sum, what was once a tense reciprocity of art and architecture, as in the original Dia aesthetic, has become an elegant tautology, as now at Dia:Beacon, and if this is not quite a reversal, it is at least a containment.

Of course, one can view this arrangement as perfectly fitting: what could be more appropriate, after paintings of modern life in national museums and abstract works in white cubes, than Minimalist installations in industrial sheds? Yet this very decorum is the problem, for it reduces the pressure that the art exerts on the architecture, and one might still hope that institutions would foreground such contradictions rather than design them away. An additional twist appears here, too. With its industrial turn, Minimalism moved beyond the artisanal modes of art still dominant in modernist painting and sculpture, but it also lagged behind the postindustrial trajectory of society at large. The grain elevators that appeared exotic to Gropius and Le Corbusier were familiar to Andre, Serra, and others who grew up in industrial cities in decline. From this perspective industrial production was already touched with the allure of the outmoded (or even the aura of the extinct, which is how industrial structures sometimes appear in the Becher photographs). In short, industrial production was ripe for aestheticization, and at Dia:Beacon this aestheticization is complete (to close the circle, the old Nabisco box factory would only require an installation of Warhol Brillo boxes). Moreover, with the original Dia industrial wealth was converted into cultural capital through artistic patronage (both Friedrich and de Menil were children of machinery magnates); this process is updated at Dia:Beacon, for its primary benefactor was Leonard Riggio, CEO of Barnes & Noble, the book chain that exemplifies the postindustrial mode of extensive marketing, massive warehousing, online ordering, and super-fast delivery. Of course, this condition exceeds any one individual; indeed, it is indicative of greater shifts in the art-architecture complex—here of a depressed working-class area refitted as an art-tourist destination or, again, of old industry recouped as new culture.15

Michael Heizer, North, East, South, West, 1967/2002. Dia:Beacon. Photo Tom Vinetz.

Such contexts damp down the critical charge of the art, again especially in its relation to the architecture, even though this work often remains intense in these settings. Yet this intensity is telling in its own way. Long ago Michael Fried, the great foe of Minimalism, condemned such art as “theatrical,” by which he meant that its move into actual space was also an opening to mundane time (for time is required to experience space in this way), and thus that it violated the distinctive character of visual art not only as strictly visual in nature, but also as nearly instantaneous in reception (“theatrical” implied, too, that Minimalism pandered to its audience with seductive effects).16 However, many installations at Dia:Beacon appear less theatrical than sublime. As in the old Kantian conception, this sublime remains a double movement: the viewer is overwhelmed by immense works in vast spaces, but then recoups this awe intellectually, and so feels empowered by this force in the end.17 One hundred and fifty years ago the Hudson River School of landscape painters like Frederick Church (whose home “Olanna” is not far from Beacon) also produced a pictorial version of this American sublime. Might Dia:Beacon constitute a Hudson River School II, with aesthetic experience reworked as perceptual intensity at an industrial scale?18 This is to suggest, finally, that this art appears oddly pictorial in such settings. Obviously at Dia:Beacon one does not behold a picture of the sublime à la Church, but one does seem to stand within a sublime tableau—several in fact. The pictorialism-writ-large of such installations qualifies the old charge of their theatricality, but, more importantly, it reverses the Dia aesthetic of a tense reciprocity of art and architecture—an aesthetic in which the viewer becomes sensitive not only to the character of each discipline but also to the rapport between the two, and in the process reflexive about his or her own perceptual and cognitive experience.

