FREDDY STARTED TALKING ABOUT Valentines’s Day at least two weeks before it arrived. “You’ll need a new dress,” he had announced. “Something special, something fancy.”

“Like what?’ I was amused.

“Ohhh—silk!” he cried. “Or lace. Or something.”

“Can it be black?” I asked, for that one black dress, off the shoulder yet suitable for concerts, still comprised my entire dress-up wardrobe, and I had no money to buy another.

Freddy considered this. “I guess. But we’re going to a dinner dance at a really fancy place,” he blurted out finally.

“The Grove Park?”

Freddy grinned triumphantly. “Not the Grove Park!” he said. “Anybody might see us at the Grove Park! Besides, this is Valentine’s Day. I want to take you someplace else, someplace glamorous, someplace you’ve never been before. We’ll need to leave here by three o’clock so we’ll have plenty of time to explore before dinner. It’s a four-course dinner,” he added, “so don’t eat any lunch that afternoon. We want to get our money’s worth.”

I had to smile at this typical remark, so Midwestern, so, well, Freddy-ish. Still, I couldn’t even imagine how much this evening must be costing him. “You’re really not going to tell me where we’re going, then?”

“Nope.” He shook his head.

“Good,” I said, for I do love surprises, if they are good ones, and I had had precious few good ones over the years. Also I loved it that Freddy had gone to so much trouble. But what in the world would I wear?

Sworn to secrecy, my chums came to the rescue. Ruth snuck out an armful of cocktail dresses from the exclusive downtown shop where she worked, then tossed them out on the bed, a rainbow of colors, as Amanda and Myra crowded into my room to look, too.

“I like the pink,” Amanda said immediately, holding up a ruffly chiffon dress that looked like a valentine itself.

I knew I’d feel silly in it, but I held my tongue.

“No, no, the blue—it looks more like Evalina,” pronounced Myra, choosing a three-quarter-length royal blue sheath with a jeweled V neckline and a matching cape. “See, it’s sort of demure, but really sophisticated.”

But I’m not, I was thinking hopelessly, I’m not sophisticated at all, when suddenly Jinx blew into the room and grabbed up a silver lame gown with a low, scooped neck and a swirly circular skirt. She held the dress up to herself, posing dramatically before the mirror, then started dancing with it, one arm out-thrust as if she led an imaginary partner up and down the hall. Jinx looked like such a waif—a little outcast, a tramp—yet every move she made had style, you had to hand it to her.

“But what about this one?” Ruth held up a dress with a white silk top and a layered black chiffon skirt. “Black and white is in, honey. It’s the cat’s meow.”

“Nope.” I smiled at everybody. “I’m going to choose—” I paused dramatically, then grabbed the silver dress from Jinx as she glided back into the room. “Ooooh, goody!” she squealed.

“Really?” Myra looked aghast. “You’d really wear something like that?”

“Absolutely,” I announced, as surprised at myself as they were, and wondering whether I’d actually have the nerve to do it.

BUT FREDDY’S REACTION was worth the risk, seeing his eyes grow round as plates behind his glasses when he came to pick me up that Saturday afternoon. “Say, honey, you look swell! Just gorgeous—like a real movie star.” I imagined my chums all laughing behind their closed doors. Of course I had to cover up my fancy dress with the old loden coat when we left, but nothing could spoil that initial effect.

Luckily there’d been a bit of a thaw during the past two days, so the road was clear as we drove down our mountain and headed east, out of town, which surprised me. “How far away is this?” I asked, and he said, “Fifteen miles,” so I put my sunglasses on and settled back to enjoy the view of snowy peaks shining in the sun. “Now you really look like a movie star,” Freddy said. I felt like one, too.

Big heaps of old snow had been pushed to the edge of the road all along, forming a wall of gray ice that would not melt until spring. But the highway was okay as we drove down past Black Mountain and headed off onto a secondary route. Freddy was holding my hand across the seat. “Now can you guess?” he asked.

I shook my head, still wondering a half hour later as the road began to climb, turning first tortuous and then downright scary. Freddy had to put both hands on the steering wheel. We crept along.

“Chimney Rock.” I read the sign aloud. “Is that where we’re going?”

Freddy shook his head no, still pleased with himself.

At length our road entered a dark forest that opened suddenly upon a large lake glistening in the sunshine. “Oh, my goodness!” I was completely surprised.

“Lake Lure,” Freddy announced as if he had invented it. Then I remembered hearing the nurses mention this place where they sometimes came on picnics and dates. Past shuttered lodges and summer houses we drove around the edge of the lake until we came to the big white hotel that we could see shimmering across the water like a mirage, its arched balconies and terraces extending down to the water’s edge. LAKE LURE INN 1927, announced the script emblazoned high up on its arched stucco façade—the height of elegance. This time, Freddy relinquished his station wagon to a valet without fear that he’d never see it again, and we had time for a walk along the balustrade at the lake’s edge. A cold brisk wind blew off the water and destroyed Brenda Ray’s attempt to style my fly-away hair.

“But this is just lovely,” I said. “It looks so much like Switzerland.”

