CHAPTER 4

TRIBAL ORGANIZATION

While we are used to thinking of Indian people as living in tribes with particular names, many of the common ways of describing human organization on the Plains actually mask the complex realities of social and political life. It is necessary to understand the true variety of social units that Plains Indians participated in, and their structure and purposes. Apart from the large-order groups usually termed “tribes,” these units include kinship-based bands and clans, as well as associations or clubs formed by non-kinsmen. Special attention should be paid to the Native names for these units, the reasons for forming them, and the leadership positions that emerge in them.

TRIBES, BANDS, AND CLANS

The Notion of Tribe

The word tribe has been used in a number of different and often contradictory ways. Originally, it was applied to segments of ancient state societies in Israel, Greece, and Rome. The Roman historian Tacitus described the various groups of Germanic people that the Romans encountered as “tribes,” also extending the meaning to groups outside the state. Many subsequent writers have applied the term very broadly to non-European societies without exactness about their size or degree of integration, although normally with the implication that tribal societies were primitive and European ones civilized. Others have proposed a very specific, though ultimately difficult to support, evolutionary meaning for “tribe,” reserving it for societies in the middle range of complexity, between small hunting and gathering societies organized in bands and large, complex chiefdoms and states. In this usage the term denotes people living by horticulture, simple agriculture, or pastoralism.

It was the broader application of “tribe” that led to its conventional use by non-Indian explorers, government officials, and the general public in describing the polities of Native North Americans. During the twentieth century, the governments formed by American Indians on reservations and in other Native communities also perpetuated this convention by frequently naming and referring to their organizations as “tribes,” although more recently the term “nation” has often replaced “tribe” in self-designations. This kind of Native response to outsiders’ expectations of structure and leadership was also common during the period of subjugation, when groups were essentially forced to represent themselves as “tribes” with “chiefs” in order to negotiate with colonizers. In recognition of this phenomenon, another proposed technical way of defining “tribe” is as a kind of organization produced from the interaction between large powerful state societies and the smaller societies they colonize. All of these uses of the term “tribe,” however, tell us more about non-Indian perceptions of other people than about the people themselves.

Thus, American Indian people and those interested in their way of life are stuck with a term that has many meanings, no one of which can be supported theoretically. Still, it would be very difficult to avoid talking about Indian groups as tribes because the word has become ingrained in our thinking and writing; this book will not avoid the word. But it is most useful to approach the term critically—to consider some of the supposed characteristics of tribes and ask whether they apply to particular Plains populations of the pre-reservation era. These criteria are both cultural and political in nature.

One idea is that members of a tribe share a common language. In general, common language is evident among most of the groups customarily recognized on the Plains as tribes. Sometimes, though, language is not uniform or totally distinctive. The wide-ranging Comanches displayed multiple dialects with different words and pronunciations. These differences were evident as late as World War II, when Comanche men were brought together in the U.S. Army to serve as “code talkers” (native-language radio operators) and had to agree on a fully common vocabulary. At the same time, the Comanche language is virtually identical to that of the Shoshones to the west of the Plains; on the basis of language alone, one might argue that the Comanches and Shoshones composed one tribe. Other measures of cultural homogeneity have also been attached to the idea of tribe, and again on the Plains, groups often display unity. The particulars of tipi construction, moccasin shape, arrow decoration, and the colors and designs of beadwork motifs are some of the many ways that people announced their group affiliation.

Geographic continuity is another common marker of the so-called tribe. Plains groups could be said to have contiguous territories but only in an artificial way. They generally maintained an internal sense of range and boundary, but the nomadic groups traveled far and wide and territories were subject to continual renegotiation. It has been argued that tribal groups derive their sense of spatial bounding because of conflict with outside groups, and it certainly was the case that warfare contributed to notions of border and group identity on the Plains.

Related to the idea of geographical connection is the qualification that a tribe unites all its members in some encampment or ceremony, at least occasionally. This standard was met by some Plains Indian groups, such as the Cheyennes and Kiowas, while other people we think of as constituting a tribe, such as the Comanches, never all gathered together in a single location. Even those groups with the custom of an annual meeting sometimes canceled them, during years when food was either too scarce to support a huge camp or, in a few cases, so plentiful that cooperation was considered unnecessary.

Other criteria for tribal status have to do with leadership and political unity. A single powerful leader in charge of a large group might suggest a “tribal” level of integration. Such leadership was only sometimes evident among the Plains groups. Often, instead, there were multiple headmen leading smaller groups, and perhaps councils made up of these headmen. Councils were well institutionalized in some groups, while in other groups they were more temporary, convened only to deal with specific problems.

Integration across large numbers of people could also be achieved in other ways. Intermarriage among kin groups, as required by rules forbidding sex and marriage between relatives, achieved a measure of interconnection. Another means of unifying large groups was the non-kin association, a kind of club that potentially drew its membership from all families, and provided some service to all of them, and so functioned as an overarching and uniting structure. Yet another criterion for tribal integration, related to these others, was the presence of formal ways for limiting violence within the group. All of the Plains societies had customs for controlling disputes, and most had clubs whose members acted as temporary peace officers. One can imagine that all of the usual criteria for “tribal” organization would in fact emerge in any number of combinations and degrees in different groups, and that is what happens across Native North America and the Plains.

Bands

The notion of “band” rather than “tribe” is somewhat more helpful in understanding Plains human organization. Most everyday Indian thinking and activity about affiliation were directed at forging and maintaining bands rather than larger groups. The band is a small group of people who live and work together for mutual advantage. A single nuclear family (parents and their children) could function in this way, though normally the term indicates an extended group beyond the nuclear family; in the evolutionary schemes that have been put forth, the band is the primal social form beyond the family. Bands nevertheless grow along kinship lines. For example, a band could be started by two brothers who bring together their wives and children, and then other relatives. A group so formed might number 30, 50, or 200 people. Bands are flexible in their membership. There are no strong rules of heredity or work that keep people attached to the group, and they are free to come or go as they judge best. Therefore, bands are also flexible in size; members can gather or disperse as the local food supply grows and shrinks, and this makes them suitable for effective seasonal hunting and gathering.

Bands have a distinctive social character. Individual freedom and initiative are valued, but at the same time there is an emphasis on common obligation and equal access to the products of labor. There are relatively few social differences between band members. Differences that come about are the ones that appear most natural, those based on age, gender, and degree of personal ability. The leader that emerges in this egalitarian setting is someone who has an exceptional record as a provider and who gathers followers through personal reputation and charisma. His power rests on his ability to build consensus and inspire action, and he has neither the motivation nor the clout to physically force people to do what he wants.

Band organization often corresponds to bilateral descent. This pattern of tracing relatives through both the mother and father’s sides of the family equally is the one familiar to modern Americans. In bilateral descent, a person need not be equally close to, or even like, all relatives on both the mother’s and father’s sides, but is nevertheless entitled to count them all as kin. Bilateral descent opens up maximum possibilities for developing supportive relationships with relatives, such as would be helpful in nomadic hunting and gathering. Whenever status is gained through individual work and achievement, and individuals can benefit from a wide network of helpful kin, bilateralism is favored. The majority of the groups occupying the Plains during the horse culture period exhibited an emphasis on band formation and observed bilateral descent principles. Either their ancestors already had bilateral descent when they reached the Plains or they abandoned other principles and drifted into using bilateral descent as they became buffalo hunters.

