[6] Asian European Encounters, 1509–1688

The Euro-Chinese Cities

As we saw in Chapter 4, cities set the cultural and political pattern of the long sixteenth century. Among them, the cities refashioned by European conquerors after 1511 were relatively small and culturally marginal, but nevertheless revolutionary in the three new elements they introduced. They were strongly fortified against a hinterland presumed to be hostile; part of an international network of posts all subject to the same authority; and governed by regularly replaced administrators. These factors combined to provide a relatively stable environment in which commercial considerations were usually paramount, thereby minimizing the perennial Southeast Asian risks to traders of tyranny on one side or anarchy on the other. In many other respects, however, these new cities continued the commercial techniques and ethnic complexities of their forebears.

The successful formula was certainly not discovered overnight, and it was as much due to good luck as to good management that it was found at all. The Portuguese introduced in the period 1500–25 a chain of conquered and fortified posts along the major arteries of Asian maritime commerce, but they notably failed to attract a major share of the Asian trade to these centers. Titling himself “Lord of the conquest, navigation and commerce of Ethiopia, India, Arabia and Persia,” King Manuel I (r.1495–1521) sought the military destruction of the hitherto largely unarmed Muslim commerce of the Indian Ocean, and its replacement by a Portuguese state monopoly of the key items of trade. Afonso de Albuquerque was responsible for the seizure of the three key ports of Goa (1510), Melaka (1511), and Hormuz (1515).

In Southeast Asia, where Portuguese power was always more tenuous than in the Arabian Sea, Melaka was the only major stronghold, though forts were also episodically maintained in Ternate from 1520 and in Ambon, Solor, and Timor from mid-century. Given the belligerence with which the Portuguese had set out to attack Muslim shipping, the Muslims who dominated the Indian Ocean trade had little appetite to settle in these fortified settlements even on the occasions they were admitted. On the contrary, they specifically sought out alternative ports strong enough to confront the Portuguese. The attempt to monopolize trade in the hands of the Portuguese crown or merchants licensed by it was counter-productive. The Portuguese made their largest profits where they were too weak to contemplate these monopolies, particularly in their easternmost footholds in Macao and Nagasaki.

Portuguese Melaka contained only a fraction of the population or the commerce of its Malay-ruled predecessor. The military resources of the city depended largely on its Portuguese or mestizo population, never amounting to more than a few hundred. Portuguese policy encouraged soldiers to marry locally, Christianize their local wives, and become permanent householders (casados). Even at its height, around 1612, there were only 300 such casados living within the fortified city along with 7,400 Christianized Asians mostly living outside the walls, alongside a probably smaller number of Hindus, Muslims, and Buddhists. The Muslim Malay population of Melaka’s ruling group had largely moved out at the conquest, along with the Indian Muslims. The Javanese, the largest ethnic component of population under the Sultans, also soon fell out with the Portuguese and had gone by 1525. The Asian population that did eventually assemble in Melaka was predominantly of non-Muslim Indians, Chinese from Fujian (particularly after 1567), and a variety of Southeast Asians who had had dealings with the Portuguese.

Chinese trade with Southeast Asia changed fundamentally in 1567, when for the first time scores of private junks were annually licensed to trade southward. Whereas in earlier periods Arab or Southeast Asian ships had been responsible for a large portion of China’s maritime trade, between 1567 and 1840 this was overwhelmingly in the hands of Chinese ships, mainly based in Fujian. In this period, European ports would become so heavily reliant on the visits of Chinese ships, and the admission of skilled Chinese migrants, that we may reasonably label them Euro-Chinese cities.

Manila was the first of the European settlements to profit from this influx, and remained for its first two centuries absolutely beholden to it. This boon was pure good fortune for the Spanish. The friars and conquistadors sent westward to claim the Philippines for Spain in the 1560s were thinking of spices and souls, but had virtually no idea of the potential of trade with China. Their commander, Legazpi, soon became aware of the thriving port of Manila and of the rich Chinese trade that had begun to focus on it. The expedition he sent to reconnoitre it in 1570 found four Chinese ships anchored off the Muslim-ruled trading settlement, and had the wit to treat them well. Once Legazpi moved his capital to Manila in 1571, the ships from Fujian came in ever-greater numbers, for the Spanish had what the Muslims had not – a steady supply of cheap silver from the mines of Mexico and Peru. By 1575 there were fifteen ships a year arriving, and the colony’s economic viability was firmly established. Chinese silks and porcelains were sent to Acapulco on the returning Spanish galleons that became Manila’s lifeline to Mexico.

With one of the best natural harbors in the world, Manila became, almost despite itself, the biggest Southeast Asian market for Fujian traders between 1580 and 1640. It thereby provided a magnet for Japanese traders (banned from direct access to China) to obtain the silk and other goods they needed from China. Manila was also their most popular destination until surpassed by Hoi An (the port of Cochin-China) around 1610. Distinct Chinese and Japanese communities developed in the city, and the craftsmen brought there to service the needs of Chinese traders soon became indispensable to the whole city. Governor Ronquillo, in 1581, first assigned them a specific district and silk market, the parian, just east of the walled city on the south bank of the Pasig River. Though burned down seven times between 1588 and 1642, it was regularly rebuilt more handsomely. Ronquillo also began the lucrative practice of taxing the Chinese, imposing an initially moderate 3% tariff on all goods imported from China, later raised to 6% in 1606.

Bishop Salazar, who adopted a protective stance toward the Chinese residents in the hope of using them for the conversion of China, commented in 1590 that:

This Parian has so adorned the city … that no other known city in Spain or in these regions possesses anything so well worth seeing as this; for in it can be found the whole trade of China, with all kinds of goods and curious things which come from that country. These articles have already begun to be manufactured here, as quickly and with better finish than in China. … They make much prettier articles than are made in Spain, and sometimes so cheap that I am ashamed to mention it (Blair and Robertson 1903–9 VII, 224–5).

Others were more critical, complaining that Chinese industry caused both Spanish and Filipino inhabitants to abandon whatever skills they had and leave craftsmanship to the Chinese. The sheer dependence of the Spanish colony on Chinese enterprise gave rise to fears that bordered on paranoia, frequently endangering the whole enterprise. A city census of 1586 showed already 750 Chinese shopkeepers, and a further 300 craftsmen with an amazing range of skills, while there were only about 80 Spanish citizens, 200 Spanish soldiers, and 7,500 Filipinos outside the walls. There were reported to be 20,000 Chinese residents in Manila in 1603, when mutual suspicions got out of control and the Spanish, Japanese, and local populations joined a ghastly pogrom which killed three quarters of the Chinese. Although the bloodthirsty victors were rewarded by the distribution of 360,000 pesos’ worth of Chinese trade goods, “the city found itself in distress, for since there were no Chinese there was nothing to eat and no shoes to wear” (Morga 1609/1971, 225).

The China-based trade was uninterrupted by these grisly events, and the population quickly built up again despite oft-repeated regulations to limit Chinese migration. In 1640 there was another horrific pogrom in which 20,000 Chinese were thought to have been killed, and in 1662 yet another. Thereafter Spanish vigilance and the declining fortunes of the city combined to prevent its Chinese population from growing beyond about 20,000, still always far outweighing the Spanish. By the 1660s about a quarter of the Chinese were Christian, most of them married residents. Their Filipina wives deserve more credit than they have been given for integrating the Chinese into a Southeast Asian society.

