[17] The Military, Monarchy, and Marx: The Authoritarian Turn, 1950–1998

The first generation of revolutionary nationalists had more difficulty occupying the legal-bureaucratic space of the colonial states than the charismatic space in people’s hearts. The first symbolic leaders of the upheavals that delivered proudly independent and assertive states – Aung San, Ho Chi Minh, Sihanouk, Sukarno, Phibun Songkhram, Tunku Abdul Rahman – achieved an almost supernatural aura from their identification with racial/national liberation, though some of their henchmen also spilled considerable blood to achieve that result. Their successors invariably imposed more of an iron hand; particularly so in the post-revolutionary regimes that enforced a single definition of the fruits of revolution. The shift to military rule in the 1960s was frequently justified in terms the Japanese military had taught, that liberal democracy was inherently weak, divisive, and unsuited to Asia, and that unity against foreign threats was the supreme goal. Where monarchy made a kind of comeback it was seen sometimes as revalidating endangered identities, sometimes as a gentler means than the military one of maintaining the legitimacy and charisma of the fragile new state. Even as democracy returned after the Cold War, the Thai and Brunei monarchies, and communist parties in Viet Nam and Laos, provided surprisingly enduring bulwarks for those who feared its rise.

Democracy’s Brief Springtime

The young idealists who powered the revolutionary tide of the late 1940s had little doubt that popular sovereignty and democracy were the goal and destiny of the vast new nation-states they sought to create. Fascist ideas of single-party integralism had been popular earlier, but were discredited by the defeat of Japan and the other Axis powers. Even amidst the desperate if euphoric first months when the survival of the newly proclaimed states was in grave doubt, Republican Indonesia, Viet Nam, and Burma held makeshift elections. For all its shortcomings, David Marr (2013, 52) points out that the Vietminh effort “proved to be the fairest election the DRV/SRV has experienced to the present day.”

In post-revolutionary Burma and Indonesia, the extraordinary diversity of armed groups and competing visions – religious, Marxist, ethnic – made democracy both necessary and unworkable. As Hatta pointed out in attempting to deal with the problem, “National Revolution stimulates and embraces elements that cannot distinguish means from ends, reality from an ideal, who believe that every change has to be by revolution” (Hatta 1954 IV, 171). Democracy was seen as the only way to incorporate contradictory visions within a single state, and to establish which had electoral strength. But convincing those with armed followings to wait for and then abide by the results of elections was a tall order. Those who had grasped the executive authority from the departing colonials proved unwilling to surrender it to the ballot box. The Vietminh allowed no challenge to its leadership of the revolution, and even the more plural and parliamentary AFPFL only prevailed in its 1956 election by using the military to engineer the right vote.

Indonesia was the only Southeast Asian country to make a habit of changing governments in response to parliamentary shifts. There the 1950 negotiated constitution had continued the de facto separation of the revolutionary period between the presidency (Sukarno and Hatta) and an executive cabinet responsible to parliament. Prime Ministers and their cabinets changed, if anything too frequently, with ten cabinets under five Prime Ministers of the embattled Republic of 1945–9, and ten more under nine Prime Ministers in the remainder of the parliamentary democracy period to 1959. With Sukarno (Java-Bali), and Hatta (Minangkabau), until his resignation in despair in 1956, remaining as its symbolic embodiments, the nation appeared strengthened rather than disrupted by these changes of cabinet. The first (and last until the new century) fully democratic elections in 1955 drew 39 million enthusiastic Indonesians to the polls, a turnout of 92%. The nationalist party (PNI, 22% of votes) and Islamic reformists (Masjumi, 21%) did well as expected, but socialists and others were destroyed, while votes from the Javanese rural heartland enabled two newcomers to join what became the “big four” parties – the NU traditionalist Muslims (18%) and the communist PKI (16%). It had been hoped that the election would somehow deliver on the high but contradictory expectations that independence had brought. It appeared to do the opposite, increasing the dismay of the political elite at the rise of the non-elite NU and PKI, and the polarization between the increasingly vociferous PKI, indulged by the President, and anti-communist elements such as Masjumi and the military.

The dissident armed groups did not wait to test their strength at elections. Communist and Karen rebels made survival difficult for the AFPFL Burma government, and did not participate in the 1950, 1956, and 1960 elections. In Indonesia the communists after their 1948 disaster took a legal and parliamentary path, but those who believed their revolutionary struggle had been for an Islamic, or a loosely federal, state declined to surrender their arms to a centralized secular order. The Ambonese separatism of the South Maluku Republic was relatively quickly if bloodily suppressed in 1950, but the Islamic rebellions were more tenacious, since militants were already hardened to a guerrilla existence in Dutch-occupied areas. S.M. Kartosuwirjo (1905–62) had established the Darul Islam (DI) guerrilla force in West Java in 1948, and in August 1949 declared a separate Islamic State – Negara Islam Indonesia. In January 1952 this was joined by the charismatic South Sulawesi guerrilla leader Kahar Muzakar (1921–65), and in 1953 by the now-disgruntled leader of Aceh’s exemplary resistance to the Dutch in 1945–9, Mohammad Daud Beureu’eh (1899–1987). The parliamentary governments, fortunate in avoiding Burma’s problem of long land borders to sustain its rebels, countered all these movements comparatively successfully through a mixture of negotiation and brutal repression by its increasingly effective army.

Malaya (1955) and Singapore (1955 and 1959) established through elections under colonial auspices the leadership that would inherit the charisma coming with independence – Kedah prince Tunku Abdul Rahman (1903–90) and Cambridge-trained lawyer Lee Kuan Yew (b.1923), who led Malaya/Malaysia until 1970 and Singapore until 1990, respectively. Neither country has abolished parliament and regular elections since, though ensuring against changes of government through control of the media, juggling the voting system, and either co-opting opponents or crushing them judicially. In the mid-1950s Thailand had a brief experiment with democracy, a freer press, and an election in 1957, though quickly reversed by another military coup. Even in embattled Indochina the 1950s were the time of democratic optimism. The 1954 Geneva agreements specified that the two Vietnamese states (together), Cambodia, and Laos would have elections to determine all the disputed issues. South Viet Nam declined to take part in the joint election, but did hold its own parliamentary election in 1955 without any significant parties being allowed to organize. Laos and Cambodia had already had French-supervised elections in 1946–7 and 1951, delivering support to nationalists pressing for rapid independence and a neutralist line toward Vietnamese communism. In Laos, the neutralist Paris-educated prince Souvanna Phouma (1901–84) was again returned as premier in 1955 having already won the 1951 election. In Cambodia, King Sihanouk was more strongly placed (see below), and increasingly hostile to nationalists and leftists such as the Japanese-era Prime Minister Son Ngoc Thanh whom he saw as opponents of the monarchy. Most had chosen or been forced to flee to Viet Nam or the border area in the early 1950s, and Sihanouk used his position to propel himself into the position which constitutional democracy should have occupied.

The 1950s experiments in democracy, for which only the Philippines had been adequately prepared, look reasonably successful in relation to the magnitude of the task, and by comparison with what came before or after. They managed to keep extremely fragile and unlikely new states intact, gained rapid international legitimacy and support, developed radically new education systems around a newly defined national identity, and even delivered significant economic growth. Yet having promised so much more than the now reviled colonial systems, they could deliver much less of stability and physical security. The results of elections seemed pedestrian, corrupt, and parochial by contrast with the heady, emotive leadership of the transition to independence. Only the communists appeared able to persuade mass voters to choose a coherent political platform, and their success alarmed religious and economic elites. Those marginalized by elections began again to voice ideas about the unsuitability of liberal democracy for their local conditions. Some of those who believed they had an entitlement to rule would welcome these discontents as a chance to act.

Guns Inherit the Revolutions

The forces with enough internal discipline and external ruthlessness to overcome rivals and impose their own vision as the national one were best placed to inherit the revolutions. The military and the communists were not always the two toughest competitors on the ground, but the Cold War made it difficult for other players with more comprehensive or pluralist visions to survive. In this context what seems surprising is how long it took the communists (in Viet Nam, Laos, and Cambodia) or the military to achieve that dominance. Democracy endured for a decade not just because it was the global gold standard, but because the intense pluralities in each country could not be contained in any other ring.

The other factor, however, was the unpreparedness of either communists or soldiers to take over at a national level. Unlike the communist party of China, those of Southeast Asia had been crushed by colonials or Japanese since 1926, and had at most a few years of experience since regrouping. The people with the guns were extraordinarily divided, and mostly in their twenties, with negligible strategic or technical training. Only Thailand had a long tradition of a national army, which had already inherited the 1932 revolution when Field Marshall Phibun Songkhram became the increasingly authoritarian Prime Minister in 1938. As noted in the previous chapter, he was eased out in the necessarily anti-fascist atmosphere of 1945, but returned to the Prime Ministership in another military coup in November 1947. The intervening period of Pridi’s dominance had been one of Thailand’s most liberal, when a fully elected legislature was finally inaugurated, and laws were passed against military involvement in politics. Pridi even made peace with the royalists and invited King Ananda Mahidol to return for his twentieth birthday. When the king was mysteriously killed, however, the royalists and militarists found a pretext to unite in support of a coup, manufacturing some rumours that Pridi was responsible for regicide.

