Now that you’ve learned what goes into thinking up new games, let’s look at how these games go from ideas to actual games you can play. After all, there’s no fun in a game that stays in someone’s head or a designer’s notebook!

Dominion developer Dale Yu thinks of his job as being similar to that of a book editor. He takes what the designers submit and tries to make the best game possible, similar to the way editors take a manuscript from a writer and try to make it the best book possible.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

Why are game design and game development considered different parts of the game-making process?

marketing: communicating in different ways to make a business known.

product engineer: a person who designs and develops something that will be sold.

manufacturing: making large quantities of products in factories using machines.

distribution: the way a product is divided up or shipped out to stores.

Developers work out all of the kinks by playtesting and revising the game. One way developers do this is by trying to break the game. What?! Why would they want to break a game? Wouldn’t they want to make it better?

Trying to break a game actually does make it better. Developers push the game mechanics and rules to the limit, playtesting them over and over to make sure the game works well.

Game design and development are part of a loop.

Design documents are crucial for the process.

Look back at the image of the Design Process in Chapter 4. Designers come up with an idea, build a prototype, test it, make changes—and then repeat the process again and again until the game is just right.

Remember the design document started by the game designer? This document survives throughout the development process. It is a way for the development team to understand what the designer intended. The development team might include game developers, playtesters, writers, artists, managers, marketing people, and product engineers.

For managers and marketing people, the designer might simply write a short description of the game. For the rest of the team, though, the designer would describe the game mechanics, rules, components, and other aspects in great detail. This information will help the development team test, revise, and produce the game!

Let’s look at the different parts of game development—prototyping, playtesting, publishing (which includes manufacturing, distribution, and retail) and marketing.

DID YOU KNOW?

Many developers use common Magic: The Gathering cards to prototype games that use cards. Magic players tend to discard cards that are less valuable.

PROTOTYPING

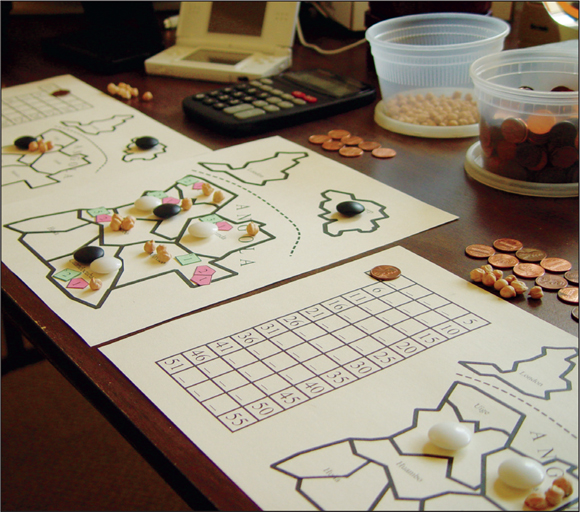

In the first step of the process, developers build a prototype of the game—maybe even several prototypes. A prototype is a simple version of the game that can be tested out. The prototype should include the game’s rules and components. It can be made of paper, cardboard, or even pieces of other games. For instance, a card game developer might make a prototype using paper printouts or labels pasted onto old playing cards. Dale Yu, for example, used plastic card sleeves in his Dominion prototype.

A developer might build several different prototypes, adjusting them as they’re tested.

Although game development shops sell components for prototyping, most developers collect their own supplies from other sources. You can make your own prototyping kit with some of these items:

•Old playing cards

•Card sleeves

•Labels (full page, name tag, and address)

•Paper of all colors and weights

•Dice

•Tokens and similar pieces from other games

•Plastics cubes and chips (from teacher supply stores)

•Bags and baggies (sandwich and snack size)

•Boxes

A paper prototype of a game called Diamond Trust of London, designed by Jason Rohrer

Tabletop Simulator

Developed by Berserk Games, Tabletop Simulator is a virtual game-testing program. Developers can use it to playtest tabletop games online by uploading their own artwork and then playtesting remotely.

You can take a look at Tabletop Simulator at this website, though to play the games requires purchasing the service.

You can take a look at Tabletop Simulator at this website, though to play the games requires purchasing the service.

![]() Berserk Tabletop Simulator

Berserk Tabletop Simulator

Playtesting a game

credit: Tikva Morowati (CC BY 2.0)

PLAYTESTING!