Descent Groups: Lineages and Clans

While bilateral descent allows the widest options as hunters and gatherers seek to form support networks, it is less helpful when people’s survival and personal status depend on passing down property and rights from one generation to the next. When the inheritance of garden land, for example, is important, a single, preestablished, direct line of descent is more likely to limit confusion. So, many societies practice unilineal descent, in which people are related either to their mother or father’s family, but not both. In the version of unilineal descent called matrilineal descent, a person is related to others only through his or her mother and female relatives. In the version known as patrilineal descent, the person connects to relatives only through his or her father and father’s male kin. It makes no difference whether people themselves are male or female, but it is who they trace their relatives through that determines whether descent is matrilineal or patrilineal.

When a unilineal descent principle is followed, the result can be the formation of a group of people with shared descent. This group exists through time, permanently and regardless of which individuals are born into it or die out of it. The unilineal descent group is therefore potentially much more stable than a family or band, which exists only as long as its members are alive and stay together, and this stability is desirable for the long-term possession of cropland and village sites associated with semi-sedentary horticulture. Descent groups that are organized from a known common ancestor are called lineages, and may be referred to as matrilineages or patrilineages depending on whether they trace the maternal or paternal line. An even larger encompassing unit can be formed, harkening back to a common ancestor so far in the past that the ancestor is no longer nameable or is represented as a mythological character. This larger-order descent group is called a clan, and may be termed matriclan or patrician depending on the descent principle.

Clans are corporate groups, with common rights and responsibilities shared by all members. They may own hunting territory or garden land in common, or houses. They may own particular rituals that only they are allowed to practice. Often these rituals express a unique connection to the clan’s ancestor figure. Associated with clan identity and rituals are taboos observed by the members as outward signs of ancestry. For example, a Bear Clan member would be prohibited from eating bear meat. Clans are also frequently corporate with respect to marriage; that is, all clan members observe the same rules about who to marry or not marry. Most often clans follow a rule of exogamy that requires that all members marry someone from a different clan than their own. Exogamous marriage has the effect of linking several clans together through intermarriage.

Membership in a clan is fixed at birth and does not change as the individual marries and has children. In a matrilineal society, the children belong to the clan of the mother, and in a patrilineal one, to the father’s clan. The other parent normally lives with his or her spouse and children and functions as a close, supportive family member, but always belongs to his or her own clan and must devote his or her allegiance to that clan above all else. For instance, in a matrilineal society, one’s father has a different structural position than one’s mother and is more like an in-law who has married into, but not joined, his wife and children’s clan. The father must continue to express allegiance to his own mother’s clan by participating in its ceremonies and supporting the children born to that clan; that is, he has fatherly duties toward his sisters’ children. His devotion to his own wife and offspring is still very important, though, not only for the well-being of his immediate family, but as a public expression of the desirable alliance between the father’s and mother’s clans, for it is these kinds of marriage and family connections in aggregate that tie all of the clans together into a larger, more powerful society.

Matrilineal exogamous clans were found among the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Crows. The Pawnees did not have clans, but their main social unit, the village population, was organized by matrilineal descent. Pawnee villages resembled clans in that they had mythological founders and distinguishing rituals, but they were also like large extended family bands, and they practiced endogamy (marriage within the group) rather than exogamy. Patrilineal clan societies on the Plains included the Osages, Omahas, Poncas, Kansas, and Iowas. Evidence about the Otoes and Missourias is more scant but indicates that they too were patrilineal. Note that the societies with unilineal descent are often linked to each other historically and linguistically, and are either semi-sedentary horticulturalists or have a background in gardening. Traces of matrilineality or patri-lineality have been posited for other tribes by various researchers, either as leftovers from earlier periods or as emerging responses to white-induced trade and warfare, but the presence and causes of these tendencies are frequently debated.

Phratries and Moieties

There are a couple of other kinds of social units larger than the clan that are found in some Plains societies. Sometimes clans link together in pairs or trios to establish regular helpful relations with each other. These sets may or may not have names in the native language or reflect a sense of common descent among the member clans, but they are recognizable through the actions and attitudes of their members. Anthropologists call such a clan set a phratry (plural phratries).

It also happens sometimes that entire societies are split into two halves that play complementary roles to each other in rituals, games, or marriage. In a society with, say, 12 clans, 6 clans would compose one half, and 6 the other. This halving pattern can also sometimes be found in societies without clans. The halves may indicate some wide sense of common descent but are not very important outside of the rituals or games in which the differences are invoked. They have simple distinguishing names like the “Summer People” and the “Winter People” among the Pawnees and “Sky” and “Earth” among the Omahas. A unit of this kind is called a moiety (plural moieties) by anthropologists, after the French word meaning “half.”

Native Naming

For the most accurate sense of how Native people organized, the names that various groups gave themselves must be considered. In general, Indian people recognized themselves as members of large groups with common language and history. The Native names for these large units usually mean something akin to “the people,” “the real people,” or something similar conveying a sense of ultimate humanness. These names have frequently come to be regarded as “tribal” names.

Many of the tribal names in common use today do not originate with the people who bear them, however. Often they are accidental corruptions or misapplied versions of Native names, or insulting nicknames from a neighboring tribe that were adopted into Euro-American speech. In several cases the names come to English through French or Spanish, adding another layer of distortion. “Sioux” is a French shortened version of the name employed by the Algonquian-speaking Indians for certain non-neighbors, possibly connoting “foreigner,” and which is ultimately relatable to their term for the eastern massasauga, a small rattlesnake (leading to a common but imprecise conclusion that the Algonquians were purposefully referring to the Sioux as “snakes”). This name, as seen in Chapter 2, covers three major Plains political-linguistic units that are in turn each formed from multiple large, distinctive divisions made up of numerous bands. “Comanche,” also applied to multiple divisions, comes, via Spanish, from the Ute Indian term meaning, roughly, “other” or “enemy.” “Gros Ventres” and “Nez Perce” (“Big Bellies” and “Pierced Noses” in French, respectively) are other tribal names derived from uncomplimentary misnomers.

The outcomes in defining and naming groups were shaped by particular historical circumstances and the names now in use often disregard people’s own sense of group identity. Naming people is a way of controlling perceptions about them, an act of political determination. The study of ethnonyms (the names of ethnic groups) therefore becomes a means of understanding the nature of interaction between groups.

The Cheyennes make a good case study in the intricacies behind tribal names (as reconstructed by ethnohistorian Douglas Parks, in Moore et al. 2001). The name Cheyenne has been used, first by French and then English speakers, since the late 1700s. The French had adopted the Sioux designation sahiyena, which also appears as sahiyana or sahiyela. In turn this name was derived from sahiya, which the Sioux applied to the Plains Cree; sahiyana includes the diminutive suffix –na, in effect meaning “little Plains Cree,” probably indicating that from an early Sioux perspective, the Cheyennes appeared like another version of the Crees, who were also Algonquians. The name has been commonly translated as Sioux for “red talkers,” supposedly a metaphor for “people of alien speech,” but this derivation appears to be based only on a coincidental resemblance. Another mistaken derivation is from chien, French for “dog.”

The Sioux name for the Cheyennes was widely adopted and modified by other tribes, including the Algonquian Foxes and Shawnees to the east of the Plains and the Caddoan Wichitas of Oklahoma and Texas. Several other Plains tribes, however, including the Crows, Hidatsas, Mandans, and Comanches, referred to the Cheyennes by names in their own languages meaning “striped arrows.” A variation of this idea in Comanche and Shoshone was “painted or striped feather.” As this name idea diffused further it was modified in the receiving languages to mean “striped or spotted blanket” (an alternate name in Crow and Hidatsa), “spotted horse people” (Blackfoot), “striped people” (Blood and Piegan), “spotted eyes” (Flathead), and “scarred people” (Arapaho and Gros Ventre). A few tribes had yet other names. The Kiowas called the Cheyennes “pierced ears” and the Plains Crees, as if to confirm the Sioux characterization, called them “people with a language like Cree.” Finally, the Cheyennes refer to themselves as Tsistsistas, to use the anglicized form, a name meaning “those who are from this (group).”

