EIGHT

An Entirely New Kind of Negro

In May 1924 Van Vechten—out of debt and on the bestseller lists—moved with Marinoff into a new midtown address more befitting their means and celebrity. In Apartment 7D, 150 West Fifty-fifth Street, they found a large, elegant space complete with a dining room, a drawing room, and an entrance hall in which to entertain. Every square inch was adorned by some beautiful object, and visitors were overwhelmed by a bounty of artifacts the moment they stepped through the doorway: antique chairs, towering bookcases crammed with precious first editions, a gilded carriage clock, oriental rugs, oil paintings, and vases of lilies, carnations, and roses all competing for attention. Van Vechten decorated these rooms in the same way he filled his scrapbooks, every last blank space obliterated by color and curiosities. The luxury extended to separate living quarters, Van Vechten and Marinoff each having a bedroom and bathroom of their own. To their wider circle, this was an emphatic expression of the Van Vechtens’ unconventional companionate marriage. A small number of closer friends knew it was necessitated by creeping marital tensions. The sexual element of their relationship had fizzled out sometime ago, and Carl’s hard-drinking, hard-partying lifestyle was igniting the bickering that had always been one of their favored forms of communication into fearsome rows. Add to this Marinoff’s persistent insomnia, and it is clear that the separate rooms were places of refuge for both of them.

The new apartment’s mixture of material comforts and emotional volatility made it a fitting venue in which to compose Firecrackers, Van Vechten’s most abstruse novel to date. Firecrackers was another present-day tale featuring Campaspe Lorillard and Paul Moody as they continued their search for meaning and fulfillment amid the carnival madness of Jazz Age New York. The action begins with Moody reading a novel about the Tattooed Countess’s relationship with Gareth Johns in Paris, though his attention is not held for long: “It was Paul felt, rather than thought, too much like life to be altogether agreeable.” That moment of self-referential humor sets the tone for the rest of the novel, which reads like one long inside joke about modish Manhattan circa 1924. Psychoanalysis, self-improvement philosophies, the cult of youth, pansexual desire, excessive drinking, and an obsession with athleticism and physical perfection all contribute to make Firecrackers as “of the moment” as The Great Gatsby, a book published that same year. Van Vechten had particular fun sending up the present craze among Manhattan socialites and intellectuals for the teachings of George Gurdjieff, the Armenian spiritualist who claimed that his repertoire of ancient dances held the key to complete spiritual enlightenment. Van Vechten’s skepticism inured him to Gurdjieff’s charms, and his methods are ridiculed in Firecrackers as specious opportunism.

At the end of the novel’s madcap, frolicking narrative one is unsure whether to laugh at the gaiety of the pageant or sneer at its shallowness. The author himself no longer knew. Both in his daybooks and in letters to friends Van Vechten admitted that he could not quite articulate what this latest opera buffa was really about. His low-boredom threshold was partly to blame; there were only so many tales of fashionable excess that could be written before the novelty wore off. Mabel Dodge pointed out something more pertinent: that Van Vechten’s life was wedged in a familiar groove, endlessly repeating the luxuriant lunacy of his fiction. After visiting New York for a few days during the summer, she wrote him a series of stern rebukes for clinging to a lifestyle that appeared to her to be faintly pathetic, like a prolonged adolescence. “You’re too evolved really to be amused by the facts of crude sex in any of its inter relations—rape or whoredom—or bed athletics of whatever kind,” she said, referring to the smutty conversations he’d had with Avery Hopwood in her presence. “You make me sorry for you when I hear you still trying to raise the wind over any of these old and overworked manifestations.” Following Van Vechten’s protestations against these derisive remarks, Mabel put her case as plainly as possible in a subsequent letter: “who sleeps with who isn’t funny anymore.” Clearly she felt he needed some new external stimulus to lift his mind to higher matters. When it arrived, it came from a source that surprised them both.

* * *

On June 19 Van Vechten finished redrafting the eighth chapter of Firecrackers and settled down to read a book passed to him by George Oppenheimer, an editor and publicist at Alfred A. Knopf. What he found between its pages dazzled him: “a great negro novel.” Fire in the Flint, was an impassioned protest against segregation, written by an African-American writer named Walter White. This was White’s first novel, inspired by his experiences of investigating racial violence on behalf of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), an organization for which he was then the assistant secretary and was to go on to successfully lead between 1931 and 1955. Consequently, his novels had a fiercely polemical edge, the sort of thing Van Vechten usually dismissed as propaganda rather than literature. Not so Fire in the Flint; Van Vechten was enthralled by the ferocity of its rage against a cruel white society and given a new insight into a type of American life far removed from his own.

“I had no idea that you would be so interested in a novel such as mine,” wrote White on learning of Van Vechten’s appreciation, clearly astonished that the Wildean chronicler of Manhattan sophisticates should be concerning himself with the serious business of southern race relations. Intrigued by his new fan and acutely aware of the commercial implications of having a well-connected trendsetter behind his novel, White was only too happy to accept the invitation to pay him a visit. The two men met at the Van Vechtens’ apartment on August 26 and hit it off immediately. White told stories about how his light complexion allowed him to cheat segregation; Van Vechten enthused about Fire in the Flint and advised on how it might be adapted into a stage play. Even after several hours, when Avery Hopwood arrived with his boyfriend John Floyd, both steaming drunk and wanting to party, Van Vechten could not be tempted away from his latest discovery and shooed them off.

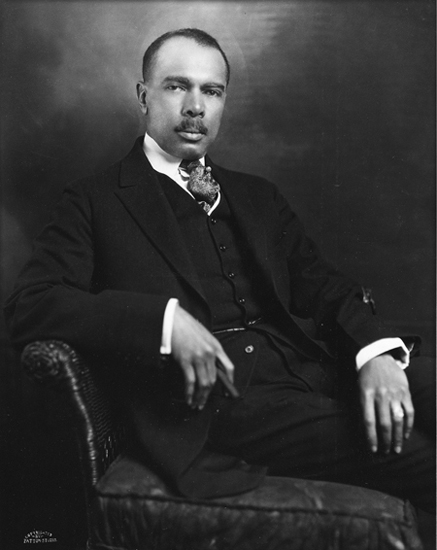

Walter White, c. March 1942

That August afternoon was a revelation for Van Vechten. For years he had sought out African-American culture in places most white people would never have dreamed of venturing. But until he read Fire in the Flint, his idea of blackness was a caricature centered largely on physical performance. Mrs. Sublett’s prayer rituals, the “Negro Evening” at Mabel’s salon, the display of the Holy Jumpers in the Bahamas, Bert Williams’s genius on the stage, even a growing interest in prizefighting: all suggested to Van Vechten that black people could captivate audiences with their voices, faces, hands, and feet, but not with the written word. In his 1920 essay “The Negro Theatre,” Van Vechten said that while “most Negroes have a talent for acting,” he had yet to encounter an accomplished black playwright who could capture the experience of being a Negro in the way that the best black actors could. J. Leubrie Hill’s 1913 show My Friend from Kentucky, which Van Vechten had reviewed in the New York Press, was still his benchmark of black creativity, sensual and unrestrained. “How the darkies danced, sang, and cavorted,” he exulted in “The Negro Theatre.” “Real nigger stuff, this, done with spontaneity and joy in the doing. A ballet in ebony and ivory and rose. Nine out of ten of those delightful niggers, those inexhaustible Ethiopians, those husky lanky blacks, those bronze bucks and yellow girls would have liked to have danced and sung like that every night of their lives.”

