MANY GARDENERS are in part historians, concerned with creating garden effects that are redolent of other places, other times. And for them, one of the most precious parts of gardening is the sense of being in their own place while also catching whispers of being somewhere else. It is partly for this reason that gardeners so much value potted plants in the landscape. No one knows for sure how early the realization occurred that plants could be grown in containers, though the skill was well understood in Egypt by 4000 b.c., and certainly had been learned from even more ancient Babylonian and Mesopotamians practice. In our time, growing plants in containers is as obvious as boiling water in a pot, and every kitchen windowsill has at one time been graced (or disfigured) by a potted plant, briefly for show or in permanent residence.

But when you think of it, scooping a plant out of the earth, establishing it in an earthenware jar or stone basin, determining its needs for drainage and extra nutrients and water, finding the right exposure of sun or shadow—those are all earth-shaking discoveries to gardeners, equal practically to the discovery of the wheel. And if it is true (it is at least fancifully true) that our development as individuals recapitulates the development of the species as a whole, then child gardeners begin just where the Mesopotamians and Babylonians did, with the joyful discovery that a plant growing in the earth could also grow in a container. And better, it could also be portable, for carrying things from here to there is very important to a child.

The portability of potted plants has been of inestimable importance to our species as a whole. The discovery of container gardening made possible the transport of plants from far places and actually began the endless exploration of plant hardiness, which really is only a determination of whether something that grows far away can also grow here, in whatever country and place gardening occurs. Some cuttings and bare-rooted plants could endure long transport and still survive. Witness the banana, the best forms of which never set seed, yet were “disseminated” as basal cuttings with a bit of root tissue all throughout the subtropical world long before Columbus made his famous voyages. An important food source, bananas could be transported with very little earth about their roots, and reestablished far from Southeast Asia, which is their original home. In the seventeenth century, when the great importation of plants began, fruit from potted citrus and pineapples graced the Christmas tables of titled and wealthy gardeners from Germany and France through Poland to Russia, grown in stove houses and orangeries that allowed the tubbed trees and plants only a brief summer vacation. Actually, the history of potted plants seems almost as long as the history of human civilization. And the cultivation of plants in pots has a significance that extends through the entire band of human concern from pure sustenance and utility to the highest levels of horticultural embellishment.

There must be strong resonance of all that for anyone who grows a plant in a pot. For committed gardeners, however, it is also an essential act, making possible the cultivation of something rare, something special, in a way that gives it an intimate focus and keeps it under the eye until it is known. Then it might spend its entire life in a pot if it is not hardy, or planted out into the garden if it is. Or perhaps just discarded. For it is a fact about pot culture that it is easier, somehow, to upend a potted plant into the compost than to hoick it out of borders and beds. Plants grown in pots also allow for endless experiment, and for that reason, in our many years as gardeners, we have gone through a huge number. Some, such as our Xanthorrhoea, now over thirty years old, or our bay tree, almost that venerable, seem apt to remain for the rest of our time in this garden, if not even longer. Others we have grown we hardly remember. They are “leptospermums without number . . .”

This we do know, however. The sure mark of a lovingly tended garden, whether it is a great estate or a simple cottage, is a clutter of choice plants in pots and tubs, all in thriving good health. Most will be tender plants, gardenias or citrus, begonias or camellias. And some will reveal surprising histories, originating as cuttings given by great-aunts or far-flung cousins, or inherited from grandmothers, family heirlooms that go back a hundred years in a single trunk and leaves.

There are so many plants, also, that simply will not agree to live where you live, except in a pot. They are too tender for your winters, or they dislike your soil, or—and this is often the case with very small properties, or with gardeners who are reduced to cultivating on a balcony—there just isn’t room elsewhere. We are always touched by the shifts and contrivances gardeners exercise to save a precious plant over the winter, or to transport it many miles away to a new home. We’ve done a lot of that ourselves. And we have known for many years that almost the heart of gardening lies in cultivating plants in containers. Most plants, after all, enter the garden that way, and a good many might also leave it in the same manner.

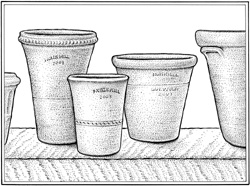

In the matter of the pots themselves, we are very particular. They must be of clay, as was most anciently the case, and good clay if we can afford it. There is no argument that plastic pots are easier to maintain, for it is simply true. They do not break, and they endure severe weather without punking into slivers. Moisture levels are much easier to maintain because the walls of plastic pots do not constantly transpire moisture as clay ones do. It must even be confessed that some plants actually prefer growing in plastic pots. For these reasons, plastic pots are the nurseryman’s darlings, manufactured (and discarded) in countless millions. Burn just one in the fireplace, and you will know the oil-based energy they contain. Now they can even be bought in stylish models that are advertised as looking exactly like good Italian pottery but able to withstand the worst rigors of winter. That may be true until you thump them. For then, instead of the rich ring of a clay pot, you get a hollow plunk sound. Most gardeners don’t need to thump, however. Any plastic pot is as unmistakable for what it is as an artificial flower on a tombstone, and no one is really ever fooled. Even common clay pots from the local hardware store are vastly to be preferred, for with one season they take on a wonderful patina, a whitey encrustation that forms over the brick-red surface as salts and lime dissolve and weep through the porous walls. If heavy, thick-walled pots are inherited, or found in junk shops, garage sales, or even town dumps, they are especially to be treasured, for they are sturdier than most modern ware and they already possess the grace of age. Sometimes, one might even find one that broke a century ago, and was patiently put back together with wire brads. That is a great treasure for the care and thrift it shows.

For many years, our clay pots either came from the local farm supply store or were lucky finds we stumbled on in the corner of some old nursery that had shifted to the convenience of plastic or was going out of business. In fashionable antiques shops we occasionally splurged on a fine old English or French pot, and once, in Florence, we bought three Impreneta pots with rolled rims, made in the same way since the Italian Renaissance. We brought them home on the plane in our laps, at a time when you were still allowed to do such things. Then, about fifteen years ago, we met Guy Wolff, and our whole pot habit altered. For he was willing to make hand-thrown clay pots to antique designs, and that is what we wanted. It must be said that the first experiments were not a success, but quickly Guy came to understand this medium, new to him, and the pots grew finer and finer. Now, working from historic fragments, his pots are without compare, and our collection is enriched each year by a new firing.

Among the many models he makes, our favorite perhaps is taken from the portrait of the myopic young Rubens Peale, painted by his brother Rembrandt, in which Rubens lovingly holds an old clay pot with one of the first pelargoniums grown in America. It is a scrawny thing, and Rubens, though charming, is not precisely a handsome man. But the pot is beautiful, and its reincarnations under Guy’s hands line our greenhouse benches and when empty are displayed on shelves in our potting shed. We will never have enough of them.