“Does it now?” Freddy smiled happily as we walked along. He was a big, hard-working, good-hearted boy, really, easy-going and easily pleased. “A girl could do a lot worse now, mark my words, lassie!” Mrs. Hodges seemed to be saying in my head. The cold, clean air filled my whole body, swelling my heart. We held hands like children, walking along, though I was glad we did not go too far, as I could not afford to ruin Ruth’s sling-back silver slippers. I knew I could never replace them.

We stood on a promontory looking back at the Moroccan-style hotel beginning to bustle with activity now, arriving vehicles and people—Valentine’s Day sweethearts like ourselves. The water winked in the sun; the white mountain shone like a silver dome. Maybe I could really do this, really be “Freddy’s girl.” In a few months’ time I would no longer be a part-time patient but an official staff member, Phoebe’s assistant, Dr. Schwartz had confided.

“Okay, let’s start back,” he said, checking his watch. “We don’t want to miss a thing.”

Oh, how I loved him for that remark! I squeezed his hand.

WE WERE GIVEN pink champagne cocktails in long-stemmed glasses in the elegant lobby, which I found disconcerting due to its mirrored walls: who was that girl in the silver dress? I found myself sneaking glances at her, as if I were spying. We made conversation with a man from Greensboro who said he was “in the tobacco business,” and his beautiful wife; I wondered, but did not ask, if they knew Charles Winston. An ancient couple, brittle and frail as insects, told me that they had met on Valentines Day sixty years earlier. “May you be so fortunate,” the bent-over wife whispered into my ear.

When the French doors into the dining room were opened all at once, a collective gasp “Aaaah!” went up from the entire company. The semi-circular dining room had been specially decorated with pink linen, candles already glowing, and a long-stemmed rose on every table. We were given a choice location right in front of one of the huge windows facing the water. Though the sun was actually setting behind us, the surface of the entire lake turned red as we ate our lobster bisque and raw oysters, which Freddy politely declined, watching me down mine in amazement. “Chicken duxelles” were followed by “steamship” rounds of roast beef. Freddy ate his and mine, too, for I was overwhelmed by that point, though tickled to note that my date was getting his money’s worth. Dancing began as the orchestra played a medley of popular love songs: “I’ve Got My Love to Keep Me Warm,” “People Will Say We’re in Love,” “Embraceable You.”

“It’s funny how many songs are love songs.” I said.

“I wouldn’t know about that,” Freddy said, “but I can name every bone in the human body, all two hundred and six of them. Come on, now!” he pulled me awkwardly to my feet, and I realized he must be a little drunk. “Let’s get those tibias and fibulas moving!” First came a slow dance, “In the Still of the Night,” on which I did fairly well, but became alarmed when it was followed by the livelier tune “I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter.” Freddy twirled me around then suddenly relinquished me on this one, apparently expecting me to improvise some steps on my own, which he seemed to be doing. I grabbed his hand, hard, and pulled him back to me. “Never do that again,” I said.

“Why not?” he was grinning. “Give you a chance to shine.”

“No. Please. I love to be led. I’m an accompanist, remember?”

“You are many things, Evalina,” Freddy said, suddenly serious, into my ear, into my hair, which was all grown out now. “It may take me a lifetime to find them all out.” He led me around the polished floor that was thinning out now as couples sat down to the selection of fancy desserts on each table. More champagne arrived. Freddy really was a bit tipsy, overturning his first glass of it. Our unobtrusive waiter brought him another flute of champagne and another pink linen napkin, intricately folded—as they all were—into the shape of a swan. Little swan. Joey Nero rose before my eyes, smiling and swarthy, filled with so much dangerous life.

“To you, Evalina!” Freddy raised his glass.

“No, to you. No one has ever been so nice to me,” I said honestly.

He turned redder than ever.

I tipped his glass with mine, the crystal ringing. We drank.

“Let’s get a room,” I said.

Freddy stood right up and flung his napkin on the floor. We left our desserts untouched upon the table.

LATER I REALIZED that I should not have been surprised to learn that Freddy, at thirty three, was still a virgin. He had worked so hard to put himself through medical school that he’d had no time for girls. And he was so kind by nature; of course he would have wanted to take care of girls, rather than taking advantage of them. He would have thought of his sisters.

But I was not his sister.

“I’m your tour guide, remember?” I announced, surprising myself, and was further surprised by Freddy’s quick open ardor and my own rising response, there in a complicated antique four-poster bed in a room that would surely put this debt-ridden young doctor in the poorhouse . . . if it didn’t get him fired first. From now on, we would have to be very careful.

But we got our money’s worth, at any rate.

AT SOME POINT during that night, I woke up and went to the window to look out at the moon hanging huge and low now over the water. It made a path straight to me.

“Evalina?” Freddy got up and stumbled toward me.

“Look,” I said. “When I move, the moon moves, too. It comes toward you wherever you are, doesn’t it? Why is that? Here, Doctor, you try it.”

At first Freddy smiled indulgently, but then he tested out my theory, and it was true. “Oh Evalina,” he said. “Everything will come to you in time, honey. It will, I promise.”

