CHAPTER 8

ORAL TRADITIONS

Before the world, the South Wind, and the North Wind and the West Wind and the East Wind, dwelt together in the far north in the land of the ghosts. They were brothers. The North Wind was the oldest. He was always cold and stern. The West Wind was the next oldest. He was always strong and noisy. The East Wind was the middle in age and he was always cross and disagreeable. The South Wind was the next to the youngest and he was always pleasant. With them dwelt a little brother, the Whirlwind. He was always full of fun and frolic.…

—(anonymous Lakota storyteller; Walker 1983:183)

Despite now centuries of disruption, oral traditions have been one of the more enduring aspects of culture on the Plains. The continuation of tribal stories is closely interrelated with the survival of native language, and no doubt the traditions have been eroded through language loss, although many of the stories are still retold by tribe members in English along with or instead of those in the original language. Consequently, scholars are able to continue collecting and analyzing traditional stories for linguistic and cultural studies, adding to a body of recorded material that has been accumulating since the late 1700s. In recent years a number of tribes have put oral traditions at the center of their own preservation efforts because of their value in maintaining language, history, and cultural knowledge. Several tribes now have programs for collecting tribal stories from elders, publishing them, and placing them in local school curricula.

For many Indian people the perpetuation of tribal stories is a critical matter of self-definition and self-determination. Roger C. Echo-Hawk (Pawnee) has rightly noted how the distinction between “history” and “prehistory,” even as used in this volume, is an imposed non-Indian framework which suggests a strict divide between what is more or less knowable. But rather than thinking of their oral narratives as furnishing some less dependable vision of the remote past, Indians may see them as constituting their own authoritative ancient history, of equal value to the written records of non-Indian deep time (and a record which can and should be correlated with other records, such as those from archaeology). Indeed, many Indian storytellers regard their tales simply as history rather than, say, literature, art, religious doctrine, or folklore.

At least some non-Indian scholars have struggled with the historical value of Native oral traditions. The question of the retrieval of Native history has a long account on the Plains. As anthropologist Douglas Parks has pointed out (1996:1), anthropologist James Mooney’s Calendar History of the Kiowa Indians (Mooney 1979 [orig. 1898]) was the first full attempt to combine Native and non-Indian sources to construct an American Indian tribal history. Mooney worked from two series of Kiowa pictographs rendered on hide and paper (described in Chapter 6). Each pictograph was a reminder that prompted stories, to be delivered orally by the elders, and the sequence of pictures in these cases provided a chronological order and degree of consistency to the storytelling. Mooney was able to reconcile information about the past generated by the pictographs with information from other sources, both Indian and non-Indian, toward an even more robust account of Kiowa history. Not all Plains tribes encoded their histories in so-called “winter counts,” but all perpetuated a body of oral traditions that serves as a rich basis for understanding their past.

Notwithstanding the historical worth of Indians stories, they are also appreciated within and beyond Native cultures for their artistic qualities, as entertainment, and for their ability to condense and transmit life lessons, morals, and values. Indian narratives therefore may be regarded as oral literature as well as oral history.

Plains Indian stories conform to different types. Since the days of the German folklorists the Brothers Grimm, distinctions have been made between myths, legends, and folktales, and this typology captures some of the differences among Indian stories, though imperfectly. According to the folklorists’ definition, a myth is a narrative that deals with some major existential question such as how the world was made or where people go when they die. Myths include characters and actions that are outside of normal experience; they take place in a different dimension of time and space, and while fantastic and improbable, these stories are regarded as serious and true by those who perpetuate them. Because myths concern creation and fate and demand belief, they are associated with the sacred and religious ideology.

Legends, on the other hand, tell of actual persons and events that are believed to have taken place in ordinary time in the past, though they may include exaggerations and unlikely outcomes. Legendary characters may have started out as real historical persons, but their exploits have become magnified. Therefore, legends can sometimes verge on the serious concerns and fantastic dimensions of time and space addressed in myth. Legends encapsulate the heroic history of a group of people. Believability of legends is negotiated—the listener is not quite sure if every part of the legend is true but is willing to go along.

A folktale is accepted by everyone as imaginary. In European folktales, for example, the beginning phrase “Once upon a time” actually cues the listener that what follows never actually took place, but is a made-up story for entertainment and perhaps moral education.

Other types of narratives can be added to this basic scheme. Sometimes people just tell others what happened to them in the recent or distant past in a conversational way. Such stories can be called unpolished reminiscences. If they relate the same episode repeatedly they may standardize the way they deliver it, forming a kind of narrative called a memorate. These kinds of stories are also extremely important in preserving and transmitting tribal knowledge, but have not been as systematically recorded as myths, legends, and folktales. One can also imagine how a legend or myth could form over time from a memorate, as the story is repeated by others over generations and becomes imbued with significance, more communal, and more remote from the original occurrence. Perhaps in some instances too a story that once had mythic significance could lose its importance over time and survive only in a reduced, more casual form.

Tribes have their own schemes for classifying stories. The Oglala Sioux recognize two genres, ohunkanan, which they liken to myths and fables, and wicooyake, the telling of war adventures and local events that are deemed “true” in the sense that they are part of immediate human experience. Similarly, Arikara storytellers note two classes, naa’iikáWIš, which they translate as “fairy tales,” and “true stories” with no special native term. Both classes cover different kinds of stories, but generally Arikara fairy tales are stories about the trickster and other fanciful creatures, and true stories include those concerning mythic times, legends, historical and supernatural events, and the origins of ritual. The Comanches also use two different words to denote narratives. One, narumu?ipu, refers to any kind of narrative, while the other, narukuyunapu, is reserved, according to one storyteller, for “old time stories—some of it’s facts, it may be something somebody saw in a vision, things that the people used to know that might be forgotten” (quoted in Gelo 1994:302). (The element naru- in both these words means “exchange,” for that is how storytelling is conceived, and it is customary, though not mandatory, among the Comanches as among many Plains tribes for storytellers to receive small gifts in trade for their stories.) Each of these Native sets of categories, like the non-Indian distinction between myth and legend, grapples in its own way with the need to discern between the supernatural and everyday human domains.

Oral narratives have many essential qualities that can never be adequately captured by written transcription. Yet unfortunately so much of what remains of Plains Indian oral traditions is in the form of stories collected, printed, and reprinted over many years. And normally these stories have been saved in a form in which the native language has been translated freely into English. Free translations have varied greatly in quality, from those intent on making the story conform to English literary standards of grammar and plot sequence to those, more recently, rendered by literary scholars trained to be sensitive to Native forms and meanings. For expediency, the present discussion does rely on free translations and summaries to illustrate features of narrative. It must be recognized, however, that narratives in these forms are highly imperfect and often at best rough approximations of what was originally being said and meant.