This was Van Vechten’s essential idea of the black artist. Walter White therefore was an unknown quantity: a high-minded black man who used his brain rather than his body for creative expression yet managed to maintain, as Van Vechten saw it, an authentic black identity in his writing. He wrote an excited letter to Mabel trumpeting his new discovery and urged her to tell everyone she knew about him. “He speaks French and talks about Debussy and Marcel Proust,” he told Edna Kenton. “An entirely new kind of Negro to me.” He could have been describing a precocious child rather than a thirty-one-year-old graduate of Atlanta University and the assistant secretary of the NAACP. Making an intellectual connection with a black novelist genuinely excited Van Vechten, but in the presence of white friends like Kenton he felt compelled to show off, talking of White as his latest novelty. He told Kenton that White was apparently not a one-off: there was an entire community of other literary Negroes. He told her that he hoped to learn more about these “cultured circles.”

And indeed he did. Van Vechten could not have picked a better guide to lead him into black Manhattan society had he advertised for one in The New York Times. As Van Vechten described him, Walter White “was a hustler.” He shared Van Vechten’s tendency to value people in terms of their usefulness to him, and though their friendship in these early days was warm, each eyed the other up as a potential asset, White recognizing the benefits Van Vechten’s influence could bring to his career and to the African-American cause; Van Vechten seeing White as a fast track to the “cultured circles” in black society. Van Vechten admitted that their relationship was opportunistic in 1960, around five years after White’s death. “I was never completely sold on Walter,” he said. Explaining how they had grown apart over the years, he said that as time passed, “I was no particular use to him and he was less use to me.” From that casual remark one would never guess that Van Vechten was talking about an old friend who had actually named his son Carl in his honor. The best he could muster in White’s memory was that “he served his purpose.”

White ushered Van Vechten into the center of Harlem, the uptown Manhattan neighborhood that absorbed the majority of the vast flow of black people into New York City in the early twentieth century, some as immigrants from the African and Caribbean colonies of declining European empires, others as migrants from the racially divided South. Harlem was the crucible for a self-confident black identity attuned to modern America, the New Negro, as it became known. Celebrated examples of this postwar urban blackness were as diverse as they were numerous. Madam C. J. Walker, whose parents had been born into slavery, became the United States’ first female self-made millionaire producing and selling beauty products specifically for black women. Her daughter, A’Lelia, dressed in silk robes, turbans, diamonds, and furs, was the queen of the Harlem social scene, hosting legendary parties at her properties on Edgecombe Avenue and 136th Street. W.E.B. DuBois, black America’s leading intellectual, edited The Crisis, the official publication of the NAACP, which dedicated itself to issuing “uplift” propaganda designed to galvanize “the talented tenth” of African-American writers and thinkers. Marcus Garvey led thousands in parades through Harlem’s streets under the flag of the Universal Negro Improvement Association. There was even a black Lindbergh, Hubert Julian, who attempted a transatlantic flight from New York to Liberia. These people were just a few members of the varied groups of black artists, activists, and entrepreneurs responsible for what is now called the Harlem Renaissance, one of the most vibrant and important American cultural moments of the twentieth century, which helped push black culture into the national mainstream as never before. In the words of one of its most celebrated citizens, the writer and diplomat James Weldon Johnson, Harlem “was a miracle straight out of the skies.”

Van Vechten’s initial reaction to mixing in black company that encompassed showgirls, vaudevillians, polemicists, and poets was one of enchanted disbelief; it was the type of thing that only New York could offer, one that not even Campaspe Lorillard had experienced. In November, as keen as ever to show off to his idol, he told Gertrude Stein that his latest diversions were “Negro poets and Jazz pianists.” His lightness of tone made it sound as though he expected his Negrophilia to go as suddenly as it came. But unlike birds’ eggs, the music of Richard Strauss, Italian theater, and his many other fancies, this was to prove no passing whim.

Over the ensuing months Van Vechten became, in his words, “violently interested in Negroes. I would say violently, because it was almost an addiction.” With trademark speed he worked his way through the great texts of an American literary tradition hitherto unknown to him. He mined DuBois’s seminal The Souls of Black Folk and the novels of Charles Chesnutt. He also discovered a bold and ambitious younger generation of writers who constituted the creative heart of the Harlem Renaissance, expressing the reality of what life was like for young, urban blacks in the new century. He especially admired Jean Toomer’s radical modernist novel Cane; the poems of Countee Cullen, some of which H. L. Mencken published in The American Mercury; and the urgent short stories of Rudolph Fisher sent to him by Walter White. The work that affected him most was The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, a pained but beautiful novel by James Weldon Johnson. The novel centered on the experiences of a black man passing as white, a subject that fascinated Van Vechten. Johnson was the national secretary of the NAACP, and after being introduced by Walter White, he and Van Vechten became firm friends. For the length of their friendship Van Vechten was astonished by the range of Johnson’s talents: he was a gifted musician, an accomplished writer, a skilled diplomat, a shrewd politician, and one of the few black lawyers to be admitted to the Florida bar. It seemed there was nothing he could not do. In awe of his talents, Van Vechten held Johnson up as one of the great living Americans, black or white, as flawless in his eyes as Gertrude Stein.

James Weldon Johnson, c. 1920

Schooling himself in African-American cultural history by day, by night Van Vechten developed an obsession with the physical experience of Harlem, “the great black walled city,” as he described it. Of course Van Vechten’s encounters with the Tenderloin and Chicago’s Black Belt meant he was no stranger to African-American neighborhoods after dark. Harlem itself was not entirely unknown to him. In recent years he had occasionally visited theaters in the area and browsed the numerous bookstores that peppered 125th Street. But under Walter White’s guidance Van Vechten became acquainted with black people from all backgrounds, from straitlaced social workers to brash artists with smart mouths, sharp minds, and a thirst for hard liquor to rival his own. Very quickly Harlem ceased to be simply another of New York’s many exotic diversions that kept Van Vechten amused; it became his all-consuming passion, the absolute center of his social universe.