Piracy, smuggling, and the constant wars with the Dutch between 1609 and 1648 took a big toll on the glittering profits of the Manila galleons and the Chinese ships that supplied them. Nevertheless, the number of Chinese ships reaching the port seldom fell below twenty a year before 1644, when the fall of the Ming Dynasty ended the golden age of Manila by reducing the flow to an average of only seven a year. The crown sought to impose a limit (permiso) on the value of the cargoes sent annually to Acapulco in the two licensed ships, in order to protect Spanish silk manufacture and to limit the outflow of silver from Mexico. In 1593 the permiso was first set at 250,000 Spanish dollars’ worth of purchases in Manila, or double that amount of sale value in Mexico. This was raised gradually to 500,000 in 1734 and 750,000 in 1776. Since this limit was always exceeded, the Manileños had an interest in not recording the real amounts. About two million Spanish dollars must have been carried to Acapulco each year in more prosperous times, such as the 1590s and early 1600s, and again periodically after 1690.

The Dutch Company (VOC), profiting from Spanish and Portuguese experience, set out far more deliberately to establish an entrepôt that would attract Chinese and Southeast Asian traders. Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1587–1629) was the most determined advocate of establishing a Dutch stronghold at a strategic place, and he eventually found it at Jakarta. A site adjacent to the Sunda Straits between Sumatra and Java was ideal for the Dutch strategy of approaching the Spice Islands not through India like the Portuguese, but directly along the roaring forties of the southern Indian Ocean and then northward to Java. This territory was dominated by Banten, at whose capital both Dutch and English first made their eastern base. Jakarta was a weaker eastern dependency of Banten, and Coen managed to conquer the small town in May 1619. There he built a fort that would withstand all conceivable attacks and laid the basis for an Asia-wide trading strategy.

Coen renamed the city Batavia, and envisaged it as the principal site in Asia for solid Dutch householders and private traders, on the model of Portuguese casados, who would defend the settlements without the need for expensive professional soldiery. However, European women were almost never sent to the east. The VOC sent 978,000 men to Asia in the period 1602–1795, of whom only a third ever returned, against a few hundred women in one failed experiment. Dutch mores were less accommodating than Portuguese (and much less than Chinese) to intermarriage with Asians, and the Company’s shareholders opposed the idea of sharing its lucrative monopolies with private traders. When the city faced its gravest hour against the attacks of Mataram in 1628–9, it was defended by only about 230 Dutch “citizens,” as against 470 Company soldiers, 700 Chinese residents, 260 Company slaves, and 200 slave-descended Christian freemen (mardijkers) and Japanese. The Dutch-speaking Protestant European and mestizo communities declined steadily in demographic significance as the city grew, until it was less than 1% after 1770, but their economic and social position as a pampered and powerful endogamous elite was steadily enhanced.

To a far greater extent than the Portuguese or Spanish, the Dutch relied on slaves from eastern Indonesia, southern India, and Arakan as a labor force and female population for their early Asian cities. At the 1632 enumeration there were 2,724 slaves in the city, a third of the population, in addition to 495 mardijkers, some of whom already had their own slaves. Most slaves then belonged to the Company, working in the warehouses and on building sites, but already there were 735 belonging to Dutch citizens. After initial difficulties in finding supplies, Batavia from 1660 to 1800 became much the largest importer of slaves in Southeast Asia. About 500 a year were introduced in 1660–90 and the number rose to about 4,000 during the eighteenth century. The great majority were purchased in south Sulawesi, Bali, and the islands further east. Slaves in the city (both inside and outside the walls) numbered over 30,000 in 1729 despite enormous mortality and the manumission of a high proportion of second-generation slaves. The numbers were even higher in the eighteenth century, though as a proportion of the total population they dropped to a quarter. By then slaves were no longer of great significance as a labor force, becoming overwhelmingly domestic and largely related to the needs of the European elite for status and of the disproportionately male population for sexual partners.

Although Coen’s policy for Dutch settlers was a failure, his other strategy proved its salvation both in the short and the longer term,

to establish a place where so great a concourse of people would come to us, Chinese, Malay, Javanese, Klings and all other nations, to reside and trade in peace and freedom under Your Excellency’s [VOC] jurisdiction, that soon a city would be peopled and the staple of the trade attracted, so that [Portuguese] Melaka would fall to nothing (Coen 1616, in Coen 1919 I, 215).

It was particularly Chinese settlers and Chinese trade that Coen attempted to lure or bully to Batavia from the moment of the city’s foundation. He once threatened that no Chinese junk would be permitted to leave Batavia for China until it had provided 100 men for the city.

Before the end of 1619 more than 400 Chinese had made the move to the new city, providing its first labor force before the advent of significant numbers of slaves in 1623. By 1632 there were 2,390 Chinese in the city and they furnished 45% of the free adult male population. As in Manila, they were engaged in service industries, construction, craft production, and provisioning, as well as trade. Unlike Manila, however, the Chinese did not need to become Christian to be trusted, but were encouraged to maintain a distinct identity under their own Dutch-appointed leaders. So Bingkong was already made head (later Captain) of the Batavia Chinese in 1619, and his authority was reinforced with the right to certain monopoly revenues in what became an entrenched pattern of Sino-Dutch economic organization. He farmed the right to run the city’s weighing-house from 1620, while another prominent Chinese, “Jancon,” took the lucrative monopoly on Chinese gambling. By mid-century, Chinese operated the lion’s share of the revenue farms in Batavia and other Dutch cities, including port duties, and the revenue they thereby generated represented a quarter of total VOC income in Asia, second only to VOC trading.

The disruption caused by the fall of the Ming Dynasty (1644) and the 30-year struggle thereafter for control of China’s seaboard put a damper on Chinese trade and emigration to Batavia. The four to five junks that had annually visited Batavia from Fujian ports in the 1630s dropped to almost nothing. In the 1670s a trickle of Fujian junks began to rebuild the trade connection, but only in 1683 did the Manchus sufficiently control the Fujian coast and Taiwan to allow normal trade. Chinese vessels poured southward from Xiamen (Amoy). Batavia became their most important foreign destination after Nagasaki (Japan’s only open port), with an average of fourteen large junks a year arriving throughout 1691–1740. The Chinese population of the city built up quickly to 14,800, or 17% of the population, by 1739. Given the large numbers of increasingly unproductive slaves, this was the most valuable population group in the city, responsible for most of the manufacturing, construction, and service industry, as well as sugar milling and market gardening.

Indonesians, and especially Javanese, were initially distrusted by the Batavia administration as potentially hostile, and it was only in the 1650s that they began to feature significantly in any but the slave categories. Batavia, unlike Manila, began as an enclave economy entirely provided by sea. The most economically important of the Southeast Asian categories in the seventeenth century were Muslim Malays, an essentially diasporic trading community having its roots in the former emporia of Melaka (before 1511), Patani, Johor, Makassar, and Palembang. The office of Malay Captain was established in the 1640s, and its first three occupants were all wealthy merchants from Patani. The Malay group numbered 2,000–4,000 in the period of the city’s commercial apogee between 1680 and 1730, and was the most important ship-owning community after Chinese and Europeans, with ships double the size of other Indonesian craft.

Javanese farmers began to be tolerated in the outer districts in the latter decades of the seventeenth century and to provide the city with some of its food needs, while a growing number of Islamized Balinese ex-slaves assimilated with them. By the end of the century this was the largest single ethnic category in Batavia, which was beginning to lose its enclave quality. Growing beyond 100,000 in the 1720s, Batavia’s population nevertheless remained modest in comparison to the extraordinary reach of its commercial transactions throughout maritime Asia. It was not the largest of Southeast Asia’s cities during its heyday in 1650–1740, but certainly the wealthiest and most strategic. It was a hothouse of cultural interaction and mutual learning.

