THIRTEEN

Yale May Not Think So, but It’ll Be Just Jolly

Aged fifty-five and into a fifth career, Van Vechten was as excited as a schoolboy when his first photographic exhibition opened to the public in New York in November 1935. “Im [sic] in a big show at Radio City,” he informed Langston Hughes, “and here is my first notice!” He had enclosed for Hughes’s attention a short review of the exhibition by Henry McBride, whose kind words about Van Vechten’s work may not have been entirely unbiased; he and Van Vechten had been friends for twenty years, and both were apostles of Gertrude Stein. Still, Van Vechten regarded public praise from McBride as confirmation of his inestimable talent. The exhibition displayed an eclectic mix of Van Vechten’s most celebrated subjects, hinting at the outline of his experience of the century so far, from Theodore Dreiser, to Fania Marinoff, to Ethel Waters and Bricktop, the African-American woman who ran the most fashionable nightclub in Paris during the 1920s. McBride’s verdict was brief but unequivocal: “literature’s loss is photography’s gain.”

Over the following years Van Vechten’s stature as a portrait photographer grew enormously, as did his skill. He gained the respect and admiration of many fellow photographers, including Man Ray, who was so pleased with shots that Van Vechten took of him and Salvador Dalí that he asked for permission to use them to promote his work. The praise that most pleased Van Vechten came from Alfred Stieglitz, who, along with his wife, Georgia O’Keeffe, sat for him on numerous occasions over seven years. “They are damn swell, a joy,” Stieglitz told him about one set of prints. “You are certainly a photographer. There are but few.” More and more great names ascended to Apartment 7D at 150 West Fifty-fifth Street and, from the fall of 1936, to the Van Vechtens’ two subsequent homes on Central Park West, to have their pictures taken. In February 1936, a year before her death, Bessie Smith returned to the scene of her infamous outburst eight years earlier to pose, this time on her best behavior, “cold sober and in a quiet reflective mood.” “I got nearer her real personality than I ever had before, and the photographs, perhaps, are the only adequate record of her true appearance and manner that exist.” Given that this was the only time that Van Vechten had met her while both were sober, quite how he would have known who the true Bessie Smith was is up for debate. However, his immodesty does nothing to alter that the portraits he took were among his best, and they immortalized in photographic form the same woman generations have discovered in Smith’s recordings: an artist who is alive, bright, and playful in some; reflective, pained, and soulful in others.

Bessie Smith, 1936, photograph by Carl Van Vechten

Not long after, he photographed Scott Fitzgerald, though not at his studio. “I hadn’t planned to meet Scott,” he told a biographer of Zelda’s when relaying how the two had accidentally met at the Algonquin one afternoon. Fitzgerald was at a table with the literary critic Edmund Wilson, but at first Van Vechten did not recognize Fitzgerald and stood waiting to be introduced. “It was a terrible moment; Scott was completely changed. He looked pale and haggard. I was awfully embarrassed.” After lunch Van Vechten shepherded Fitzgerald outside to take his photo. “He posed for two or three,” he explained, “and that was the last time I saw him.” Those impromptu shots are among the definitive images of Fitzgerald. Had things turned out differently, had Fitzgerald flourished after the twenties, perhaps Van Vechten’s photographs would not be known at all. As it is, Fitzgerald looks strangely uncomfortable before the lens, smiling but ever so slightly stooped and squinting in the sunlight and perfectly reflecting the faded glamour that he has come to symbolize.

Those close to him saw something different in the photographs. Some years later the Fitzgeralds’ daughter, Scottie, wrote to thank Van Vechten for sending her a print of one of the photographs, the best ever taken of her father, she thought, which captures “a nice sober, serious look … his hard-working side,” which she remembered much more clearly than his hedonistic tendencies. Scottie would have dearly loved for Van Vechten to have captured her mother in that same way, but he never heard from Zelda again save for a couple of odd, rambling missives she sent after her mental health problems had overwhelmed her. Just eight days after Scott’s death, in December 1940, she scribbled Carl a letter in pencil, betraying a fragile and distressed woman who bore no resemblance to the exuberant flapper Van Vechten had known in New York and Hollywood. She thanked Van Vechten for some kind words that he had written about Scott, and reflected on their shared experiences of the 1920s, “the glamour, and tragedy, of those courageous and dramatic lives so many years ago.”

It was the sort of maudlin reflection with which he had become all too familiar. In June 1938 James Weldon Johnson was killed in a car accident. Van Vechten was heartbroken at the news, one of the rare occasions when the death of somebody he knew caused him genuine distress. During the fourteen years they had known each other, they had fostered not just a close friendship but an intellectual kinship that for both of them symbolized the hope of a new era in which black and white Americans would eliminate the divisions of racial difference through social contact, the two races uniting over a shared love of art and entertainment, socializing together in apartments and nightclubs, forging friendships over drinks and love affairs on the dance floor. The two men celebrated their shared birthday together every year along with Alfred Knopf, Jr., who had also been born on June 17. Langston Hughes remembered the last birthday party they had, in 1937, at Van Vechten’s apartment. Presented to the three guests of honor were three cakes, “one red, one white, and one blue,” as Hughes recalled, “the colors of our flag. They honored a Gentile, a Negro, and a Jew—friends and fellow Americans.”