In 1924, if white people had any familiarity with Harlem’s nightlife, it generally came in the racially segregated venues whose names are still known around the world today. The Cotton Club, on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue, was a temple of primitivism: African drums, African sculpture, and a sprinkling of wild vegetation allowed white patrons to feel as though they had stumbled upon tribal rites in a jungle clearing. The only black people allowed in were the dancers and jazz musicians hired to entertain the white customers and a select band of celebrities to provide a veneer of exotic glamour. Similarly, the Plantation Club on 126th Street between Lenox and Fifth Avenue, catered to a farcical antebellum fairy tale. Log cabins and picket fences dotted the club’s interior while African-American women in the role of dutiful, chuckling mammies tossed waffles and flapjacks on demand for hungry white customers. When the club was smashed to pieces by a gang in the employ of a rival speakeasy owner in January 1930, The Afro American newspaper reported that “Harlem is laughing—long and loud. It refuses to be segregated in its own home.” These clubs were in Harlem but clearly not of it.

By and large Van Vechten avoided those places, dedicating himself to what he considered the real Harlem, where black people could be encountered as drinking pals and not merely as entertainers. Small’s Paradise, at 2294 Seventh Avenue, was one of his preferred haunts and arguably the pivotal social venue of the Harlem Renaissance: an upmarket—“dicty”—“black and tan” club, deliberately catering to whites but welcoming blacks. Small’s main attraction was its cadre of lithe waiters, who Charlestoned their way from table to table, spinning on the balls of their feet, knees darting inward, trays of drinks and plates of Chinese food held high above their heads. The tables on which they waited enveloped a tiny dance floor that was always packed. Patrons of all colors pressed up close against one another, the air between them thick with perspiration, as they ground their bodies to the gutbucket, the long, meandering jam sessions performed by the club’s resident jazz band.

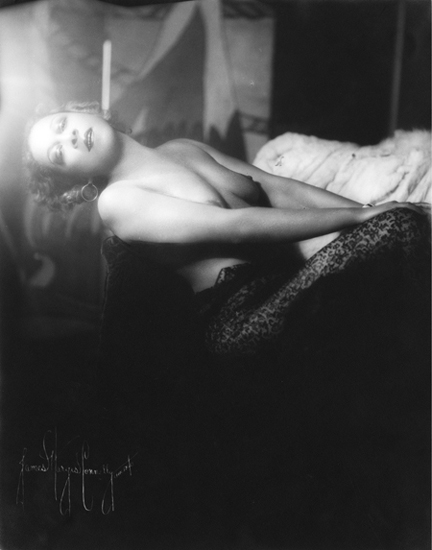

Small’s was the hip joint, the place to be seen, a little like the uptown Algonquin. Van Vechten could not resist that, but what excited him most were the low-down venues that the Harlemite Claude McKay described as “bright, crowded with drinking men jammed tight around the bars, treating one another and telling the incidents of the day. Longshoremen in overalls with hooks, Pullman porters holding their bags, waiters, elevator boys. Liquor-rich laughter, banana-ripe laughter.” The Nest fitted the bill perfectly: a scruffy, smoke-filled, after-hours den in the basement of a brownstone house on 134th Street. Its clientele was almost exclusively black, including many performers from more salubrious spots who came there to unwind after long sets. Nora Holt was among them: an unconventional and gifted cabaret singer who captivated Van Vechten from their first meeting. Describing Holt to Gertrude Stein, he expressed her charms as exotic, outrageously funny, “adorable, rich, chic,” and plenty else besides. Born in Kansas City in 1885, Holt was christened Lena Douglas but changed her name after each of her five brief and turbulent marriages, the first of which she entered at the age of just fifteen. In 1918 she became the first black woman to receive a master’s degree from the Chicago Musical College, and she worked for many years as a teacher, composer, and music critic, during which time she founded the National Association of Negro Musicians. But like Van Vechten, she also claimed to have performed at the Everleigh Club brothel in Chicago, and she gained terrific notoriety for her extramarital affairs and her penchant for stripping off and dancing naked at parties.

Perhaps more than any other Harlemite he encountered, Holt expressed within one body what Van Vechten regarded as the ideal elements of black identity: the urbane and thoughtful “entirely new type of Negro” that Walter White had astounded him with as well as the physically expressive and sexually charismatic type that he had romanticized since childhood. Harlem had the curious effect of both dismantling and reinforcing his stereotypes of black people. Despite introducing him to a group of educated African-Americans whom he had previously never given any thought to, Harlem was also Van Vechten’s place of escapism, a land of freedom and abandon where fantasies came to life. The Committee of Fourteen and New York City’s other powerful moral guardians who had asserted themselves during the Progressive Era were not nearly as interested in monitoring vice and criminality in Harlem as they were in predominantly white areas of New York, just as they had steered a wide berth of the Tenderloin in years gone by.

Harlem’s permissiveness manifested itself in numerous ways. Nightclubs in the neighborhood had a rampant drug culture, even at high-profile venues like Small’s Paradise, where Avery Hopwood, among others, went for an opium fix; Van Vechten, never a big drug user, likely contented himself with the odd joint and line of cocaine. To the annoyance and revulsion of the community’s churches and social conservatives, Harlem also offered greater sexual freedoms than most other New York locales, especially to white homosexuals. To echo Henry Louis Gates, Jr.’s famous declaration, the Harlem Renaissance “was surely as gay as it was black.” The male writers Van Vechten socialized with in Harlem’s nightclubs included Countee Cullen, Eric Walrond, Alain Locke, Wallace Thurman, and Richard Bruce Nugent, all pivotal figures of the renaissance, all gay, and, with the exception of Cullen, more open about their sexuality than the majority of homosexual men of the era.

Nora Holt, c. 1930

Richard Bruce Nugent was so frank about his homosexuality he made Van Vechten seem like a sheltered bumpkin from The Tattooed Countess. In his extraordinary short story “Smoke, Lilies and Jade,” Nugent appears as Alex, a young man who picks up a stranger at four in the morning and brings him back to his apartment. As “they undressed by the blue dawn,” Nugent wrote, “Alex knew he had never seen a more perfect being … his body was all symmetry and music … and Alex called him Beauty.” It is worth noting that Nugent once wrote Van Vechten to express his admiration of Peter Whiffle—unsurprising considering that Whiffle’s declaration to do “what one is forced by nature to do” mirrored Nugent’s own philosophy for living. “Harlem was very much like the Village,” Nugent recalled decades after the Harlem Renaissance had passed. “People did what they wanted to do with whom they wanted to do it. You didn’t get on the rooftops and shout, ‘I fucked my wife last night.’ So why would you get on the roof and say, ‘I loved prick’? You didn’t. You just did what you wanted to do. Nobody was in the closet. There was no closet.”