Women as Cultural Mediators

The exclusively male traders, sailors, and soldiers who came to Southeast Asia from elsewhere before 1800 formed mutually beneficial partnerships with Southeast Asian women. The open and cosmopolitan nature of the ports gave wealthy long-distance traders high status as sexual partners, and particular value for women accustomed to dominating most areas of their own markets. Rather than the prostitution practiced in other areas, Southeast Asian ports offered the visiting trader the much more valuable opportunity for a temporary marriage, which

lasts as long as he keeps his residence there, in good peace and unity. When he wants to depart he gives her whatever is promised, and so they leave each other in friendship, and she may then look for another man as she wishes, in all propriety, without scandal (van Neck 1604/1980, 225).

The more balanced power equation between women and men Below the Winds encouraged serial monogamy and easy divorce for both parties. The Asian outsiders – Chinese, Indian, and Muslim – had little difficulty fitting this pattern into their concept of polygyny, with a different wife in every port. European Christians had more difficulty accepting the system without guilt or scandal, but wherever individual Europeans escaped the social control of their home community they found the system congenial. Hybridity was therefore the norm for these cities, up to the point when communication with the homeland became so well established that its prejudices were imported. In the nineteenth century such interracial unions came to be looked down upon as lower class by the commercial immigrants themselves, though less so by Southeast Asians.

Southeast Asian women were therefore the pioneers of cultural interaction with outsiders, a creative role honored by neither nationalist nor imperialist authors. The first areas in which they showed their adaptive skills were naturally in language and in trade, both crucial to the sexual exchange system. As actors in the local marketing system, the women of the commercial centers could advise their foreign partners of market conditions, and act for them when they were away.

If their husbands have any goods to sell, they set up a shop and sell them by retail, to a much better account than they could be sold for by wholesale, and some of them carry a cargo of goods to the inland towns, and barter for goods proper for the foreign markets that their husbands are bound to … but if the husband goes astray, she’ll be apt to give him a gentle dose, to send him into the other world a sacrifice to her resentment” (Hamilton 1727/1930, 28).

Particularly in the early stages, we can assume that it was women who explained to visiting Chinese, Europeans, or Arabs how the system of weights, measures, and currencies worked, and how to develop hybrid ways of doing business between different systems. Money-changers were usually women as long as this profession was dominated by locals.

In the formation of permanently creolized cultures (peranakan or mestizo) of locally born “Chinese” in cities such as Melaka, Manila, and Batavia, the Southeast Asian mothers of the first generations were crucial. Chinese in Melaka and Manila appear to have found their partners among locals, while in more isolated Batavia, slave or ex-slave women provided most of the early partners. The small exiled Japanese Christian community disappeared by assimilation within a century, their daughters largely marrying Europeans, and their sons Christianized Indonesian ex-slaves. Chinese who settled in seventeenth-century Batavia were likely to marry women from Bali or Borneo (who could share their taste for pork). Some of the sons of the most successful might be sent to China for education, but the daughters never were, and the latter tended over time to be the preferred marriage partners of the more established Chinese, thus re-establishing the endogamy of the hybridized group. In 1648 the Captain of the Batavia Chinese died and his Balinese-born wife took over his duties, despite protests from Chinese men. Unlike those of Manila, Christian Chinese in Batavia were rare and little encouraged even among hybrid peranakan. It was the ancestral cults and cycle of temple festivals that held the Chinese community in the Indies together.

The tightly organized European ventures into the Indian Ocean in their initial military stage allowed fewer opportunities to profit from Southeast Asian female partners. Individuals escaping from official control certainly did so, however, to their great advantage in adapting to Southeast Asia. The very first Portuguese expedition to Southeast Asia, that of Diogo Lopes de Sequeira in 1509, believed it owed its survival to a woman from the large Javanese community of Melaka, “the lover of one of our mariners, who came by night swimming to his ship” and warned the Portuguese of the Bendahara’s plans to seize them at a banquet (Albuquerque 1557/1880, 73–4). After his 1511 conquest of Melaka, Afonso de Albuquerque sent three ships to the east to discover the sources of nutmeg and cloves. Its most successful member was its deputy commander, Francisco Serrão, who had the good sense to marry a local woman while provisioning in the Java port of Gresik. Although his ship was wrecked in Maluku, he and his wife, with a few mixed followers, managed to win the friendship of the Sultan of Ternate and lay a basis for Portugal’s intimate relations with the sultanate, which endured until the religious polarization of the 1560s. Virtually all Portuguese in outposts such as those in Maluku, and on the Mainland, had local wives or concubines who played a crucial mediating role as the Portuguese gradually adapted to Asian commercial methods. Among the better-known progeny of these unions were the three sons (as well as one well-married daughter) of Juão de Erédia, who in 1545 sailed away with his Bugis princess rather than confront her reluctant father, the raja of Suppa in south Sulawesi. The couple became pillars of Melaka society. Two sons were leading priests in the city, while the third, Manuel Godinho de Erédia, became a great chronicler and discoverer with a claim to have been the first to map the southern continent of Australia.

The female pioneers in the understanding of Europeans, as in understanding the Chinese before them, naturally became also interpreters and negotiators. Indeed, there is evidence from the Archipelago of their use as negotiators even when language facility was not the issue, presumably because women were accustomed to bargaining and compromise by their commercial roles, where aristocratic men were constrained by fear of compromising status. The first Dutch mission to Vietnamese-speaking Cochin-China found itself dealing extensively with women. The interpreters for the royal court were two elderly women who had formerly lived in Macao as the wives of Portuguese. The Dutch bought their pepper chiefly from another woman who had traveled down from the trade center to meet them.

In Ayutthaya (the Siam capital) the VOC owed much of its success in obtaining advantageous trading conditions in the 1640s to an enterprising woman known to them as Osoet Pegu. Though born into the Mon trading community of the capital, she learned Dutch as a child from frequenting the Dutch traders there. As an adult she became the indispensable link between the Dutch and the court and was taken on as “wife” (in the local rather than Dutch sense) by three successive Dutch agents. Until her death in 1658 she remained a wealthy trader and intermediary with great influence with the Thai queen and key officials. Arguing with her most senior ex-husband, Jeremias van Vliet, for control of their children, she was able to make her case in Batavia by sending an elephant as a gift to the Governor-General. Few subsequent Dutch agents obtained Siamese royal permission to remove their offspring, so that there were in 1689 seventeen Dutch-Siamese children being partly supported by the Dutch post there.

Such key marriage alliances were part of the stuff of Southeast Asian diplomacy, and could extend to the royal courts themselves, which might give and receive daughters in marriage as a means to cement alliances with powerful foreigners. Chinese, Arab, and Indian traders had long understood these relationships and used them to create local cultural hybridities, as did Europeans away from their controlling group. The powerful Sultan Iskandar Muda of Aceh tried to cement his relations with Siam by acquiring a Thai princess as a wife, and also proposed to the English agent Thomas Best that the Company should send English women to him.

If I beget one of them with child, and it prove a son, I will make him king of Priaman, Passaman and of the coast from whence you fetch your pepper, so that you shall not need to come any more to me, but to your own English king for these commodities (Best, cited Reid 1993, 239–40).

This pattern gradually broke down in dealing with Europeans. Christian insistence on lifetime monogamous commitment, along with the group solidarity of often beleaguered company outposts and increasing racial prejudice, handicapped Europeans in making use of this channel. By the late eighteenth century marriage with even high-born Asians was disapproved by colonial society.