THOUGH LIFE INSIDE the snow globe continued as before, our closed world defined by the wintry landscape and us captive within it, I grew more and more anxious as the February days passed swiftly one after another and March drew nigh. Why, oh why had I ever thought of the Mardi Gras performance? As if it were not enough to help plan the dance itself! Why had I ever brought Mrs. Fitzgerald into it?

For now she seemed more remote than ever, scribbling obsessively in the black notebook though reluctant to schedule any rehearsals. “Not yet, not yet,” she said, clutching the notebook to her chest. “There is a moment of completion, of fullest comprehension, which must arrive of its own accord, as if it were a messenger from another land, astride a horse.” She swept out the door and down the hall.

“Oh brother,” Phoebe Dean said to me. “If they’re going to do it, they’ve got to start practicing, right? Especially since they’re all mentals. It’ll take a while—remember Miss Mary?”

I certainly did. And I was already prepared, having obtained the sheet music of La Giaconda in its entirety through a mail-order company. I remembered now that Joey Nero had once sung the tenor role, Enzo Grimaldo, in Toronto. Yet this did not bother me at all but pleased me somehow, as if I were taking back that part of my life. And it is such fanciful, happy music—a joy to play. I felt that it would be good for the participants to dance to it—therapeutic, as Freddy would say. But who would the participants be? And when would we start?

Just when Phoebe was on the verge of canceling the performance, Mrs. Fitzgerald appeared in our music room dressed in a black, flowing sort of jersey shift, with black tights and the pink ballet slippers. “Now,” she said, opening the notebook.

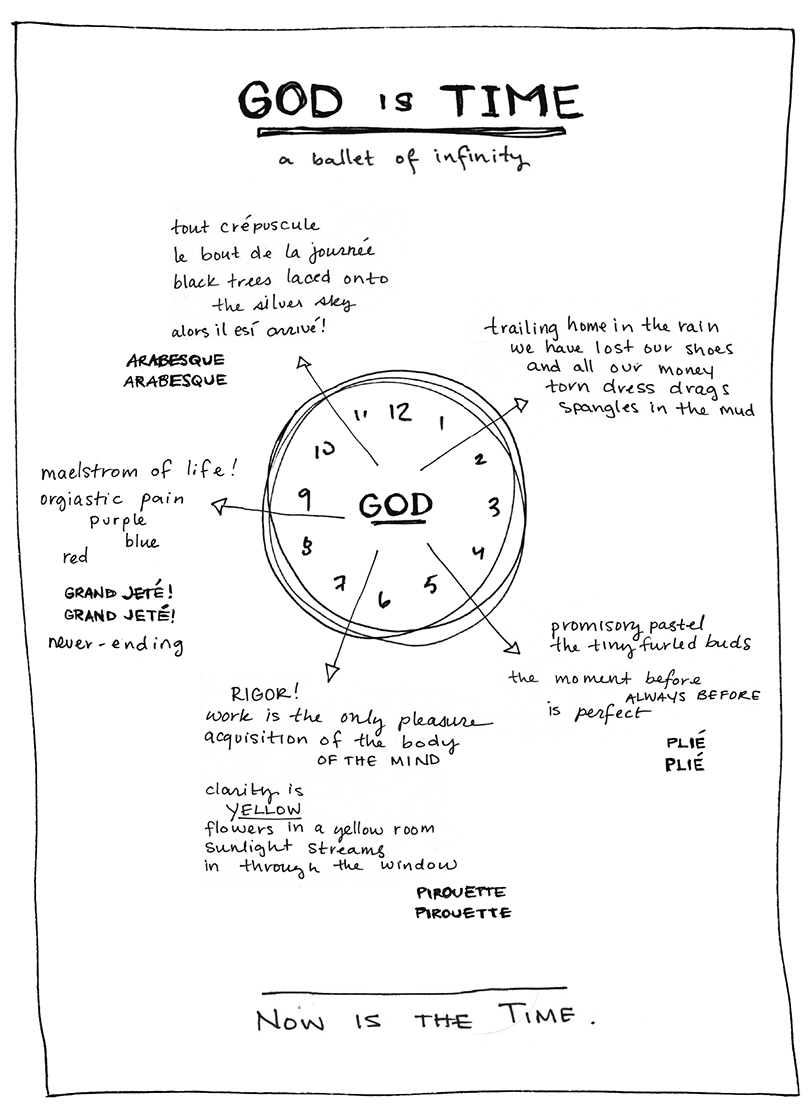

Phoebe and I were speechless as we stared at the diagram before us, which I shall attempt to reproduce here.

“I shall need eight dancers,” she said, “to comprise nine, along with myself, for nine is the powerful number, the number which is required for this dance. Three, you see—all multiples: Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. For He is life. Time is life, and He is time. Got it?”

We nodded stupidly.

“Excellent. We must begin immediately, this afternoon.” It was a transformation. Mrs. Fitzgerald looked calm yet purposeful, eyes snapping with an energy I had not seen since her return. Even her body looked different. Feet apart, weight evenly balanced on each, she stood lightly in the world now, ready for anything. Ready to dance.

“It’s too soon,” Phoebe told her. “We have to round up your dancers. How about day after tomorrow? That’ll be Saturday afternoon, so they can probably all come.”