Playtesting is a crucial part of game development, one that new designers often skip. During this phase, people play the game over and over again using the prototype. Playtesting allows designers and developers to step back from their game and see its strengths and weaknesses through someone else’s eyes—someone who has never played the game before. To designers and developers, the elements and rules of a game may seem obvious because they’re so familiar with what they created. But to someone new to the game, those rules may not be at all obvious—and may even be confusing or not fun!

For example, the inventor of Pirate’s Cove, Paul Randles (1965–2003), playtested his first game hundreds of times. This helped him perfect the game and really understand how people played it.

packaging: the wrapper and all the parts of a container that holds a product.

investor: a person who gives a company money in exchange for future profits.

crowdfunding: a way of raising money for a project that involves many people each contributing a small amount.

Often, designers and developers will playtest the game themselves first—and make changes. Then, they’ll get players to test out the game. Sometimes, they even hire people to do this— does this sound like a dream job? Playtesters often get paid in game copies. Testing is usually done several times at different stages of game development. For example, developers might playtest before the rules are finalized just to see if the game mechanics are fun. Later playtests work out issues with game play and the rules. Some playtesting may even focus on how the packaging looks! Why do you think all these types of playtests are important?

What happens during a playtest? As a group plays the game, the development team watches them play and takes notes. Developers may also interview the players after each game. Based on what they learn, the designers will make changes to the game— and then playtest it again. Developers keep doing this until the game is fun and playable.

Self-publishing

Game developers can also produce a game by self-publishing—they publish the game themselves. This means they have to do all the work a game company might do! The designer needs to find funding, produce the artwork, get the game board and pieces manufactured, find distributors, and market the game. Self-publishing is basically like running your own business!

PUBLISHING

How does a game go from a prototype to a glossy box sitting on a store shelf? There are actually several routes. Some designers and developers may work for a game company, large or small. In that case, the company publishes and markets the game. A small company might need to raise money through investors to do this.

However, many designers work for themselves. They might design and develop a game and then pitch it to a game company. Remember Matt Leacock? He got his start licensing Pandemic to a game company. In either case, the game company takes care of manufacturing and distributing the game.

Manufacturing. After the developers have honed the game, the company sends it to its art department. There, graphic designers polish the artwork and writers edit the rules.

The art department also designs the packaging.

DID YOU KNOW?

Both self-publishers and small companies sometimes use crowdfunding sites such as Kickstarter to raise the funding for game projects.

Once the graphic design is finished, the game goes to the production people. They select the materials for the game board, pieces, and packaging. Production takes the computer files generated by the art department and has them printed.

Board games on display at a café

credit: Gary Sproul (CC BY 2.0)

consumer: a person who buys goods and services.

distributor: a company that buys a product from a manufacturer and sells and delivers it to a store.

wholesale: large quantities of an item bought at a cheaper price in order to resell at a higher price.

brick-and-mortar: a term that means a physical store.

What happens once the game starts rolling off the production line?

Distribution. A game company doesn’t usually sell directly to stores or consumers. Companies called distributors buy many copies of the game from the game company. Generally, these distributors pay wholesale prices or even below-wholesale prices. The distributor stocks the game in its warehouses, takes orders from stores, and then ships copies of the game to these stores.

Retail. Today, two kinds of brick-and-mortar stores generally sell tabletop games. Small hobby or game shops tend to stock hobby games, such as Magic: The Gathering, Dungeons & Dragons, and Warhammer. Big-box stores such as Walmart and Target tend to sell mass-market board games, such as Monopoly and Scrabble, as well as more popular hobby games, including Settlers of Catan and Pandemic. Online giants, such as Amazon and eBay, sell all kinds of board and card games.

Kickstarter

In the early 2000s, European-style games such as Carcassonne and Settlers of Catan created demand for more cool and interesting games. But developing them and getting them to market was hard—until Kickstarter came along. Founded in 2009, Kickstarter is a crowdfunding site for creative projects. It was originally developed to fund music and film projects, but game developers soon discovered it. They can post a polished game prototype and request interested gamers to fund the project. In 2017, the average successful tabletop game raised more than $65,000 on Kickstarter. This crowd-funding site has revolutionized tabletop games by making it possible for more game developers to create and publish their games.

In order to sell a game, designers and companies have to think about who is going to buy it. Former game designer Brian Tinsman divides the board game market into four categories: mass-market, hobby games, American specialty, and European.

Mass-market games are popular classic, family, and party games that are usually found on the shelves of big stores. These games include Monopoly, Scrabble, Taboo, Boggle, Cranium, and most kids’ games. You probably have some of these games at home.