What did keep the European presence viable in cities like Batavia was concubinage for ordinary Dutch soldiers and traders, and marriage within the Christian Eurasian community for the elite. The hundreds of thousands of Europe-born men who came to Asia suffered a mortality rate about four times that of those who stayed at home, dying from malaria, smallpox, and various water-borne diseases that proliferated in the dense urban settlements they built. Mortality for Europeans was typically above 10% a year in Dutch Southeast Asian settlements, but rose to a staggering 36% once malaria became endemic in Batavia in 1733. Mortality among the local-born was primarily in childhood, so that the women available for marriage to immigrant Europeans had some immunity as adults, and often outlived several husbands. The Eurasian women also imbibed some healthy habits from their mothers, such as bathing daily and chewing betel (which provided protection against parasites and digestive ailments), and from Chinese acquaintances by drinking their water boiled in the form of tea. In the early phase of Portuguese and Dutch settlements Asian women could rise spectacularly from slave or illegitimate origins to immensely wealthy widows. By the second and third generations more care was taken to keep large fortunes within the elite of Batavia and other settlements. Ambitious men then gained fortunes by marrying the Eurasian widows of well-placed VOC men. A restricted group of well-married Eurasian women became central in controlling the fortunes of Batavia. Their ethnic origins were extremely diverse, their common languages Portuguese and Malay rather than Dutch, but their most important common ritual was weekly attendance at the Protestant church to which they processed in splendor, a slave in attendance carrying a parasol.

Among the most vital mediating roles of Southeast Asian women in relation to the broader evolution of renaissance knowledge were those in botany and human health. Women had always been in charge of child birthing and abortion practices, and the collecting, exchanging, and application of medicinal plants. They astonished early European observers with the abundance of medicinal herbs they sold in the market. They were also prominent as masseurs, bone-setters, and mediums with spirits held to be the cause of mental and nervous disorders. In marked contrast to the European surgeons sent out on Company ships, they knew from long experience how to survive in the tropics. They taught reluctant European men to wash daily as the price of access to sex. When European writers condescended to acknowledge the source of their remedies it was usually from female herbalists. The pioneer of tropical medicine Jacobus Bontius (Jacob de Bondt, 1591–1631) reported that “every Malayan woman is her own physician and an able obstetrician and (this is my firm conviction) I should prefer her skill above that of a learned doctor or arrogant surgeon” (cited Sargent 2013, 149). In India and China the comparable European pioneers had little contact with women and were led into theoretical discussions with male Ayurvedic and humoral specialists, whose theories were of little practical help. Medical theory in Southeast Asia had not been formalized into any such male-dominated intellectual system with more prestige than effectiveness. At a practical level, Southeast Asian medicine depended much on herbal antiseptics and cures, where “their botanic knowledge … is far more advanced than our own” (Bontius, cited Sargent 2013, 148). This knowledge was most explicitly formalized by Rumphius (Georg Eberhard Rumpf, 1627–1702), the great savant of Ambon, whose exploration of Southeast Asian herbs aided the development of scientific botany in Europe. Like Bontius, he had a high opinion of his female informants, but especially of his Malukan wife tragically killed in the great tsunami of 1674, whose vital role in his knowledge of medicinal plants he graciously acknowledged.

Cultural Hybridities

The Portuguese language, with its various creole variants, became one of the key mediators between East and West in the trading cities of Asia, important even in seventeenth-century Dutch Batavia where Portuguese power and Catholic worship were forbidden. Its interaction with the Malay lingua franca provided the field for cultural transfer and interaction in the creative cities of the sixteenth century. Arabic vocabulary had begun entering earlier, and Hokkien Chinese and Dutch were added to the mix in the seventeenth century. Thus while most of the days of the week were taken from Arabic, Sunday (minggu, also the word for week itself) is from Portuguese. The Dutch pastor and writer Francois Valentijn was among the first to point out the difference between the written high Malay of Muslim texts and palace diplomacy, “which is not understood even on the Malay coast … apart from Muslim kings, rulers and priests” and the low or hybrid Malay, bahasa kacukan, which “is derived from many nations … sometimes mixed with some words from Portuguese, or from any other language” (trans. Maier 2004, 9).

Female dress was one of the items most rapidly changed by the foreign male gaze, whether Arab, Chinese, or European. Cloth and clothing, especially the colorful styles imported from India, were the most conspicuous items of extravagance in Southeast Asia, perhaps because the low-born were not inhibited by sumptuary laws from exhibiting their wealth this way. So although Europeans and Chinese were surprised at what they considered indecently light clothing, with usually bare feet and heads, and with little more than a scarf above the waist, the extravagance of adornments was equally surprising. Even into the nineteenth century, Javanese, Balinese, Thais, and Bugis considered a bare upper body carefully prepared with oils, perfumes, cosmetics, and jewelry the most appropriate dress for both sexes on high ritual occasions. Yet in protecting the genitals from view, Southeast Asians were more fastidious than most of the visitors, obliging French soldiers, for example, to wear a sarung when bathing in the river of Siam.

A major effect of the commercial boom was the expansion of imported cloth from India, and experimentation with finery from all quarters of the world. Traders were pressed to provide rare and exotic items, particularly opulent clothing or ornaments for the bodies of the wealthy. Since sewn and fitted clothing had been rare until this revolution, European or Middle Eastern jackets and Indian trousers were in demand as novelties. The Makassar rulers greeted visitors in the seventeenth century with European cloth coats over their otherwise bare upper torso. Gradually, however, sewn upper garments more appropriate to the climate were devised and requested from India or sewn locally. The very different ideas of female propriety of Muslim, Christian, and Chinese males became influential selectively, beginning in the commercial cities where such men were concentrated. In Portuguese Melaka the local partners of Portuguese men, even when Christianized and attending church, continued to wear flimsy upper garments and bare heads until the Jesuits arrived and forced them into more Portuguese-style dress in the mid-sixteenth century. In the Philippines also, Christian converts were pressured to adopt a Spanish style of dress, fully covering the female body. But the most influential innovations were the hybrid styles which maintained the wrap-around cloth for the lower body (Malay sarung), but added first a breast-cloth, somewhat less revealing than the scarf, and eventually a sewn blouse or tunic. In the Malay-speaking world of Southeast Asia’s port-cities, many of the words for sewn garments were of foreign origin – kemeja (shirt), celana (trousers), and sepatu (shoes) from Portuguese, and later jas (jacket) and rok (skirt) from Dutch. The urban women who interacted with foreigners in the ports developed a Portuguese-influenced distinctive upper garment, the kebaya (though the word may be derived from Arabic), often so fine as to be transparent, making the sarung-kebaya combination the hybrid female dress par excellence of the region.

Performance had long been the cultural form of choice in Southeast Asia. Localized Indian stories of the Mahabharata and Ramayana, alongside some local traditions, were learned and loved not through reading but by experiencing as dance and theater. In the stateless societies held together largely through ritual and religious ceremony, feasting was always accompanied by music and dance, intended to link the living with the spirit world as well as to entertain and provide opportunities for matchmaking. Weddings, religious occasions, and funerals were all enlivened by music and dance, while the river-boatmen sang to keep time as they rowed. Where royal courts arose, they demonstrated their eminence as cultural exemplars. There, performance reflected both their religious centrality and their cosmopolitanism. Foreign visitors were sometimes entranced by this activity, but often complained that they had time for little else than to witness dances and dramas lasting through the night.