Sadly, Van Vechten realized that he and his great friend were never able to stand as equals in the eyes of wider society and that Johnson’s talents had been smothered by racial prejudice. “I always said, if he had been white he would have been ambassador to St. James in London,” Van Vechten stated. “He was a very tactful, diplomatic, extraordinary man, very delightful company, very amusing.” When he tried to express his feelings for Johnson as a man and a totem for the African-American cause, the only fitting way he could do it was to compare him with Charles Van Vechten, his own father. Both men had gifts that Van Vechten admired immensely: kindness, generosity, and conviviality, but most especially an ability to be both “tolerant of unorthodox behavior in others” and “patriarchal in offering good advice.” The comparison reveals that beneath his carefully managed image of the sophisticated iconoclast Van Vechten’s moral exemplars were his parents, whose bold stand on race relations kick-started his interest in African-American culture. Of course his parents, like his brother, Ralph, and his dear friend Avery Hopwood were long dead. When Johnson joined them, Van Vechten felt the presence of his own mortality and decided that now was the time to shape a concrete legacy for himself and to honor Johnson’s memory.

The first step Van Vechten took was to convene the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Committee. Featuring, among others, Walter White, W.E.B. DuBois, and Eleanor Roosevelt, for three years the committee attempted to create a public monument in tribute to Johnson: a bronze statue of a black man by the black sculptor Richmond Barthé placed at the entrance to Central Park on West 110th Street and Seventh Avenue. Barthé’s design, enthusiastically supported by the committee, had the man, who was a representative figure, rather than a depiction of Johnson himself, naked and shackled to celebrate the efforts of African-American artists whose work projects the beauty and humanity of their race in the face of discrimination and oppression. The project never materialized, partly because of the timidity of the city authorities, who feared the proposed design could be incendiary, and partly because of Van Vechten’s impatience with the politics of the situation and his refusal to sanitize the memorial by unshackling the statue or putting it in a pair of pants, as was requested. Van Vechten was frustrated with the processes of compromise and amelioration that committee work involved and equally vexed that there were those who seemed not to recognize that Johnson was a unique man who deserved a unique tribute. He guarded Johnson’s memory with jealous fervor, as if it were his own possession. One of the reasons his opinion of Walter White soured so much in later life may have been that White had replaced Johnson as the national secretary of the NAACP in 1931 and ran the organization with tremendous success for twenty-four years, his presence in the national consciousness outstripping Johnson’s, a fact Van Vechten seemed to resent. “Walter was never, in my mind, anything like as big a man as James Weldon Johnson was,” he said in an interview after both men had died.

With the plan for the statue dead and buried by 1941, Van Vechten moved on to something less striking but equally radical. For nearly the past twenty years, the collecting passion that was first fired in his childhood had been focused primarily on African-American materials. In boxes, drawers, chests, and cabinets and crammed onto the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves that wrapped around his apartment he compiled a huge depository of books, records, music scores, and manuscripts by and about African-Americans as well as thousands of items of correspondence with black artists, writers, performers, educators, and public figures. This stockpile of materials was so large he fancied it would make an excellent founding contribution to an archival collection dedicated entirely to the culture of black Americans. Yale University accepted his proposal to house the collection and so became the first Ivy League institution to hold any resource of that kind. It was named the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of Negro Arts and Letters, founded by Carl Van Vechten. Besides this being a fitting tribute to his friend, the name locked Johnson’s memory to his for time immemorial. Van Vechten also openly admitted that the use of Johnson’s name first and his second was “to induce others to make valuable additions to the collection.” He knew that the words “Carl Van Vechten” still caused icy chills in some parts of black America, and he suspected that eliciting first editions, letters, and other precious materials from prominent black figures would be vastly easier if it were done in the name of an African-American pioneer rather than the white author of Nigger Heaven.

Van Vechten’s plan for the collection was for it to be a vivid, living record of black culture. Throughout the 1940s, and for the rest of his life, he sought out valuable material wherever he could, entreating authors to gift draft manuscripts and inscribed first editions, along with letters that would shine a light on the intimate connections among and within black American communities. Langston Hughes joked that now he was to be absorbed into the august archives of an Ivy League college Van Vechten should expect his letters to acquire a new tone “and no doubt verge toward the grandiloquent.” “Don’t be selfconscious about Yale,” Van Vechten replied. “Henry Miller puts more shits and fucks and cunts in than ever when I assure him his letters are destined for college halls.” Beyond the joke there was a serious message. This was not to be an airbrushed record of the Negro edited by the white establishment; it was to be the unexpurgated story of a people in the words, sounds, and images of their highest achievers. To ensure that the great swath of African-American talent was represented, Van Vechten made it his mission to photograph every interesting and prominent black person he could entice to his studio and sent the results to Yale. As the years passed, the old guard of the Harlem Renaissance was joined on the rolls of Van Vechten’s film by a younger generation, including the likes of Eartha Kitt, Harry Belafonte, and James Earl Jones. And though Sidney Poitier and a few others declined invitations to pose—probably the lingering association of Nigger Heaven’s putting them off—the opportunity to be immortalized in the James Weldon Johnson Collection was irresistible to most. Even W.E.B. DuBois agreed to put past hostilities to one side and submit to Van Vechten’s lens, smiling warmly as he did so.