One practice that helps address the deficiency of the printed form is interlinear translation. The translation lines can be inserted directly between the native text lines or gathered in a parallel paragraph. For example, the following story told by Comanche elder Emily Riddles in the 1950s is rendered as she spoke it in Comanche with a literal English translation in parallel, numbered so that each sentence and word are directly glossed (after Canonge 1958:31–33):

1. soobe?sukutsa?1 rua2 ahtakíi?3 tumuumi?anu4. 2.—ibu1 nu?2 tabe3 ikahpetu4 manakwuhu5 nana?atahpu6 naboori7 kwasu?i8 tumuukwatu? i 9, —meku10. 3. u1 pía?k u se?2,—tua3 unu4 o?ana5 manakw u 6 miasuwaitu? i 7,—me8 u9 niikwiiy u 10. 4. situk u se?1 ahtakíi2,—natsatsa3 taa4 nomia?eku5, u?ana6 esitsunu? i kat u 7, tahu8 na?numunuuka baik i 9 nu10 yutsumia?eek u 11.—5. situkuse?1 si?anetu2 yutsuhkw a 3 tumuumi?atsi4.6. situk u se?1 yutsiumi?aru2, yutsiumi?aru3, u4 biarupinoo? karuku5, uma6 karuhúpiitu7. 7. maa1 ma2 karukuk u se?3 piawosa?áa?ra?4 mawakatu5 to? i hú piitt u 6,—hina7 unu8?—me9 u10 niikwiiy u 11. 8. suruk u se?1—tsaa2 nu?3 naboori4 kwasu?i5 suwa ait u 6—me7 u8 niikwiyiy u 9. 9. situk u se?1 nana? atahputi2 tutuetupihta3 himan u 4 uma5 sihka6 esi?ahtamúu?a7 tu?ekan u 8. 10.—meeku1 nabuuni2 —mek u se?3 suru4 u5 niikwiiy u 6. 11. situk u se?1 si?ana2 wunur u 3, nabuihwun u bun i 4. 12.—nohi?1 tsaa2 nabuniyu3 nuu4—mek u se?5 suru6 esi?ahtamúu?7. 13.—usu?1 nu?2 buesu3 tsaa4 naboori5 nu6 suwainihti7 kwasu?utua? i 8 miaru? i 9 nu?10—usu?11 mek u se?12 suur u 13. 14. si?anet u kuse?1 suru2 pit u su3 yutsun u kw a 4, so?ana5 sehka6 esi? ahtamúu?a7 pukuhu8 sooyori? i kahtu9 pitun u 10. 15. suruuk u se?1 esi?ahtamúu?nuu2,—osu3 hak aru4 nan i suyake5 nabooru6 uku7 tamukaba8 kaht u 9—16. sumu?kuse?1,—uru2 u?3 rumuuko? i?4—me5 yukwiiy u 6. 17. suruk u se?1 pumi2 urii3 nasuyakeku4, punihku5 uhka6 pu7 nara?uraku? i ha8 urii9 tu? a wekun u 10. 18. setuk u se?1 esi?ah tamúu?2 sebutu3 tabe?ikahpetutu4 sumuyorin u kw a 5, tsu?n i kat u 6, setu7 sumukoyaman u 8, nanan i suyake9, setu10 naboohk a 11. 19. suk u 1 sehka2 naboori3 ahtamúu?a4 naahkaku5, atanaiht u 6 uruuku7 bitun u 8. 20. suruk u se?1,—munu2 esi?ahtamúu? nuu3 hakanihku4 nanan i suyakeku5 naboohk a 6?—me7 urii8 niikwiiy u 9. 21. suruuk u se?1,—tumuuy ukaru2 nun u 3 usu4 sube?su5 suhka6 esi?ahtamúu? a7 tumuuko?ikat a 8 nihán u 9, tsaa10 naboori11 u12 kwasu? u tumuuhk a 13—me14 yukwit u 15. 22. subet u 1.

1. Long ago1, it is said2, a grasshopper3 went to buy4. 2.—I2 will go to buy9 (a) different kind of6 designed7 coat8 (I will go) far away5 this way1 towards (the) going down4 (of the) sun3,—(he) said10. 3. His1 mother2 said to8 10 him9,—You4 continually3 want to go7 over there5 far away6.—4. This1 grasshopper2 (said),—No matter3? When5 we4 move5, when11 I10 fly11 among9 our8 relatives9, there6 (I) appear grey7.—5. This one1 at this place2 flew off3, / going/ to buy4. 6. This one1 goes flying2, goes flying3, where that big rock hill sits 4 5, (it) stopped and sat7 on it6. 7. As3 he2 sat3 on it1, (a) big grasshopper4 climbed6 towards him5 and stopped6,—W hat7 (do) you8 (want)?—(he) said to9 11 him10. 8. That one1 said to7 9 him8—I3 want6 (a) nice2 designed4 coat5.—9. This one1 took4 different kinds of2 little stones3 with it5 [them] (he) painted8 this6 grey grasshopper7. 10.—NOW1 look at yourself2,—that one4 said to3 6 him5. 11. This one1 stands3 here2 looking at himself much4. 12.—I4 look3 very1 nice2,—said5 that6 grasshopper7. 13.—Already3 I2 received8 that1 nice4 designed5 coat8 (the) way I want6 7. I10 will go9,—thus11 said12 that one13. 14. At this place1 that one2 flew /off4/ back3; (and) arrived10 there5 (at the) place8 (where) those various6 grasshoppers7 are flying a lot /to9/. 15. Those1 grasshoppers2 (said),—Who4 (is) that3, (who) looks6 pretty5, (who) here7 among us8 /is/ sitting9?—16. One1 said5 6,—It3 (is) that one2, returned from buying4.—17. As4 they3 wished for4 that2, that one1 told10 them9 in that way5 [how] he7 met8 that one6. 18. These various1 grsshoppers2 all flew off5 (in) various ways3 towards the going down (of the) sun4 (and they) stay6 (and when) these various ones7 all returned8, these various ones10 are designed11 pretty9. 19. As5 those various2 designed3 grasshoppers4 are living5 there1, one from a different kind6 came up8 to them7. 20. That one1 said to7 9 them8,—How is it4 all you2 grey grasshoppers3 are designed6 pretty5?—21. Those ones1 are saying14 15,—We3 shopped around2. Thus4 at that time5 when13 he12 bought13 the nice10 designed11 coat13 (someone) named9 that6 grey grasshopper7 “Is Returned from Buying8.”—22. That is all1.