In this regard, too, the age of commerce was a period of great innovation and borrowing. The port-capitals that became great centers of cultural exchange rejoiced in their eclecticism. Stringed instruments were introduced from the Middle East, China, and Europe to expand the ancient Southeast Asian mix of bronze percussion instruments and flutes. Each foreign community was expected to provide its style of entertainment for court and public occasions. A Malay text from Sumbawa, too far east for the major commercial encounters, nevertheless showed its cosmopolitanism by listing “all kinds of entertainments like Indian dances, Siamese theatre, Chinese opera, Javanese puppet theatre and music of the viol, lute, kettledrum, flute, bamboo pipe, flageolet, kufak and castanets” (Hikayat Dewa Mandu, 257). Most of the “traditional” theatrical forms were created in this period out of the encounter of older patterns and the new religious and social norms. The shadow theater (wayang kulit) of Java certainly had older origins in religious ritual, but both it and the masked drama (wayang topeng) assumed their familiar modern form in the cosmopolitan ports of north Java during the sixteenth century, presumably as a way of telling the popular Indian stories in oblique ways not explicitly confronting Islam. The shadow theater spread to the Mainland, but was there confined to a more esoteric ritual role, while Thai masked drama (khon) developed for the beloved Jataka stories about the life of the Buddha, and Java-derived unmasked dance drama (lakhon) for the highly popular stories of both Indian and local origin. The Vietnamese national dance drama (hat boi) was also developed and popularized around 1600 by the addition in the south of Cham and other themes to the older Chinese-inspired northern opera.

Clifford Geertz (1980, 123–5) aptly remarked that Southeast Asian rulers were engaged in a “continual explosion of competitive display” to demonstrate their exemplary status through public theater and ritual. Whatever power each state possessed derived from “its imaginative energies, its semiotic capacity to make inequality enchant.” In the port-states that set the cultural tone in the long sixteenth century, the foreign traders were essential to the demonstration of royal success and status. The English factor in Banten, Java’s preeminent such state of the time, described the challenge of doing at least as good a job as the Dutch in making a spectacular display to honor the circumcision ceremonies of the boy-king, which dominated the city throughout the trading season from March to July 1605. The Europeans had little chance to impress in comparison with Chinese opera, fireworks, and acrobatics, and all manner of Javanese processions with hundreds of splendidly adorned women and men, pageants, and floats, including mock forts and battles, ships laden with gifts, dragons and

“many sorts of beasts and fowls, both living and also so artificially made that … they were not to be discerned from those that were alive”, theatre and dance, all kinds of music, and “significations of historical matters of former times, both of the Old Testament and of chronicle matters of the country and kings of Java. All these inventions the Javans have been taught in former times by the Chinese; … and some they have learned by Gujaratis, Turks and other nations which come hither to trade” (Scott 1606/1943, 154–6).

The first generation of rough European trader-soldiers had little to contribute to the mix, though any ship that did carry musicians, like Francis Drake’s in Ternate and Java in 1579–80, found them in great demand to join the competitive performance of the ports. In the longer term the European contribution to Southeast Asian music was considerable. Catholic Church music was one of the great attractions of that new faith in the island world in general, and Filipinos became extremely proficient in Gregorian chanting and instrumental music. They and the Portuguese-influenced communities of Melaka were in demand as performers throughout the region, and spread European instruments and themes everywhere. Dutch and English Protestants placed less emphasis on music, but found in the singing of the psalms of David, as the first English voyage was requested to do in Aceh, a point of intercultural contact with Muslims. In Dutch Batavia the great households had their slave orchestras, whose descendants spread the knowledge of instruments and melodies much further afield. The violin was so valued for its virtuosity that it had spread widely by the eighteenth century. Thomas Forrest (1729–1802), an unusually cultivated country trader, regularly ingratiated himself with the local elite where he traded by exchanging performances with them and presenting key allies with violins. Muslim Magindanao was outside the bounds of Spanish control or Christian influence, but in 1776 he found the heir apparent to its throne (raja muda) was a violinist who showed great interest in Forrest’s demonstration of musical notation.

Rumphius was a rare case of acknowledging the role of his local wife in his discoveries, but we must assume that many of the important “European” accomplishments of the period were born from intense interaction with a well-informed local woman. One such was the Mon-Siamese Osoet Pegu, mentioned above. The father of her three daughters, the VOC’s Jeremias van Vliet, was also the best-informed foreigner of his day on Siamese history and culture, and his three precious works on the subject could not have been written without her.

Islam’s “Age of Discovery”

Muslim voyaging in the fifteenth century was no state enterprise but the business of individual entrepreneurs of many different ethnicities and cultures, communicating with each other through the religious and legal commonalities of Islam. As maritime peoples in southern Asia were drawn into cosmopolitan relations through the boom of the long sixteenth century, many saw in Islam a new universal. It asserted strongly that there was only one God for the whole planet, one true path, and one revelation in a particular language – Arabic. Even more than Pollock’s “Sanskrit cosmopolis” of the first millennium, the “Arabic cosmopolis” of the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries created a global imperative above place and culture. With it came a network of scholars and manuscripts, as well as story-tellers and their tales, translating the idioms of Arabic and Persian into Malay and Javanese. Malay was transformed in the process, adopting a modified Arabic script and a host of terms from the Arabic and Persian. Whereas the older Indic-derived manuscripts had been written on palm-leaf, paper was more appropriate to the swirls and dots of the Arabic script. Large quantities of it were imported to Southeast Asia, mainly from China in the fifteenth century but Europe by the seventeenth. Yet it was Arabic words for paper, pen, and ink that were adopted by Malay, and in the case of paper even into Thai.

This Indian Ocean world was the largest venue of Eurasian exchange in the fifteenth century, but European knowledge was peripheral to it. That changed when the Ottomans conquered Constantinople with its legacy of Greek learning in 1453. Their extraordinary expansion continued to the key portages of Eurasia’s maritime routes – the rich prize of Egypt in 1517, and the keys to the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea in 1537. The Ottomans became a bridge more effective than the Portuguese between the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean worlds. Their “Age of Discovery” was able to combine European and Arab knowledge of maritime discoveries. In 1516, Ali Akbar’s “Book of Cathay” (Hitayname) was presented to Sultan Selim, with a first-hand account of a trading voyage to China more informative than any European account of the time. Not long after Selim took control of Cairo in 1517 he was presented with the even more remarkable world map of Piri Reis, intended to inform the sultan about the potential of the Indian Ocean and its spices, to which Turkey now had easier access than the rival Europeans.

How technical advances were exchanged in the East is not always clear. Muslim traders in the Indian Ocean certainly made use of charts before the encounter with Europeans, and some of them must have learned very quickly of the Portuguese discoveries in the Atlantic. When Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Melaka from its Muslim Malay dynasty in 1511 he acquired from a Javanese pilot there a map he considered the finest he had ever seen. It showed the Portuguese discoveries including Brazil and Africa, as well as Europe, Muslim routes from the Red Sea to Maluku, and Chinese ones from Fujian and Ryukyu. Unfortunately it was lost with other treasures being sent home to King Manuel in the wreck of the Flor de la Mar.

Despite the Turkish failure to expel the Portuguese from their Indian Ocean strongholds (Chapter 5), they had more direct influence on the peoples of the Indian Ocean littoral than did the Portuguese. The fundamental difference between the two contenders was that the Portuguese fleets represented from the beginning a state-funded and directed monopoly, as outsiders in Asia with few natural allies. The Ottomans were drawn into the Indian Ocean by appeals from the established commercial centers like Gujarat and Aceh for military protection against the Portuguese intrusion. The Ottomans had laid claim to a universal Caliphate in 1518, immediately after conquering Mecca, and this added to Asian hopes for protection. The Islamic cosmopolis peaked in the second half of the sixteenth century at a time when religious polarization highlighted universal norms at the expense of the local. Islamic books, like the parallel Catholic ones in the Philippines, introduced to the southern islands a new pattern of text-based scholarship, using written texts on paper to translate and explicate the sacred canon. Ottoman subjects also transferred navigational, shipping, and military technologies to the Muslim ports.