Nugent was surely overstating his case in that instance. But there was unquestionably an atmosphere of liberation in Harlem at night that outstripped most of the city’s other neighborhoods. Van Vechten was a regular and enthusiastic guest at A’Leila Walker’s extravagant parties, infamous for their same-sex and interracial exhibitionism, and he befriended Walker’s circle of rent boys and pimps. In one of his first turns as tour guide of Harlem for white outsiders, Van Vechten took the English writer Somerset Maugham to a Harlem institution at the other end of the social spectrum, a buffet flat. There were dozens of these venues in Harlem, modest apartments in which various rooms were rented out for gambling, sex shows, and orgies. In small, dimly lit rooms heaving with bodies, soft cushions, and throws scattered on the floor, this was where the fantasies of white tourists like Van Vechten came vividly to life. Any combination of people—black, white, male, female—enjoyed anonymous sexual encounters as the sound of hot jazz tunes rippled out from a phonograph or an upright piano. “All around the den”—Claude McKay described the atmosphere in one Harlem establishment—“luxuriating under little colored lights, the dark dandies were loving up their pansies. Feet tickling feet under tables, tantalizing liquor-rich giggling, hands busy above.” In a Harlem buffet flat, there was no curb on the sexual possibilities. The former Vanity Fair editor Helen Lawrenson described in her memoirs one notorious place that reputedly listed Cole Porter among its return clientele and featured a “young black entertainer named Joey, who played piano and sang but whose specialité was to remove his clothes and extinguish a lighted candle by sitting on it until it disappeared.”

The ethical dimensions of sex tourism never entered Van Vechten’s mind. He was too enamored by the atmosphere of transgression and fantasy to be bothered about the fact that buffet flats and rent parties existed mainly as imaginative—or desperate—ways for people to pay their bills. However, it was not the use and abuse of his wealth and status that Van Vechten found arousing. Harlem was sexually attractive to him mainly because it was a point of fusion among his homosexuality, his fascination with blackness, and his natural voyeurism. Neither was Harlem, in any of its guises, the exclusive focus of Van Vechten’s sexual interests. He was part of the select crowd at Bob Chanler’s House of Fantasy, where heterosexual porn movies were projected, and he badgered Arthur Davison Ficke to obtain Japanese pornographic art on his behalf. One night at his friend Ralph Barton’s midtown apartment in September 1925 Van Vechten watched Barton and his wife “give a remarkable performance. Ralph goes down on Carlotta. She masturbates and expires in ecstasy. They do 69, etc.” “Performance” here is the operative word. In moments of sexual encounter more often than not Van Vechten reverted to type: the sharp-sighted critic reveling in the spectacle.

* * *

At home sexual exhibitionism was substituted for something less scandalous yet still with the power to shock, as Van Vechten brought Harlem down into the fashionable circles south of Central Park. From the first weeks of 1925 he and Marinoff routinely invited black people into their home—not as servants or novelty entertainers but as guests, a practice almost unheard of in white New York.

The entire block knew when it was the night of a Van Vechten party. Taxicabs and chauffeur-driven limousines lined up along West Fifty-fifth Street, decanting illustrious passengers into the lobby of 150, the doorman escorting them to the elevator. They were millionaire bankers dressed in jet-black tuxedos and stiff white collars and Hollywood movie stars in mink coats and strings of iridescent pearls, Harlem jazz musicians, and chorus girls rushing from Broadway shows, the smell of greasepaint still faintly detectable beneath their perfume. Van Vechten welcomed each guest at the apartment door like an old and cherished friend, no matter how recently they had become acquainted. Within seconds they had a drink in their hand, a cocktail made from Jack Harper’s premium bootleg liquor mixed by Van Vechten himself. Entertainment was usually provided by some combination of the remarkable talents on the guest list: a recital by Marguerite d’Alvarez in her clipped, powerful contralto; a reading by James Weldon Johnson, his voice deep and sonorous. George Gershwin was virtually the resident pianist. “He was extraordinary. It was impossible to get him off of [sic] the piano stool after he settled there,” Van Vechten recalled. “He used to play all night without ever repeating anything.”

Inside 7D Van Vechten replicated all he had learned from Mabel’s Evenings with one key twist. At his salon the byzantine rules of racial division that existed beyond his front door were suspended. Here white society magnates and struggling black artists drank and laughed and danced the Charleston together, as equals. He knew the damage that could be done to racial prejudice through the simple act of socializing because he had experienced it firsthand. One night he came home from Harlem and told Fania “in great glee” that he had just met a black person he had not taken to. “I’d found one I hated,” he recollected to an interviewer. “And I felt that was my complete emancipation, because now I could select my friends and not have to know them all.” He continued, “Up to that time, I had considered them all as one.” There is something perverse about that statement; usually one would expect to have one’s racial prejudices challenged by making friends with those from other ethnic communities. However, this was not Van Vechten indulging in a Wildean inversion of conventional logic; he meant what he said. Since his college days he had idealized black people and inadvertently reduced them to generic character types rather than real people. This moment of epiphany reinforced his conviction that to humanize one race in the eyes of the other, there was no better method, he felt, than shutting them in a room, plying them with drink, and letting nature take its course.

Tales about what went on at the Van Vechten’s interracial parties became part of Manhattan lore in the 1920s and 1930s. Most repeated was the story of the night that Bessie Smith came to perform in December 1928. The account that Smith herself was fond of telling has it that upon her arrival Van Vechten flounced up to her and offered “a lovely, lovely dry Martini.” Smith, who was already drunk, apparently screwed her face up and said she had never had a martini, dry, wet, or any other kind, and wanted nothing but straight-up whiskey. Recoiling from Van Vechten’s fussing, she downed the first whiskey shot, then a second, and a third. Fortified by liquor, she launched into a short but mesmerizing set of blues standards in the style that Van Vechten described as “full of shouting and moaning and praying and suffering, a wild, rough, Ethiopian voice, harsh and volcanic, but seductive and sensuous too.” When it came time for Smith to leave, Marinoff, full of her usual theatricality, flung her arms around the singer and attempted to give her a kiss goodbye. Smith apparently threw Marinoff to the floor, yelling, “Get the fuck away from me!… I ain’t never heard such shit,” and stormed out, leaving Van Vechten to scoop his wife up from the hallway rug while horrified guests stared on.