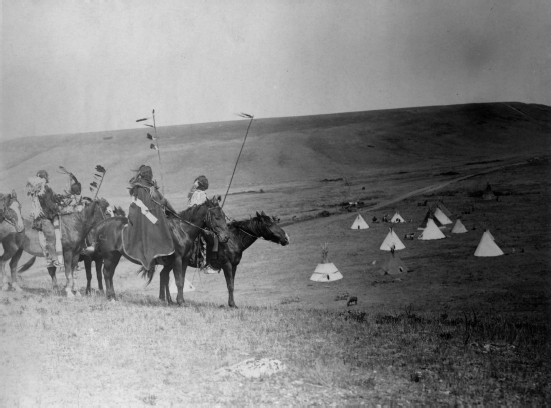

Much more relevant in everyday life were the divisions and bands. People generally identified first with these units and only secondarily with anything larger. Often the band names referred to stories about the groups, their alleged characteristics, and their position in the historical development of the larger society. The Cheyennes had 10 or 11 bands, or sometimes more, each with its proper location on the camp circle, called (in imperfect translation) Aortas, Hair Rope (or Hairy or Rope) Men, Eaters, Ridge Men, Scabby People, and so on. The Aortas were reportedly so named because of an episode in the past when they used a burnt aorta from a buffalo heart as a makeshift tobacco pipe. The Hairy Rope Men were said to prefer ropes of twisted hair instead of the usual rawhide, while the Eaters were said to be liable to eat anything, though they themselves claimed that the name indicated that their ancestors were the best hunters. Around the camp circle of the Kiowas, always in the same position, were divisions called the True Kiowas (presumably the original core), the Elk Men, Saynday’s Son’s Men (Saynday was the trickster character of Kiowa myth), the Big Shields, the Biters, and others. The Plains Crée band names reflected a heritage of maintaining separate hunting territories, a continuation of eastern woodland practice, with environment and location titles such as Parklands People, Beaver Hills People, Prairie People, Calling River People, and Touchwood Hills People.

The names of clans are also revealing. The Omahas had a pattern of clan names seen in many cultures around the world, in which the descent groups were named for mythical ancestors in the form of animals or other elements of nature. Such ancestor emblems are called totems. Omaha patricians had names alluding to the buffalo, buffalo calf, eagle, bird, deer, wolf, bear, elk, turtle, and wind. The mythological animal or element ancestor is an emblem of the solidarity shared by clan members, and it indicates the ancientness of the unit. Symbolically, the totem may stand for certain desirable qualities or behaviors in humans that are also seen in nature. Totemic naming also has the symbolic effect of likening the differences among social groups to the differences among animals in nature. An extension of the idea of totemic naming is to call a clan after the taboo its members observe, such as the Do Not Touch Buffalo Tails and Do Not Touch Deerskin groups among the Poncas.

FIGURE 4.2 The Kiowa camp circle showing locations of bands, as recorded by James Mooney. The Kiowa Apaches (Plains Apaches) had a place among the Kiowa bands. The camp was shaped and oriented like a tipi, and thus was the symbolic house of the entire tribe.

Where totemic clans are found, personal naming practices sometimes also reflect clan membership. The clans had stocks of personal names that were reused as children were born into each generation, all referring in imaginative and poetic ways to the characteristics of the totemic animal. Table 4.1 shows a sampling of the Elk Clan personal names among the Omahas.

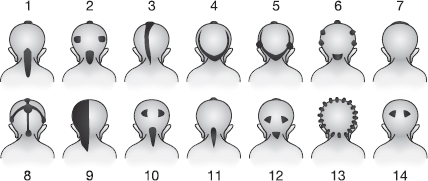

The Omahas and other Southern Siouans carried this practice even further by giving ordinal birth names—names that indicated both a child’s clan membership and its order of birth in the family. In the Elk Clan, a man’s eldest son might be named Soft-horn, the second Yellow-horn, the third Branching-horns, and the fourth Four-horns. Omaha and Osage boys also received distinctive haircuts in which most of the hair was shaved, with patches or locks left to create a design that represented some characteristic of their clan animal. A patch of hair in front and tail down the neck was the “head and tail of the elk”; other patterns represented buffalo horns, a shaggy wolf, or a turtle’s appendages projecting from its shell. Such personal names and accompanying customs situated an individual in the realm of clan history and symbolic meaning. Names and customs also reminded people of the cooperative nature of the clan in matters of ritual and marriage.

Other clan naming systems did not make reference to totems. Instead, the clan names were nicknames or references to a supposed character trait of the members, and these names were often derogatory. They were thus like the Cheyenne and Kiowa band names. The Crows had this kind of naming, with clans called Bad War Honors, Greasy-inside-the-mouth, Sore-lip Lodge, and Without-shooting-they-bring-game.

TABLE 4.1 Personal Names of the Omaha Elk Clan

| NAME | TRANSLATION | IMAGERY |

| Binç’tigthe | Sound of the elk’s voice, heard at a distance | |

| Bthonti’ | Smell comes | Scent borne by wind, discovering game |

| Çin’dedonpa | Blunt tail | Refers to elk |

| He’çithinke | Yellow horn sitting | Yellowish velvety skin on new antler growth of elk |

| Heçonton | Antler white standing | Towering antlers of an elk |

| Ku’kuwinxe | Turning round and round | Bewildered elk when surprised |

| Nonmon’montha | Foot action, walking with head thrown back | Peculiar manner in which the elk holds its head when walking |

| Nuga’xti | Real male | Refers to clan taboo against using meat or skin of male elk |

| Onponçka | White elk | |

| Xaga’monthin | Rough walking | Jagged outline of a herd of elk, their antlers rising like tree branches |

Source: Fletcher and La Flesche (1972).

FIGURE 4.3 Osage and Omaha boys’ haircuts according to clan. (1) Head and tall of an elk; (2) Head, tail, and horns of a buffalo; (3) Line of buffalo’s back as seen against the sky; (4) Head, tail, and body of a small bird; (5) Head, wings, and tall of an eagle; (6) Shell, head, feet, and tall of a turtle; (7) Head of a bear; (8) The four cardinal directions; (9) Shaggy side of a wolf; (10) Horns and tall of a buffalo; (11) Head and tall of a deer; (12) Head, tail, and growing horn knobs of a buffalo calf; (13) Reptile teeth; (14) Horns of buffalo

ASSOCIATIONS

All of the sub-tribal level social groups discussed so far are formed of people who recognize common kinship, and with the main purpose of expressing common kinship. Plains Indian cultures were also notable for the degree to which they developed non-kin social groups. Non-kin groups are technically called associations or sodalities, but they have also been referred to as medicine societies, dance clubs, military or soldier societies, and craft guilds and by other similar names depending on the shared interest of the group. The key feature of these units is that membership is voluntary, meaning that it is not predetermined by kinship as clan membership would be. “Non-kin” groups might in fact recruit relatives, but members are not automatically born into them and membership is theoretically open beyond kin ties. Voluntary groups are important because they provide the structure for social relations that reach across kinship lines—they unite non-relatives in common purposes for the good of all and counteract the tendency for kin groups to see themselves in competition with one another.

Since voluntary associations were formed around common interests of worship, work, and recreation, and those interests differed between men and women, the Plains associations were usually gender-specific, and men’s associations were frequently the more prominent in social affairs. The reason for forming a group was often a blend of civil and religious duty, fellowship, and fun.