Southeast Asians had long been literate, but popular piety had primarily been expressed visually in the form of statuary and theatrical performance. The Islamic cosmopolis brought a new emphasis on the written word and its texts, debates, and erudition. From the 1560s Aceh became the Southeast Asian hub of this cosmopolis, welcoming learned ulama from South and West Asia and producing a number of its own. The tradition of scholarly writing in the Malay language was effectively created in Aceh during this key century, with important offshoots in cosmopolitan ports like Banten, Makassar, Demak, and Patani. While the great majority of surviving translations and commentaries were in the Islamic scholarly tradition, the works of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries were consciously innovating in their attempts to reconcile scriptural norms with the inner-directed mystical and ascetic traditions of earlier periods. A few texts on technical and scientific matters have also survived, and the transfer of Turkish military and naval technology to centers such as Aceh, Johor, and Makassar was extensive.

The European contribution to this cosmopolitan moment was not limited to military technology, although that was the first to make an impression. By the seventeenth century the Jesuits were representing the best of European mathematics and astronomy to Asia. Alexandre de Rhodes was the best known (thanks to his writings) of their scholar-missionaries in Southeast Asia, and described his discussions with the elites in Makassar (see below) and Tongking. He gained access to the northern Viet court by presenting the king with a Jesuit rendering into Chinese characters of how Euclid’s sphere worked, which so interested the ruler Trinh Trang (1623–52) that he talked mathematics and astronomy for two hours with the Jesuit and gave him permission to stay and build a church. The Jesuits in Cambodia found themselves in competition with knowledgeable Chinese, and urged their peers to make sure they made no mistakes in predicting lunar eclipses so as not to be ridiculed. The Dutch were also competitors in science, presenting or trading telescopes and clocks to the leading trade centers – even as far as the Lao capital of Vientiane.

European paper was becoming popular by 1600, replacing the palm-leaf of the older era to make possible the explosion of new writing on Islamic subjects especially. But printing was not so quickly taken up. Printing presses were introduced by the Spanish to the Philippines in 1593, followed by the Dutch in the Archipelago and French missionaries in the two Viet states. In each case European missionaries printed texts in a roman alphabet they devised to replace older alphabets for Tagalog, Malay, and Vietnamese, respectively. In the long run each of these printed roman alphabets was hugely influential, becoming the national languages of great modern countries and opening the door to the eventual rise of a European cosmopolis. At the time, however, the printing presses sparked surprisingly little interest except in Christianized circles. The explanation must be sought in the broader distrust of missionary printing presses for reproducing the sacred texts of Islam and Buddhism, a distrust that would endure until the twentieth century.

Southeast Asian Enlightenments – Makassar and Ayutthaya

The Asian-ruled cities most visited by curious Europeans were the best documented examples of how cosmopolis worked. Makassar was the leading port in eastern Indonesia from about 1580 to its capture by the Dutch in 1666. Before its rise, the Makassarese corner of Southwest Sulawesi was as politically fragmented as the Bugis societies to its north. Both were primarily rice-growing agricultural peoples, governed by a proud heaven-descended aristocracy whose relations with one another were governed by contracts supernaturally sanctioned by oaths. Writing in an Indic-derived script appeared to have been introduced only in the fifteenth century, and was largely used to record genealogies. Malay/Muslim traders began visiting the area in large numbers in the 1540s, and were persuaded to make their base near modern Makassar in mid-century. The reason may have been in part Portuguese attempts to convert rulers in their earlier settlements further north, but also the skill of the Makassar kings in guaranteeing key autonomies to the Muslim trading community.

Politically Makassar flourished as a partnership between Gowa, on the larger Jeneberang River that provided the sovereign, and Tallo’, a more maritime center to its north that provided the Chancellor of the kingdom and managed its trade. It was two Tallo’ figures in particular who guided Makassar as Chancellor through its most successful period: Karaeng Matoaya in 1593–1637, and his son Karaeng Pattinggalloang in 1639–54. Matoaya led Makassar into Islam in 1605, at a time when both Sunni Islam and Catholic Christianity were well known, while the Protestant Dutch and English had begun to make their presence felt as opponents of Portuguese Catholics. Islam was the means by which Makassar established its primacy over all the Bugis and Makassarese polities of south Sulawesi, but both Makassar and Bugis chronicles show Matoaya explicitly recognizing their traditional autonomies. Although the dress code and manners of the Makassarese were changed by Islam, they remained no less open to the Europeans. Matoaya was reported to be very dutiful with his five daily prayers after his conversion, and only had to miss them when he went to an Englishman to cure his swollen foot, who treated him with alcohol. Another Englishman reported in 1612 that “It is a very pleasant and fruitful countrye, and the kindest people in all the Indias towards strangers … The King is very affable and true harted towards Christians” (cited Reid 1999, 144). Indeed one of the sultan’s wives was Portuguese, and the son of this union, Francisco Mendes, became an indispensable, trilingual “Portuguese secretary” to the court in the 1640s. At that time Muslim Makassar had four Catholic churches to cater for Jesuits, Franciscans, Dominicans, and the secular clergy expelled from Melaka (Figure 6.1).