“Art has no history,” Heiner Friedrich reasserted when Dia:Beacon opened, “there is only a continuous present”; and the art at Dia:Beacon does seem to exist in a perpetual moment of heightened experience, without the pressure of prior art, historical context, or social framing brought to bear on it.19 In general the Minimalist line of art tends to such an aesthetic of presence, which invites modes of exhibition that are also presentist in character. Of course, other factors have contributed to this norm in contemporary display, such as the rise of single-artist installations (in which Dia has played a central role), of private-collection museums, and of pilgrimages to both kinds of sites (Marfa is only the best-known example); all privilege an encounter with a removed aesthetic space over one with a shared historical time. Discussed as a shift from a museum of “interpretation” to one of “experience,” or simply as “the cultural logic of the late capitalist museum,” this phenomenon is familiar by now.20 What goes unremarked is how it has worked its way into modern museums as well, including the flagship of the genre, the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Here I review only a few aspects, pertinent to our discussion, of the latest version of MoMA, which, redesigned by Yoshio Taniguchi, reopened in late 2004 not long after Dia:Beacon. The first point has to do with how the two major architectural divisions in the building inscribe the two major art-historical divisions in the presentation. The core of the museum remains its historical collection of painting and sculpture, presented chronologically on the fifth and fourth floors. These floors divide circa 1940, as do most courses and textbooks on twentieth-century art—a conventional break that accepts the artistic hiatus produced by totalitarianism, World War II, and the Holocaust. Yet these events—political repression, extreme dislocation, and mass death—are not acknowledged as such at MoMA; indeed, its story of twentieth-century art remains so affirmative that this old diplomatic silence, long deemed necessary to postwar reconstruction, is maintained to this day.21

This is the first break remarked by the building; the second is the more salient one here. If the hiatus between prewar and postwar art is bridged too smoothly from the fifth floor to the fourth, the gap between modernist and contemporary art is not bridged at all from the fourth floor to the second: circa 1970 one drops to the cavernous Contemporary Galleries.22 Like other modern museums that seek to comprehend the contemporary, MoMA confronted the predicament of the expanded scale of art after Minimalism, and its response was also to go big—big as in 15,000 square feet with walls twenty-one feet high—even though big does not necessarily mean capacious (in fact big can be inflexible, as the New Museum in New York attests). However one dates the break between modernist and contemporary art, it now seems that such a break has occurred; hence this architectural divide would not be an issue if MoMA did not insist on historical continuity instead.23 For reasons that are both cultural and financial, the museum has opted to stay in the hunt of contemporary art (perhaps it feared it might become a period piece if it did not), so its leaders have reasserted a connection between the modernist and the contemporary, even as its architecture underscores a break—not only in the great gap between the floors but in the different character of the spaces (for example, chronological galleries versus presentist expanse, with a new-media black box on the side). One might go further. In some respects the contemporary has become primary: its galleries are the first we encounter and the largest overall, and the architectural drama of the redesign—the five-story glass curtain wall at the first landing and the vast 110-foot atrium on the second floor—is focused there, too. At least to this degree, the contemporary tail wags the modernist dog.

View of “Contemporary: Inaugural Installation,” the Museum of Modern Art, NY, 2004. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

The second aspect of the new building to underscore concerns its lightness, to which the glass curtain and the grand atrium contribute significantly. The glass shimmers in sunlight, and the atrium prompts one to look up, through the vertical cuts in the white walls, to the floors above; the first effect tends toward dematerialization, the second toward levitation. Brilliantly engineered, the atrium is supported structurally from above; it is thus free of heavy columns, which adds to the quality of lightness. Indeed, with a separation of an inch or two from the floor, the galleries seem to float a little, as this reveal turns the walls into planes that do not appear quite grounded.24 Taniguchi is a master of such light construction, and, as noted in Chapter 4, Terence Riley, then curator of architecture at MoMA, is a champion of this style: he feels such transparency to be both true to the precepts of modernist design and appropriate to the virtuality of our digital world.25 Yet here again a contradiction arises, for, as we have seen, the literal transparency of modern architecture was pledged to structural clarity more than to phenomenal effects. Thus, even though the new MoMA is presented as faithful to the modernist tradition, in important respects it is not; or, rather, if it is loyal, what counts as modernist has changed, and indeed “modernist” here has come to mean “Minimalist,” and both to imply lightness: a sublimation of material and technique, not an exposure; a fetishization of substance and structure, not a defetishization—in short, the near-opposite of what “modernist” and “Minimalist” once meant. In this way, too, the modernist and the contemporary have parted company, despite the stylistic environment of elegant austerity that they now share at MoMA.

