IT TOOK US MANY YEARS to understand the specific needs of nerines. Thirty, to be precise, because it was that long ago that we acquired our first one from beside the garbage can of a friend in Marblehead, Massachusetts. “They are one-shot deals,” he explained, “like paperwhites. You can’t make them bloom again.” But they seemed so promising, each one sitting on top of the soil and looking like a fat daffodil bulb. There wasn’t any foliage, but there was one wizened pink flower on a long stem that seemed to tug at us. Anyway, bulbs always give you that feeling of potential life that makes them hard to throw away, even if they are only sprouted onions in the crisper drawer. The bulbs were shoulder-to-shoulder, not nicely spaced like you’d plant a pot of tulips for forcing, but joined at the base and pressing against the rim, as if they had multiplied to that extent. And there was also the pot, an old clay one, white-crusted with lime. In any case, at that time we seemed to be running a Shelter for Unloved Plants, rescuing half-frozen ficus trees from city curbs and shrunken, dust-covered African violets from the rubbish room of our apartment building. So we took these nerines. At the least, the pot would be nice to have.

The first thing you feel about anything you rescue is that you should be especially good to it. So we tipped those nerine bulbs out of their pot, divided them carefully, and then repotted them into two pots, the first the one they came in and the other recycled from somewhere else. We used the richest compost we had, and fertilized them carefully all that first winter, during which very healthy, straplike, eight-inch-long leaves appeared. We were really hoping for abundant bloom in autumn—from two pots now—but nothing came. Our plants ripened their leaves and then quietly went to sleep for the winter. This happened for several years, but as they were no trouble and we had hopes that flowers would eventually occur, the two pots just hung around. But still, our friend had been right. They seemed a “one-shot deal.” And we hadn’t even had the first shot.

Then we had the great privilege of visiting a very old garden in a small village in Normandy that had been tended for over forty years by its owner, the Comtesse d’Andlau. Like many antique French houses, hers presented a blank north face flat on the street, but its south side opened through wide French doors into a large walled garden. When the house was built in the eighteenth century, much of that space would have been a paddock, a small home orchard, a place to tether the family cow or even to raise a pig or two. But it was now planted with remarkable trees and shrubs, some—like the white-berried Sorbus cashmiriana—of extraordinary credentials. (“Clementine Churchill gave me seed of that.”)

Sadly, our visit was in late October, on a cold gray and drizzly day, and mostly there was little to admire in the garden except bark, berries, and impressive plant labels. But as our little group turned back toward the house, we noticed that the whole of the narrow bed between the old stone terrace and the French doors was vivid with carmine and coral pink, white and purple. We must have given a gasp of surprise, because Mme d’Andlau said, in her richly accented English, “Very fine, do you not think? They are nerines. Of course, you must not be too good to them!” Of course. For there was the mystery solved, in fewer than ten words: You must not be too good to them.

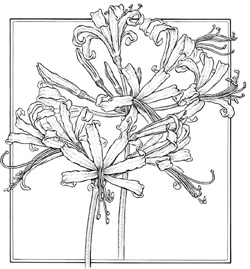

Two species of nerine are commonly grown in gardens where they are hardy, and in pots elsewhere. Nerine sarniensis was cultivated in France by at least 1630, and in Guernsey by around 1655. It is popularly known as the Guernsey lily because of the supposition that large numbers of bulbs washed ashore from a foundered Dutch merchant ship, took root on the shores of that island, and flourished. This watery survival gives the genus its pretty name, after Nerine, a water nymph, and the species name derives from Sarnia, the ancient Roman name for the Isle of Guernsey. But though N. sarniensis thrives in the mild maritime climate Guernsey enjoys, by whatever path it came to be cultivated there, it is magnificent, producing strong bloom stems to as much as eighteen inches tall, topped by an almost spherical umbel of inch-wide, six-petaled flowers. There may be as many as twenty separate flowers in an umbel, from each of which protrude prominent stamens, rather like the whiskers of a cat. The color of the typical species is an extraordinary rich scarlet dusted over with flecks of gold. It is hard to better, though there are beautiful selections that may be pinkish white, strong pink, or orange.

Our nerine—the one that came to us from beside our friend’s garbage can years ago—is N. bowdenii, first introduced into gardens by Athelstan Bowden-Cornish, a specialist in South African flora, in 1902. In its typical form, it produces bloom stems to about fifteen inches tall, each crowned by a rather ragged umbel of two-inch-long, five-petaled flowers of a warm rich pink, ruffled along their edges and often marked with pencilings of darker pink. That seems to be the form we have had for years, though it is now relatively rare in commerce, having been superceded by hybrids that produce fuller umbels of apricot, coral, peach, pink, grape purple, and even icy white. We have some of those too, but we don’t like them all that much better than the form we started with. Or rather, we like them differently. And after we received our clue from Mme d’Andlau, we have not been without nerine flowers in late autumn, ever since.

Actually, she was perhaps only repeating what many good European gardeners know. For Tony Norris, an English nurseryman who accumulated more than eighty thousand nerine bulbs and nine hundred cultivars by the end of his life, observed wild plants of N. sarniensis growing lustily north of Cape Town, South Africa, in some of the worst soil on earth. The chosen habitat of that species is gravelly scree or rock crevices where the nitrogen content of the soil is as low as three parts per million. Norris reasoned, then, that the previous assumption that nerines would relish the fat soils preferred by their cousins in the family Amaryllidaceae—the Hippeastrums—was simple error. He suggested a potting medium of three parts acid sand to one part peat, and no fertilizer. Other specialists have suggested other mixes, though it is certain that the best results occur from lean, fast-draining soil that is poor in nitrogen but fairly rich in phosphorus and potassium. Also, it does no harm to lace the potting medium with a bit of the worst soil in one’s garden, to supply necessary trace elements. On this lean diet, nerines may flourish for ten years or more in a pot, and they ought to be left alone for just about that time, since “Do Not Disturb” is the motto for them all. They will flower best when they become so crowded that their bulbs touch the edges of the pot, in fact just exactly the way the bulbs in that pot we rescued were, before we mistakenly made them more comfortable.

Mme d’Andlau grew her beautiful nerines on garden soil above a bed of ancient brick rubble and decayed mortar. Anyone who gardens in Zone 9 or 10 could do that as well, but the rest of us must grow our nerines in pots. Bulbs are always expensive because named forms can be reproduced only from offsets of mother bulbs, a slow process at best. However, three bulbs established in a six-inch-wide clay pot, with one-half of each bulb showing above soil level, will multiply to ten or so in five or six years, blooming more profusely each year and representing wealth in many senses. After the foliage has withered, the advice repeated in many books is to turn the pots on their sides and place them in the driest, hottest place available, such as on a shelf at the top of the greenhouse, to ripen them for bloom the following autumn. We’ve had better luck, however, by treating our nerines more gently, placing them in sunny, protected places over the summer where a little water—but not much—may occasionally reach them.

However they are stored, they generally tell you when they have woken up by producing a slender bloom stem from the neck of each bulb. This sense of timing is a minor horticultural mystery. When the buds first show, the pots must be brought into strong sunlight, watered sparingly at first, and then more frequently as the flower stems extend and the tips of new leaves begin to appear. In a greenhouse or on a sunny windowsill, the flower stems will always bend toward the strongest light, and so pots should be rotated a quarter turn each day. It is a gentle attention and the most that nerines really want from you.