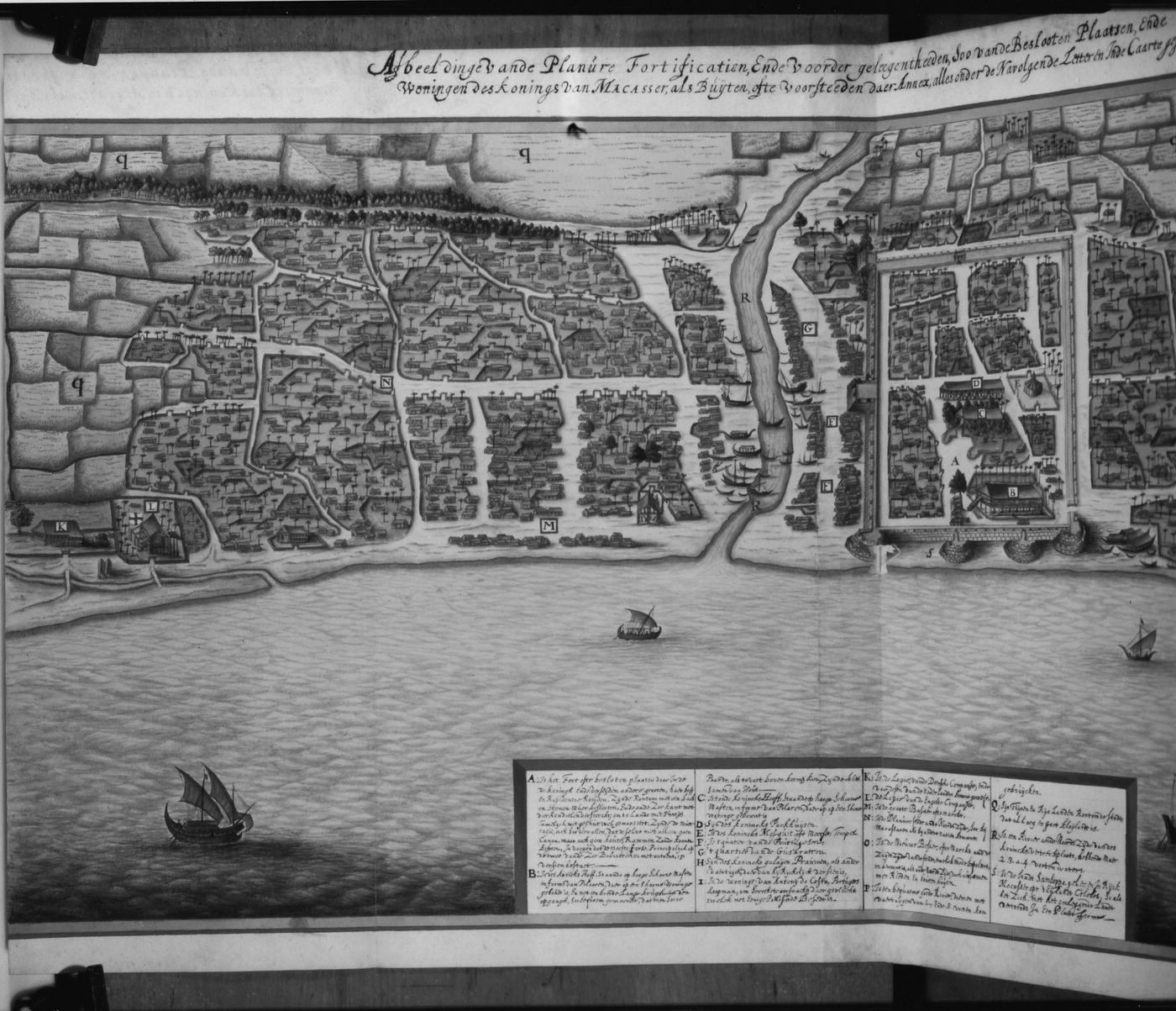

Figure 6.1 Makassar in 1638, as drawn by van der Hem for the “Secret Atlas of the VOC.” The citadel at right contains: the Sultan’s palace (B) on wooden pillars, the former palace (C), royal warehouses (D), and royal mosque (E). The channel to its left was newly dug as an outlet to the Jeneberang River, with Portuguese (F) and Gujarati (G) quarters beside it. To left of the channel are the Portuguese church, Market (M), English (L) and Dutch (K) lodges.

Source: Anthony Reid, “Southeast Asian Cities before Colonialism,” Hemisphere 28:3 (1983), 144–5.

Makassar’s prosperity depended on being a spice port open to all comers, at a time when the VOC was using every means to assert a monopoly over both clove and nutmeg. All other traders found Makassar the safest place to buy their spices, as long as small boats could evade Dutch blockades to get the spices to Makassar, and the city itself was strong enough to deter a Dutch conquest. Some hundreds of Portuguese were based there in the 1620s, and several thousand after the Dutch took their major base of Melaka in 1641. To the VOC’s demands for monopoly Makassar insisted on even-handed freedom for all. “God made the land and the sea; the land he divided among men and the sea he gave in common. It has never been heard that anyone should be forbidden to sail the seas” (Sultan Ala’ud-din 1615, cited Stapel 1922, 14). But Makassar’s position was only viable if it was strong, and the elite were intensely interested to learn key military techniques from Portuguese, English, or Muslims. The Makassar chronicle, which reads as a litany of innovations, declares that Karaeng Matoaya was the first to introduce the manufacture of cannons and muskets, and was himself “skilled at making gunpowder, fireworks, flares, and fireworks that burn in the water, as well as being an accurate marksman” (cited Reid 1999, 138).

Karaeng Pattinggalloang, who succeeded his father as Chancellor of the joint kingdom, was an even more remarkable “renaissance man.” He had all of his father’s intellectual curiosity, but the added advantage of a cosmopolitan upbringing that gave him fluency in Portuguese as well as Makassarese and Malay, and at least a reading knowledge of Spanish and Latin. He pestered visiting European ships for novelties, but particularly for books of which he built up a considerable library. The fullest first-hand account we have of him is that of the French Jesuit scholar Alexandre de Rhodes, who wrote of his time in Makassar in 1646:

The high governor of the whole kingdom … I found exceedingly wise and sensible, and apart from his bad religion [ie Islam], a very honest man. He knew all our mysteries very well, had read with curiosity all the chronicles of our European kings. He always had books of ours in hand, especially those treating of mathematics, in which he was quite well versed. Indeed he had such a passion for this science that he worked at it day … and night. To hear him speak without seeing him one would take him for a native Portuguese, for he spoke the language as fluently as people from Lisbon itself.

Seeing that he was pleased to talk of mathematics, I began conversing with him on the subject, and God willed him to take such pleasure in it that he wanted to have me at his palace as a matter of course thereafter. It happened that I predicted an eclipse of the moon to him a few days before it took place … This so won him over he wanted me to teach him all the secrets of this science (de Rhodes 1653/1966, 208–9).

Although the Dutch were the chief threat to his kingdom, they acknowledged Pattinggalloang’s remarkable scientific mind and did their best to supply his demands for the latest world maps and globes. A telescope of the latest Galilean kind had also been requested from the English in 1635 in the name of the sultan, but this sadly arrived only years later when the Chancellor was dead and this enlightenment moment gone with him.

Although this remarkable Chancellor was only one unusual man, there were wider indications of a court culture of curious cosmopolitanism. Makassar offers the best evidence we have for the translation on Southeast Asian auspices not only of religious texts but also of European and Turkish technical manuals. Surviving manuscripts in both Makassarese and the quite different (but generally better preserved) Bugis language provide translations and summaries of works on gunnery, gunpowder, and ballistics by Spanish, Portuguese, Turkish, and Malay authorities. The practical consequences of this were seen after Pattinggalloang’s death, when twelve large iron cannons of over a tonne weight, 34 smaller bronze cannons, and 224 culverins defended Makassar against a massive Dutch assault in 1669. Pattinggalloang’s interest in maps appears also to have stimulated an unusual south Sulawesi tradition of map production.

The influence of Arabic and Persian models of history-writing, verse-epics, and literature spread through Islamic trading networks in this innovative Early Modern period. Chinese example was strongest through the spectacle of Chinese (usually in fact Hokkien) Opera, staged at festivals wherever there was a substantial Chinese trading community – certainly in Banten, Patani, and Hoi An by 1600. European models were more important in Makassar, where a habit began in Pattinggalloang’s time of carefully recording important events in a state diary. Each day’s date was given in both Muslim and Christian form. A genre of historical chronicle unusually matter-of-fact by Southeast Asian standards also developed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The Goa (Makassar) chronicle began with an explanation of why it was important that future generations remember the past, “to avoid the twin dangers, either of our thinking that we were all great kings, or of others alleging that we were worthless” (Sejarah Goa).

The placing of a high value on personal freedom is often thought a key feature of the European Enlightenment, and, ever since Herodotus, has been stereotyped as alien to Asia. It is therefore significant that south Sulawesi society, following this enlightenment moment, appears to have been one that particularly prized its freedom. The rise of the gunpowder empire of Makassar was carefully balanced by traditional south Sulawesi contractualism, expressed in the idiom of freedom (merdeka) as the opposite of slavery. At least in the Bugis kingdom of Wajo’, rituals of inaugurating a new king required him to guarantee the personal freedoms of speech, property, and movement of his people – by which was meant, as in ancient Greece and Jeffersonian America, his free people, not their slaves.

