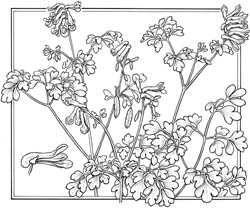

FEW GARDENERS can resist a fern, or something that looks like one. So all by themselves, the delicate, finely divided leaves of corydalis always win hearts. But unlike ferns, corydalis produce dainty racemes of four-petaled tubular flowers that look like little stretched-out snapdragons, or possibly like schools of tiny fish swimming just above the leaves. Their delicate beauty suggests fine porcelain or a rare botanical print. Even the name (pronounced co-RI-da-lis) is pretty, from the ancient Greek word for “lark” because each flower bears a nectar spur at its base that resembles the spurred feet of that bird. Collectively, the genus carries the very old popular name Fumitory, from the Latin fumus terrae, “smoke of the earth,” because the leaves of many species are a delicate shade of blue-gray or purplish blue.

Many corydalis are notoriously cranky to establish and keep in the garden. But fortunately, many years ago, we started out with Corydalis lutea, one of the prettiest and easiest to grow. It produces clumps of ferny leaves about one foot tall, and its three-quarter-inch-long flowers are a blend of yellow and white, like quickly scrambled eggs. It is never so happy as when it can find a crevice in an old stone wall, where it will flourish seemingly only on dust and air. In fact, however, old stone walls usually have a core of rich humus within, made up of years of decomposed leaves and debris falling on and through them. We had no such walls on our property, but we knew how to fake them. And we had plenty of fieldstone, usually at least one with every shovel-thrust into the dirt. So we constructed wall beds—”planted walls” as they are called by rock gardeners—across the front of our lower greenhouse and on its shady side. The stones are essentially a veneer, behind which is a core of stiff gravelly soil. The lichens that come quickly on exposed fieldstone increase the impression that the walls are very, very old.

We planted a single C. lutea halfway up the wall on the shaded side of the greenhouse, since we had read that it would flourish in cool, shady rock crevices. All corydalis are unwilling transplanters, and the usual advice is to buy a plant, set it in its pot near a likely place, water it all summer, and wait for seedlings. But we were impatient, and more than a little cocky in our confidence, so we gently bare-rooted our first specimen and planted it directly in the wall as it was built. By luck or skill (probably the former), it took hold, grew vigorously, and within a year or two, small plants began showing up in other crevices along the wall, not only on the shaded side but also across the sunny greenhouse face. For once a single plant is well established, C. lutea is uncanny at finding the places it likes to grow. It has even made its way, somehow, up the whole length of the property to appear in the low retaining walls of the perennial garden. Experienced gardeners of a snobbish bent call it a weed because of its promiscuity. But if that is so, it is such a pretty weed that we are content to let it come where it will, most of the time. We yank it out only when its ferny growth, light as it seems, threatens to smother out a more precious plant.

Corydalis ochroleuca is quite similar to C. lutea, though it bears slightly pendulous flowers of creamy appearance, with more white than yolk in them. It is also as easy to grow, though it so far sits comfortably in a trough garden in back of the house and refuses to produce seedlings. We are sorry for that, because the two plants grown together would be a wonderful blend of creamy white and light yellow. A magical effect is always created when flowers of two or more closely related shades mingle. Perhaps it will happen yet.

There are seventy species in the genus Corydalis, most of which share the family birthright of grace and beauty, but many are very rare and can be quite fussy if their preferences are not exactly suited. Those preferences are usually—not always—for deep, humus-rich woodland soil that is constantly moist but never waterlogged. Light, dappled shade is best, such as would be provided by high old trees, but sometimes the canopy of a large shrub provides a perfect spot. They are not greedy feeders, and so fertilizers should be withheld, especially granular ones that can burn their sensitive roots. Still, a very dilute wash with liquid fertilizer, such as Peters 20-20-20, at half the strength called for on the package, can often encourage weak plants to catch hold and thrive.

