KATRINA, UNLIKE ME, HAD a very stable and lucrative career working in the cardiology department of a major Memphis Catholic hospital. She started her profession while a college student working part-time doing EKG hookups. This worked its way into her doing treadmills, where heart patients put stress on their hearts while walking on a treadmill and then the heart is tested ultrasonically to see if the heart reacts abnormally to the stress. She was fascinated with the mechanics of the human heart and studied hard and diligently. She began training as an ultrasound technician which launched her into a much higher salary with greater prestige in the hospital hierarchy. Her job was the financial anchor during our entire marriage.

My jobs were much iffier propositions. Even before I had graduated from Memphis State University with a degree in Journalism my writing had been recognized and I had won some awards. I was quickly hired out of college by one of the city’s better advertising agencies and put to work as a P.R. writer with a nominal salary and virtually no training or help at all. Other than part-time college jobs I had no real experience in the corporate world and almost immediately discovered myself a very square peg in a very round hole. I never took to the cubicle life and found the typical 8 to 5 routine oppressive and life-diminishing. Looking back, I don’t think there is a single boss I ever liked. With my flinty attitude it is no wonder that despite appreciation for my writing talents, I was forever in hot water over one thing or another, sometimes just chickenshit demerits like lingering too long over coffee breaks and sometimes when I’d clearly crossed the lines of corporate etiquette. I blame myself.

My advertising work won awards, lots of them, but I wasn’t liked in the high offices due to my abrasive personality. Outside the office, people thought I was a friendly and affable fellow. Inside I was thorny and combative. The reason was simple enough; I hated what I was doing.

The longest and best job I had during this period of my life was as the copywriter for a major manufacturer of orthopedic and otology devices, Richards Medical Company. It paid well and I worked with a great group of talented creative people. I even liked my boss most of the time. I lasted there nearly seven years, a record, until I began teaching.

