On May 8, 1945, Churchill declared victory over Germany to a throng of revelers from a balcony overlooking Whitehall. That same day, resistance forces deep in the heart of Telemark went into action. After years of fighting as an underground army, they took back Rjukan and the surrounding towns in open daylight. They occupied Vemork and other power stations in the area, seized control of communication lines and key public buildings, and took responsibility for law and order, including the arrest of Norwegian traitors and SS officers. The soldiers in the German garrisons surrendered their weapons and went where they were told. Similar scenes played out across the rest of Norway. The invaders numbered almost 400,000 in total, Milorg forces roughly 40,000. There could have been an ugly last-ditch fight, but there was none. Norway was free, and parties started in the streets of Oslo and throughout the country.

A month after the German surrender, King Haakon VII stepped onto Norwegian soil at the pier in front of Oslo’s town hall. Despite the steady drizzle, 50,000 Norwegians cheered and waved flags to celebrate his return. Among those present to honor him were Colonel Wilson and over one hundred members of Kompani Linge, most of them wearing helmets or badges that named their operations. Grouse and Gunnerside were well represented.

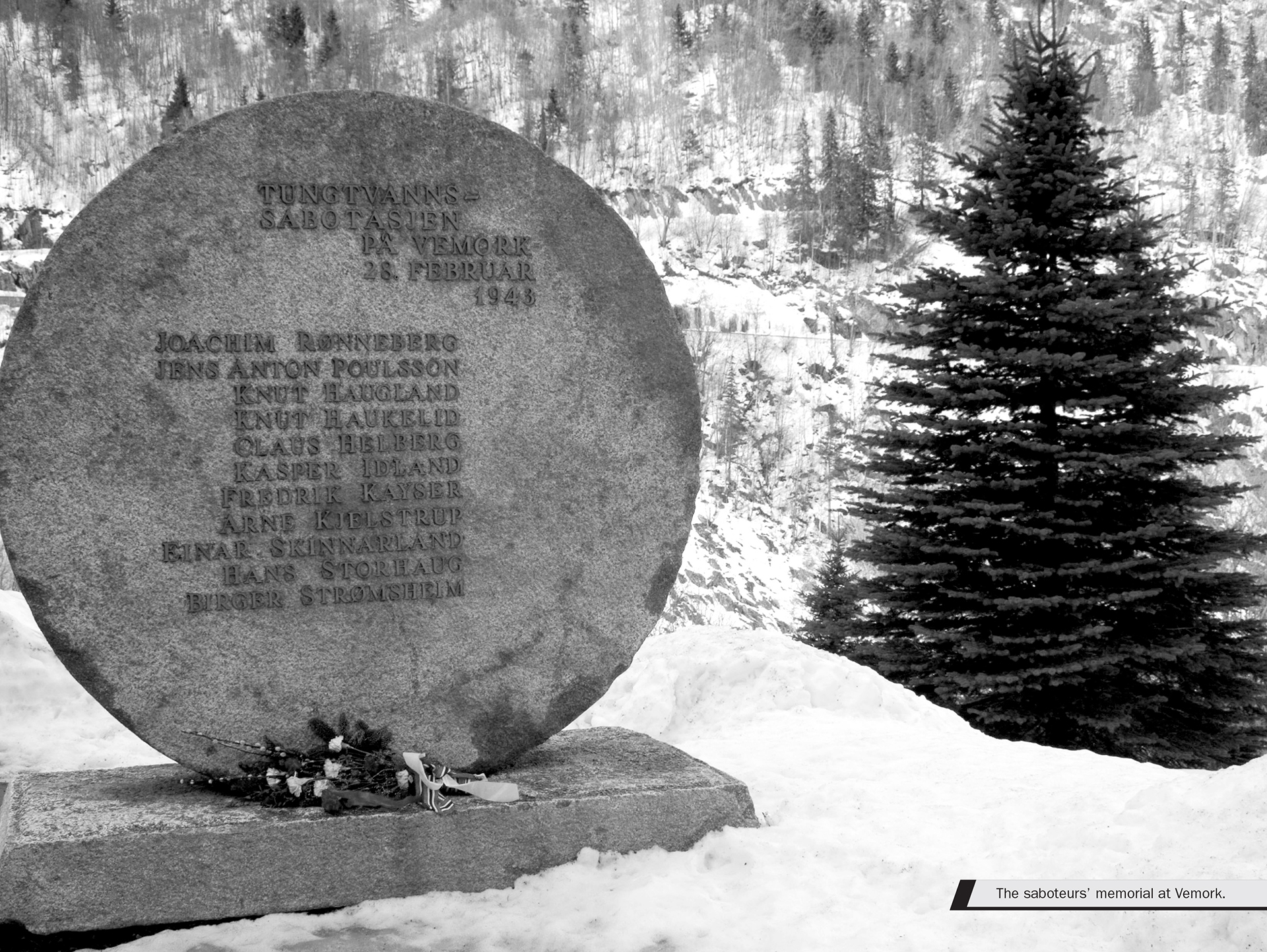

As time went on, those who had participated in the heavy-water sabotage were pinned with medals from many grateful nations: Norway, Great Britain, Denmark, France, and the United States. Nor was the sacrifice of the British Royal Engineers and RAF crews of the ill-fated Operation Freshman forgotten. Thirty-seven bodies were recovered and buried at grave sites in Norway. The Norwegians also erected memorials for the innocent lives lost in the American bombing raid at Vemork and in the Hydro sinking.