Among the true woodland species, C. cava is the easiest to grow, producing airy, blue-green, fringy leaves topped by cobs of flower of a haunting misty lilac, making it seem especially fumitory. Even in the cool, moist shade it demands, it is apt to melt away in summer heat, causing anxious gardeners to fret. But it will usually reappear with the cool rains of either autumn or the following spring. Corydalis solida differs from it in that its tuberous roots are solid rather than hollow, a trivial botanical distinction that would not prevent most gardeners from thinking it just as wonderful. In the “pure” form (if such actually exists), it shares the predominately lavender or purplish color of C . cava, though it has given rise to many wonderful seedlings and crosses with pink, cherry-red, or even coral-colored flowers.

Corydalis dyphilla is also irresistible, not so much for its leaves, which are the least delicate of all, as for its upended dancing flowers. They appear in mid-spring, colored a pale whitish mauve with violet-purple lips and throat. Each flower, hardly an inch long, is carried loosely above the foliage in a panicle of six or eight others that seem to nod to one another in curious animation. All corydalis require good drainage at their roots, but give this one the best gritty soil you have, in light shade or morning sun.

As corydalis gain in popularity, more species and hybrids seem to appear each year. Among those recently made available, the present aristocrat is C. flexuosa. For one thing, its flowers are an electric blue, produced in late spring above foot-tall fringy growth, and to many gardeners blue is the best color a flower can come in. Several selections have been made, of which the best are ‘Père David’, with turquoise flowers; ‘Blue Panda’, almost gentian blue; and ‘China Blue’, with royal blue flowers animated at their tips by a spot of purple and white. More than one gardener has noted that the flowers, with prominent upturned spurs and flared mouths, resemble a school of tiny, vivid blue tropical fish. We have grown them all, but we’d have to confess, not as well as we would like. Our best claim would be, perhaps, that they persist here, offering us enough encouragement to keep trying. Give all forms of C.flexuosa the coolest, richest spot in the garden, in moist, dappled shade, and when they go dormant in the heat of summer, pray for their return in spring.

The Russian C. turtschaninovii, though impossible to pronounce, is far easier to grow. At its best, as in the collected form ‘Blue Gem’, the flowers are bluer than any gentian or delphinium. In ‘Eric the Red’, the blue flowers are set off against copper-hued foliage for a frankly breathtaking effect.

Among the blue- or purple-flowered corydalis is the nicely named ‘Blackberry Wine’, which was introduced only in 2001 but has quickly become a sensation. Its name serves it well, for its flowers are a complex blend of deep and pale purple shading to blue. And though many corydalis possess a slight, delicate fragrance, ‘Blackberry Wine’ is rich in scent. To all its other virtues it adds ease of cultivation. Its parentage is vexingly uncertain, though its tolerance of heat and sun suggest our old friend C. lutea. If that is in fact one of Blackberry Wine’s parents, whether it will seed about as freely remains to be hoped for.

Most corydalis cultivated in gardens are perennials—or at least, you hope they will be perennials—but the genus contains annual and biennial species as well. Among the annuals the most charming is C. sempervirens. It is a much-loved native American wildflower with a range from Nova Scotia to Georgia, and the only corydalis we know of that has its own popular name, rock harlequin. It is typically found growing on thin soils atop rocky ledges, but once established in gardens, it faithfully returns from year to year, its airy sprays of flower appearing on delicate, ferny plants up to two feet tall. The flowers are an engaging blend of color, each tube beginning pale yellow and then transitioning into hot pink, just the sort of costume Harlequin might wear.

All these corydalis grow in our Vermont garden, so their hardiness extends northward at least to a cold Zone 5, but southward only to Zone 7 or so, for they all dislike summer heat. Their greatest enemy is heavy clay, all too common in the upper South, the Ohio River Valley, and parts of the Midwest. If we gardened in those areas, we would have a bucket of sharp builder’s sand ready to dig into the soil while the corydalis was still in its nursery can. Digging in a bucket of good compost or well-rotted cow manure is also always a very good idea, anywhere. All this is trouble, of course, but corydalis are worth it. For some, such as the wonderful coral-flowered C. solida‘George Baker’ that has (so far) eluded us, we would dig in pearls, if we had them.