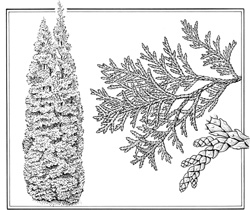

Recently, we found ourselves committing a crime in broad daylight. We pilfered five cuttings from an arborvitae growing at a rest stop on the New Jersey Turnpike. The plant was an old acquaintance. It wasn’t any arborvitae we knew, not the lance-shaped ‘Holmstrup’ or lustrous ‘Green Emerald’ and certainly not the elegant old ‘Pyramidalis’ or winter-black ‘Nigra’ or fat, serviceable ‘Techny’. All are excellent in their way, for there is no such thing as an ugly arborvitae unless it is sick or mistreated. But the specimen that attracted our attention was extraordinary—about five feet high, a dense dark green and breathtakingly healthy, and as conical as an upturned paper

per watercooler cup. We experienced a lapse in morality and took some of it.

We wonder, though, whether another plant could have so quickly lured us into crime. Probably. And especially if it was the right season to take cuttings and we knew they would root easily. We certainly recall the dubious origins of several boxwoods in the garden, though we swear not one of them was taken from either Mount Vernon or Monticello. In our early years as gardeners we committed worse crimes too, with assorted groundcovers and even greenhouse plants. The morals of young people are often a little loose, and we suspect—actually we know—that the morals of young gardeners are the loosest of all.

Arborvitaes have been special to our garden from its very beginning. In as cold a garden as this, various cultivars of Thuja occidentalis are the only dense and narrow evergreen we can count on. The species (hardy from Zones 2 to 8) is native all along the eastern seaboard, but it favors the colder states. If you drive up I-89 through Vermont, at a certain point you will see it growing out of rock outcroppings and forming dense thickets near the edges of ponds. And that is another of its values. For though naturally occurring specimens in thin, rocky soil or with their roots almost in water are never very attractive, they still survive, indicating tolerance to an unusually wide range of cultural conditions. The native eastern arborvitae is a very rugged plant.

This innate toughness also seems to have earned the whole species scorn from people who think of themselves as discerning gardeners, for the rarest forms of eastern arborvitae are as easy to root and grow as the straight species. They all transplant readily, with relatively small burlapped root balls, and unless they are really abused, they settle easily into place—almost any place—and do what they were bought to do. These characteristics have made them both bread-and-butter plants for nurserymen and the darlings of developers, who can instantly dress up a raw new house with a pair at each corner and another pair flanking the front steps. Anyone who buys such a house should immediately move those arborvitae to a place where their innate nobility can freely develop. And any gardener who considers them common is just simply a fool.

There are more wonderful cultivars of T. occidentalis than we know, but a handful (sometimes, alas, literally speaking) have been very important in the development of our garden. A loose folded hedge of ten T. occidentalis ‘Nigra’ was planted along the roadside edge of our perennial garden to screen it from view, and over the years they have grown to towering, thirty-foot-high trees, though still branched to the ground. They have eaten the telephone wires along the road that were such an affliction when we started to make our garden. An equally monumental trio forms the defining barrier between the lower lawn and the rock garden, hiding it from view so it seems a complete surprise, as should any special part of any garden. And though we do not think thirty years is such a very long time, all these specimens of T. occidentalis ‘Nigra’ give the garden a sense of permanence and settled age. They are not really black, as the cultivar name seems to indicate, but they do remain a handsome, healthy grass green all winter, avoiding the rusty, yellowish pigmentation that disfigures wild roadside plants.

Early in the garden’s history, Eleanor Clarke gave us a rooted cutting of ‘Holmstrup’, still unaccountably rare in trade though it is perhaps the handsomest of all cultivars of eastern arborvitae, looking—when it is old and well grown—very like the Italian cypresses in early Renaissance paintings. Over twenty-five years, our original plant has become an elegant twenty-foot-tall spire behind the thyme terrace, where we sit most times in summer when we sit at all. We took cuttings of it when it was about as tall as we are, and they taught us a strange thing. Cuttings taken near the top have grown into equally imposing spires throughout the garden, serving as markers and transition points. But those we took from lower down on our original plant have produced only fat little blobs, cute in their way and very useful, but still blobs. So, unless that is what you want, harvest cuttings from upright growth high on any plant so that the columnar or pyramidal shape for which arborvitaes are mostly valued will occur.

Our love of Wagner’s operas first commended ‘Rheingold’ to us when it was a smug yellow pyramid sitting in a black plastic nursery can. We also treasured its golden foliage—scales really—which kept their clear color summer and winter alike. It is still precious for that, since gold in any form is valuable to a northern garden, always bringing in sunlight, even on days drizzly with rain. What we didn’t know was that ‘Rhein-gold’, as it develops, forms secondary spires of varying heights, making little landscapes all by itself. That characteristic gave us a clue to the use of other evergreens. We frequently plant single specimens in clumps to form not one spire of growth, but many, in a thicket. It is always a magical effect, like mountains piled in front of one another. And we are not the first to admire it, for Gertrude Jekyll noted in her book Wood and Garden that junipers tipped to the ground by storms made similar beautiful thickets, as if many trees had sprouted from one place.

We were very slow to discover T. plicata, the western arborvitae. But when we look at it now we wonder what took us so long. You’d of course know it for an arborvitae, from its conical growth and its branches, cinnamon-colored with age and covered with deep green scales when young. Its twigs have the fingered look it shares with its eastern cousin. But it is potentially a much bigger tree than any eastern arborvitae, growing to two hundred feet in the Pacific Northwest where it is native, but closer to thirty feet in the other places it is willing to grow. It also has the miraculous capacity of being deerproof, though the near famine conditions of the eastern American deer herd make us doubt that anything will be that, eventually. We have found it invaluable for its stately, dark presence, which can harmonize outbuildings, mask offensive views, provide logical turnings for paths or terminus points in the garden. Standing as a single specimen on a lawn or against a woodland edge, it is perhaps the most splendid evergreen tree that gardeners in Zones 4 and 5 can grow.

There are other arborvitae throughout the garden. Comfortable, two-foot-tall pillows of T. occidentalis‘Woodwardii’ are scattered about, and there is a stately single specimen of ‘Elegantissima’ that provides a full stop to the rose path before the stones turn and become the back woodland walk. It is a broad pyramid about twenty feet tall, and though it is chiefly prized for its delicate pale gold growth in spring, that quickly turns to green with summer’s warmth. But the sweet-smelling autumn clematis (Clematis terniflora) has threaded its way through to the very top, and in September flows downward in a lacy fragrant cloud. That arborvitae, at least, was bought from Weston Nurseries, and came on the very first truck of plants to arrive here, in 1977. The clematis, on the other hand, was a gift from nature.

We should blush, we suppose, in confessing how many arborvitae came here as pilfered cuttings—dwarf, gold, thread-needled, variegated, or weeping. But we know that all gardeners live in sin. Who among us is free from the Seven Deadly Sins of Pride, Covetousness, Lust, Sloth, Anger, Envy, or Glut-tony? It is that last and worst sin, for gardeners, that caused us to pilfer more cuttings of that arborvitae on the New Jersey Turnpike than we really needed. We actually took ten. But if they all root, we can share our excess with other gardeners, thus easing some of the burden on our guilty conscience.