Stories reproduced this way are more laborious to read than simple translations but provide a much richer sense of what is being communicated. First of all, a record of the Native voice is established, and even someone not conversant with the native language can see the vocabulary and grammar (word order), and thus gets some sense of pacing, vocal quality, and the nuances of meaning. In this case the conversational pace is highlighted by the transcriber using dashes to set off alternating quotations. Several narrative devices, in this case ones that are customary in Comanche storytelling, are also evident. The aforementioned quotations are important because Comanche stories, and indeed all Plains stories, rely heavily on character dialogue, even expressing the thoughts of characters as statements from them. There is very purposeful use of the pronouns “this” and “that” and the word “here” to distinguish between the first grasshopper and the other grasshopper he meets, making the main character and his experience more immediate to the listener. Repetition of words (Sentence 5, “goes flying, goes flying”) is a common way of emphasizing extended or continuous action in Comanche, and Comanche storytellers use this device whether telling stories in Comanche or English. This practice may also be related to the Comanche linguistic trait of reduplicating initial sounds in motion verbs for emphasis. Here the teller creates a sense of significant distance by repeating the reference to flight.

The decisive moment for the adventurous grasshopper takes place as he sits on a “big rock hill”; such allusions to high landmarks as points of revelation are a common element in Comanche stories. Also notable are the opening and closing formula phrases, “Long ago, it is said …” and “That is all,” which again are customary in Comanche storytelling. These are somewhat similar to the phrases “Once upon a time” and “happily ever after” in English fairytales in that they serve to mark off the story from other kinds of verbalization and cue the listener. The phrase “it is said” also places the narrator in a remote position with respect to the occurrences she is about to relate, in effect declaring “this is something I heard about, not saw directly,” which is the common subject position for Indian storytellers.

Beyond these structural characteristics, it must be understood that a storyteller and listeners bring all manner of linguistic and cultural associations to the story by which they process its meaning, and which are not apparent to someone outside the culture. The Comanche story makes more sense if one knows that there is a great variety of grasshoppers found on the open plains of Comanche country (over 100 species) and that many of these types when viewed close up display distinguishing body features and colors, sometimes vivid markings arranged in marvelous geometric patterns. Although interesting in and of itself, the variation of grasshoppers may have been of special concern because in the past Comanches ate grasshoppers as an emergency food. But aside from this factor, variations in natural forms are important in teaching young people to be observant of their surroundings, a common concern in storytelling. In the story above, the main character is introduced as ahtakíi?, a generic grasshopper term reducible to “horn,” in reference to the insect’s horny face, and probably-kíi is an onomatopoeia element. The big grasshopper that he meets is a different kind, piawosa?áa?ra?. This name refers to a very large green variety and literally means “big suitcase uncle,” after the notion that it wears large saddlebags or parfleches. Further along, the main character is called esi?ahtamúu?a, a more specific term for a grayish grasshopper, literally, “gray horny nose.” This plain grasshopper is then transformed in the story into another recognized variety, the multicolored tumuuko?ikatu, “is returned from buying,” also called tumuuko?i?, “to buy” or “to trade.” In the traditional Comanche frame of reference, colorful textiles for clothing are acquired through trade. So the tale is in part a just-so story about the origin of one colorful variety of grasshopper. Listeners might know that the kinds of grasshoppers mentioned exist within an even larger semantic field that includes the red ekawi, the yellow óhawi, the pásia with yellow thighs, and the kwasituna, a type with a straight tail.

There is even more cultural significance in this story, however. The little grasshopper goes on a long, intentional journey to a hill to find what he is looking for. Hill landmarks such as Quitaque in Texas were used by the Comanches as the meeting places for trade with other tribes and the Comanchero merchants who brought colorful cloth from New Mexico. Moreover, the word for the “big rock hill” used in this story, biarupinoo, is also used as a proper noun in Comanche to name the sacred cliffs called Medicine Bluffs north of Lawton, Oklahoma, where people went on vision quests; so there is some suggestion of the supernatural in the grasshopper’s adventure. This meaning is heightened by other details. The grasshopper flies toward the sun to obtain his colors. Throughout the Uto-Aztecan world (Comanche is a language in this family), the bright colors of flowers, birds, and insects are regarded as manifestations of the power of the shining sun. A sacred complement to this formula is the medicine power of the earth, as represented in mineral paints such as red and yellow ochre applied to the body, and indeed the little grasshopper is anointed by the big one with earthen paint (“different kinds of little stones”). Also inherent in the story are more general notions about the importance of trading and the value of beauty and personal adornment; and there is allusion to how personal names are best acquired—through notable deeds and adventures. Thus, the story touches on several aspects of Comanche natural history, religion, and social custom, and in doing so it teaches cultural knowledge in a way that is appealing to listeners, especially children. All this is not to say that a teller or listeners always have all of these significances in mind, but they are embedded there and perpetuated nonetheless.

Another aspect of narratives not easily captured in written form is the manner in which they are delivered and received. The performance of narratives as a communicative act involving the teller and audience is an important consideration in understanding their meaning and functions. On the Plains, performance practices are fairly standardized. Usually stories are told by one or more of the elders to a grouping of people. It is best not to tell them off the cuff, but always when the time and setting feel appropriate. It is a universal belief among the Plains tribes that traditional stories are supposed to be told during the winter and preferably after dark. This rule is especially applicable to myths, since stories having to do with the correct order of the cosmos must reflect the concern for order in the manner of their telling.

When a reason is given for this belief, it is usually said that winter evenings were when families were gathered for safety and warmth around the fireplace and had the leisure time away from buffalo hunting and related chores. It is often said that telling stories out of season can invite supernatural punishment; a summertime story might cause the sudden appearance of a dangerous snake. That the hearth is the idealized setting for storytelling further shows how the transmission of tribal knowledge is perceived to be a serious social duty nested in the family and kin group.

The techniques of oral narrative delivery are also typically not captured in written form, but in reading texts one should imagine how the storyteller uses body posture, gestures, tone of voice, abrupt shifts to signal dialogue, and sound effects to enhance the dramatic quality of the stories. The continuous reactions and responsive commentary interjected by listeners are also part of the total experience.

Another common belief among Indian storytellers is that they should not tell the same tale more than once in a season. This belief stems from the notion that the tales, myths in particular, are part of a long cycle of related stories that describe the continuing adventures of the main characters, and which should be delivered in sequence so as to complete the cycle. Viewed together, one can see that certain individual narratives can form a sequence. Often, however, in practice it is not possible or practical for storytellers and their listeners to complete a cycle, owing to time constraints, the mobility of individuals, incomplete story inventories among some storytellers, and the nature of the stories themselves. Particularly because parts of stories are recombined in various ways in a natural process of variation as they are heard and repeated within and between generations, a “correct” sequence of stories can become obscured or unimportant. In other instances story cycles are maintained with a strong commitment and respectful attitude.