At the same time he was helping Yale amass its vast record of black culture, Van Vechten arranged for Fisk University, a small, historically African-American liberal arts college, to begin a collection detailing the history of American music, named the George Gershwin Memorial Collection of Music and Musical Literature, in honor of another recently departed veteran of the glory days, Gershwin having passed away in 1937. Again, the core collection was provided by Van Vechten himself from the piles of material that he had hoarded over the decades, all of which crowded the large, high-ceilinged rooms of his apartment. Having already donated the African-American materials to an Ivy League college in New England, he carefully calculated the choice of a black college in Tennessee at a time when Jim Crow laws were still very much in force. While the Gershwin collection “was all white people’s music for a Negro college,” he recalled some years after both collections had been established, “if you want to study the Negro since 1900, you have to go to Yale … I thought this would interest people of the other race to go and look up things in their respective places.” To his friend Arna Bontemps he admitted that the means were as important as the ends: “I am mad over the idea of breaking down segregation” by drawing white researchers into the archives of black universities.

Sitting on committees for grand civic projects and establishing formidable educational resources to strike a blow for racial equality, Van Vechten looked as though he had turned into his father. Certainly there were striking similarities, principally that both devoted themselves to projects that stressed the importance of individual self-improvement. But Carl’s ambitions had an aesthetic dimension that Charles’s never had. Creating beautiful surroundings was a passion of his that flowed irresistibly through his works as well as his private life. With the collections at Fisk and Yale he wanted to furnish environments of the mind through which scholars could have their imaginations stimulated and their prejudices challenged. Van Vechten once copied into a notebook a passage from the 1935 novel The Last Puritan, by George Santayana, that perfectly articulates his approach to his role of wealthy patron: “The use of riches isn’t to disperse riches, but to cultivate the art of living, to produce beautiful homes, beautiful manners, beautiful speech, beautiful charities. You individually can’t raise the lowest level of human life, but you can raise the highest level.”

Noblesse oblige, one might call it, an aristocratic individualism conducive with his love of material splendor and his desire to be seen as an exceptional man of foresight and influence. In the catalog he wrote for the James Weldon Johnson Collection, he left no doubt about which beneficent benefactor had laid the foundations. The catalog, an exhaustive document of 658 pages that provides information about every item and major personality appearing in Van Vechten’s gift, is a thing of mesmeric scope, reflecting the depth and breadth of his passion for African-American culture. Obscure abolitionist novels are explained alongside even more obscure eugenicist tracts; Josephine Baker and Claude McKay rub shoulders with Booker T. Washington and Charles Chesnutt. But on every page is Van Vechten. The story of his life is found scattered in fragments, conspicuously written in the third person, among the larger, more complex stories of black America postemancipation. In the entry for a biography of Paul Robeson, Van Vechten notes that one chapter includes rich descriptions of his cocktail parties at 150 West Fifty-fifth Street; on detailing a book about the history of American boxing, he draws attention to his interest in the sport and to the black fighters he has photographed; when he comes to his copy of Half-Caste, Cedric Dover’s evisceration of the pseudoscientific basis of white supremacy, he thinks it vital to note that there is a passing, unflattering reference to him on page 14. After reading a document in which Van Vechten parachutes himself into the black history of the United States at every possible moment, one might easily interpret his immense generosity in establishing the collection as lordly largess. The same often applied to his personal life. Once he had taken up photography full-time as a man of great private wealth who never need work again, certain friends felt uncomfortably beholden to his benevolence. He spent hours taking and developing photographs for them but refused to accept money or favors in return. Inevitably, this could cause frustration and resentment. After receiving some prints in the mail, Mahala Dutton—or Mahala Dutton Benedict Douglas, as she was now known—asked Van Vechten why he insisted on making people feel “so much in your debt” by refusing to accept payments for his photographs, and only ever issuing them as gifts. “I never seem able to do anything for you,” she said in a letter that balanced gratitude and exasperation.

Imperiousness was a characteristic too deeply embedded to be changed now, however. And neither should it render his objectives unworthy. His egocentrism aside, the collections at Fisk and Yale reflect Van Vechten’s glee at the vitality of American culture, a vitality created by its founding commitment to the genius of the individual. Coinciding with the outbreak of the Second World War, the act of establishing these archives of American brilliance might just have been the first and last overtly political act of his life. During the same period his revulsion for communism deepened, at a time when lots of his closest friends thought the Soviet Union Europe’s greatest hope of defeating fascism. Many of his cohorts had enthusiastically supported communism’s role in the Spanish Civil War and were attracted by its creed of class solidarity, which appeared to cut across the racial dividing lines that held the United States’ culture of segregation in place. Van Vechten had no truck with any of this. “With great pleasure,” he wrote his left-wing friend Dorothy Peterson in December 1939 a few days after the outbreak of the Winter War between the Soviet Union and Finland, “I spit on Russia and all the Russian sympathizers.” Beyond the ruthless imperialism of the Red Army there was a bigger issue: he believed that leftist ideologies promoted the idea that sameness could be a virtue, and his individualist instincts could not tolerate that notion. His disdain even made its way into the James Weldon Johnson Collection catalog when he noted that C.L.R. James’s adherence to Trotskyism fatally damaged his abilities as a writer.