Thailand’s was the only army at this stage with enough centralization and technical competence to become the backbone of state government. By doing so it established a model for those that would follow, making military rule appear respectable and even desirable in the growing Cold War confrontation with communism. Washington had declined to embrace Phibun after his 1947 coup, but began to fund Thailand as a strategic Asian ally immediately after the communist victory in China. At the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Phibun’s government was the first in Asia to offer military support to the United States, and was rewarded with further military aid. The army was thereby emboldened to dispense with its uncomfortable royalist allies and take over government in the 1951 coup. It cemented its strong relationship with Washington by cracking down on the remaining liberals and leftists in Thailand’s public sphere. For Phibun the alliance was needed not against the negligible communist party, but as internal legitimation, and strengthening against traditional rivals Viet Nam and Burma. However, US military aid to the army, and CIA support for the police, strengthened these two rival networks of patronage to the extent of undermining Phibun’s control. He responded with another round of liberalization, ensuring that his allies won a flawed election in 1957. The army, now led by Field Marshall Sarit Thannarat (1908–63) and General Thanom Kittikachorn (1911–2004), shifted to a more blatant military dictatorship in two coups of 1957 and 1958. Sarit ruled as Prime Minister until his death, and Thanom thereafter until the pro-democracy movement of 1973. Wholly Thai-educated, these generals were unapologetic in declaring democracy unsuited to Thailand, preferring an imagined harmonious order under the old monarchy. During America’s Indochina wars, Thailand became its essential base for bombing raids, vital supplies, Thai troops deployed in Viet Nam and Laos, and a congenial rest and recreation center for its troops. Military-backed “development” was touted as the only viable model for growth short of communism.

Burma’s determined policy of neutrality in the Cold War did not prevent its becoming the second of Southeast Asia’s military dictatorships, in 1962. Like Indonesia’s, Burma’s armed force, the Tatmadaw, believed itself an heir to the revolutionary struggle against Japanese and British, essential to the survival of the state. Its units were more accustomed to sustaining themselves by rent-seeking in legal and illegal business than to control by civilian paymasters. By 1956 it had achieved a unified command of the three services under General Ne Win, fellow-Thakin of Aung San and U Nu. The civilian politicians, by contrast, had been in disarray since Aung San’s assassination in 1947, with the ruling AFPFL appearing an ever more dysfunctional and corrupt coalition, up to its eventual split in 1958. Under pressure from Ne Win, Prime Minister U Nu then agreed to hand authority to a caretaker government led by Ne Win and the Tatmadaw, simply to deal with the temporary crisis in six months. Ne Win had this period extended until elections in 1960, but meanwhile gave an appearance of purposefulness in cleaning up Rangoon, fighting the communists, controlling prices, and replacing discredited politicians and Shan and Karen traditional chiefs.

U Nu’s faction of the AFPFL won the 1960 election easily, helped by the aura of Aung San and Nu, the promise of making Buddhism the state religion, and some strong-arming from the military. The last Nu government appeared more chaotic and incompetent than ever, as his divisive push for a Buddhist Burma took most of his interest. The Tatmadaw, committed to a centralized revolutionary vision, was particularly disturbed by U Nu’s attempt to accommodate the Shan sawbwas, whom Ne Win’s first stage in power had pushed side, and who now threatened departure from the Burma Union unless there was a transition to federalism. Ne Win launched his military coup on March 2, 1962, arresting the cabinet and dismissing the Parliament. Declaring that parliamentary democracy had been proven unsuitable to Burma, the Tatmadaw proclaimed its own “Burmese Way to Socialism,” which would have a single state party, nationalization of all key sectors of the economy, and state control of land, but would be superior to Marxism-Leninism in representing all of Burmese society, not only workers and peasants. Though beginning with some high-sounding reversal of Nu’s policies on Buddhism, the press, and minority relations, it quickly moved to monopolistic total control of the press, and crackdowns on any expressions of opposition. Whatever claims it had to revolutionary legitimacy were lost in May 1962, when troops invaded Rangoon university to suppress political activity, and in the ensuing melee killed over a hundred students and blew up the Student Union building, hallowed site of the nationalist movement of the 1930s. The Tatmadaw established Southeast Asia’s most enduring and uncompromising military dictatorship, in the name of the Revolutionary Council (from 1962), the Burma Socialist Program Party state party (BSPP, progressively from 1971), and the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) after a brief democratic experiment in 1988. These governments responded to the Cold War with a neutrality that involved drastically reducing foreign engagement, training, and assistance, and securing their long endangered boundary with China by carefully avoiding public disagreements with Beijing.

Indonesia’s armed forces (ABRI) had similar revolutionary habits of engagement in the country’s political and economic life, but none of the taste or opportunity for isolationism. In 1950 it also lacked any leader of comparable political stature to Ne Win. The choice of the Japanese-trained officers for leadership, General Sudirman, had died in 1950. The young Dutch-trained colonels to whom the Jakarta government gave the task of building a disciplined modern force, Nasution and Simatupang, were sacrificed after the October 1952 affair, an abortive army attempt to prevent political interference in its affairs by abolishing Parliament. Nasution was brought back as Chief of Staff of ABRI in late 1955, after a series of crises had consolidated army support behind him. Jakarta could not, however, control its colonels in command of wealthy districts outside Java, who resented the growing pressure for military and economic centralization that threatened their soldiers’ livelihood from semi-legal “informal” trade to Singapore, Malaya, and the Philippines. They also distrusted the growing power of the Java-based PKI after the 1955 election, and Sukarno’s desire to include the communists in government. The growing polarization marked by the resignation in December 1956 of Vice-President Hatta, Sumatran, anti-communist, and pragmatist, also propelled the dissident colonels toward open rebellion.

A state of emergency, proclaimed in 1957 to deal with this regional threat and with the confiscation of Dutch assets under nationalist and communist pressure, legalized and extended the power of the military in every region. ABRI moved quickly to take over Dutch plantations and businesses, and to prevent the PKI doing so through its militant unions. These assets ensured that the military would be able to sustain itself independent of the civilian government, and that the officer corps had a major interest in the continuation of emergency conditions that justified this privileged position. When the dissident colonels allied with some Masjumi and socialist politicians to proclaim an alternative “Revolutionary Government of Indonesia” (PRRI) in 1958, Sukarno and Nasution moved decisively to use Java troops to crush the rebel units in Sumatra and North Sulawesi. Although elite officers and politicians were treated mildly, dismissed or exiled rather than executed, some 35,000 men died on both sides of the battlefield. The Army extended its role in political and economic matters, particularly in the ex-rebel provinces of Sumatra and Sulawesi occupied by Javanese units. It became more centralized, more ready to use violence domestically, and more Javanese (about 80% of the top officer corps by 1970), as officers from Sumatra and Sulawesi were dismissed or marginalized.

Through these crises, between the declaration of martial law in 1957 and the return to the authoritarian 1945 Constitution in 1959, the army grew steadily more powerful at the center as well as in the regions. Sukarno also grew more powerful with each crisis, preaching revolutionary unity as against the divisiveness of parliamentary democracy. When the Constituent Assembly declined his proposal to reinstate the emergency 1945 Constitution he summarily dismissed that Assembly and proclaimed that constitution on his own authority, making the cabinet responsible only to himself. His attacks on the parliamentary system were designed to appeal to the armed forces as well as the communists. “The instruments of state power must be completely weaned from liberalism, now that they are in the shade of the flag of the 1945 Constitution. They must now become instruments of the Revolution again” (Sukarno 1959, cited Feith and Castles 1970, 107). ABRI’s centrality in the system of “Guided Democracy” Sukarno inaugurated was demonstrated when the military filled one third of cabinet positions, including Nasution as Defense Minister, and many governorships.