Beyond the medals and the memorials, the war marked the men of Grouse and Gunnerside in other ways, sometimes dark ones. They had all spent the rest of the war involved in various commando activities. Joachim Rønneberg destroyed German supply lines in the Romsdal Valley, including a key railway bridge. Kasper Idland operated submersible canoes in limpet-mine attacks against enemy ships in Norwegian harbors. Hans Storhaug and Fredrik Kayser suffered great hardship while establishing resistance cells. Knut Haugland continued to set up wireless radio links with London to coordinate Milorg activities.

They had seen friends die. Some had killed. All of them had lived under the constant threat of discovery and death. At times, they woke up in the middle of the night, imagining the enemy at the door, reaching for guns that were not there. Einar Skinnarland’s children knew not to approach their father suddenly.

In the years after the war, a few of the saboteurs turned to alcohol to dull memories they never asked for. Many sought solace in the Vidda, the very place they had once struggled to survive. The sense of the “smallness of being a human being in nature” was relief for Rønneberg. “You could sit down on a stone and let your thoughts fly away.” Knut Haugland lived for 101 days in 1947 as the radio operator on the Kon-Tiki, a simple raft that crossed the Pacific Ocean with only a six-man crew. Beyond offering a great adventure, the journey helped him to heal. Only in his last years did Skinnarland revisit his war diary and the long string of telegrams he had sent from the Vidda, and only then did he allow himself some pride over what he had endured for the sake of his country — and the world. What nature and time could not mend, friendship supported them through. Until the end of their lives, the members of Kompani Linge gathered often to share experiences that few others could understand.