The modular quality of oral narratives has led to the classification of narrative motifs. A motif can be any element that recurs across stories: a character, kind of character, object, action, concept, or structural feature of narrative. In the Comanche story given above, some of the motifs are the young adventurer, the mother, the journey of discovery, the anointing with earth pigments, and the visionary experience in a high place (which functions both as a location and plot apex). Such elements can be found in many other stories. Although Native storytellers typically do not think in terms of motifs when generating or discussing stories, the concept of motif has been useful to those studying a society’s narratives from the outside, and for cross-cultural comparisons. Folklorists have given names and numbers to motifs and compiled them, most comprehensively in the Motif-Index of Folk-Literature (Thompson 1955–1958). A similar but distinguishable concept to motif is that of type, which refers to recurring overall plots. The story types that occur across North America and often beyond have also been named and indexed for comparative purposes. Some of the common story types found on the Plains include:

The Eye-Juggler (coyote induces another animal to juggle its eyeballs, and they get stuck in a tree, blinding the animal; or, coyote imitates the stunt and blinds himself)

The Star Husband (a girl looks longingly at a beautiful star and climbs heavenward on a rope to marry it; often used to explain the origin of the Pleiades or another constellation)

The Earth-Diver (during a primordial flood a series of animals is dispatched to dive for mud; one succeeds and thereby establishes solid land)

The Release of the Wild Animals (an ogress imprisons all the buffalos underground and a team of animals takes turns trying to release them, the last—the smallest one or the culture hero—successfully) (see Chapter 3)

The Poor Boy (a small, poor boy who lives on the outskirts of camp with his grandmother perseveres and, sometimes with the help of miraculous powers, triumphs in war and wins the hand of a chief’s beautiful daughter)

The Deserted Children (children playing carelessly off at a distance are left behind by their camp; they encounter a malevolent old woman or ogre whose clutches they escape with tricks, magic, and the help of friendly animals)

How these themes are fleshed out with variations of detail and plot twists can vary tremendously, yielding quite different narratives even among storytellers within the same tribe. (Indeed, there can be huge disagreement among tribe members about what is correct or admissible within their local tradition). The variations are themselves fascinating. Storytellers modify, substitute, and recombine motifs and tale types to create versions that in their minds are more entertaining, or more congruent with the specific natural and cultural environments of their tribe. Sometimes storytellers make changes on a whim or to add their personal flourish, or because they are not remembering exactly the story as they told it before or heard it from someone else. These changes have no larger intentional meaning. Other times, their changes are purposeful adjustments that reflect local notions about such matters as the economic and symbolic value of particular animals, how kinship and social relations are conceived, and how the supernatural world operates. Although it is possible to read too much significance into the differences, the study of oral narrative variations has stimulated much theorizing. Anthropologists, notably the French structuralist Claude Levi-Strauss (1908–2009), have drawn broad conclusions about how the human mind functions, and proposed regional and tribal cultural patterns, on the basis of the substitutions and inversions that have been introduced as tales were retold throughout South and North America, including the Plains.

Such transformation can be seen at work in the following four versions of the Deserted Children story:

Version I: All the children of a camp are off playing. One man proposes that the adults abandon the children by moving camp, and they do so. The oldest girl leads the children in a search to find the camp. They are taken in by an old woman who is actually a ghost. She kills all but the youngest girl and her little brother, who promise to work for her fetching wood and water. The girl brings a series of different kinds of wood and water, and the old woman is only satisfied with the kind of twigs known as “ghost ropes” and stagnant water. The children escape by feigning that they are just going outside; the girl leaves an awl in the ground as they get away which answers for them when the old woman calls after them. They come to a large river where a horned water monster demands to be loused. The boy louses him. The “lice” are frogs. The girl cracks a plum seed on her necklace four times to make the monster think that her brother has cracked a louse. The monster gives them a ride across the river. The old woman follows in pursuit. She refuses to louse the monster and he drowns and eats her. The children find the people who deserted them. Their parents and other relatives all deny knowing them. One man proposes that the children be tied and left hanging from a tree. A sick dog from the camp lingers behind and releases them. The children and dog find buffalos which the boy kills by gazing at them. They live prosperously. The girl dresses a pile of buffalo skins by sitting on them. She makes a tipi which is magically furnished. The dog becomes an old man. They find antelopes which the boy kills by gazing at them. Four bears arrive to guard their property. Their former campmates, now starving, attempt to rejoin them, and are driven away by the bears. The girl and her brother take spouses from the group, then the brother strikes the rest dead with his gaze.

(Gros Ventre; after Kroeber 1907:102–105)

Version II: While playing away from camp, two children, a brother and sister, call the chief an ugly name as he passes near. He directs the camp to move and abandon them. The children, forlorn, search for the camp and finally catch up. Their parents deny ever knowing them. The chief ties the children up and they are left to starve as he leads the camp to move again. An old dog releases the children. They find buffalos which the boy kills by gazing at them. The girl processes the meat and skins by sitting on them. They live prosperously and grow up. Their former campmates, now starving, attempt to rejoin them. The children deny ever knowing their parents.

(Arapaho; after Dorsey and Kroeber 1998:293–294)

Version III: Four children playing by a creek are joined by on older girl with a baby on her back. In the meantime their camp moves away without the children noticing. A succession of three of the children reports to the others that the camp has moved, but only the third is believed. They attempt to follow the camp’s trail. Coyote comes along to warn them not to disturb the owl. As they pass the owl’s house the baby cries and the owl hears him. The owl summons all the children and (implicitly) holds them captive with the intention of eating them. They escape by feigning to go to the creek to wash. As they get away they appeal to a frog for help, who answers for them when the owl calls after them. The owl comes upon the frog and attempts to kill him with his cane, but the frog jumps into the water, leaving the owl standing on the bank. The owl pursues the children. The children come upon a big creek and appeal to a fish-crane for help. The crane makes the oldest girl hold a louse in her mouth and bridges the creek with its leg, allowing the children to cross. The owl appeals to the crane for help crossing and is subject to the same condition, but the owl spits out the louse in mid-stream and falls into the creek. The owl, brandishing a stone club, continues pursuing the children and finds them on an open prairie. The children appeal to a buffalo calf for protection. As the owl approaches with its maul, the buffalo-calf charges him. The calf charges the owl and butts him up to the moon, where he can still be seen.

(Comanche; after St. Clair and Lowie 1909:275–276)

Version IV: Three children, a girl and her younger brother and sister, are mistreated and run away from home. They meet an old woman who is a child-eating ogress, and are invited to her tipi. The elder girl is aware of the danger and stays awake all night to guard her siblings. In the morning the children escape by feigning to go to a stream to fetch water. At the stream they appeal to a frog for help, who answers for them when the ogress calls after them. This explains the croaking of frogs. The ogress finally realizes the deception (and implicitly pursues the children). The children run to another stream and meet a crane. The crane lays down her neck for them to cross, but also does the same for the pursuing ogress. The children next come upon three buffaloes—a bull, cow, and a little red calf, whom they appeal to for protection. The cow and bull in turn charge the ogress but are killed. The calf charges the ogress and butts her up to the moon, where she can still be seen.