Across the years the story has been told and retold, used either to convey Smith’s uncompromising character or to ridicule Van Vechten’s obsession with African-American culture, mocking him as a wealthy white aesthete trying to insinuate himself with the black working class. It is worth noting that the anecdote is based entirely on Smith’s recollection, which, considering how intoxicated she was, may not have been 100 percent clear. Van Vechten does not appear to have written any account of the incident to friends, and his daybook records only that Smith arrived drunk and sang three numbers. Nevertheless, at a time when intimate social interaction between blacks and whites was conspicuously unusual the anecdote soon did the rounds because it sounded plausible: to those who spread the story, discord and confrontation seemed the inevitable outcome when white high society mixed with black blues singers late at night, everybody soused.

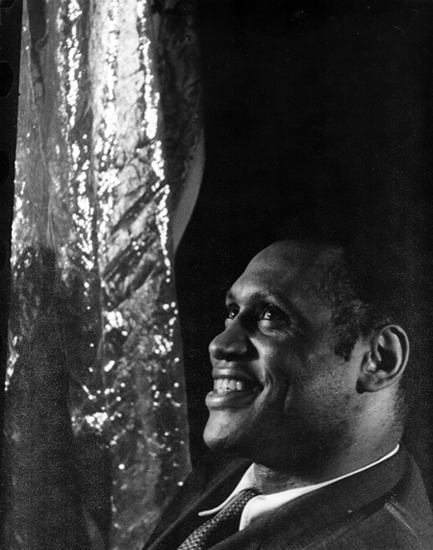

The night of Smith’s appearance might have produced the most gossip, but Van Vechten’s most important party occurred on January 17, 1925, when he welcomed Paul Robeson and his wife, Eslanda—Essie to friends—into his home for the first time. A few days earlier Van Vechten had heard Paul singing spirituals at Walter White’s home and was keen to have him repeat the performance at 150. In front of some of the most influential figures in New York, including Alfred and Blanche Knopf and the investment banker and chairman of the board of the Metropolitan Opera House, Otto Kahn, Robeson performed arrangements by his musical partner Lawrence Brown. Though he had taken up acting only within the last two years, Robeson was an emerging celebrity, having earned excellent reviews in 1924 for his performances in the Eugene O’Neill plays The Emperor Jones and All God’s Chillun Got Wings. Even so, he and Essie realized that performing at a Van Vechten party in the presence of so many opinion formers and wealthy patrons was an opportunity to showcase his singing talent and accelerate his career. Robeson’s short set caused a sensation among Van Vechten’s guests. Van Vechten wrote his friend Scott Cunningham to tell him how marvelous the party had been, thanks to Gershwin’s piano playing and Adele Astaire’s dancing. But the highlight, he said, had been the “really thrilling experience” of hearing Paul Robeson sing spirituals in a way only he could.

Van Vechten believed spirituals to be the purest expression of African-American experience and that “the unpretentious sincerity that inspires them makes them the peer of any folk music the world has yet known.” He was sure that Robeson—handsome, charismatic, and gifted with an incomparably beautiful voice—was the man to convince white audiences that spirituals were an American cultural treasure. In collaboration with Walter White and Essie Robeson, Van Vechten set about organizing and publicizing Robeson’s first solo concert at the Greenwich Village Theatre on April 19, even managing to persuade his friend Heywood Broun, an influential critic and journalist, to dedicate his column on the day before the concert to Robeson. The event was a resounding success: the house sold out, and hundreds had to be turned away at the door; Robeson performed sixteen encores to rapturous ovations from the almost exclusively white audience. Reviews in the newspapers were equally effusive, heralding Robeson as “the new American Caruso.” To Gertrude Stein, Van Vechten likened Robeson to Fyodor Chaliapin, which, considering his hero-worship of the Russian singer, was high praise indeed.

* * *

In public Van Vechten embodied the carefree spirit of excess and experimentation that defined Manhattan’s Jazz Age adventure. In private the frenetic lifestyle was taking its toll. Every wild night brought hangovers, exhaustion, and physical discomfort, a grim confluence that he often attempted to break with yet more cocktails. The fractures previously apparent in his marriage were forced open. More than once, drunk and angry, he was “rough” with Marinoff, in the euphemism of his own diary, forcing her to stay the night with friends while he calmed down and sobered up. On occasion she removed herself from New York entirely with trips to Atlantic City and farther afield. Their periods of separation frequently caused them more upset and annoyance than the fraught time they spent together. When Marinoff set off for a trip to London in April 1925, Van Vechten, pained at the prospect of their temporary separation, accompanied her to the docks. During her trip each wrote to the other of how unhappy they felt at being apart. Van Vechten’s letters were particularly lachrymose. Life was pathetic and worthless without her, he wailed, and he grumbled that her declarations of love were less frequent and heartfelt than his. Yet he made no effort to curb the behavior that was causing Marinoff such upset. The evening after she left New York he joined Angus and friends for a rip-roaring night out at a gay-friendly speakeasy named Philadelphia Jimmie’s and other Harlem nightspots, returning as the sun came up at dawn. It was a sign of his essential immaturity. Composing grand romantic gestures for a loved one far out of reach had become something of a specialty of his; changing his selfish behavior to demonstrate the undying love he professed was something he had not mastered. Anna Snyder had spotted the tendency twenty years earlier, when she accused him of caring more for “symbols than reality” in the love letters they shared. Two decades on, little had changed. Responsibility still bored him; it was a loathsome distraction from the festival of self-indulgence that he wanted life to be.

Paul Robeson, c. 1933, photograph by Carl Van Vechten

Marinoff would have been approximately two-thirds of her way across the Atlantic that spring when Van Vechten accompanied the Harlem writer Eric Walrond and the white actress Rita Romilly to the inaugural awards dinner of the monthly black publication Opportunity, the journal of the civil rights organization the National Urban League. Opportunity’s subtitle, “A Journal of Negro Life,” gives a good indication of its purpose: to exhibit the full continuum of African-American experience and opinion. Its editor, the sociologist Charles S. Johnson, belonged to a different era from that of W.E.B. DuBois, who used his editorship of the NAACP’s magazine The Crisis as propaganda for the political cause of racial uplift, committed to always presenting black people in their proverbial Sunday best. Johnson wanted Opportunity to be a debating chamber rather than a propaganda sheet and opened its pages to a lively mix of up-to-the-minute social research and the brightest talents of an emerging generation of black writers who explored and exposed black life in the round, street gambling, buffet flats, and nightclubs included.

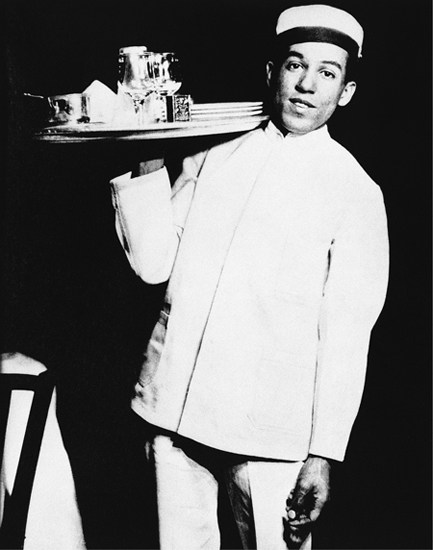

The most exciting and important of those talents was Langston Hughes, an unknown twenty-three-year-old college student from Washington, D.C, who was creating a lot of excitement with his sonorous blues poetry. At the awards that night Hughes won first prize and read aloud some of his work to the assembled guests in their finery.