Men’s Associations

Many of the men’s associations were mainly military in nature. Even though every man was a warrior in Plains societies, associations were formed to promote valiant behavior and coordinate the efforts of raiding and defense. They were elite fighting units that took a special role in battle, perhaps as scouts or shock troops. Some were pledged to unceasing combat or continual patrol of the tribal perimeter.

Within the association, the members could be further distinguished. Commonly the ordinary members carried a strait lance and the smaller number of officers a lance with a crooked end like an umbrella handle. Long trailing sashes worn around the neck or over one shoulder also marked these warriors, with different colors for each rank. The no-flight warrior would take a position on the front lines of battle and pin his sash to the ground with his lance, a promise to hold his ground until relieved by a comrade who could join him in the fray and pull the lance to release him. The bravery of association warriors was proclaimed in special songs, some of which were referred to as “death songs,” to be sung by a warrior as he faced his end while anchored to the ground. Following are some association songs, two from, respectively, the Teton Strong Heart and Fox societies and two from the Kiowa Koitsenko (Real Dogs); the Kiowa examples are death songs associated with nineteenth-century warriors Poor Buffalo and Satanta:

Friends

Whoever

Runs away

Shall not be admitted

The Fox

Whenever you propose to do anything

I consider myself foremost

But

A hard time

I am having

All brave men must die sometime,

The Koitsenko must die, too;

It is a great honor to die in battle.

No matter where my enemies destroy me,

Do not mourn me,

Because this is the end all great warriors face.

—(Boyd 1981:76, 119; Densmore 1918:322)

Contrary behavior was another widespread practice adopted by individuals or entire associations. To demonstrate their unusual lack of fear, contrary warriors engaged in all sorts of backwards and illogical behavior. In camp, they plunged their hands into boiling soup and complained how cold it was or danced in the opposite direction of everyone else. In battle, they forsook common sense in pursuing the enemy, and the orders they took had to be given in the reverse. The Heyoka (Thunder Dreamers) of the Oglalas were well-known contrary warriors who could be bold and reckless because their spirit helpers were the powerful Thunder Beings. Among the Comanches were individuals called pukutsi, meaning someone who is crazy or stubborn. The pukutsi went around camp intruding on people’s meals and singing at inappropriate times with the buffalo scrotum rattle he carried. He cried as the people did when mourning on a day when no one had died. Asked by an old woman to get her a buffalo skin, pukutsi came back with the skin of a Pawnee.

One day the camp was attacked by Osages. Somebody said to pukutsi, “that’s right—just sit there, don’t do anything!” So he got on his horse and went after the Osages and killed all except one … didn’t even have a bow, just a lance. He went to chase the last Osage, who was pretty far off. Somebody said, “That’s right—go get that last one.” He just reared back his horse, got off, and sat down. Those guys must have been real brave, though.

(Ralph Kosechata, quoted in Gelo 1983)

The heightened coordination found in the military associations made them the logical groups to turn to when force was needed to control behavior within the tribe. Because the associations drew members from many kin groups, they could enforce the rule of law without creating conditions in which one kin group was trying to dominate others, that is, the kind of situation that would lead to a continual blood feud. Thus, military associations were often the temporary police force during tribal encampments, hunts, and marches. This method of social control worked well because it was precisely during the warmer months, when large groups of people were congregated, that police were needed and the associations were meeting; during winter the people in general were spread far and wide and the associations disbanded.

The Sun Dance gatherings in early summer required a good deal of regulation. Inconsiderate behavior, friction, and jealousies were more likely to erupt at this time. Tribal leaders would appoint one or more associations to serve as police as long as the people were convened (and it is important to note that the association members only had this coercive power when temporarily approved). Which association was appointed varied by tribal tradition; there might be random selection, a regular rotation of police duty among the associations, or the same association always appointed for this job. When it came time for the large communal buffalo hunt associated with the dance, it was imperative that no one ventured out ahead of everyone else to begin hunting, otherwise the herds could be scared off. Association members could patrol to prevent premature hunting. Long marches undertaken as the larger bands migrated also required policing. People had to be urged to keep up and not wander away from the main party in order to ensure the progress and safety of the whole group.

Association members were empowered in various ways. Often they carried quirts made with leather lashes attached to heavy wooden handles. These whips were not only a symbol of their authority, but were actually used to keep people in line. They could break up disputes with force and obtain restitution for the party that they determined had been wronged. To subdue a troublemaker, they might destroy his tipi and drive off his horses, ensuring that he would have to spend the rest of the encampment time getting his belonging back together. In more difficult cases, they were allowed to beat the offender or even deliver capital punishment. People who otherwise cherished individual freedoms welcomed this measure of security during the large gatherings. The degree of force used by the association, however, was sometimes subject to controversy, and public opinion, delivered directly or through the commands of leaders, was always in play to influence the immediate and long-term behavior of the police.

Instances in which association members exceeded their authority are found, for example, in Cheyenne history. Some time in the mid-1830s the Cheyenne Bowstring Society members were eager to attack the Kiowas. They were instructed by the Keeper of the Sacred Arrows, a ritual leader with prophetic and advisory powers, not to go ahead with their plans. They disputed the Arrow Keeper’s authority and beat him with their whips before setting off on the raid. According to oral tradition, when the 40 or more society members then encountered the Kiowas, they were surrounded and all massacred, as if under a curse.

Around the same time Porcupine Bear, a leader of the Dog Soldiers, was banished from the Cheyennes for stabbing to death another tribesman in a drunken tussle. Soon he was joined by a number of relatives and friends, many of them fellow Dog Soldiers, forming a residential band separate from the tribe. This Dog Soldier band existed for several years and pursued its existence quite apart from the other Cheyennes. They attacked the Kiowas in a stunning raid avenging the Bowstring Society massacre, although according to some accounts their victory was not celebrated by the main tribe because they were exiles. Gradually, the Dog Soldiers gained strength, taking up their own territory east of the Cheyenne area and intermarrying with similarly militant Sioux factions; they even staged their own Sun Dance. They became especially aggressive in tormenting non-Indian traders and raiding trains and settlements. Often the U.S. troops punished the other Cheyenne bands for the raids of the Dog Soldiers. The emergent Dog Soldier nation was annihilated by the Fifth U.S. Cavalry at the battle of Summit Springs, Colorado, in July 1869.

The foregoing examples show what could happen when associations stepped beyond the normal bounds of club behavior. In the first case, there was believed to be a supernatural punishment. In the second case, an association evolved into something different: the temporary, seasonal warrior’s club evolved into a permanent military unit; it could also be said that the club became a band and, eventually, something approaching a distinct tribe. The balance between civic duty and military ambition could be fragile, and no doubt there were other unrecorded instances of association turmoil and transition in the earlier stages of Plains occupation.

Fellowship was also an important part of association life. Members often maintained their own lodge where they would retire to smoke, plan raids, and recite their war deeds. Even though the associations’ duties were often secular rather than religious, they had their own origin myths along with ceremonies meant to seek the aid of their spiritual founder and guardian and to transmit whatever special spiritual power their guardian bestowed between members. They owned special songs and dances, unique shields, pipes, or medicine bundles, and insignia that required blessings in cedar smoke and other sacred techniques. Club dances and rituals were occasions for the public display of the warriors’ ethos and accomplishments. There was a lot of good-natured teasing and practical joking in the association lodge as well. Common recreational activity during peacetime helped strengthen the bonds of friendship that unified the tribe.

Although the associations are described as voluntary and kinship was not the basis for belonging, membership was not totally random, but guided by social pressures. It was usually expected that a man would follow his father or older brothers in joining a particular club. Despite the risk of shame, young men were sometimes reluctant to join a no-flight society, and it is reported that among the Plains Apaches potential candidates often avoided camp during induction time and had to be rounded up and pretty much forced into serving.