“As you wish. But tell them they should come prepared to dance. Wear something comfortable.” With a dismissive wave, Mrs. Fitzgerald exited.

Phoebe and I looked at each other.

What had we done?

YET THE FIRST practice went surprisingly well, though only seven dancers showed up. “Don’t worry, we’ve got another coming next time,” promised Dr. Schwartz, who was present, too. I was very glad to have her and Phoebe there, and Karen Quinn as well, who had asked to perform, as she loved modern dance herself. “Though it has been years,” she confessed ruefully, large and very strong-looking in her green leotard and tights. Her feet were huge, bare, and very white. The others included my housemates, Myra, Amanda, Ruth, and Jinx, of course, the most enthusiastic of all—plus a shy new girl named Pauletta, and Mrs. Morris’s oldest daughter Nancy, a high school girl who had been taking ballet lessons in town for several years.

“First we shall limber up.” Mrs. Fitzgerald nodded to me and I began to play some little études as background music. “Just follow me.” She led them in a series of stretches, up, down, forward, side to side, in time to the music. It all looked surprisingly professional to me. But why not? Mrs. Fitzgerald had told me herself that she was once asked to join the San Carlo Ballet Company in Naples and offered a solo role in Aida, though she had refused, to her eternal regret. Down in the front row, I could see Dr. Schwartz begin to relax as well. Mrs. Fitzgerald sank gracefully to the floor, where the exercises continued, then ended with the girls all sitting cross-legged in a semicircle, Ruth and Myra breathing hard.

“This don’t look like any ballet dance I ever saw,” Jinx announced. “When do we get to jump up and leap through the air?”

Everybody laughed.

Mrs. Fitzgerald rose to stand before us all. “This will not be, strictly speaking, a ballet, my dears.” She was still composed. “It is, rather, an interpretive dance, a very famous dance, about the nature of time. You will form a circle, for you shall be Time itself—the minutes, the hours—and the music will tell the passing of the day from morning till night, or of a human lifetime, by extrapolation.”

“By what?” Jinx asked.

“Extension,” Mrs. Fitzgerald said. “Imagination. Use your imagination. I know you’ve got one. Play it for us, Evalina”—which I did, noting their immediate smiles. I knew it would make them happy.

“So. You will come in first and form a great circle, which will turn and turn . . .”

“Ecclesiastes,” Jinx said.

This remark stopped Mrs. Fitzgerald in her tracks. Then she smiled—that lovely and rare occurrence. “Exactly, my dear! Just exactly! Now let’s try it. Go offstage there, and come in like this, in a line, but see the step? Watch the step, you over there. Now you’re gliding, you’re gliding, now form the circle, now let’s go around—and around and around”—as I played.

“Now I want you to split up into groups of three. You girls over there—and you three in the center, come forward a bit, please—and the rest come over here, that’s right. Now we shall learn a little routine, a sequence of steps and movements. Evalina!” I played. “Again.” I played again as she performed the routine three times, then made a turn. But now Mrs. Fitzgerald seemed short of breath, and for the first time, I realized that I could see her age—forty-eight—which she must have been feeling, too, because she stopped suddenly and pointed to Jinx, saying, “Here, dear, why don’t you come up and lead, while I help the others individually?

Without a word, Jinx went forward and performed the steps flawlessly, as I played the spritely tune again and again while Mrs. Fitzgerald moved from group to group, instructing—reaching down to point Amanda’s toe, pulling Myra’s shoulders back so she would stand up straight, telling Ruth to be quiet. Jinx led them as if she’d been doing it for years, again and again, until Mrs. Fitzgerald clapped her hands three times and said, “Enough! Very, very good work, girls. Now you may go. Though I want you to practice, practice, practice on your own, the little routine which you have just learned. Practice before a mirror, if possible.” It would not be possible in most of the hospital. “If you get lost, ask that one,” pointing to Jinx, who nodded solemnly. “And I shall meet with you again on—” She looked out at her little audience.

“Monday at five o’clock,” Phoebe Dean called out. “One hour before supper. Here.”

The dancers came down off the stage and milled around, finding their belongings and putting on their coats; their chatter filled the auditorium. They had ceased to be patients; they could have been any young women, anywhere. I closed the piano, gathered up my music, and stepped off the stage to join the rest. Finally the girls began trooping up the aisle, followed by Mrs. Fitzgerald, who paused to address Phoebe and Dr. Schwartz. “So, what did you think of the rehearsal? Some promise here, I’d say, especially the little redhead.”

“Oh yes,” we all gushed, and that fleeting smile appeared on Mrs. Fitzgerald’s face again.

“You, Patricia,” she said, pointing at me now, “are fine. You are wasted upon us. And now, in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost . . .” she murmured as she continued up the aisle alone.

“Hey Zelda,” Jinx’s flat carrying voice came suddenly from the dark at the back of the auditorium, “you wanna smoke?”

And then they both were gone.

DR. SCHWARTZ AND I followed more slowly, Phoebe and Karen staying to straighten up and turn out the lights.

“You know what I wish?” I said, on impulse, turning to Dr. Schwartz. “I would give anything if Dixie could be here, if she could be in this dance, too. She would just love it, wouldn’t she?”—as Dixie had such a gift for fun. “I miss her so much. Have you heard from her at all? Because I haven’t, not a word. I don’t understand it. I keep thinking about her.”