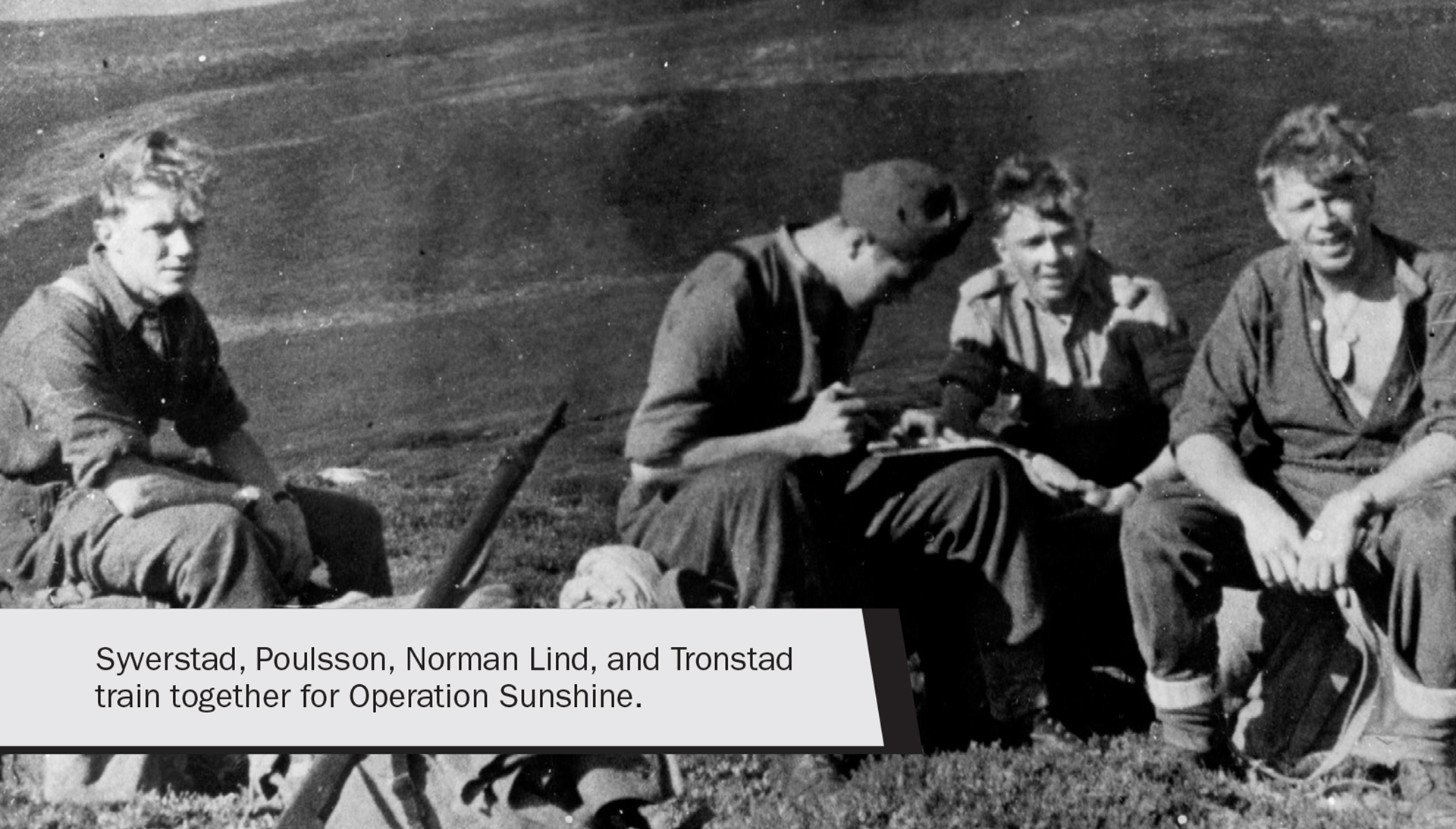

Sadly, Tronstad died before he could see his country free. He returned to Norway in October 1944 to oversee “Operation Sunshine,” coordinating the work of 2,200 resistance fighters in Telemark and protecting “the major industrial objectives” in the area, including its power stations. Many former Kompani Linge members participated in Sunshine, including Poulsson, Helberg, Kjelstrup, and Syverstad, who had come to London for training after the ferry sabotage. Einar Skinnarland served as Tronstad’s radio operator. Over the next five months, they orchestrated steady drops of arms and supplies, recruited and trained resistance cells in firearms and explosives, and performed small-scale sabotages of arm dumps. Tronstad ate, slept, hunted, and skied side by side with his men. Most had thought highly of him while he was their boss in London. In the wilds of Telemark, their loyalty and respect deepened into something greater still.

By spring 1945, the time for an uprising against the Germans looked imminent. On the night of March 11, Tronstad was interrogating a Nazi sympathizer when suddenly the door to his hut burst open. The sympathizer’s brother entered with a gun and started shooting. Tronstad was killed in the ambush. Jens-Anton Poulsson took over as the leader of Operation Sunshine.

Afterward, Tronstad’s wife, Bassa, received a letter Tronstad had written her in case of his death. “Dearest Bassa,” he wrote. “I have the honor to lead an important expedition home, which will be of great importance to Norway’s future. It is in line with the course I chose on April 9, 1940, to put all my effort and abilities toward our country’s welfare…. The war is singing its last verse, and it requires every effort from all who would call themselves men. You will understand that, won’t you? We have had so many magical happy years, and my highest wish is to continue that happy life together. But should the Almighty have another course for me, know that my last thought was of you…. Time is short, but if all will not go well, don’t feel sorry for me. I am completely happy and thankful for what I have had in life even though I very much would like to live to help Norway back to its feet.” He wished the best for Sidsel and Leif and concluded that he looked forward to meeting her again. The letter was signed “Your beloved.”

When Tronstad sent Gunnerside off on its mission, he spoke of their action being remembered for a hundred years. But he fought and died for a different reason than fame and renown — a different “why” — and he made that “why” plain in his letters home: for Norway, for its land, and its people.

Fredrik Kayser ruminated on the same question: “Why?” In speeches, he called on a letter written by a nineteen-year-old Norwegian to his parents and sisters before he left to fight the Germans. “I love you all, but my country first, then you … A poet once said that ‘if a people are to live, someone must die’ … If I do not come back, it’s because someone must die.”

Rønneberg, the last surviving saboteur, who was ninety-five years old in 2015, spoke eloquently about why he braved the North Sea to be trained in Britain and why he then returned, by parachute, to Norway. “You have to fight for your freedom,” he said. “And for peace. You have to fight for it every day, to keep it. It’s like a glass boat; it’s easy to break. It’s easy to lose.”