Yoshio Taniguchi, the Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium in the David and Peggy Rockefeller Building, the Museum of Modern Art, NY, 1997–2004. Photo © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

In a sense abstraction still rules at MoMA, but it is not the pictorial-spiritual variety, the white-on-white of Malevich or the primary colors of Mondrian; it is architectural-financial. “Raise a lot of money for me, I’ll give you good architecture,” Taniguchi is said to have remarked to the trustees. “Raise even more money, I’ll make the architecture disappear.”26 To make $425 million vanish is an excellent trick. Yet the money does not disappear; one feels its refinement everywhere, and its rarefaction permeates everything. The New York Times celebrated the new MoMA as “a transcendent aesthetic experience”; apparently, in its privileged form of spatial effect, such experience costs a lot. As Koolhaas has remarked, “Minimum is the ultimate ornament, a self-righteous crime, the contemporary baroque. Minimum is the maximum in drag. It does not signify beauty but guilt.”27 In fact, at MoMA as at Dia:Beacon, one senses more pride than guilt, but it is true that their aesthetics of minimum is maximal, the most sublimated of sublimes. Of course, MoMA and Dia:Beacon display far more differences than similarities. In my account alone historical narrative is played down at Dia, and its old reciprocity between art and architecture has become a near tautology; at MoMA, by contrast, historical narrative is foregrounded, and the architecture seems to withdraw behind the art, as if, per modernist belief, it truly were autonomous. Yet the two presentations can also be seen as two parts of the same operation, that of sublimation—one that is at once aesthetic, architectural, and financial.28

Let me draw out a few implications of our discussion thus far. Regarding the Minimalist-Pop dialectic between contrary impulses to materialize and to dematerialize both object and subject, the Pop term has become dominant, as might be expected in a society given over to technologies of image and information. So, too, in the literal-phenomenal dialectic between contrary impulses to reveal and to veil both structure and space, the phenomenal term has become privileged, with the literal sometimes transformed into the phenomenal, which is also often heightened or otherwise intensified. In Chapter 10 I take up some consequences of these developments for recent art; here I want to do the same for recent architecture.

As for the dominance of the Pop term, consider the relevant designs of Herzog and de Meuron, whose interest in both Minimalism and Pop is well known. They apply its idioms cannily: often they use serial units in such a way that material and image are all but conflated, sometimes with materials deployed as images and sometimes the reverse. For example, on the façade of the Ricola Production and Storage Building (1992–93) in Mulhouse-Brunstatt, France, a photograph of a leaf by Karl Blossfeldt (from his 1928 Urformen der Kunst, which sought to disclose the “architecture” of nature) is silk-screened inside plastic panels; and on the exterior of the Technical School Library (1994–97) in Eberswalde, Germany, various motifs based on press photos selected by the artist Thomas Ruff are printed on concrete panels. In such cases, however, the Minimalist-Pop dialectic is not elaborated so much as collapsed—in favor of the Pop term. “The rectangular body of the building is really covered up, almost dissolved,” Herzog and de Meuron comment; “in our work pictures have always been the most important vehicles.”29 At the same time they insist that “architecture is perception,” and, like many architects informed by Minimalism, they speak of their structures in phenomenological terms.30 They thereby suggest that the pictorial and the experiential can no longer be separated and, more, that they embrace this condition. In the world of these architects, then, perception is reduced to the visual, and phenomenology is shot through with pictures.

Herzog and de Meuron, Eberswalde Technical School Library, Eberswalde, 1994–97. Courtesy of Herzog and de Meuron. Photo © Margherita Spiluttini.

As for the dominance of the phenomenal, it often seems to subsume the literal. For instance, the layered glass palisade designed by Nouvel for the Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art (1991–94) in Paris is celebrated not for its quality of transparency but for its effects of “haze and evanescence,” while the double glass façade designed by Herzog and de Meuron for the Goetz Collection (1992) in Munich is said to perform “a complete reversal of the structural clarity of the so-called Miesian glass box.”31 What is literal transparency or structural clarity, these designers ask, when, with synthetic substances and advanced techniques, “the traditional character” of “conventional materials … disappears”?32 If the Cartier and Goetz buildings attest to a reversal of the literal into the phenomenal, other projects effect a blurring of the two, which is often produced through such devices as skins or scrims (or even, as in the Blur Building [2002] of Diller Scofidio + Renfro mentioned in Chapter 6, manufactured clouds). The result here is that surface tends to overwhelm structure (this is also true, for example, in much “blob” architecture and other buildings that privilege the envelope above all else), or, rather, the two combine in the production of atmosphere and affect.33