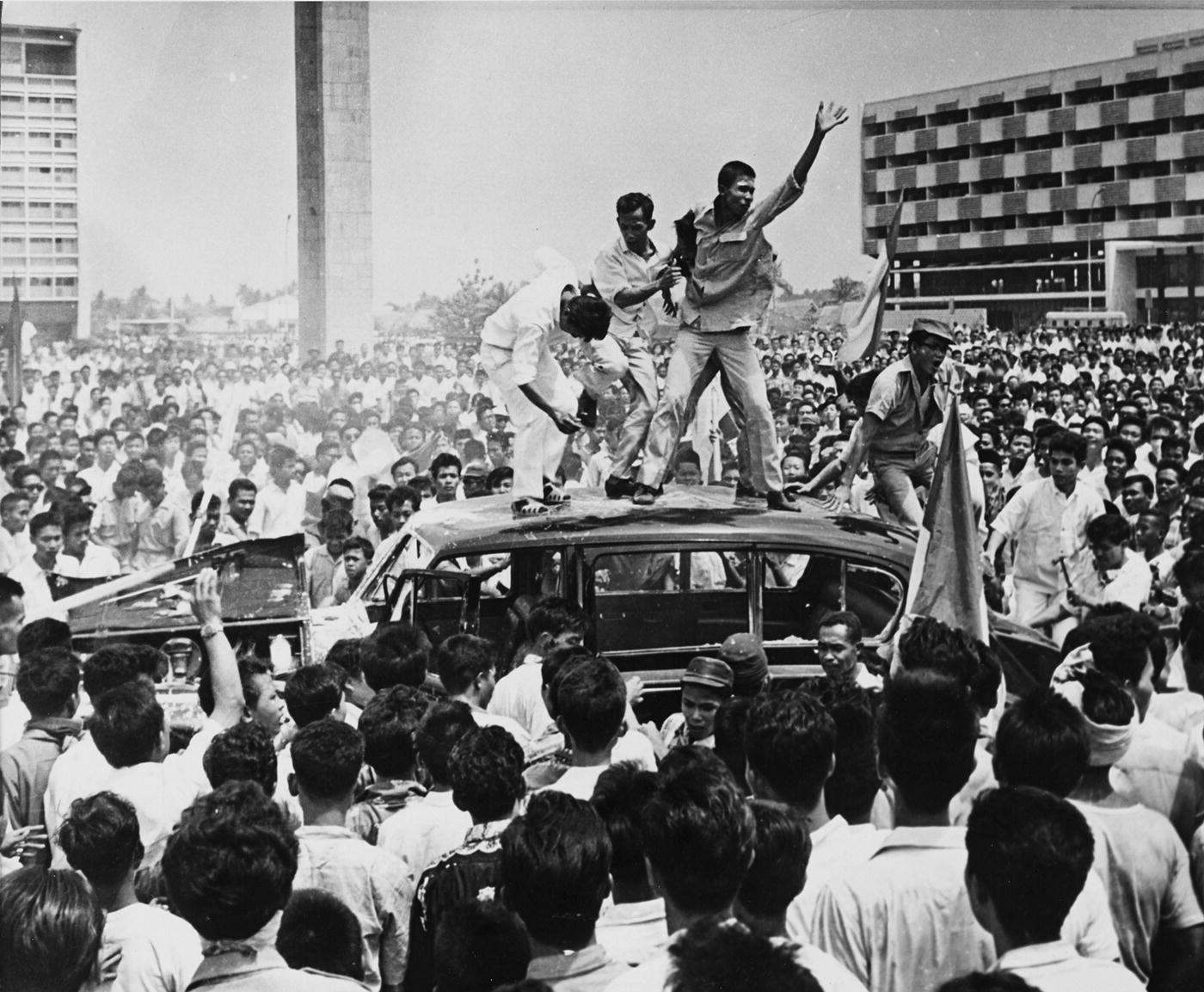

Military power was allowed to override constitutional propriety by the continuing state of emergency, justified by an aggressive campaign to force the Dutch to yield West New Guinea (later renamed West Irian, Irian Jaya, and West Papua in turn) to Indonesia. The campaign ruptured all relations with the Netherlands and culminated in armed infiltration. Encouraged by the United States, the Netherlands decided in 1962 it had more to lose by resisting this pressure than by abandoning the Papuans in its care, and agreed to a UN-supervised transfer of power to Indonesia. The military, Sukarno, and the PKI had all benefited from this campaign, and found another reason to maintain emergency government by “confronting” the formation of Malaysia in 1963 (see below). Neither British nor Malaysian government were likely to concede as the Dutch had done, however. International opinion roundly condemned Indonesia’s “crush Malaysia” campaign, leading Sukarno to take Indonesia out of the United Nations in January 1965 and increasingly to align with China. The PKI was the most vociferous supporter of crushing Malaysia, able to mobilize mass demonstrations in favor of Sukarno and against Malaysia and the British (Figure 17.1). It sought to have “volunteers” armed and trained for the struggle, outside the control of the army command. Despite rivalry between the blunt Defense Minister Nasution and the more pliable Javanese General Achmad Yani who had replaced him as Chief of Staff, the army leadership again saw the PKI as its primary enemy and secretly maintained contacts with the United States and Malaysia. Polarization was also rising again in the countryside, where the PKI mobilized landless peasants to insist on the implementation of a land reform already agreed by Parliament, to the extent of unilaterally occupying the land of richer peasants. Muslim (chiefly NU) youth were mobilized to oppose such actions, and bloody clashes became increasingly frequent through 1965.

Figure 17.1 Anti-Malaysia demonstration, Jakarta, 1963. Demonstrators are standing on the roof of the British Ambassador’s car, having pushed it out of the Embassy grounds.

Source: AP/Topfoto.co.uk.

In an atmosphere of economic collapse, exaggerated revolutionary rhetoric, and rumors of coups after Sukarno had a sudden bout of illness on August 4, a coup did take place against the army leadership on the night of September 30, 1965. Achmad Yani and five of his general staff were captured and killed, while Nasution managed to escape by scaling the wall of his neighbor. The coup was the work of a Revolutionary Council led by Lt Col Untung, an officer of Sukarno’s palace guard, seemingly aimed at obtaining the support of air force, navy, and police as well as disgruntled lower ranks in the army against a “Council of Generals” who were “power-crazy, neglecting the welfare of their troops, living in luxury over the sufferings of their troops,” according to Untung’s first announcement, as well as in league with the CIA. Untung was clearly a Sukarnoist, and probably believed that Sukarno wanted to find a way around his “disloyal” generals. The action appeared to have implicit support from the air force commander Omar Dhani and the PKI leader D.N. Aidit, both of whom were at the Halim airport where the coup group gathered, and who issued generally supportive but uninvolved statements during the following day. Sukarno himself also went to Halim believing the action was to protect him, though he avoided any public endorsement before news of the bungled murders and of the army’s recovery made that unwise.

Major General Suharto (1921–2008) was the most striking omission from Untung’s targets, as commander of the Jakarta-based army strategic reserve (KOSTRAD), often deputizing for Yani. There were several reasons the plotters assumed he was a loyal Sukarnoist, not opposed to the President’s move to the left: he had in 1948 been sent by General Sudirman to mediate with the communists involved in the Madiun uprising (rather than confronting them); he had a grievance against Nasution, who had relieved him of the Central Java command in 1959 on the grounds of his raising funds by dubious dealings; he had been a patron of Untung in Central Java, and later in the command to “liberate” New Guinea, and had attended Untung’s wedding; he was close to another key plotter, Colonel Latief, who visited him at his son’s bedside in hospital on the evening of the coup (and was never put on trial for his role, suggesting the danger of implicating Suharto); and he was a reserved Javanese not given to outspoken comment. If they expected him to support the move, however, the plotters were badly mistaken. He moved early on the morning of October 1 to have his KOSTRAD troops take over the radio station and the central Merdeka square from the coup group, and by evening could announce on the radio that he had taken command of the army, and that together with the navy and air force they were determined to crush the “30th September movement” and protect Sukarno from it.

Once Suharto’s forces had captured the coup base at Halim airport the next day and found the bodies of the murdered generals, Suharto began a campaign to destroy the PKI under the thin legal veil of Presidential authority to “restore order.” Army agents encouraged Muslim and Catholic youth groups best known for opposing the PKI advance to form an “Action Front” against the coup. As word spread that the army was on their side, anti-communist demonstrations quickly followed, leading to the burning of the PKI headquarters in Jakarta on October 8, later emulated elsewhere. Despite constant appeals by Sukarno for a political compromise, the army seized and summarily executed all the communist leaders they could find. Aidit and cabinet minister Njoto were killed in November. Only a handful of PKI leaders, and Untung himself, were kept alive for subsequent public military trial. Sukarno’s charisma alone was not enough to counter the military without the PKI to represent mass support. Although maneuvering constantly to defend the PKI and maintain a cabinet loyal to him, he was finally forced to capitulate on March 11, 1966, when troops surrounded the palace during a cabinet meeting, in an atmosphere of unprecedented demonstrations against the President. Sukarno signed a letter instructing Suharto “to take all measures considered necessary to guarantee security, calm and stability of the government and the revolution.” Suharto now used this cover of Presidential authority to ban the (already-destroyed) communist party, arrest the Leftist or Sukarnoist members of cabinet, and reshuffle military appointments to support the anti-communist stance. Carefully avoiding any direct criticism of Sukarno, Suharto did not replace him as “Acting President” until a year later, resisting many harsher voices demanding his impeachment for participation in the 1965 coup (Figure 17.2). It was a military coup by instalments, but a carefully camouflaged one.

Figure 17.2 President Sukarno and General Suharto in February 1967.

Source: Associated Press/Topfoto.