(Comanche; after Kardiner 1945:69)

In each example the main theme is child abandonment, but this arguably primal human worry is treated differently in each instance. In Version I children are purposely abandoned; in Version II, it is specifically done because they insult a chief. In Version III they are left behind accidentally, and in Version IV they are runaways. It seems that in the Gros Ventre and Arapaho tales the lesson is that parents should not be cruel, but in the Comanche versions the lesson is to children, not to play carelessly or run away. The number of children varies from an entire village’s worth to a brother–sister pair. The older girl or sister, an important Plains social role (see Chapter 5), is a prominent character in Versions I, III, and IV, but not II. Only in Version I are any of the children killed, and in this case the protagonists are quickly reduced to a brother–sister pair. Versions I and II are different from the Comanche versions in that the parents are punished, by death in I and by rejection in II. Actually, Version I combines two episodes, the magic flight related in Versions III and IV followed by the mutual rejection of parents and children seen in Version II. Coyote makes an appearance only in Version III; perhaps he is relatable in a structural sense to the dog in Versions I and II. There are magical sequences in Version I (types of wood and water) and Version IV (the three buffalo defenders) analogous to the “three wishes” common in European fairy tales. The crossing of streams is important in all versions but varies in detail. The motif of the louse occurs in the Gros Ventre and also one (but not both) of the Comanche versions, though in Version I the “lice” turn out to be frogs. The Comanche versions also have frogs, although here the frog makes its call to deceive the villain while the children escape, while in Gros Ventre it is an (animate) awl that aids the escape. In the Comanche versions live buffalos protect the children; in the Gros Ventre and Arapaho tales the buffalos are killed (give their lives) for food and shelter. The villains and their fates are similar but distinct in each telling. This dizzying list is only a partial accounting of the substitutions and inversions at work across the four versions, and this discussion will stop short of proposing specific tribal meanings for these variations, and just make the point that types and motifs are grist for a lively, endless process of narrative reinvention.

Meanings come alive most vividly through the personalities and activities of story characters. Chief among the character motifs is the one known to folklorists as the “trickster.” Trickster figures are found in tales throughout the world but play a pronounced role in American Indian storytelling. This character is one who wanders aimlessly from one situation to another causing mischief for those he encounters. His hunger, bodily functions, and lechery are unbounded and uncontrolled. Many of the stories therefore include ridiculous scatological and bawdy situations which most tribes find acceptable and amusing, though non-Indians might consider them obscene. The trickster is selfish and ill-tempered; he has no conscience and seldom shows remorse. Often his tricks backfire.

In some tribal traditions the trickster never reforms, and listeners learn their lessons about bad behavior through the trickster’s ongoing misfortune. In other traditions, as the trickster moves through a series of adventures he learns from his mistakes and becomes better behaved, more socially adept, and more humanlike. By following the trickster’s conversion, listeners learn what is improper and proper behavior, and the origins of the etiquette and morals that make people social beings—human.

On the Plains, the trickster usually appears in animal guise, either as a spider, such as the Lakota Inktomi and Omaha Iktinike, or as a coyote; and he interacts with other animals. In rare instances spider and coyote even appear together as competing tricksters. Both the spider and the coyote are perceived of as having inherent trickster qualities. The spider appears knowing and clever in the way it hides underground, spins webs, and floats on invisible silk. Able to move easily among the lower, middle, and upper worlds, it exhibits potential as a sacred creature. Coyotes are notorious for their apparent cleverness and opportunism. Some Comanche names for the coyote highlight these traits: káawosa (“trick sack”); káarena’pï? (“tricky man”); isapu (“liar”); tukuwa?ra (“food grabs”). Despite its unflattering reputation, the coyote earns attention as a potentially sacred creature because of its kinship with a noble sacred animal, the wolf. In the Algonquian northeast the trickster is a rabbit, and so it is among the Plains Crees and Plains Ojibwas; the rabbit also appears as an alternative to the spider sometimes in Lakota, Osage, and Omaha stories. The Plains Crees also feature another northern incarnation of the trickster named Wi-sak-a-chak (often Anglicized as Whiskey Jack), who is modeled on the Canada jay, another species thought to be mischievous.

Iktiniki meets Coyote on a walk. Coyote tells him of a dead horse he has found and suggests that they both drag it to Coyote’s house to eat. Coyote ties Iktiniki’s hands to the horse’s tail and urges him to pull. But the horse is not dead; it stampedes and drags Iktiniki though the thorn bushes. Coyote laughs at his trick. Iktiniki plots his revenge and waits until winter. He takes Coyote out on a frozen lake and instructs him to put his tail through a hole in the ice to catch a fish. When the tail freezes in place, Coyote thinks he has caught a big fish. They both pull until they tear Coyote’s tail off.

(Omaha; after Erdoes and Ortiz 1998:112–114)

Coyote is starving and goes along a creek bank. He repeatedly sees his reflection in the water and, thinking it is another coyote also trying to find food, becomes angry. He charges the “other” coyote and drowns because he cannot swim.

(Arikara; after Parks 1996:366)

Rabbit boasts to Squirrel that he can do anything with Buffalo. To prove it, he rides Buffalo to Squirrel’s tree. He pretends to be sick so Buffalo will give him a ride. Rabbit saddles Buffalo, decorates him with a bell and feather, and whips him. As they approach Squirrel, Rabbit boasts, “See what I told you,” and with that the Buffalo bucks and kicks, and the Rabbit jumps into the bush, with Buffalo chasing after him.

(Osage; after Dorsey 1904:9)

Wi-sak-a-chak eats many berries though the berries warn him that they will cause flatulence. Wi-sak-a-chak then goes hunting, but he breaks wind and scares the game and becomes angry at his anus. He burns his rump by sitting on hot stones. He comes upon a hill, and, too sore to climb, he walks around it instead. He walks in a circle thinking he is on someone else’s trail. He finds a scab from his rump and thinks it is dried meat that his grandmother has lost. Hungry, he eats it. A little bird tells him he is eating himself but Wi-sak-a-chak calls him a liar.

(Plains Cree; after Dusenberry 1962:148–149)

While tricksters most frequently appear as animals, they are often described in ambiguous terms as animal-humans, because the stories involve their transformation from wild to social beings; or, they are described as fully human. Ambiguity may be expressed in phrases such as “Coyote was a man who …” and the appellation Old Man Coyote. As a human character, the trickster appears again as Inktomi (Sioux) and with such other names as Nihansan (Arapaho) or Nixant (Gros Ventre), Sitconski (Assiniboine), Saynday (Kiowa), Veeho (Cheyenne), and Old Man Napi (Blackfoot). The last two are sometimes explicitly associated with white men, reflecting a cultural stereotype that white people are deceitful.