A few tribes had age-graded associations. These associations were like the grades in school through which succeeding classes pass. While age grades are considered voluntary associations because they are not constrained by kin ties, age-grade eligibility was defined automatically, and in some tribes these groups were so important as to include virtually all males. Among the Arapahos, Blackfeet, Gros Ventres, Mandans, and Hidatsas, the clubs represented a sequence that a man would graduate through with his age-mates as their lives progressed. After some years in one club, the generational group would buy its way into the next-ranked society, to displace the elder group and be replaced by a younger one. The elders were addressed as “fathers” or “grandfathers” and they demanded ritual payments and a feast before they would turn over the sacred knowledge, dances, songs, and insignia of the club to the younger men. The oldest men, having passed through all six or so associations, “retired” from warrior life.

Among the Arapahos, graded men’s societies were known as lodges. Adolescent men joined the Kit-Fox Lodge together and proceeded through the Star, Tomahawk, Spear, Crazy, and Dog lodges. The Arapaho lodges were central to tribal integrity and highly ritualized. Each lodge involved elaborate initiations, special knowledge, ceremonies of prayer and sacrifice, and the bestowing of special honors or “degrees” with distinctive regalia. Younger men established mentorships with elders from the higher-order lodges. Women actually played an essential role in the system by receiving supernatural power from the elder mentors and transferring it to their husbands. Thus, Arapaho women were seen as progressing through the age grades along with their spouses.

More of the Plains tribes had ungraded associations. The Arikaras, Assiniboines, Cheyennes, Crows, Kiowas, Pawnees, and Sioux each had an array of unranked clubs that played a major part in tribal life. Virtually every man would belong to an association in these tribes. The Comanches, Sarsis, Shoshones, and Plains Crees also had ungraded societies, although they were less significant to the overall character of these tribes, at least during the periods for which we have information. Weak versions of military associations were also found among the Southern Siouans; in these tribes, strong clan and religious society structures took the place of military clubs in providing integration.

Membership in the ungraded clubs did not depend on age, although typically the core was formed of age-mates. And although the associations were not ranked chronologically, at any given time one or two might be more prominent in tribal affairs, and others moribund owing to war or disease fatalities. An association might disband for a time upon the death of one member, and occasionally a club was completely exterminated in battle and existed only “on paper” until an entire new membership could be established. In ungraded systems, there was sometimes a traditional competition between clubs to see who could accrue the most war honors. The competing clubs also played pranks on each other in camp. The Lumpwood and Foxes among the Crows had such a well-known rivalry. Retirement from the ungraded associations came with older age. Some offered a lifetime membership to elders, who continued as valued advisors, participating in club ceremonies and planning but not in combat.

Looking across the many plains tribes, whether they had graded or ungraded societies, there were only a limited number of club names in use. Most of the tribes had a Kit or Swift Fox society (named for small western fox species), and (Buffalo) Bulls, Wolves, Ravens (or Crow-Owners), and Dogs (with variations such as Crazy Dogs, Little Dogs, etc.) were also widespread names. Another name that shows up in various forms refers to a weapon: Tomahawks among the Arapahos; Stone Hammers and Lumpwoods among the Hidatsa and Crow tribes. The Kiowas and Kiowa Apaches each had a Rabbit Society that introduced boys and girls between age 5 and 12 to the customs of society dancing and regalia and groomed them for adult club life.

The Kit Foxes in one tribe resembled their namesakes in the other tribes, sharing special details of dress and ceremony, to the extent that there must have been a common origin of the Kit Fox idea that was transmitted or imitated across tribal boundaries. The sale or ceremonial transmission of associations between tribes is recorded in some cases. In some instances too an association present in an ancient parent tribe might have spread as that tribe subdivided into the tribes known historically. Whatever the commonalities, each tribe added its own peculiarities over time and incorporated the basic society concepts in novel ways. The Kit Foxes of the Hidatsas and Arapahos were young men, while the Piegan Kit Fox society was made up of older married men. Societies might spawn junior counterparts; this process probably accounts for the occasional presence of Dogs and Little Dogs in the same tribe. Moreover, through time the rank of a particular club could change within the age-grade system of a particular tribe, if the system were disrupted and reorganized. Thus, a list of Hidatsa clubs from 1833 shows the Dogs as the sixth of 10 age-ranked clubs, while a list pertaining to around 1870 had the Dogs as the ninth club in the Hidatsa scheme. Lists and descriptions of associations in particular tribes that are found in historical writings and tribal oral traditions must be regarded as dated snapshots of a continuous process.

Women’s Associations

Women also formed clubs around their interests, although these were not as prevalent or influential as those of men. One responsibility of adult women was to support the efforts of the male warriors in their families by providing material goods and comforts as well as the good wishes and spiritual protections that could be afforded by singing, dancing, and praying. An extension of these responsibilities across kin lines was achieved when women formed non-kin auxiliaries to the men’s warrior associations. One or more women of such a group might be selected to gather food and cook for the men’s club. On the night prior to the men’s departure for battle, the women sang and danced to ensure their success. “Among the Kiowa a man starting out on a raid was likely to appeal to a body of possibly forty Old Women whom he feasted on his return in gratitude for their prayers” (Lowie 1982:97). It was also their job to spread sand in preparing the ground for the Sun Dance. At least in modern recollection, the Comanches had similar women’s groups that supported men’s clubs such as the Crow Society. When the men came back from battle, the women donned the men’s headdresses, took up their lances, and danced with scalps hanging from the lance tips in a victory celebration.

Other women’s associations functioned ostensibly as craft guilds, although they promoted excellence in a wide range of female activities, such as midwifery. In these clubs, labor was combined to carry out intensive handwork in a helpful and friendly setting. Imagine all the hand stitching necessary to sew a watertight tipi cover of 14 buffalo hides, and it is easy to see the appeal of a group effort. A given project could be finished much more quickly, plus there was sharing of childcare and companionship all the while. Older women shared their expertise with younger ones, ensuring the continuance of techniques and gently enforcing “quality control.”

FIGURE 4.4 Two members of the Cheyenne Warriors Society Auxiliary, a modern women’s association, wearing the fringed shawls of the society at a powwow near Medicine Park, Oklahoma, 1982.

Among the Cheyennes there was a single women’s craft club, the Robe Quillers. Not a simple group of hobbyists, this club functioned as a true guild that owned the exclusive rights to the techniques of quillwork, the art of decorating clothes, bags, and tipi covers with dyed, woven, and sewn porcupine quills (a forerunner of decorative beadwork—see Chapter 6). The knowledge of quillwork was considered sacred, and it was practiced and imparted only in the most strictly ritualized ways. Every new decoration project was begun with a vow. Workers recited their past projects as if they were men proclaiming their great war deeds. If a novice was to be taught, she must first show respect by bringing food and materials for the club members. A camp crier announced the start of the new project, gifts were given away to celebrate it, and if a sewing mistake was made, an accomplished warrior would be summoned to cut away the bad part as if taking a scalp. Many of these ritual touches mirror those surrounding the pursuit of war honors by men; their use in relation to women’s work was a way of recognizing the serious and complementary nature of women’s contributions to tribal welfare.

Religious Societies

Although social life was infused with religion and all associations practiced some characteristic rituals, the main functions of the clubs were usually secular. There were, however, some non-kin associations with direct religious purposes. It is best to understand these societies as groups of medicine men and medicine women united in order to work their supernatural power collectively and to train novices, their successors in the next generation, in the ways of the spirits. People in these groups shared their knowledge and spirit power with each other and in effect sold or licensed it to younger people who aspired to follow them through often elaborate training rituals.