Sometimes, too, each term in the literal-phenomenal dialectic appears qualitatively transformed, whereby the literal is rarefied as the light (as now at MoMA) and the phenomenal is intensified as the brilliant (as at Cartier) or, conversely, as the obscure (as with the Blur Building). Sometimes the effect here is to dazzle or to confuse, as if the paragon of architecture might be an illuminated jewel or a mysterious ambiance. Certainly such work can be beautiful (this is its great appeal), but it can also be spectacular in the classic sense of Guy Debord: an enigmatic object the production of which is mystified, a commodity-fetish at a grand scale. Here light is transvalued once again: if modernists celebrated it as a medium of utopian spirituality (as in the Glass Chain circle of Bruno Taut) or as a figure of technological progress (as with Moholy), light is now largely put in the service of enigmatic and/or special effects.34 Implicit in this architecture of lightness is that transparency, whether desired or not, is impossible in a world given over to the commodity-form—that is, where the workings of most things are so many black boxes. “I could not understand objects I used daily: the TV, the refrigerator, the personal computer,” Herzog commented as early as 1988. “All these objects seem to me to be a kind of synthetic conglomeration…They are in a way so mixed with other materials that decomposition back into the original form is no longer possible.”35 If this is true of a refrigerator, how much more so of a contemporary building? Rather than resist this condition, this line of thought seems to run, why not make a virtue of it somehow? The argument leads one, as it has led Herzog and de Meuron, to advocate an architecture not merely of surface over space but of the two conflated as “surfaces for projection.”36

Jean Nouvel, Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art, Paris, 1991–94. Photo © Ateliers Jean Nouvel.

In 1963 Rowe and Slutzky wrote of the “equivocal emotions” that a play between literal and phenomenal transparency might provoke, an equivocation that can be reflexive, even critical, in effect. However, what the triumph of the phenomenal often produces is less equivocation than suspension—of a subject “suspended in a difficult moment between knowledge and blockage.”37 This outcome sounds harmless enough, yet what is this “difficult moment,” structurally, if not one of fetishization, which holds the subject between a recognition of the real and a refusal of it, precisely between knowledge and blockage? As with the commodity fetish, such designs as the Tate Modern Project proposed by Herzog and de Meuron might mystify us with “surfaces for projection”; and as with the sexual fetish, they might offer an intensity of affect but at the possible cost of psychic and/or social arrest. Of course, one could argue, it is exactly architecture like this that is most appropriate to contemporary subjectivity and society. Not only does architecture as projection suit a subject given over to the visual and the psychological, a subject defined in terms not of the complexities of the phenomenological but of the vicissitudes of the imaginary.38 But an architecture of “equivocal emotions” also suits a society pervaded by “cynical reason”—that is, by a self-protective ambivalence that is not “false consciousness” so much as it is sophistical indifference (“I know the rich have interests opposite to my own, but nevertheless I will identify with them”).39 Here again, however, it is this very decorum that is the problem—and why, in any case, would one advocate an architecture that further privatizes the subject and occludes the social?

Herzog and de Meuron, Goetz Collection, 1989–92. Munich. Courtesy of Herzog and de Meuron. Photo © Margherita Spiluttini.

At stake here are not mere preferences in design but important implications for subjectivity and society alike. Perhaps the rationalist subjectivity assumed by literal transparency—a subject invited to understand space, to critique architecture, to defetishize art and culture—is a fantasy of its own, another myth of Enlightenment in need of demystification. Yet what are the alternatives advanced in recent architecture? Pastiche postmodernism à la Venturi positioned the subject as the master of architectural history, able to cite its styles at will, even as it also presented this subject with amnesiac simulacra. Conversely, deconstructivist postmodernism à la Eisenman positioned the subject as the object of architectural language, even as it also allowed this subject a delusory degree of agency in its manipulations. The subject interpellated by the architects under discussion here is different again—once more, a subject suspended in a difficult moment between knowledge and blockage. Again, it might be that modernist transparency mystifies more than it demystifies, that it cannot reveal the technological basis of a contemporary building (or anything else) in contemporary society. But is this pretext enough to produce an architecture of obfuscation, one that tends to reinforce a subjectivity and society given over to a fetishism of image and information? In our present of ever-greater financial, corporate, and governmental black boxes, transparency might be a value to recover.

Herzog and de Meuron, The Tate Modern Project, London, 2005–. Image © Hayes Davidson and Herzog and de Meuron.