It was also far more – a massive bloodletting that ended the conflicting revolutionary dreams, and established a state with an iron fist. Mass killing of not only cadres but entire families of PKI sympathizers began in October in Aceh, where the party had represented a significant voice for unpopular Jakarta policies of secularism and centralization. In Central Java, where the PKI was strongest, the tough anti-communist Colonel Sarwo Edhie quickly trained and armed members of anti-communist Muslim groups to do the work of rounding up and killing PKI activists. The pattern was repeated in East Java, where the NU youth group Ansor did most of the killing. But even without the Muslim factor, in Bali, sufficient tension had arisen over the PKI challenge to village hierarchies that pro-nationalist youth felt entitled to slaughter thousands of their rivals. The best argument against the army’s well-publicized and later enforced interpretation that the PKI was responsible for the September 30 coup was the complete communist unpreparedness for an armed struggle of any kind. The Party’s link to the military coup plotters through a suspected double-agent called Sjam was known to very few PKI leaders, and even they had no control over the likes of Untung. Nevertheless, the whole left wing of Indonesian politics, which had appeared to be rising unstoppably in influence, was ruthlessly crushed. How many died cannot be known, though a figure of a half-million has become widely accepted. Half or more of the total died in East Java, though the highest proportion to population was probably in Bali, and every province had its victims. A larger number were imprisoned and subject to interrogation and torture, and even after release were denied state employment and voting rights. About 12,000 were sent to a penal colony in underdeveloped Buru Island (Maluku) until its closure in 1979.

Suharto remained in power until 1998, and gradually relied less on terror and more on legal and bureaucratic means of control. His regime turned the economy around and allowed it to grow at a pace unknown since records began. It created a “one plus” party system of which Sukarno had only dreamed, whereby a favored government party, Golkar, guaranteed safe parliamentary majorities and the return of bureaucratic hierarchies undermined since 1942. Indonesia swiftly made peace with Malaysia and Singapore, rejoined the United Nations, and became a reliable member of international organizations. Internally it imposed a single, centralized education system and syllabus, defining the fruit of the revolution as being a unitary state coinciding with the boundaries of Netherlands India. Liberal parliamentary democracy and federalism remained condemned, as under Sukarno’s Guided Democracy, but Suharto was able to ensure that rival ideas were not heard, where Sukarno could only keep them in unstable balance. These changes came with an appalling cost in lives and liberties, but they delivered a unified nation-state.

Viet Nam, Cambodia, and Laos were never models of democratic governance, but it was significant of the times that there, too, there was a phase of military coups and rule by the gun. General Duong Van Minh took power in South Viet Nam in November 1963, in a coup at least condoned by the American protector. Although the coup was discredited from the outset by the murder of the incumbent president, Ngo Dinh Diem (1901–63), military governments succeeded one another thereafter until the fall of the regime to the communist DRV in 1975, having little but force and US backing to sustain them. In Cambodia military commander Lon Nol seized power from King Sihanouk during his absence in Paris in 1970, complaining that his neutralism allowed too much latitude to North Vietnamese forces in the east. He ruled as President until this country too was taken over by communist forces five years later. The Royal Lao Army, in contrast to its Pathet Lao enemy, paid little heed to the civilian government of Prince Souvanna Phouma in the 1960s. The commanders of each district became in effect warlords controlling the local economies including the drug trade on one hand, and accepting US military support directly on the other.

Why were the 1960s so congenial to military rule? The superficial answer is the Cold War – the United States sought dependably anti-communist allies at a peak moment of communist success. The country cases show, however, that the American role was marginal to the political dynamic, usually limited to a quiet nod that support would not be withdrawn if the military took power. Fundamentally, the revolutionary process had aroused passions about national sovereignty that were a poor fit with existing political communities. No less than the whole of the arbitrarily defined imperial spaces could satisfy as the goal of national struggle, but only force, and perhaps not even force, could control the diverse demands aroused in that space. Some influential political scientists of the time went further, arguing that in the conditions of the new countries only the military had the “strong leadership backed by organizational structure and by moral authority” to act as effective agents of state-building and modernization (Pauker 1959, 343; also Johnson 1962). But the military record in government was generally worse than that of the civilians who preceded, with only the Indonesian case having much on the positive side of the ledger.

Dictatorship Philippine Style

Even Southeast Asia’s most robust parliamentary democracy had its authoritarian moment in the 1970s. The Philippines had had an educated middle class since the 1870s, its revolutionary moment of self-definition in the 1890s, and a free press and American-style electoral democracy since the 1920s, which regularly threw out incumbents in a tradition of rivalry among the great propertied families. The constitution limited the President to two terms, but none had won a second election until Ferdinand Marcos (1917–89) came to the Presidency in 1965. With his beauty queen wife Imelda he promoted a populist personality cult like no other, and claimed to be changing the old elite family politics by bypassing Congress to borrow money for major public works and expansion of the military. The Cold War indulgence of military dictators was a factor in his rise, since he had earned Washington’s approval by controversially sending Philippine military engineers to support the US fight in Viet Nam in 1966. As if on cue, a communist threat emerged soon after his big-spending success in the 1969 election, in the form of a Mao-inspired and reconstituted Communist Party of the Philippines. In 1972 the Moro National Liberation Front began a rebellion in the Muslim south.

This radicalized atmosphere was Marcos’ justification for declaring martial law in 1972. Claiming the need and opportunity to surpass the “familiar and mediocre past,” he ruled by decree, imprisoned vocal opponents such as Senator Benigno (“Ninoy”) Aquino (1932–83), confiscated many assets of the old elite, suspended Congress, and installed military officers, technocrats, and his own favorites in key positions. A constitutional convention was persuaded to write a new constitution, allowing Marcos to continue in power beyond his term in 1973. The armed forces were kept on side by a tripling of their budget and manpower between 1972 and 1976 and a centralization of the command structure. Military aid flowed generously from the United States. Many Philippine intellectuals began to think that the communists had a point in targeting the “neo-colonial” US alliance as the problem.

While Marcos’ “New Society” emulated some of the rhetoric, the electoral and legal coercion, and the extrajudicial killings of Suharto’s “New Order,” he notably failed to match Indonesia’s 7% annual growth rates. Indeed it was under martial law that the Philippines began its late twentieth-century pattern of economic underperformance and stagnation. The populist support that had flowed from his attack on the ruling oligarchy eroded in face of the rising burden of debt from his projects, and the corruption (increasingly public in the 1980s) that outrageously enriched his own family and his close cronies. Controlled elections (boycotted by the opposition) were reintroduced for Congress in 1978 and for President in 1981, after martial law had been lifted prior to a first visit by the Pope to this most Catholic of Asian countries. As an ailing Marcos increasingly appeared to lose control to his flamboyant wife and military favorites, his leading critic, Ninoy Aquino, was assassinated very publicly at the Manila airport on his return from American exile in 1983. This extraordinary blunder turned the world as well as the Philippines against Marcos. He attempted to stem the tide of protest with a snap election for February 1986, in which Aquino’s modest widow, Corazon (“Cory”; 1933–2009), bravely led the opposition. As usual it was declared a Marcos victory, but the energized people of Manila, the Catholic Church and the commander of the Philippine Constabulary, Fidel Ramos, all believed it was stolen and that Marcos had to go. Two weeks later “People Power” propelled Marcos and his wife to exile in Hawaii and Cory Aquino into Malacañang Palace as Southeast Asia’s first female head of state and government. Her key ally in that vital uprising, General Fidel Ramos, succeeded her in 1992. Between them they re-established a democratic constitution, less corrupt administration, civil liberties, and the return to modest economic growth. It was also a return to politics as usual, as the dominant families quickly resumed their pattern of control of the legislature.

Remaking “Protected” Monarchies

In Chapter 11 we noted how those monarchical systems closest to modernizing into states – Burma, Viet Nam, Aceh, and the Balinese rajas – were those hardest for expanding European empires to deal with in the nineteenth century, resulting in their eventual brutal conquest. Those Malay, Tai, and Khmer monarchs accustomed to drawing their revenue essentially from entrepreneurial foreigners, and to sending deferential tribute where necessary to stronger trading partners, found the transition to colonial rule much gentler and less disruptive. Their weakness in legal-bureaucratic terms was their strength. In 1945 they were still clinging to fragile thrones, endangered by their collaboration with the Japanese on the one hand, and Marxist-influenced demands for the end of “feudalism” on the other. Their survival in the Malay world, Thailand, and Cambodia is one of the surprises of the mid-century crisis. It owes much to the quest of conservatives for a barrier against the unknown perils of populism and Marxism, but perhaps more to the simple immensity of the challenge of turning multi-ethnic and cosmopolitan imperial space into a nation-state. In the absence of political community, charisma was a precious commodity.

The Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia (Chapter 16) was a shock for both rajas and their opponents. In principle the Japanese had no time for divided or qualified sovereignty, and favored the slogan of the Meiji restoration – hanseki hokan (all domains yield to one sovereignty). In practice they naturally worked with any influential figures who professed to support their aims, and that of course included many rajas. But the very fact of one sudden and radical change of regime in 1942 and another in 1945 encouraged the hopes of all who opposed the status quo, and thereby turned rivalries and personal conflicts into deadly choices. In Langkat (East Sumatra) the Japanese were met with slogans demanding the end of monarchy. Where royal families were deeply split by succession disputes, the Japanese advent offered a chance for changing the incumbent, risking reversal and further embitterment when the Japanese departed. In Laos the readiness of one prince to embrace the doomed Vichy regime, and his rival to embrace the Japanese who ruled directly for less than a year, bedevilled subsequent royal politics. In Selangor (Malaya) the Japanese replaced the sultan by his more popular brother, whom the British in turn arrested and exiled in 1945. Everywhere the charisma of royalty was profoundly damaged by the way Japanese officers disregarded the formal status of nominal kings, obliging them to share the propaganda spotlight with nationalist politicians who despised them, and even to give a public example of “voluntary labor” for the Japanese cause. Only a few of the youngest western-educated rulers, notably Norodom Sihanouk in Cambodia and Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX (1922–88) in Yogyakarta, could adapt to the populist style expected by the Japanese, but this served them well in facing the trials of nationalism to follow.

The sudden Japanese surrender in 1945 created further crisis, particularly where the colonial regime could not re-establish itself. Several of the rulers were too quick to make public their eagerness for the restoration of the old regime, and too slow to look for protection from the nationalists. In East Sumatra a radical alliance of Marxists, nationalists, and ethnic rivals attacked the palaces of the once-wealthy Malay rajas in March 1946, killing hundreds of aristocrats and capturing the rest in what was dubbed a “social revolution” in the name of popular sovereignty. In Yogyakarta, by contrast, Hamengkubuwono astutely invited the Republican government to transfer its capital to his, away from Dutch control in Jakarta, establishing thereby a solid alliance with nationalism. By contrast, his perennial royal rivals in Surakarta focused the animosity of the radicals, and suffered another “social revolution” in July 1946. The Republic took a firm stand against the remaining monarchies with the sole exception of Yogyakarta. Once it assumed responsibility from the Dutch for the whole Archipelago with its many and varied rulers, these were eased out of power without serious violence in the 1950s. The most influential of them, in Sulawesi and the other eastern islands, made the transition by becoming the first of the Republic’s district officials (bupati). The prevailing rhetoric in Indonesia, as in Indochina, was to regard “feudalism” as akin to colonialism in symbolizing a vanished and despised era.

The British returned to the Peninsula in August 1945 with a new plan to make the messy mix of colonies and protected sultanates acquired over 260 years into a potential national unit, the Malayan Union. All the races living there would have an equal stake as citizens, but Singapore would be separated as an Anglo-Chinese commercial hub and military base. This new “Malayan” identity could only be achieved if the sultans agreed to surrender their nominal sovereignty, a task made much easier by their vulnerability as collaborators with the Japanese enemy. Sir Harold MacMichael achieved this task in October 1945, reversing the pre-war alliance with the Malay elite in recognition of Chinese sacrifice during the war. In Sarawak a similar cession of sovereignty was enforced, from the Brooke family rulers to the British crown, resulting in an increasingly violent anti-cession movement culminating in the murder of the second colonial governor in 1949. In Malaya, too, outrage gradually spread among a hitherto quiescent Malay population against the loss of Malay sovereignty, but more emotively against the plan’s acceptance of the majority of the large and energetic Chinese population as equal citizens.

The better-educated aristocrats of the nine Malay states became mobilized in an unprecedented series of national-level meetings, culminating in the formation of a United Malays National Organization (UMNO) in March 1946. Though dedicated to opposing the Union and restoring pre-war Malay sovereignty and privilege, its very existence showed that everything had changed. In standing up to the sultans, and forcing them, unprecedentedly, to boycott the ceremony installing the first governor of the Malayan Union in April, UMNO shifted the object of protection and loyalty from the sultans to the race – the bangsa Melayu (Malay race or nation). This was explicitly opposed to the vision of a multi-racial citizenship and eventual identity as bangsa Malayan, a term UMNO leaders denounced as an incongruous British creation supported only by non-Malays. Thus was born the most enduring of Southeast Asian’s ethno-nationalisms, sustained by its most enduring ruling party, UMNO.

The British felt obliged to yield, since the Malay opposition to the Union had been so apparently united, while potential supporters of it were divided between the strong but increasingly anti-British communists, anti-establishment Malays attracted to the “Greater Indonesia” idea, Chinese and Indian nationalists, and English-educated “Straits Chinese” opposed to separating Penang from Singapore. UMNO and the rulers now demanded an exclusively “Malay” federation of states in which non-Malays were tolerated but had no political rights. In Anglo-Malay negotiations for a new compromise, Malay representatives insisted on retaining “Malay” as the only valid nationality, whereas they “took the strongest objection to being called or referred to as Malayans” (Report of Constitutional Working Committee, 1946, cited Omar 1993, 107). The name of the new country, inaugurated in 1948, became Federation of Malaya in English, but Persekutuan Tanah Melayu (Federation of Malay Lands) in Malay. Nominal sovereignty was returned to each of the nine sultans, though now as explicitly constitutional monarchs obliged to accept federal and state legislation.

This was no recipe for a viable independent state, toward which the British were obliged to move in their competition with the MCP insurgents. The UMNO leader (and Johor Chief Minister), Dato Onn bin Jaafar (1895–1962), was leaned on by the British to find common ground with the Chinese and Indian leadership in the hope of emerging as leader of an independent Malaya. He eventually agreed to concede Federation citizenship to non-Malays, but when he sought to turn UMNO into an inclusive party for all races he was rejected by its members. In 1951 he left the party to form a multi-racial Independence of Malaya Party, which was heavily defeated at the first election in 1955 despite British support. Leadership of the transition to independence passed instead to an Alliance Party made up of three racially exclusive parties – UMNO, the Malayan Chinese Association, and the Malayan Indian Congress.

The constitution negotiated for the independence of the Federation of Malaya in August 1957 was a unique hybrid. So central to Malay ethno-nationalism had the sovereignty of the sultans become that the Federation was constitutionally required to “guarantee the sovereignty of the Malay sultans in their respective states.” Since most matters fell under federal jurisdiction, however, the sultans were still left only with land, local government, and Islam, and even here had to follow the advice of a chief minister responsible to a state parliament. The head of state of the federation was elected for a five-year term by the nine sultans from among themselves, and named Yang di Pertuan Agung, like the long-established elective king of the “nine states” of Negri Sembilan.

The contradiction between Malay and English names of the state was finally resolved when the scholarly neologism “Malaysia” was adopted for the broader federation embracing Sarawak and Sabah (North Borneo). Malaysia was rushed into being in 1962–3 because of the danger of pro-communists coming to power through elections in Singapore. Aided by the British, who imprisoned the popular Chinese leftists who had brought him to power, Lee Kuan Yew managed to sell the idea of Malaysia as the only acceptable route to independence. Sarawak and Sabah were brought on board by the distribution of timber contracts to key ethnic leaders, disproportionately large representation in the Malaysian parliament, control of their own immigration, and a ten-year guarantee of English as their state language. Like Penang and Melaka, their heads of state were governors appointed by the Yang di Pertuan Agung, so that they had no say in choosing the federal head of state. The Malaya constitution was simply amended by act of parliament to add these new states, and the unique features of Malay-style federalism remained. Lee Kuan Yew’s aggressive championing of a “Malaysian Malaysia” of equal rights for all quickly aroused a Malay nationalist reaction, leading to Singapore’s expulsion and independence on August 9, 1965.

Many in the Borneo territories would come to feel that their hasty merger with an already-established Malaya left them at a permanent disadvantage in modernizing on their own terms. The alternative plan favored by many British officials and Indonesian-influenced Muslim politicians was that the two colonies and the British-protected sultanate of Brunei should first establish their own constitutional federation, and then negotiate merger on the basis of equality with Malaya. This idea was not helped, particularly in the eyes of Brunei’s Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin (1914–86, r.1950–67), by being championed by A.M. Azahari (1928–2002). He had returned to Brunei in 1952 from Java, where the Japanese had sent him for training, and three years later established the Brunei People’s Party (PRB), British Borneo’s first. It campaigned in Brunei and London for a constitutional monarchy with a fully elected legislature, and gained popularity by attacking British, and later Malayan, arrogance. When the British and the hitherto theoretically absolute sultan eventually agreed on a constitution with a part-elected legislature, Azahari’s party won all sixteen of its elected seats in September 1962.

The rapid moves to bring all three Borneo territories into Malaysia were attacked by Azahari as a neo-colonial plot to retain British influence, while the sultan worried that he was being rushed into union with states far less Malay-dominated and royalist than his own. PRB could not have been ignored, but the party destroyed itself in a rebellion in December 1962, with some support from Indonesia and Chinese communists in Sarawak. Since Brunei had at the time no army, and the rebels succeeded in taking over most of the police stations (and capturing dozens of Europeans), they may have hoped that a mixture of force and diplomacy would eliminate the colonial presence as in Azahari’s model, the Indonesian revolution. The British however despatched enough troops from Singapore, Sarawak, and nearby Labuan to retake control in three days. The sultan broadcast his condemnation. Azahari was at the time safely in Manila, and eventually took refuge in Jakarta, while many of his supporters preferred Malaysia.