Inktomi thinks only of copulating. He pursues a beautiful young girl. The girl is annoyed and complains to Inktomi’s wife. They agree to change places. The young girl invites Inktomi to her tipi where his wife is waiting. In the darkness he believes he is making love to the girl and compares her to his old wife. In the morning he discovers who he is with. His wife beats him with a club.

(Lakota; after Erdoes and Ortiz 1998:123–125)

Inktomi marries at the age of 14 despite his parents’ advice that he is too young. Before he moves in with his wife, his parents warn him that it would be wrong to speak directly or make love to his mother-in-law. But Inktomi lusts after his widowed mother-in-law and seduces her in an elaborate pretense.

(Lakota; Erdoes and Ortiz 1998:128–131)

Nihansan asks for the power to send his eyes up into a tree. He does not obey the directions not to repeat the trick more than four times. His eyes do not return and he is blinded. He asks a mole for his eyes and the mole agrees. Nihansan finds his own eyes and places them in their sockets again, and throws away the mole’s eyes. That is why the mole is blind.

(Arapaho; after Dorsey and Kroeber 1998:51–52)

Veeho encounters a man with strange powers. The man is able to command stones and turn them over without touching them. Veeho begs the man for his power, and the man takes pity on him and decides to give it to him with the condition that he use the power no more than four times. Veeho displays the power four times to gain respect among his people. The people hail him as a chief, and he marries a chief’s beautiful daughter. He forgets the injunction and tries to impress the people a fifth time. A big rock chases him down and traps him. He appeals in turn to a buffalo, bear, and moose to release him but they are not able. He then tells an eagle that the rock has insulted him, and the enraged eagle breaks the rock, releasing Veeho. Veeho goes home bruised and broken, and his wife decides to leave him and declares him a fool.

(Northern Cheyenne; after Erdoes and Ortiz 1998:139–141)

Two other character motifs that often merge with each other and the trickster role are “creator” and “culture hero.” The creator is the agent whose miraculous activity results in the universe as we know it: through a series of adventures and interactions with other characters, he differentiates life from death, day from night, summer from winter, humans from animals, and he imbues people and animals with their notable characteristics; and, he may make the mountains, rivers, stars, and so forth. The culture hero is similar in establishing particular tribal traditions, such as mourning customs, ceremonies, dances, languages, and social divisions, by negotiating with other characters, performing miracles, and mentoring humans.

Old Man Coyote is cold. With a team of animal accomplices, and by a sequence of tricks, Coyote steals summer from the Old Woman who possesses it. The Old Woman’s children pursue and finally catch Coyote. Coyote refuses to give back summer and the children threaten to make war on him. Coyote proposes to share summer with them for half the year, and each accepts winter for the other half.

(Crow; after Erdoes and Ortiz 1998:13–15)

Saynday meets a (female) red ant. In those days the ant was round like a ball. He reduces his size to match hers. They debate the pros and cons of people dying. Saynday wishes that dead people should be reborn in four days; Ant argues that the world would get too full, and that dead people are tired and should be allowed to stay dead. Saynday gives in to Ant’s preference but warns her that she will have to live with the decision and mourn. Four days later Saynday finds the ant in the same place and she is sobbing. A buffalo has stepped on her boy and killed him. She begins cutting herself in two. Saynday stops her before she cuts off her head completely. Saynday then proclaims that from now on, when Kiowa women mourn, they should cut themselves but not kill themselves in sorrow.

(Kiowa; after Marriott and Rachlin 1968:223–225)

Besides the tricksters there are any number of animal characters who interact in tales, ranging from bear and bison to rabbit and prairie dog to turkey, quail, and chickadee. Rabbits, distinct from the Algonquian trickster figure, are also part of this cast. Normally these characters reflect some natural qualities of the animal. The bear and chickadee both figure in stories about seasonality, the former because of its habit of hibernating and the latter because it appears in numbers at the turn of the seasons, and because this bird has an unusual barbed tongue, and the number of barbs is thought to vary with passing months. The quail is often named Scares People on account of its habit of flushing suddenly from cover.

Often the animals who endure Coyote’s antics are species that live and find safety in “communities” (prairie dog towns, quail coveys), and their social and timid nature contrasts with Coyote’s solitary, selfish, and predatory ways; not to mention these animals are the natural prey of natural coyotes. They are also normally wary animals, and they fall victim to the coyote’s tricks only when they let down their guard. These weaklings nevertheless often manage to turn the tables on their attacker. But just as the trickster is sometimes human, so may be his victims. There are plenty of tales in which he deals with people instead of animals. In some tales from the nineteenth century or later, Coyote plays his pranks on white cowboys, soldiers, and preachers. In these tales, the trickster’s chicanery becomes a Native defense against the supposed greater immorality of non-Indians. Coyote always triumphs in these stories.

Coyote commands Turkey to go to his house to be cooked by his wife. But when Turkey arrives at Coyote’s house he tells the wife that Coyote sent him to copulate with her, and she complies. When Coyote gets home he realizes that Turkey had played a trick on him. Coyote sets out to kill Turkey. He fails at this task, and when he returns home, Coyote finds that his neglected family has starved to death. Whenever a coyote howls it is said he is crying over the death of his wife and children.

(Wichita; Dorsey 1995:289–290)

Coyote comes upon Rabbit with a leather pouch on his back. Coyote is curious and guesses that Rabbit has tobacco in the pouch. Rabbit tells Coyote that he has nothing that Coyote might want. But Coyote just thinks that Rabbit is being stingy. Insistent and then angry, he tears open the pouch. Lots of fleas are released and they infest Coyote. He runs off howling. This is why coyotes howl.

(Lakota; after Erdoes and Ortiz 1998:50–51).

A white man has heard about Coyote’s trickery. He puts on fine cloths, mounts a good horse, and seeks Coyote, challenging him to cheat him right before his eyes. Coyote says he must go get his stuff for scheming. He borrows the man’s horse, as well as his clothes so the horse will not be afraid of him. Coyote then gallops away, declaring “I have fooled you already.”

(Comanche; after St. Clair and Lowie 1909:276)

The cast of animal and human characters may also appear in sundry combinations without the presence of the trickster. The resultant stories can be similar to, or derivative of, trickster tales in their structure and the way they explain origins or teach lessons about correct behavior. Others are simply stories about minor adventures. Sometimes they have been labeled “fables” because of their animal actors and moral purpose. The tale of the grasshopper given above is one example of an animal tale without trickster.

Skunk and Opossum live together as sisters-in-law. Skunk proposes that they each eat their young. Opossum eats her young first. Skunk then proposes that they separate, and takes her young away. Skunk boasts that now only she has her young. Opossum becomes mad and defecates in Skunk’s face and kills her.