When the United States entered the war with the Soviet Union as an ally, Van Vechten took the opportunity to express his fealty to his nation’s individualistic ethic by spending Monday and Tuesday nights running the Stage Door Canteen, a venue where servicemen in New York could eat, drink, dance, and socialize while being waited on by celebrities from the entertainment world. It proved such a hit that it provided the basis of the 1943 propaganda film Stage Door Canteen starring, among many other Hollywood A-listers, Katharine Hepburn. Marinoff was actually first to volunteer her services at the canteen, but when Van Vechten decided to get involved, he swiftly bundled her aside and turned the venture to his own purposes. As well as being a site of respite for servicemen away from home in the Big Apple, the canteen became another venue for Van Vechten to challenge the authority of the color line. He wrote with pride to many friends about the racial mixing he was facilitating, as black soldiers danced with white girls and got to know white fellow servicemen in a way they would never have done elsewhere. It reaffirmed his belief that political campaigns, committees, and state-run projects were no match for the transforming power of direct social contact—especially when he was in charge. He told Dorothy Peterson that the success of the canteen was “proof” of his belief that if blacks only had “nerve enough” to enter white establishments, then racism, outside the South, “could be broken down in a week.”

The naivety of that statement is breathtaking. Considering how often black friends of his had been turned away from restaurants, theaters, and nightclubs that he himself patronized, it seems bizarre that he believed the social timidity of the black community to be the biggest obstacle in defeating racism. It was the type of observation he made all the time. When the African-American academic Norman Holmes Pearson asked him to sign a petition in support of the Civil Rights Congress in 1948, Van Vechten declined the invitation, telling Pearson that he made it a rule never to add his name to petitions, before ostentatiously claiming that he had followed his own methods for opposing racial discrimination for half a century, “sometimes almost single-handed,” and with tremendous effect. He added that he had been particularly successful in challenging the behavior of the many African-Americans who attempt to “Jim Crow other Negroes.” Beyond the supercilious, self-regarding waffle, Van Vechten’s response reveals that his fixation with individual transformation blinded him to the structural nature of racism, the deep-rooted social and political issues that kept black and white America divided. When a new, more organized and politicized phase of the civil rights struggle began after the Second World War, Van Vechten could not take to its petitions, marches, demonstrations, and rallies, which, to him, emphasized collective rights over individual experiences. The unwieldy complexities of politics had no place in his scheme to “cultivate the art of living,” as George Santayana had put it in The Last Puritan. He clung to the idea that racism would be destroyed if whites and blacks were encouraged to lindy hop together on a Saturday night and that the world could be revolutionized one elegant cocktail party at a time. It was a fanciful, quixotic indulgence that could be enjoyed only by a rich white man to whom racial discrimination was an abstract problem rather than a vicious reality that blighted his daily life.

Still, there is something inspiring about Van Vechten’s inexhaustible faith in the capacity of the individual to effect change, and before his eyes at the canteen he saw young lives set on a path of self-discovery. The unusually named George George, sensitive, awkward, and barely twenty, was drawn in almost immediately when he spent an evening at the canteen, shyly watching the other soldiers spin the pretty girls around the dance floor. Van Vechten could spot the truth about boys like George a mile off. He had, after all, been just like them once, a confused outsider dreaming of escape. The currents of longing and frustration that George thought were buried deep within him surged to the surface under Van Vechten’s gaze. To George, Van Vechten was an exemplar of the life he dreamed of living. Though too self-conscious to speak at any length to him on the night, George struck up an extraordinary correspondence with Van Vechten, writing vivid and intense letters from Miami, Brazil, and all the other places he was stationed. In return Van Vechten sent him anecdotes of memorable times past and present and copies of his novels. George immediately identified with Gareth Johns, the frustrated youth at the center of The Tattooed Countess. Like Johns, George said, “I am understood by no one; liked by fewer.” He apologized for the melodrama, blaming it on his feelings of vulnerability and confusion. George came to idealize Van Vechten and described him as one of the greats of the twentieth century, an artist of beauty, poise, style, and authenticity, for whom no exaltation was too grand. The canteen was a magnet for lonely and bored young servicemen far from home—just like George—and it provided Van Vechten the opportunity to swell the numbers of the jeunes gens assortis. As he entered his old age, this seemed more important than ever; inculcating these youngsters with his values, interests, and way of living was the surest means by which his influence would live on after his death.