Dr. Schwartz hesitated, looking down. Finally she put her hand on my arm. “It’s so strange that you would mention Dixie to me right now. You are very, very perceptive, Evalina—maybe you’re psychic or something.” She smiled to show me that she was just kidding. “Because the fact is that Dixie has been upstairs in the Central Building for some time now, but tomorrow she will be moving down to the second floor, and urged to participate in the life of the hospital again. So she might well be one of the ‘hours’ in this performance, if she wants to. In fact, we have saved the last spot for her, just in case. This was my own little secret. She can start on Monday. What do you think of that?”

I gave Dr. Schwartz a hug. “Oh, that’s wonderful,” I said—my first reaction. But of course I knew it wasn’t wonderful for Dixie. “What happened, though? She looked so happy when she left for Christmas. So did Frank—remember?”

“The short answer is, we don’t know what happened. And we may never know. All we can do is treat the illness, which is depression, as best we know how. And our knowledge is very limited, pitifully limited.”

“But you would think,” I pursued, “on the face of it, that she’s got everything—a husband who loves her, two children who love her—and she’s rich, too. She can go back to college like Richard said. She can do anything she wants or have anything she wants—except get that baby back, I guess. Do you think that’s the problem?”

“I think it may have been a factor, certainly, but most people get over such loss, or grief, or even traumas we can’t imagine. In fact most people will experience periods of depression in their lifetimes, and then they will get better eventually. There is the question of the body, which insists upon life—the organism itself wants to get better—the body always chooses life.”

“So you’re saying that Dixie—”

“I’m saying that the problem is that there’s no problem. No single cause. That question is not even relevant when we are dealing with clinical depression. This is what people don’t understand. Nobody understands it—especially not the relatives, or the people that love them, like Frank Calhoun. Everybody keeps thinking that there’s a reason, something that can be changed, something that can be fixed, and then the patient will be fixed, too. I’m saying that Dixie suffers from recurrent bouts of immobilizing clinical depression—a serious illness which we know virtually nothing about, except that there seems to be a genetic component. It does run in families. Someday medical science will learn much, much more about it. But personally I believe that some particular chemical is missing in the brain—rather like diabetes—and that once we figure out what it is, perhaps we can replace it. For now, all we can do is tranquilize them to take the edge off their pain, give them a more orderly routine for a bit, a sympathetic ear and a respite from their own troubling lives, and jumble up their brains in a way we do not really understand, which may be completely irresponsible, for all we know.” She sounded grim.

“Shock treatments,” I said.

“Yes, and Dixie’s got only two weeks to go on them, so there’s no reason she can’t participate in this dance if she wants to,” Dr. Schwartz emphasized. “We’ll see. Anyhow, she’s better.”

So was Mrs. Fitzgerald, clearly, outside sitting on the top step of Homewood’s stone portico, smoking a cigarette and laughing like crazy at something Jinx was telling her. What? I felt a bit jealous. I had known Mrs. Fitzgerald for years, and never had such rapport.

We went down the steps past them.

“You’d better get out of this cold,” Dr. Schwartz called back. “It’s time to go.”

“We will when we finish these smokes,” Jinx hollered out after us. “Bye now.” Though she was the youngest of us all, Jinx treated everybody—even the doctors—as equals.

Then the lights went off abruptly and all we could see of them were the fiery red dots of their cigarettes, glowing in the chilly dark.

FOR THE FIRST time, I thought I could feel spring in the air as I left Homewood at the end of the day. It had not snowed for almost a week, and the sun had shone all day long. Despite the continuing cold temperature, patches of grass were emerging everywhere, as rivulets of melting snow coursed down the slope, along the sidewalk. Rehearsal had gone well again, and I realized how much I enjoyed this kind of accompaniment, especially since Dixie had joined us. She struck me as very much her old self, friendly and laughing, interested in each person. Everyone seemed to light up while she was talking to them. No stranger, watching her in conversation, could ever have guessed that Dixie was a hospital patient in the middle of a course of shock treatments for clinical depression. Anyhow, I was overjoyed to have her back among us, as one of the “hours.” If I were not so grown up, I might have skipped down the hill, heading back toward Graystone—while keeping an eye out for Pan, of course, as always, though he was nowhere to be seen.

Instead, I rounded the corner and was surprised by an unfamiliar sight. A big old mud-splattered red truck pulling a silver hump-backed trailer with a long dent in its side, battered but shining in the sun, with yet another, smaller trailer hooked on behind, were parked right in front of our house. These vehicles looked as if they had escaped from the Dust Bowl, or from some Western movie set.

“Evalina?” Suddenly the passenger side door of the truck burst open and here she came running up the sidewalk, Ella Jean in a long leather coat with her black hair swinging below her shoulders, high-heeled cowboy boots slipping on the melting ice. She grabbed me up in a tight fierce hug.

“I can’t believe it,” I said, when I could speak. “Flossie told me you’re a star, and now you even look like one!”