(Osage; after Dorsey 1904:11)

A little boy steals a toy wagon when he and his mother go to a spring. He tries to conceal it from her. She makes him bring it back to the place he found it in the dark, scaring him, and tells him why he should not steal.

(Comanche; after Canonge 1958:81–84).

Four men returning from a war party come upon a big lake. They watch a panther and alligator battle in the water, killing each other.

(Comanche; after Canonge 1958:93–94)

A class of myths that stands apart from the trickster cycle involves semi-deities, often female, who figure as alternate culture heroes in the origins of tribes and tribal customs. The Lakotas say that White Buffalo Calf Woman visited the people for four days and bestowed their seven major ceremonies. The character Corn (Silk) Woman or the similar Reed Woman appear in Mandan, Arikara, Omaha, and Sioux tales, as a spirit patron of horticulture. The Sioux explain Anukite (Double-Face, Double Woman, Two Face) either as a man who can change into a woman or as a beautiful woman who was punished for infidelity with a second, ugly face. She also appears as a duo of spirit women representing alternate answers in divination. In dreams they inspire women to quillwork and tanning, or they inspire cross-gender behaviors among women and men (see Chapter 5). Various human old women and beautiful daughters are also standard characters, and along with the female spirits they evoke life stages and the presence or absence of fecundity, and signify the fundamental importance of women in survival, procreation, and social life.

A young man goes hunting and finds a big buffalo. But there is nothing for him to hide behind in order to approach the game. Each morning he finds the buffalo again, facing a different cardinal direction, and each time fails to take a shot. One morning the buffalo is gone, and a strange plant is sprouting where it stood. He brings the holy men to see the plants. They decide to fence off the plants, discover at midsummer it is growing ears, and they learn to cook and eat the ears. They learn to plant the corn and grow more. A holy man is inspired to think of the ear of corn as a woman and instructs his wife to make a dress for it. She dresses the ear of corn, addresses it as mother, and sends it floating away in the river. Sometime later the woman arrives among them again and is recognized as Mother Corn, a counterpart of the Creator who helps people on earth.

(Arikara; after Parks 1996:153–156)

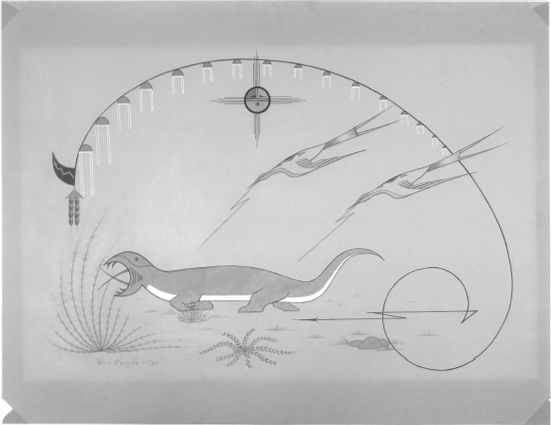

Seemingly animate aspects of nature, including the sun, moon, stars, clouds, and winds, as well inanimate objects like mountains, stones, and even household items like the awl in the Deserted Children story given above, may serve as narrative characters. There are dwarves, giants, and monsters described by modern people as resembling dinosaurs and great snapping turtles. The standardized Plains water monster, like the one in the Deserted Children story, is a long saurian with horns. Its nemesis is the thunderbird, whose cry is thunder and eye flashes, lightning. A man with a sharpened leg is able to jump and stick himself in the trees. There are ogres, including the owl in the Deserted Children story, which some modern storytellers liken to the legendary Bigfoot; a blood clot that turns into a boy; a one-eyed bounding human head or skull; and an animated ball of pounded meat that bounces here and there.

Meatball lopes along a road and comes upon Coyote lying in wait. Coyote professes to be starving and meatball offers him a bite of himself. Coyote moves ahead down the road repeatedly and secures more bites this way. The fourth time, meatball sees the meat between Coyote’s teeth and realizes he is being tricked by the same Coyote. Then Coyote runs away.

(Comanche; after Canonge 1958:21–23)

Plains legends, those stories situated in human time and space, have their own stock roles. The idea of the scout venturing forth in advance of his band to discover wonders is very common. Scouts are often able to become invisible in order to eavesdrop on talking buffalos or secretly witness the arrival of the first white men. Scouts exemplify the bold adventurous spirit that is the ideal for horse nomads. One version of this character among the Comanches is aptly named Sokoweki, “Land Seeker.” In contrast to this adventurer are the contrary characters, braves who never leave their tipis. Another legendary figure is the poor, unpopular, sometimes deformed orphan boy, who though diminutive rises to the occasion in some tribal emergency and surprises everyone with his skill, bravery, and supernatural power. Little Brown Boy is the name given to this character in some Comanche stories; he is known as Wets the Bed among the Wichitas, Burnt Belly among the Pawnees, and Bloody Hands among the Arikaras. Little Brown Boy teaches about self-initiative and class mobility. Among the Upper Missouri tribes, many stories feature the Two Men, holy men who are also stars. Yet another figure of legend is the Scalped Man, the ghost of a scalped warrior who terrorizes the living.

Perhaps because so much significance can be invested in these memorable characters, Indian storytelling does not require elaborate plots, character development, or tidy story lines in which there is a clear outcome. For even though it is recognized that many of the stories that have been collected are fragmentary, still, Native stories need not conform to the structural expectations of non-Indian oral or written literature. Often trickster tales relate a sequence of interactions between coyote and other animals with no strong climax or resolution.

The lack of certain formal conventions may strike non-Indian listeners and readers as unusual. But such tales are understood as segments of a long ongoing series of situations (which are not only told in story form but then also explored further in conversation about the stories), and therefore they are regarded as meaningful and satisfying. And, there are some stories that do have a definable structure of tension and resolution. There is also a tolerance for internal contradictions. In many tribal stories of the origination of the universe, the creator interacts with other beings who somehow already exist. The trickster character is especially capable of logically impossible activities. He can shift shape (an ability that supports the theme of personal transformation), or he is dismembered or dies, only to reassemble or resurrect himself within the same story or in a subsequent one.

Returning at last to the initial question of the historical value of oral narratives, we can see how some stories would provide very fanciful explanations of remote times. Thus, there are tales like the Plains Cree account of Wi-sak-a-chak’s creating hills in Southern Alberta by sliding on his buttocks, the Comanche story in which the thunderbird crashed and produced a canyon in West Texas, and the myths of many tribes concerning the origins of the butte known as Bear’s Lodge or Devils (sic) Tower in Wyoming. But the presence of these myths should not obscure the fact that Indian people also pass down stories about past events which are devoid of miraculous elements and which sometimes match very closely or exceed in precision the records produced by non-Indians. A host of stories from various tribes have been collected which relate genealogies, migrations, the fusion and fission of subtribal units, legal cases concerning murder and adultery, famous raids and battles, peace negotiations, descriptions of celebrated leaders, and other matters worth remembering. Many of these narratives are still in circulation in Indian communities today, and together they amount to a priceless resource for understanding the American past.