* * *

In the last twenty years of his life securing a legacy became the focus of Van Vechten’s work. As the forties bled into the fifties, his days were split among three principal activities: letter writing, photography, and boxing up material to be stored for posterity. He was helped in the latter two of these by Saul Mauriber, another much younger man who became the main object of Van Vechten’s sexual and romantic attentions after his relationship with Mark Lutz had settled into warm friendship in the early forties. The materials they were arranging were not just for the James Weldon Johnson Collection at Yale or the archive in memory of Gershwin at Fisk. Van Vechten was donating reams of his correspondence and personal photographs to the New York Public Library and Yale’s Collection of American Literature. Those grand institutions were only too glad to receive them. His relationships with H. L. Mencken, Gertrude Stein, the Fitzgeralds, and hundreds more are preserved in their letters to him and in their submission before his camera, providing a twisting paper trail of Van Vechten’s life and his nation’s cultural transformation.

These are the archives of a kind of cultural alchemy that took place in the United States from the start of the twentieth century, the curious tale of how the unseemly forces of modernism conquered the conventions of the past—but with a vignette depicting Van Vechten’s involvement on every page. Among the thousands of photographs he donated, by far his most common subject is himself, either shots taken by others or the hundreds of vainglorious self-portraits. He bequeathed piles of receipts, tax returns, report cards, student essays, scraps of fabric, and even a box of dried flowers that belonged to him. In the margins of letters and on their envelopes he scribbled explanatory notes about the identities of his correspondents and the people, events, and places they discuss. He was talking to the future generations he imagined poring over his belongings, narrating for them the story of the times through which he had lived. By the mid-1940s Van Vechten’s literary fame was a distant memory. His impish novels, so firmly fixed to the era in which they were written, aged poorly, and his essays on dance, music, and the theater faded almost entirely from view. In the meantime, many of his great causes had outstripped him: Stein, Hughes, Gershwin, and Robeson, for example, all were world-famous, and in 1949 Ethel Waters became only the second black woman in history to receive an Oscar nomination. Fabulously wealthy and well connected though he was, Van Vechten was frustrated by his slide from public prominence. He viewed these archives as his best chance of immortalizing himself, of leaving definitive proof of his uniqueness and the role he had played in helping the United States realize its artistic potential.

* * *

In the mountains of papers and objects he cataloged and sent away, Van Vechten exhibited his inner life in minute detail. When researchers looked through these materials in the years immediately before and after his death in 1964, they were overwhelmed by the volume of evidence that attested to those private relationships of his that hurdled the barriers of race and class. Signs of his varied sexual interests, however, were far less prominent—visible, certainly, but often obscured by codes, innuendos, and meanings that nestled between the lines. It was as if Van Vechten had excised that important part of his life from history. For myriad reasons such self-censorship would have been entirely understandable. Leading an openly homosexual life had of course never been an option for Van Vechten, but in the years during and immediately after the Second World War, the sexually playful atmosphere of the twenties, in which he had written about homosexuality with relative candor, seemed remarkably distant. J. Edgar Hoover began his grotesque campaign against homosexuality as early as 1937, ordering FBI agents to compile thousands of reports on homosexuals within the military, government, politics, and various other fields of public life. By 1947 Hoover was warning Congress that homosexuality was a key threat to national security, second only to communism, and urging President Truman to flush it out wherever it existed. His invective proved greatly persuasive. By the early fifties Senator Joseph McCarthy and numerous other prominent federal and state officials were joining in the witch-hunts, and between 1947 and 1955 twenty-one states and the District of Columbia introduced sexual psychopath laws that specifically targeted homosexuals. Life for many American gay men and lesbians was now more fearful and secretive than ever before.

In a direct sense, Van Vechten was relatively unaffected by these developments. He turned seventy in 1950, and his years of cruising in gay bars were behind him. All the same, the demonization of homosexuality enraged him, and he refused to be victimized. On his death he left instructions that certain documents, sealed in boxes, should be handed to Yale and the New York Public Library, only to be opened many years after his passing. His daybooks from the 1920s were sent to the New York Public Library, the perfect place for his shorthand chronicle of Manhattan’s coming of age. To Yale he left very different materials: boxes of homoerotic photographs and eighteen scrapbooks recording an adult life of homosexual desire. The books are a jumble of newspaper clippings, erotic and pornographic photographs, sketches, and scraps of personal correspondence, the majority of which comes from the 1940s and the 1950s, though one newspaper story included came from as early as 1917. The article in question concerned the notorious playboy Harry K. Thaw, who was jailed for kidnapping and whipping a teenage boy named Frederick Gump in a violent sexual assault. There are many clippings like that dotted throughout the scrapbooks; stories of gay bashings, of persecution, and of men, fearful that some dark secret would emerge to destroy them, who had taken their own lives. These of course were the tragic realities for all too many Americans in a pre-Stonewall society—and, to a lesser extent, continue to blight the lives of some gay people today—yet without his inclusion of them here, it would be tempting to believe that such darkness did not encroach on Van Vechten’s horizon. His treatment of homosexuality in his published writing in the 1920s was rarely anything other than exuberantly camp, some of his male characters conforming to the pansy stereotype of the day: effete, flamboyant, superficial, and unashamed of their sexual interests. His private correspondence, even with other gay men, gives little indication that he found anything troubling about his sexuality. When writing friends, often he signed off his letters with extravagant farewells that lavished imaginary gifts upon his correspondent, wonders such as exotic multicolored birds of prey, priceless jewelry, and a thousand tender kisses. When addressed to his closest gay male friends, these read like positive affirmations of a shared identity, especially when they mentioned flowers—pansies, lilies, violets, and carnations being particular favorites—as they frequently did. The tales of misery and torment in the scrapbooks show a different man, not one tortured by his sexual self but one clearly touched by the pain of those who were and angry at an intolerant world insensitive to their suffering.