Hobby games are more complex. Fans may play these games often and regularly buy new cards, figurines, and expansions for the game. Roleplaying, war gaming, and collectible card games fall into this category.

American specialty games are American games that aren’t mass-market or hobby games. These include strategy, sports, and mystery games. Apples to Apples is a popular example of an American specialty game. In this game, players take turns judging each other’s choices for inclusion in certain categories.

European games, as we discussed earlier, originate mostly from Germany. These games tend to be more strategic and thoughtful than mass-market games. Today, many non-European game designers and companies produce European-style games. Some popular European or European-style games include Settlers of Catan, Carcassonne, Ticket to Ride, Pandemic, and Puerto Rico.

Codenames

One of the best new party games of recent years is Czech Game Edition’s Codenames. Designer Vlaada Chvátil (1971– ) came up with the idea at a gaming event and even playtested it that day.

Codenames is a deceptively simple word-association game. Two teams of players give their team members one-word clues to help them uncover the codenames of their own secret agents. Vlaada believes the player experience is more important than the game’s theme or mechanics. Codenames forces players to use both their imagination to connect words together and their social skills to make sure their teammates can get the clue. Codenames won the Spiel des Jahres in 2016. Have you ever played it?

All of these different types of games are marketed to audiences through various types of media. These include television, magazine, newspaper, and online advertising.

Game companies spend quite a lot of money researching ways to get the word out about their games.

Can you think of any game advertisements you’ve seen lately? What were they like? Do you think they were convincing? Did you want to buy the game after watching?

One game designer compared developing a game to sculpting. When designing a game, he’d cram everything he could think of into that game. But, during development, particularly during playtesting, he trimmed away all the excess stuff to reveal a great game that works.

Gloomhaven is a success story no one could have predicted, least of all its designer, Isaac Childres. It’s a massive, cooperative fantasy board game that got its start on Kickstarter. In September 2015, Isaac took to Kickstarter to raise money to develop the game. His goal was to raise $70,000. People could pledge $79 in exchange for getting the game once it was produced.

Twenty-eight days later, nearly 5,000 people had backed the game and Isaac had raised nearly $400,000! He used the money to develop and produce Gloomhaven. A year later, he, along with game company Cephalofair Games, delivered the huge game to backers—it weighed 20 pounds! The game company also produced 2,000 additional copies for retail stores. Only there was a problem. Customers had pre-ordered 25,000 copies from retailers. They’d heard how good the game was and wanted copies. The game was selling for up to $500 on eBay! Cephalofair had to reprint the game, and, as of 2018, Gloomhaven was in its fourth reprinting.

Prototyping and playtesting —repeatedly—is all about getting the game ready for people to buy it.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION

Why are game design and game development considered to be different parts of the game-making process?

We’ve looked at some pretty amazing games that are available to play right now. What about the future? What kinds of games are we going to be laying out on the kitchen table in the years to come? We’ll look at some ideas in the next chapter!

MAKE A GAME #4: MAKE A PAPER PROTOTYPE

Before game developers build a board and all the other components of the game, they often test the idea out on paper first. The goal at this stage is just to find out if the concept is fun—and worth pursuing.

›Draw the board for your game on paper. You can also design it on a computer and print it out on plain paper.

›Assemble the game pieces you need. You can use items from around the house, such as coins or paperclips. Or you can borrow game pieces from games you own. (You’ll make some pieces in later activities!)

›Write out the rules for your game. Be very specific. At this point it’s better to write too much than too little.

›Recruit some friends to playtest your game. Have them read the rules and then play your game!

›Observe what works and what doesn’t. Write your observations in your design notebook.

›Make changes to your game and the rules. Repeat the playtest!

DID YOU KNOW?

When a game appears on Wil Wheaton’s web series, TableTop, sales of that game skyrocket. This is called the “Wheaton Effect.”

Try This!

Interview your friends to see what they liked and didn’t like about the game. Write this in your design notebook.

Meeples are a type of game token used in many European-style games, such as Carcassonne. Meeples usually represent people in a game. They can be workers, armies, settlers, or something else. The word meeple is a combination of “my” and “people.” Other game tokens can represent money earned, property bought, lands conquered, disease outbreaks, and more.

›Design your meeple. In most games, meeples look like miniature gingerbread men or women. Yours can look however you like! Typical meeples range from about ½-inch to 1½-inches tall. Yours can be any size of your choosing.