Droning a drowsy syncopated tune

Rockin back and forth to a mellow croon

As Hughes recited those opening lines to “The Weary Blues,” his poem about a Harlemite “who sang the blues all night and then went to bed and slept like a rock,” Van Vechten sat listening, bewitched. Hughes’s poetry was intelligent, stylish, and modern but also fun-loving and steeped in his racial identity, what he himself described as a “heritage of rhythm and warmth.” The blues was a natural source for his work because it contained not only the historical experience of black America but also everyday life as lived by “the low-down folks” who “hold their own individuality in the face of American standardizations.” If DuBois and his followers always wanted to present African-Americans to the outside world scrubbed and groomed, Langston Hughes was happy to have the white folks take them as they found them, as “people who have their hip of gin on Saturday nights” and are happy “to watch the lazy world go by.” It was an entirely new type of poetry to Van Vechten: colloquial and sensual in a way that captured the raw emotion of the blues. To his ears it was both unmistakably black and distinctively American.

At some point that evening Van Vechten asked Hughes if he might be permitted to show the Knopfs some of his poems. Hughes said yes without hesitation. For a young, penniless black poet unknown outside literary Harlem, the prospect of having his work placed with the most fashionable publishing house in New York was the stuff of dreams. At five o’clock the following afternoon Hughes arrived at Van Vechten’s front door with his manuscript. Van Vechten had been out drinking until 7:30 a.m., had barely slept and was not in an ideal state to study poetry. Still, he was eager to read Hughes’s work and promised to do so right away. When Hughes dropped in again the following day, on his way back home to Washington, Van Vechten gave him a list of instructions about which poems should be excised and which edited in order to turn his mass of unfettered creativity into a commercially viable edition of poetry. Van Vechten had a title for this revised manuscript too: The Weary Blues, the title of Hughes’s prizewinning poem. With everything in place he handed the manuscript over to the Knopfs, urging Alfred and Blanche not to let some other publishing house snap the boy up. Two weeks later Hughes received a letter from Van Vechten to say that all was arranged: Alfred A. Knopf was to publish the book. “I shall write the introduction and the cover design will be by [Miguel] Covarrubias,” he announced, referring to the Mexican artist. Hughes was astonished. “You’re my good angel,” he gushed. “I’ll have to walk sideways to keep from flying!”

Hughes’s obvious delight was qualified by a nagging doubt about how his association with Van Vechten might look to other black people. He worried that being plucked from obscurity by an attention-seeking dandy from downtown would only give further fuel to those older, more established literary figures in Harlem who thought his poems pandered to white stereotypes of black life, focusing too much on jazz, whiskey, and sex. His fears were prescient. Over the years—and especially after the publication of Van Vechten’s hugely controversial novel Nigger Heaven in 1926—the impression that Van Vechten somehow exploited or led Hughes astray has persisted. In reality, Van Vechten’s input into The Weary Blues was little more than it had been with Firbank’s Prancing Nigger a year earlier. He haughtily assumed control of the project by shaping it into a publishable book and made sure that everyone knew of his connection to Hughes by writing the book’s introduction, but the themes, subjects, and style of Hughes’s work were never significantly affected by Van Vechten. Despite their differences in age and social status, they were friends, not patron and client or even mentor and protégé. And contrary to the rumors that have floated down the decades, neither were they lovers. Whether or not Hughes was sexually attracted to men is difficult to discern. The same cannot be said of Van Vechten, whose flirtatious correspondence with the men he had affairs with was full of homosexual coding and innuendo. His letters to Hughes feature none of that and disclose nothing but warm, jovial friendship and honest exchanges of opinions.

“The influence, if one exists,” Van Vechten said of their relationship, “flows from the other side.” In his very first letter to Hughes, written while arranging a publishing deal for The Weary Blues with Knopf, it was Van Vechten who was seeking instruction, asking for information about raunchy southern ballads and recommendations for books about Haiti. Soon after, he also elicited Hughes’s help in writing an article about the blues for Vanity Fair and quoted him at length in doing so. Van Vechten was in awe of Hughes’s talent. It had taken him until his mid-thirties to find his writing voice; Hughes had discovered his while still in college, and crafting his lyrical jewels seemed to come as naturally to him as breathing. Even if Van Vechten had wanted to, Hughes was far too talented and self-confident to allow Van Vechten to manipulate or control him. Around the same time he met Van Vechten at the Opportunity awards, Hughes encountered the successful poet Vachel Lindsay, who gave him a marvelous piece of advice: “Do not let any lionizers stampede you.” Hughes never did. When he declined Van Vechten’s words of advice or ignored lengthy criticisms of some latest work, Van Vechten’s bottom lip might jut out a little, but their friendship was never seriously affected. Hughes’s innate emotional intelligence enabled him to intuitively realize what many others failed to: that despite his proprietorial tendencies, Van Vechten could reconcile himself with not being in control of a particular situation, so long as he was made to feel brilliant, unique, and admired. As Richard Bruce Nugent remarked, all Van Vechten really wanted was to have his head patted and to be told he was “a nice boy.”

Langston Hughes working as a busboy at the Wardman Park Hotel, Washington, D.C.

The same was essentially true of Van Vechten’s relationship with Paul Robeson. As Robeson’s career entered the stratosphere in the months after those first concerts, Van Vechten was a constant and key adviser and played a pivotal part in convincing Otto Kahn to lend the Robesons five thousand dollars to clear off a mounting pile of debt. Early in their acquaintance, perhaps wary that he did not appear too proprietorial over Paul’s professional activities, he joked with Essie that he was “beginning to sound like a grandpa, always offering advice. Remember that it is the advice of a friend. Reject it when it does not meet your approval. The friendship will remain.” And so it did—at least until Robeson infuriated Van Vechten by not paying him sufficient attention during the late 1930s. Van Vechten could stomach having his advice rejected, but his ego would not tolerate being ignored altogether. Nearly three years after his performance at Van Vechten’s party Robeson wrote Van Vechten to thank him for what he had done for his career. No matter where in the world he was performing, Robeson said, he would always think of Van Vechten because “it was you who made me sing.”