“Flossie—Lord!” Ella Jean rolled her eyes and gave me her jack-o’-lantern grin. “Flossie is crazy as a coot, taking after Mama if you ask me. Still yet, she’s the one that told us you was back up here again, or I never would of knowed it. Told us where you was living, too. Lord, we’ve been about to freeze out here, waiting on you to get back from wherever you been keeping yourself all day.”

Who was us? I looked over her shoulder to see a big, gangly boy wearing a cowboy hat jump out of the driver’s seat, stamping out a cigarette and grinning from ear to ear. He came forward to greet me. “Bucky Pardoe,” he said, “pleased to meetcha.” His name made me laugh because he had the biggest, whitest buck teeth you can possibly imagine, along with straight yellow hair that stuck out from under his cowboy hat like straw. Though Bucky Pardoe was the opposite of handsome, his sky blue eyes were sharp, and I could tell instantly how smart he was. He had a sort of “go get ’em” style.

“I’m Evalina.” I stuck out my gloved hand.

“I know it, honey. I know all about you. That’s why we’re here. “

I looked at Ella Jean.

“Come on along with us,” she said, “and we’ll tell you. Just throw that book bag up on the porch and come on.”

“But don’t you even want to come in and see where I live?” I asked.

“Hell no, we don’t, we want you to come out.” She laughed. “We’ve been driving all night, we’re plumb wore out and now we’re starving to death. We’re going over to Fat Daddy’s and eat us some barbecue. I been telling Bucky how good it is. So you come on with us. You know you want some barbecue.”

I did not hesitate, sticking my bag inside the door without even telling anybody at Graystone where I was going. I ran back down the steps to the truck where Ella Jean had already taken her seat.

“Wake up, Jesse,” Bucky hollered as he opened the door on the driver’s side, and to my immense surprise, yet another man sat up in the smaller backseat and blinked at me through his long black hair.

“This here is Evalina,” Bucky said.

“That I was telling you about,” Ella Jean added. “The Cajun girl.”

“I’m not Cajun.” I turned to look at her in surprise.

“Well, I’m not really Cherokee either.” Ella Jean was laughing.

“Honey, in this business everybody has got to be somebody.” Bucky helped me up into the cab and handed me over to Jesse with gentlemanly finesse.

“How do,” Jesse said, taking my hand as if it were something precious. He had fine, thin hands with long fingers, hands that looked as if they had never done one day’s manual labor in his life. In fact, Jesse’s features were aristocratic, too—prominent nose and chin, long thin nose and heavy dark brows. “You sure do mean a lot to that one,” he nodded toward Ella Jean up in the front seat, “and she sure does mean a lot to us. It is a privilege to meet you.”

Most people picked up off the street in front of a mental institution do not receive such treatment. I smiled and settled back on the sheep’s-wool rug that covered the cracked leather seat as we drove down the mountain into town. The floor of the cab was crammed with boxes, boots, bottles, parcels, and sacks of every sort.

“Are you from the South, too?” I asked him. Somehow I didn’t think so.

“Very acute,” Jesse said, smiling at me. His eyes were a sort of dark violet color, with shadows around them. “No, I grew up in a number of different places around the world. My father was based in Washington. Then I went to school in Boston.”

“Where in Boston?”

“Harvard University,” he said. “Believe it or not that’s where I got interested in music, this kind of music. I came to the mountains to collect it, and started playing myself, and just never left. Never went back up there.”

“What did your family have to say about that?”

“This is my family now,” Jesse said, looking out the window.

We were pulling into the parking lot of Fat Daddy’s Bar-B-Q, where Ella Jean had taken me years before. Bucky finally found a space along the fence that would accommodate us. The ramshackle restaurant meandered along a hilltop north of town, with a giant wooden pig out front and smoke rising from the long cookers out back. Not a single thing had changed, that I could see—not the heavy wooden booths with the red cushions and red-checked linoleum tablecloths, or the wooden floor with sawdust on it, or the neon beer signs along the mirrored bar. The raised dance floor, empty now, shone behind a brass railing. Autographed pictures of country music stars covered the walls. “See, looky here.” Ella Jean pulled Jesse over, pointing at a skinny, grinning Jimmie Rodgers, the “Singing Brakeman.” “He used to live right here in Asheville,” she said. A photograph of Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys hung next to Uncle Dave Macon, the “Dixie Dewdrop,” in his double-breasted waistcoat, high wing collar, black felt hat and bright red tie. I guess it was true what Bucky had said, that everybody had to be somebody in country music.

“Can I start you off with some beer, hon?” The waitress wore a short red dress and a white ruffled apron, her plump breasts peeking over the top. Her ponytail swung side to side as she sashayed off to get the pitcher of beer Bucky ordered, along with a Coca-Cola for me and a “couple of shots” for Jesse, which turned out to be little glasses filled with—what? “Bourbon,” Jesse told me, downing one while sipping his beer more slowly. Ella Jean had ordered pork barbecue plates for everybody, along with slaw and rolls and hushpuppies and five or six vegetables and sides.