The line between military and religious societies is not entirely firm, since military club members typically shared some special ritual knowledge or supernatural power. Even outside the structure of the military clubs, power-sharing groups could form more or less spontaneously without turning into major tribal social units; the Comanches were known to have such short-lived cooperatives of power possessors. In the case of the Southern Siouans and Crows, however, religious societies became quite central.

Religious societies were the most important non-kin groups among the Southern Siouan tribes, and of the societies in these tribes, the Omaha Shell and Pebble societies are the best known. The Shell Society (Washisk’ka Athin, “shell-they have,” “shell owners”) was begun, according to tribal legend, by a mysterious stranger, actually a spirit from the animal world, who visited a worthy Omaha family and taught them the secrets of herbal medicines and magical powers, though taking the lives of the family’s four children in exchange. The children are taken to a great lake, where they are engulfed by waves, and the grieving parents are left only with shells as reminders. This legend, ripe with symbolism about death and renewal in both the animal and human worlds, outlined a procedure whereby a select group of Omahas, including both men and women (in replication of the genders of the legendary family), could continue to pass down the bestowed supernatural knowledge in a prolonged series of initiation rituals.

Membership in the Shell Society was sold to new acolytes of the succeeding generation, usually along family lines. The members possessed a large assortment of ritual items, including a drum, special moccasins and face-paint patterns, a special board for cutting ritual tobacco, and hide packs containing pipes along with sticks to be handed out as invitations. Accompanying these items were numerous songs referring to episodes of the origin story. Regular meetings were held in May, June, August, and September, signifying the respective mating times of the black bear, buffalo, elk, and deer. The dramatic apex of the rituals was the magical shooting of cowry shells into the novices, who feigned death and then, by coughing up the injected shells, rebirth—this capability attested to their mastery of supernatural power.

The Pebble Society used small translucent stones for the magical shooting but was otherwise similar to the Shell Society and may have been the older of the two. Whereas the Shell Society drew its members from chiefly families and emphasized group performances, the Pebble group recruited notable curers and focused more on doctoring. According to anthropologists such as Robert Lowie and Gloria Young, both were adaptations of a society prevalent among the Woodlands people to the northeast, the Grand Medicine Society (Midewiwin) of the Ojibwas, Sauk-Fox, and Winnebagos, which attests to the historical connection between the Southern Siouans and the Siouan peoples of the Great Lakes region (the great lake in the Shell Society legend is probably a reference to this connection). The Shell and Pebble societies have been referred to as secret societies because the knowledge transmitted was considered secret and the early segments of their rituals were closed to the public. However, the Omahas did not keep secret the identity of members with masks or totally private ceremonies, as is the practice in true secret societies in other cultures.

Religious observance was also the basis of a non-kin organization among the Crows called the Tobacco Society (bacu’sua, “soaking,” a reference to the technique for sprouting tobacco seeds). This group, made up of several chapters and involving men and women both, oversaw the cultivation of the tribal sacred tobacco crop. The tobacco species they planted was not the same one they used for smoking, but another, considered holy and signifying the tribal past as a horticultural people. Members observed a complicated regimen of singing, dancing, planting, and harvesting to ensure the well-being of the symbolic plant and, hence, the tribe. When the seasonal cycle was successfully completed, the tobacco itself was simply discarded in a ritual manner, by throwing it in a creek. The Crow Tobacco Society differed from the Omaha religious societies by focusing on gardening rather than animal power, but all were similar in their general intent to foster seasonal renewal and tribal welfare and in such details as initiation, special face-paint patterns, the selling of membership rights, and so on.

LEADERSHIP

Chiefs

Leaders of Plains Indian societies are normally referred to as chiefs, and this book will continue to use the term, but chief is very much like the word tribe in the conceptual problems it poses.

In some of the theoretical literature the term “chief” is reserved for the leader of a chiefdom, a specific kind of non-industrial society in which each individual member has a unique ranked position in relation to the top person, based on his or her kinship distance from that person. As the top person in the hierarchy, the chief is responsible for passing out the goods and services created by the group, but not everyone is treated equally. Here the leadership position is an inherited one, with a rule of succession placing a close kinsman of the chief in his office the moment he dies. Sometimes the chief is even thought of as a god on earth, which explains his privileged position. Societies in this proposed category are rare and transitional, standing in size and complexity between band and tribal societies, with their wide equality of members, and state societies, in which entire groups of people, rather than individuals, are ranked, forming castes or classes. Some societies that have been classified as chiefdoms include the Polynesians of the South Pacific islands and the prehistoric Mississippian Mound Builders of the southeast United States. No Plains Indian society had this kind of organization, however, and Plains “chiefs” should be called “headman,” the term used for band and tribal leaders, according to many of the theoretical schemes.

Whether the chief or headman name is applied on the Plains, it is more critical to understand the nature of the leadership role—how it was defined, what it was meant to do, how a person qualified for it. First, it must be noted that the role was variable. A careful look across the various Plains tribes through time shows that chiefs could have differing levels of responsibility, authority, and power. They might work alone or as members of a council. They might use physical force themselves, though usually they did not, and they might or might not get a military association to enforce their decisions.

It is also important to ask, in particular cases, whether the chief was fulfilling a role that was well defined and traditional in his own society or responding in an inventive way to new circumstances such as increasing trade or warfare, either with new Indian neighbors or with non-Indians. Non-Indians typically sought a single, authoritative leader with whom to do business and make treaties, even if such a strong figure was not normally part of the Native political structure. This approach could lead to non-Indian exaggeration of the degree of authority that was actually present, or else a new kind of leader might actually arise to meet non-Indian expectations. The early Spanish occupants of the Southern Plains, for example, thought in terms of their own military and civil patterns, and their reports refer to Native leaders as “generals” and “captains.” American treaty negotiators frequently insisted on dealing with a “principal chief,” even when no single leader had overarching authority from the Indian perspective. There is nothing less authentic about the non-traditional leadership roles—they result from very real circumstances—but they should be recognized as late developments in a dynamic process of adjustment to non-Indian influences.

One pattern that generally does hold true for the Plains was the distinction between military and civil authority; in other words, there were “war chiefs” and “peace chiefs.” War chiefs were men who had enough of a reputation as fighters that they could repeatedly come up with convincing plans for raids, muster other warriors, and lead them in combat. Among the tribal leaders, they tended to be the younger, openly ambitious men. In tribes with well-developed military associations, the most prominent war chiefs might be the officers of the associations. War chiefs gained stature by the number of successful raids they led and the deeds of valor they committed. Success meant ensuring the safety of one’s followers above all else, and not losing men in combat. It also meant returning with horses, captives, and other coveted goods. War booty was the property of the raid leader, but the good leader shared it freely with his followers, further enhancing his prestige and influence.

Except during times when a large part of a tribe was embattled, it was the peace chiefs who guided the day-to-day decision making. Peace chiefs were generally older but still vigorous men who had distinguished themselves as hunters and warriors but then wished to turn their efforts to domestic matters and the larger strategic issues of intertribal relations. In most tribes there was a clear distinction between war and peace chiefs, with different native terms for each, and it was necessary to abandon the first role for the second, although in some cases the difference has been overemphasized in non-Indian accounts, since Euro-Americans were liable to judge the purposes of Indian leaders categorically, while the formation of a leader’s public persona was actually fluid.

The job of peace chief required a special personality:

The personal requirements for a tribal chief, reiterated again and again by the Cheyennes, are an even-tempered good nature, energy, wisdom, kindliness, concern for the well-being of others, courage, generosity, and altruism. These traits express the epitome of the Cheyenne ideal personality. In specific behavior this means that a tribal chief gives constantly to the poor. “Whatever you ask of a chief, he gives it to you. If someone wants to borrow something of a chief, he gives it to that person outright.”