Although the revolt increased the pressure for accepting Malaysia on security grounds, it also left the sultan as the sole voice for Brunei after its elected representatives were arrested or fled. He stubbornly resisted the pressure to join, anxious to safeguard the oil revenues which had transformed Brunei from the poorest to the richest Malay state during his reign, and perhaps to resist Malaysia’s electoral democracy. He preferred the status quo of British protection, but now from a position of vastly greater strength. Britain had already agreed to self-government in 1959, but the constitutional side of the bargain had collapsed. The sultan was in effect the government, and proved stubbornly adept at resisting British pressure to return to a constitutional path. Omar Ali Saifuddin resigned in favor of his son Sultan Bolkiah in 1967, but continued to advise him to distrust the electoral process that had opened the way to Indonesian and Malaysian sympathizers. Singapore, the other awkward residue from the Malaysia push, became a vital supporter of Brunei in its resistance to Malaysian-backed democratization, providing infrastructure and a currency. Britain’s democratic resolve weakened before Brunei’s value as an oil and gas exporter, and the international environment became less hostile in the 1970s. Anxious to withdraw from colonial entanglements, Britain allowed, indeed insisted, that Brunei become independent in 1984 as Southeast Asia’s smallest and richest country, and its only absolute monarchy.

Malay monarchy, touted by its defenders as the indispensable essence of Malayness, appeared to experience the full spectrum of possibilities. Brunei celebrated its difference as a completely palace-centered polity, with more than enough oil revenue to make life comfortable for its Brunei subjects and to import Malaysian Chinese and Filipinos to do most of the work. Its ideology, an emulation of the Thai model, was “Malayness, Islam, monarchy” (Melayu, Islam, Beraja). Indonesia, by contrast, had almost totally rid itself of monarchy in the revolutionary 1940s and 1950s, and even the exception, Sultan Hamengkubuwono IX in Yogyakarta, declared that his kingdom would end with his death. But that did not happen in the very different climate under Suharto, whom the sultan helped legitimate as his first economic minister and then Vice-President (1973–8). His successors as sultan remained unelected rulers of Yogyakarta even in an increasingly democratic era. Throughout the Archipelago, the descendants of rulers used first Suharto’s hierarchic authoritarianism, and then the post-1998 devolution of power to districts, to make a comeback as political and cultural leaders.

In Malaysia the incongruous privileges of the rulers continued through independence and democracy. Only Dr Mahathir, Prime Minister from 1981 to 2003, felt strong enough to curb these privileges. He had the constitution changed in 1983 to oblige the rulers to sign any bill presented by federal or state parliament within 30 days; and in 1993 to remove judicial immunity and other perks of office. Control of the press enabled him to reveal a flood of royal scandals at the right moment to shame the rulers into complying. Yet because Malay nationalism found much of its legitimacy in the idea of historic Malay sovereignty and “protected” privilege, the sultans frequently bounced back. Opposition leader Karpal Singh was convicted of sedition in 2014 for having questioned the Sultan of Perak’s controversial appointment of an UMNO Chief Minister without a parliamentary vote of no confidence in his opposition predecessor. Whereas revolutions in the Philippines (earlier), Indonesia, and Viet Nam had sacralized the nation, its heroes, and symbols, as a new form of charismatic legitimacy, the other countries found it difficult to manage without monarchy.

Twilight of the Indochina Kings

Although their historic domains fitted better the boundaries of nationalist aspirations, the kings of Indochina came to a more pathetic end. Emperor Bao Dai (1913–97) had already achieved the long-cherished goal of uniting the three French territories of Tongking, Annam, and Cochin-China into a nominally independent Vietnamese kingdom, under Japanese auspices in 1945. Ho Chi Minh acknowledged his symbolic power by incorporating him as “advisor” in the Vietminh government of September 1945. But when he took refuge in Hong Kong the following year and gradually became the focus of anti-communist nationalist hopes, the communists systematically vilified him. In April 1949 the French lured him back on terms similar to those of Japan – head of state of a nominally independent, united Viet Nam. His government achieved many hard-won concessions and transfers of practical authority, but too many French officials were anxious about their own pride and dignity after the war to allow Bao Dai the major symbolic victories that would enable him to rival Ho in charisma. After the 1954 Geneva agreements he remained as head of state of South Viet Nam only for a year. His stern Prime Minister, Ngo Dinh Diem, wanting no division of his authority, then manipulated a referendum to replace him by a Diem Presidency. The scion of the once-mighty Nguyen Dynasty retired to a relaxed lifestyle in Monaco.

Only one of the many Lao muang, Luang Prabang, had a continuous history through the nineteenth-century partition into Siamese and French territories. Its French-protected ruler, the ailing King Sisavong Vong (b.1885, r.1904–59), was, like Bao Dai, called first by the Japanese in April 1945, then by the French a year later, to represent as king a whole new nation-state. He, however, was resolutely pro-French, and wanted nothing to do with Lao attempts to make their independence real after the Japanese surrender. Most of the leading French-educated nationalists came from the second great family of Luang Prabang, that of the uparit or viceroy. Its forceful Prince Phetsarath (1890–1959), the leading Lao figure under France, Prime Minister under the Japanese and leader of the Lao Issarak (“Free Lao”) nationalist movement, declared in September 1945 that Laos remained independent and that its treaties with France were invalidated by France’s failure to protect the country. When the king repudiated all this and tried to dismiss Phetsarath, the Prince convened an assembly to dethrone him. Laos retained this fragile independence until April 1946, in a delicate military balance between the KMT Chinese army theoretically representing the Allies, and questionable pro-Vietminh allies among the urban Vietnamese population. When the French then reoccupied the cities, Phetsarath and the whole Lao Issarak government fled to Thailand, and from there organized a modest resistance.

Sisavong Vong again became king of the whole of Laos as an “autonomous state” in the French Union, but by continuing to live in Luang Prabang he never became an effective symbol of national unity. France was obliged by international pressure and conflict with the Vietminh to make the independence of Laos more meaningful. In 1949 the Lao Issarak leaders returned and took part in the transfer of most authority from France to the royal government. Following elections, a fully independent government was established in 1953. The United States would be its most important supporter thereafter, making Laos per capita the largest global recipient of US aid, but also of US bombing designed to destroy Vietminh bases and supply lines in eastern Laos. The key political players were two more French-educated princes of the Luang Prabang Uparit family – Phetsarath’s younger brother Souvanna Phouma (1901–84), Francophile, with a French wife and an inclusive neutralist approach, and his half-brother (from a commoner mother) Souphanouvong (1909–95), who had a Vietnamese wife and had been the Lao Issarak link to the Vietminh and the military support it rendered. The former was most frequently Prime Minister of Laos, only briefly succeeding in building broader coalitions among the great lowland Lao (Lao Lum) families, whose rivalries were the main obsession of the political process. The latter had presided since 1950 over an insurgent Vietminh-influenced “Free Lao Front,” whose communist-dominated revolutionary government became known as Pathet Lao (“The land of the Lao”). Because it was forced to rely on highland minorities who collectively outnumbered the Lao Lum, the Pathet Lao was unprecedentedly inclusive of them in its organization. Their support, together with tough Leninist organization and much North Vietnamese assistance, ensured their 1975 victory in the tragic polarization of the Cold War. Both King Sisavang Vatthana (who had succeeded his father in 1959) and Souvanna Phouma stayed in Laos, giving the communist government an initial veneer of legality amid short-lived hopes of reconciliation and peace. Six months later the Pathet Lao organized a more orthodox communist government, and the king was persuaded to abdicate. In March 1976, he and all his family were taken to one of many notorious “re-education camps” near the Vietnamese border, where they died obscurely some years later in conditions that remain unclear.

Miraculously, King Norodom Sihanouk (1922–2012) survived. His royalist Cambodia was the epitome of the modernized Southeast Asian theater state, in which the king was always the star though the sets kept changing, his supporters represented as adoring and his critics evil and treacherous. Other monarchs, and even such flamboyant dictators as Sukarno and Marcos, may well have envied his success in rejecting a constitutional role, manipulating elections, and protecting the rich but hierarchic culture of the court as the essence of the nation, while preserving his country amidst the dangers of the Cold War. Yet in throwing the monarchy into politics, his long career established a pattern from which the Khmer would suffer terribly, even after his death in 2012. He emphasized the uniqueness of the ancient Khmer race and his own ability to represent its “little people,” and rejected any concept of legitimate opposition or criticism.