A silence descended as they all chowed down. “Appetite must be catching,” I remarked, eating ravenously myself. “I told you, didn’t I?” Ella Jean said, sitting back. “Lord that corn pudding was good. My Aunt Roe used to make corn pudding.” Before I could have imagined it, all the plates were empty. Bucky got up and played the jukebox: Bob Wills’s “San Antonio Rose,” Ernest Tubb’s “Walking the Floor Over You,” which even I knew was very popular, and some Roy Acuff. I finished my Coca-Cola and started drinking beer myself. It tasted pretty good, too. Almost empty when we came in, the restaurant was filling up now with big solid mountain families, couples out on the town, groups of both men and women. The waitresses swished back and forth with platters of food. The noise level rose. Bucky ordered another pitcher of beer and a pan of banana pudding which I was sure I could not eat a single bite of. It was gone within minutes.

I felt like I was in another world, a secret world filled with delicious food and wonderful smells and vibrant colors and catchy music that existed deep inside the Asheville I knew. I felt like Alice, fallen down another rabbit hole.

“Thank you so much for bringing me here,” I told them.

“Oh, we’ve got an ulterior motive,” Jesse said.

“What does that mean?” asked Ella Jean.

“It means you’re up to something.” I smiled at her and she smiled back.

This was Bucky’s cue. He leaned forward, blue eyes bright as buttons. “You got it, Sugar,” he said. “You know Ella Jean and me have been together ever since we met up with each other two years ago on a National Barn dance show out in Tulsa, Oklahoma.”

“Love at first sight,” Ella Jean said.

“Joined at the hip,” Bucky said.

“Where’d you get him, then?” I pointed to Jesse, who grinned.

“San Antonio. I’m a yodeling fool,” he said. “Just wait till you hear me.”

“So now we’re the ‘Kissin’ Cousins,’ ” Bucky announced, “and we’re headed over to Kentucky where we’ve got a great job waiting on us at John Lair’s Renfro Valley Show in Mount Vernon, about sixty miles from Lexington.”

“John Lair knows more about folk music than anybody in America,” Jesse put in.

“ ’Cept maybe you,” added Bucky, chewing on a toothpick. I could see why Ella Jean loved him—he exuded good will and confidence. Son of a piano man, he’d grown up in southwest Virginia, playing every instrument there was.

“But we’ve got one big problem,” Bucky went on. “We’re doing the show this coming Saturday night and we need us a keyboard player. Bad.”

It was already Thursday.

“What happened to the keyboard player you had?” I asked.

“Pregnant. We just got done delivering her back home to Danville, Virginia, where her mama wasn’t none too happy to see her.”

I looked from Bucky to Jesse, who held up both hands. “Not me,” he said. “Act of God.”

“I see.” Now I looked at Ella Jean. “Whatever makes you think I could actually do that? Play keyboards for a country band, I mean? I went to Peabody,” I said to Jesse, who nodded.

But Ella Jean said, “Evalina can play anything. All she has to do is hear it one time.” I knew she was right. I could do it. And then I could sleep in a truck and eat in places like this one, with people like these, and travel all over the country, playing music every night. My palm itched furiously as I thought about it.

“Come on and go,” Ella Jean said. “You know you want to.”

“I do,” I said. “But I can’t. I just can’t. I’ve got some things here to take care of. Some things to finish up right now.”

“You’re going to regret it,” Jesse said, looking at me. I thought of Matilda Bloom telling me I’d better grab that brass ring, that it ain’t gonna come around again. And I had a feeling this might be my last chance.

But I also knew I had no choice. I couldn’t leave them now, my people, my kind.

“Cousins, I thank you,” I said, standing up. “Thanks for a wonderful, wonderful evening. But I guess you’d better take me on back now.”

Which they did, though I still dream of what might have happened had I gone with them, all the highways we would have traveled, and all the things I would have seen. Jesse became famous, of course, while Bucky and Ella Jean got married and stayed on in Renfro Valley and had five children. I own several of Jesse’s albums, and I have saved that copy of Life magazine with his picture on the front of it.

“Where you been?” Jinx slit her green eyes at me as I slipped quietly back into Graystone.

“Just out with some old friends.” I hoisted my book bag.

“Who?”

I didn’t answer, but followed her over to the window as she peered out between the venetian blinds at the messy, empty street.

BY REHEARSAL TIME the next afternoon, I could hardly believe that Ella Jean’s visit had really happened—it seemed like a dream, disappearing more and more throughout the day. I didn’t mention it to anyone.

This was an important rehearsal. Satisfied that the hours had finally “got” the first part of the dance, which was quick, fanciful, and even humorous—as keyed by the spritely music—now Mrs. Fitzgerald was leading them into the slower middle section, where the mood turns to doubt. The movements she showed them were somber and slower; I played softly. A beseeching tone crept into the music as each group searched a different section of the stage, peeping and bending, then extending their arms in an attitude of loss.

Ruth stopped right in the middle of it. “So what’s going on already?” she said in her most aggravating voice. “I hate this! The first part was fun, but this is making me nervous. We don’t have to do this. I’m not going to do it if it makes me nervous, if it’s not fun.”

“Me neither,” Amanda said. “This is stupid. It’s depressing.”

“Y’all need to shut up,” Jinx spoke flatly. “You just shut up and do it. Or maybe Dr. Schwartz needs to give everybody another pill.” Some of the hours laughed, but Pauletta, the new girl, covered her face with her hands and started to cry. Mrs. Morris’s daughter looked confused.