The Siamese capital of Ayutthaya during the remarkable reign of King Narai (r.1656–1688) is the second example, alongside Makassar, about which there is enough information to be able to show the effects of cultural exchange at this exceptional moment. The cosmopolitan capital attracted “a great multitude of strangers of different nations, who settled there with the liberty of living according to their customs, and of publicly exercising their several ways of worship” (La Loubère 1691/1969, 112). La Loubère estimated about 3,000 each for the number of Indian Muslims, Portuguese, Malay Muslims, and Chinese, with influential pockets also of Dutch and French (the two who left the best records), English, Japanese Christian refugees, and Mon Buddhists. The king was a cosmopolitan modernizer, though a ruthless autocrat internally, and surrounded himself with educated people, including even the multilingual Greek adventurer Constance Phaulkon, who served him as effective minister for foreign relations in the 1680s.

The scientific curiosity of King Narai was first served by the VOC, to which he had granted extraterritorial rights in 1664, ending a period of mutual suspicion. Thereafter the Company was the most consistent provider of European expertise, sending him not only military assistance with artillerymen and gunpowder manufacturers, but also clocks, telescopes, a glassblower, goldsmiths, sculptors, and medical men. The French sought to top this with an elaborate royal mission in 1685, accompanied by six of the most learned Jesuits in France. They arranged to be in Siam for a total eclipse of the moon on December 10, 1685, with the double purpose of impressing the king and calculating more accurately the meridians of Paris and Siam. The Jesuits reported how curious the court circle was to exploit these scientists, frequently sending their own scholars to pose questions about the nature of the sun, the winds, and so forth. The king requested that a larger team of Jesuit “mathematicians” be sent out to Siam, and agreed to build for them a handsome observatory, never realized because of his overthrow and death in 1688. In literature, too, Narai’s reign demonstrated remarkable innovation, with the first truly secular histories and poetry.

Gunpowder Kings as an Early Modern Form

One is struck in reading the accounts of seventeenth-century travelers in Southeast Asia how well they understood the basic form of polity they encountered. They seemed to be dealing with courts and cities familiar enough to appreciate, in contrast with their nineteenth-century counterparts who saw at best eccentric exoticism, at worst decay, self-indulgence, and incompetence. Early Modern kings in many parts of the world were aware of their interdependence as well as competition, and understood that they surmounted fragile pinnacles of power that needed to be demonstrated and legitimated theatrically. Presiding over rapidly urbanized port-capitals, they impressed with extravagant forms of state theater, even more than by ambitious building projects and the accumulation of weapons. They exchanged envoys to impress and manipulate each other, but also to discover how the game was played elsewhere.

At both ends of Eurasia, elites were impressed with new discoveries, marvels, and curiosities from afar. European rulers assembled them in curiosity cabinets or wunderkammer to demonstrate not the vastness of their empires (as in the nineteenth century), but their cosmopolitan sophistication as people who understood the new world. No less in Southeast Asia did the elite display their status in this period by the possession of rarities. The age of commerce was made possible by the enthusiasm of Southeast Asians everywhere for colorful India-produced cloth, readily selling their spices and tropical exports in return for these imports. Nothing better defines the end of this period in the seventeenth century (Chapter 7) than the turn against foreign cloth and exotic fashions.

The rulers of the age of commerce eagerly questioned arrivals from afar, anxious both to measure themselves against their global peers, and to use distant connections for their own purposes. A feature of gunpowder kings everywhere was their dependence on foreign traders, financiers, and mercenaries. Envoys who brought an authentic letter from their monarch were received with great ceremony at the courts of Southeast Asia, the letter being carried in procession by caparisoned elephant ashore or gilded galley on the river. One of the last such exhibitions of royal theater, the reception of a French mission to Siam in 1687, assembled about 3,000 men in 70 decorated galleys, with musicians and dancers, to accompany the Ambassador up the river. The addition of European envoys to the Asian diplomatic mix led to embassies in response. Aceh in 1601–3 and Siam in 1607–8 sent envoys to Prince Maurits in Holland, but after beginning its career of conquest in 1619, the VOC refused to allow future envoys further than Batavia. Later embassies were therefore sent in hope of help against the Dutch. Banten sent one celebrated embassy to Charles II in England (1682), and Siam a series of embassies to Louis XIV in response to French initiatives, in 1680, 1684, and 1686–7. The fall in Asia of the monarchs who sent them, and a loss of interest in Europe, ended this phase of curious exchange.

The theater of state reached a peak during the long sixteenth century in the form of elaborate processions to honor the accession or death of the king, or of some wedding or religious festival over which he presided. At the same time as Europe developed the royal parade into an allegory of state power at such grand moments as the entry of Charles V into Rome (1530), Henry IV into Paris (1628), or Elizabeth (1588) or James I (1604) into London, Southeast Asia’s gunpowder kings also altered the great public rituals from religious themes to those essentially celebrating themselves. The “theater state” concept was developed by Clifford Geertz (1980) to explain nineteenth-century Bali politics, but it applies even better to the gunpowder kings of the age of commerce. In Aceh the processions awed the watching crowds with the abundance of richly adorned elephants (260 at the last such grand occasion, in 1641), exotic creatures like rhinoceros and Persian horses, and thousands of armed men. In the Mainland river-capitals and those of Borneo, the greatest such processions were of galleys on the river. As a Dutch resident described an annual ritual in Siam,

In front go about 200 mandarins, every one with his own beautiful boat and sitting in a small pavilion which is gilded and decorated according to the rank of the owner. These boats are rowed by 30 to 60 rowers … In the finest boat the king is seated under a decorated canopy … surrounded by nobles and courtiers who pay him homage at the foot of his seat … The total number of boats amounts to 350 to 400, and 20,000 to 25,000 persons take part in the procession (van Vliet 1640/2005, 119).

In the later seventeenth century such grand occasions declined quickly, in Asia as in Europe, as monarchs no longer controlled the resources for them, new firearms made rulers dangerously vulnerable in them, and royal theatrical energies were redirected to more elegant and introverted occasions within the palace walls.

These parallels are more than coincidence, but reflect a certain ecumene, in which kings in different corners of Eurasia saw themselves as competitors within a moral order to some extent common. There was more contact and knowledge than in earlier periods, more mutual respect and curiosity than in later ones. One reflection of the time was the popularity of the literary genre known as “Mirrors of Princes,” or Mirat al-Muluk in Arabic, mediated to Asia largely in its Islamic form. Familiar in both Christian and Islamic worlds from the eleventh century, this genre became both more popular and more widespread in the long sixteenth century when gunpowder kings needed guidance in how to surmount the unsteady pinnacles of power to which they had been projected. An explicit borrowing from Persian and Arabic sources into Malay was the Taj as-Salatin (Crown of Sultans) dedicated to the Aceh sultan by Bukhari al-Jauhari in 1603. This in turn was emulated in other Malay texts like Raniri’s Bustan as-Salatin (Garden of Sultans, 1643), translated into Javanese and widely cited in the following period. Like much of the best of the genre in the same period in Europe and the Middle East, it condemns tyranny with colorful examples, and extolls the centrality of reason for a good king. Reason was the first thing God created, the essential virtue for guiding the conduct of king and commoner.

Reason in the human body resembles the sun in the sky, of which the rays illuminate every corner of the world. … Everything, good or evil, is apparent to those endowed with reason, just like colours, white or black, are clearly discernible in the light of the sun. Therefore you should glorify reason, so that your reign may become perfect (trans. Braginski 2004, 437).

Subsequent events would erect walls between cultures, and dull the interest for learning from one another. Nevertheless, Early Modernity had begun.