There was a similar cast of characters in the 1940s to that in Laos, of royalist king and nationalist prime minister being nominally independent under the Japanese, and then jockeying to regain that power under the French. But while King Sihanouk had a more central role than his ageing counterpart in Luang Prabang, the nationalist Son Ngoc Thanh failed to grasp the opportunities of French withdrawal in 1952–3. Instead he left the capital to begin an anti-French insurgency. It was to Sihanouk as king that the French in 1953 handed their remaining powers, notably over the military and foreign affairs. He not only positioned himself as the liberator from colonialism, but appeared to have his anti-colonial cake and eat it, strutting the non-aligned stage in Bandung, befriending China and North Viet Nam, yet having France supply his military training and schoolteachers, and the United States generous amounts of aid. At this moment of euphoria he established a “People’s Socialist Community” (Sangkhum Reastr Niyum) as a state movement that could sweep away conventional competitive politics. He resigned as king so as to head it, and then entrusted notoriously violent supporters to manage the 1955 election in its favor. This crippled the parliamentary system, and ensured that the national assembly comprised exclusively members of the Sangkhum. Although styling himself only Prince, he had himself declared head of state for life in 1963.

Sihanouk’s balancing act could not ultimately survive the advance of the Vietminh and the polarization of Indochina during the Viet Nam War. The Vietminh-backed guerrilla resistance attracted nationalists who saw no other option, but the Khmer communists were inevitably the only organization that mattered within this resistance. Sihanouk himself damaged the economy by a wave of nationalization and the rejection of US aid in 1963, the latter particularly irritating the army. Despite having allied with China and North Viet Nam in 1965 and allowed Vietminh bases in the northeast, his government was nevertheless undermined by the communists. A civil war began in 1967 as unrest grew in the east and Sihanouk encouraged draconian military action against it. When even Sihanouk’s most trusted supporter, the military commander Lon Nol, changed sides, the Assembly removed him as head of state. Sihanouk was then in China, and in horror at this affront accepted Zhou Enlai’s proposal in effect to join the communist side of the civil war to overthrow his usurpers. At home the Cambodian army had to fight an unequal battle to try to expel the Vietminh from Cambodia, while in revenge for its setbacks it allowed Khmer civilians to slaughter Vietnamese in and around the capital. American support for Lon Nol did nothing to slow the military regime’s rapid collapse. Sihanouk’s willingness to travel to communist-held areas in 1973 for photo opportunities with his lifelong enemies may have improved the image of the chauvinist thugs who led the Khmer communists. In 1975 the latter prevailed amidst the US debacle, and Cambodia was plunged into unparalleled misery.

Despite the pathos of Sihanouk’s last decades, as a virtual prisoner in 1975–8 of the appalling Khmer Rouge government he had helped to power, and as an indulged but powerless guest of China and North Korea thereafter, he was again proclaimed king in 1993 by the pro-Vietnamese Hun Sen government. His last abdication and withdrawal to Pyongyang and Beijing occurred amidst illness and powerlessness in 2004. Yet Cambodia remained a kingdom, with one of his many sons on the throne, even though it was the Hun Sen regime that wielded almost absolute power.

Reinventing a Thai Dhammaraja

The Thai monarchy’s reinvention after the mid-century crisis was ultimately the most complete, paradoxically because the royalists began in such a hopeless position that they played their hand with cautiously incremental skill. Since the 1932 coup the kings had been in powerless exile, and competition had been chiefly between two French-educated anti-royalist strong men – Marshal Phibun Songkhram and socialist intellectual Pridi. It was Pridi who first opened the door for a comeback after 1945 to gain royalist help against his military and fascist rivals. Soon after the return to Bangkok in 1946 of the two young brothers, King Ananda and Bhumibol, however, Ananda was found dead in the palace from a single shot from his pistol. This disaster could well have ended the monarchy if its cause were announced as suicide or accident or argument in the family. The cause of death was instead initially hushed up, and later turned to advantage by royalists led by the influential Prince Dhani Nivas, who fostered fantastic rumors that Pridi himself was involved in a murder plot. This helped consolidate an alliance between the royalists and Marshall Phibun, who seized power again in a 1947 coup, and through his 1949 constitution returned many royal privileges taken away in 1932. Eighteen-year-old Bhumibol Adulyadej (b.1928, Cambridge, Massachusets) seemed crushed, and was quickly returned to Switzerland. He only occupied the throne in Bangkok from 1951.

Phibun used the royalists only so long as he needed them, and confined the young king to ceremonial duties in the capital. He took patronage of the Buddhist sangha away from the palace by returning the top jobs in its administration to the Mahayanikai order the revolutionaries had favored since 1932, rather than the royalist-favored Thammayut monks who had resumed authority in the anti-Phibun moment of 1944. He sought to celebrate the 2,500-year anniversary of Buddhism in 1957 as a state rather than royal event, symbolizing reconciliation with republican Burma by inviting its devout premier U Nu to join him in presiding over the extensive ceremonies at Ayutthaya. The lesser role allotted to the king reportedly offended the palace, and Bhumibol boycotted the key event. A few months later General Sarit, previously considered an uncouth and corrupt playboy, gained royal approval for his coup against Phibun. This inaugurated a new phase of unconstitutional authoritarianism publicly justified by restoring royal honor and centrality. The symbols of the 1932 revolution could be removed with the exile of its main defender, the national day was shifted to the king’s birthday, and control of the Buddhist sangha returned to the Thammayut. In the intense Cold War context, the United States welcomed the monarchy’s rise as a more acceptable face for corrupt military dictatorship, and encouraged Bhumibol’s interest in touring the countryside and sponsoring rural development projects.

The following decade of dictatorship and crude Americanization of Bangkok certainly polarized society and encouraged clandestine leftist activity, but it also enhanced the king’s popularity as a symbol of Thai-ness, of decorum, and of concern for his subjects. When in 1973 opposition to the generals boiled over in massive student-led demonstrations demanding a constitution, and the military responding by firing on the crowd and killing 77, the king emerged as a savior of the nation. He demanded that the key generals go into exile, and appointed a civilian prime minister to bring in at last a constitution. The following three years were heady, exciting, but turbulent. Many schools contended to redefine the nation as the Americans abandoned the war in Indochina and scaled down support for the Thai military. With tensions mounting, right-wing paramilitaries and the CIA- and palace-linked Border Patrol Police surrounded the student stronghold of Thammasat University on October 6, 1976, and conducted a gruesome massacre of students darkly etched in national memory. The king endorsed a military takeover and the installation of his favorite general, an anti-communist cold warrior, as prime minister. It appeared that student radicalism had convinced Bhumibol that popular democracy could not be trusted to safeguard the monarchy. The new generation of advisers around him were uniformly conservative, convinced that the country could only be harmonious under a hierarchic order of virtue with the king at its apex, and the military as its guarantor.

The most important of these trusted advisors came to be the relatively clean and astute General Prem Tinsulanond (b.1920), successively army commander (1978), Prime Minister (1980), influential member of the King’s Privy Council when he stepped out of overt politics in 1988, and head of that council in 1998. The alliance between Prem and the palace delivered a “safe” constitution with an appointed senate, and an expanded role for the monarch. The king became champion of rural development designed to undermine communist appeal, star of a series of theatrical celebrations of royal anniversaries, and a pure and virtuous Buddhist king, a dhammaraja. Stability returned with regular elections, and the economy boomed, also in provincial centers where agri-business and manufacturing developed. The governments after Prem’s relied more on increasingly powerful business interests outside Bangkok, and eased the military out of many of its lucrative fiefdoms, prompting another military coup in February 1992, a popular pro-democracy reaction, and another royal intervention in May 1992 to require both military and populist leaders to stop the ensuing violence. This setback appeared to mark a terminal decline in the dominance of the military in Thai politics. Its hold over cabinet and boardrooms collapsed, its share of the budget dropped (from 22% in 1985 to 6% in 2006), and its raison d’être was undermined as Burma and Viet Nam became business opportunities rather than enemies.

The winner in the shifts of power in the 1990s, however, proved to be Thai telecommunications billionaire Thaksin Shinawatra (b.1949), whose parties won unprecedented majorities in elections in 2001, 2005, 2007, and 2011 by implementing policies genuinely helpful to the rural majority, but also by a slick use of the media, money politics, and a popular but extra-legal war on drugs in 2003. Opponents of this novel populism and power concentration in non-military hands had little left to fall back on except the charisma of the king. General Prem and his military supporters were concerned at Thaksin’s attempts (partly blocked by the king) to gain control of military appointments; the ageing king by Thaksin’s popularity and aggressively polarizing style. When another palace-supported military coup in 2006 failed to stop Thaksin’s electoral successes, his opponents took to the streets in the royal color, yellow, and demanded a new way of governing that would keep established hierarchies immune from electoral outcomes. The monarchy was most dangerously politicized by a vastly expanded use of the lèse majesté laws, already tightened in the 1976 lurch to the right, to prevent any discussion of the monarchy’s role or of the military coups it had supported. Although the king himself declared in 2005 that he did not want to be above criticism, prosecutions for lèse majesté increased tenfold in the poisonous atmosphere that followed the 2006 coup, increasingly deployed to silence critics. In June 2014, when military coups were decidedly out of global fashion, Thailand experienced a particularly draconian one. This time the military appeared to gain much establishment and Bangkok middle-class support by promising to eliminate forever the possibility that an electoral majority could overturn their dominance. While at one time a force for stability and moderation, the monarchy had become a key ingredient in Thailand’s disastrous twenty-first-century blind alley.