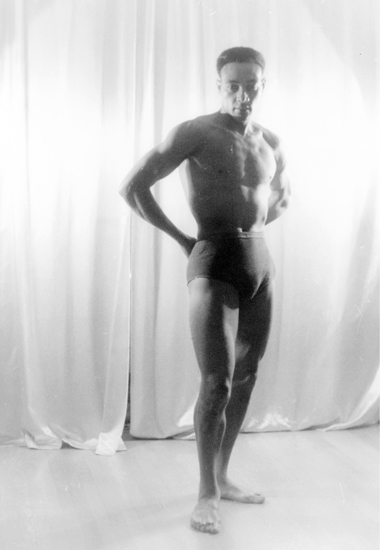

The dancer Al Bledger, c. 1938, photograph by Carl Van Vechten

Bitterness, however, is not at all the controlling mood of the books, which also document acts of astonishing bravery. Christine Jorgensen, the first publicized subject of a male to female sex change, dominates an entire page, for instance, looking elegant and defiant in a picture accompanying the headline DAD PRAISES COURAGE OF SON-TURNED-DAUGHTER. The inclusion of the press clippings, mournful or triumphant, are evidence of Van Vechten’s scrutinizing eye rooting out sexual difference wherever it appeared and conjuring it up wherever it was absent, as the historian Jonathan Weinberg has noted. This was no recent habit, of course; it had been one of his favorite pasttimes for decades, and it informed much of the scabrous conversation that so infuriated Mabel Dodge. Had the great lady seen the contents of his scrapbooks, she would have probably pitied him for his arrested development that manifested itself in this inexhaustible—and sometimes exhausting—obsession with sex. Maybe, though, she would have also admired the inventiveness of his collages that constitute the most arresting part of the books. Frequently crass and juvenile, although just as frequently hilarious, the collages appear to have been constructed mainly in the 1950s and, probably unintentionally, display a certain ironic pop art sensibility, with faint echoes of the best-known work of Richard Hamilton. It is an irresistible image: a rich, venerable silver-haired gentleman in his seventies sat in his sumptuous apartment overlooking Central Park, rearranging newspaper cuttings to make dirty jokes that he can stick in his scrapbooks and pack off to the librarians at Yale, chuckling and hissing through his crooked teeth all the while. No other scene from his rich and varied life captures so perfectly the combination of instincts that drove his creativity: the attention seeking and love of bad taste on the surface and the current of a radical cause flowing urgently beneath.

Some of the pages feature sexually explicit photographs of young men, though judging from the sheer profusion of the images and from his long-standing glee at subverting convention, one senses that Van Vechten most enjoyed assembling the pages that fuse photographs of traditionally masculine men with headlines from entirely unrelated newspaper stories, mischievously turning the images into works of celebratory homoeroticism. In the sexual revolution of Van Vechten’s collages, all sorts of famous American males, from Montgomery Clift and James Dean to President Eisenhower and Bobo Holloman, the pitcher for the St. Louis Browns, were out and proud. The obvious delight that Van Vechten took in projecting the world through a filter of homoeroticism unveils one of the paradoxes of his identity: at times he actively enjoyed the furtiveness that his attraction to men compelled him to pursue. Being unable to publicly express love and affection for other men without fear of reprisal was obviously loathsome, but still, he felt there was something to be said for the thrill of clandestine activities, forbidden pleasures, and the intense bonds forged among members of a community only permitted to exist subterraneously.

Those bonds are quietly eulogized in the scrapbooks too. Van Vechten had been an enthusiastic trader of pornography and dirty jokes for many decades. Into his seventies and eighties he was still sending Aileen Pringle, his friend of nearly forty years, letters that ended with gags about fornicating rabbis or the homosexual termite that only had eyes for woodpeckers. With the jeunes gens assortis and other friends he similarly maintained an exchange of sexual gossip, jokes, and pictures. Most of his closest friends knew that his collecting interests extended to sexual matters and were aware of his top shelf, a portion of his bookcases dedicated to erotic material as well as more serious scientific works about sex, by writers such as Havelock Ellis and René Guyon. The painter Elwyn “Wynn” Chamberlain clearly had his tongue in his cheek when he sent Van Vechten deliberately camp sketches of angels and cowboys, knowing that the old man’s ribald sense of humor would be tickled by them. Other artists gave him much more explicit material. Thomas Handforth is best known for his elegant illustrations and etchings of China, but he drew for Van Vechten a side of the Far East that was never touched upon in his award-winning children’s books: pornographic drawings of American sailors and Chinese gigolos that, unlike Chamberlain’s gifts, were designed to arouse rather than amuse.