* * *

Van Vechten’s work as a publicist and dealmaker was one of the furnaces that fueled the Harlem Renaissance. His reputation as a white impresario of black art even allowed him to influence the success of African-American performers abroad. When the theater producer Caroline Dudley wanted to export to Paris the sort of black stage entertainment that was all the rage in New York, it was to Van Vechten she turned for advice. He acted as a creative consultant on La Revue Nègre, Dudley’s cabaret show at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées that launched the career of Josephine Baker in 1925. In the grand spectacle that Dudley arranged, Van Vechten’s flamboyant aesthetic sensibilities and his ideas about blackness were vibrantly evident. Twenty-five singers, the Charleston Steppers dancing troupe, and the seven-piece Charleston Jazz Band provided energetic backing to the show’s real stars, who included a nineteen-year-old Josephine Baker. Dudley’s intentions for the show echo Van Vechten’s beliefs in keeping black theater “authentically” black. La Revue Nègre would exhibit the core of blackness, she told a French magazine, “their independence and their savagery, and also that glorious sensual exuberance that certain critics call indecency.” That pronouncement could have fallen straight from Van Vechten’s lips. By neat coincidence, in the same month that La Revue Nègre opened in Paris, Van Vechten published his article “Prescription for the Negro Theatre” in Vanity Fair. The most important thing, he said on how to construct the perfect Negro revue, is to ensure that the chorus girls are nice and dark, and certainly no lighter than “strong coffee before the cream is poured in.” With his dark-skinned cast in place, he then speculated on the type of scenes they should act out, skipping off into the sort of primitivist fantasy that would mark passages of Nigger Heaven, published in 1926, and dictated the look and feel of La Revue Nègre. He daydreamed about “a wild pantomimic drama set in an African forest with the men and women nearly as nude as the law allows.” Against this backdrop he imagined a cast of spear-carrying warriors and “lithe-limbed, brown doxies, meagerly tricked out in multihued feathers” performing a “fantastic, choreographic comedy of passion.”

Despite his successes in raising the profile of black artists at home and abroad, some Harlemites were highly suspicious of his motives. To judge from his early novels, in which black people appear as only mute servants to a cabal of white decadents, Carl Van Vechten seemed the least likely man in New York to act as the downtown envoy to Lenox Avenue. The poet Countee Cullen, for one, did not buy it. From the time of their first meeting in late 1924, Cullen was more than happy to socialize with Van Vechten; he found him unwaveringly good company and even offered to teach him how to Charleston. But he never fully trusted him and suspected Van Vechten was interested in black people for sex and song—and a chance to bolster his own profile. When a Van Vechten article about African-American culture appeared in Vanity Fair, Cullen confided to one of their mutual friends that he had not bothered to read it because he simply thought Carl was “coining money out of niggers.”

That was an unfair judgment. Van Vechten’s interest in black people and their culture was complex, long-standing, and continually deepening, and his work on behalf of Hughes and Robeson brought him no financial gain. The article Cullen referred to was one of a series that Van Vechten published in Vanity Fair in 1925 and 1926 on different aspects of African-American arts. If Cullen really never read these pieces, he missed a landmark in American critical writing. It is not Van Vechten’s prose that makes these essays so remarkable—at times he strays into the melodramatic mode characterizing his earlier writings about black people that tends to fetishize rather than demystify his subject. Rather, it is his approach that is so arresting. In each essay he presented a mainstream white audience with a serious examination of subjects—black theater, spirituals, and the blues—most had never previously encountered and, if they had, would never have considered them art. Yet Van Vechten wrote about them in the same terms he had once written about the opera and ballet. On describing the blues singer Clara Smith, he wrote that her “voice, choking with moaning quarter tones, clutched the heart. Her expressive and economic gestures are full of meaning. What an artist!” He stressed how the inherent racial gifts of black people for improvising and harmonizing had allowed them to create a folk culture whose quality and beauty could not be matched by any the world over. “The music of the Blues,” he wrote, “has a peculiar language of its own, wreathed in melancholy ornament. It wails, this music, and limps languidly: the rhythm is angular, like the sporadic skidding of an automobile on a wet asphalt pavement”; the poetry that accompanies this music is “eloquent with rich idioms, metaphoric phrases, and striking word combinations.” Nobody, certainly no white man, had written about black folk culture quite like this before: not just as worthy and beguiling but as genuine, authentic American art of the highest quality.

However, some Harlemites saw in Van Vechten’s mania for blackness a ghostly shadow of the blackface tradition, a white man who thought African-American culture was a costume that could be slipped on and off for the entertainment of white audiences who sat gawping, astonished that a white man could perform the trick of imitation so thoroughly that he seemed to be inhabiting a Negro soul. Certain black observers publicly expressed their hostility to Van Vechten’s cheerleading for Harlem’s artists. In 1927, at the premiere of Africana, a Broadway revue starring his close friend Ethel Waters, Van Vechten’s exhibitionist display of whooping and cheering and shouting out requests between songs became a feature of the ensuing reviews. “Mr. Van Vechten did everything to prove that Miss Waters is his favorite colored girl and no fooling,” wrote the reviewer for the New York Amsterdam News, clearly of the belief that there was something sinister about Van Vechten’s motivations. “There was the passion of possession in Mr. Van Vechten’s claps and cheers.”

In a way the reviewer had it just right. Van Vechten adored Waters and wanted to flaunt their connection publicly. He even splashed out on a bust of her by Antonio Salemme, the African-American artist, just as he bought a bust of Paul Robeson by the British sculptor Jacob Epstein. After all these years he was as mesmerized by fame as ever and desperate to warm himself in its glow. At times the strength of his desire to connect himself to his favorite stars made him appear desperate, like a celebrity hanger-on forever pushing his way into the back of paparazzi photographs. He once wrote James Weldon Johnson praising his friend as one of the greatest writers in the history of the English language—a peer of Daniel Defoe’s, no less—and said it was an honor for him to be able to call such a man a personal friend. The only thing that irritated him, Van Vechten said, was that he could claim no part in having discovered Johnson for the world to enjoy. Van Vechten, intending this to be the highest compliment, was unaware that it risked making him sound patronizing, possessive, or self-obsessed. To black observers like Countee Cullen this behavior may have appeared unsettling, as if Van Vechten were attempting to own black performers in some way. Yet the crucial point is that Van Vechten behaved in a proprietorial, self-publicizing fashion with all the artists he supported; race had nothing to do with it.