Apart from narratives there are other, briefer modes of traditional oral expression, though these have not been heavily documented on the Plains. Prayers appear to have been recited in standardized forms to the extent that several have been collected and presented as oral literature, as in this Omaha example:

Wa-kon’da [Great Spirit]

here needy he stands

and I am he

(Fletcher 1995:26)

Song texts along with prayers like this one make up a rich body of Native poetry. Additional examples of prayers and songs are given elsewhere in this book in context.

Joking has always played a part in maintaining cordial social relations and easing stress, and the capacity of Indian people for humor and wit is often noted. Older traditional humor mostly relies on riddles—enigmas posed for solution—or wordplay, or conundrums, which are riddles in which the solution depends on wordplay. Indian riddles often take a simple form, not involving wit or convoluted logic so much as just testing the listener’s memory about local folk sayings or conventions. The oddest of these, from a non-Indian perspective, is the question “What am I thinking of?” which is common as a game throughout Native North America. Other riddles have standard answers:

There is a place cut up by gullies. What is it? (an old woman’s face)

(Omaha; J. Dorsey 1884:334)

What is it that for one day has its own way? (a prairie fire)

(Comanche; McAllester 1964:254)

What is inside you like lightning? (meanness)

(Comanche; Ibid.:255)

What makes a cottonwood tree grow out of the top of your head? (telling a lie)

(Comanche; Ibid.)

Riddles sometimes appear as knowledge tests within myths or in ceremonies that promote healing or coax the arrival of summer. For example, in an Arapaho tale Blood Clot Boy defeats the evil White Owl in a riddle contest:

What is the most useful thing? (the eyes)

Tell me what you live on mostly (buffalo meat)

… tell me who are the parties who never get tired of motioning to come (the eyelids)

(Dorsey and Kroeber 1998:306–307)

Closely related to these riddles are proverbs, terse sayings encapsulating some valued truth. The Omahas would say, “He is like an animal,” meaning “he is obstinate,” or “The raccoon wet his head,” a figure of speech meaning that someone talks softly and smoothly when trying to persuade (Dorsey 1884:334). In Comanche to say “saddle the horses” is similar to using the English expression “go for broke,” “go all-out,” or “no holds barred” (Gelo 1983:7). Simile and metaphor are also employed, as in the Comanche phrase “long as a wolf’s yawn,” said of something taking too long, or the word ekapabi (vulture; literally “red head”) for “penis” (McAllester 1964:257).

Nowadays Indian people tell jokes with Native themes principally in English and in forms that are familiar to Euro-Americans. The emcees at powwow arenas are a handy source for modern Indian jokes. As they manage the dancing and other activities, they punctuate their spoken directions with rehearsed jokes and improvised humorous asides. Their jokes and quips depend on wordplay in English and Indian languages, parody of non-Indian culture, and the stereotypes and dilemmas of modern Native American identity (Gelo 1999:52, 55):

These two Indians were driving along, and they see a loose pig. They look around, you know, then they grab that pig and put it between them in the front seat and put a hat and some sunglasses on it. Pretty soon they get stopped by the highway patrol. “Have you seen a loose pig?” “No.” “Okay, go ahead.” After the pickup drives off, one cop says to the other, “What do you suppose that pretty white woman was doing with those two ugly Indians?”

This man who was a real good dancer died. His best friend, who was a good singer, mourned and mourned. Then one day, the dead man visits his friend. “I’ve got good news. Heaven is wonderful. Every week they have a big powwow.” His friend says, “That is wonderful!” A powwow every week?” The ghost says, “Yeah, but the bad news is, you’re the head singer next week.”

Custer wear arrow shirt.

These kinds of jokes are in circulation throughout Indian communities and they are merely collected and recirculated at public events. In their joking patter, powwow emcees ridicule themselves, jest with people in the audience, and touch on topics that are not normally appropriate in polite or ethnically mixed company. In this way they test the boundaries of proper behavior and serve something like the trickster of traditional narrative.

Native oral traditions are likely to remain alive on the Plains as long as their social and cultural contexts remain relevant. As people tell and listen to the old stories today, they align their lives with the intentions of the spirits and the wisdom of the ancestors. In the next two chapters we will examine how the world established in myth by Coyote and Corn Woman, and sustained by legendary scouts and warriors, is renewed again and again by ordinary humans, through their personal and collective rituals.

Sources: Beckwith (1930, 1937); Bowers (1991); Brunvand (1968); Buller (1983); Canonge (1958); Deloria (2006); G. Dorsey (1904, 1995); Dorsey and Kroeber (1998); J. Dorsey 1884; Dusenberry (1962); Echo-Hawk (1997, 2000); Erdoes and Ortiz (1984, 1998); Fletcher (1995); Frey (1995); Gelo (1986, 1994, 1999); Kardiner (1945); Kroeber (1907); Lévi-Strauss (1990a, 1990b); Marriott and Rachlin (1968); McAllester (1964); Mooney (1979); Parks (1996); Powers (1977); Schoen and Armagost (1992); Skinner (1916); St. Clair and Lowie (1909); Thompson (1955–1958); and Walker (1983).

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Oral traditions are one of the more enduring aspects of Plains Indian culture. The preservation of traditional stories has been a keen interest for Indians and non-Indians too. Such stories record history in the absence of written records, entertain, and encode cultural values. Non-Indians have used the categories myth, legend, and folktale to classify Indian stories. These categories correspond roughly to Native distinctions between stories as primarily mythical or historical. The translation of traditional narratives is always imperfect, although interlinear translation is a fairly thorough method. Storytellers and their audiences apply a host of meanings and interpretations to stories which are grounded in their native language and customs, but not always apparent to outsiders. Also, written translations are inadequate for capturing the performance of storytelling. Storytellers commonly recombine narrative elements. Folklorists have named the recurring motifs and plots to classify stories as they reappear through time and across many tribes. The trickster, an amorphous animal-human whose adventures define cultural norms, is a prominent Plains story character. Besides trickster tales, there are stories about the creation of the universe and tales that celebrate the exploits of historical figures, often in exaggerated form. The memories perpetuated through narrative are a valuable and often dependable source of historical information. Prayers, riddles, proverbs, and wordplay are additional lively forms of Indian oral tradition.

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. Explain the relationship between traditional narratives and history as it has been understood by both Indians and non-Indians.

2. Name and define some of the common story types found on the Plains.

3. Using the “Deserted Children” story type as an example, explain how stories can vary in form and meaning as they are told in different tribes.

4. Discuss the trickster character type. What forms does it take on the Plains? What cultural concerns are explored in stories about the trickster?