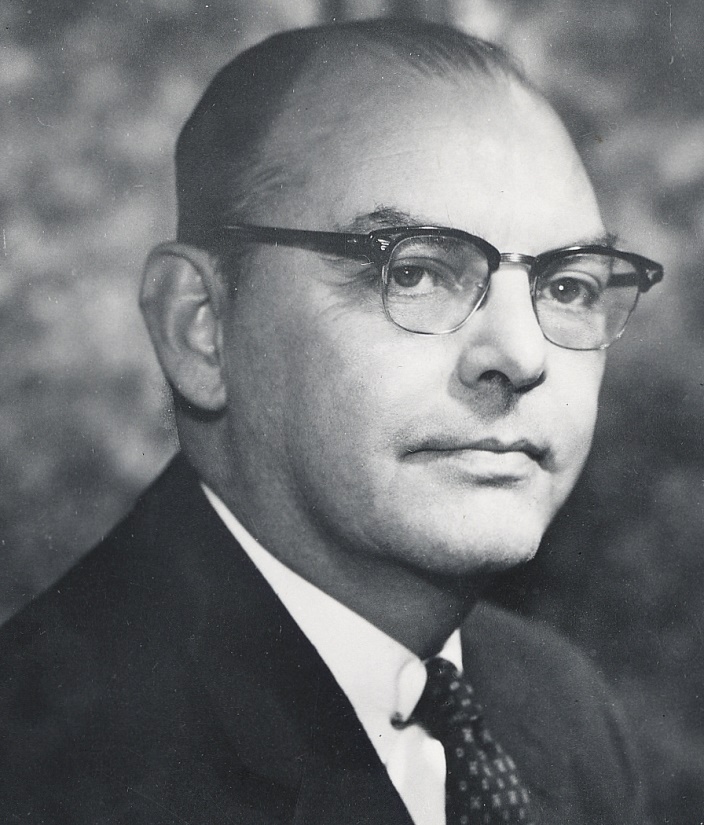

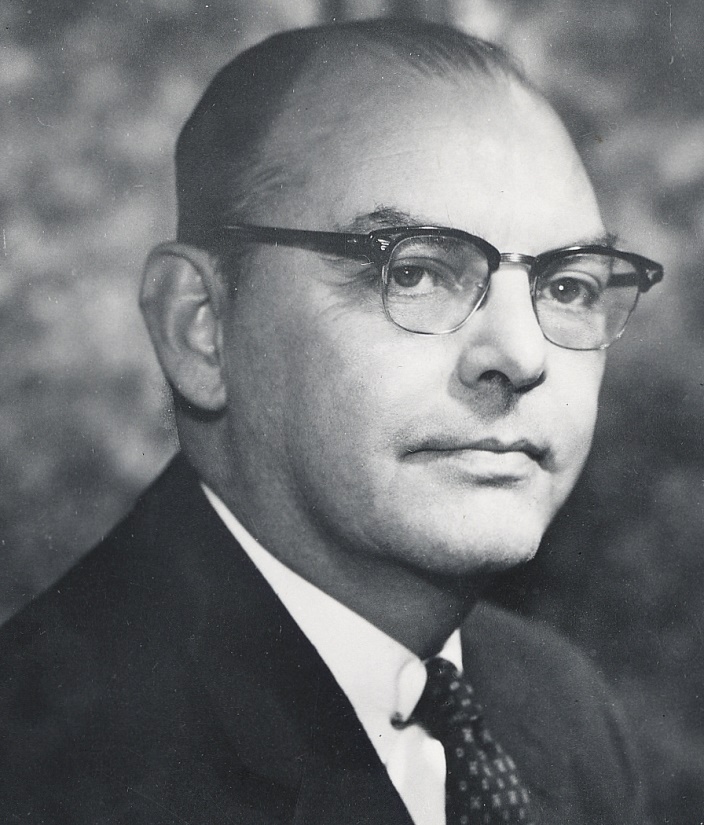

One of my favorite characters at Richards Medical Company was Dr. Hugh Smith, a retired super-surgeon who was hired as the medical consultant for the company. Dr. Smith was without question one of the ten greatest orthopedic (Dr. Smith made a point of spelling the word “orthopaedic”) surgeons of the 20th Century and even after retiring from surgery in 1982 was much in demand as a consultant all over the world. His official title at Richards Medical Company was chief medical officer. I was the chief copywriter for the company, a much lower position let me assure you, writing ads that appeared in orthopedic journals as well as surgical techniques that step-by-demanding-step told surgeons how to perform new surgeries.

Dr. Smith reviewed every word I wrote and often laid into it with a heavy red pen. On my bookshelf today rests a paperback copy of the indispensable writers’ reference book Elements of Style by Strunk and White signed by “the old weird orthopod, Hugh Smith.” I think he hoped his little gift would improve my writing.

Dr. Smith, in his retirement years, was known to take a drink or two, often before the socially acceptable hour of 5 p.m. One afternoon, Dr. Smith and I were waiting for a flight with a group of others from Richards Medical Company.

“What do you bet some big, fat nigger woman comes and sits right next to me on this plane?” Dr. Smith cackled into my ear at the airport that day, the tang of bourbon perfuming his breath.

Well, what does an underling say to that?

Dr. Smith was known for salty language and wasn’t exactly careful with his racial rhetoric either. So, was this man a racist? Based upon such alcohol-fueled utterances one could be forgiven for thinking so.

But like almost everything in Memphis involving race, not all was as simple as black and white. I can clearly remember a Christmas ceremony at Richards Medical when Dr. Smith, a concert level organist who often gave recitals on the city’s grand pipe organs, performed an organ duet with a black employee who was an organist for his church. The gospel style of the black church and Dr. Smith’s classical leanings meshed wonderfully. At the finish Dr. Smith gave a slight smile, a flourish of his hands on the keyboard as he hit the final notes, and there was a noticeable twinkle in his eye.

Dr. Smith was one of the founding surgeons of the world-renowned Campbell Clinic. He was an editor and writer for several editions of Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, which is the bible of orthopedics, a tome directly responsible for the healing of millions upon millions of broken bones. As Dr. Smith would tell me, a great deal of orthopedic learning was advanced by war, particularly World War II. Soldiers needing bone treatment were sent via train to Memphis and Kennedy Hospital, which proved to be a training ground for Campbell Clinic surgeons and their interns.