Monarchy remains a major factor in Thai society and governance, as also in Brunei, Malaysia, and Cambodia in different ways, commanding a charismatic sphere beyond constitutionalism and democracy. It represents not only a link with a vanished past, but a symbol of the right of a few people to rule over many that was strongly challenged by “popular sovereignty” in the 1940s. Those revolutionary memories, along with globalization, education, and post-Cold War democratization, make thrones ever more vulnerable as long as uncertainty remains about their place in a democracy. Even among those elites seeking legitimation to reject majority rule, some Muslims found a globalized scriptural fundamentalism more persuasive than monarchy (Chapter 19).

Communist Authoritarianism

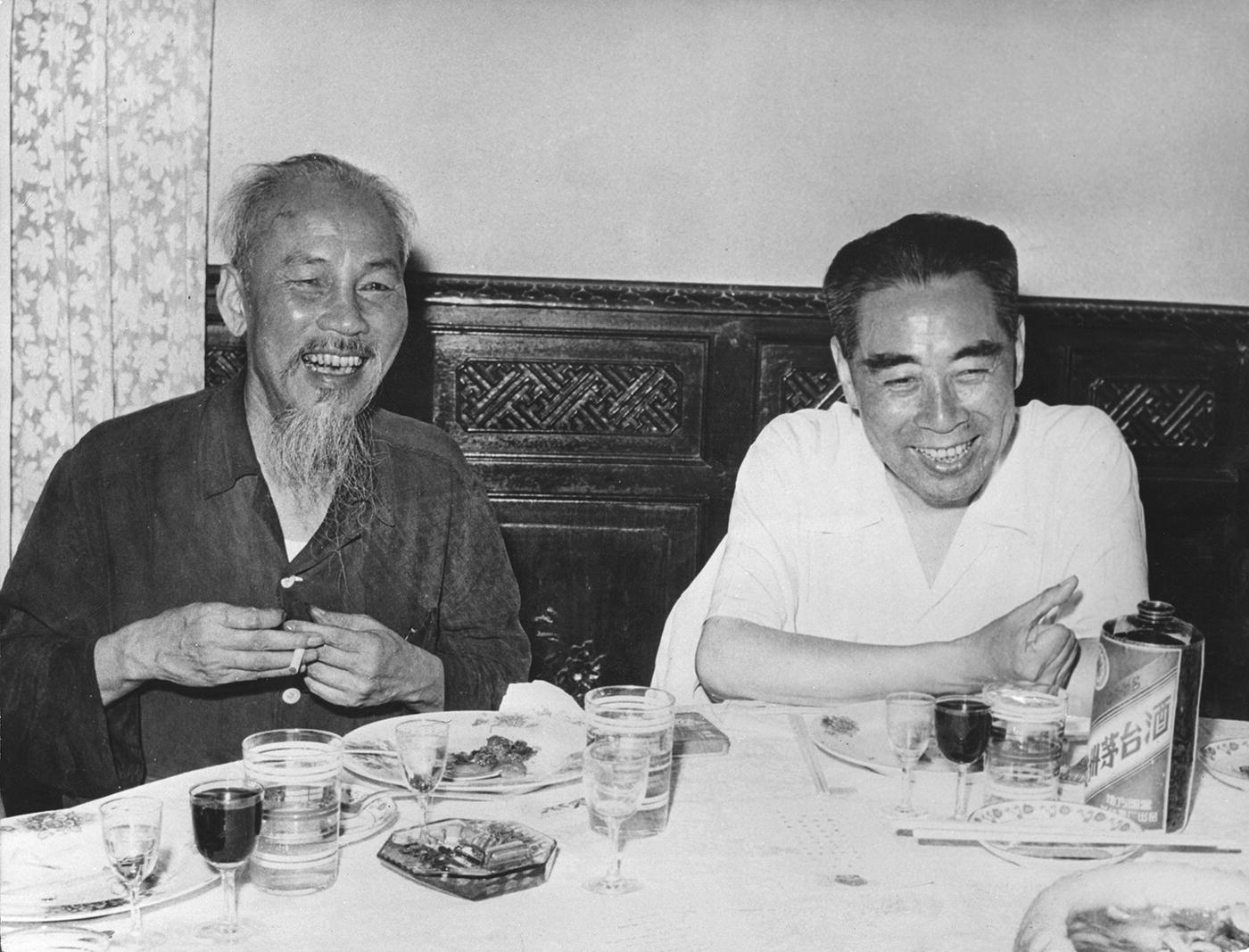

Viet Nam’s democratic springtime was the least developed of any. While Saigon had a robust pattern of plural politics since the 1930s, there was no such tradition in the north. The clandestine habit of communist cells to judge “enemies” and dispose of them covertly militated against judicial autonomy or political give and take from the beginning. Yet the communists’ minority position, and their need for both internal and external allies in the overarching goals of independence and unity, had created some tolerance of diversity. Only in 1949 did the communist victory in China, and western support for the Bao Dai government, convince Ho Chi Minh to align clearly with the Soviet bloc. Ho traveled to Beijing and Moscow in January 1950, learned that Stalin had agreed to Chinese leadership of the Asian revolutions, and negotiated the terms on which China would assist the DRV to defeat France. The price included acceptance of the Chinese line on the importance of absolute communist domination of government and army, and of an aggressive policy of land reform designed to destroy the landlord class (Figure 17.3). The Indochinese Communist Party, which had officially dissolved itself in 1945, was formally re-established as the Viet Nam Workers’ Party in 1951, and a campaign of terror against landlords began in 1953. Although the numbers executed in the years 1953–6 are highly controversial (from 8,000 to 500,000 have been estimated by opposite sides of the spectrum), it was certainly enough to persuade wealthy farmers who could do so to flee to the south in 1954.

Figure 17.3 Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai visits North Viet Nam President Ho Chi Minh in Hanoi, 1960. Zhou had played a key role in the Geneva peace talks of 1954, dividing Viet Nam at the 17th parallel.

Source: Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

During a moment of openness in late 1956, the Party conceded that “grave mistakes” had been committed during the agrarian reform. Truong Chinh, principal author of this “leftist deviation” was publicly demoted. In apparent emulation of Mao’s “hundred flowers movement,” following Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin, Hanoi intellectuals were at the same time permitted to publish a few issues of two critical journals, “Literary Selections” and “Humanities,” pleading for freedom of artistic expression. These were closed down at the end of 1956, a campaign of denunciation by harder-line Marxist-Leninists ensued, and in the first months of 1958 the critics were humiliated and forced to recant. Like the Confucian scholars who had provided embellishment and legitimacy for the pre-colonial monarchy, the role of intellectuals could only be to serve the state absolutely.

At the time of the triumph of communist parties in Saigon, Phnom Penh, and Vientiane in 1975, there was a diversity of intellectual tendencies in all three countries eager to see the end of war and US intervention, and hopeful for a new era of honesty and reconstruction. Theirs was the cruellest deception. The pro-communist southerners who had fought the southern regime were pushed aside as the northern army and Party took over the south. “Third force” neutralists, intellectuals, and artists were (again) imprisoned, their books banned. Truong Chinh, bouncing back as second in the Party hierarchy, inaugurated a program to eliminate all differences between north and south, and guided a new constitution for the united country declaring that “The Communist Party of Viet Nam … armed with Marxism-Leninism, is the only force leading state and society” (1979 Constitution, cited Jamieson 1993, 361). More than a million of South Viet Nam’s twenty million people were sent to a gulag of “re-education” prison camps, while about two million managed to flee the country, typically in small boats, over the next two decades.

The Pathet Lao depended heavily on Vietnamese communists for guidance, and followed their example of “re-education” camps where more than 10,000 of the old elite were imprisoned for ten to fifteen years. Flight across the Mekong to Thailand was easier than elsewhere, and about 10% of the total population of Laos, including most of the educated elite, took this option in the first five brutal years of Pathet Lao rule. Nevertheless, it could be said that although both Lao and Vietnamese communists followed the example of China in eliminating “class enemies,” neither suffered the Maoist extremes of political purges and massive sacrifice of their own peasant populations. The Khmer communist leader Pol Pot (1925–98), by contrast, exceeded Mao in his careless cruelty.

The Cambodian regime of 1975–8 was the work of Indochina’s weakest communist party, seething with racial resentment of its Vietnamese protectors as well as of the aristocratic or non-Khmer elites of Cambodia. Its primitive version of Maoist class war was to empty the cities, which it lacked the sophistication to control, and to eliminate not only those with privilege and property but also those with skills, education, or entrepreneurship. The 65,000 Cambodian Buddhist monks, who had for centuries provided much of Cambodia’s social cohesion, were killed, disrobed, exiled, or pressured to abandon the monastery for survival. While perhaps 100,000 of the Cambodian elite were deliberately killed during this short period, many times that number, a fifth to a quarter of the total population of eight million, died through brutality, starvation, disease, and neglect. Another quarter managed to flee as refugees. This was the most catastrophic of the communist utopian experiments in Asia.