If some blacks were irritated or angered by his self-appointed role as Harlem’s one-man publicity machine, many whites found it absurd and teased him for it. According to a report in Zit’s Weekly, a leading theatrical trade paper, he was reported to have been a victim of a hoax along these lines during a visit to Hollywood in 1928. Egged on by the movie director Dudley Murphy, apparently the actress Madeline Hurlock introduced herself to Van Vechten as Pansy Clemens—note the pseudonym: a gibe at Van Vechten’s sexuality—a light-skinned black woman who wanted to make it big on Broadway. The story runs that Van Vechten fixed her with his usual stare and promised her all sorts of introductions to big-shot producers. When the ruse was revealed a little while later, Van Vechten supposedly hid his embarrassment and insisted that the joke was on Hurlock: he, “an expert on things Ethiopian,” as the reporter described him, could tell that Hurlock really was of Negro heritage, even if she claimed otherwise. Enraged, Hurlock threatened to sue Van Vechten should he try to spread the rumor that she had even a drop of African blood. The story has the strong odor of gossip column embellishment about it, but even if apocryphal, it reflects how his association with black New York society had come to define his public image.

Van Vechten took no mind of the teasing. As he saw it, he was doing vital work, creating a bridge between the racially divided worlds of New York. With pride and seriousness he assumed the role of expert on the New Negro, the man to call upon to explain the mysteries of blackness to curious, or ignorant, whites. By 1927 his favorite party trick was sitting in the dining room of the Ritz, or some other fashionable downtown spot, and pointing out to incredulous friends the patrons who were passing as white. With the Chicago Defender he shared his eccentric pet theory that within a few decades passing would be obsolete; miscegenation would simply absorb all Negroes into the white population. At the end of the decade Andy Razaf, the composer of 1920s’ hits such as “Ain’t Misbehavin,’” dropped Van Vechten’s name into his song “Go Harlem.” “Like Van Vechten, start inspectin,’” ran the line, a clear sign of how closely he had been linked to the neighborhood in the public’s mind by that point.

Van Vechten’s presence in Harlem as a white patron and publicist for black artists was conspicuous—he was temperamentally incapable of being anything else—but it was not unique. The very institutions that provided the organizational thrust of black America’s reinvention, the NAACP and the National Urban League, had been founded by white philanthropists. In March 1925 the white-owned Survey Graphic produced what is still regarded as the Harlem Renaissance bible, entitled “Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro” and soon after published as The New Negro anthology. The Spingarn Medal, given annually by the NAACP to the person who had done most to promote the cause of African-Americans that year, was the gift of the white Spingarn family and the most sought-after prize in Harlem. Without the patronage of these whites—the “Negrotarians,” as the writer Zora Neale Hurston referred to them—the Harlem Renaissance could not have happened.

Inevitably, though, the patronage of whites was wrought with complications. Charlotte Mason was a fabulously wealthy woman with a mansion on Fifth Avenue overflowing with African art, who created around her a circle of black writers dependent on her spectacular but sinister largess. Mason made three basic demands of her stable of black protégés: they call her Godmother, they keep her identity a secret, and they gain her approval for all their writing projects, thus ensuring they stayed true to her idea of their core racial identity. Langston Hughes was one of the godchildren for several years, though it was another of Van Vechten’s close friends, Zora Neale Hurston, who was Mason’s favorite. Hurston believed as fervently as Mason in the ideal of the unpolluted, primitive African soul. Van Vechten believed in that too, of course, but he was no Charlotte Mason, who patronized, hectored, and manipulated the black writers in her orbit to the most outrageous degree. Under the terms of their agreement, Mason paid Hurston two hundred dollars per month and obliged her to collect a great store of material about black folklore, none of which Hurston could use without Mason’s explicit permission. Hurston appeared to have no problem with this. Indeed she thought a cosmic link bound her and Mason together and wrote her letters that express the uncomfortable inequality that defined their relationship. “I have taken form from the breath of your mouth,” reads one. “From the vapor of your soul am I made to be.” In another she described Mason as “the guard-mother who sits in the twelfth heaven and shapes the destiny of the primitives” and signed off, “Your Pickaninny, Zora.”

She never sent letters like that to Van Vechten, who over the years helped many struggling black writers and artists get work and publicity and occasionally gifted them money too. Over two decades Hurston and Van Vechten maintained a friendship of intense warmth, as evinced by their lengthy correspondence, interrupted by silences only when Hurston disappeared on some adventure, through letters that could be flirty and boastful simultaneously but always funny and always passionate, as they swapped stories about Mae West, Lead Belly, or some surprising new discovery—a gospel choir, perhaps, or the Caribbean islands. Van Vechten adored Hurston for the same reason he adored anyone, black or white: he thought she was an extraordinary individual, a beautiful, charismatic talent whose entire being resonated with a life-affirming energy. Ultimately that may have been the crucial distinction between him and Godmother Mason. Both believed in the singularity of the black soul, but Van Vechten wanted to be a friend and peer of the black people who interested him rather than some omnipotent overlord always sitting in stern judgment.

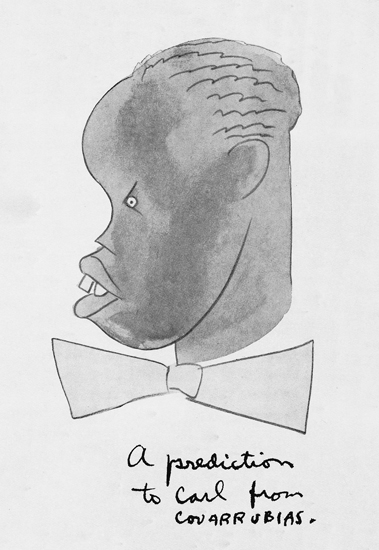

A caricature of Carl Van Vechten as a black man by Miguel Covarrubias, entitled A Prediction

That positive distinction had a crucial effect on his relationships with Harlemites. Behind his back there were some teasing words and eyes lifted to heaven when he tried too hard to appear at home in the company of black people or display his knowledge of their culture, but it was that very same attitude of unself-conscious enthusiasm that endeared him to many. He thought the differences between blacks and whites were self-evident but no reason to keep the races apart. They were in fact an exhilarating life force, what the historian Emily Bernard has aptly termed his belief in “the importance—and insignificance—of racial difference.” Harold Jackman, a black teacher and writer who was a linchpin of Harlem society, circled Van Vechten with gawping curiosity when the two first met in February 1925. Jackman said he had never before felt comfortable in the company of white people, but in Van Vechten’s presence racial differences seemed to dissolve. “You are just like a colored man!” he exclaimed. “I don’t know if you will consider this a compliment or not.” To Van Vechten, who prided himself on his ability to effortlessly befriend exceptional people in almost any environment, it would have surely been the highest compliment possible. However, considering Van Vechten thought he had been able to pass as black in Chicago two decades earlier, Jackman’s praise would not have come as a surprise to him. When the artist Miguel Covarrubias drew a caricature of Van Vechten as a black man entitled A Prediction in 1926, Van Vechten had special copies printed to keep for posterity and send to friends. Being black, he was beginning to believe, was just another of his exquisite talents.