On September 26, 1937, when Dr. Smith was still an intern at Campbell Clinic and destined to become one of the greatest surgeons in his field, he had set off with a fishing buddy shortly after midnight, heading down the fabled Highway 61 into Mississippi, most likely wanting to get an early start on the fish biting at Tunica Lake. Around 2 a.m. he came upon a terrible automobile accident. A black man and woman had sideswiped a heavy truck that had pulled in front of them as it tried to re-enter the highway having been pulled over on the shoulder. The impact of the collision sheared off the woman’s arm below her elbow and had severely damaged her internal organs. According to an interview with Dr. Smith years later what he witnessed was “a traumatic amputation.” Dr. Smith was a take charge kind of man, a leader, a general among surgeons. Even as an intern he had undoubtedly treated thousands of African-Americans. I know this for fact because he regaled me with stories about treating black patients. And no, these weren’t racist stories. Just a doctor’s tales, and he had seen a lot.

At first, Dr. Smith did not know that the woman who was almost bled-out lying in the middle of Highway 61 was the blues diva Bessie Smith. Even though he was an avid fisherman who probably felt some irritation that his fishing recreation was going to be delayed, he nonetheless prepared and applied a tourniquet to Bessie Smith, trying to keep her from completely bleeding to death. His fishing buddy ran to get help from a nearby farmhouse. Dr. Smith began to clean his car out to make room to transport Bessie Smith and her driver to the nearest black hospital which was located not even half a mile from the white hospital, which everyone thereabouts knew did not accept black patients. That was a sad fact of life in 1937 in the heart of the Mississippi Delta.

Just as Dr. Smith threw some things by the side of the road to make room in his car for Bessie Smith, a car driven by two whites plowed into the back of his vehicle, slamming it into Bessie Smith’s car. Suddenly Dr. Smith had four people injured on the highway, not two. Ambulances arrived soon after. One of them, driven by a black man, took Bessie Smith directly to the nearby black hospital, the G.T. Thomas Afro-American Hospital, in Clarksdale. (The hospital was converted to a hotel, The Riverside, in 1944 and virtually every blues musician of note at one time or another stayed there. Today it is a major tourist attraction in the city.) Within a few hours after admission to the hospital Bessie Smith, the reigning blues queen of the 1920s whose fame had all but dissipated by 1937, was dead. She was to perform the next day in Darling, Mississippi and had left Memphis earlier that evening. Dr. Smith told an interviewer in 1938 and a Bessie Smith biographer decades later that there was virtually no chance of Bessie Smith surviving such a traumatic accident. I believe him.

Just as with blues legend Robert Johnson who I have written about, a whole myth has grown about Bessie Smith and her death on Highway 61. The most prominent of the tales is that Bessie Smith died because she was refused admission to the white hospital. It never happened. No one in 1937 would have wasted one minute trying to take her there. Especially with a black hospital practically right next door. Another of the conjectures is that Dr. Smith could have saved Bessie’s life but refused to touch her because she was black. Yet another has it that he didn’t want to get his car bloody by transporting her to the hospital. The facts are that Dr. Smith—the same man who whispered those shocking words in my ear—stepped up and did everything he could to save Bessie Smith and in the process had his Chevrolet automobile totaled and his holiday ruined.

With his own hands there is no question in my mind that Dr. Smith saved thousands of lives of whites, blacks, and numerous other races. His innovative and progressive orthopedic surgeries, not to mention instruments and implants he invented, plus his work on the all-important Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics, saved and healed millions. I have been treated for injuries at Campbell Clinic several times in my own life, since I was a teenager falling off a skateboard. Residents of Memphis consider it the best orthopedic hospital in the world. So do many others. Dr. Smith’s techniques very probably were used to heal me.

I never knew that Dr. Smith was the one who stopped that early morning on Highway 61 to tend to Bessie Smith. Had I known, I would have plied the doctor with endless questions, probably to his annoyance. He said some bad things, yes, made some very off-color remarks, certainly. Yet his actions showed that he was a man fully capable of putting those Jim Crow-era feelings in an interior jack-in-the-box that would spring open only when he was good and ready and felt you were the right audience. As the Good Book says, we are sinners all. Dr. Smith, in my estimation, was a great man, quite eccentric, quite brilliant, and if you were around him you never knew what he might say. That old weird orthopod; I’m glad to have known him and even with his dark flashes think he did the world a hell of a lot more good than evil. Rest in peace Hugh Smith.