Considerable courage was required in exchanging those drawings. During the Eisenhower years Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield crusaded against what he termed “pornography in the family mailbox” and gained extensive powers to censor any materials sent via the post that supposedly promoted homosexuality. Being caught sending or receiving homoerotic material could have ruinous consequences, including prosecution for acts of sexual deviancy. One clipping in the scrapbooks comes from One, a periodical launched in 1953 by a homophile group named the Mattachine Society, whose mission was to counteract the slew of vicious antigay propaganda, and promote the message of gay rights. The FBI infiltrated the Mattachine Society, and after One had run a story claiming that homosexuals “occupy key positions with oil companies and the FBI,” agents outed the magazine’s staffers to their employers. A retired millionaire whose wife and close friends all knew about his sexuality, Van Vechten had relatively little to lose by being similarly exposed, but still, if he was receiving One in the mail, he was knowingly opening himself up to unpleasant forces.

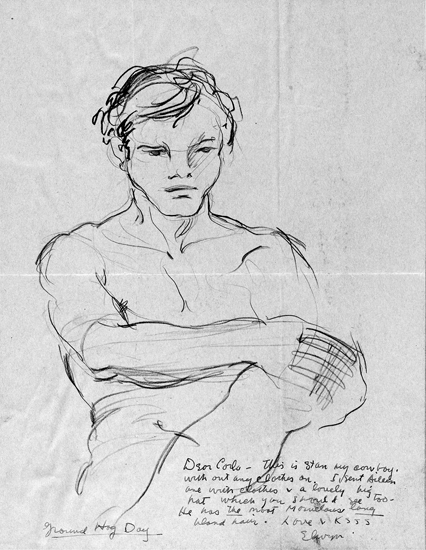

A sketch by Wynn Chamberlain at some point during the mid-1950s that Van Vechten put in his scrapbooks. Chamberlain identifies this as a preparatory sketch for Doorway, a painting that was subsequently bought by Lincoln Kirstein.

Until his suicide in 1934, Max Ewing had been one of the most prolific correspondents, and his presence is strongly felt in the scrapbooks too, especially because he had an eye for the more subtle allusions to homosexuality of the sort that Van Vechten himself was adept at spotting. “Dear Carl,” he scribbled at the top of a poster mocked up to show the Marx Brothers in drag, “For one or another of your collections of AMATORY CURIOSA!” A story about plans in Italy to censor classical scenes on postcards on grounds of taste and decency also caught his attention; he forwarded the clipping to Van Vechten with a note suggesting “we should exchange a great many very soon before the movement gets under way here.”

Ewing had picked up the photography bug around the same time as Van Vechten, and from 1932 he sent him many prints of his work, including those from his “Carnival of Venice” series, studio portraits taken in front of a Venetian backdrop. Largely thanks to Van Vechten, Ewing had befriended many of the leading lights of New York’s art establishment, and Paul Robeson, Muriel Draper, and Lincoln Kirstein all posed for his camera before the painted gondolas and canals of a two-dimensional Venice. When Ewing wrote to inform Van Vechten about a winter exhibition of the Venice series, he said he hoped all his subjects would arrive in the costumes they posed in, though as “some of them have worn no costumes at all, it will be hard on them if the night is cold.” The photos of the disrobed models made their way to Van Vechten, naturally. One featured two shirtless men: the tall and powerful Herbert Buch next to the Greenwich Village eccentric Joe Gould, half Buch’s size, slight and fragile as a baby bird. “Note the influence of ‘Freaks,’” Ewing pointed out, a reference to one of his and Van Vechten’s shared enthusiasms, the 1932 movie about the lives of conjoined twins, hermaphrodites, bearded ladies, and other sideshow performers. The diversity of human forms that Freaks exhibits enthralled Van Vechten and it remained one of his favorite movies for the rest of his life. The fact that he was apparently unmoved by any suggestion that those in the film were exploited is perhaps a reflection of contemporary attitudes toward physical disability and certainly an insight into Van Vechten’s fascination with individual difference and unordinary lives.