(Hoebel 1988:43)

Men with such qualities emerged frequently enough, and naturally. There were no campaigns or elections, nor were there rules of automatic succession. As the Comanche elder That’s It explained in 1933, “I hardly know how to tell about them. They never had much to do except to hold the band together …. We did not elect [peace chiefs]. We were not like you white people, who have to have an election every four years to see who is going to be your leader. A peace chief just got that way” (Wallace and Hoebel 1952:209, 211).

While That’s It’s comments are useful in helping us contrast Comanche practice with the modern world of political electioneering, they do belie the marked degree of talent and effort that was necessary for a man to gain and hold a position of leadership. Universally on the Plains, chiefs were expected to be effective orators. They were supposed to be able to think through the pros and cons of a situation and to deliver persuasive speeches that spurred the formation of public opinion and roused the people to worthwhile action. Much of this effort was directed at making peace between potential or actual disputants, intervening, and soliciting peer pressure, without physical force and before violence erupted. The key concern was prevention of a blood feud, in which relatives of one complainant harmed relatives of another in an unending cycle of revenge that would tear apart the entire band or tribe. Calming talk was the essential step in defusing such a situation. The role of chief as “good talker” is indicated, for example, by the Comanche title tekwawapi, tekwa referring to speech and wapi indicating an honored specialist.

To be effective, chiefs needed to maintain a commanding presence that would overcome doubt and shame those who were reluctant to do what was right for the group. Part of this demeanor was the ability not to reveal frustration over the kind of problems that bothered ordinary people. A chief would refuse the payments normally made to heal an insult or grievance, and even remained unperturbed upon hearing that his wife had run off with another man. “A dog has pissed on my tipi,” a Cheyenne chief would say disdainfully when informed of such a problem.

Behind these public manners would have to be a keen understanding of human nature, applied both to those in the band and to outsiders—members of other bands and tribes, traders, potential and real enemies. This enhanced social sense had to be coupled with unusually good knowledge of natural factors affecting the future of the group, such as the climate and animal behavior. To gain all this understanding, the chief paid close attention to past practices and their outcomes, learning through personal experience, but also from oral traditions passed down by the elders. Thus, the chief was likely to be an expert student of tribal history.

It was sometimes easy for people to detect the character and wisdom of a chief in his offspring. Also, they became accustomed to relying on all the family members of such a public figure for leadership. Therefore, while there were no actual rules of succession, there were many instances in which a man was followed by his son or nephew in the chief’s role, and sometimes the successor assumed the earlier chief’s name.

Another common figure was the chief’s assistant or camp crier who carried through with the chief’s responsibility of announcing news, decisions, and policies throughout the village. His horse clopping among the tipis, the crier rode through camp and heralded the next migration, hunt, or ceremony, the outcome of a chiefs’ meeting, or the approach of visitors. He would announce when lost objects had been found and return them to their owners. If a large council audience or greeting party was convened, it was up to the crier to arrange people in the proper order and positions. The crier was one of the few means by which a chief could extend his authority through the actions of another person. Among the Comanches, the herald could be referred to as tekwawapi , as a chief was. The Spanish found camp criers to be so prevalent among the Southern Plains tribes that they had their own words for them: tlataleros, derived from a Nahuatl (Aztec language) title, or pregoneros, Spanish for “proclaimers.”

Councils

Chiefs worked in concert with, and shared authority in varying degrees with, councils made up of the headmen of smaller-order bands. The council structure ensured broad representation. In the serene setting of a large tipi at night, council members met, smoked, and engaged in slow and careful deliberations. On a warm evening, they rolled up the bottom of the tipi and people gathered outside to listen to the discussions. Councilors observed rules of etiquette that ensured that every representative had a turn to speak, or at least a chance to decline. Elder men spoke first, followed by successively younger male speakers and, occasionally, women. The talk was respectful and centered on the issues, not on individuals. Every effort was made to reach a full consensus, even if a decision required many meetings.

Usual matters for discussion included when and where to move camp, when and where to stage major rituals, and whether an association should be appointed as temporary police. The council also deliberated on the evidence and punishment in cases of crime within the tribe— adultery and murder. If there was a need for unified tribal policy on joining an intertribal alliance, declaring war, or establishing trade relations, the council handled these issues also, which were distinct from the organization of raiding parties by individual war leaders. In some cases, the council might even overrule the plans of a revenge or horse-raiding party because of worry for the safety of the participants or concern about the risk that enemy retaliation would pose to the tribe in general. Council decisions were proclaimed throughout the village by the camp crier.

The council concept reached its most involved form in the Cheyenne Council of Forty-Four. This council of 44 peace chiefs was considered more important to the survival of the people than any of the military associations or individual chiefs. As if to emphasize this importance, the Council of Forty-Four was said to have originated in a mythic episode older than the origins of all other tribal rituals. The Council origin story, an adventure about a captive girl who bestows traditions to the tribe, has several aspects: it makes the council superior to the tribal military associations; it creates an injunction against murder within the tribe, and thus against the anarchy that would result from such an act; and, it foretells the coming of other characteristic Cheyenne myth and rituals, again placing the council in a primal position within tribal tradition.

The Council of Forty-Four was more formal than usual on the Plains in that the number of members was fixed, and the membership term was a standard 10 years. Members were inducted in a special ritual. Normally at least four representatives were selected from every band. In a population of about 4,000 Cheyennes, this rule ensured quite thorough representation. Council members who lived through their whole term chose their own successor from their band, and although the office was not hereditary, they frequently chose their own sons. Five councilors who had already served at least one term were selected to return as sacred chiefs—a supreme chief and four assistants. These figures were each associated with particular rituals, spirits, cardinal directions, and seating places in the council lodge, in a web of symbolism.

CRIME, LAW, AND DISPUTE SETTLEMENT

A common question of social theory in earlier times was whether societies that lacked strong political authority figures and an alphabetic writing system could have law and order. The answer is a resounding “yes” once the Plains tribes are considered. The question is rooted in assumptions about how legal principles are recorded and enforced, based on practices in complex nations. But the rule of law should already be evident in the previous discussions of chiefs, councils, associations, and the importance of public opinion in shaping behavior. Further evidence of Native legal concepts and methods of enforcement can be seen by looking at individual cases which have been preserved through oral tradition and personal memory and recorded by anthropologists. Case studies show that Plains societies had clear ideas about crime and punishment, as well as a systematic approach to settling disputes and wrongs by looking at past precedents and seeking remedies that had worked before.

Theft was almost never a problem in an Indian camp. All men and women had essentially the same ability to make or obtain the basic tools and possessions so there was little incentive to take someone else’s. A person who did feel the temptation to steal someone else’s bow, saddle, or horse would not be able to hide it for very long anyway. Also, it was often thought that items like shields and regalia were imbued with the character or the personal spiritual power of the owner, so that it was believed that a thief could face supernatural backlash from the item itself if it were stolen. And the giving away of belongings merely for the asking was considered ideal behavior, so when someone coveted another’s possession he or she could simply ask for it and expect to get it. Consequently, no one needed to lock their homes or guard their property from tribe mates. (The one exception to the rule about intratribal theft was occasional and concerned horses: there are some Kiowa cases, for example, in which the theft of horses was prosecuted. In these cases the misappropriation was an act of revenge or was excused as “confusion” about ownership.)