“Now, girls.” Mrs. Fitzgerald appeared entirely unperturbed as she turned gracefully to address them. “I am impressed by your sensitivity to the music and your understanding of this dance. Yes, the mood has changed. We are entering the middle phase of life where one often gets lost in a dark wood. We must go through the darkness to find the light. Of course you would understand this, you of all people. For this is art, and you are born artists, ballerinas every one of you! And now you must become frantic, running in a circle, just so—” She nodded to me, and I played spiky arpeggios while she led them to form the great circular clock again. Miraculously, not a one had dropped out. “And now the clock strikes six.” Again she nodded to me as I struck the slow, sonorous minor chords. “And now you all must run off the stage—you four to stage right, you four to stage left. Yes, run off! Quickly! Run, run, run! That’s it.”

The hours stood in the wings, panting hard, exhausted though proud of themselves.

“We shall leave the stage bare for four full measures before the grand finale, which will be fun, I assure you! And you shall have earned it, you see? For this is art—no light without the darkness!”

“So what’s the grand finale?” Ruth asked, her trademark sarcasm gone for once.

Mrs. Fitzgerald stood tall and gave them her most radiant smile. “It is—the cancan!” she promised. “Next time! Now once more, back into those dark woods again, girls, before we leave . . .”

I began to play the slow middle movement as they scattered obediently into their tentative search across the stage with Mrs. Fitzgerald watching them, nodding, pleased.

“Hellfire! That ain’t dancing, that’s just running around. Anybody can do that, that’s got legs! I can dance better’n that with my eyes closed!” A piercing country voice cut into the ballet.

Mrs. Fitzgerald walked forward to center stage and held up her hand like a traffic cop, stopping the dancers, and I ceased playing, too, which was a good thing as my hand had begun to itch furiously. “Who is that? Who is there?” Shielding her eyes with one hand, Mrs. Fitzgerald pointed imperiously past Dr. Schwartz and Phoebe Dean, sitting in the front row. They turned around in their seats to look up the center aisle, too.

“No spectators, please. This is a closed rehearsal.” Mrs. Fitzgerald spoke firmly.

“Well, I can dance, too.” The voice rang out in the dark auditorium. “I can dance better’n any of y’all. Ask anybody. And I have been on the stage, too, you might say, over in Knoxville, Tennessee, which none of these others has, I can tell you for a fact. Not a one of them. I’m the best dancer that ever was, and I’d be glad to help y’all out, iffen you was to ask me.”

“Oh, thank you so much for volunteering,” Dr. Schwartz began quickly, “but actually—”

“I ain’t asking you, ma’am. I’m asking her, that one up there on the stage,” came the voice.

“Now, Flossie.” I stood up at my piano but could see only her yellow hair in the dim recesses of the auditorium. “Of course you’re a great dancer, but you must have misunderstood. This program is just for—”

“You shut up! You just shut up, Miss Priss, I know all about you. All about you, don’t think I don’t—haven’t even got enough sense to get on the bus!”

“That’s enough.” Mrs. Fitzgerald had come forward to the footlights now, hands on her hips, wearing her Cherokee face. She sounded very definite and even mean. “You—must—go—now!” She spaced out the words for emphasis. “Auditions are closed.”

“They wasn’t no auditions. This ain’t nothing but a exercise for crazy people—”

Karen Quinn moved forward to stand on one side of Mrs. Fitzgerald, with Jinx already on the other.

But Mrs. Fitzgerald didn’t need any help. “Go now!” She looked terrifying, like one of her own paintings.

“Bitch!” we heard, followed by the slamming, echoing door. Some of the hours giggled.

“My goodness,” Mrs. Fitzgerald said mildly. “Now, girls, one more time—”

I couldn’t believe they’d do it, but I started playing, and the hours started dancing again. Suddenly it was all over—both the unsettling incident and Mrs. Fitzgerald’s change in mood. She was pleasant and professional as she told them good-bye and let them go, chattering and excited, back into their own afternoons, Flossie’s outburst already forgotten.

“This is not the first time I have wondered about that kitchen girl,” Dr. Schwartz told the rest of us, “though of course one rarely sees her . . . but there’s something, something . . .”

“There’s something wrong with her,” Phoebe said flatly.

“Perhaps I should speak to Dr. Bennett about her,” Dr Schwartz mused, putting on her coat.

“Don’t,” I said, “She comes from a very poor family. I know she needs the job—”

They both looked at me.

“I knew her sister, Ella Jean, when I was here before.”

“You are always surprising me, Evalina,” Dr. Schwartz said thoughtfully as we all left together.

LATER, AS PHOEBE Dean and I entered the music room together, she remarked, “You know, I think I do remember the other one, the sister—isn’t she that girl who used to come in and play music with you?”

“That’s her,” I said. “Ella Jean Bascomb. Their mother worked in the kitchen. Mrs. Carroll didn’t like for me to be friends with her.”

Phoebe snorted. “I can just imagine!”

Then she pointed at my piano, where a handful of purple and blue crocuses lay scattered across the keyboard.