Gould and Buch were not pretty enough to make it onto the pages of Van Vechten’s homoerotic scrapbooks, but Ewing’s nude shot of the dancer Paul Meeres did, in addition to some of Van Vechten’s own photographs of male dancers and naked male models. His earliest nudes were taken in the summer of 1933, but it was in the early 1940s that he shot a lengthy series of pictures with his two favorite models, Hugh Laing, a white dancer, and Allen Meadows, a black youth from Harlem. Often Van Vechten shot the two together, sometimes at his studio, other times in the lush grounds of Langner Lane Farm, the Connecticut home of his friends Lawrence and Armina Langner. Shared only with a select circle of friends during his lifetime, those photos are possibly the most explicit manifestation of Van Vechten’s abiding artistic obsessions: race, sexuality, and performance. In a letter to Langston Hughes he described Meadows as “my African model,” despite the fact that Meadows was American and lived on St. Nicholas Avenue in Harlem. Yet it was an accurate description, for within the gaze of his lens that is exactly what Meadows represented: Van Vechten’s vision of the black African soul juxtaposed with the whiteness personified by Laing’s pale skin. In some shots they stand side by side, looking passively into each other’s eyes as if they are photonegatives; occasionally their hands, arms, and bodies interlock, two swirling halves of a single being. Almost always they are performing in highly stylized poses. Van Vechten might have Meadows hold an African mask in his hands or decorate him with African jewelry or a scanty piece of fabric, while Laing showed the power and elegance of his dancer’s body by stretching into a balletic position. The combination of their nudity and their performance is intriguing. Beyond the obvious pleasure he took in looking at their bodies, Van Vechten was returning to that ruling tension of American lives: the need to live honestly and unapologetically as an individual, while adopting guises to pass between a multitude of collective identities. Stood naked in the same frame, both of them revealed their inescapable selves. In performing, they embellished those selves, hinting at their potential for transformation.

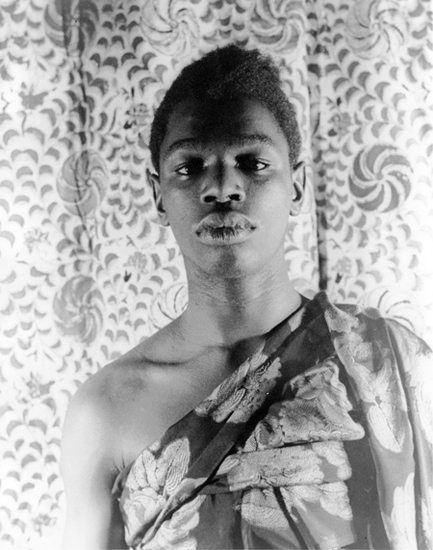

Allen Juante Meadows, c. 1940, photograph by Carl Van Vechten

Hugh Laing, c. 1940, photograph by Carl Van Vechten

While his scrapbooks suggest that his collection of pornography was considerable, there is nothing close to a porn aesthetic in the photos he took of Laing and Meadows. They are erotic, undoubtedly, but they communicate a vulnerability that robs them of the ability to merely excite or titillate. Meadows, especially, with his sad eyes and the pimples of late adolescence still visible on his forehead, has an unavoidable fragility. It was something Van Vechten was aware of, and actively accentuated. One of his favorite themes for his nudes was that of St. Sebastian, the Christian martyr who was tied to a tree by the emperor Diocletian and tortured by arrows that punctured his flesh. Since the Renaissance, Sebastian—or at least his depiction on canvas—led a double life as a gay icon, his martyrdom in the name of God serving as a metaphor for the suffering of homosexual men. “Grace in suffering,” declared Thomas Mann in reference to his novel Death in Venice, “that is the heroism symbolized by St. Sebastian.” A little more than thirty years before, when Oscar Wilde entered self-exile after his release from prison, it was no coincidence that he chose Sebastian as his pseudonym. With Meadows, Laing, and other models Van Vechten repeatedly re-created the scene of Sebastian’s torment. Each stood alone, bound and naked, pained and vulnerable; in need of protection and prone to seduction. Behind the camera and in control of the image, it was Van Vechten who had the potential to do either or both. George George believed the photographs drove to the heart of Van Vechten’s attitude toward young men in his later years, which was a mixture of caring paternalism and eroticized indulgence. George wrote a fellow Van Vechten acolyte that Carl’s fascination with Sebastian, “drilled with poison-tipped arrows launched by an intolerant society,” shows that he was sensitive to the vulnerability of youth—but he was equally enamored by Narcissus, the cocksure and conceited young man obsessed with his own beauty.

The scrapbooks and the photographs represent the one portion of Van Vechten’s life that he could not parade in public, a defiantly irreverent avocation of his innate nature and a declaration that homosexuality is a form of love and not only a form of sex—although that could be tremendously good fun too. During the Second World War he told Arthur Davison Ficke that he planned to hold on to his collections of pornography and erotica until he died. He joked that the more graphic pictures would make “life more easy in a concentration camp.” Of course that eventuality never came to pass, and instead he decided to leave them for what he hoped would be the study and enjoyment of a more enlightened generation decades after his own demise. Perhaps the choice of Yale as the recipient was influenced in part because that same institution housed a collection of the papers of Walt Whitman, that lodestone of American literature whose homosexuality also left an indelible mark on his work. Without doubt it appealed to Van Vechten’s sense of humor to bequeath this celebration of homosexuality—ribald, explicit, delicate, scatological, thoughtful, and plain silly all at once—to such an auspicious seat of learning. The setup took a quarter of a century, but when the boxes were eagerly unpacked, it was discovered that through an inscription on one of the books Van Vechten had delivered the perfect punch line from beyond the grave: “Yale May Not Think So, but It’ll Be Just Jolly.”