Problems did arise, however, in the area of interpersonal relations. There were jealousies and arguments, tempers sometimes flared, and violence sometimes erupted. Wife stealing and adultery were not unknown. If a husband mistreated his wife, he might find himself in a fight with his brothers-in-law. Unsuccessful marriages also could result in a demand for the return of bride wealth—the husband of a divorcing woman might insist on the return of horses that he had given her brothers to recognize the union. The use of sorcery to cause illness to an antagonist was normally a matter between individuals and families, but if it was thought that a person used medicine power for evil on a regular basis, the problem was recognized as one affecting the entire group, and corrective action was taken against the sorcerer. There were also cases of accidental homicide and murder. Frequently, particular instances of such troubles were related to each other. There was a need to determine right from wrong, to assess and collect damages, and sometimes, to exact corporal or capital punishment.

When a man felt he had been wronged, he gathered what evidence and witnesses he could and sought out the offender. It was best to obtain a confession if possible. An accused man might simply own up to the wrong publicly, either to end the bad feelings with a humble admission or to challenge his antagonist further by boasting. Among the Comanches, men forced confessions from women by taking them to a lonely place and choking or whipping them, or threatening them with fire. The charges and outcome of an adultery or sorcery dispute could also be placed in the hands of the supernatural by invoking a conditional curse. In the Comanche tabepekat (“sun-killing”) ritual, an accuser presented the charges to the sun, earth, and moon, and the defendant swore his or her innocence in the same way, proclaiming, for example, “May I die when the geese fly from the south to the north if I have done the thing that he has charged me with” (Hoebel 1940:99). All then simply awaited the outcome; in some cases, it was believed, the guilt was indeed confirmed with the premature death of the accused. But frequently no confession or supernatural sanction was available, especially when individual men went against other men, and then dispute settlement was a matter of whether the accuser could build group consensus in order to isolate the accused, or else physically intimidate or force the accused to make restitution.

It was not unusual for a person to feel too weak to bring his case against a powerful warrior. He then had the option of enlisting a champion who would do so for him, selecting someone who could match the accused in strength and reputation. The champion went to work solely for the prestige of it, and if he collected damages they went all to the victim. In an odd twist on this tactic, an old woman that no honorable man would fight was put forward as the mediator. In one Comanche example of this method, the victim in a wife-stealing case did not get his spouse back but did receive a horse-load of goods as damages. Wives who were accused by their husbands of unfaithfulness were subject to severe beatings or the not uncommon punishment of disfigurement, the man cutting off part of the woman’s nose and then disowning her.

Legal recourse in rape cases seems to have varied, if accounts are reliable. Several non-Indian observers have indicated that sexual relations were so free that unwanted advances were not a common social problem. One interpretation of these accounts might be that men acted with abandon and women had little power to bring formal complaints of rape, beyond attempting to drag a night-crawling assailant outside, calling attention to his misbehavior, and embarrassing him. The Cheyennes, however, for whom there is an unusually detailed record, and who placed a high premium on women’s chastity, punished even attempted rape severely by beating the offender nearly to death or destroying his property and killing his horses. If the violator was young, his parents might suffer the property destruction. In these cases it was normally the women relatives of the victim who meted justice. Women therefore had some legal protections beyond their brothers’ oversight of their marriage situation. When a Cheyenne girl disemboweled her father as he tried to assault her, she was acquitted of murder charges, because the incestuous rape was considered so odious. By attempting it her father had become less than Cheyenne, less than human, so his killing was not considered a murder.

Murder was the most serious offense because, apart from the sorrow it imposed on the victim’s family, it removed a needed person from the necessary work of survival and so posed a threat to the entire group. A murder also risked the beginning of a blood feud, a chain of revenge killings between the victim’s and murderer’s kin groups that could quickly disrupt normal work and take everyone, even bystanders, to the brink of starvation. Among the Cheyennes, the murderer was said to have the stink of death about him, as though his body were corrupting from within; this was a symbolic expression of his foul status. It would be said too that blood stained the feathers of the Sacred Arrows, an allusion that the murder was a blight on the entire tribe.

To help prevent blood feuds, banishment rather than execution was often the preferred punishment for murder. The offender was driven off for several years at least. Some refugees tried to be taken in by an alien tribe. Others struggled alone far from human company in a life of lonely hardship. Some eventually approached their former tribe laden with gifts and asked for forgiveness; if they appeared truly penitent and the memory and emotions of the crime had faded, they might be taken back. Though oral tradition records that some banished murderers were truly reformed, returnees had to tolerate stern warnings from the tribal council when readmitted and they remained stigmatized; some ritual act, like the reconsecration of sacred arrows or the bestowal of a peace pipe, was required as well. There were also cases in which a returned murderer killed again. In the one recorded Cheyenne case of a two-time killer, the murderer was executed in a clever ambush. The killer was shot dead by a kinsman of his two victims, wherein earlier he was summoned into the trap by members of his own military association. So while elements of blood feud were present, the non-kin association most closely responsible for the killer’s public comportment stepped in to engineer his elimination, as part of its responsibility to impart justice and smooth over kinship-based antagonisms.

Intensive study of Comanche cases showed that this society granted the kin of a murder victim the right to kill in just retaliation, and that a strong collective will about this right combined with relatively weak kinship obligations among tribe members ensured that the case would then be considered closed without further feuding.

EXAMPLES OF ORGANIZATION: THE CROWS AND COMANCHES

Now that the many factors in tribal organization have been outlined, we can see how they are realized by comparing two Plains societies, the Crows of the northern Plains and the Comanches of the south.

The Crows

All Crows spoke a single language which was of the Siouan language family and related to Hidatsa. Those with this shared tongue called themselves Absáalooke (also spelled Absiroke, etc.), meaning the children of a large-beaked bird resembling a crow or kite. Despite the common language, the Crows lived in three distinct groups. The River Crows lived along the Yellowstone River, maintained contact with the Upper Missouri village tribes to the east, and had adopted the Horse Dance of the Assiniboines. The Mountain Crows lived in the Wind River region and had ties with the Shoshones in that part of Wyoming. A late offshoot of the Mountain Crows composed a third group, called Kicked-in-their-Bellies. The literature on the Crows refers to these units as bands or divisions, though they were relatively large and probably deserving the latter name.

Across the entire population was a system of 13 exogamous matrilineal clans. The Crow word for clan, ashamamaléaxia, meant “as driftwood lodges,” a poetic image that likens the tightly woven social relations of the clan to a pile of tangled sticks found along a river. This metaphor of interconnection was also extended to other relations between people and between humans and the spirit world. The clans were grouped in pairs and threes to form nameless larger units for mutual aid, which anthropologists would call phratries. In general, clan membership dictated a person’s main line of allegiance. In a feud, for example, one was expected to take the side of one’s clansmen. In some matters, however, bilateral descent was recognized; this was the case for the inheritance of medicine bundles and the duties associated with them.

The Crows depended heavily on both military and religious associations to structure cooperation among non-kin. Their men’s military associations were ungraded, and through the 1800s they included Stone Hammers, Foxes, Lumpwoods, Little Dogs, Big Dogs, Muddy Hands, Half-Shaved Heads, Black Mouths, Crazy Dogs, Ravens, and Bulls. Throughout the century, some of these units combined or divided, and the Crazy Dogs was imported from the Hidatsas around 1875; indeed most all of the units seem derived from the graded system of the Crow’s Hidatsa relatives. The Lumpwoods and Foxes were the dominant clubs and they participated in a famous rivalry in which they competed to make the first strike against enemies and even kidnapped each other’s wives. One of the military clubs was appointed each summer to police the communal buffalo hunt, but there was no fixed rotation of service. We have also seen how the Tobacco Society functioned as a large non-kin religious order for both men and women. This group celebrated the common historic roots of the tribe as a gardening people related to the Hidatsas, by nurturing a purely representative strain of tobacco. Despite their key role in the Tobacco society and other rituals, and in the production of tipis, clothing, and baggage, Crow women apparently did not form craft guilds as women did in some other tribes, nor did they form war auxiliaries.