›Draw the meeple shapes on stiff paper, such as card or chipboard. You may also draw the meeples using a computer program and then print them out on cardstock. Many printers can handle thicker paper.

›For each meeple, cut out several of the shapes.

›Glue the shapes together in layers until each meeple is thick enough to stand up. Make as many meeples as you might need for your game.

›If you used chipboard or cardstock that was one color, paint your meeples! This allows you to add detail to your game tokens.

Try This!

Make many more types of tokens in this way, such as a coin or a hexagon or anything else you need for your game.

MAKE A GAME #6: MAKE A GAME BOARD

Most tabletop games have a game board. When designers make a prototype, they sometimes draw the game board on paper for initial playtests. For later ones, though, designers might make a board out of chipboard.

›Design your game board. For this activity, the board should fit on one 8½-by-11-inch piece of paper. You can draw it on the paper or print it out from a computer.

›Cut some poster board or chipboard to the same size as the paper board, plus an extra quarter-inch all around.

›Glue the back of the paper game board to the chipboard. Carefully smooth out the glue so there are no wrinkles in your game board.

›Carefully stick some contact paper to the back of the game board. Smooth out any air bubbles and trim the edges.

›Put binding or duct tape along the edges of the board. This will make a nice edge all the way around your board.

›Now you have a sturdy game board!

Try This!

Design a folding game board that fits on two sheets of 8½-by-11 -inch paper. Follow the above directions—except before you put the binding tape on the edges, use the binding tape (on the underside) to join the two sides together. Leave a small gap so the board will fold in half. Why is a portable game convenient?

In Chapter 1, you learned how to make playing cards with block-printed backs. This time, you’re going to make cards for your board game. You’ll prototype like the pros!

›Design the faces of the cards you need for your game. You can do this using a computer and then printing them out or you can draw each by hand.

›Cut out each card face. They should be the same size or smaller than a standard playing card.

›Insert your cards into card sleeves so that the face is visible. Then place a playing card behind the card within the sleeve. Adding the playing card makes your card stiff enough to shuffle and deal.

›If you don’t have card sleeves, glue a discarded playing card to the back of each of your cards. Low-value Magic cards or cards from a deck of regular playing cards are options.

›Shuffle and deal your cards! You’re ready to playtest.

DID YOU KNOW?

In 2013, Wil Wheaton and Felicia Day held the first International Tabletop day. During it, they played numerous board games online. By the next year, the event spread worldwide with participants in 80 countries.

Try This!

If you’d like to use smaller cards for your board game, try using business cards!

MAKE A GAME #8: PLAYTEST, PLAYTEST, PLAYTEST!

After you construct the game board, cards, meeples, and other tokens you might need, you’re ready to playtest! If you need other components, such as dice or spinners, scavenge them from other games you own.

›If you haven’t done so already, make sure that the rules of the game are clear. Set up the game components.

›Invite some friends or family members to play. Have your testers read the rules and then play the game.

›As they play, note anything that isn’t clear or doesn’t seem to work. Jot that in your design notebook.

›Interview the players after a round. How did they like the game? What didn’t they like? Did they understand the rules? What worked well? What didn’t work for them?

›Make changes to your game. Playtest again!

Try This!

Once you’ve playtested the game a few times and made adjustments, invite some new people to playtest it. Again, see if they can follow your written rules without you explaining anything!

MAKE A GAME #9: MAKE A GAME BOX

First impressions often make a big difference in how a game is received. In later stages of playtesting, game developers often craft the packaging for the game. Not only does this keep the pieces together, but developers can also test out whether players like the way the game looks.

›Pick out a gift box that’s big enough to fit your game board and pieces. You can find inexpensive gift boxes at a dollar store if you don’t have any around the house.

›Design the cover for your box. You can draw and letter it by hand or design it on a computer and print it out. Depending on the size of the box, you might have to create and assemble it in sections.

›Cut out chipboard to fit inside the lid and bottom of the gift box. You can also cut out rectangular strips for the inner sides of the box.

›Glue the chipboard to the inside of the gift box to make the box sturdy.

›Glue your artwork to the outside of the box.

›Put your game pieces in the box.

DID YOU KNOW?

Scrabble is an official sport of several African countries, including Senegal and Mali.

Try This!

Using leftover chipboard, make dividers for the interior of the box. You can use the sections to store game pieces. Can you find existing games that do this well?